Location of Earth

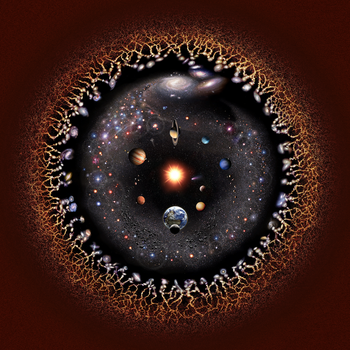

Logarithmic representation of the universe centered on the Solar System. Celestial bodies on this graphic are clickable |

Knowledge of the location of Earth has been shaped by 400 years of telescopic observations, and has expanded radically since the start of the 20th century. Initially, Earth was believed to be the center of the Universe, which consisted only of those planets visible with the naked eye and an outlying sphere of fixed stars.[1] After the acceptance of the heliocentric model in the 17th century, observations by William Herschel and others showed that the Sun lay within a vast, disc-shaped galaxy of stars.[2] By the 20th century, observations of spiral nebulae revealed that the Milky Way galaxy was one of billions in an expanding universe,[3][4] grouped into clusters and superclusters. By the end of the 20th century, the overall structure of the visible universe was becoming clearer, with superclusters forming into a vast web of filaments and voids.[5] Superclusters, filaments and voids are the largest coherent structures in the Universe that we can observe.[6] At still larger scales (over 1000 megaparsecs[a]) the Universe becomes homogeneous, meaning that all its parts have on average the same density, composition and structure.[7]

Since there is believed to be no "center" or "edge" of the Universe, there is no particular reference point with which to plot the overall location of the Earth in the universe.[8] Because the observable universe is defined as that region of the Universe visible to terrestrial observers, Earth is, because of the constancy of the speed of light, the center of Earth's observable universe. Reference can be made to the Earth's position with respect to specific structures, which exist at various scales. It is still undetermined whether the Universe is infinite. There have been numerous hypotheses that the known universe may be only one such example within a higher multiverse; however, no direct evidence of any sort of multiverse has been observed, and some have argued that the hypothesis is not falsifiable.[9][10]

Details

[edit]Earth is the third planet from the Sun with an approximate distance of 149.6 million kilometres (93.0 million miles), and is traveling nearly 2.1 million kilometres per hour (1.3 million miles per hour) through outer space.[11]

Table

[edit]| Feature | Diameter | Notes | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (most suitable unit) | (km, with scientific notation) | |||

| Earth | 12,756.2 km (equatorial) |

1.28×104 | Measurement comprises just the solid part of the Earth; there is no agreed upper boundary for Earth's atmosphere. The geocorona, a layer of UV-luminescent hydrogen atoms, lies at 100,000 km. The Kármán line, defined as the boundary of space for astronautics, lies at 100 km. |

[12][13][14][15] |

| Orbit of the Moon | 768,210 km[b] | 7.68×105 | The average diameter of the orbit of the Moon relative to the Earth. | [16] |

| Geospace | 6,363,000–12,663,000 km (110–210 Earth radii) |

6.36×106–1.27×107 | The space dominated by Earth's magnetic field and its magnetotail, shaped by the solar wind. | [17] |

| Earth's orbit | 299.2 million km[b] 2 AU[c] |

2.99×108 | The average diameter of the orbit of the Earth relative to the Sun. Encompasses the Sun, Mercury and Venus. |

[18] |

| Inner Solar System | ~6.54 AU | 9.78×108 | Encompasses the Sun, the inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars) and the asteroid belt. Cited distance is the 2:1 resonance with Jupiter, which marks the outer limit of the asteroid belt. |

[19][20][21] |

| Outer Solar System | 60.14 AU | 9.00×109 | Includes the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune). Cited distance is the orbital diameter of Neptune. |

[22] |

| Kuiper belt | ~96 AU | 1.44×1010 | Belt of icy objects surrounding the outer Solar System. Encompasses the dwarf planets Pluto, Haumea and Makemake. Cited distance is the 2:1 resonance with Neptune, generally regarded as the outer edge of the main Kuiper belt. |

[23] |

| Heliosphere | 160 AU | 2.39×1010 | Maximum extent of the solar wind and the interplanetary medium. | [24][25] |

| Scattered disc | 195.3 AU | 2.92×1010 | Region of sparsely scattered icy objects surrounding the Kuiper belt. Encompasses the dwarf planet Eris. Cited distance is derived by doubling the aphelion of Eris, the farthest known scattered disc object. As of now, Eris's aphelion marks the farthest known point in the scattered disc. |

