East African Community

| Motto: "Ushirikiano wa Afrika Mashariki" | |

| Anthem: "Wimbo wa Jumuiya Afrika Mashariki" | |

An orthographic map projection of the world, highlighting the East African Community's member states (green) | |

| Headquarters | Arusha, Tanzania 3°22′S 36°41′E / 3.367°S 36.683°E |

| Largest city | Kinshasa, DR Congo |

| Official languages | English[1] |

| Lingua franca | Swahili, French[1] |

| Demonym(s) | East African |

| Type | Intergovernmental |

| Partner states | |

| Leaders | |

• Summit Chairperson | |

• Council Chairperson | |

• EACJ President | |

• EALA Speaker | |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly |

| Establishment | |

• First established | 1967 |

• Dissolved | 1977 |

• Re-established | 7 July 2000 |

| Area | |

• Total | 5,449,717[3] km2 (2,104,147 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 3.83 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 343,328,958[3] |

• Density | 63/km2 (163.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | Int$1,027.067 billion[4] |

• Per capita | Int$2,991 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | US$349.774 billion[4] |

• Per capita | US$1,019 |

| HDI (2022) | 0.515 low |

| Drives on | Left (in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda) right (in the rest of the EAC) |

Website www | |

The East African Community (EAC) is an intergovernmental organisation in East Africa. The EAC's membership consists of eight states: Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Federal Republic of Somalia, the Republics of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda, and Tanzania.[5] William Ruto, the president of Kenya, is the current EAC chairman. The organisation was founded in 1967, collapsed in 1977, and was revived on 7 July 2000.[6] The main objective of the EAC is to foster regional economic integration.

In 2008, after negotiations with the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the EAC agreed to an expanded free trade area including the member states of all three organizations. The EAC is an integral part of the African Economic Community.

The EAC is a potential precursor to the establishment of the East African Federation, a proposed federation of its members into a single sovereign state.[7] In 2010, the EAC launched its own common market for goods, labour, and capital within the region, with the goal of creating a common currency and eventually a full political federation.[8] In 2013, a protocol was signed outlining their plans for launching a monetary union within 10 years.[9] In September 2018, a committee was formed to begin the process of drafting a regional constitution.[10]

History

[edit]Formation and re-formation

[edit]

Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda have cooperated with each other since the early 20th century. The East African Currency Board provided a common currency from 1919 to 1966. The customs union between Kenya and Uganda in 1917, which Tanganyika joined in 1927, was followed by the East African High Commission (EAHC) from 1948 to 1961, the East African Common Services Organization (EACSO) from 1961 to 1967, and the EAC[11] from 1967 to 1977. Burundi and Rwanda joined the EAC on 6 July 2009.[12]

Inter-territorial co-operation between the Kenya Colony, the Uganda Protectorate, and the Tanganyika Territory was formalised in 1948 by the EAHC. This provided a customs union, a common external tariff, currency, and postage. It also dealt with common services in transport and communications, research, and education. Following independence, these integrated activities were reconstituted and the EAHC was replaced by the EACSO, which many observers thought would lead to a political federation between the three territories. The new organisation ran into difficulties because of the lack of joint planning and fiscal policy, separate political policies, and Kenya's dominant economic position. In 1967, the EACSO was superseded by the EAC. This body aimed to strengthen the ties between the members through a common market, a common customs tariff, and a range of public services to achieve balanced economic growth within the region.[13]

In 1977, the EAC collapsed. The causes of the collapse included demands by Kenya for more seats than Uganda and Tanzania in decision-making organs,[14] disagreements with Ugandan dictator Idi Amin who demanded that Tanzania as a member state of the EAC should not harbour forces fighting to topple the government of another member state, and the disparate economic systems of socialism in Tanzania and capitalism in Kenya.[15] The three member states lost over sixty years of co-operation and the benefits of economies of scale, although some Kenyan government officials celebrated the collapse with champagne.[16]

Presidents Daniel arap Moi of Kenya, Ali Hassan Mwinyi of Tanzania, and Yoweri Kaguta Museveni of Uganda signed the Treaty for East African Co-operation in Kampala on 30 November 1993 and established a Tri-partite Commission for Co-operation.[17] A process of re-integration was embarked on involving tripartite programs of co-operation in political, economic, social and cultural fields, research and technology, defence, security, and legal and judicial affairs.

The EAC was revived on 30 November 1999, when the treaty for its re-establishment was signed. It came into force on 7 July 2000, 23 years after the collapse of the previous community and its organs. A customs union was signed in March 2004, which commenced on 1 January 2005. Kenya, the region's largest exporter, continued to pay duties on goods entering the other four countries on a declining scale until 2010. A common system of tariffs will apply to goods imported from third-party countries.[18] On 30 November 2016 it was declared that the immediate aim would be confederation rather than federation.[19]

South Sudan's accession

[edit]The presidents of Kenya and Rwanda invited the Autonomous Government of Southern Sudan to apply for membership upon the independence of South Sudan in 2011,[20][21] and South Sudan was reportedly an applicant country as of mid-July 2011.[20][22] Analysts suggested that South Sudan's early efforts to integrate infrastructure, including rail links and oil pipelines,[23] with systems in Kenya and Uganda indicated intention on the part of Juba to pivot away from dependence on Sudan and toward the EAC. Reuters considers South Sudan the likeliest candidate for EAC expansion in the short term,[24] and an article in Tanzanian daily The Citizen that reported East African Legislative Assembly Speaker Abdirahin Haithar Abdi said South Sudan was "free to join the EAC" asserted that analysts believe the country will soon become a full member of the regional body.[25]

On 17 September 2011, the Daily Nation quoted a South Sudanese MP as saying that while his government was eager to join the EAC, it would likely delay its membership over concerns that its economy was not sufficiently developed to compete with EAC member states and could become a "dumping ground" for Kenyan, Tanzanian, and Ugandan exports.[26] This was contradicted by President Salva Kiir, who announced South Sudan had begun the application process one month later.[27] The application was deferred by the EAC in December 2012,[28] however incidents with Ugandan boda-boda operators in South Sudan have created political tension and may delay the process.[29]

In December 2012, Tanzania agreed to South Sudan's bid to join the EAC, clearing the way for the world's newest state to become the regional bloc's sixth member.[30] In May 2013 the EAC set aside US$82,000 for the admission of South Sudan into the bloc even though admission may not happen until 2016. The process, to start after the EAC Council of Ministers meeting in August 2013, was projected to take at least four years. At the 14th Ordinary Summit held in Nairobi in 2012, EAC heads of state approved the verification report that was presented by the Council of Ministers, then directed it to start the negotiation process with South Sudan.[31]

A team was formed to assess South Sudan's bid; however, in April 2014, the nation requested a delay in the admissions process, presumably due to ongoing internal conflict.[32][33]

South Sudan's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Barnaba Marial Benjamin, claimed publicly in October 2015 that, following evaluations and meetings of a special technical committee in May, June, August, September and October, the committee has recommended that South Sudan be allowed to join the East African Community. Those recommendations, however, had not been released to the public. It was reported that South Sudan could be admitted as early as November 2015 when the heads of East African States had their summit meeting.[34]

South Sudan was eventually approved for membership to the bloc in March 2016,[35] and signed a treaty of accession in April 2016.[36] It had six months to ratify the agreement, which it did on 5 September, at which point it formally acceded to the community.[37][38] It does not yet participate to the same extent as the other members.[19][timeframe?]

Democratic Republic of the Congo's accession

[edit]In 2010, Tanzanian officials expressed interest in inviting the DR Congo to join the East African Community. The DRC applied for admission to the EAC in June 2019.[39] In June 2021, the EAC Summit launched a verification mission to assess the suitability of the DRC for admission to the Community, and has since drafted a report on their findings which is ready for submission to the EAC Council of Ministers.[40] On 23 November 2021: Ministers in charge of East African Community (EAC) Affairs have recommended for consideration by the EAC Heads of States the report of the verification team on the application by The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to join the Community.[41] In February 2022, the EAC Council of Ministers recommended that the DRC be admitted as a new member state of the EAC.[42] On 18 March 2022, the EAC Secretary-General Peter Mathuki confirmed that the Heads of State would approve the admission on 29 March 2022.[43] The Democratic Republic of the Congo was admitted as a member of the EAC on 29 March 2022, at a virtual Head of State summit chaired by Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya,[44] and officially became a member of the East African Community on 11 July 2022 after depositing the instrument of ratification with the EAC Secretary General at the bloc's headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania. The accession of the DRC gives the EAC its first port on the West African coast.

