Mount Edziza

| Mount Edziza | |

|---|---|

| Edziza Peak Edziza Mountain | |

The ice-filled summit crater of Mount Edziza | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,786 m (9,140 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 57°42′55″N 130°38′04″W / 57.71528°N 130.63444°W[2] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Unclear |

| Native name | Tenh Dẕetle (Tahltan)[3] |

| English translation | 'Ice Mountain'[3] |

| Geography | |

| |

| Location in Mount Edziza Provincial Park | |

| Country | Canada[1] |

| Province | British Columbia[1] |

| District | Cassiar Land District[2] |

| Protected area | Mount Edziza Provincial Park[4] |

| Parent range | Tahltan Highland[5] |

| Topo map | NTS 104G10 Mount Edziza[2] |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | 1.1 Ma to less than 20 ka[6][7] |

| Rock type(s) | Basalt, trachybasalt, tristanite, mugearite, benmoreite, trachyte, rhyolite[1][8] |

| Volcanic region | Northern Cordilleran Province[9] |

| Last eruption | Holocene age[7][10] |

Mount Edziza (/ədˈzaɪzə/ əd-ZY-zə; Tahltan: Tenh Dẕetle [ten̥ ˈdðetle]) is a volcanic mountain in Cassiar Land District of northwestern British Columbia, Canada. It is located on the Big Raven Plateau of the Tahltan Highland which extends along the western side of the Stikine Plateau. Mount Edziza has an elevation of 2,786 metres (9,140 feet), making it the highest point of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex and one of the highest volcanoes in Canada. However, it had an elevation of at least 3,396 metres (11,142 feet) before its formerly cone-shaped summit was likely destroyed by a violent eruption in the geologic past; its current flat summit contains an ice-filled, 2-kilometre-in diameter (1.2-mile) crater. The mountain contains several lava domes, cinder cones and lava fields on its flanks, as well as an ice cap containing several outlet glaciers which extend to lower elevations. All sides of Mount Edziza are drained by tributaries of Mess Creek and Kakiddi Creek which are situated within the Stikine River watershed.

Mount Edziza consists of several types of volcanic rocks and at least six geological formations that formed during six distinct stages of volcanic activity. The first stage 1.1 million years ago produced basalt flows and a series of rhyolite and trachyte domes. Basalt flows and smaller amounts of trachyte, tristanite, trachybasalt, benmoreite and mugearite produced during the second stage about 1 million years ago comprise Ice Peak, a glacially eroded stratovolcano forming the south peak of Mount Edziza. The third and fourth stages 0.9 million years ago created basalt ridges and the central trachyte stratovolcano of Mount Edziza, respectively. Thick trachyte flows were issued during the fifth stage 0.3 million years ago, most of which have since eroded away. The sixth stage began in the last 20,000 years with the eruption of cinder cones, basalt flows and minor trachyte ejecta. Renewed volcanism could block local streams with lava flows, disrupt air traffic with volcanic ash and produce floods or lahars from melting glacial ice.

Indigenous peoples have lived adjacent to Mount Edziza for thousands of years and it is a sacred mountain to the Tahltan people who historically used volcanic glass from it to make tools and weaponry. Mineral exploration just southeast of Mount Edziza had commenced by the 1950s where gold, silver and other metals were discovered. This mineral exploration was conducted by several mining companies into the early 1990s. Mount Edziza and the surrounding area was made into a large provincial park in the early 1970s to showcase the volcanic landscape. The mountain and provincial park can only be accessed by aircraft or by a network of footpaths from surrounding roads.

Name and etymology

[edit]The mountain was labelled Edziza Peak on Geological Survey of Canada maps as early as 1926. This name for the mountain was adopted by the Geographical Names Board of Canada on September 24, 1945, as identified on the 1926 Geological Survey of Canada map sheet 309A. Edziza Mountain appeared in the 1930 BC Gazetteer, in which the name was erroneously spelled Edzia. On December 3, 1974, the form of name was changed from Edziza Peak to Mount Edziza in accordance with a 1927 British Columbia Land Surveyors report, two world aeronautical charts published in 1950, and three British Columbia maps published in 1931, 1933 and 1943. The form of the name was also changed to reflect entrenched local usage and in conformation with Mount Edziza Provincial Park, which was established in 1972.[2] To the local Tahltan people, Mount Edziza is called Tenh Dẕetle, which translates to 'Ice Mountain'.[2][3]

A number of explanations have been made regarding the origin of the name Edziza. A 1927 report by J. Davidson of the British Columbia Land Surveyors claims that Edziza means 'sand' in the Tahltan language, referring to the deep volcanic ash deposits or pumice-like sand covering large portions of the Big Raven Plateau around Mount Edziza. According to David Stevenson of University of Victoria's Anthropology Department, 'sand' or 'dust' is instead translated as kutlves in Tahltan. An explanation listed in the BC Parks brochure is that Edziza means 'cinders' in the Tahltan language. Another explanation proposed by Canadian volcanologist Jack Souther is that Edziza is a corruption of Edzerza, the name of a local Tahltan family. Obsolete spellings of Edziza include Eddziza, Eddiza, Edidza, Edzia and Etseza.[2]

Geography and geomorphology

[edit]Location and climate

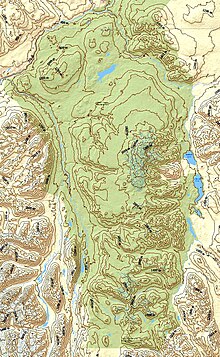

[edit]Mount Edziza rises from within the middle of the Big Raven Plateau, a barren plateau in Cassiar Land District bounded on the west by Mess Valley, on the north by Klastline Valley, on the east by Kakiddi Valley and on the south by Chakima and Walkout valleys.[2][5][11] It lies at the northern end of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex which also includes the smaller Arctic Lake and Kitsu plateaus to the south.[12] This complex of shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes, lava domes, calderas and cinder cones forms a broad, intermontane plateau at the eastern edge of the Tahltan Highland, a southeast-trending upland area extending along the western side of the Stikine Plateau.[13][14]

Mount Edziza is in the Southern Boreal Plateau Ecosection which consists of several upland summits, wide river valleys and deeply incised plateaus.[15] It is one of seven ecosections comprising the Boreal Mountains and Plateaus Ecoregion, a large ecological region of northwestern British Columbia encompassing high plateaus and rugged mountains with intervening lowlands.[16] Boreal forests of black and white spruce occur in the lowlands and valley bottoms of this ecoregion whereas birch, spruce and willow form forests on the mid-slopes. Extensive alpine altai fescue covers the upper slopes, but barren rock is abundant at higher elevations.[17]

