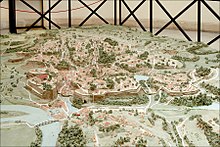

Plan of Rome (Bigot)

| Plan of Rome | |

|---|---|

Map of Rome, Circus maximus and Colosseum area, based on Paul Bigot's plan on display at Caen University. | |

| Artist | Paul Bigot |

| Year | 1900-1942 |

| Dimensions | 600 cm × 1,100 cm (240 in × 430 in) |

| Designation | French historical monument |

| Location | University of Caen, Caen (France) Art & History Museum, Brussels, (Belgium) |

The Plan of Rome is a model, more precisely a relief map, of ancient Rome in the 4th century. Made of varnished plaster (11 × 6 m), it represents three-fifths of the city at a 1/400 scale, forming a puzzle of around one hundred pieces. It was created by Paul Bigot, an architect and winner of the Grand Prix de Rome in 1900. Initially focused on the Circus Maximus, Bigot's work gradually expanded to cover an area of over 70 m2. It has also become a virtual reconstruction project led by the University of Caen since the 1990s.

Bigot developed the model as a synthesis of the literary, archaeological, and iconographic knowledge available at the beginning of the 20th century, working on it for four decades. His project followed the tradition of the "Rome submissions," where residents of the Villa Medici presented reconstructions of architectural elements of ancient Rome. It also coincided with the profound renewal of knowledge about the city during major works accompanying its transformation into the capital of modern Italy. The Plan of Rome quickly gained recognition as both an artistic masterpiece and a valuable educational tool, with various international events showcasing it to the public.

Following drawings and watercolors, reconstructions of ancient Rome took the form of models in the 20th century. From the late 20th century and early 21st century, with advances in computer technology, reconstructions have increasingly relied on virtual reality. Bigot created four plaster models before his death in 1942, only two of which remained in the early 21st century—one in Caen and the other in Brussels. The Caen model, classified as a historic monument in 1978, has been the focus of dedicated work since the mid-1990s to create a virtual counterpart accessible to the public, integrating current knowledge about ancient Rome's topography. This project saw significant acceleration during the 2010s.

The most recent work, using advanced techniques and the virtual model, does not overshadow Bigot's monumental efforts, which remain a testament to early 20th-century knowledge about Rome. Bigot remains a pioneer in the topography of Rome, as well as in ancient architecture and urban planning. His work retains a certain prestige in the early 21st century, even beyond its archaeological accuracy. The virtual model, on the other hand, can evolve with new archaeological discoveries and advances in technology, enabling ongoing updates to the project.

History

[edit]A "Rome Submission" reflecting interest in ancient topography

[edit]Rome Grand Prix in 1900

[edit]

Paul Bigot was a Normandy-born architect from Orbec[1] and the brother of animal painter and sculptor Raymond Bigot (1872-1953). He won the Grand Prix de Rome in architecture in 1900 with his proposal for A Thermal Bath and Casino Establishment (including baths, a hotel, and a casino[2]). His work made a strong impression, showcasing a coherent ensemble with distinctly differentiated elements.[3] The competition granted access to training at the French Academy in Rome.[4]

Upon arriving in Italy, Bigot developed a passion for ancient Rome, which was still largely hidden beneath the modern city. He became so involved in excavations that he spent more time at the French School than at the Villa Medici. At the Villa, he encountered Tony Garnier,[5] who in 1901 submitted a provocative project[6] for an Industrial City,[7] described as a "manifesto for modern urbanism,"[8] which sparked numerous reactions. The idea of creating a model to represent a structure within its environment[9] reportedly emerged from a discussion among residents, all of whom were architects,[10] that same year.[3]

The school imposed a mandatory exercise for architects to evaluate their skills and progress:[11] the final-year "Rome submission." This traditionally involved a watercolor reconstruction or restoration of an ancient monument, accompanied by contemporary surveys of buildings[12][13]—a practice dating back to 1778.[14] These works helped preserve the state of ancient buildings during the 18th and 19th centuries.[15] Restoration focused on ruins and sought plausibility, while reconstruction aimed to reproduce the ancient state of a structure. Both approaches raised the question of "the relationship between representation and the reality of the depicted object."[16] Bigot began his work with submissions similar to those of his peers.[17] In 1902, he signed a petition advocating for greater freedom in the submissions for Villa Medici residents.[3]

