Eigg

| Scottish Gaelic name | Eige |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ˈekʲə] ⓘ |

| Old Norse name | Unknown |

| Meaning of name | Scottish Gaelic for 'notched island' (eag) |

An Sgùrr | |

| Location | |

| OS grid reference | NM476868 |

| Coordinates | 56°54′N 6°09′W / 56.9°N 6.15°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Small Isles |

| Area | 3,049 ha (11.8 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 28 [1] |

| Highest elevation | An Sgùrr, 393 m (1,289 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Council area | Highland |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 105[2] |

| Population rank | 47 [1] |

| Population density | 2.7 people/km2[3] |

| Largest settlement | Cleadale |

| References | [3][4] |

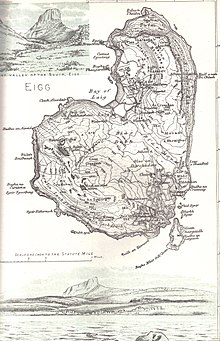

Eigg (/ɛɡ/ eg; Scottish Gaelic: Eige) is one of the Small Isles in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the island of Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is nine kilometres (5+1⁄2 miles) long from north to south, and five kilometres (three miles) east to west. With an area of just over 3,000 ha (11.6 sq mi) it is the second-largest of the Small Isles after Rùm. The highest eminence on Eigg is The Sgùrr, which is formed from the Sgurr of Eigg Pitchstone Formation, which erupted into a valley of older lavas during the Eocene epoch.

There are numerous archaological sites dating from the prehistoric period of human occupation with the earliest written references relating to the Irish monk Donnán who arrived on Eigg around 600 AD. Commencing in the early 9th century, Norse settlers established the Kingdom of the Isles throughout the Hebrides. The 1266 Treaty of Perth transferred the territories of the Kingdom of the Isles to King Alexander III of Scotland. From the late 14th century, the island became a possession of Clanranald, during which time a notorious massacre took place during a period of clan warfare. After more than four centuries in Clanranald's hands, the island was sold during the 19th century, and the new laird evicted many of his tenants en masse and replaced them with herds of sheep.

There were then a series of owners until the island was purchased by the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust in 1997. The trust is a form of community ownership and another stakeholder, the Scottish Wildlife Trust, manages the island as a nature reserve.[5] Eigg now generates virtually all of its electricity using renewable energy.[6][7] In April 2019, National Geographic discussed the island in an online article, estimating the average number of annual visitors at 10,000.[8]

Geology

[edit]

The larger part of the island is formed from olivine-phyric basalt flows erupted during the Palaeocene epoch. Together with flows of hawaiite and mugearite, these form the Eigg Lava Formation. The Sgùrr is formed from the Sgurr of Eigg Pitchstone Formation, a porphyritic rhyolitic pitchstone that erupted into a valley eroded into the older lavas during the Eocene epoch. It displays columnar jointing formed as the lava cooled.[9]

In the north of the island are a series of sedimentary rocks of Middle Jurassic and Upper Cretaceous age. The oldest of these, and hence lowest from a stratigraphic perspective is the fossiliferous Bearreraig Sandstone which is calcareous in nature. It is overlain by the Lealt Shale which consists of a lower and an upper grey shale (respectively the Kildonnan and Lonfearn members) separated by a thin band of algal limestone. The shale is overlain by the thicker Valtos Sandstone which contains concretions. It is found along the east coast northwards from Poll nam Parlan and around the northern end and down the eastern side of the Bay of Laig. This in turn is overlain by the bivalve-rich limestone and shale of the Duntulm Formation and lastly the dark shales and ostracod-bearing limestones of the Kilmaluag Formation. A fossilised limb bone, considered most likely to be from a Middle Jurassic stegosaurian dinosaur, was discovered at a coastal exposed Valtos Sandstone Formation in 2020; it is the first confirmed dinosaur fossil to be found in Scotland away from the Isle of Skye.[10][11] The Turonian (Upper Cretaceous) age Strathaird Limestone Formation is the youngest part of the Mesozoic sequence preserved beneath the unconformity at the base of the Eigg lavas and its found in a strip along the coast just west of the bay of Laig.[12]

Both the igneous and the sedimentary rocks are cut through by a swarm of Palaeocene age dykes generally aligned NW-SE. A handful of faults are mapped on the same alignment, the two most significant ones stretching SE from Bay of Laig. A band of microsyenite stretches around the hillside southeast of the Sgùrr. Isolated pockets of peat of postglacial origin are to be found behind Bay of Laig whilst to its north are areas of hummocky moraine. Landslips occupy the whole coastal strip in the northeast of the island and the embayment behind Bay of Laig and effectively mask much of the outcrop of the Mesozoic sediments.[12]

Geography

[edit]

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | An Laimhrig | |

| Pronunciation: | [əˈlˠ̪ajvɾʲɪkʲ] ⓘ | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Clèadail | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʰliət̪al] ⓘ | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Eige | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈekʲə] ⓘ | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Uamh Fhraing | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈuəv ˈɾaŋʲkʲ] ⓘ | |

Eigg measures nine by five kilometres (5+1⁄2 by 3 miles) and is 21 kilometres (11+1⁄2 nautical miles) by sea from the nearest port of Mallaig. The centre of the island is a moorland plateau, rising to 393 m (1,289 ft) at An Sgùrr, a dramatic stump of pitchstone which is the "most memorable landmark in the Hebridean seas".[14] Walkers who reach the top can, in good weather, take in views of Mull, Coll, Muck, the Outer Hebrides, Rùm, Skye, and the mountains of Lochaber on the mainland.