Somalia's accession

[edit]Representatives of Somalia applied for membership in the EAC in March 2012.[45] The application was considered by the EAC Heads of State in December 2012, which requested that the EAC Council work with Somalia to verify their application.[46] In February 2015, the EAC again deliberated on the matter but deferred a decision as verification had not yet started nor had preparations with the Somali government been finalized.[47] During the 22nd Ordinary EAC Heads of State Summit on 22 July 2022, the EAC Heads of State, noted that the verification process for Somalia to join the community needs to be completed expeditiously.[48] In 2023, East African Community (EAC) Secretary-General Peter Mathuki said Somalia had made a critical step towards becoming the eighth member of the bloc, with negotiations on admission set to last from 22 August to 5 September.[49] Somalia was formally invited to join on 24 November 2023 during the 23rd ordinary summit of the heads of state, following a five-hour closed-door meeting.[50][51] The treaty of accession was signed on 15 December 2023 at the presidential residence in Kampala, Uganda, with Somalia having 6 months to complete its ratification of the treaty after which it would officially become a member.[52][53] On February 10, 2024, Somalia's Parliament endorsed the treaty of accession.[54] Somalia deposited its instruments of ratification on 4 March 2024, thus becoming the eighth member of the organisation.[55]

Partner states

[edit]| Country | Capital | Accession | Population[3] | Area (km2) | GDP (US$ bn)[4] |

GDP per capita (US$) |

GDP PPP (US$ bn)[4] |

GDP PPP per capita (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gitega | 2007 | 13,590,102 | 27,834 | 3.075 | 226.27 | 12.241 | 900.73 | |

| Kinshasa | 2022 | 115,403,027 | 2,344,858 | 73.761 | 639.16 | 160.197 | 1,388.15 | |

| Nairobi | 2000 | 58,246,378 | 580,367 | 104.001 | 1,785.54 | 365.854 | 6,281.15 | |

| Kigali | 2007 | 13,623,302 | 26,338 | 13.701 | 1,005.70 | 46.658 | 3,424.87 | |

| Mogadishu | 2024 | 13,017,273 | 637,657 | 12.804 | 983.62 | 34.027 | 2,613.99 | |

| Juba | 2016 | 12,703,714 | 644,329 | 6.517 | 513.00 | 7.031 | 553.46 | |

| Dodoma | 2000 | 67,462,121 | 945,087 | 79.605 | 1,180.00 | 244.363 | 3,622.23 | |

| Kampala | 2000 | 49,283,041 | 241,550 | 56.310 | 1,142.58 | 156.696 | 3,179.51 | |

| 343,328,958 | 5,448,020 | 349.774 | 1,018.77 | 1,027.067 | 2,991.50 | |||

Potential expansion

[edit]Angola

[edit]In 2019, President Lourenço mediated the re-opening of the borders and ending hostilities between EAC neighbours Rwanda and Uganda. Historically, Angola has been closely involved politically with the DRC with a focus on peace and stability in the DRC. Angola is currently leading the Luanda process for stability in the eastern DRC under the ICGLR with EAC Partner States – Uganda and Rwanda.[56][57]

Central African Republic

[edit]EAC partner states Burundi, DR Congo, Rwanda, and Tanzania have been involved in peace keeping missions in the Central African Republic. President Touadera has applauded Rwanda's support in securing peace in the country. With DRC in the EAC, and infrastructure developments from Pointe-Noire in the Republic of Congo to Bangui, the capital of the CAR, as well as inclusion of the country into the LAPSSET project from Lamu-Juba-Bangui-Douala, this could see the mineral and resource rich country realize economic benefits.[58][59]

Comoros

[edit]In July 2023 Kenyan President William Ruto raised the idea of Comoros joining the EAC while signing an agreement for deeper bilateral cooperation between Kenya and Comoros. Comoros and existing member Tanzania have a maritime border.[60]

Republic of the Congo

[edit]The Republic of the Congo enjoys strong historical political, economic and cultural ties with DR Congo. The Republic of Congo is involved, under the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), in the peace and stability efforts in eastern DR Congo together with Angola. Rwandan and Ugandan leaders have been meeting in Luanda with President Sassou Nguesso to support these peace efforts.[57][61]

Djibouti

[edit]With Somalia set to join the group in October 2023, Secretary General Peter Mathuki stated, “The vision of our leaders is to have a market of 800 million people. And that will be possible if we integrate all the countries in the horn of Africa and make one huge market,” hinting of the possible accession of Djibouti and Ethiopia.[62]

Ethiopia

[edit]Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta proposed expanding the EAC to include Central, Northern, and Southern African states, such as Ethiopia.[63] The potential joining of Ethiopia into the EAC would bring the population to approximately 460 million.[3] Speaking at the opening of the One Stop Border post in Moyale in 2020, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia affirmed his commitment to regional integration saying that the east African people are one people and economic integration is a key goal for the region to achieve so as to unlock its potential.[64][65] With other horn of Africa countries like Somalia joining the EAC and the opening up of Ethiopia's sectors such as banking and telecommunications to the private sector, being part of the EAC could soon become a priority to accelerate economic gains.[66] In April 2023, Secretary General Peter Mathuki suggested the EAC should consider admitting Ethiopia following Somalia's accession.[67] On 8 April 2024, Ministry of EAC Arid and Semi-arid Lands and Regional Development Cabinet Secretary Peninah Malonza claimed the EAC and Ethiopia were in the final stages of negotiation for admission into the bloc.[68] This was later contradicted by Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Nebiu Tedla who said that Ethiopia had made no request to join the EAC and that "the information is baseless."[69]

Malawi

[edit]In 2010, Tanzanian officials expressed interest in inviting Malawi to join the EAC. Malawian Foreign Affairs Minister Etta Banda said, however, that there were no formal negotiations taking place concerning Malawian membership.[70]

Mozambique

[edit]Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni in May 2022, hinted at the possibility of deploying an East African regional force to Mozambique to counter insurgency in the Northern Provinces. Rwanda, at the request of Mozambique, in July 2021 had sent a strong contingent to Cabo Delgado. Mozambique shares cultural and historical ties with EAC Partner States. There is a significant Kiswahili speaking population in the country.[71][72]

Sudan

[edit]Sudan applied to join the EAC in 2011, with Burundi, Kenya, and Rwanda supporting membership, while Tanzania and Uganda were opposed to it. They contended that because of the Sudan's lack of a direct border with the EAC at the time, its allegedly discriminatory actions toward black Africans, its record of human rights violations, and its history of hostilities with both South Sudan and Uganda, Sudan was ineligible to join and their application was rejected in December 2012.[73][74]

EAC Organs

[edit]The Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community established seven EAC Organs to perform the functions of the community.