The region is characterized by warm summers and cold, snowy winters; temperatures are warmest in mid-summer during the day when they may hit the 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) range. However, temperatures can drop below freezing during summer nights, making snow or freezing rain a possibility at any time of the year.[4] The closest weather stations to Mount Edziza are located at Telegraph Creek and Dease Lake, which lie about 40 kilometres (25 miles) to the northwest and 85 kilometres (53 miles) to the northeast, respectively.[18]

Glaciation

[edit]

Mount Edziza is covered with snow year-round, containing a 15-kilometre-long (9.3-mile) and 9-kilometre-wide (5.6-mile) ice cap which covers an area of 70 square kilometres (27 square miles).[4][19][20] Several small outlet glaciers extending down to elevations of 1,700 to 2,000 metres (5,600 to 6,600 feet) drain the ice cap. Outlet glaciers on the western side of the ice cap spread in broad lobes onto the Big Raven Plateau while distributary glaciers on the eastern side drape down steep slopes to form discontinuous icefalls.[19][20] The Mount Edziza glacier complex is the only one worthy of note on the Stikine Plateau.[21]

Four outlet glaciers of the ice cap are named, and all have names of Tahltan origin. Idiji Glacier descends from the eastern side of the ice cap near the head of Tennaya Creek.[5] At the head of Tenchen Creek is Tenchen Glacier, a debris-covered glacier on the eastern side of the ice cap.[5][22] Tencho Glacier at the southern end of the ice cap is the largest outlet glacier.[5][23] At the head of Tennaya Creek on the eastern side of the ice cap is Tennaya Glacier.[5][24]

As a part of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex, Mount Edziza was covered by a regional ice sheet during the Pleistocene which receded and advanced periodically until about 11,000 years ago when deglaciation was essentially complete in a steadily warming climate.[25][26] This warming trend ceased about 2,600 years ago, causing glaciers to advance from Mount Edziza and elsewhere along the volcanic complex as a part of the neoglaciation. The present trend towards a more moderate climate put an end to the neoglacial period in the 19th century. This has resulted in rapid glacial recession throughout the Mount Edziza volcanic complex. This rapid glacial recession is apparent from the lack of vegetation on the barren, rocky ground between the glaciers and their trim lines which are up to 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) apart.[27]

Structure

[edit]Mount Edziza has an elevation of 2,786 metres (9,140 feet), making it the highest point of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex.[1][13] It has been considered by some to be the highest or tallest volcano in Canada, but others have given higher elevations of 2,860 and 3,160 metres (9,380 and 10,370 feet) for the Silverthrone volcanic complex in southwestern British Columbia.[28][29][30][31] The nearly flat summit of Mount Edziza contains a circular ridge that surrounds an ice-filled, 2-kilometre-in diameter (1.2-mile) crater.[32][33] This ridge is partially exposed above the ice cap as a discontinuous series of spires and serrated nunataks. Spires forming the southern end of the ridge are the highest and consist of greenish grey, sparsely porphyritic[a] trachyte. They comprise well-formed, small diameter rock columns that rise nearly vertically more than 90 metres (300 feet) above the ice cap. Nunataks elsewhere on the summit ridge are more subdued, consisting of pyroclastic debris that has been glacially reworked.[35] The eastern side of the ridge has been breached by active cirques where remnants of several lava lakes are exposed inside the crater.[36] Formation of the summit crater was likely caused by a violent eruption at the zenith of the mountain's growth. Prior to its formation, the summit of the mountain was at least 610 metres (2,000 feet) higher than it is today, having possibly risen as a narrower summit cone.[37]

The central, 2,786-metre-high (9,140-foot) edifice of Mount Edziza is a nearly symmetrical stratovolcano, its symmetry having been broken by several steep-sided lava domes.[1][35] Its eastern flank has been eroded by a narrow cirque which is bounded by near-vertical headwalls that breach the eastern summit crater rim.[38] A system of radial meltwater channels has moderately eroded the upper flanks and summit crater rim elsewhere.[38] Lesser modification by erosion has taken place on the southern and northwestern flanks of the stratovolcano.[35] Along the north side of Tenchen Valley on the eastern flank of the stratovolcano are 850-metre-high (2,790-foot) cliffs exposing explosion breccias, trachyte lavas and landslide or lahar deposits.[39] Although Mount Edziza is surrounded by relatively flat terrain of the Big Raven Plateau to the north, west and south, the terrain east of the mountain is characterized by a series of ridges with intervening valleys. Among these ridges are Idiji Ridge and Sorcery Ridge which are the namesakes of Idiji Glacier and Sorcery Creek.[7]

About 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) south of the summit is Ice Peak, the south peak of Mount Edziza.[40][41] This prominent pyramid-shaped horn has an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,200 feet) and is the glacially eroded remains of an older stratovolcano whose northern flank is buried under the younger edifice of Mount Edziza.[32][41][42] The southern and western flanks are approximal to those of the original stratovolcano whereas the eastern flank has been almost completely destroyed by headward erosion of glacial valleys.[38] At its climax, the stratovolcano had a symmetrical profile and contained a small crater at its summit; the current peak is an erosional remnant etched from the eastern crater rim.[32][43]

Subfeatures

[edit]High on the eastern rim of Ice Peak are two glaciated volcanic cones called Icefall Cone and Ridge Cone, both with elevations of about 2,285 metres (7,497 feet).[44] Punch Cone on the western flank of Ice Peak protrudes through Mount Edziza's ice cap whereas Koosick Bluff and Ornostay Bluff, also on the western flank of Ice Peak, extend westward onto the surrounding Big Raven Plateau.[7][45] The northeastern side of Mount Edziza contains The Pyramid, a pyramid-shaped lava dome 2,199 metres (7,215 feet) in elevation.[46][47] Pillow Ridge on the northern side of Mount Edziza has an elevation of 2,400 metres (7,900 feet) while Tsekone Ridge northwest of Mount Edziza has an elevation of 1,920 metres (6,300 feet).[5][47][48] High on the western side of Mount Edziza is Triangle Dome, an elliptical lava dome 2,680 metres (8,790 feet) in elevation. Glacier Dome reaches an elevation of 2,225 metres (7,300 feet) on Mount Edziza's lower northeastern flank.[47][49]

A circular lava dome on the southeastern crater rim of Mount Edziza called Nanook Dome has an elevation of 2,710 metres (8,890 feet).[50][47] Sphinx Dome, 2,380 metres (7,810 feet) in elevation, is a partially buried lava dome on the northeastern flank of Mount Edziza.[47][51] Remnants of a volcanic pile called Pharaoh Dome occur along the eastern flank of Mount Edziza.[52] They lie at an elevation of 2,200 metres (7,200 feet) between Tennaya Creek and Cartoona Ridge.[47][52] Cinder Cliff is a 210-metre-high (690-foot) barrier of volcanic rocks on the eastern side of Mount Edziza at an elevation of 1,800 metres (5,900 feet) in the north fork of Tenchen Creek.[47][53] The Neck, 1,830 metres (6,000 feet) in elevation, is a circular volcanic plug on the southeastern flank of Ice Peak.[47][54]

