Hurricane Wilma

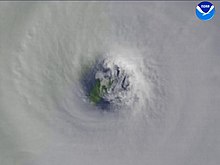

Wilma at its record peak intensity northeast of Honduras on October 19 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 15, 2005 |

| Extratropical | October 26, 2005 |

| Dissipated | October 27, 2005 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 185 mph (295 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 882 mbar (hPa); 26.05 inHg (Record low in the Atlantic basin) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 52 total |

| Damage | $26.5 billion (2005 USD) |

| Areas affected |

|

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History

Effects Other wikis | |

Hurricane Wilma was the most intense tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin and the second-most intense tropical cyclone in the Western Hemisphere, both based on barometric pressure, after Hurricane Patricia in 2015. Wilma's rapid intensification led to a 24-hour pressure drop of 97 mbar (2.9 inHg), setting a new basin record. At its peak, Hurricane Wilma's eye contracted to a record minimum diameter of 2.3 mi (3.7 km). In the record-breaking 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, Wilma was the twenty-second storm, thirteenth hurricane, sixth major hurricane,[nb 1] fourth Category 5 hurricane, and the second costliest in Mexican history.

Its origins came from a tropical depression that formed in the Caribbean Sea near Jamaica on October 15, headed westward, and intensified into a tropical storm two days later, which abruptly turned southward and was named Wilma. Wilma continued to strengthen, and eventually became a hurricane on October 18. Shortly thereafter, explosive intensification occurred, and in only 24 hours, Wilma became a Category 5 hurricane with wind speeds of 185 mph (295 km/h). Wilma's intensity slowly leveled off after becoming a Category 5 hurricane, and winds had decreased to 150 mph (240 km/h) before it reached the Yucatán Peninsula on October 20 and 21. After crossing the Yucatán, Wilma emerged into the Gulf of Mexico as a Category 2 hurricane. As it began accelerating to the northeast, gradual re-intensification occurred, and the hurricane was upgraded to Category 3 status on October 24. Shortly thereafter, Wilma made landfall in Cape Romano, Florida, with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). As Wilma was crossing Florida, it briefly weakened back to a Category 2 hurricane, but again re-intensified as it reached the Atlantic Ocean. The hurricane intensified into a Category 3 hurricane for the last time, before weakening while accelerating northeastward. By October 26, Wilma transitioned into an extratropical cyclone southeast of Nova Scotia.

Early in Wilma's duration, flooding and landslides caused 12 deaths in Haiti and 1 death and about $93.5 million in damage in Jamaica.[nb 2] The Yucatán Peninsula experienced intense winds, torrential precipitation, and high storm surge. Wilma damaged 28,980 homes and 473 schools. The hurricane caused $4.6 billion in damage and eight deaths in Mexico. In Cuba, the storm damaged crops, roads, railways, 7,149 homes, 364 schools, and 3 hospitals. A total of 446 dwellings were destroyed. Damage throughout Cuba reached about $704 million. In Florida, strong winds impacted much of the southern portions of the state, while storm surge led to coastal flooding, especially in Collier and Monroe counties. The former, where the storm made landfall, suffered about $1.2 billion in damage, with 16,000 businesses and homes impacted to some degree. In the Miami metropolitan area, Palm Beach County reported damage to nearly 59,000 businesses and homes, while 5,111 residences in Broward County and at least 2,059 others in Miami-Dade County became uninhabitable. Approximately $19 billion in damage and 30 deaths occurred in Florida. Within the Bahamas, Wilma caused one death and damaged or destroyed hundreds of homes, mostly on Grand Bahama. Overall, at least 52 deaths were reported and damage totaled to $26.5 billion, most of which occurred in the United States.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

In mid-October 2005, a large monsoon-like system developed in the Caribbean Sea. A broad low pressure area formed on October 13 to the southeast of Jamaica, which slowly became more defined while acquiring additional deep convection. On October 15 at 18:00 UTC, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) classified the system as Tropical Depression Twenty-Four while located about 220 mi (350 km) east-southeast of Grand Cayman. The depression drifted west-southwestward through a favorable environment, including warm sea surface temperatures, due to a high-pressure area over the Gulf of Mexico, a mid-tropospheric anticyclone to the east-northeast of the storm, and weak and poorly-defined steering flow. The depression turned southwestward and strengthened into a tropical storm on October 17, whereupon the NHC designated it Wilma. Initial intensification was slow, due to Wilma's large size and a flat pressure gradient, although the associated convection gradually organized.[2]

On October 18, Wilma curved west-northwestward and intensified into a hurricane, and subsequently underwent explosive deepening over the open waters of the Caribbean Sea. In a 30–hour period through October 19, Wilma's barometric pressure dropped from 982 to 882 millibars (29.0 to 26.0 inHg); this made Wilma the most intense Atlantic hurricane on record, based on pressure. During the same intensification period, the winds increased to a peak intensity of 185 mph (295 km/h), making Wilma a Category 5 on the Saffir–Simpson scale. An eyewall replacement cycle caused Wilma to weaken below Category 5 status on October 20. The storm then drifted northwestward toward Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula as a result of an increase in mid-level ridging to the northeast. Late on October 21, Wilma made landfall on the island of Cozumel, Quintana Roo, with sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). About six hours later, 03:30 UTC the next day, Wilma made a second landfall on the Mexican mainland near Puerto Morelos, but with winds reduced to 135 mph (215 km/h).[2]