The Summit

[edit]| Period | Chairman |

|---|---|

| 2012–2013 | |

| 2013–2015 | |

| 2015–2017 | |

| 2017–2019 | |

| 2019–2021 | |

| 2021–2022 | |

| 2022–2023 | |

| 2023–2024 | |

| 2024-Present |

The Summit consists of the heads of state of each individual member country. The Summit gives "strategic direction towards the realization of the goal and objectives of the Community," and convenes once per year, with additional meetings at request of any member of the Summit. The Summit's decisions are arrived at by consensus.[75] The Chairperson of the Summit's tenure is one year and is in rotation from among the partner states. At Summit meetings, the Summit reviews annual progress reports and other reports from the Council. The summit appoints East African Court of Justice judges, assents to bills, and admits new member or observer states. The Summit may delegate many but not all of its powers to lower organs at the discretion of the Summit. The President of Kenya, William Ruto, serves as the current EAC Summit Chairperson.[76]

The Council

[edit]The Council consists of the Minister responsible for EAC affairs of each member State, any other Minister of the member state the member state elects; and the Attorney General of each Partner State. The Council meets twice a year, one time directly after the Summit and once later in the year.[75] The Council can also meet at the request of the Council Chairperson or member state. The Council main function is to implement decisions made by the Summit. The Council initiates and submits Bills to the Assembly, gives directions to the Partner States, and makes regulations, issues directives, and makes recommendations to all other organs (except the Summit, the Court, and the Assembly).[75] The Council also can establish Sectoral Committees from amongst its members to implement specific directives. Deng Alor Kuol, the Minister for East African Community Affairs in South Sudan, is the current Chairperson of the EAC Council of Ministers.[39] This position of Lead Council Chairperson is elected by the Head of State, and is replaced annually.[75]

The Coordination Committee

[edit]The Co-ordination Committee consists of the Permanent Secretaries of EAC affairs in each member state and any other Permanent Secretaries as determined by the member state. The Coordination Committee meets at least twice a year preceding the meetings of the Council. The Coordination Committee implements the directives decided by the Council and recommends the creation of Sectoral Committees to the Council.[75] The current acting Principal Secretary of the Coordinating Committee is Dr. Kevit Desai of Kenya.[77]

East African Court of Justice

[edit]The East African Court of Justice is the judicial arm of the community and consists of the First Instance Division and an Appellate Division. The Judges are appointed by the Summit from candidates recommended by the member states provided there are no more than two judges of a member state on the First Instance Division and no more than one judge of a member state on the Appellate Division.[75] The court is composed of a maximum of fifteen judges with no more than ten of the First Instance Division and no more than five of the Appellate Division. Each Judge may serve for no more than seven years and holds office until that period expires, death, reaching seventy years-of-age, or removal for misconduct by the Summit after deliberation from a tribunal, bankruptcy, or conviction.[75] Upon suspension, the judge's member state recommends a qualified candidate for appointment to temporary judge. If a judge has a conflict-of-interest, they are to report to their higher-up for deliberation on their ability to fairly judge.[75] The court has jurisdiction over cases involving interpretation and application of the treaty, other jurisdiction as designated by the Summit, member states that consider another member state or EAC Organ to have failed obligations under the treaty, and disputes between the EAC and its employees.[75] The Summit, the Council, or a Partner State may also request the Court to give an advisory opinion on an issue regarding the Treaty.

East African Legislative Assembly

[edit]

The East African Legislative Assembly (EALA) is the legislative arm of the community. The EALA has 27 members who are all elected by the National Assemblies or Parliaments of the member states of the community.[75] The EALA has oversight functions on all matters that fall within the community's work and its functions include debating and approving the budget of the community, discussing all matters pertaining to the community and making recommendations to the council as it may deem necessary for the implementation of the treaty, liaising with National Assemblies or Parliaments on matters pertaining to the community and establishing committees for such purposes as it deems necessary.[75] The Assemblypersons have a term of five years and a term limit of two. The EALA meets at least once a year and since being inaugurated in 2001, the EALA has had several sittings as a plenum in Arusha, Kampala, and Nairobi. Any member may introduce a bill and upon a simple majority vote, the bill proceeds to the Heads of State in which if any Head of State declines to assent within three months, the bill heads back to the EALA for editing.[75]

As of August 2024, the Speaker of the Assembly is Dan Kidega from Uganda. He replaced former Speaker of the Assembly and Ugandan MP Margaret Zziwa after her impeachment.[citation needed] She had succeeded Abdirahin Haithar H. Abdi from Kenya. The assembly has been credited with crucial bills, particularly those regarding regional and international trade, including EAC's stand on issues such as the World Trade Organization and transport on Lake Victoria.[78]

The Secretariat

[edit]| Period | Secretary-General |

|---|---|

| 2000–2001 | |

| 2001–2006 | |

| 2006–2011 | |

| 2011–2016 | |

| 2016–2021 | |

| 2021–2024 | |

| 2024–present |

The Secretariat is the executive organ of the EAC. The highest office of the Secretariat is the Secretary General. The Secretary General is appointed by the summit upon nomination by the current rotational head of state and serves one five-year fixed term.[75] The Secretariat also contains the offices of the Deputy Secretaries General appointed by the Summit and under the purview of the Secretary General. The Secretariat's principle function is the implementation of the decisions of the Summit and the Council with other functions including research on best methods to achieve the EAC treaty's goals, management of funds, and investigation of EAC affairs.[75] Veronica Nduva is the current Secretary General of the EAC,[76] having been appointed 7 June 2024 following Kenya's recall of former EAC Secretary-General Peter Mathuki for alleged misallocation of six million in funds from the Peace Fund at the Secretariat.[79]

EAC Institutions

[edit]There are eight current Heads of EAC Institutions. Vivienne Yeda Apopo of Zambia is the current acting Director-General of East African Economic Development and has had this position since 2009.[80] Dr. Novat Twungubumwe of Burundi is the current acting Attorney General and Executive Secretary East African Health Research Commission.[81] Dr. Sylvance Okeyo Okoth is the Executive Secretary of the East African Science and Technology Commission (EASTECO).[82] Dr. Caroline Asiimwe of Uganda is the serving Executive Secretary of the East African Kiswahili Commission.[77] Prof. Gaspard Banyankimbona of Uganda is the serving Executive Secretary of the Inter-University Council for East Africa.[77] Eng. Richard Gatete of Rwanda is the serving executive director of the Civil Aviation Safety and Security Oversight Agency.[77] Lilian K. Mukoronia of Kenya is the acting Registrar of the East African Community Competition Authority.[77] Dr. Masinde K. Bwire is the serving Executive Secretary Lake Victoria Basin Commission.[77]

Issues

[edit]Support

[edit]An EAC political union committee conducted a study on the support for the planned political union in the then-five member states from 2007 to 2009. Except for Tanzania, these committees found that the majority of their populations were in favour of further integration. While the committee continued to study integration until 2012, enthusiasm for the idea waned.[83]: 13.9–13.10

| Country | EAC "helps a lot" |

EAC "helps some- what" |

EAC "helps a little" |

EAC does nothing |

Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uganda | 20% | 21% | 15% | 7% | 37% |

| Kenya | 16% | 28% | 27% | 8% | 20% |

| Tanzania | 16% | 28% | 13% | 16% | 28% |

Surveying of Tanzania in 2012 by independent research group Afrobarometer revealed that 70% of Tanzanians approved of free movement of people, goods, and services.[84] Meanwhile, 55% of Tanzanians approve the customs union and 54% approve of the proposed monetary union.[84] On all three issues, share of people answering "Don't Know" has more than halved since 2008 indicating higher rates of civic engagement on EAC issues.[84] Approval of a joint army went from 26% in 2008 to 38% in 2012, with the majority (53%) still disapproving.[84] In Kenya, approval for the free movement of people, goods, and services was at 52% as of 2021.[85] Support for the monetary union sat at 49%, with 44% disapproving.[85] 65% of those with no lived poverty approved of the free movement policy while only 44% of those with high lived poverty supported it.[85] Surveying in May 2015 in Uganda found that 69% support free movement across borders in the region.[86] In Burundi, 64% supported free movement among the region.[86] A combined 56% of Ugandans thought the EAC "helps a lot", "helps somewhat", or "helps a little" in their country.[86] 71% of Kenyans thought the EAC helps in some capacity while 57% of Tanzanians thought the EAC helps in some capacity.[86][note 1]

Awareness of EAC Organs in Kenya is low; 43% had heard nothing of the EALA, with only 29% hearing "some" or "a great deal".[85] 47% of Kenyans said that their EALA representatives should be elected directly instead of elected by the Kenyan Parliament.[85]