The Snowshoe Lava Field on the west flank of lce Peak contains at least 12 volcanic cones, a handful of which are named.[55] Tennena Cone is a symmetrical volcanic cone high on the west side of Ice Peak.[56][57] It has an elevation of 2,350 metres (7,710 feet) and is almost completely surrounded by ice.[47][57] Cocoa Crater is the largest cone in the Snowshoe Lava Field and is 2,117 metres (6,946 feet) in elevation.[47][58] To the southeast is Coffee Crater which has an elevation of 2,000 metres (6,600 feet).[47][59] Keda Cone, 1,980 metres (6,500 feet) in elevation, lies just south of Coffee Crater on the south side of upper Taweh Creek.[47][60] A saucer-shaped mound of lava called The Saucer is 1,920 metres (6,300 feet) in elevation and has a diameter of about 0.5 square kilometres (0.19 square miles).[47][61]

The Desolation Lava Field contains at least 10 cinder cones, most of which are clustered near the northern trim line of Mount Edziza's ice cap.[62] Sleet Cone and Storm Cone are rounded, mostly soil-covered, conical mounds that reach elevations of 1,783 metres (5,850 feet) and 2,135 metres (7,005 feet), respectively.[63] North of Storm Cone are the Triplex Cones, a group of three eroded circular mounds reaching an elevation of 1,785 metres (5,856 feet). Twin Cone, 1,430 metres (4,690 feet) in elevation, is a pyroclastic cone whose southeastern side has been breached.[47][64] Moraine Cone has an elevation of nearly 2,135 metres (7,005 feet) and has been nearly destroyed by alpine glaciation.[65] The northeastern side of Mount Edziza contains Williams Cone, a prominent cinder cone 2,100 metres (6,900 feet) in elevation.[47][66] Eve Cone, 1,740 metres (5,710 feet) in elevation, is a symmetrical cone between Buckley Lake and Mount Edziza.[47][67][68][68] The northernmost cinder cone in the Desolation Lava Field is Sidas Cone which consists of two symmetrical halves and reaches an elevation of 1,540 metres (5,050 feet).[47][55][69]

Drainage

[edit]

Mount Edziza is drained on all sides by streams within the Stikine River watershed.[5][38] Elwyn Creek is a westward-flowing stream originating from the northwestern flank of Mount Edziza.[5][70] It contains one named tributary, Kadeya Creek, which flows northwest from Mount Edziza.[5][71] Sezill Creek is a westward-flowing stream originating from the western flank of Mount Edziza.[5][72] It is a tributary of Taweh Creek which flows northwest from just south of Mount Edziza.[5][73] Elwyn Creek and Taweh Creek are tributaries of Mess Creek which flows northwestward into the Stikine River.[5][74]

Tsecha Creek is a northeast-flowing stream originating from the northern flank of Mount Edziza.[5] Nido Creek flows northeastward from the eastern side of Mount Edziza into Nuttlude Lake.[5][75] Flowing from the eastern flank of Mount Edziza just southeast of The Pyramid is Tenchen Creek.[5] Shaman Creek flows east and north into Kakiddi Lake from the southern flank of Mount Edziza.[5][76] Tennaya Creek flows northeastward from the eastern side of Mount Edziza into Nuttlude Lake.[5][77] All five streams are tributaries of Kakiddi Creek, a north-flowing tributary of the Klastline River which flows north into the Stikine River.[5][78]

Geology

[edit]Background

[edit]Mount Edziza is part of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, a broad area of shield volcanoes, lava domes, cinder cones and stratovolcanoes extending from northwestern British Columbia northwards through Yukon into easternmost Alaska.[79] The dominant rocks comprising these volcanoes are alkali basalts and hawaiites, but nephelinite, basanite and peralkaline[b] phonolite, trachyte and comendite are locally abundant. These rocks were deposited by volcanic eruptions from 20 million years ago to as recently as a few hundred years ago. The cause of volcanic activity in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province is thought to be due to rifting of the North American Cordillera driven by changes in relative plate motion between the North American and Pacific plates.[81]

Composition

[edit]

A wide variety of volcanic rocks comprise Mount Edziza, the main mafic[c] rock being basalt which comprises lava flows, cinder cones and ash beds on the flanks of the mountain.[1][83] Basalt at Mount Edziza is in the form of alkali basalt and hawaiite; the latter is thought to be the product of partial fractional crystallization[d] in subterranean magma chambers.[85][86] Volcanic rocks of intermediate composition such as trachybasalt, tristanite, mugearite and benmoreite are restricted to Ice Peak where they form the upper part of this subsidiary peak.[87] Ice Peak is the only location where mugearites and benmoreites are found in the Mount Edziza volcanic complex.[6] Felsic[e] volcanic rocks such as trachyte and rhyolite form the central stratovolcano of Mount Edziza, the upper part of Ice Peak and several lava domes and flows, as well as pyroclastic rocks.[88]

Stratigraphy

[edit]Mount Edziza is subdivided into at least six geological formations, each the product of a distinct stage of volcanic activity.[89] The oldest geological formation is the Pyramid Formation which formed during a period of volcanic activity 1.1 million years ago.[90] Another period of volcanic activity about 1 million years ago deposited the Ice Peak Formation on the southern part of the Pyramid Formation.[91] The Pillow Ridge and Edziza formations were formed by two periods of volcanic activity 0.9 million years ago, both of which overlie the Ice Peak Formation.[92] A period of volcanic activity 0.3 million years ago deposited the Kakiddi Formation which also overlies the Ice Peak Formation.[93] The youngest geological formation comprising Mount Edziza is the Big Raven Formation which was formed by a period of volcanic activity in the last 20,000 years.[90]

Pyramid Formation

[edit]The Pyramid Formation is exposed along the deeply eroded eastern flank of Mount Edziza where rhyolite and trachyte flows, domes and pyroclastic rocks of this formation comprise ridges and prominent cliffs. A basaltic lava flow sequence up to 65 metres (213 feet) thick overlies the basal trachytic surge deposit of the Pyramid Formation; it is included as a part of this formation due to it being coeval with the early stages of Pyramid felsic volcanism.[94] Potassium–argon dating of the Pyramid Formation has yielded ages of 1.2 ± 0.4 million years and 1.2 ± 0.03 million years from comenditic glass, as well as 0.94 ± 0.12 million years and 0.94 ± 0.05 million years from trachyte.[95]