The plateau in the northern part of the island, at Beinn Buidhe, drops to a fertile coastal plain on its western side, containing Cleadale, the main settlement on Eigg. At the southern end of the plain, in the centre of the island, lies the bay of Laig, known for its quartz beach, called the "singing sands" on account of the squeaking noise it makes if walked on when dry.[15] The first written description of this effect was penned by Hugh Miller in the 19th century:

I struck it obliquely with my foot, where the surface lay dry... [which] elicited a shrill sonorous note... I walked over it, striking it obliquely with each step and with every blow the shrill note was repeated.[15]

The plateau is cleaved by a central valley, stretching from the vicinity of Laig, in the north, to Galmisdale at its southeastern end, which forms the main port. Beyond the southeast coast lies the small islet of Eilean Chathastail.[4]

Etymology

[edit]

Adomnán calls the island Egea insula in his Vita Columbae (c. 700 AD).[16] Other historical names have been Ega,[17] and Ego.[18] The Gaelic Eige means "notch" probably with reference to "the marked depresssion that runs across the middle of the island".[19] A 2013 study also suggested a possible Norse origin.[18][note 1]

Eigg was also known as Eilean nam Ban Móra - "the island of the great women".[21] (Local tradition claims that the dun at Loch nam Ban Mora (see below) was once inhabited by unusually large women.[22]) Martin Martin reported in 1703 that "the natives dare not call this isle by its ordinary name of Egg when they are at sea, but island Nim-Ban-More."[23]

Some of the island settlement names are of Norse origin. Cleadale (Clèadail) may mean "valley of the ridged slope". The first element of Galmisdale is possibly a personal name. Laig may derive from "muddy bay".[24] Grulin is of Gaelic origin, Scottish Gaelic: Grùlainn meaning "stony land".[25]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

At Rubh' An Tangaird, near Glamisdale on the southern coast, there are the remains of an oval house, with thick walls, and an upright stone at each side of the doorway. There are comparable structures in Shetland such as at Scord of Brouster, which suggests a neolithic date.[26]

Evidence for the island having been occupied in the Bronze Age includes two axes and a cache of flints, one of them being thumbnail scraper found near Galmisdale, together with significant metalworking debris.[27][28] A barbed-and-tanged flint arrowhead of uncertain date was found to the south of Kildonnan.[29]

Iron Age

[edit]

Early Iron Age hut circles are found throughout the island. One located near the northeast coast near Sron na h-Iolaire is close to a cave to which walls have been artificially added; several hammerstones are located in the cave and surrounding vicinity, some with concretions of crushed shells stuck to them. The cave site is difficult to reach leading archaeologists to speculate that the site may have been used for hermitic purposes.[30]

Later in the Iron Age, the inhabitants of Eigg chose to fortify the island. Small fortifications restrict access to rocky knolls at Garbh Bealach west of Galmisdale[31] and Poll Duchaill on the northwest coast[32] and on the promontory of Rudha na Crannaig south of Kildonnan.[33] More substantial duns existed at Galmisdale Point,[34] and at Loch nam Ban Mora, the latter of which is located on an island.[22]

Early Christianity

[edit]The Irish missionary activity which caused Columba to found a monastery on Iona also brought the Irish monk Donnán to Eigg around 600 AD, where he established a monastery, at Kildonnan.[35] Columba had warned him of the dangers of settling in Pictish territory[36] and Donnan was murdered on Eigg along with 52 of his monks in 617.[37]

By the following century, the monastery was significant enough for the death of its superior, Oan, to be mentioned in the Annals of Ulster. The monastery, which was excavated in 2012, was located within an oval enclosure, surrounded by a ditch, housing a rectangular chapel in the centre, and with a handful of smaller buildings either side.[38][39] A handful of early inscribed stone slabs were located there, of which one bears a Pictish design, comprising a hunting scene,[note 2] with a cross on its obverse.[40]

On the coast at the opposite side of the island, are 16 or more quare cairns, lined up neatly into groups; they are each between 3.5 and 5 metres (11 and 16 ft) square, most being bordered by a stone kerb, and some having upright cornerstones. This form of cairn is usually associated with the Pictish kingdoms of the first millennium AD. The site may thus have some connection with the contemporary monastery at Kildonnan.[41]

Kingdom of the Isles

[edit]

Commencing in the early 9th century Norse settlers established the Kingdom of the Isles throughout the Hebrides. A silver/bronze sword handle from the beginning of this period was found in 1830, buried in a field named Dail Sithean near Kildonnan, together with an iron axehead, leather belt, buckle, wollen cloth, and a whetstone.[42] Wetlands near Laig, (which became peat-bog, during later centuries) appear to have been used for storing partly finished boat parts, as was common in Viking Scandinavia. A few oak posts, 6 feet (1.8 m) in length, for the stern of a longship were found there.[43] A simple bronze brooch was found at a nearby site.[44]

By the late 11th century the Isles were controlled by the Crovan dynasty but the dictatorial style of Guðrøðr Óláfsson (aka Godred the Black) appears to have made him very unpopular with the Islesmen, and the ensuing conflicts were the beginning of the end for Mann and the Isles as a coherent territory under the rule of a single magnate. The powerful barons of the isles began plotting with an emerging and forceful figure – Somerled, Lord of Argyll. Godred engaged Somerled's forces in the naval Battle of Epiphany in 1156. There was no clear victor, but it was subsequently agreed that Godred would remain the ruler of Man, the northern Inner Hebrides and the Outer Hebrides, whilst Somerled's young sons would nominally control the southern Inner Hebrides, Kintyre and the islands of the Clyde under their father's supervision.[45][46]

By the mid 13th century the Small Isles were in Lordship of Garmoran, a possession of Clan MacRory founded by Somerled's grandson Ruaidhrí mac Raghnaill.[47] At this point the islands was nominally subject to Norway but in 1266, the Treaty of Perth transferred the territories of the Kingdom of the Isles to Alexander III of Scotland[48] and Dubhghall mac Ruaidhrí, Lord of Garmoran, found that he had a new overlord. He, and others who had supported the Norse, had the opportunity to emigrate under the terms of the treaty[49] and Dubhghall died in 1268, possibly in exile.