Much of the support for East African integration comes from the national elites. Old enough to remember the former EAC, many are nostalgic for that period of East African politics and regret its eventual dissolution.[87] However, 61% of the 18-25 demographic supported free movement in Kenya while only 43% of the 46-55 demographic supported it.[85] This could be due to a growing sense of East African identity in the youth developing from modern communications.[87] The group with highest support for free movement in Kenya was those with post-secondary education, with 73% supporting.[85]

Budget deficit

[edit]The EAC is critically underfunded due to defaulting member states. Kenya is the only member state to not have any standing debt while all other member states have significant arrears of some kind; As of November 2024, the DRC owes US$20 million, Burundi US$17 million, South Sudan US$15.6 million, Somalia US$7 million, Rwanda $5.2 million and Uganda US$3.4 million.[88] Tanzania has been said to owe US$7 million though that number has been disputed by Secretary General Veronica Nduva.[88] Somalia has contributed US$7.8 million following its accession,[89] putting it ahead of the DRC which, despite accessing in 2019, had yet to remit a cent until 2024 when it remitted US$1 million to the EAC.[88] In the 2023–24 fiscal year, arrears amounted to over US$35 million.[90] Reasons for these arrears are primarily due to two factors:

- Failure to enforce contributions via sanctions outlined in the treaty

- Member states's contributions to the budget are equal despite their varying sizes and GDPs

The equal-share model was adopted when the EAC comprised only Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, and may no longer be sustainable.[91] An alternate payment model has been proposed in which 65% of the budget is contributed to equally, while the remaining 35% is contributed to on the basis of each member states' respective average nominal GDP in the past five years.[91] EALA Chairperson of the Budget Committee Ken Mukulia suggests amendments to the EAC legal instruments to distribute power according to size of contribution should accompany the new financing model.[91] Additionally, auctioning stranded goods in the ports of Dar es Salaam and Mombasa slated for the three major defaulters has been suggested as a method of paying off their debt.[92] Both Mukulia and Rwandan President Paul Kagame have proposed sanctioning defaulting member states.[91][93]

Despite calls for reform, the financial year 2024/2025 EAC budget will be contributed to equally.[90] 61% of that budget will be equally contributed from member states or raised by internal revenue while 39% will be sourced from development partners.[90] The budget for financial year 2024/25 is US$112.98 million, a 8.7% increase from last financial year.[90] The majority of this increase has been attributed to Somalia's accession.[89] As of 25 November 2024, only US$13.3 million of the $89.5 million budget for financial year 2024/2025 has been remitted.[88] Chairperson of the EALA Budget Committee Ayason Mukulia stated that the failure in remission may stem from hesitancy following the misallocation of US$6 million in funds from the Secretariat by former Secretary General Peter Mathuki.[88] Member states have reportedly refused to remit funds until a full audit is conducted.[88]

DRC-EAC tensions

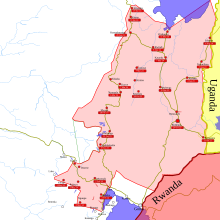

[edit]The M23 offensive

[edit]The March 23 Movement, a Congolese rebel military group composed mostly of ethnic Tutsi,[94] waged a rebellion in the northeastern DRC from 2012 to 2013. M23 was formed by deserters of the DRC Armed Forces (FARDC) who had previously been members of the CNDP rebel group and been dissatisfied with the conditions of their service. Both the CNDP as well as the March 23 Movement's first rebellion were supported by Rwanda and Uganda.[95][96] A United Nations report found that Rwanda created and commanded the M23 rebel group.[97] Rwanda ceased its support because of international pressure and the military defeat by the DRC and the UN in 2013.[98] After agreeing to a peace deal, M23 was largely dismantled, its fighters disarmed and moved into refugee camps in Uganda.[95] In 2017, an M23 splinter group fled Uganda to Kivu to resume their insurgency,[99] however, the operation achieved little as the M23 no longer enjoyed significant international support. Uganda and the DRC had greatly improved relations, cooperating against a common enemy in the Allied Democratic Forces[99] during Operation Shujaa. In early 2022, a growing number of M23 combatants began leaving their camps and move back to the DR Congo;[95] the rebel movement launched more attacks in February 2022, but these were repelled.[99] The M23 leadership argued that parts of their movement had resumed the insurgency because the conditions of the 2013 peace deal were not being honored by the DRC government.[95][96] The rebels also argued that they were attempting to defend Kivu's Tutsi minority from attacks by Hutu militants such as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR).[100] This follows a long trend of Hutu-Tutsi violence, exemplified by the Burundi genocide of 1993 and the Rwandan genocide of 1994, the latter having been stopped by current President of Rwanda Paul Kagame, an ethnic Tutsi who has remained in power over the Hutu-majority country since the end of the genocide.

On 6 April 2022, the FARDC rejected any negotiations with the M23 forces based in the DR Congo, and started a counter-attack.[101] However, as the FARDC was increasingly losing ground to the insurgents, the DRC government and a number of rebel groups held peace talks in Nairobi in late April, only for the offensive to resume in May.[101] In late May, insurgents temporarily seized Rumangabo before it was retaken by the FARDC. According to independent researchers, the insurgents were supported by Rwandan soldiers during the battle for Rumangabo.[102] Following months of attempts, on 13 June 2022, M23 captured the town of Bunagana. FARDC spokesman Sylvain Ekenge declared that the fall of Bunagana constituted "no less than an invasion" by Rwanda.[103] Two senior Congolese security sources and members of the Congolese parliament also accused Uganda of supporting the rebel offensive.[104] The Congolese MPs claimed that the retreat of the Uganda People's Defense Force before the rebel attack had facilitated the takeover of Bunagana. The DRC ended military cooperation with Uganda, leading to Uganda subsequently halting Operation Shujaa.[105] Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta responded to the fall of Bunagana and the growing regional tensions by calling for the EAC to immediately organize a new peacekeeping mission called the East African Regional Force to restore security in the eastern DR Congo.[106] An EAC meeting was organized in Nairobi to discuss the diplomatic tensions between the DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda, as well as the deployment of a new peacekeeping force. The DRC declared that it would welcome an EAC peacekeeping mission but only under the condition of Rwanda's exclusion from the operation.[107][108] The EAC subsequently called on M23 to retreat from Bunagana[109] as precondition for a ceasefire, but the insurgents rejected the order.[110] Anti-Rwandan protests broke out on 31 October in Goma, demanding that the DRC leave the EAC and that Russia intervene in the conflict. On 2 November, Kenya announced that it would send 900 soldiers to fight against the M23.[111] The Ugandan military then joined the Kenyan troops in fighting the M23.[112] On 28 December 2022, South Sudan sent a contingency of 750 troops to join the EARF, to be stationed in Goma.[113] Over the next few months, the EARF made some ground, with various towns being ceded to the EARF.[114] On 3 April, Ugandan EARF soldiers entered Bunagana. However, instead of taking the city, the EARF coexisted with the rebel forces.[115] A similar arrangement was also observed at Rumangabo, where Kenyans and M23 inhabited the same base, and along the Sake-Kilolirwe-Kitshanga-Mwesso axis, where Burundian and rebel forces operated next to each other.[116]

In October 2023, the DRC ordered the EAC force in the country to leave by 8 December, due to a "lack of satisfactory results on the ground".[118] On 19 December 2023, the last of the EARF forces had withdrawn from the Eastern DRC.[119] To replace the EARF, SADC forces on 15 December 2023 were deployed to the region to “restore peace and security in the eastern DRC”.[120]

Rumours of DRC exit

[edit]At the 24th Ordinary Summit held in November 2024, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi, expected to take over as Summit Chairperson, neither attended nor sent a representative, with Kenyan President William Ruto elected to the position instead.[93] This follows a series of absences by Tshisekedi, including the 23rd Extraordinary Summit, held on 7 June 2024 to appoint Veronica Mueni Nduva as Secretary General.[121] Insiders at the Secretariat have stated that the DRC rarely takes part in meetings and as of 22 June 2024, the DRC has yet to align its legal instruments with the EAC as per the treaty.[121] The DRC has implemented free movement of people however otherwise has not integrated to the extent the other member states have.[121] The DRC is required to remit money yearly to the EAC as part of its membership; however, despite accessing in 2019, it had failed to remit a cent until 2024 when it remitted US$1 million to the EAC.[88] The DRC still owes a total of US$20 million.[88]