The Pyramid Formation includes Sphinx Dome, Pharaoh Dome and The Pyramid which were the main sources of the rhyolites and trachytes of this geological formation.[94] The Pyramid is a prominent trachyte dome whose structure has not been greatly modified by erosion, nor has it been buried under younger lavas.[96] In contrast, much of the southern edge of Sphinx Dome has been destroyed by headward erosion of Cook Creek; the western half of this rhyolite dome is also buried under trachyte of the Edziza Formation.[51] From Cartoona Ridge north to Tennaya Creek are isolated remnants of Pharaoh Dome, the main mass of which comprises flow-layered rhyolite and is buried under basalt of the Ice Peak Formation.[97]

Ice Peak Formation

[edit]The Ice Peak Formation consists of lava and pyroclastic rocks that originated mainly from Ice Peak about 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) south of the summit of Mount Edziza.[98] Two stratigraphic units comprise this once symmetrical stratovolcano, both of which are lithologically distinct.[40] The lower stratigraphic unit, which forms much of the volcanic pile, is an assemblage of mostly thin basalt flows. Lavas of intermediate composition such as tristanite, trachybasalt and mugearite are very limited in extent.[99] The upper stratigraphic unit is a highly varied succession of lavas and pyroclastic rocks forming the high, central edifice of Ice Peak.[98] It consists of basalt, trachyte and a variety of intermediate rocks such as tristanite, trachybasalt, benmoreite and mugearite.[8]

The Ice Peak Formation also includes the Koosick and Ornostay bluffs, both of which are thick lobes of trachyte that originated under the summit ice cap. Both bluffs are similar in geomorphology and composition, consisting of several lava flows up to 75 metres (246 feet) thick.[100][101] The Neck, which forms a prominent 215-metre-high (705-foot) buttress on Sorcery Ridge, is also part of the Ice Peak Formation. Potassium–argon dating of pantelleritic trachyte from the Ice Peak Formation has yielded ages of 1.6 ± 0.2 million years, 1.5 ± 0.4 million years and 1.5 ± 0.1 million years.[54] These dates being older than those of the Pyramid Formation may be due to excess argon in the Ice Peak Formation and are therefore considered unreliable.[102][103]

Ice Peak Formation basalt flows on the northwestern flank of Mount Edziza are interbedded with diamictites recording a regional glaciation that occurred during the Early Pleistocene.[104] The lowermost basalt flow contains basal pillows, directly overlies hyaloclastites and is brecciated and deformed, suggesting it may have been extruded onto a glacier or an ice sheet.[43][104] Its extrusion onto glacial ice is also evident due to the lack of fluvial and lacustrine sediments at the base of the basalt flow which suggests it did not extrude into lakes or streams.[104] The steep sides and unusually large thicknesses of the trachyte flows comprising Koosick and Ornostay bluffs is attributed to them having been extruded through glacial ice.[105]

Pillow Ridge Formation

[edit]The Pillow Ridge Formation is restricted to Pillow Ridge and Tsekone Ridge on Mount Edziza's northwestern flank, both of which are glaciovolcanic in origin.[48][106] Pillow Ridge is a nearly 4-kilometre-long (2.5-mile), northwesterly-trending ridge of basaltic pillow lava, pillow breccia, tuff breccia and dikes.[48] Its upper surface is sparsely covered by trachyte of the Edziza Formation while the western edge of the ridge overlaps with a large flow of Edziza trachyte.[107] Tsekone Ridge is an isolated volcanic pile adjacent to Pillow Ridge consisting of basaltic pillow lava and tuff breccia that has been cut by vertical north-trending feeder dikes.[108] This ridge is elliptical in structure, containing a nearly 2-kilometre-long (1.2-mile), north–south trending axis.[48] Nearly surrounding Tsekone Ridge are trachyte flows of the Edziza Formation which is slightly younger than the Pillow Ridge Formation.[109]

Fission track dating of apatite from partially fused granitic xenoliths[f] in contaminated Pillow Ridge Formation basalt has yielded ages of 0.9 ± 0.3 million years and 0.8 ± 0.25 million years.[111] In contrast, potassium–argon dating has yielded an anomalously old age of 5.9 ± 0.9 million years which is inconsistent with the ages of the underlying and overlying formations. This date being much older than the fission track dates most likely results from contamination and introduction of excess argon from the partially fused granitic and gneissic xenoliths in Pillow Ridge Formation basalt.[112]

Edziza Formation

[edit]

The Edziza Formation consists mainly of trachyte that straddles the pantelleritic trachyte and comenditic trachyte boundary.[113] It includes the central stratovolcano of Mount Edziza, as well as several satellitic features on its summit and flanks.[114] Inside the summit crater of the stratovolcano is a succession of at least four lava lakes exposed in the breached eastern crater rim.[36][115] They are represented by at least four cooling units, the lower two of which are about 30 metres (98 feet) thick.[115] The two upper cooling units reach thicknesses of about 90 metres (300 feet) and may have originated from Nanook Dome, the largest of three lava domes consisting of Edziza Formation trachyte.[116] Nanook Dome is about 750 metres (2,460 feet) in diameter whose structure appears to be nearly identical to its original form.[117] The other two Edziza Formation trachyte domes, Glacier Dome and Triangle Dome, are elliptical in structure and contain concentric flow layering.[49] Potassium–argon dating of pantelleritic trachyte or comenditic trachyte from the Edziza Formation has yielded an age of 0.9 ± 0.3 million years.[113][118]

Kakiddi Formation

[edit]The Kakiddi Formation consists of the remains of thick trachyte flows and associated pyroclastic rocks. They are lithologically and geomorphologically similar to Edziza Formation trachytes, but occur south of the central stratovolcano of Mount Edziza. The remains of a nearly 1-kilometre-wide (0.62-mile), rubble-covered trachyte flow are present on the eastern flank of Ice Peak in Sorcery Valley and in the south fork of Tennaya Valley where it is divided into two tributary branches. In Kakiddi Valley, the lava flow appears to have spread out to form a once continuous, terminal lobe at least 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) wide. Remnants of this terminal lobe are present in the form of isolated outcrops adjacent to Kakiddi Lake and Nuttlude Lake.[119] The source of this Kakiddi flow remains unknown, but the tributary branch that descended Tennaya Valley probably originated from a vent near the summit of Ice Peak that is now covered by glaciers.[120] Another plausible source is Nanook Dome on the southeastern crater rim of Mount Edziza.[121] A relatively small trachyte flow descended from a vent on the western flank of Ice Peak and spread onto the Big Raven Plateau.[122] Potassium–argon dating of the Kakiddi Formation has yielded ages of 0.31 ± 0.07 million years from mugearite, as well as 0.30 ± 0.02 million years, 0.29 ± 0.02 million years and 0.28 ± 0.02 million years from trachyte.[123]