By 1337 the sole MacRory heir was Amy of Garmoran, who in that year married John of Islay, Lord of the Isles,[3] leader of the MacDonalds, the most powerful group among Somerled's heirs. Circa 1350 they divorced and John deprived his eldest son, Ranald, of the ability to inherit the MacDonald lands. As compensation, John granted Lordship of the Uists to Ranald's younger brother Godfrey, and made Ranald Lord of the remainder of Garmoran, including Eigg.[50][51][note 3]

Early Clanranald rule

[edit]

Upon the death of John of Islay his son Donald, Ranald's half-brother, was named Lord of the Isles at Kildonan on Eigg in 1387. Ranald, who became the founder of Clan Macdonald of Clanranald, appeared content with this decision by his father as suggested in the Charter of 1373, the misgivings of many of the noblemen of the Isles notwithstanding.[53][54][note 4]

However, when Ranald died in 1386 at Castle Tioram,[56] Godfrey seized his lands, leading to violent disputes between his heirs (the Siol Gorrie) and those of Ranald (Clanranald). In 1427 James I arrested the leaders and declared the Lordship of Garmoran forfeit.[57]

Ranald Bane MacAllan, leader of Clanranald, refused to support the rebellion of Donald Dubh against James IV. In 1505, after the rebellion was defeated, he was "now in high favour at Court".[58] In 1520, Ranald Bane's son Dougall, the 6th chief of Clanranald, was assassinated by his own clansmen in part for his lack of opposition to the crown. Leadership of Clanranald then passed not to his sons but to the Moidart branch of the clan. In 1534 John Moidartach, 8th of Clanranald, managed to obtain from the king a charter confirming his position as laird of Eigg and Morar.[59]

Writing in 1549, Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles wrote of "Egge" that it was: "gude mayne land with ane paroch kirk in it, with mony solenne geis; very gude for store, namelie for scheip, with ane heavin for heiland Galayis".[60][note 5]

Massacre cave

[edit]

Uamh Fhraing, also known as the Cave of Francis[note 6] or the Ribbed Cave, lies on a raised beach on the south coast of Eigg. The entrance is low and narrow but the interior is about 60 metres (200 ft) long and 6 metres (20 ft) wide.[62] In 1577,[63] according to Clan MacLeod historians, a MacLeod galley was forced ashore by bad weather at Eilean Chathasteil. Led by a foster-son of Alasdair Crotach the 30 men roasted some cattle and "molested" the young girls who were tending them. The local men then arrived on the islet and massacred most of the MacLeods, sparing only a few leaders whose legs and arms were broken and who were then cast adrift in the Minch.[64] They were however either rescued by MacLeods from elsewhere or perhaps drifted back to Dunvegan.[65][64] In the MacDonald version of the story the girls were raped and the Macleods were asked to leave. Looking for revenge, a large group of MacLeods led by Alasdair Crotach landed on Eigg, but had been spotted by the islanders, all but one of whom decided to hide in the cave.[65]

The traditions go on to say that the MacLeods conducted a thorough but fruitless search for the inhabitants. They found only an old lady at the singing sands who they spared and left the island after 3 days. Just as they were leaving they saw a scout outside the cave and were able to follow their footprints in the snow to the entrance. The MacLeods piled thatch and heather at the cave entrance, and set fire to it. Water from a waterfall nearby dampened the flames, so that the cave was filled with smoke, asphyxiating the 395 people inside.[65][66] Human remains inside the cave have been reported many times over the centuries.[note 7] Most of the remains were removed from the cave and reburied by 1854[67][68] although occasionally further sets of human bones are exposed.[note 8]

However, serious doubts remain about the veracity of the tale. MacPherson wrote of it that "it is curious to find how difficult it is to determine its date or to decide with certainty on whom the odium of this deed should lie."[61][note 9] The difficulties include that both Alasdair Crotach and his son Uilleam died long before 1577 and that similar stories are related about both Coll and Ardnamurchan. Furthermore, Privy Council papers from 1588 describe massacres on all the Small Isles perpetuated by Lachlan MacLean of Duart and 100 Spanish soldiers from the crew of an Armada vessel that sank off Tobermory.[72][67][note 10] The idea that two such massacres occurred on Eigg within eleven years has thus been questioned.[70][75][note 11]

Jacobite risings

[edit]Clan Ranald took part in the Jacobite rising of 1689 against William II.[76] The following year a boat had gone from Eigg to Armadale on Skye and found that the Royal Navy ship the Dartmouth was anchored there. A brawl broke out and one of the Cameronian soldiers was killed. The captain ordered the Dartmouth to Eigg and pillaged the island. The soldiers also took an island girl on board and returned her the next day with her hair shorn.[77][note 12]

The men of Eigg also rose and fought in both the Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745. After the failure of the rebellion a navy vessel arrived on the island seeking one of the Clanranald officers, John MacDonald of Kinlochmoidart. After his discovery on the island all 38 surviving islanders who had served in the '45 were arrested by Captain John Ferguson.[80][81] They were held on board H.M.S. Furnace[80] and remained there when it became a prison hulk anchored in the River Thames off Gravesend, Kent. Although many died aboard the Furnace from torture, disease, or starvation, the remaining 16 were eventually transported to the Colony of Barbados and the Colony of Jamaica, to work as slave laborers on sugar cane plantations.[82][83][note 13]

19th century clearances

[edit]

The 18th century introduction of the potato to Eigg lead to increased yields compared to cereal growing[86] and by the end of the century the population had expanded to about 500[87] The outbreak of the Peninsular War created a potential new route to wealth, by limiting foreign supplies of valuable minerals. Kelp could be harvested to produce soda ash and rapidly increased in price.[88] In 1817, the estate factors reduced the size of each tenancy (for example, Cleadale was re-arranged into 28 plots), to stop their tenants from becoming self-sufficient and forcing them to also harvest kelp in order to break even. However, soon after the creation of these smaller tenancies (crofts), foreign mineral supplies were re-introduced, as the Napoleonic Wars had ended. The kelp price crashed and the crofters struggled to avoid destitution.

Some families voluntarily emigrated to Antigonish County, Nova Scotia to escape both rising rents and crushing poverty. They settled on a high plateau near the coast of the Northumberland Strait, which they named Eigg Mountain.[89] Meanwhile, like many other Anglo-Scottish landlords during the Highland Clearances, Ranald George Macdonald, 19th Chief of Clanranald issued orders to evict the whole village of Cleadale, and use the land for sheep; both to cover his debts and to continue funding his extremely extravagant spending.