Analysts have suggested that the DRC’s continued absence is a boycott in response to Kenyan President William Ruto’s stance on the M23 conflict.[121] At a summit meeting, there was a discussion on if the M23 were Rwandan or Congolese. Ruto said “the DRC told us: ‘They are Congolese.’ End of the debate. If they are Congolese, how does this become a Rwandan problem? How does this become a Kagame problem?”[122]

Former Foreign Minister of the DRC Christophe Lutundula said the DRC strategy was “to join the Eastern bloc, of course for regional integration and economic reasons, but also to better plead the Congo’s security cause, where Rwanda is making its voice heard,” suggesting that EAC accession to the EAC was in large part due to counteracting Rwanda's influence in the bloc.[121] Congolese legislators in the EALA said the DRC was not considering quitting the EAC, but that the decision was up to President Tshisekedi.[121]

MP Bertran Ewanga, head of the DRC chapter of the EALA, suggested that additional tension arose from a statement by Kenyan President William Ruto during a state dinner with U.S. President Joe Biden, although the specific statement that caused the tension is unknown.[121] DRC Spokesman Patrick Muyaya said the peace in Kivu was taking too long to be realised and that “some Congolese are now questioning why we even asked to join the EAC.”[121] He also said the DRC is "happier in the SADC than in the EAC," reflecting the EARF's replacement at request of Tshisekedi with SADC forces.[121]

Tshisekedi recalled the ambassador of the DRC to Kenya in December 2023 and has yet to accredit the new Kenyan ambassador to the DRC due to disagreements surrounding the Congo River Alliance, a group including DRC politicians and various secessionist militias including the M23.[121][123][93] Tshisekedi demanded that Kenya hand over any persons engaging in "subversive activities," to which Kenyan foreign minister Musalia Mudavadi said “Kenya strongly disassociates itself from any utterances or activities likely to injure the peace and security of the friendly nation of DRC and has commenced an investigation.”[123] Ultimately, Kenya found the statements to fall under constitutionally protected speech.[121]

The DRC's entry into the EAC was facilitated by Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, Ruto's predecessor and a friend to Tshisekedi. Ruto is seen as reversing the positions that allowed the DRC to join in the first place.[121] DRC Opposition leader Martin Fayulu has called the DRC’s membership in the EAC a “big mistake”.[121] The EAC treaty has no provisions for the forcible exit of a member state, with only sanctions having been outlined.[121] During the 7 June 2024 Summit, Paul Kagame called for a meeting of the Council of Ministers to discuss peace in the region.[121]

Despite conflicts, Secretary General Veronica Nduva said in November 2024 that the DRC is finalising a review of its policy and legal framework to align with EAC protocols, including waiving visa requirements for citizens of all EAC partner States.[88]

Somali integration

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

As of July 2024, Somalia is active in an ongoing civil war. The main insurgent group is the Al-Qaeda-linked, Sunni Islamist military Al-Shabaab. Although based in Somalia, its reach extends all the way to Kampala, Uganda, where it killed 76 people in a 2010 Kampala bombings. As a result of the ongoing civil war, Somalia topped the annual Fragile States Index for six years from 2008 up to and including 2013.[124] Troops from Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Burundi and Djibouti have fought Al-Shabaab since 2007, first as the African Union Mission to Somalia then as African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS). However, as of July 2024, 5,000 soldiers have left Somalia as ATMIS prepares to leave Somalia by December 2024.[125] Recently, Al-Shabaab have allied with the Ugandan rebel group, the Allied Democratic Forces, trading arms and training for illegally-mined minerals from the Eastern DRC.[125] Al-Shabaab has also created a sect of foreign fighters called the Muhajirin, including primarily Kenyan, Ethiopian and Tanzanian nationals, but also some Congoleses, Burundians, Rwandans and Ugandans.[125] In 2024, Al-Shabaab recaptured much of the land captured by the retreating ATMIS.[125]

Most of Somalia operates independently from its federal government. Somaliland, an internationally unrecognized state within the borders of Somalia, released a statement following Somalia’s accession into the EAC stating that the “decision is a clear violation of Somaliland's sovereignty and territorial integrity,” and called for the EAC, the African Union, and the United Nations to recognize their statehood.[126] In addition, Puntland has temporarily withdrawn until the constitutional amendments concentrating power under president Hassan Sheikh Mohamud are approved in a nationwide referendum.[127] These conflicts have caused the federal government to control only around ten percent of its internationally-recognized territory as of May 2024.

Differences in modes of governance

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

Despite efforts at integration and standardizing governance, there remains significant political differences between the states. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni's success in obtaining his third-term amendment raised doubts in the other countries.[87] The single-party dominance in the Tanzanian and Ugandan parliaments is unattractive to Kenyans, while Kenya's ethnic-politics remains absent in Tanzania.[87] Rwanda has a distinctive political culture with a political elite committed to building a developmental state.[87]

These differences in modes of governance was exemplified when South Sudanese President Salva Kiir Mayardit was appointed chairperson of the EAC in November 2023. This decision was criticized by some regional observers including Duop Chak Wuol, an influential South Sudanese analyst, who criticized the appointment of Kiir, seeing it as evidence of the EAC failure to uphold its moral obligations and accused the bloc of ignoring what he described as Salva Kiir's tyranny.[128] Many have argued that support for East African integration from local politicians grants often corrupt politicians with the ability to present themselves as statesmen and representatives of a greater regional interest.[87] Furthermore, EAC institutions bring significant new powers to dispose and depose to those who serve in them.[87]

Economics

[edit]Importance of the customs union

[edit]The key aspects of the customs union include:[87]

- a Common External Tariff (CET) on imports from third countries;

- duty-free trade between the member states; and

- common customs procedures.

The CET's default rate is 25%.[129] The CET for goods can range from 0% to 100% in the case of sugar.[130] For the most part, goods do not exceed a CET of 35% except for "sensitive items" which include dairy products, maize, rice, and woven fabrics.[130] Recently, the Council of Ministers has agreed to duty remission for raw materials needed to stimulate EAC domestic production.[129] Kenya was also granted a temporary exception to the CET to import grain at a lower tariff to meet local demand and increase food security.[129] The customs union is not yet exercised in the full extent of the promise. For instance, Kenya still holds excise duties on many products, raising excise duty rates in 2023.[131] And although Kenya recently loosened certain duties, they still haven't enacted full free movement of goods.[129] This also means that countries outside of the EAC must still navigate local tax and duties opposed to a singular tax policy, simplifying the process of investing in EAC member states. For EAC internal trade in the third quarter of 2023, Tanzania was the biggest exporter with US$798.12 million, Uganda was the biggest importer with US$649.3 million, and Rwanda had the highest internal EAC in trade deficit of US$375.23 million.[132] Intra-regional trade currently stands at 15% of EAC trade according to Summit Chairman Salva Kiir, which was deemed unsatisfactory.[76]

Common market

[edit]

On 1 July 2010, the EAC launched the Common Market Protocol, an expansion of the bloc's existing customs union that entered into effect in 2005.[133] Corruption has led to some integration initiatives being underfunded.[134] The full adoption of the common market has been undermined by continued protectionism between member states, with decisions driven by political pressures on national leaders slowing down the implementation of commitments to integration, even within founding members.[83]: 13.13 Bilateral political tensions have led to border controls in some periods, further undermining the shared labour market. In 2024, Rwanda closed its borders with Burundi and the DRC, after a previous three-year closure of its border with Uganda in 2019.[88] In January 2023, Burundi closed its border with Rwanda after President Evariste Ndayishimiye accused Rwanda of hosting and training the RED-Tabara rebel group.[88]

Despite border closings, an immense amount of inter-EAC migration is still occurring; From July to December 2023, around 376,000 citizens emigrated to Rwanda from other EAC member states, including around 76,500 Burundians.[88] In turn, Burundi received around 251,500 citizens from other EAC member states, including 110,500 Rwandans.[88] South Sudan received 69,584 citizens, half of which were from Uganda.[88]