Big Raven Formation

[edit]

The Big Raven Formation includes the Desolation Lava Field, the Snowshoe Lava Field, Icefall Cone, Ridge Cone, Cinder Cliff and the Sheep Track Member.[124] All of these features consist of alkali basalt and hawaiite with the exception of the Sheep Track Member which comprises a small volume of trachyte pumice.[85] Some of the lava flows comprising the Desolation Lava Field issued from vents adjacent to the northern trim line of the summit ice cap where meltwater interacted with the erupting lava to form tuff rings. These tuff rings, composed of quenched breccia, later transitioned into normal subaerial cinder cones as the progressing eruptions displaced ice and meltwater.[56] The Snowshoe Lava Field contains subglacial and subaerial cones, as well as transitional cones which consist of both subaqueous and subaerial ejecta.[125]

Eruptions on the heavily eroded eastern flank of Mount Edziza created Icefall Cone, Ridge Cone and Cinder Cliff which comprise a separate volcanic zone called the east slope centres.[126] The Sheep Track Member is the product of an explosive eruption that originated from the southwestern flank of Ice Peak.[127] It was deposited on all lava flows and cinder cones in the Snowshoe Lava Field with the exception of The Saucer which likely postdates the Sheep Track eruption. The source of the Sheep Track pumice is unknown, but it probably originated from a vent hidden under Tencho Glacier.[128] Holocene in age, the Big Raven Formation has yielded dates of 6520 BCE ± 200 years, 750 BCE ± 100 years, 610 CE ± 150 years and 950 CE ± 6000 years.[129]

Basement

[edit]Underlying the aforementioned geological formations is the Tenchen Member of the Nido Formation, one of many stratigraphic units forming the Big Raven Plateau. Basalt flows and pyroclastic rocks of this Pliocene geological member are exposed north of Raspberry Pass on the eastern and western flanks of Mount Edziza.[7][130] Much of the Tenchen Member as well as the southern edge of the Ice Peak volcanic pile are underlain by the Armadillo Formation which consists of Miocene comendite, trachyte and alkali basalt.[7][131] Most of Mount Edziza is also underlain by Miocene basalt flows of the Raspberry Formation which form the base of prominent escarpments east and west of the mountain.[7][132] These geological formations are underlain by the Stikinia terrane, a Paleozoic and Mesozoic suite of volcanic and sedimentary rocks that accreted to the continental margin of North America during the Jurassic.[133][134]

Hazards and monitoring

[edit]Natural Resources Canada considers Mount Edziza a high threat volcano because it has had the highest eruption rate in Canada throughout the Holocene. However, its extremely remote location makes it less hazardous than Mount Garibaldi, Mount Price, Mount Cayley and Mount Meager in southwestern British Columbia.[135] The hazard rating of Mount Edziza is similar to that of Mount Churchill in the U.S. state of Alaska which deposited the White River Ash across northwestern Canada in the last 2,000 years.[136][137] Lava flows are a potential hazard at Mount Edziza as they have formerly dammed local streams.[138] Another potential hazard is the ignition of wildfires by eruptions since the surrounding area contains vegetation.[4][138] An eruption under the ice cap could produce floods or lahars that may flow into the Stikine or Iskut rivers, potentially destroying salmon runs and threatening river bank villages.[139][140]

Mount Edziza trachyte and rhyolite have silica-rich compositions that are comparable to those associated with the most powerful eruptions around the world; parts of northwestern Canada could be affected by an ash column if an explosive eruption were to happen from the volcano.[138] Ash columns can drift for thousands of kilometres downwind and often become increasingly spread out over a larger area with increasing distance from an erupting vent.[141] Mount Edziza lies under a major air route from Vancouver, British Columbia to Whitehorse, Yukon, suggesting the volcano poses a potential threat to air traffic.[139] Volcanic ash reduces visibility and can cause jet engine failure, as well as damage to other aircraft systems.[142]

Like other volcanoes in Canada, Mount Edziza is not monitored closely enough by the Geological Survey of Canada to ascertain its activity level. The Canadian National Seismograph Network has been established to monitor earthquakes throughout Canada, but it is too far away to provide an accurate indication of activity under the mountain. It may sense an increase in seismic activity if Mount Edziza becomes highly restless, but this may only provide a warning for a large eruption; the system might detect activity only once the volcano has started erupting.[143] If Mount Edziza were to erupt, mechanisms exist to orchestrate relief efforts. The Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan was created to outline the notification procedure of some of the main agencies that would respond to an erupting volcano in Canada, an eruption close to the Canada–United States border or any eruption that would affect Canada.[144]

Human history

[edit]Indigenous peoples

[edit]Mount Edziza lies within the traditional territory of the Tahltan people which covers an area of more than 93,500 square kilometres (36,100 square miles).[145] Historically, Mount Edziza and other volcanoes of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex were sources of obsidian for the Tahltan people.[146] This volcanic glass was used in the manufacturing of projectile points and cutting blades which were widely traded throughout the Pacific Northwest.[4] Artifacts made of Edziza obsidian have been recovered from archaeological sites over an area of more than 2,200,000 km2 (850,000 sq mi) across Alaska, Alberta, Yukon and the British Columbia Coast, making it the most widely distributed obsidian in western North America. The Hidden Falls archaeological site in Alaska has yielded a hydration date of 10,000 years for Edziza obsidian, suggesting the area was being exploited as an obsidian source soon after ice sheets of the Last Glacial Period retreated.[147]

Two obsidian flows of the Pyramid Formation occur on The Pyramid and are exposed as two outcrops; they were quarried as evidenced by the occurrence of this obsidian in at least five archaeological sites outside of Tahltan territory. The Ice Peak Formation contains two obsidian flows on Sorcery Ridge that were also exploited as an obsidian source.[148] Sorcery Ridge obsidian occurs in at least two archaeological sites outside of Tahltan territory.[149]

In or before 1974, two Tahltan men named Johnny Edzerza and Hank Williams were killed in an avalanche while they were crossing the mountain. Edzerza was buried on Mount Edziza, but his surname was erroneously spelled "Edzertza" on his grave marker.[2] Williams Cone on the northeastern side of Mount Edziza was named in honour of Hank Williams while Eve Cone between Mount Edziza and Buckley Lake was named in honour of Johnny Edzerza's wife, Eve Brown Edzerza.[66][68]

Mount Edziza continues to be an important cultural resource for the Tahltan people. In 2021, Chad Norman Day, president of the Tahltan Central Government, said "Mount Edziza and the surrounding area has always been sacred to the Tahltan Nation. The obsidian from this portion of our territory provided us with weaponry, tools and trading goods that ensured our Tahltan people could thrive for thousands of years."[150]

Mineral exploration

[edit]