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Pressure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPa | inHg | |||

| 1 | Wilma | 2005 | 882 | 26.05 |

| 2 | Gilbert | 1988 | 888 | 26.23 |

| 3 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 | 26.34 |

| 4 | Rita | 2005 | 895 | 26.43 |

| 5 | Milton | 2024 | 897 | 26.49 |

| 6 | Allen | 1980 | 899 | 26.55 |

| 7 | Camille | 1969 | 900 | 26.58 |

| 8 | Katrina | 2005 | 902 | 26.64 |

| 9 | Mitch | 1998 | 905 | 26.73 |

| Dean | 2007 | |||

| Source: HURDAT[3] | ||||

The hurricane weakened over the Yucatán Peninsula to Category 2 intensity, but gradually re-strengthened once it reached the Gulf of Mexico, despite a significant increase in wind shear. Wilma re-intensified into a Category 3 hurricane early on October 24 as it accelerated to the northeast, steered by a powerful trough. After passing northwest of the Florida Keys, the hurricane struck southwestern Florida near Cape Romano around 10:30 UTC with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). Wilma rapidly crossed the state and weakened to a Category 2 hurricane, emerging into the Atlantic Ocean near Jupiter. The cyclone briefly re-intensified to a Category 3 hurricane while passing north of the Bahamas later on October 24 while absorbing the smaller Tropical Storm Alpha to the east. The hurricane passed west of Bermuda on October 25. After cold air and wind shear penetrated the core of convection, Wilma transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on October 26 approximately 230 mi (370 km) southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, before it was absorbed by another extratropical storm a day later over Atlantic Canada.[2]

Records

At 18:01 UTC on October 19, a dropsonde from a hurricane hunter measured a barometric pressure of 884 mbar (26.1 inHg) in the eye of Wilma, along with sustained winds of 23 mph (37 km/h); the wind value suggested that the central pressure was slightly lower, estimated at 882 mbar (26.0 inHg). This is the lowest central pressure on record for any Atlantic hurricane,[2] breaking the previous record of 888 mbar (26.2 inHg) set by Hurricane Gilbert in 1988.[4] Wilma's intensification rate broke all records in the basin, with a 24–hour pressure drop of 97 mbar (2.9 inHg); this also broke the record set by Gilbert. At the hurricane's peak intensity, the Hurricane Hunters estimated the eye of Wilma contracted to a record minimum diameter of 2.3 mi (3.7 km).[2]

While striking Mexico, it dropped torrential rainfall on the offshore Isla Mujeres. Over 24 hours, a rain gauge recorded 64.330 in (1,633.98 mm) of precipitation, which set a record in Mexico for the nation's highest 24–hour rainfall total, as well as the highest 24–hour rainfall total in the western hemisphere.[5][6]

When Tropical Storm Wilma formed on October 17,[2] it became the 21st named storm of 2005 season, which broke the record for most tropical cyclones in a single season, 20, set in 1933.[7] An additional unnamed subtropical storm was added to 2005's tally after the season was over,[8] making Wilma actually the 22nd storm of the season. With Wilma, an entire alphabetic 21-name list was fully used up for the first time, necessitating the naming of subsequent storms in that season by letters of the Greek alphabet. No season would again have 22 storms or make use of the Greek alphabet for storm names until 2020.[9]

Preparations

The various governments of the nations threatened by Wilma issued many tropical cyclone warnings and watches. At 09:00 UTC on October 16, a hurricane watch and tropical storm warning were posted for the Cayman Islands; these were dropped three days later. A tropical storm warning was issued in Honduras from the border with Nicaragua westward to Cabo Camaron at 15:00 UTC on October 17. In Belize, another tropical storm warning became in effect at 15:00 UTC on October 19 from the border with Mexico to Belize City. On October 21, the tropical storm warning in Honduras was discontinued at 03:00 UTC, while the other in Belize was canceled twelve hours later.[2]

The Mexican government issued hurricane warnings from Chetumal near Belize to San Felipe, Yucatán; a tropical storm warning was extended westward to Celestún.[2] Officials declared a state of emergency in 23 municipalities across the Yucatán,[10] and placed Quintana Roo and Yucatán under a red alert, the highest on its color-coded alert system.[11] About 75,000 people evacuated in northeastern Mexico, including about 45,000 people who rode out the storm in 200 emergency shelters, many of them tourists.[12] Schools were canceled in Quintana Roo, Yucatán, and Campeche, up to 15 days in some areas.[13] Los Premios MTV Latinoamérica – the MTV Video Music Awards Latinoamérica – were canceled due to the hurricane, originally scheduled to occur in Playa del Carmen on October 20.[14]

The Cuban government issued several watches and warnings in relation to Wilma. By October 22, a hurricane warning was in place for the city of Havana, as well as the provinces of La Habana and Pinar del Río. A tropical storm warning was also issued for Isla de la Juventud, and a hurricane watch was issued for Matanzas Province.[2] The Cuban government mobilized 93,154 workers to help evacuate 760,168 people across the island's western provinces. The evacuees generally stayed with family, friends, or in storm shelters.[15] Officials closed all schools nationwide during the passage of Wilma and later Tropical Storm Alpha. During Wilma's passage, 41 hotels closed, of which five remained closed for two weeks after the storm. Many businesses, banks, and government institutions were closed for several days due to the storm. Along the coast, 554 boats were moved to protect them during the storm. Farmers moved 246,631 livestock, more than half of them cattle, to avoid the expected high waters. Passenger travel was halted for all trains nationwide, as well as ferry service between Batabanó and Isla de la Juventud. Poor weather conditions forced three airports to briefly close – José Martí International Airport in Havana, Juan Gualberto Gómez in Varadero and Jardines del Rey in Cayo Coco.[15][16]

The NHC issued tropical cyclone warnings and watches across much of southern Florida, with a hurricane warning ultimately covering all of South Florida from Longboat Key on the west coast to Titusville, including Lake Okeechobee and the Florida Keys. A tropical storm watch extended northward on the west coast to Steinhatchee River. On Florida's east coast, a tropical storm warning stretched northward from Titusville to St. Augustine, with a tropical storm watch extending north to Fernandina Beach.[2] Florida governor Jeb Bush declared a state of emergency on October 19, allowing the deployment of the Florida National Guard and strategic placement of emergency supplies.[17] A mandatory evacuation of residents was ordered for the Florida Keys in Monroe County and those in Collier County living west or south of U.S. Route 41.[18] County offices, schools and courts were closed October 24. At least 400 Florida Keys evacuated stayed at the Monroe County shelter at Florida International University in Miami-Dade County.[19] As far north as Flagler County, many schools and universities closed for at least one day in anticipation of the storm, including in Southwest Florida and the Miami, Orlando, and Tampa metropolitan areas.[20][21][22] Schools in Broward and Palm Beach counties remained closed for two weeks because of extended power outages and some damage to school buildings.[23]