In 2010, the introduction of "third generation" ID cards was planned. These cards identify the holder as a dual citizen of their home country and of "East Africa".[135] Third generation cards are already in use in Rwanda with Kenya set to introduce them in July 2010 and the other countries following afterwards.[136] An East African passport was launched on 1 April 1999 in the original three countries of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.[137] The 17th Ordinary Summit held on 2 March 2016 launched the East African electronic passport. Tanzania started issuing the EA e-passport on 31 January 2018; Kenya and Burundi on 28 May 2018; Uganda on 18 December 2018 and Rwanda on 28 June 2019. South Sudan, the DRC and Somalia are still establishing the legal framework to start issuing the document.[88] Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda, allow citizens to travel within their territories using a national ID as a travel document.[88] Mutual recognition and accreditation of higher education institutions is also being worked towards as is the harmonisation of social security benefits across the EAC.[136]

Emerging business trends

[edit]Business leaders are far more positive than economists about the benefits of EAC integration, its customs union as a step in the process, as well as the wider integration under COMESA.[87] The larger economic players perceive long-term benefits in a progressively expanding regional market.[87] Patterns of regional development are already emerging, including:[87]

- Kenyan firms have successfully aligned to the lower protection afforded by the EAC CET and fears that firms would not adjust to a 25% maximum CET, or would relocate to Tanzania or Uganda have not been realised.

- An intraregional division of labour is developing, which results in basic import-processing relocating to the coast to supply the hinterland. The final stages of import-processing (especially those bulky finished goods that involve high transportation costs) and natural-resource based activities are moving up-country and up-region, either within value chains of large companies or different segments located by firms in different countries.

- Trade in goods and services has already increased as service provision to Kenyans and Tanzanians is already important for Uganda (in education and in health). Kenya exports financial services, for example via the Kenya Commercial Bank and purchase and upgrading of local operators in Tanzania, Uganda and Sudan. Uganda hopes integration will help support its tourism potential through integration with established regional circuits.

- There are signs of a business culture oriented to making profits through economies of scale and not on protectionism.

- Kenya historically has been the leader in intraregional trade. For the first time in 2024, Tanzania overtook Kenya's position, leading regional trade.[93]

Due to the DRC's accession into the EAC, Congolese in Kisangani and Goma are now receiving their goods through ports in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam.[121] The success of this new trade route has caused the DRC and South Sudan to integrate revenue systems to streamline cargo documentation, hastening the rate at which goods are cleared through the Port of Mombassa.[138] The eastern region of the DRC currently has plentiful mining operations, in particular the mining of Cobalt. The mining sector of the EAC contributes around 2.3% of the GDP, with gold being the second highest exported product following petroleum in the fourth quarter of 2023.[139] In the Southeastern DRC lays the copperbelt, known for its copper mining. The copper is currently majority exported via road with the exception of the Lobito Atlantic Railway, which stretches from the Lobito, Angola to Kolwezi. However, the Lobito Corridor project, with $250 million in U.S. financial investment, would construct around 550 km (350 miles) of railway in Zambia along the Zambia-DRC border, with feeder roads connecting DRC copper mines to the new railway.[140]

Trade negotiations

[edit]On 16 July 2008, the United States and the EAC signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement, strengthening United States-EAC trade.[141] The U.S. exported $1.1 billion and imported $1.3 billion from the EAC in 2022. This shifted the net goods traded from a total trade deficit of $211 million in 2021 to a trade surplus of $135 million in 2022.[141] In Q4 2024, the EAC exported US$6.3 Billion.[132] Out of trade partners, the top five were China, the United Arab Emirates, India, South Africa, and Malaysia. The top importer of EAC goods was the UAE and the top source of inputed goods was China.[132] Trade with COMESA accounted for 11.5% of total EAC Trade while trade with SADC accounted for 12.9.[132]

Poverty reduction

[edit]EAC that have economies have large informal sectors, unintegrated with the formal economy and large business.[87] The concerns of large-scale manufacturing and agro-processing concerns are not broadly shared by the bulk of available labour.[87] Research suggest the promised investments on the conditions of life of the region's overwhelmingly rural poor will be slight, with the significant exception of agro-industrial firms with out-grower schemes or that otherwise contribute to the co-ordination of smallholder production and trade.[87]

It is informal trade across borders that is most often important to rural livelihoods and a customs union is unlikely to significantly impact the barriers that this faces and taxes are still being fixed separately by countries.[87] However, the introduction of one-stop border posts being introduced and the reduction in tariff barriers are coming down progressively.[87]

The establishment of a common market will create both winners (numerous food producers and consumers on both sides of all borders) and losers (smugglers and the customs, police and local government officers who currently benefit from bribery at and around the borders) in the border areas.[87] More substantial impact could be attained by a new generation of investments in world-market production based on the region's comparative advantages in natural resources (especially mining and agriculture) and the new tariff structure creates marginally better conditions for world-market exporters, by cheapening inputs and by reducing upward pressures on the exchange rate.[87]

Plans

[edit]The new treaty was proposed with plans drawn up in 2004 to introduce a monetary union with a common currency some time between 2012 and 2015. There were also plans for a political union, the East African Federation, with a common President (initially on a rotation basis) and a common parliament by 2010. However, some experts, like those based in the public think tank Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA), noted that the plans were too ambitious to be met by 2010 because a number of political, social and economic challenges are yet to be addressed. The proposal was the subject of National Consultative discussions, and a final decision was to be taken by the EAC Heads of State in mid-2007.[142] In 2013, a protocol was signed outlining their plans for launching a monetary union within 10 years.[9] There are concerns that rapid integration would enflame popular reactionary politics against the project.[87] However it's also been argued that, with high costs that would be required at the beginning, fast-tracking the project would allow the benefits to be seen earlier.[87]

Given the infrastructure problems that persist in the fledgling country since South Sudanese President Salva Kiir cut off oil commerce with Sudan, the state has decided to invest in constructing pipelines that circumvent Sudan's, which it had been using until that time. These new pipelines would extend through Ethiopia to the ports of Djibouti, as well as to the southeast to the coast of Kenya.[143]

In September 2018, a committee was formed to begin the process of drafting a regional constitution.[10]

In January 2023, the East African Community plans to issue a single currency within the next four years. The Council of Ministers of the organization must decide on the location of the East African Monetary Institute and the establishment of a roadmap for the issuance of the single currency.[144]

Coalition of the Willing

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (July 2024) |

A "Coalition of the Willing", made up of Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda, began a number of initiatives amongst themselves including joint railway and oil pipeline projects, a joint tourist visa, and a defence and security pact, to get around reluctance from other members.[83]: 13.14 However, even within this grouping, progress on projects has been delayed. Bilateral friction between members, a lack of enthusiasm, and political instability have been the primary reasons behind the delaying and weakening of integration efforts.[83]: 13.15

Single tourist visa

[edit]It had been hoped that an East African Single Tourist Visa may have been ready for November 2006, if it was approved by the relevant sectoral authorities under the EAC's integration programme. Had it been approved, the visa would have been valid for all three current member states of the EAC (Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda). Under the proposal for the visa, any new EAC single visa could be issued by any member state's embassy. The visa proposal followed an appeal by the tourist boards of the partner states for a common visa to accelerate promotion of the region as a single tourist destination and the EAC Secretariat wanted it approved before November's World Travel Fair (or World Travel Market) in London.[145] When approved by the EAC's council of ministers, tourists could apply for one country's entry visa which would then be applicable in all regional member states as a single entry requirement initiative.[146]

A single East African Tourist Visa for the EAC countries of Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda has been available since 2014.[147]