Raonuill Dubh's son Aonghas Lathair MacDhòmhnaill took over the tack of Eigg and gained local infamy by beginning evictions from Cleadale. When severe hardships fell upon Aonghas Lathair and his family, which resulted in the tacksman dying by suicide, the old people of Eigg blamed the family's misfortune on the curse that was said to have been put on them by the women whom he had evicted from Cleadale.[90] In 1827 Macdonald found someone willing to purchase Eigg, and cancelled further evictions. After 440 years Clan Ranald rule of Eigg had come to an end.[91]

Later lairds

[edit]

The purchaser and new owner of Eigg was Dr. Hugh MacPherson, a Sub-Principal at King's College, Aberdeen. He was not wealthy and had 12 children but was well-connected.[91] The Scottish geologist and writer Hugh Miller visited the island in the 1840s and wrote a long and detailed account of his explorations in his book The Cruise of the Betsey published in 1858. Miller was a self-taught geologist and the book contains detailed observations of the geology of the island, including An Sgùrr and the singing sands.

The financial woes of the islanders were compounded by the Highland Potato Famine. Furthermore, Dr. MacPherson decided to evict his tenants en masse and replace them with herds of sheep.[92] In 1853, the whole village of Gruilin was cleared and all but three families emigrated to Nova Scotia.[92] One woman who was left behind never recovered from the evictions and threw herself into the sea off the cliffs.[92] Three more villages were similarly cleared shortly thereafter.[93]

The MacPhersons sold Eigg to Robert Thompson, a wealthy shipbuilder, in 1893. He died in 1913 and is buried on Eilean Chathastail.[37] After being sold by Thompson's family in 1917, the island passed through various hands, including the cabinet minister, Walter Runciman, until being purchased by Keith Schellenberg in 1975.[37] Unlike his predecessors, who had sought to use the resources of the island for their own power, profit, or leisure, Schellenberg had conservationist motives; he wished to restore its listed buildings, and preserve the natural environment.[94]

Gaelic literature and music

[edit]

One of the men from Eigg who joined the Clanranald forces in the Jacobite rising of 1715 was Iain Dubh Mac Iain 'ic Ailein, the tacksman at Grulin. He was a well-known poet whose works include Trod nam Ban Eiggach that satirises the sharp-tongued women of the island and Bruadar mo Chor na Rioghachd ("A Dream about the State of the Nation"). The latter is a pro-Jacobite Aisling, or dream vision poem, in which he hopes to see Queen Anne ripped apart by deerhounds.[95]

After the death of his father Raonuill Dubh MacDhòmhnuill, the eldest son of Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair, moved from Arisaig to become Clanranald tacksman of Laig. While serving as tacksman Raonuill Dubh collected and published the poetry anthology called The Eigg Collection in Edinburgh in 1776. He is believed to have drawn heavily upon oral poetry collected by his father and also upon a similar poetry collection made by Dr. Hector Maclean of Grulin.[96] The latter manuscript contains an additional 104 pages of material, including fourteen of Tiree-born Canadian Gaelic bard Iain mac Ailein's poems in his own hand, and is now preserved in the Nova Scotia Archives.[97]

Allan MacDonald collected numerous Catholic hymns and works of oral poetry by Donald MacLeod, a seanchaidh from Eigg resident in Oban. MacDonald supplemented these with several of his own compositions and translations and anonymously published a Gaelic hymnal in 1893.[98][99]

Donald MacQuarrie was a resident of Grulin who became a pupil of piper Raghnall Mac Ailein Òig of Morar during the latter's visits to Eigg in the late 17th century. He developed quickly and received further support from the MacCrimmon piping family on Skye, becoming known as am Piobair Mór - "the great piper".[100]

War poet and Seanchaidh Hugh MacKinnon (1894-1972), a veteran of the First World War, composed a Gaelic lament for the fallen soldiers of the island, Ò, tha mi 'n-duigh trom fo lionn-dubh, ("I am today sad and mournful"), which is still read aloud at the Eigg War Memorial every November 11th.[101][102]

Religion

[edit]Catholicism

[edit]

Allan, 9th chief of Clanranald, commenced the rebuilding of the Kildonnan Chapel on the site of Donnan's 7th century monastery in honour of his father, John Moidartach's, vow to build seven new churches on his lands. However it was likely never completed as it was found as an unroofed ruin by Fr. Cornelius Ward in 1625.[40][103]

Ward, a Franciscan friar, had been sent by the Catholic Church in Ireland in order to proselytise the population of Scotland's west coast. His "chatty mission report" indicates that he converted 198 individuals and baptised 16 during his 8-day visit. (The only family not to convert were relatives of the Protestant minister of Sleat, Neil MacKinnon.)[70][103] Infuriated by Ward's success, MacKinnon set off for Eigg in the company of some soldiers with the intention of arresting Ward but the islanders threatened him sufficiently forcefully to secure his withdrawal. The Clanranald bailie later persuaded him to turn a blind eye, in return for the island's tithes.[103][104]

The friar was unable to reconsecrate the Chapel and it came to only be used for burials. One grave had a carved cover popularly re-interpreted as a medieval sheela na gig.[105][106] Martin Martin recorded a ritual in 1703 that suggests that visiting priests were at pains to integrate traditional beliefs into their formal doctrines.[107]

"There is a well, called St. Katherine’s Well; the natives have it in great esteem, and believe it to be a catholicon for diseases. They told me that it had been such ever since it was consecrated by one Father Hugh, a Popish priest, in the following manner: he obliged all the inhabitants to come to this well, and then employed them to bring together a great heap of stones at the head of the spring, by way of penance. This being done, he said mass at the well, and then consecrated it; he gave each of the inhabitants a piece of wax candle, which they lighted, and all of them made the dessil, of going round the well sunways, the priest leading them: and from that time it was accounted unlawful to boil any meat with the water of this well."[23]

To evade the religious persecution the British government imposed upon the Catholic Church in Scotland and which contributed to the Jacobite risings, the laity secretly and illegally attended mass at a mass stone inside a large high-roofed coastal cave, which can only be accessed during low tide, now known as Cathedral Cave. Later, Catholic worship moved into "the lower floor of an old farmhouse" which remained the island's Mass house until 1910.[108][109][110] In that year, St Donan of Eigg Roman Catholic Church was built in Cleadale by the Diocese of Argyll and the Isles and continues to be served by visiting priests from Morar.[111]