Wilma's passage through Florida disrupted many festivals and sporting matches. Key West postponed Fantasy Fest, often held annually around Halloween, until December, resulting in only about one-third of the usual attendance figures and a loss of millions of dollars in revenue for hotels, restaurants, and stores.[24] The NFL moved the Kansas City Chiefs vs. Miami Dolphins game at Dolphins Stadium from October 23 to October 21,[25] while the NHL postponed the Florida Panthers vs. Ottawa Senators match at the BankAtlantic Center from October 22 to December 5. The NCAA rescheduled three college football games originally set to occur on October 22, with the Georgia Tech vs. Miami match moved to November 19, the West Virginia vs. South Florida game moved to December 3, and the Central Florida vs. Tulane game played on October 21, one day earlier.[26]

The government of The Bahamas issued a hurricane warning for the northwestern Bahamas at 12:00 UTC on October 23, about 24 hours before Wilma made its closest approach to the archipelago.[2] Officials ordered evacuations for the eastern and western portion of Grand Bahama island, with an estimated 300–1,000 people who ultimately evacuated to emergency shelters.[27][28] The hurricane halted production of Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, forcing the cast and crew to evacuate.[29][30]

The Bermuda Weather Service issued a gale warning for the island early on October 24, due to uncertainty whether Wilma would be tropical or not. After consulting with the NHC, the agency maintained the gale warning rather than changing it to a tropical storm warning to reduce confusion.[5]

Impact

| Region | Deaths | Damage (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| The Bahamas | 1 | $100 million |

| Cuba | 0 | $704 million |

| Haiti | 12 | $500,000 |

| Jamaica | 1 | $93.5 million |

| Mexico | 8 | $4.6 billion |

| United States | 30 | $21 billion |

| Total | 52 | $26.5 billion |

Caribbean

Greater Antilles

For several days in its formative stages, Wilma's outer rainbands dropped heavy rainfall in Haiti and as far east as the Dominican Republic. The rains triggered river flooding and landslides in Haiti, killing 12 people, and forcing 300 residents into shelters. The storm cut communications between Les Cayes and Tiburon.[2][31][32] Less than a week after Wilma formed, Tropical Storm Alpha struck Hispaniola and caused additional deadly floods in Haiti.[33] Damage in the country totaled around $500,000.[34]

Wilma caused one death in Jamaica as a tropical depression on October 16. It pounded the island for three days ending on October 18, flooding several low-lying communities and triggering mudslides that blocked roads and damaged several homes. Almost 250 people were in emergency shelters on the island.[35] Damage on the island totaled $93.5 million.[36]

While Wilma was moving northeast in the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane produced high tides and gusty winds across western Cuba. The highest recorded gust was 84 mph (135 km/h) at Casablanca near Havana.[2] For several days, the storm spread rainfall across 11 of Cuba's 14 provinces,[37] with a peak rainfall of 8.8 in (223 mm) in Pinar del Río province. The Cuban government tabulated the hurricane's economic cost at US$704.2 million, which included the expenses for preparations and lost production from factories. Nationwide, Wilma destroyed 446 houses and damaged another 7,149 to varying degree, mostly roofing damage.[15] Due to high floodwaters, nearly 250 people required rescue from their homes in Havana, using inflatable rafts and amphibious vehicles to reach the most severely flooded areas.[38] The hurricane wrecked 410 acres (167 ha) worth of agricultural products in Pinar del Río and Havana provinces,[39] which included damaged fruit trees, bee colonies, and tobacco houses. High floodwaters inundated parts of Havana and along Cuba's northwest coast, damaging roads and rail lines.[15] Landslides blocked two bridges and five roads in eastern Cuba.[37] The hurricane also damaged 364 schools and three hospitals. Officials cut electricity in Havana after winds reached 45 mph (72 km/h); after the storm, there were power and water outages in the city, nearby neighborhoods, and in Pinar del Río province.[15] The storm downed 146 power poles and 8.0 mi (12.9 km) worth of electric lines.[37]

Mexico

Across the Yucatán peninsula, Hurricane Wilma dropped torrential rainfall, inundated coastlines with a significant storm surge, and produced an extended period of strong winds. The hurricane lashed parts of the Yucatán peninsula with hurricane-force winds gusts for nearly 50 hours. On the Mexican mainland, a station in Cancún recorded 10–minute sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), with gusts to 132 mph (212 km/h) before the anemometer failed; gusts were estimated at 140 mph (230 km/h).[2][5][40] The prolonged period of high waves eroded beaches and damaged coastal reefs.[41][42]

Across Mexico, Wilma killed eight people – seven in Quintana Roo, and one in Yucatán.[43] Throughout Mexico, Wilma's total damage was estimated at $50 billion (MXN, US$4.6 billion), mostly in Quintana Roo, where it was the state's costliest natural disaster.[40][44] At the time, this made Wilma the costliest hurricane on record in Mexico, until it was surpassed by Hurricane Otis in 2023.[45] Wilma damaged 28,980 houses in Mexico,[41] and destroyed or severely damaged 110 hotels in Cancún alone.[46] In the city, about 300,000 people were left homeless.[47] The water level in Cancún reached the third story of some buildings due to 16 to 26 ft (5 to 8 m) waves, in addition to the storm surge.[48][49] About 300 people who were from Great Britain had to be evacuated when their shelter flooded in Cancún, while the Americans were left there by the United States.[50] The hurricane also caused significant damage in Cozumel and Isla Mujeres.[41] About 300,000 people lost power in Mexico.[13] The storm also damaged 473 schools.[41]

Flooding damaged houses in low-lying areas of eastern Yucatán state.[13] The primary highway connecting Cancún and Mérida, Yucatán was impassible after the storm due to floods.[51] Across Mexico, Wilma damaged 190 sq mi (490 km2) worth of crops, most of which was in Yucatán state.[41] Across the Yucatán peninsula, the hurricane downed about 1,000,000 acres (400,000 ha) of trees.[42]