Demographics

[edit]| Name | Population[3] | % of Total Population | Annual Population Growth[3] | TFR | HDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 115,403,027 | 33.6% | 3.11% | 6.0 | 0.481 | |

| 67,462,121 | 19.6% | 2.72% | 4.5 | 0.532 | |

| 58,246,378 | 17.0% | 2.06% | 3.2 | 0.601 | |

| 49,283,041 | 14.4% | 3.18% | 4.2 | 0.550 | |

| 13,017,273 | 3.8% | 2.55% | 6.0 | 0.380 | |

| 13,623,302 | 4.0% | 1.62% | 3.6 | 0.548 | |

| 13,590,102 | 4.0% | 2.81% | 4.8 | 0.420 | |

| 12,703,714 | 3.7% | 4.65% | 4.1 | 0.381 | |

| 343,328,958 | 100% | 2.83% | 4.8 | 0.515 |

The population of the constituent parts of the EAC is composed of 65% under 30-year-olds.[148] This youth bulge is anticipated to grow to 75% of the population under the age of 25 in this region by 2030.[148]

The East African Community's current urban population stands at about 20%.[citation needed]

Languages

[edit]English is the official language of the EAC. Kiswahili was designated for development as the lingua franca of the community in 2000 with French added as a lingua franca in 2021.[1] Both the DRC and Burundi have French as an official language while English is not. Given this, there is an ongoing effort to elevate French to an official language, with France and the EAC signing an agreement in March 2020 to elevate French as an official language of the EAC alongside English.[1] France is financing around €42,500 toward the project, which has seen delays due to the Covid-19 pandemic.[1] Numerous local languages are also spoken: for example, there are 56 local languages spoken in Uganda,[149] 125 in Tanzania, 72 in South Sudan and 67 local languages in Kenya. Kinyarwanda is spoken in Rwanda and Uganda.[150] There are over 200 local languages spoken in the DRC. Lingala is widely spoken in the western Democratic Republic of Congo, with about 15 million speakers and Kiswahili with 23 million speakers across the country.[151]

Comparison with other regional blocs

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (November 2023) |

| African Economic Community | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillar regional blocs (REC) |

Area (km²) |

Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| (millions) | (per capita) | ||||

| EAC | 5,449,717 | 343,328,958 | 737,420 | 2,149 | 8 |

| ECOWAS/CEDEAO | 5,112,903 | 349,154,000 | 1,322,452 | 3,788 | 15 |

| IGAD | 5,233,604 | 294,197,387 | 225,049 | 1,197 | 7 |

| AMU/UMA a | 6,046,441 | 106,919,526 | 1,299,173 | 12,628 | 5 |

| ECCAS/CEEAC | 6,667,421 | 218,261,591 | 175,928 | 1,451 | 11 |

| SADC | 9,882,959 | 394,845,175 | 737,392 | 3,152 | 15 |

| COMESA | 12,873,957 | 406,102,471 | 735,599 | 1,811 | 20 |

| CEN-SAD a | 14,680,111 | 29 | |||

| Total AEC | 29,910,442 | 853,520,010 | 2,053,706 | 2,406 | 54 |

| Other regional blocs |

Area (km²) |

Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| (millions) | (per capita) | ||||

| WAMZ 1 | 1,602,991 | 264,456,910 | 1,551,516 | 5,867 | 6 |

| SACU 1 | 2,693,418 | 51,055,878 | 541,433 | 10,605 | 5 |

| CEMAC 2 | 3,020,142 | 34,970,529 | 85,136 | 2,435 | 6 |

| UEMOA 1 | 3,505,375 | 80,865,222 | 101,640 | 1,257 | 8 |

| UMA 2 a | 5,782,140 | 84,185,073 | 491,276 | 5,836 | 5 |

| GAFTA 3 a | 5,876,960 | 1,662,596 | 6,355 | 3,822 | 5 |

| AES | 2,780,159 | 71,374,000 | 179,347 | 3 | |

During 2004. Sources: The World Factbook 2005, IMF WEO Database.

Smallest value among the blocs compared.

Largest value among the blocs compared.

1: Economic bloc inside a pillar REC.

2: Proposed for pillar REC, but objecting participation.

3: Non-African members of GAFTA are excluded from figures.

a: The area 446,550 km2 used for Morocco excludes all disputed territories, while 710,850 km2 would include the Moroccan-claimed and partially-controlled parts of Western Sahara (claimed as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic by the Polisario Front). Morocco also claims Ceuta and Melilla, making up about 22.8 km2 (8.8 sq mi) more claimed territory.

| |||||

See also

[edit]- 17th EAC Extra Ordinary summit

- CASSOA

- EAC Railway Masterplan

- East African Federation

- East African Community Treaty

- East African School of Taxation

- Economy of Africa

- List of Trade blocs

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)

- Southern African Development Community (SADC)

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA)

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)

- Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

- Rules of Origin

- Market access

- Free-trade area

- Tariffs

Notes

[edit]- ^ Survey does not include option for "EAC harms"

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Wangari, Mary (15 November 2024). "Can EAC speak the same language? A linguistic challenge at Speakers' forum". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ @jumuiya (24 November 2023). "South Sudan has assumed Chairmanship of the East African Community" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c d e f "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: CIA World Factbook

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: CIA World Factbook

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook database: April 2024". imf.org. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ "East African Community continues on a trajectory of expansion as Summit admits Somalia into the bloc". Eac.int. 25 November 2023.

- ^ "East African Community – Quick Facts". Eac.int. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ "A political union for east Africa? – You say you want a federation". The Economist. 9 February 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "FACTBOX-East African common market begins". Reuters. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ a b "East African trade bloc approves monetary union deal". Reuters. 30 November 2013.

- ^ a b Havyarimana, Moses (29 September 2018). "Ready for a United States of East Africa? The wheels are already turning". The EastAfrican.

- ^ "From Co-operation to Community". eac.int. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008.

- ^ "EAC Update E-newsletter". eac.int. Directorate of Corporate Communications and Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "East African Economic Community". Crwflags.com. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ "– Born in anonymity". Ms.dk. Archived from the original on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ East African trade zone off to creaky start, Christian Science Monitor, 9 March 2006

- ^ We Celebrated at EAC Collapse, Says Njonjo.

- ^ "History of the EAC". EAC. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Aloo, Leonard Obura (2017), Ugirashebuja, Emmanuel; Ruhangisa, John Eudes; Ottervanger, Tom; Cuyvers, Armin (eds.), "Free Movement of Goods in the EAC", East African Community Law, Institutional, Substantive and Comparative EU Aspects, Brill, pp. 303–325, JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w76vj2.23, retrieved 21 February 2022

- ^ a b "Finally, EA nations agree to disagree on federation". The Citizen. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ a b "South Sudan: Big trading potential for EAC". IGIHE. 8 July 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ Mazimpaka, Magnus (8 July 2011). "South Sudan: Rwanda Hopeful of South's Strategic Link to North Africa". allAfrica. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "Welcome South Sudan to EAC!". East African Business Week. 10 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "South Sudan to link to Kenya oil pipeline". Reuters. 6 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "South Sudan needs African neighbours to survive". DAWN. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "South Sudan 'free to join the EAC'". The Citizen. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Amos, Machel (17 September 2011). "South Sudan delays membership in regional bloc". Daily Nation. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ "South Sudan readies for EAC membership". Archived from the original on 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Uganda says South Sudan likely to join EAC in 2014". Xinhua News Agency. 9 September 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Ugandan MPs oppose South Sudan joining East African community". The Africa Report. 7 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Tanzania warms up to South Sudan membership". The EastAfrican. 8 December 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "EAC prepares to admit South Sudan". The EastAfrican. 11 May 2013. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "allAfrica.com: East Africa: EAC to Decide On South Sudan Admission by April 2014". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "South Sudan defers EAC admission". The Observer. Observer Media Ltd. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "S. Sudan's push to join EAC gains momentum". The EastAfrican. 7 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "South Sudan admitted into EAC". Daily Nation. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Communiqué: signing ceremony of the treaty of accession of the Republic of South Sudan into the East African Community" (Press release). East African Community. 15 April 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Germany Ambassador pays courtesy call on EAC Secretary General" (Press release). East African Community. 9 May 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Republic of South Sudan deposits Instruments of Ratification on the accession of the Treaty for the establishment of the East African Community to the Secretary General" (Press release). East African Community. 5 September 2016. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ a b "DR Congo seeks to join EAC". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Kuteesa, Hudson (11 August 2021). "East Africa: Report on DR Congo Admission to EAC AwaitsMinisterial Decision". allAfrica. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "EAC Council of Ministers green-light Report on DRC Verification Mission for consideration by EAC Heads of State" (Press release). East African Community.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo inches closer to joining EAC" (Press release). East African Community. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Anami, Luke (21 March 2022). "DR Congo to join EAC next week". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Anami, Luke (29 March 2022). "DR Congo joins East African bloc". The EastAfrican. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Somalia applies to join EAC bloc » Capital News". Capital News. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Communiqué of the 14th ordinary summit of EAC heads of state". 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Not yet, S. Sudan and Somalia told by East Africa Community – Daily Nation". 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Communiqué of the 22nd ordinary summit of the East African Community heads of state" (Press release). East African Community. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Somalia set to join EAC this year, says Sec-Gen Mathuki". The EastAfrican. 19 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ Vincent Owino (24 November 2023). "Somalia officially admitted into EAC". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "East African Community continues on a trajectory of expansion as Summit admits Somalia into the bloc" (Press release). East African Community. 25 November 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Somali to sign Treaty of Accession with the East African Community today" (Press release). East African Community. 15 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Caato, Bashir Mohamed (29 November 2023). "Somalia has joined the EAC regional bloc. What happens next?". Al Jazeera English.