[26] |

| Oort cloud | 100,000–200,000 AU 0.613–1.23 pc[a] |

1.89×1013–3.80×1013 | Spherical shell of over a trillion (1012) comets. Existence is currently hypothetical, but inferred from the orbits of long-period comets. | [27] |

| Solar System | 1.23 pc | 3.80×1013 | The Sun and its planetary system. Cited diameter is that of the Sun's Hill sphere; the region of its gravitational influence. | [28] |

| Local Interstellar Cloud | 9.2 pc | 2.84×1014 | Interstellar cloud of gas through which the Sun and a number of other stars are currently travelling. | [29] |

| Local Bubble | 2.82–250 pc | 8.70×1013–7.71×1015 | Cavity in the interstellar medium in which the Sun and a number of other stars are currently travelling. Caused by a past supernova. |

[30][31] |

| Gould Belt | 1,000 pc | 3.09×1016 | Projection effect of the Radcliffe wave and Split linear structures (Gould Belt),[32] between which the Sun is currently travelling. | [33] |

| Orion Arm | 3000 pc (length) |

9.26×1016 | The spiral arm of the Milky Way Galaxy through which the Sun is currently travelling. |

|

| Orbit of the Solar System | 17,200 pc | 5.31×1017 | The average diameter of the orbit of the Solar System relative to the Galactic Center. The Sun's orbital radius is roughly 8,600 parsecs, or slightly over halfway to the galactic edge. One orbital period of the Solar System lasts between 225 and 250 million years. |

[34][35] |

| Milky Way Galaxy | 30,000 pc | 9.26×1017 | Our home galaxy, composed of 200 billion to 400 billion stars and filled with the interstellar medium. | [36][37] |

| Milky Way subgroup | 840,500 pc | 2.59×1019 | The Milky Way and those satellite dwarf galaxies gravitationally bound to it. Examples include the Sagittarius Dwarf, the Ursa Minor Dwarf and the Canis Major Dwarf. Cited distance is the orbital diameter of the Leo T Dwarf galaxy, the most distant galaxy in the Milky Way subgroup. Currently 59 satellite galaxies are part of the subgroup. |

[38] |

| Local Group | 3 Mpc[a] | 9.26×1019 | Group of at least 80 galaxies of which the Milky Way is a part. Dominated by Andromeda (the largest), the Milky Way and Triangulum; the remainder are dwarf galaxies. |

[39] |

| Local Sheet | 7 Mpc | 2.16×1020 | Group of galaxies including the Local Group moving at the same relative velocity towards the Virgo Cluster and away from the Local Void. | [40][41] |

| Virgo Supercluster | 30 Mpc | 9.26×1020 | The supercluster of which the Local Group is a part. It comprises roughly 100 galaxy groups and clusters, centred on the Virgo Cluster. The Local Group is located on the outer edge of the Virgo Supercluster. |

[42][43] |

| Laniakea Supercluster | 160 Mpc | 4.94×1021 | A group connected with the superclusters of which the Local Group is a part. Comprises roughly 300 to 500 galaxy groups and clusters, centred on the Great Attractor in the Hydra–Centaurus Supercluster. |

[44][45][46][47] |

| Pisces–Cetus Supercluster Complex | 330 Mpc | 1×1022 | Galaxy filament that includes the Pisces-Cetus Superclusters, Perseus–Pisces Supercluster, Sculptor Supercluster and associated smaller filamentary chains. | [48][49] |

| Observable Universe | 28,500 Mpc | 8.79×1023 | At least 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe, arranged in millions of superclusters, galactic filaments, and voids, creating a foam-like superstructure. | [50][51][52][53] |

| Universe | Minimum 28,500 Mpc (possibly infinite) |

Minimum 8.79×1023 | Beyond the observable universe lie the unobservable regions from which no light has yet reached the Earth. No information is available, as light is the fastest travelling medium of information. However, uniformitarianism argues that the Universe is likely to contain more galaxies in the same foam-like superstructure. |

[54] |

Gallery

[edit]

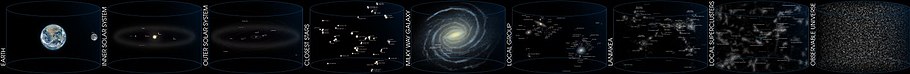

Clickable image of the Location of Earth. Place your mouse cursor over an area in the image to see the related area name; click to link to an article about the area.

Clickable image of the Location of Earth. Place your mouse cursor over an area in the image to see the related area name; click to link to an article about the area.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c A parsec (pc) is the distance at which a star's parallax as viewed from Earth is equal to one second of arc, equal to roughly 206,000 AU or 3.0857×1013 km. One megaparsec (Mpc) is equivalent to one million parsecs.

- ^ a b Semi-major and semi-minor axes.

- ^ 1 AU or astronomical unit is the distance between the Earth and the Sun, or 150 million km. Earth's orbital diameter is twice its orbital radius, or 2 AU.