United States

Florida

In Florida, Wilma's swift movement across the state resulted in mostly light precipitation totals of 3 to 7 in (76 to 178 mm), while some areas recorded only 1 to 2 in (25 to 51 mm) of rainfall or less.[2] However, precipitation in Florida peaked at 13.26 in (337 mm) at the Kennedy Space Center.[53] Additionally, the Lakeland Linder International Airport reported 7.53 in (191 mm) of rainfall on October 24, which remained the highest one-day total at that location until Hurricane Milton in 2024.[54] The highest observed sustained wind speed at surface-height was a 15-minute average of 92 mph (148 km/h) at a South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) observation site located in Lake Okeechobee, corresponding to a 1-minute average of 104 mph (167 km/h). Storm surge heights in the Florida Keys generally ranged from 4 to 8 ft (1.2 to 2.4 m) and peaked at nearly 9 ft (2.7 m) in Marathon. Collier County measured the highest storm surge on the mainland, reaching 4 to 8 ft (1.2 to 2.4 m) above sea-level. Wilma also spawned 12 tornadoes in Florida.[2][55] Another SFWMD site in southeastern Hendry County reported a minimum atmospheric pressure of 950.5 mbar (28.07 inHg).[2]

Wind damage accounted for much of the storm's overall damage.[2] The very large eye of Wilma moved across all of or portions of six counties – Broward, Collier, Hendry, Miami-Dade, and Palm Beach.[56] This resulted in widespread hurricane-force sustained winds and gusts, with Category 2 conditions likely occurring in southeastern Florida from Palm Beach County to northern Miami-Dade County.[2] Strong winds left widespread power outages; Florida Power & Light reported more than 3,241,000 customers had lost power throughout 42 counties.[57] At the time, this represented the largest power failure in the history of Florida.[2] The outages affected approximately 2.5 million subscribers in the Miami metropolitan area – roughly 98% of electrical customers in that area.[58]

Florida's agricultural industry reported around $1.3 billion in damage.[59] Nurseries and sugarcane crops were particularly hard hit – the former suffered damage totaling nearly $554 million and the latter experienced around $400 million in damage, approximately $30 million more than each of the 2004 Florida hurricanes combined. Additionally, citrus experienced roughly $180 million in damage from Wilma, equating to a loss of approximately 17% of citrus fruits.[60] Overall, Wilma left about $19 billion in damage and 30 deaths in Florida,[61][62] 5 from direct causes.[2] Consequently, the hurricane ranked as the then-fourth costliest tropical cyclone in the United States, behind only Ivan in 2004, Andrew in 1992, and Katrina earlier that year. This has been surpassed many times since then, however. Wilma also ranked as the second costliest hurricane in Florida at the time, behind only Andrew. Adjusted for inflation in the year 2017, Wilma would have caused about $24.32 billion in damage.[61]

In Monroe County, storm surge from Wilma impacted the Florida Keys twice, with the second event causing the worst coastal flooding in the island chain since Hurricane Betsy in 1965.[63] At Dry Tortugas National Park, storm surge and winds damaged boats, destroyed docking facilities, and flooded the park office and living quarters, but Fort Jefferson saw no major damage.[64] Water submerged roughly 60% of Key West and left approximately 690 apartment units, homes, and mobile homes uninhabitable.[24][65] Wilma damaged more than 4,100 single-family residences, 20 of which sustained major damage, and 6 experienced complete destruction. The hurricane also damaged roughly 2,500 mobile homes, with 257 suffering substantial impact and 15 being destroyed. About 90 apartment and condominium units received some degree of impact.[64] As many as 20,000 cars suffered damage,[65] prompting the Key West Citizen to refer to the lower Florida Keys as a "car graveyard."[63] The storm ran hundreds of vessels aground, including 223 boats between Key West and Islamorada.[65] Damage in Monroe County reached at least $200 million, with approximately half the total occurring in Key West, though the figure did not include incorporated areas.[66]

Storm surge in Collier County mostly impacted Chokoloskee, Everglades City, and Plantation Island. Surge destroyed around 200 recreational vehicles in Chokoloskee and covered Everglades City with about 4 ft (1.2 m) of water,[64] flooding structures including the Old Collier County Courthouse.[67] The hurricane also caused major impact in Naples, especially to 90 high-rise condos. Buildings in the city suffered $150 million in damage. Additionally, high winds severely damaged 100 hangars at Naples Airport. Wilma damaged 16,000 businesses and homes to some degree in Collier County,[68] with 394 buildings suffering damage to at least 50 percent of their structure. The hurricane destroyed 2 dwellings, 8 workplaces, and 615 mobile homes, about one-third in Immokalee.[69] In total, the county reported $1.2 billion in damage,[70] along with a death toll of 7.[62] Hurricane-force wind gusts extended northward into Lee County.[56] Bonita Springs experienced the worst impact in Lee County, with 972 homes reporting minor to major damage. In Cape Coral, Wilma impacted 511 residences; 490 dwellings suffered minor damage, 20 others experienced extensive damage, and 1 mobile home was destroyed. The storm also inflicted moderate to major damage to 78 businesses and demolished 1 other workplace.[70] Insured and uninsured damage in the county totaled $101 million and one fatality occurred.[56][62]

Wilma inflicted a multi-billion dollar disaster in the Miami metropolitan area, including $2.9 billion in damage in Palm Beach County,[71] $2 billion in Miami-Dade County, and $1.2 billion in Broward County.[72] Numerous homes and businesses experienced some degree of impact, with over 55,000 dwellings and 3,600 workplaces damaged in Palm Beach County alone.[71] Furthermore, officials declared 5,111 residences in Broward County and at least 2,059 others in Miami-Dade County as uninhabitable.[64][73] An aerial survey in Broward County indicated that 70% of homes and businesses in Coconut Creek, Davie, Margate, North Lauderdale, Plantation, and Sunrise experienced some degree of impact.[74] High winds also damaged skyscrapers and high-rises, including the Colonial Bank Building, the JW Marriott Miami, Espirito Santo Plaza, and the Four Seasons Hotel Miami in Greater Downtown Miami,[75][76] as well as the One Financial Plaza, AutoNation Tower, Broward Financial Center, the Broward County Administration Building, the 14-floor Broward County School Board building, and the Broward County Courthouse in Fort Lauderdale.[77]