Just southeast of Mount Edziza was an area once known as the Spectrum property, a block of mineral claims that covered quartz, pyrite and chalcopyrite mineralization in fractured sedimentary and volcanic rocks of Late Triassic age.[151][152] Commodities on the property included copper, gold, lead, silver and zinc.[152] Mineral exploration on the Spectrum property began as early as 1957 when Torbit Silver Mines performed surface work on the gold-bearing Hawk vein. This was followed by drilling of the Hawk vein by Shawnigan Mining and Smelting in 1967. Exploration by Mitsui Mining and Smelting in 1970 involved geophysical and geochemical surveying. From 1971 to 1973, Imperial Oil conducted geophysical, geological and geochemical surveying, as well as 463 metres (1,519 feet) of drilling in four holes.[151]

Between 1976 and 1981, geochemical and geological surveys were conducted on the Spectrum property by Consolidated Silver Ridge Mines and Newhawk Mines. Consolidated Silver Ridge Mines built an airstrip and carried out 3,232 metres (10,604 feet) of drilling in 28 holes during this time. Newhawk Mines constructed an access road and 313 metres (1,027 feet) of underground development on the Hawk vein. Further geochemical and geological surveying was performed by Moongold Resources from 1987 to 1989. Mineral exploration conducted by Columbia Gold Mines from 1990 to 1992 consisted of rock sampling, trenching and 7,066 metres (23,182 feet) of drilling in 50 holes.[151]

Protected areas

[edit]Mount Edziza and the surrounding area was designated as a provincial park in 1972 to showcase the volcanic landscape; a 101,171-hectare (250,000-acre) recreation area surrounding the 132,000-hectare (330,000-acre) park was also established in 1972.[4][153][154] In 1989, Mount Edziza Provincial Park roughly doubled in size when 96,770 hectares (239,100 acres) was annexed from the Mount Edziza Recreation Area.[154] With this annexation, the recreation area was greatly reduced in size to around 4,000 hectares (9,900 acres).[153] This remnant of the recreation area was east of Mount Edziza until 2003 when it was disestablished.[5][153] Mount Edziza Provincial Park now covers an area of 266,180 hectares (657,700 acres), making it one of the largest provincial parks in British Columbia.[155]

In 2021, an approximately 3,528-hectare (8,720-acre) conservation area called the Mount Edziza Conservancy was established east of Mount Edziza along the eastern border of Mount Edziza Provincial Park.[156] It was established in collaboration with Skeena Resources, BC Parks, the Tahltan Central Government and the Nature Conservancy of Canada after Skeena Resources returned their mineral tenures on the Spectrum property.[157] The name of this conservation area was changed to the Tenh Dẕetle Conservancy in 2022 to better reflect the culture, history and tradition of the Tahltan First Nation.[3][156]

Accessibility

[edit]Mount Edziza lies in a remote location that is accessible only during summer and early autumn.[158] There is no established road access to the mountain, although the Stewart–Cassiar Highway to the east and the Telegraph Creek Road to the northwest both extend within 40 kilometres (25 miles) of Mount Edziza.[159][160] Extending from these roads are horse trails that provide access to the mountain.[161] From Telegraph Creek, the Buckley Lake Trail extends about 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) southeast along Mess Creek and Three Mile Lake. It then traverses about 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) northeast along Dagaichess Creek and Stinking Lake to the northeastern end of Buckley Lake where it meets with the Klastline River Trail and the Buckley Lake to Mowdade Lake Route.[29]

To the east, the roughly 50-kilometre-long (31-mile) Klastline River Trail begins at the community of Iskut on the Stewart–Cassiar Highway.[162] It extends northwest and west along the Klastline River for much of its length.[159] The trail enters Mount Edziza Provincial Park at about 25 kilometres (16 miles) where Kakiddi Creek drains into the Klastline River.[162] After entering Mount Edziza Provincial Park, the Klastline River Trail traverses northwest along the Klastline River for about 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) and then crosses the river north of Mount Edziza.[159] From there, the Klastline River Trail traverses west for about 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) to the northeastern end of Buckley Lake where it meets with the Buckley Lake Trail and the Buckley Lake to Mowdade Lake Route.[29]

The Buckley Lake to Mowdade Lake Route traverses south from Buckley Lake along Buckley Creek and gradually climbs onto the Big Raven Plateau where Eve Cone, Sidas Cone and Tsekone Ridge are visible along the route.[5][29][163] Most of the Buckley Lake to Mowdade Lake Route is marked by a series of rock cairns from Tsekone Ridge onwards. The distance between Buckley Lake and Mowdade Lake is about 70 kilometres (43 miles), but the hiking length between these two lakes varies depending on the route taken; it can take a minimum of 7 days to hike the Buckley Lake to Mowdade Lake Route. The weather can change extremely fast along this hiking trail.[163]

Mount Edziza can also be accessed by float plane or helicopter, both of which are available for charter at the communities of Iskut and Dease Lake.[158][161] Kakiddi Lake, Nuttlude Lake, Mowdade Lake, Mowchilla Lake and Buckley Lake are large enough to be used by float-equipped aircraft.[4][161] Landing on the latter two lakes with a private aircraft requires a letter of authorization from the BC Parks Stikine Senior Park Ranger.[4]

See also

[edit]- Volcanism of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex

- List of the most prominent summits of Canada

- List of Northern Cordilleran volcanoes

- List of volcanoes in Canada

Notes

[edit]- ^ Porphyritic pertains to the resemblance of porphyry which are magmatic rocks consisting of large crystals in a fine-grained matrix.[34]

- ^ Peralkaline rocks are magmatic rocks that have a higher ratio of sodium and potassium to aluminum.[80]

- ^ Mafic pertains to magmatic rocks that are relatively rich in iron and magnesium, relative to silicium.[82]

- ^ Fractional crystallization is the process by which magma cools and separates into various minerals.[84]

- ^ Felsic pertains to magmatic rocks that are enriched with silicon, oxygen, aluminum, sodium and potassium.[82]

- ^ Xenoliths are rock fragments that become enveloped in a larger rock during the latter's development and solidification.[110]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Global Volcanism Program: Edziza, General Information.

- ^ a b c d e f g h BC Geographical Names: Mount Edziza.

- ^ a b c d Government of British Columbia: Conservancy renamed Ice Mountain, reflects Tahltan heritage 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h BC Parks: Mount Edziza Provincial Park.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Department of Energy, Mines and Resources 1989.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 267.

- ^ a b c d e f g Souther 1988.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 150.

- ^ Edwards & Russell 2000, p. 1284.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 213, 226.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Big Raven Plateau.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 32.

- ^ a b Wood & Kienle 1990, p. 124.

- ^ Holland 1976, pp. 49, 50.

- ^ Demarchi 2011, p. 146.