References

[edit]- ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Harvard University Press. pp. 5–20. ISBN 978-0-674-17103-9.

- ^ "1781: William Herschel Reveals the Shape of our Galaxy". Carnegie Institution for Science. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "The Spiral Nebulae and the Great Debate". Eberly College of Science. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "1929: Edwin Hubble Discovers the Universe is Expanding". Carnegie Institution for Science. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "1989: Margaret Geller and John Huchra Map the Universe". Carnegie Institution for Science. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Villanueva, John Carl (2009). "Structure of the Universe". Universe Today. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Kirshner, Robert P. (2002). The Extravagant Universe: Exploding Stars, Dark Energy and the Accelerating Cosmos. Princeton University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-691-05862-7.

- ^ Mainzer, Klaus; Eisinger, J. (2002). The Little Book of Time. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-387-95288-8.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (2012). "5 Reasons We May Live in a Multiverse". space.com. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Kragh, H. (2009). "Contemporary History of Cosmology and the Controversy over the Multiverse". Annals of Science. 66 (4): 529–551. doi:10.1080/00033790903047725. S2CID 144773289.

- ^ Fraknoi, Andrew (2007). "How Fast Are You Moving When You Are Sitting Still?" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

NOTE: Estimated velocity of the Earth traveling through outer space may be between 1.3–3.1 million kilometres per hour (0.8–1.9 million miles per hour) – see discussion at "Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2019 July 20#How fast are we moving through space?" - ^ "Selected Astronomical Constants, 2011". The Astronomical Almanac. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ World Geodetic System (WGS-84). Available online from National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Exosphere – overview". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. 2011. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ S. Sanz Fernández de Córdoba (24 June 2004). "The 100 km Boundary for Astronautics". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011.

- ^ NASA Moon Factsheet and NASA Solar System Exploration Moon Factsheet NASA Retrieved on 17 November 2008

- ^ Koskinen, Hannu (2010), Physics of Space Storms: From the Surface of the Sun to the Earth, Environmental Sciences Series, Springer, ISBN 978-3-642-00310-3

- ^ "Earth Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 17 November 2008. and "Earth: Facts & Figures". Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Petit, J.-M.; Morbidelli, A.; Chambers, J. (2001). "The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt" (PDF). Icarus. 153 (2): 338–347. Bibcode:2001Icar..153..338P. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Roig, F.; Nesvorný, D. & Ferraz-Mello, S. (2002). "Asteroids in the 2 : 1 resonance with Jupiter: dynamics and size distribution". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 335 (2): 417–431. Bibcode:2002MNRAS.335..417R. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05635.x.

- ^ Brož, M; Vokrouhlický, D; Roig, F; Nesvorný, D; Bottke, W. F; Morbidelli, A (2005). "Yarkovsky origin of the unstable asteroids in the 2/1 mean motionresonance with Jupiter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 359 (4): 1437–1455. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.359.1437B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08995.x.

- ^ NASA Neptune factsheet and NASA Solar System Exploration Neptune Factsheet NASA Retrieved on 17 November 2008

- ^ De Sanctis, M. C; Capria, M. T; Coradini, A (2001). "Thermal Evolution and Differentiation of Edgeworth–Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astronomical Journal. 121 (5): 2792–2799. Bibcode:2001AJ....121.2792D. doi:10.1086/320385.

- ^ NASA/JPL (2009). "Cassini's Big Sky: The View from the Center of Our Solar System". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ Fahr, H. J.; Kausch, T.; Scherer, H. (2000). "A 5-fluid hydrodynamic approach to model the Solar System-interstellar medium interaction" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 357: 268. Bibcode:2000A&A...357..268F. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2009. See Figures 1 and 2.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 136199 Eris (2003 UB313)" (2008-10-04 last obs). Retrieved 21 January 2009.

- ^ Morbidelli, Alessandro (2005). "Origin and dynamical evolution of comets and their reservoir". arXiv:astro-ph/0512256.

- ^ Littmann, Mark (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-0-486-43602-9.

- ^ Mark Anderson, "Don't stop till you get to the Fluff", New Scientist no. 2585, 6 January 2007, pp. 26–30

- ^ Seifr, D.M. (1999). "Mapping the Countours of the Local Bubble". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 346: 785–797. Bibcode:1999A&A...346..785S.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (2014). "Evidence for Supernovas Near Earth". NASA.

- ^ Alves, João; Zucker, Catherine; Goodman, Alyssa A.; Speagle, Joshua S.; Meingast, Stefan; Robitaille, Thomas; Finkbeiner, Douglas P.; Schlafly, Edward F.; Green, Gregory M. (23 January 2020). "A Galactic-scale gas wave in the Solar Neighborhood". Nature. 578 (7794): 237–239. arXiv:2001.08748v1. Bibcode:2020Natur.578..237A. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1874-z. PMID 31910431. S2CID 256822920.