In Hendry County, high winds damaged around 90 percent of buildings and homes in Clewiston and other eastern sections of the county.[69] The county suffered a loss of about half of orange and sugar crops.[78] Overall, Wilma substantially damaged 250 homes and destroyed 550 other homes in Hendry County.[69] Damage totaled at least $567 million, with $300 million to agriculture and $267 million in structures.[79] Hurricane-force wind gusts in Glades County left approximately 3,000 people without electricity. Wilma destroyed more than 60 homes.[80] Seventeen school district buildings suffered roof damage.[81] Approximately 800 residences sustained damage in Okeechobee County, with 114 receiving major damage and 29 others being destroyed. In Martin County, which recorded a wind gust as high as 108 mph (174 km/h) in Hobe Sound, the storm extensively damaged 120 dwellings and destroyed 48 others.[56] The county tallied $95.7 million in damage. Neighboring St. Lucie County reported damage totaling $43.4 million.[77] Rainfall totals ranging from 10 to 13 in (250 to 330 mm) in parts of Brevard County left freshwater flooding; about 200 homes in Cocoa suffered water damage.[56] Six tornadoes in the county also damaged or destroyed some apartments, cars, fences, power lines, restaurants, and trees.[56][55] In the Florida Panhandle, abnormal high tides generated by Wilma washed the Cape St. George Lighthouse into the Gulf of Mexico. Damage elsewhere in the state was generally minor.[56]

Other states

Rainfall from Hurricane Wilma extended up the east coast of the United States from Florida to Virginia. Precipitation reached 3 in (76 mm) along the Outer Banks of North Carolina.[82] As Wilma was moving out to sea, a nor'easter developed near Cape Hatteras; the two systems produced high waves, coastal flooding, and beach erosion from Delaware to Maine, resulting in some road closures. The nor'easter drew moisture and energy from Wilma to produce heavy rainfall, snowfall in higher elevations, and gusty winds, with a peak wind gust of 66 mph (106 km/h) recorded at Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory in Milton. The high winds resulted in downed trees and scattered power outages, with traffic blocked on parts of Interstate 95 in Rhode Island and the Green Line train in Newton, Massachusetts. Snowfall reached 20 in (510 mm) in Vermont. In Maine, the snowfall left about 25,000 people without power.[83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][excessive citations]

Bahamas and Bermuda

After exiting Florida, Wilma passed just north of the northwestern Bahamas.[2] A buoy just off West End on Grand Bahama recorded sustained winds of 95 mph (153 km/h), along with gusts of 114 mph (183 km/h). The hurricane also produced high waves and a 12 ft (3.7 m) storm surge,[5] which reached about 1,000 ft (300 m) inland in some areas. The sudden rush of water destroyed about 250 homes and damaged another 400, mostly on the western portion of Grand Bahama. At one home in Eight Mile Rock, the waters swept away and killed a 15-month-old infant. The flooding unearthed 54 bodies from five cemeteries. Flooding also inundated more than 500 vehicles. Central and eastern Grand Bahama received little to no damage from the hurricane. The undersecretary to the prime minister, Carnard Bethell, estimated monetary damage at "just maybe under $100 million".[91] However, the country estimated a damage total of about US$6.5 million in their report to the WMO. Damage in the Bahamas mostly consisted of torn roofs and uprooted trees,[5] along with downed poles and trees. Power and telephone services were disrupted throughout Grand Bahama.[28] Several resorts were closed for an extended period of time, after the winds blew out windows.[91][92] There were several traffic accidents, including an overturned bus, injuring the driver. During the passage of the hurricane, five cases of looting were reported, with one person caught and arrested.[93] On Bimini Island, the hurricane severely damaged a hotel and eight waterfront homes. On Abaco, Wilma destroyed several buildings, including a governmental clinic and eight homes.[94]

In Bermuda, Hurricane Wilma produced wind gusts of 51 mph (82 km/h). The strongest winds on the island were short-lived due to the hurricane's fast forward motion at the time. The hurricane disrupted the flight path of migratory birds, resulting in an unusual increase in frigatebird sightings around the island.[5]

Aftermath

Mexico

In Mexico, residents and tourists staying in shelters faced food shortages in Wilma's immediate aftermath.[49] There were 10 community kitchens set up across Cancún, each capable of feeding 1,500 people every day.[95] Local and federal troops quelled looting and rioting in Cancún.[47][96] While Cancún's airport was closed to the public, stranded visitors filled taxis and buses to Mérida, Yucatán. Located 320 km (200 mi) from Cancún, Mérida was the region's closest functioning airport.[97] Most hotels in Cozumel, Isla Mujeres, and the Riviera Maya were largely reopened by early January 2006.[98] The resorts in Cancún took longer to reopen, but most were operational by Wilma's one-year anniversary.[99]

On November 28, Mexico declared a disaster area for 9 of Quintana Roo's 11 municipalities – Benito Juárez, Cozumel, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Isla Mujeres, Lázaro Cárdenas, Othon P. Blanco, and Solidaridad.[41] Mexico's development bank – Nacional Financiera – provided financial assistance to businesses affected by Wilma and Stan through a $400 million fund (MXN, US$38 million). Quintana Roo's state government began a temporary work program for residents whose jobs were impacted by the hurricane.[95] The Mexican Red Cross provided food, water, and health care to residents affected by the hurricane. The agency also distributed emergency supplies, such as mosquito nets, plastic sheeting, and hygiene supplies.[100][10][51]

Cuba

Within a few days of Wilma's passage by Cuba, workers restored power and water access to impacted residents. The Revolutionary Armed Forces cleared and repaired roads around Havana that were flooded.[15] The capital city was reopened and largely returned to normal within six days of the storm.[101] On October 25, the government of the United States offered emergency assistance to Cuba, which the Cuban government accepted a day later. This acceptance of aid broke from previous practice; many times in the past, including during Hurricane Dennis, the United States offered aid, but the Cuban government declined.[102] The United States provided US$100,000 to non-governmental organizations in the country.[103]