Church of Scotland

[edit]The Reformation made slow headway in the Gàidhealtachd of Scotland due to the lack of Gaelic-speaking ministers. Eigg became part of the parish of Sleat in 1624 but there were no converts at that time.[103] The Small Isles became a Church of Scotland parish in their own right in 1740. The first minister was Donald McQueen, who rarely ventured to Eigg as the only significant Protestant populations were on Muck and Rum. Malcolm Macaskill, known as Maighstir Calum, who became the incumbent in 1757 had the benefit of glebe land at Kildonnan to farm and he leased more land at Sandaveg and Sandavore.[112] The glebe was later moved to Sandaveg and was the largest in Scotland at the time. The Skye Presbytery gave up a plan to rebuild the church at Kildonnan in favour of building a two-storey manse for him. This was not completed until 1790 and the first occupant was the new minister, Donald MacLean.[112] MacLean developed a reputation for heavy drinking and was eventually deposed by the General Assembly.[113]

The New Statistical Account of 1831 was penned by Revd. Neil Maclean, who noted that the parish had no road or church, no post or other regular means of communicating with the mainland and only one inn – at Galmisdale on Eigg.[114] John Swanson became minister in 1838 and five years after his arrival he left the kirk and joined the Free Church of Scotland during the Disruption of 1843.[113] Prior to his arrival relationships between the Catholic and Protestant populations of Eigg had been good and marriages between the two were common. However, Swanson’s zealous fight against “Popery” led to increasing sectarianism. Swanson built a new school where lessons were taught in Gaelic, leading to a significant increase in literacy. He also introduced Gaelic bibles to the island, the teachings of which (now being accessible to ordinary citizens) led to growing anti-landlord feelings amongst the oppressed tenants.[115] Having left the established church Swanson also had to leave the manse. All but three of his congregation of 200 followed him into the Free Church but he was denied the landlord’s permission to build himself a house. Instead, he bought a small sailboat – the Betsey, later used by Hugh Miller - and “turned it into a floating manse”.[116]

Community buy-out

[edit]In the early 1990s, a fire at Schellenberg's home on the island destroyed a 1920s Rolls-Royce; Police suspected the fire was due to arson.[94] Some locals claimed that since the late 1980s, he had neglected homes, closed the community hall, and restricted leases.[94] While admitting that he had closed the community hall (but only in the evenings), and had refused to continue one particular lease, he told the press that "drunken hippies and drop-outs" were unfairly branding him a despot.[94] In 1994, now in his 60s, Schellenberg concluded that trying to conserve the island was not worth facing violent intimidation for,[94] and in the following year sold it to Gotthilf Christian Eckhard Österle from Germany who styled himself "Professor Marlin Eckhard-Maruma" or simply "Maruma" and who claimed to an artist;[117] Schellenberg retained ownership of the 18th century Manse.

Nevertheless, by then a community trust had been formed by the Highland Council, the Scottish Wildlife Trust, and a number of residents – particularly those newly moved to the island – with a view to buying Eigg from the laird. In 1997, this Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust persuaded Eckhard to sell, and bought it from him.[118] The ceremony to mark the handover took place a few weeks after the 1997 General Election and was attended by the Scottish Office Minister, Brian Wilson, a long-standing advocate of land reform; he used the occasion to announce the formation of a Community Land Unit within Highlands and Islands Enterprise to support further land buy-outs in the region.

Between then and the 2011 census, the ordinarily resident population expanded from 65 to 83; this increase of 24 percent (six times greater than for the Scottish islands as a whole[note 14])[119] was principally formed by young people who moved to Eigg to set up in business, as well as a handful of former residents returning to the island. However, by 2003, the residents' representatives on the trust's board were entirely people who had moved to the island since the trust took over.[120]

A few longstanding residents complained that the trust focused on the new residents, while ignoring the concerns of the families who had lived on the island for generations; for example, they complained that new mains power connections, and housing provision, was given to the families of trust members, not indigenous islanders.[120] One islander from an old Eigg family declared that the trust "is not a democracy ... it is the mafia".[120] More recently, more positive articles have been published, showing a different picture of the island.[121]

Eigg was featured on the American television program 60 Minutes in November 2017[122] and an extended feature on its companion web site 60 Minutes Overtime in July 2018.[123]

In its 2019 coverage of the island, National Geographic provided this summary of the ownership and current situation:[8]

"after years of neglect by the previous laird, or estate owner, the people gained ownership themselves in 1997. Now, visitors to the nicknamed “People’s Republic of Eigg” contend with nothing more dangerous than negotiating walking territory with sheep or engaging in cheeky yet informative banter with Charlie Galli, the sole taxi driver and self-proclaimed 'Eigg Gazette'" ... there is a single main road ... and a single stoplight ... to alert everyone when electricity is running low ... humble attractions like the tiny post-office-turned-museum detailing island history; a wee, closet-size shed boasting handcrafted curiosities for sale by the honor system; herds of distrustful sheep; and pit stops such as “Rest and Be Thankful,” a patio tea garden open only when the sun shines.