- ^ Demarchi 2011, pp. 143–147.

- ^ Demarchi 2011, p. 143.

- ^ D.R. Piteau and Associates 1988, pp. 3, 4.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 36.

- ^ a b Field 1975, p. 43.

- ^ Denton 1975, p. 663.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Tenchen Glacier.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Tencho Glacier.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Tennaya Glacier.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 18–20, 25.

- ^ Wilson & Kelman 2021, p. 10.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 25.

- ^ Wood & Kienle 1990, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d Mussio 2018, p. 88.

- ^ Cannings & Cannings 2014, p. 178.

- ^ Global Volcanism Program: Silverthrone, General Information.

- ^ a b c Wood & Kienle 1990, p. 125.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 177.

- ^ Imam 2003, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Souther 1992, p. 175.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 125.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 21, 177.

- ^ a b c d Souther 1992, p. 33.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 175, 177.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 145.

- ^ a b BC Geographical Names: Ice Peak.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 32, 33.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 228.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 24, 25, 155.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: The Pyramid.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Global Volcanism Program: Edziza, Synonyms & Subfeatures.

- ^ a b c d Souther 1992, p. 165.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 181.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 21.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 134.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 135.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 26, 226.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 154.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, pp. 27, 214.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 26.

- ^ a b BC Geographical Names: Tennena Cone.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 232.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 214.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Keda Cone.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 233.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 26, 213, 214.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 216, 218, 219.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 219.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 222.

- ^ a b BC Geographical Names: Williams Cone.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 223.

- ^ a b c BC Geographical Names: Eve Cone.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Sidas Cone.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Elwyn Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Kadeya Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Sezill Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Taweh Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Mess Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Nido Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Shaman Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Tennaya Creek.

- ^ BC Geographical Names: Klastline River.

- ^ Edwards & Russell 2000, pp. 1280, 1281, 1283, 1284.

- ^ Imam 2003, p. 253.

- ^ Edwards & Russell 2000, p. 1280.

- ^ a b Pinti 2011, p. 938.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 213, 226, 228.

- ^ Imam 2003, p. 126.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 213.

- ^ Souther & Hickson 1984, p. 79.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 1, 145, 150.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 129, 150, 175, 179, 181.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 2, 246.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, pp. 246, 267.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 145, 246, 267.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 246, 247, 267.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 207, 267.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 129.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 248, 249.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 132.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 135, 136.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, pp. 145, 150.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 147.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 155.

- ^ Lamoreaux et al. 2006.

- ^ Government of Canada: Ice Peak Formation.

- ^ Spooner et al. 1995, p. 2047.

- ^ a b c Spooner et al. 1995, p. 2046.

- ^ Smellie & Edwards 2016, p. 43.

- ^ Lloyd et al. 2006.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 171.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 165, 172.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 21, 250.

- ^ Imam 2003, p. 399.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 28, 250.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 250.

- ^ a b Souther, Armstrong & Harakal 1984, p. 346.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 175, 177, 179, 181.

- ^ a b Souther 1992, p. 185.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 179, 185.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 179.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 248.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 207.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 24.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 21, 24.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 24, 25.

- ^ Souther, Armstrong & Harakal 1984, p. 341.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 26–28, 226, 228.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 229, 231.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 226, 228.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 27, 28.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 237.

- ^ Global Volcanism Program: Edziza, General Information and Eruptive History.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 145, 267.

- ^ Souther 1992, pp. 3, 4, 47.

- ^ Souther 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Edwards & Russell 2000, pp. 1281, 1287.

- ^ Wilson & Kelman 2021, pp. 8, 29, 33.

- ^ Wilson & Kelman 2021, p. 35.

- ^ Natural Resources Canada: Mount Churchill.

- ^ a b c Natural Resources Canada: Mount Edziza.

- ^ a b Natural Resources Canada: Volcanic hazards.

- ^ Edwards 2010.

- ^ United States Geological Survey: Eruption column.

- ^ Neal et al. 2004.

- ^ Natural Resources Canada: Monitoring volcanoes.

- ^ Natural Resources Canada: Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan.

- ^ Markey, Halseth & Manson 2012, p. 242.

- ^ Reiner 2015, pp. 418, 419.

- ^ Millennia Research Ltd. 1998, pp. 44, 46.

- ^ Reiner 2015, pp. 419, 420, 425.

- ^ Reiner 2015, p. 425.

- ^ Government of British Columbia: Tahltan land to be protected in partnership with conservation organizations, industry and Province.

- ^ a b c Wojdak 1993, p. 3.

- ^ a b Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources.

- ^ a b c BC Parks: Mount Edziza Recreational Area.

- ^ a b BC Geographical Names: Mount Edziza Park.

- ^ Global Volcanism Program: Edziza, Photo Gallery.

- ^ a b BC Geographical Names: Tenh Dzetle Conservancy.

- ^ Skeena Resources, p. 13.

- ^ a b Reiner 2015, p. 418.

- ^ a b c Mussio 2018, pp. 88, 89.

- ^ Wood & Kienle 1990, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Souther 1992, p. 31.

- ^ a b Mussio 2018, p. 89.

- ^ a b BC Parks: Hiking and Wilderness Camping in Mount Edziza Provincial Park.

Sources

[edit]- "A 502" (Topographic map). Telegraph Creek, Cassiar Land District, British Columbia (3 ed.). 1:250,000. 104 G (in English and French). Department of Energy, Mines and Resources. 1989. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021.

- "Big Raven Plateau". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021.

- Cannings, Richard; Cannings, Sydney (2014). "The Stewart-Cassiar Highway". The New B.C. Roadside Naturalist: A Guide to Nature along B.C. Highways. Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-77100-054-3.

- "Condensed Interim Consolidated Financial Statements" (PDF). Skeena Resources. 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2022.

- "Conservancy renamed Ice Mountain, reflects Tahltan heritage". Government of British Columbia. February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022.

- Demarchi, Dennis A. (2011). An Introduction to the Ecoregions of British Columbia (PDF). Government of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2024.

- Denton, George H. (1975). "Glaciers of the Interior Ranges of British Columbia". Mountain Glaciers of the Northern Hemisphere. Vol. 2. Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. pp. 655–663.

- D.R. Piteau and Associates (1988). Geochemistry and Isotope Hydrogeology of the Mount Edziza and Mess Creek Geothermal Waters, British Columbia (Report). Open File 1732. Geological Survey of Canada. doi:10.4095/130715.

- Edwards, Benjamin R.; Russell, James K. (2000). "Distribution, nature, and origin of Neogene–Quaternary magmatism in the northern Cordilleran volcanic province, Canada". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 112 (8). Geological Society of America: 1280–1295. Bibcode:2000GSAB..112.1280E. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2000)112<1280:dnaoon>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Edwards, B. R. (2010). Hazards associated with alkaline glaciovolcanism at Hoodoo Mountain and Mt. Edziza, western Canada: comparisons to the 2010 Eyjafjallajokull eruption. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2010. Astrophysics Data System. Bibcode:2010AGUFMNH11B1132E.