United States

On October 24, 2005, the same day Wilma made landfall in Florida, President George W. Bush approved a disaster declaration for Brevard, Broward, Collier, Glades, Hendry, Indian River, Lee, Martin, Miami-Dade, Monroe, Okeechobee, Palm Beach, and St. Lucie counties. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) expended $342.5 million to the 227,321 approved applicants. The agency paid out $150.8 million for housing and $191.5 million for other significant disaster-related needs, including loss of personal property, moving and storage, and medical or funeral expenses relating to the hurricane. Public assistance from FEMA totaled over $1.4 billion, while grants for hazard mitigation projects exceeded $141.5 million.[104] Additionally, the federal government provided assistance via the Small Business Administration and United States Army Corps of Engineers. The former approved about $101.4 million in low-interest loans for businesses and homes and the latter installed more than 42,000 temporary roofs.[105]

Florida governor Jeb Bush activated an emergency bridge loan program in early November 2005, allowing small businesses damaged by Wilma to apply for interest-free loans up to $25,000.[106] The Florida legislature took several actions in the 2006 session in relation to Wilma. These included allocating $66.7 million to improving shelters, mandating that high-rise buildings have at least one elevator capable of operating by generator, and requiring gas stations and convenience stores to possess a back-up electrical supply in the event that they have fuel but no power.[107]

Florida's sugar industry was greatly affected; the cropping had already started and had to be halted indefinitely. Damage to sugarcane crops was critical and widespread. Citrus canker spread rapidly throughout southern Florida following Hurricane Wilma, creating further hardships on an already stressed citrus economy due to damage from Wilma and previous years' hurricanes. Citrus production estimates fell to a low of 158 million boxes for the 2005–2006 production seasons from a high of 240 million for 2003–2004.[108] Forecasts projected a decrease of 28 million boxes of oranges, the smallest crop since the 1989-1990 growing season, caused by a severe freeze.[109]

By late-September 2010, roughly $9.2 billion had been paid for more than 1 million insurance claims that had been filed throughout Florida in relation to Hurricane Wilma.[110]

Bahamas

By about two days after the passage of Hurricane Wilma, 800 residents on Grand Bahama remained in shelters.[28] Local Red Cross chapters mobilized all available resources to assist the residents most affected. The Bahamian Red Cross began a three-month program to distribute food and other items to 1,000 of the 3,500 affected families, primarily on Grand Bahama; the remaining 2,500 families received assistance from the government and other organizations. Volunteers delivered building materials and provided water vouchers to those affected. In Nassau, the Red Cross disaster contingency stock sent a boat with food items, blankets, health kits, tarpaulins and water.[111] About a week after the hurricane, the United States Agency for International Development began providing $50,000 to the Bahamian National Emergency Management Agency for the purchase and distribution of emergency supplies. The agency also provided $9,000 for locally contracted helicopter assessments in the affected areas.[112] Red Cross agencies throughout the Caribbean provided hygienic kits, plastic sheeting, blankets, and jerry cans.[111] Work crews quickly removed road debris and tree limbs, and by the day after the passage of Wilma most roads were cleared. The passage of the hurricane left 1,000–4,000 people and hundreds of animals homeless. In response, the Grand Bahama Humane Society distributed about 340 kg (750 lb) of dog food and treated or euthanized injured animals, depending on their condition.[113] Partly due to hurricane damage in tourist areas of Mexico, the Bahamas experienced a 10% increase in visitors in December 2005.[114] Electricians had power restored to the Freeport area by the day after the storm,[27] and had power restored to most of the western portion of the island within three weeks after the hurricane.[91] By that time, the airport on Grand Bahama was reopened, along with every hotel but one; the remaining hotel reopened two months after the hurricane.[115][116]

Retirement

Due to the hurricane's widespread damage, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name "Wilma" from the Atlantic hurricane naming lists in April 2006. It was replaced with "Whitney" for the 2011 Atlantic hurricane season.[117][118]

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2005

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Cuba hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes (2000–present)

- Timeline of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season

- Hurricane Allen (1980) – Another record-breaking Category 5 storm that moved through the Caribbean Sea

- Hurricane Gilbert (1988) – A Category 5 storm that previously held the record for the most intense Atlantic storm on record

- Hurricane Mitch (1998) – An extremely deadly Category 5 storm that affected similar areas

- Hurricane Delta (2020) – A Category 4 storm that rapidly intensified in the same area and struck the Yucatán Peninsula

- Hurricane Eta (2020) – A Category 4 hurricane that also rapidly intensified in the same area and devastated Central America

- Cyclone Ernie (2017) – One of the quickest strengthening tropical cyclones on record.

Notes

- ^ A major hurricane is a tropical cyclone that reaches at least Category 3 intensity on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[1]

- ^ All damage figures are in 2005 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- ^ "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Richard J. Pasch; Eric S. Blake; Hugh D. Cobb III; David P. Roberts (January 12, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Wilma (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ "Wilma Sets Barometric Pressure Record". Associated Press News. October 19, 2005. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Final Report of the RA IV Hurricane Committee Twenty-Eighth Session (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Randall Cerveny; Valentina Davydova Belitskaya; Pierre Bessemoulin; Miguel Cortez; Chris Landsea; Thomas C. Peterson (2007). "A New Western Hemisphere 24-hour Rainfall Record". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on December 18, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ Philip Klotzbach; Carl Schreck III; Gilbert Compo; Steven Bowen; Ethan Gibney; Eric Oliver; Michael Bell (March 1, 2021). "The Record-Breaking 1933 Atlantic Hurricane Season". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 102 (3). American Meteorological Society: E446 – E463. Bibcode:2021BAMS..102E.446K. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0330.1 (inactive December 2, 2024). S2CID 225148236.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Jack Beven; Eric S. Blake (April 10, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Unnamed Subtropical Storm (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Alpha". Greenbelt, Maryland: Goddard Space Flight Center. October 23, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico: Hurricane Wilma – Information Bulletin n° 3. International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (Report). October 21, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Mexico: El Presidente Vicente Fox estará en contacto permanente para ser informado de la evolución del huracán, Rubén Aguilar, vocero de Presidencia. Government of Mexico (Report) (in Spanish). October 21, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ The Caribbean: Hurricane Wilma OCHA Situation Report No. 5. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). October 24, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Orlando de Jesús Alva Gonzákes (2015). Evaluación de Daños en la Infraestructura de Quintana Roo y Yucatún Causados por el Huracán Wilma (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). National Autonomous University of Mexico. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ "Cancelación definitiva de los Premios MTV Latinoamérica". La Nacion (in Spanish). Vicente López, Buenos Aires Province. November 16, 2005. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Susana Lee (November 28, 2005). Cuba: Estimado en 704 millones 200 mil dólares el costo de los daños ocasionados por el huracán Wilma. Government of Cuba (Report) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2022 – via ReliefWeb.