Bigot chose to work on a disappeared structure in a densely built area.[18] His third-year submission[19] in 1903 was a reconstruction of the Circus Maximus,[20] which at the time was covered by a gasworks plant. In 1905, he submitted a board titled Research on the Boundaries of the Grand Circus, attempting a plausible reconstruction of a monument that was "almost entirely disappeared." This reconstruction was still considered plausible even at the end of the 20th century despite certain "risky" elements.[21] To support his hypotheses, Bigot conducted archaeological excavations funded by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres,[22] publishing the results and drawing analogies with other structures, such as the Circus of Maxentius.[22] He also produced detailed reports to bolster his funding requests[3] for this costly project.[22] He secured a grant of 5,000 francs from the Académie in 1908,[23] along with private and public funding, including 25,000 francs from the French government in 1909 in exchange for a promise to donate the model to the Sorbonne.[24]

At this point, he decided to create an architectural model, and his Circus Maximus was submitted in 1908. The enthusiastic reception of this initial work, regarded from the start as "an impressive piece for the vivid image it provides of the ancient city,"[22] encouraged him to embark on a project that would ultimately occupy 40 years of his life.[9] Bigot’s prolonged stay in Rome perplexed figures like Eugène Guillaume and the Académie des Beaux-Arts due to the project's costs.[25] However, he disregarded their comments, bolstered by support from Louis Duchesne,[12] the director of the French School of Rome.[26]

He formed connections with prominent experts in Roman topography, including Christian Hülsen and Rodolfo Lanciani.[27][28][19]

To his masters' surprise, Bigot first proposed a clay model of the Circus Maximus. To convey the building's scale, he then modeled the surrounding district, the city center, and eventually most of Rome[29] (excluding the Baths of Diocletian and the Vatican) with a visionary approach that might no longer be evident today. By 1906, he had obtained subsidies to complete his work and was in Rome in 1907-1908 to prepare for the 1911 exhibition.[20] By 1909, he had the idea of creating a bronze model.[30]

Bigot's stay in Rome extended to seven years.[7] According to Jérôme Carcopino, Bigot "infinitely delayed his departure for Paris, fearing that an error or omission would betray the fidelity of his model."[31] Carcopino also remarked that "while promotions came and went, Bigot remained, eyes fixed on his plan, unwaveringly faithful to his dream."[32] Ultimately, he spent eleven years in Rome, living on scholarships[33] before returning to France in 1912.[34]

Continuing a tradition

[edit]

Bigot's model took the form of a relief plan. This technique had been developed extensively in France from 1668 under the initiative of Louis XIV's minister Louvois, primarily for military purposes, representing the kingdom’s major fortified places at a scale of 1/600.[15] Two years earlier, Jean-Baptiste Colbert had founded the French Academy in Rome to "help artists draw inspiration from Roman models."[35]

Bigot's work continued a long tradition of reconstructing the ancient city, beginning with Flavio Biondo's Roma Instaurata in 1446, followed by Pirro Ligorio in the 16th century, Giovan Battista Nolli in 1748,[36] and Luigi Canina in the first half of the 19th century.[37]

The first modern models of Rome appeared at the end of the 18th century, made of cork or plaster,[38][39] intended for wealthy tourists or collectors like Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel and Louis-François Cassas.[40] Notably, they included a 3-meter-long Colosseum and a Pantheon displayed at the Johannisburg Castle.[41] A partial relief model of Rome was made between 1850 and 1853 for military purposes following the siege of the city. This model realistically depicted ancient monuments as part of the backdrop for events,[42] though they were not its primary focus.

From 1860, scholarship recipients were divided between scientific ambitions and a desire for freedom from the Académie des Beaux-Arts' strict rules requiring depictions of the current state and a restored version of a monument.[43] The inclusion of "atmospheric reconstructions" as annexes to their submissions allowed architects to break free and present realistic scenes, which were popular at the time, inspired by artists like Théodore Chassériau, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.[44]

Paul Bigot belongs to the "tradition of architect-archaeologists,"[45] and his work stands at the crossroads of the envois de Rome from the 19th and 20th centuries, situated between studies of monument complexes and those focused on colonial cities such as Selinunte, Priene, or Pompeii.[20] These studies of ancient newly planned cities are considered "one of the sources of modern urban planning."[46] His plan aligns with the envois tradition aimed at presenting "a complete image of a monument or site," including representations of the city, buildings, and dwellings.[47] The envois of this period focused on sanctuaries, thermal complexes, small towns, palaces, villas, or neighborhoods.[48] Architects became increasingly interested in the urban fabric, as this era also marked the birth of urbanism.[49] For the residents of the Villa Medici, their Roman stay was a "rediscovery of planned urbanism," distinguishing between two types of cities: newly founded ones and those "shaped by the slow work of time."[50]