- "Edziza". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021.

- "Elwyn Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021.

- "Eruption column". United States Geological Survey. July 28, 2015. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023.

- "Eve Cone". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021.

- Field, William O. (1975). "Coast Mountains: Boundary Ranges (Alaska, British Columbia, and Yukon Territory)". Mountain Glaciers of the Northern Hemisphere. Vol. 2. Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. pp. 11–141.

- Holland, Stuart S. (1976). Landforms of British Columbia: A Physiographic Outline (PDF) (Report). Government of British Columbia. ASIN B0006EB676. OCLC 601782234. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 14, 2018.

- "Ice Peak". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021.

- "Ice Peak Formation". Lexicon of Canadian Geologic Units. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on December 12, 2023.

- Imam, Naiyar (2003). Dictionary of Geology and Mineralogy. McGraw–Hill Companies. ISBN 0-07-141044-9.

- "Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan (IVENP)". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009.

- "Kadeya Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024.

- "Keda Cone". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021.

- "Klastline River". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021.

- Lamoreaux, K. A.; Skilling, I. P.; Endress, C.; Edwards, B.; Lloyd, A.; Hungerford, J. (2006). Preliminary Studies of the Emplacement of Trachytic Lava Flows and Domes in an Ice- Contact Environment: Mount Edziza, British Columbia, Canada. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006. Astrophysics Data System. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.V53C1757L.

- Lloyd, A.; Edwards, B.; Edwards, C.; Skilling, I.; Lamoreaux, K. (2006). Preliminary Interpretation of Processes and Products at two Basaltic Glaciovolcanic Ridges: Tsekone and Pillow Ridges, Mount Edziza Volcanic Complex (MEVC), NCVP, British Columbia, Canada. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006. Astrophysics Data System. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.V53C1754L.

- Markey, Sean; Halseth, Greg; Manson, Don (2012). Investing in Place: Economic Renewal in Northern British Columbia. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2293-0.

- "Mess Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021.

- Millennia Research Ltd. (1998). Archaeological Overview Assessment of the Cassiar-Iskut-Stikine LRMP (PDF) (Report). Vol. 1. Government of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2022.

- "MINFILE No. 104B 036". Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- "Monitoring volcanoes". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. February 26, 2009. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008.

- "Mount Churchill". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. March 10, 2009. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009.

- "Mount Edziza". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018.

- "Mount Edziza Park". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018.

- "Mount Edziza Provincial Park". BC Parks. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023.

- "Mount Edziza Provincial Park: Hiking and Wilderness Camping". BC Parks. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022.

- "Mount Edziza Recreation Area". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 7, 2024.

- Mussio, Russell, ed. (2018). Northern BC Backroad Mapbook. Mussio Ventures. ISBN 978-1-926806-87-7.

- Neal, Christina A.; Casadevall, Thomas J.; Miller, Thomas P.; Hendley II, James W.; Stauffer, Peter H. (October 14, 2004). "Volcanic Ash–Danger to Aircraft in the North Pacific". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021.

- "Nido Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 7, 2024.

- Pinti, Daniele (2011). "Mafic and Felsic". Encyclopedia of Astrobiology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11274-4_1893. ISBN 978-3-642-11271-3.

- Reiner, Rudy (2015). "Reassessing the role of Mount Edziza obsidian in northwestern North America". Journal of Archaeological Science. 2. Elsevier: 418, 419, 425. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.04.003.

- "Sezill Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024.

- "Shaman Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024.

- "Sidas Cone". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021.

- "Silverthrone". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on September 17, 2024.

- Smellie, John L.; Edwards, Benjamin R. (2016). Glaciovolcanism on Earth and Mars: Products, Processes and Palaeoenvironmental Significance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03739-7.

- Souther, J. G. (1988). "1623A" (Geologic map). Geology, Mount Edziza Volcanic Complex, British Columbia. 1:50,000. Cartography by M. Sigouin, Geological Survey of Canada. Energy, Mines and Resources Canada. doi:10.4095/133498.

- Souther, J. G. (1992). The Late Cenozoic Mount Edziza Volcanic Complex, British Columbia. Geological Survey of Canada (Report). Memoir 420. Canada Communication Group. doi:10.4095/133497. ISBN 0-660-14407-7.

- Souther, J. G.; Armstrong, R. L.; Harakal, J. (1984). "Chronology of the peralkaline, late Cenozoic Mount Edziza Volcanic Complex, northern British Columbia, Canada". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 95 (3). Geological Society of America: 337–349. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1984)95<337:COTPLC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Souther, J. G.; Hickson, C. J. (1984). "Crystal fractionation of the basalt comendite series of the mount Edziza volcanic complex, British Columbia: Major and trace elements". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 21 (1). Elsevier: 79–106. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(84)90017-9. ISSN 0377-0273.

- Spooner, I. S.; Osborn, G. D.; Barendregt, R. W.; Irving, E. (1995). "A record of Early Pleistocene glaciation on the Mount Edziza Plateau, northwestern British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 32 (12). NRC Research Press: 2046–2056. Bibcode:1995CaJES..32.2046S. doi:10.1139/e95-158. ISSN 0008-4077.

- "Stikine volcanic belt: Mount Edziza". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. April 1, 2009. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009.

- "Tahltan land to be protected in partnership with conservation organizations, industry and Province". Government of British Columbia. 2021. Archived from the original on November 18, 2022.

- "Taweh Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021.

- "Tenchen Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024.

- "Tencho Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 7, 2024.

- "Tennaya Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024.

- "Tennaya Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 7, 2024.

- "Tennena Cone". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021.

- "Tenh Dẕetle Conservancy". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on June 8, 2024.

- "The Pyramid". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021.

- "Volcanic hazards". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. October 10, 2007. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009.

- "Williams Cone". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021.

- Wilson, Alexander M.; Kelman, Melanie C. (2021). Assessing the relative threats from Canadian volcanoes (Report). Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 8790. Natural Resources Canada. doi:10.4095/328950.

- Wojdak, Paul (1993). Evaluation of Mineral Potential for Mount Edziza Recreation Area (PDF) (Report). Government of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2021.

- Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen (1990). Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43811-X.

External links

[edit]- "Skiing the Pacific Ring of Fire and Beyond: Mount Edziza". Amar Andalkar's Ski Mountaineering and Climbing Site.

- "Mount Edziza". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- "Mount Edziza, British Columbia". Peakbagger.com.

- "Edziza Volcano". VolcanoDiscovery.

- "Edziza Volcano". Volcano Live.