Economy and transport

[edit]Key

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tourism is important to the local economy, especially in the summer months, and the first major project of the Heritage Trust was An Laimhrig, a new building near the jetty to house the island's shop and post office, Galmisadale Bay restaurant and bar, a craft shop, and toilet and shower facilities, which are open 24 hours a day.[124] A'Nead Hand Knitwear is a new island business making garments such as cobweb shawls and scarves.[125]

Conde Nast Traveller particularly recommends that visitors explore the Singing Sands beach, "dark Cathedral and Massacre caves, the abandoned village of Grulin or the island’s most distinctive sight, the near vertically-sided volcanic plug of An Sgùrr".[7]

There are two ferry routes to the island. There is a sheltered anchorage for boats at Galmisdale in the south of the island. In 2004 the old jetty there was extended to allow a roll-on roll-off ferry to dock. The Caledonian MacBrayne ferry MV Lochnevis sails a circular route around the four "Small Isles"—Eigg, Canna, Rùm and Muck from the fishing port of Mallaig. Arisaig Marine also runs a passenger ferry called the MV Sheerwater from April until late September from Arisaig on the mainland.[126]

Around 2014 a beer brewery called Laig Bay Brewing was set up on the island.[127][128]

In November 2017, a crew from the American television news magazine 60 Minutes visited Eigg. Its report stated that there was "one grocery shop, one primary school for five students and one pub at the tea room down by the wharf. The island's tiny electrical grid powers it all ... a combination of wind, hydroelectric and solar".[129]

Electrification project

[edit]The Heritage Trust provisioned a mains electricity grid, powered from near 100% renewable energy sources.[130] Previously, the island was not served by mains electricity and individual crofthouses had wind, hydro or diesel generators and the aim of the project is to develop an electricity supply that is environmentally and economically sustainable.

The new system incorporates a 9.9 kWp PV system, three hydro generation systems (totalling 112 kW) and a 24 kW wind farm supported by stand-by diesel generation, ultra-capacitors,[131] flywheels and batteries to guarantee continuous availability of power. A load management system has been installed to provide optimal use of the renewables. This combination of solar, wind and hydro power should provide a network that is self-sufficient and powered 98 percent from renewable sources. On 1 February 2008 the system was switched on.[132]

Eigg Electric generates a finite amount of energy and so Eigg residents agreed from the outset to cap electricity use at 5 kW at any one time for households, and 10 kW for businesses. If renewable resources are low, for example when there is less rain or wind, a "traffic light" system asks residents to keep their usage to a minimum. The traffic light reduces demand by up to 20 percent and ensures that there's always enough energy for everyone.[133]

The Heritage Trust has formed a company, Eigg Electric Ltd, to operate the new £1.6 million network, which has been part funded by the National Lottery and the Highlands and Islands Community Energy Company.[134][135]

Other sustainability projects

[edit]

In September 2008, Eigg began a year-long series of projects as part of their success as one of ten finalists in NESTA's Big Green Challenge. While the challenge finished in September 2009, the work to make the island "green" is continuing with solar water panels, alternative fuels, mass domestic insulation, transport and local food all being tackled.[136] In May 2009, the island hosted the "Giant's Footstep Family Festival", which included talks, workshops, music, theatre and advice about what individuals and communities can do to tackle climate change.[137]

In January 2010, Eigg was announced as one of three joint winners in NESTA's Big Green Challenge, winning a prize of £300,000. Eigg also won the prestigious Ashden UK Gold Award in July 2010.[138]

Lighthouse

[edit] Eilean Chathastail lighthouse viewed from the Mallaig-Eigg ferry. | |

| |

| Location | Eilean Chathastail, Highland, United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 56°52′15″N 6°07′17″W / 56.87091°N 6.12139°W |

| Tower | |

| Constructed | 1906 |

| Designed by | David Alan Stevenson, Charles Alexander Stevenson |

| Construction | metal (tower) |

| Height | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Shape | cylinder |

| Markings | white |

| Power source | solar power |

| Operator | Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust |

| Light | |

| Focal height | 24 m (79 ft) |

| Range | 8 nmi (15 km; 9.2 mi) |

| Characteristic | Fl W 6s |

Eigg lighthouse is an active lighthouse located on the south-eastern corner of the islet of Eilean Chathastail, one of the smaller Small Isles about 110 metres (360 ft) off Eigg.[139] The lighthouse was built in 1906 to a design by David A. and Charles Alexander Stevenson; it is a cylindrical metal tower only 8 metres (26 ft) high with gallery and lantern painted white. It is a minor light among those owned by Northern Lighthouse Board but day-to-day management rests with the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. The light emits a white flash every 6 seconds.

Wildlife

[edit]

An average of 130 species of birds are recorded annually. The island has breeding populations of various raptors: golden eagle, buzzard, peregrine falcon, kestrel, hen harrier and short and long-eared owl. Great northern diver and jack snipe are winter visitors, and in summer cuckoo, whinchat, common whitethroat and twite breed on the island.[140][141]

See also

[edit]- Religion of the Yellow Stick

- List of lighthouses in Scotland

- List of Northern Lighthouse Board lighthouses

- List of community buyouts in Scotland

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Broderick offers the Norse egg or eggjar, meaning "edge", although there is no evidence of Norse activity in the area until after Adomnan's time.[18] Watson points out that there "is another Eilean Eige, much notched, off the coast of Arisaig".[19] The Ravenna Cosmography, created around 700 AD is difficult to interpret. It has been suggested that "Sobrica" listed there could refer to Eigg, although there is clearly no linguistic connection between the names.[20]

- ^ An image of the Pictish design is located here.

- ^ The marriage had by now produced three sons: Ranald, John and Godfrey<[52] but John and Robert II of Scotland made an arrangement by which John divorced Amie and married Robert's daughter, Margaret Stewart. The divorce took place in 1350, not long after Amie's inheritance of Garmoran.[51]

- ^ Donald was appointed "contrary to the opinion of the men of Innsigall". MacPherson quoting W. F. Skene.[55]

- ^ Translation from Lowland Scots: "a good land with a parish church and many gannets; very good for sheep, with a good harbour for Highland galleys".