Period of archaeological and urbanistic effervescence in Rome

[edit]They were also part of a movement of interest in the history and archaeology of ancient Rome, which followed the city's transformation into the capital of Italy after 1870[51] and the large-scale projects undertaken to make it the capital of a modern country.[52] These infrastructure works isolated the ancient city from the developing suburbs.[53] This period marked the "historical and archaeological rediscovery of the ancient city."[54] It was no longer seen as a romantic vision of a city in ruins[55] but rather as one threatened by "banal modernity."[56] Ancient monuments became "symbols of patriotic grandeur."[57] Urban planning debates emerged to beautify the new Italian capital, continuing the tradition of ancient urban design concepts.[58]

This period also saw significant contributions from Rodolfo Lanciani, who published numerous popular works in French and English,[54] as well as the more scientific Forma Urbis, a "turning point in Roman cartography,"[59] from 1893 to 1901. Discovered behind the Forum of Peace,[60] the Forma Urbis continued to be studied and published into the late 20th century.[61] Created under Emperor Septimius Severus, the Forma Urbis was a marble map of Rome at a 1:240 scale, dating back to the 3rd century. Only about 15%[19] (1,019 fragments) have survived. Additional lost fragments, known through sketches, remain valuable for research.[62] The Severan map, preserved at the Capitoline Museum, became the subject of studies and debates at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.[19] Despite acknowledged errors, Lanciani's 1:1000 publication of the Severan map remained a fundamental source for understanding vanished or poorly documented monuments.[28] Between 1898 and 1914, a preserved space known as the Passeggiata Archeologica was created.[59]

Giuseppe Marcelliani created a terracotta model of Rome at a 1/100 scale around 1904,[63] continuing until 1910.[64] He prioritized "the aesthetic and monumental aspects,"[65] presenting "a succession of monumental complexes."[66] Marcelliani's approach differed, with some buildings treated "as blocks" and others designed through assembly. Overall, approximations were noted in the representations of monument complexes.[67] His work, focused on the monumental center,[68] was highly successful and circulated through postcards.[64] It was exhibited until 1923 with an entry fee[69] and was in poor condition by the early 21st century, although partially displayed.[70]

Interest in ancient Rome with ideological objectives reached its peak between 1911 and 1937, shared by both the Italian monarchy and the fascist government,[71] as part of a "political reclamation of the image of Rome and its empire."[72] Mussolini, by promoting Romanità, sought to bolster his legitimacy.[73] However, Mussolini's urban planning projects devastated archaeological remains.[74] Bigot could not be suspected of adhering to these ideologies,[75] as he was a pacifist and a supporter of Aristide Briand.[76]

Paul Bigot served as an aviation observer during World War I and, after the conflict, participated in the reconstruction of war-torn towns in northern and eastern France.[34] Working both on-site and in his Parisian workshop near a dome of the Grand Palais,[77] he created a masterpiece of miniaturism and precision, which he continued to modify throughout his life.[78] He made one final trip to Rome in 1934,[79] supported by a new subsidy,[78] to stay informed about recent discoveries related to major projects undertaken in the 1930s, particularly the construction of the Via dei Fori Imperiali, inaugurated on April 9, 1932, between the forums of Caesar and Augustus. He also studied developments at Largo Argentina (1926-1932), the Theatre of Marcellus, the Mausoleum of Augustus, and the Ara Pacis.[80] The war complicated access to the latest information on these projects.[81]

Brief history of the different versions of the plan of Rome until the execution of Bigot’s will

[edit]Immediate success

[edit]

Bigot's work had "significant resonance"[35] and was considered "a revelation."[82] Its success was immediate, with its "artistic, educational, and scientific value" recognized right away,[37] garnering press attention.[20] In 1911, the architect exhibited his model at the Mostra archeologica at the Baths of Diocletian, which celebrated the 50th anniversary of the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy on March 17, 1861.[71] The exhibition included casts of Roman works from various regions of the Roman Empire.[75] Bigot's model, covering 50 square meters at the time,[83] was displayed in a room named after him,[84] an "exceptional tribute"[85] (the current "Planetario Room"[86]). The organizers recommended that visitors make a point of seeing this room, warning that otherwise, they would gain only "an incomplete idea of the exhibition itself."[24] Bigot later described this first version of the Plan of Rome as "quite rough."[1] The exhibition also featured casts of works from across the Empire's territories,[87] aiming to express "the revival of national unity, rediscovered through an ancient community of origins."[88]