- ^ "Somalia close to formalise EAC membership". The EastAfrican. 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Somalia Deposits Ratification Instrument With EAC SG". Capital News. 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Tshisekedi, Kagame to meet in Angola over Congo war". 6 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Uganda, Rwanda presidents agree ceasefire after Angola, Congo mediation". 22 August 2019.

- ^ "In CAR, Rwandans lead East Africans in fight to keep a leader and nation alive". 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Lapsset project adopted by AU in move to boost continent's free trade area". 5 July 2020.

- ^ Aggrey Mutambo (8 July 2023). "Ruto woos Comoros to join EAC in quest for expanded bloc". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Rwanda's Kagame, DRC's Tshisekedi to hold talks in Angola". 4 July 2022.

- ^ Said, Mariam (5 October 2023). "Ethiopia, Djibouti to join EAC – Daily News". Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Kenyatta's EAC agenda: Admit more countries to regional bloc". The East African. 6 September 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Kenya's Uhuru & Ethiopia's Abiy Open Moyale One-Stop Border Post – Taarifa Rwanda". 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Ethiopia PM Abiy Ahmed speech at the new Lamu Port in Lamu County, 9 December 2020, retrieved 8 April 2022

- ^ "Ethiopia to Open up its Banking Sector to Foreign Competition – Kenyan Wallstreet". 23 March 2022.

- ^ Mathuki, Peter (1 April 2023). "Peter Mathuki: Why we want Addis to join EAC after Somalia". The East African (Interview). Interviewed by Jackson Mutinda. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Ethiopia set to join EAC, CS Malonza says". KBC. 8 April 2024. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Barden, Andrew (12 April 2024). "Ethiopia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs Refutes Reports of Joining EAC". The Kenyan Wall Street. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Daily Times | Malawi News | Sunday Times | The Weekend Times". The BNL Times. 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ "Museveni proposes regional force to counter Mozambique terrorist threat". 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Mozambique's President Filipe Nyusi arrives in Uganda for official visit". 27 April 2022.

- ^ Ihucha, Adam (18 September 2011). "EAC split on Khartoum's bid to join community". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ "Why Sudan's EAC application was rejected". 5 December 2011. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community" (PDF). East African Legislative Assembly. 20 August 2007 [30 November 1999; amended later]. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "Veronica Nduva sworn in as EAC Secretary-General". eac.int. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "EAC Organs". eac.int. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Removal of NTBs top priority for EAC". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015. [PDF]

- ^ "Peter Mathuki recalled". Nation. 19 March 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ "Ms Vivienne Yeda Apopo". eac.int. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Dr Novat Twungubumwe | EA Health". eahealth.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Message from Executive Secretary". eac.int. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Kasaija Phillip Apuuli (1 June 2023), "A Search for Political Integration in East Africa Community (EAC)" (PDF), GGW Africa Symposia Issue, 1

- ^ a b c d Knowles, Josie (July 2014). "East African Federation: Tanzanian Awareness of Economic and Political Integration Remains Poor, But There Is Growing Support for Political Links" (PDF). Afrobarometer (146).

- ^ a b c d e f g Kaburu, Mercy; Logan, Carolyn (23 August 2022). "Integrating states or integrating people? Kenyans have not heard much about the proposed East African Federation" (PDF). Afrobarometer (544).

- ^ a b c d Olapade, Markus; Selormey, Edem E.; Gninafon, Horace (25 May 2016). "Regional integration for Africa: Could stronger public support turn 'rhetoric into reality'?" (PDF). Afrobarometer (91).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t David Booth, Diana Cammack, Thomas Kibua and Josaphat Kwek (2007) East African integration: How can it contribute to East African development? Archived 23 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine Overseas Development Institute

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Anami, Luke (25 November 2024). "EAC@25: Broke bloc trudges on, celebrating trade wins". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b Anami, Luke (6 July 2024). "Somalia pays $7.8m towards EAC budget". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Anami, Luke (30 June 2024). "EAC members to fund bulk of bloc's $112m budget". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Anami, Luke (8 June 2024). "Nduva hits the ground running, but she has a full in-tray at EAC headquarters". Daily Nation. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Onyango-Obbo, Charles (8 June 2024). "Here's how to deal with EAC's defaulters, DR Congo, South Sudan and Burundi". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Anami, Luke (30 November 2024). "Why EAC presidents prefer Ruto to Tshisekedi as chair". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Instability in the Democratic Republic of Congo". Global Conflict Tracker. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d "M23 rebels in DR Congo deny shooting down UN helicopter". BBC. 30 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ a b Martina Schwikowski (8 April 2022). "M23 rebels resurface in DR Congo". DW. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Paul Kagame, War Criminal?". Newsweek. 14 January 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Subcommittee Hearing: Developments in Rwanda - Committee on Foreign Affairs". Committee on Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 15 July 2017. http://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA16/20150520/103498/HHRG-114-FA16-Transcript-20150520.pdf p. 74

- ^ a b c Simone Schlindwein (30 March 2022). "Neue Kämpfe im Osten Kongos: UN-Blauhelme sterben". taz (in German). Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "DR Congo: UN condemns M23 rebel attacks on peacekeeping force in North Kivu". Africa News. 23 May 2022. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Easing the Turmoil in the Eastern DR Congo and Great Lakes" (PDF). Crisis Group Africa Briefing (181). Nairobi, Brussels: International Crisis Group. 25 May 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Rwanda Inside DRC, Aiding M23 - Report". VOA. 4 August 2022. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Al-Hadji Kudra Maliro; Justin Kabumba (13 June 2022). "Congo military accuses Rwanda of invasion; rebels seize town". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Djaffar Sabiti (13 June 2022). "Congo rebels seize eastern border town, local activists say". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Robert Muhereza (17 June 2022). "Fresh fighting erupts in Bunagana". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Kenya calls for immediate deployment of regional force to eastern Congo". Reuters. 16 June 2022. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "DR Congo agrees to EAC force deployment without Rwandan army". The EastAfrican. 19 June 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Museveni in Kenya for EAC meeting to discuss DR Congo conflict". Daily Monitor. 20 June 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Andrew Bagala (21 June 2022). "EAC leaders order M23 rebels out of Bunagana". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Andrew Bagala; Robert Muhereza (22 June 2022). "Congo-M23 ceasefire fails". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Kenya to deploy army to eastern DRC to fight M23 rebels". news24. 2 November 2022. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Uganda Readies Strike Force to Counter M23 Rebels". Chimp Reports. 17 November 2022. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "South Sudan Sends 750 Troops to DRC". VOA. 28 December 2022. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Rebels Pull Back in Eastern DR Congo as Regional Force Deploys". VOA. 17 March 2023. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2023.