- ^ MacPherson notes that the Gaelic Uamh Fhraing is usually translated as the Cave of Francis but that "no reasonable explanation" exists for this and that "an etymology which connected them with the local physical features or with the event which occurred would be more in accordance with Gaelic topography. [61]

- ^ For example, by Boswell in 1773, by Sir Walter Scott in 1814, and Hugh Miller in 1845.[67][68]

- ^ As happened in 2017, when tourists discovered bones that turned out to be from a single 16 year old.[69]

- ^ A Free Church minister of Eigg stated "the less I enquired into its history... the more I was likely to feel I knew something about it".[70][71]

- ^ MacLean was imprisoned in Edinburgh by James VI for this attack but was allowed to escape and faced no further punishment.[73][74]

- ^ Fr. Cornelius Ward's 1625 report made no reference to events at "massacre cave", perhaps surprising given that if it were literally true everyone on the island over forty-eight would have been an incomer.[70]

- ^ According to Clan Ranald tradition there was large scale rape and murder on Eigg.[78][79] Captain Pottinger's ship's log does not mention these events and Clan Ranald traditions claim he tampered with the log to cover them up.[78]

- ^ In his 1967 history John S. Gibson commented that "The lists of government prisoners of the '45 confirm this tale, including as they do the names of sixteen Eigg men, marked as prisoners from the 2nd of June, and for transportation to the Barbadoes" [which] means that the rest had died in the misery of their imprisonment."[84]

- ^ which grew by only 4%, to a population of 103,702

- Citations

- ^ a b Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- ^ "New baby helps boost Isle of Eigg's population". BBC News. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 134–35

- ^ a b Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- ^ "History A Snapshot of the Small Isles History". Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ 60 Minutes (US TV series), 26 November 2017

- ^ a b "The 20 Most Beautiful Islands to visit in Scotland". Condé Nast Traveler. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b Bernabe, Danielle (26 April 2019). "Visit a wild and beautiful Scottish island owned by its residents". www.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Troll, Valentin R.; Emeleus, C. Henry; Nicoll, Graeme R.; Mattsson, Tobias; Ellam, Robert M.; Donaldson, Colin H.; Harris, Chris (24 January 2019). "A large explosive silicic eruption in the British Palaeogene Igneous Province". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 494. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9..494T. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35855-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6345756. PMID 30679443.

- ^ "Eigg beach runner stumbles on dinosaur bone". BBC. 26 August 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Panciroli, Elsa; Funston, Gregory F.; Holwerda, Femke; Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Foffa, Davide; Larkin, Nigel; Challands, Tom; Depolo, Paige E.; Goldberg, Daniel; Humpage, Matthew; Ross, Dugald; Wilkinson, Mark; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2020). "First dinosaur from the Isle of Eigg (Valtos Sandstone Formation, Middle Jurassic), Scotland". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 111 (3): 157–172. Bibcode:2020EESTR.111..157P. doi:10.1017/S1755691020000080. hdl:20.500.11820/5845a3b3-3e9c-4a6a-9d2d-dda833d3524e.

- ^ a b "1:50000 Sheet 60 (Scotland) Rum Solid and Drift Geology". BGS mapping portal. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Harvie-Brown, J. A. and Buckley, T. E. (1892), A Vertebrate Fauna of Argyll and the Inner Hebrides. Pub. David Douglas., Edinburgh. Facing P. LVI.

- ^ Banks 1977, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Banks 1977, p. 15.

- ^ Youngson (2001) p. 66

- ^ O'Clery (1864) p. 105

- ^ a b c Broderick (2013) p. 10

- ^ a b Watson (1926) p. 85

- ^ Youngson (2001) pp. 62-64

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) pp. 45-46

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Loch nam Ban Mora (22148)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b Martin, Martin. "Description of the Western Isles: A Description of the Isle of Egg". The Appin Regiment. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) pp. 30,52,78

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 60

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Rubh' An Tangaird (149414)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Galmisdale (215188)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Galmisdale Bay (301160)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Kildonnan (22147)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Struidh (255803)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Garbh Bealach (269299)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Poll Duchaill (202968)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Rudha Na Crannaig (22177)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Galmisdale (22171)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Hunter 2000, p. 64.

- ^ Watson 1926, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 136.

- ^ Munro, Alistair (14 August 2012). "Monastery where Christian saint was martyred is uncovered on Eigg". The Scotsman. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ John Hunter (2012) Excavations at Kildonnan, Eigg. University of Birmingham

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Kildonnan, St Donnan's Church And Burial-ground (22152)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Laig (22145)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Kildonnan (22155)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Laig (22163)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Laig (22164)". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Gregory 1881, pp. 9–17.

- ^ Woolf (2006) p. 103

- ^ Rixson 2001, p. 93.

- ^ "Treaty of Perth 1266". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Rixson 2001, p. 89-90.

- ^ Rixson 2001, p. 95.

- ^ a b Oram 2006, p. 124.

- ^ Gregory 1881, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Macdonald, Angus and Archibald, The Clan Donald (1896) p. 134

- ^ Rixson 2001, pp. 95–96.

- ^ MacPherson 1878, p. 579.

- ^ Rixson 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Gregory 1881, p. 65.

- ^ Gregory 1881, p. 102.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Munro, D. (1818) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland called Hybrides, by Mr. Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, who travelled through most of them in the year 1549. Miscellanea Scotica, 2. Quoted in Banks (1977) p. 190

- ^ a b MacPherson 1878, p. 580.

- ^ Banks 1977, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Rixson 2001, p. 114.

- ^ a b Dressler 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Banks 1977, p. 56.

- ^ Dressler 2007, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Banks 1977, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Lynn Forest-Hill, "Underground Man", Times Literary Supplement 14 January 2011 p. 15

- ^ Urbanus, Jason (July–August 2017). "A dangerous island". Archaeology. 70 (4): 14. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Banks 1977, p. 57.

- ^ Kieran, Ben. Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, 2007 ISBN 0-300-10098-1. p. 14

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 16.

- ^ John Lorne Campbell, Canna: The Story of a Hebridean Island, 2014, Birlinn Ltd

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 17.

- ^ MacPherson 1878, p. 581.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 25.

- ^ a b Allan I. MacInnes, Clan Massacres and British State Formation, in The Massacre in History, edited by Mark Levene / Penny Roberts, Berghahn Books, 1999

- ^ Odo Blundell (1917), The Catholic Highlands of Scotland, Volume II, pp. 192-193.

- ^ a b Banks 1977, p. 64.

- ^ Dressler 2007, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Campbell (1971), Highland Songs of the Forty-Five, p. 39.

- ^ Robert Forbes (1895), The Lyon in Mourning: Or a Collection of Speeches, Letters, Journals Etc., Relative to the Affairs of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. Volume III, Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society. Pages 84-88.