- ^ "Hurricane Wilma grows in strength". BBC News. October 19, 2005. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Capt. Steve Alvarez (October 24, 2005). "Hurricane Wilma Makes Landfall in Florida". United States Department of Defense. American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Collier issues mandatory evacuation". Fort Myers, Florida: WBBH-TV. October 21, 2005. Archived from the original on January 12, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Only a Few Hours Remains for Keys Evacuation". Government of Monroe County, Florida. October 23, 2005. Archived from the original on October 24, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Hurricane Wilma News Release #1 – October 19th (as of 3:00 p.m.)" (PDF). Collier County Public Schools. October 19, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ "Threat Of Wilma Closes Schools Today". Daytona Beach, Florida: WESH. October 24, 2005. Archived from the original on January 9, 2006. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ Situation Report No. 12 – Hurricane Wilma (PDF) (Report). Florida State Emergency Response Team. October 24, 2005. pp. 3–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 28, 2005. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Florida Schools Shut by Wilma Reopen". Fox News. Associated Press. November 7, 2005. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Kennard Kasper (March 1, 2007). Hurricane Wilma in the Florida Keys (Report). National Weather Service Key West, Florida. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "Wilma causes Chiefs-Dolphins to reschedule for Friday". ESPN. Associated Press. October 20, 2005. Archived from the original on December 28, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Wilma postpones Georgia Tech-Miami, others". ESPN. Associated Press. October 19, 2005. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Bahamas Vacation Guide (December 14, 2005). "Hurricane Wilma Ravages Grand Bahama". Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Caribbean: Hurricane Wilma Emergency Appeal No. 05EA024". International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies. ReliefWeb. October 25, 2005. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Ben Fritz (July 9, 2006). "Pirates' treasure". Variety. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Patrick Williams (May 17, 2015). "Pirates of the Caribbean curse: Film franchise has disastrous history with fire, animals and Mother Nature". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Haiti Weather Hazards Assessment: October 20 - 26, 2005 (Report). Famine Early Warning System Network. October 20, 2005. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ^ Haiti: Floods - Information Bulletin n° 1 (Report). International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies. October 31, 2005. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020 – via ReliefWeb.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (January 4, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Alpha (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ Université Catholique de Louvain (2007). "EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database for the Caribbean". Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ "Wilma nears Cayman Islands". New Delhi, India: NDTV. October 19, 2005. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ Norman Harris (2006). "The Use of Nowcasting Technology for Natural Hazard Mitigation: The Jamaican Experience" (PDF). World Meteorological Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c The Caribbean: Hurricane Wilma OCHA Situation Report No. 8 (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. October 28, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Wilma barrels across Florida". The Denver Post. Associated Press. October 24, 2005. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Ricardo Zapata Martí (August 2006). Los Efectos De Los Desastres En 2004 Y 2005: La Necesidad De Adaptacion De Largo Plazo (in Spanish). United Nations Publications. p. 20. Archived from the original on September 14, 2024. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Alberto Hernández Unzón; M.G. Cirilo Bravo. Resumen del Huracán "Wilma" del Océano Atlático (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Características e Impacto Socioeconómico de los Principales Desastres Ocurridos en la República Mexicana en el Año 2005 (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Sistema Nacional de Protección Civil. August 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ a b ERD aids communities in Mexico after Hurricane Wilma. Episcopal Relief and Development (Report). November 1, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ "Wilma kills 8 in southeast Mexico". Xinhua News Agency via Comtex. October 23, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Jeff Masters; Bob Henson (October 27, 2023). "Acapulco reels from catastrophic damage in the wake of Hurricane Otis". Yale Climate Connections. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ Brad J. Reinhart; Amanda Reinhart (March 7, 2024). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Otis (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ "Hurricane death toll rises in Florida as residents face cleanup". Deutsche Presse Agentur. October 25, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b The Caribbean: Hurricane Wilma OCHA Situation Report No. 6. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). October 25, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ The Salvation Army in Mexico provides aid to victims of Hurricane Wilma. The Salvation Army (Report). November 1, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Hurricane Wilma devastates Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. World Vision (Report). October 25, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ "Huracán Wilma azota a balnearios de México y se acerca a Florida" (in Spanish). Reuters. October 20, 2005. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ a b The Caribbean: Hurricane Wilma OCHA Situation Report No. 7. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). October 26, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Dance, Scott; Ducroquet, Simon; Muyskens, John (September 26, 2024). "See how Helene dwarfs other hurricanes that have hit the Gulf Coast". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2024.

- ^ Roth, David M. (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ County Impacts Associated with Hurricane Milton (2024) (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Tampa Bay Area, Florida. October 15, 2024. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 29, 2024. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "20051023's Storm Reports". Storm Prediction Center. Norman, Oklahoma: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2005. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Tom Gwaltney (February 2018). Florida Power & Light Company Grid Hardening and Hurricane Response (PDF). Florida Power & Light (Report). United States Department of Energy. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Joseph Mann; Doreen Hemlock (October 25, 2005). "FPL to take 'up to 4 weeks'". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. p. 1B. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bush pushes federal farm aid". Florida Today. Cocoa, Florida. Associated Press. November 11, 2005. p. 1B. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Doreen Hemlock (November 10, 2005). "Seaports, growers hard hit by storm". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. pp. 1D and 8D. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c "30 Deaths in Florida". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida. November 6, 2005. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Timothy O'Hara; Sara Matthis (October 27, 2005). "Flooded cars litter the Keys". The Key West Citizen.