- ^ Popov, S. B; Colpi, M; Prokhorov, M. E; Treves, A; Turolla, R (2003). "Young isolated neutron stars from the Gould Belt". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 406 (1): 111–117. arXiv:astro-ph/0304141. Bibcode:2003A&A...406..111P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030680. S2CID 16094637.

- ^ Eisenhauer, F.; Schoedel, R.; Genzel, R.; Ott, T.; Tecza, M.; Abuter, R.; Eckart, A.; Alexander, T. (2003). "A Geometric Determination of the Distance to the Galactic Center". Astrophysical Journal. 597 (2): L121 – L124. arXiv:astro-ph/0306220. Bibcode:2003ApJ...597L.121E. doi:10.1086/380188. S2CID 16425333.

- ^ Leong, Stacy (2002). "Period of the Sun's Orbit around the Galaxy (Cosmic Year)". The Physics Factbook.

- ^ Christian, Eric; Samar, Safi-Harb. "How large is the Milky Way?". NASA. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ^ Frommert, H.; Kronberg, C. (25 August 2005). "The Milky Way Galaxy". SEDS. Archived from the original on 12 May 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ Irwin, V.; Belokurov, V.; Evans, N. W.; et al. (2007). "Discovery of an Unusual Dwarf Galaxy in the Outskirts of the Milky Way". The Astrophysical Journal. 656 (1): L13 – L16. arXiv:astro-ph/0701154. Bibcode:2007ApJ...656L..13I. doi:10.1086/512183. S2CID 18742260.

- ^ "The Local Group of Galaxies". University of Arizona. Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Tully, R. Brent; Shaya, Edward J.; Karachentsev, Igor D.; Courtois, Hélène M.; Kocevski, Dale D.; Rizzi, Luca; Peel, Alan (March 2008). "Our Peculiar Motion Away from the Local Void". The Astrophysical Journal. 676 (1): 184–205. arXiv:0705.4139. Bibcode:2008ApJ...676..184T. doi:10.1086/527428. S2CID 14738309.

- ^ Tully, R. Brent (May 2008). "The Local Void is Really Empty". Dark Galaxies and Lost Baryons, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, IAU Symposium. Vol. 244. pp. 146–151. arXiv:0708.0864. Bibcode:2008IAUS..244..146T. doi:10.1017/S1743921307013932. S2CID 119643726.

- ^ Tully, R. Brent (1982). "The Local Supercluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 257: 389–422. Bibcode:1982ApJ...257..389T. doi:10.1086/159999.

- ^ "Galaxies, Clusters, and Superclusters". NOVA Online. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Newly identified galactic supercluster is home to the Milky Way". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. ScienceDaily. 3 September 2014.

- ^ Klotz, Irene (3 September 2014). "New map shows Milky Way lives in Laniakea galaxy complex". Reuters. ScienceDaily.

- ^ Gibney, Elizabeth (3 September 2014). "Earth's new address: 'Solar System, Milky Way, Laniakea'". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.15819. S2CID 124323774.

- ^ Carlisle, Camille M. (3 September 2014). "Laniakea: Our Home Supercluster". Sky and Telescope.

- ^ Tully, R. B. (1 April 1986). "Alignment of clusters and galaxies on scales up to 0.1 C". The Astrophysical Journal. 303: 25–38. Bibcode:1986ApJ...303...25T. doi:10.1086/164049.

- ^ Tully, R. Brent (1 December 1987). "More about clustering on a scale of 0.1 C". The Astrophysical Journal. 323: 1–18. Bibcode:1987ApJ...323....1T. doi:10.1086/165803.

- ^ Mackie, Glen (1 February 2002). "To see the Universe in a Grain of Taranaki Sand". Swinburne University. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ Lineweaver, Charles; Davis, Tamara M. (2005). "Misconceptions about the Big Bang". Scientific American. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Conselice, Christopher J.; Wilkinson, Aaron; Duncan, Kenneth; Mortlock, Alice (13 October 2016). "The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and its Implications". The Astrophysical Journal. 830 (2): 83. arXiv:1607.03909. Bibcode:2016ApJ...830...83C. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/830/2/83. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 17424588.

- ^ "Two Trillion Galaxies, at the Very Least". The New York Times. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Margalef-Bentabol, Berta; Margalef-Bentabol, Juan; Cepa, Jordi (February 2013). "Evolution of the cosmological horizons in a universe with countably infinitely many state equations". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 015. 2013 (2): 015. arXiv:1302.2186. Bibcode:2013JCAP...02..015M. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2013/02/015. S2CID 119614479.