- ^ John S. Gibson (1967), Ships of the Forty-Five: The Rescue of the Young Pretender, Hutchinson & Co. London. p. 53.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Eigg, Kildonnan, Mill (106075)". Canmore.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 64.

- ^ "Eachdraidh mu Dhòmhnallaich Lathaig". Tobar an Dualchais. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b Dressler 2007, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Dressler 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Arlidge, John (28 January 1994). "Eigg owner says violent campaign has made him sell". The Independent. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Derek S. Thomson (1983), The Companion to Gaelic Scotland, page 169.

- ^ Edited by Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle (2020), North American Gaels: Speech, Song, and Story in the Diaspora, McGill-Queen's University Press. Pages 288-289.

- ^ Ronald Black (2002), Eilein na h-Òige: The Poems of Fr. Alllan MacDonald, Mungo Books. Page 64.

- ^ John Lorne Campbell, The Sources of the Gaelic Hymnal, 1893, The Innes Review, December 1956 Vol. VII, No. 2, pp. 101-111.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 45.

- ^ "Eigg World War I soldiers". Chomunn Eachdraidh Eige/Eigg History Society. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ MacDonald 2015, pp. 427–429, 472–473.

- ^ a b c d Dressler 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Banks 1977, p. 170.

- ^ Rixson 2001, p. 98.

- ^ "Ruined Church at Kildonnan". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 23 July 2024

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 23.

- ^ "Massacre and Cathedral Caves of Eigg". Walk Highlands. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Walk: Eigg caves – massacres & masses". Scotland Off the Beaten Track. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ Odo Blundell (1917), The Catholic Highlands of Scotland, Volume II, pp. 198-199.

- ^ "Eigg, St. Donan Catholic Church". The Roman Catholic Diocese of Argyll and the Isles. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ a b Dressler 2007, p. 41.

- ^ a b Dressler 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 69.

- ^ Dressler 2007, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Dressler 2007, p. 76.

- ^ "Maruma, the mysterious laird of Eigg".

- ^ Alastair McIntosh (2001). Soil and Soul: People Versus Corporate Power. Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1854108029.[page needed]

- ^ "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Scott, Kirsty (4 August 2003). "Scrambled Dreams on Eigg". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Patrick Barkham (26 September 2017). "This island is not for sale: how Eigg fought back". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Kroft, Steve (26 November 2017). "The Isle of Eigg". CBS News.

- ^ Kroft, Steve (24 June 2018). "60 Minutes' adventure to the Isle of Eigg". CBS News.

- ^ "Eigg Shop and Post Office" Archived 2009-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ "A'Nead Hand Knitwear" anead-knitwear.co.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ "Island Ferry and timetable > Isle of Eigg". arisaig.co.uk. Arisaig Marina. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "A newborn baby pushes a tiny, fascinating Scottish island's population to 105 (we think)". TheJournal.ie. 23 April 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Baynes, Richard (13 August 2016). "The islanders who took control and transformed beaten Eigg". The Herald. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "60 Minutes adventure to the Isle of Eigg". CBS News. 8 September 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Eigg Electric". Friends of the Earth Scotland. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Annie Smith (13 November 2018). "Eigg Toasts New Ultracapacitor System and Unscrambles the Power Grid". Ochaye6dot5. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Ross, John (31 January 2008). "Island finally turns on to green mains Eigg-tricity". The Scotsman. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Gardiner, Karen (30 March 2017). "The small Scottish isle leading the world in electricity". BBC Future. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Isle of Eigg, Inner Hebrides, Scotland - 2007" Wind and Sun Ltd. Retrieved 20 September 2007. Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Island energised by lottery cash". BBC News. 16 November 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Green Eigg islanders earn place in UK's Big Challenge says Press and Journal" islandsgoinggreen.org. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "Take Giant Green Footsteps to Eigg's Family Festival" Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Senscot. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ Ottery, Christine (1 July 2010). "Eigg Islanders win top prize for green living". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Rowlett, Russ. "Lighthouses of Scotland: Highlands". The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Eigg-ceptional summer". Scottish Wildlife (November 2007) No. 63 page 4.

- ^ "Bird watching on Eigg" Archived 2009-02-23 at the Wayback Machine Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- General references

- Banks, Noel (1977). Six Inner Hebrides. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7368-4.

- Barkham, Patrick (26 September 2017). "This island is not for sale: how Eigg fought back". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Broderick G., 2013, Some Island Names in the Former 'Kingdom of the Isles': A Reappraisal. The Journal of Scottish Name Studies 7:1-28.

- Dressler, Camille (2007). Eigg: The Story of an Island. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Gregory, Donald (1881). The History of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland 1493–1625 (2008 reprint by Birlinn ed.). Edinburgh: Thomas D. Morrison. ISBN 1-904607-57-8.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Hunter, James (2000). Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- MacDonald, Jo, ed. (2015). Cuimhneachan: Bàrdachd a' Chiad Chogaidh/Remembrance: Gaelic Poetry of World War One. Stornoway: Acair Books.

- MacPherson, Norman (1878). "Notes on antiquities from the island of Eigg". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 12. Edinburgh University. doi:10.9750/PSAS.012.577.597. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- O'Clery, Michael (1864). "The martyrology of Donegal: a calendar of the saints of Ireland". Trans. John O'Donovan. Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society.

- Oram, Richard (2006). "The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545". In Omand, Donald (ed.). The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Rixson, Denis (2001). The Small Isles: Canna, Rum, Eigg and Muck. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Watson, William J. (1926). The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (2005 reprint by Birlinn ed.). Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons.

- Woolf, Alex "The Age of the Sea-Kings: 900–1300" in Omand, Donald (2006) The Argyll Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-480-0

- Youngson, Peter (2001) Jura: Island of Deer. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-136-4

External links

[edit]56°54′N 6°10′W / 56.900°N 6.167°W

- The island's website

- Isle of Eigg History Society

- Geology of Eigg

- BBC Radio 4 – Open Country

- BBC Action Network - My story: Bringing power to the people

- Ashden Awards Case Study, video and photographs Archived 31 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Book about the role of incomers on the island and photogallery

- The Cruise of the Betsey- Account of Miller's voyage.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Eigg". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Eigg". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.