- ^ a b c d Hurricane Wilma Post-Storm Beach Conditions and Coastal Impact Report (PDF) (Report). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Environmental Protection. January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Jennifer Babson (November 11, 2005). "Keys Ask for 2,000 Trailers". Miami Herald. p. 1B. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ David Ball (October 26, 2005). "Damage could exceed $250M - Storm surge the main culprit". Florida Keys Keynoter. Marathon, Florida.

- ^ "Hurricane Wilma 2005". Coastal Breeze News. Marco Island, Florida. August 12, 2010. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Preliminary Storm Report...Hurricane Wilma (Report). National Weather Service Miami, Florida. November 29, 2005. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Wilma Damage By The Numbers". The News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. November 5, 2005. p. B2. Retrieved May 15, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Damage". The News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. November 6, 2005. p. A8. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Luis F. Perez; Angel Streeter; Ushma Patel (December 18, 2005). "Adding Up Wilma's Fury: $2.9 Billion Countywide - More than 55,000 Homes, 3,600 Businesses Damaged". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. p. 1A. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Trenton Daniel (October 24, 2006). "Year Later, Wilma's Wrath Still Visible". Miami Herald. p. 1B. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Natalie P. McNeal; Amy Sherman; Ashley Fantz; Daniel Chang (November 3, 2005). "Thousands Displaced; Agencies Strapped". Miami Herald. p. 29A. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "East coast to rebound". The News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. Knight Ridder. October 29, 2005. p. A4. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Teddy Kidder (October 25, 2005). "City-by-city Assessment Of Damage In South Florida". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brian Bandell; et al. (October 22, 2007). "Wrath of Wilma's aftermath still lingers two years later". Biz Journals. Charlotte, North Carolina. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Damage statewide". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida. November 6, 2005. p. 130. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bill Fabian (October 27, 2005). "Wilma Brings Devastation". The Clewiston News. p. 10. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Barbara S. Butler (November 8, 2005). "Hendry County Board of County Commissioners Tapes 2005-24 & 2005-25". Clewiston, Florida: Hendry County Board of County Commissioners. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 7, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Terry Brady (October 25, 2005). "Homes, roofs sustain damage in Moore Haven". The News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. p. A15. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thrice Hit – Learning From Others' Experience" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. January 20, 2011. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Roth, David (April 30, 2008). "Hurricane Wilma — October 22–24, 2005". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ^ "High Surf Delaware Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "High Surf New Jersey Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "New York Winter Storm Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Connecticut High Wind Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Rhode Island High Wind Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Massachusetts High Wind Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Vermont High Wind Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Maine Heavy Snow Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c Amy Royster (December 4, 2005). "Wilma's Waves Devastate Grand Bahama Communities". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida. Retrieved August 11, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lisa S. King (October 31, 2005). "Most Resorts Fared Well During Storm, But Not Xanadu Beach". Freeport News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ Jeremy Francis (October 27, 2005). "Freeport Sustained Considerable Damage From Hurricane Wilma". Freeport News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ Kevin Deutsch (November 1, 2005). "Islanders Assess Damage After Sea Takes Homes". The Palm Beach Post. p. 8A. Archived from the original on September 26, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Wilma: Inicia la reconstrucción mxm (martes)" (in Spanish). El Universal. October 26, 2005. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico: Hurricane Wilma – Information Bulletin n° 4. International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (Report). October 24, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Sofia Miselem (October 24, 2005). "After Wilma Hits Mexico, All Buses Lead To Merida". Terra Daily. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Will Weissert (January 5, 2006). "After the hurricane, Cancun still has a long way to go". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Chris Erskine (November 12, 2006). "Cancun, rebuilt and showing off". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Mexican Red Cross delivers immediate aid to victims of Wilma in the Yucatan Peninsula. International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (Report). October 24, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Fidel Rendón Matienzo (November 5, 2005). "Cuba: San Cristóbal de La Habana borra las huellas de Wilma" (in Spanish). Cuban News Agency. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Cuba accepts U.S. offer of hurricane assistance (Report). United States Department of State. October 27, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ U.S. offer of assistance to Cuba in the wake of Hurricane Wilma (Report). United States Department of State. November 2, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Hurricane Wilma: Ten Years Later". Federal Emergency Management Agency. October 22, 2015. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ USA: Floridians approved for more than $300 million in assistance for Wilma recovery (Report). Federal Emergency Management Agency. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ "Bridge loans available to businesses". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. November 4, 2005. p. 2D. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mary Ellen Klas (September 6, 2017). "Is South Florida more prepared than it was 12 years ago with Wilma?". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on September 27, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Kevin Bouffard (March 19, 2006). "1–2 Punch Hits Citrus". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ "Wilma slashes harvest of oranges 15 percent". The Gainesville Sun. Associated Press. December 10, 2005. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Julie Patel (September 28, 2010). "Deadline for Hurricane Wilma claims approaching". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ a b "Red Cross responds to 'Wilma' on Grand Bahama". Caribbean Red Cross Societies. November 1, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ "USAID provides assistance to The Bahamas hurricane victims". United States Agency for International Development. October 31, 2005. ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Elizabeth (Tip) Burrows (November 2005). "Hurricane Wilma and Grand Bahama". Pegasus Foundation. Archived from the original on July 19, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ Avery Johnson (December 4, 2005). "South Looks Up: Warm-weather destinations are seeing near-record highs for bookings, rates". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Laszlo Buhasz (November 12, 2005). "Caribbean hot spots sweep up in hurricanes' wake". The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Ontario. Archived from the original on September 26, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Jane Wooldridge (December 11, 2005). "Hurricane Report". Richmond Times Dispatch. p. J4. Archived from the original on September 26, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dennis, Katrina, Rita, Stan, and Wilma "Retired" from List of Storm Names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 6, 2006. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 2006. p. 3-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

External links

- Hurricane Wilma

- 2005 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2005 in Florida

- 2005 in Mexico

- 2005 natural disasters

- Atlantic hurricanes in Mexico

- Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricanes in Belize

- Hurricanes in Canada

- Hurricanes in Cuba

- Hurricanes in Florida

- Hurricanes in Honduras

- Hurricanes in Jamaica

- Hurricanes in the Bahamas

- Hurricanes in the Cayman Islands

- October 2005 events in North America

- Retired Atlantic hurricanes

- Tropical cyclones in 2005