Bigot received the Medal of Honor at the 1913 Salon d'Architecture of French Artists.[89] Forced to leave the space loaned by the Italian government, the model was installed at the Grand Palais on April 15, under the glass roof, which became his workshop until his death,[24] where a version of his model was placed on the fourth floor.[90] That same year, he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor.[82] Monsignor Duchesne proposed transforming the plan into metal.[91] Georges Clemenceau had a law passed unanimously[24] to fund the creation of the plan in bronze, with a subsidy of 80,000 francs. However, the outbreak of World War I halted the project.[77] Clemenceau and Le Figaro launched a subscription campaign, but the war and Bigot's meticulous nature interrupted the endeavor.[82]

After World War I, Bigot received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation to complete his work and produce two additional copies, one for the University of Pennsylvania and the other for the Sorbonne.[92] The bronze plan project resumed between 1923 and 1925.[91][24] In 1925, Bigot became a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, and in 1931, he was inducted into the Institut de France[1] as a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, taking Henri Deglane's seat. As such, he participated in selecting the Prix de Rome winners and managing submissions.[93][94]

A lifelong endeavor

[edit]Throughout his life, for over forty years,[89] Bigot’s passion was updating his model. As a result, the only two surviving versions — the monochromatic Caen plan, which was his original working model,[37] and the colored version at the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels — are slightly different.

Bigot's renown lasted until World War II. The French government commissioned a copy for the Sorbonne, and the United States requested one for the University of Philadelphia. The model underwent numerous modifications, especially in 1937,[94] the year marking the commemoration of the bimillennium of Augustus' birth,[71] although the details of many updates remain unknown.[95] The version presented at the 1937 Universal Exposition was described as "the final version of P. Bigot’s relief." That same year, the Il Plastico model by Gismondi was exhibited in Rome[79] at the Mostra Augustea della Romanità, a show initiated by art historian and fascist party deputy Giulio Quirino Giglioli.[85] The exhibition was a critical and public success[96] and represented "the apotheosis of the fascist regime as the heir to Rome."[88] Another exhibition dedicated to the regime opened on the same day as the one on Antiquity.[97]

Appointed a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1923 and head of a studio two years later,[24] Bigot, who was also the architect for French historical buildings, collaborated with the Christofle silversmith company to create a bronze casting of the Plan of Rome. However, the project remained incomplete due to the author's perfectionism, as he constantly revised it based on archaeological discoveries. In 1933, the Rector of the Paris Academy granted him 150,000 francs to continue work on the plan.[98] In 1937, a version of the Plan of Rome was presented at the Universal Exposition at the Palais de Chaillot,[1][94] either the Caen or Brussels version.[99] Bigot also designed the exposition's main gate at Place de la Concorde.[7]

André Piganiol provided some assistance with the updates a few years before Bigot's death.[100] The last modifications to the relief occurred between 1937 and 1942.[101] The meticulous updating of the plan made it "the visual expression of ongoing archaeological research."[102] The war hindered the flow of information in the late 1930s and early 1940s.[31] Bigot passed away unexpectedly on June 8, 1942,[45] while still working on the bronze plan.[1] In addition to updating his model, he was also designing monumental architectural projects.[103]

According to François Hinard, Bigot relied on his disciples, Henry Bernard, a future key figure in the reconstruction of Caen, and Paul-Jacques Grillo, to continue updating the plan[104] and "complete and continue the changes interrupted by the declaration of war."[105] Bigot's wish to have his work updated after World War II and his death was never fulfilled. Upon returning from captivity in Germany, Henry Bernard found two complete models in the Grand Palais rotunda,[92] one of which was donated to the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels and the other to the University of Caen.[77] The donation to the Norman University was contingent upon the allocation of a specific space under the large amphitheaters of the law and literature faculties, which was accepted by deans Yver, Musset, and de Boüard.[106]

Versions of the relief plan from Bigot's death to the present

[edit]There are four known versions of Bigot's plaster plan, two of which have disappeared. A fifth version, partially made of bronze, was only partially completed. The two preserved versions have "noticeably different appearances due to differences in plaster treatment."[45]

The Plan of Rome at the University of Caen

[edit]Characteristics, preservation, and neglect

[edit]

The Caen model is monochromatic,[108] with the plaster "tinted and waxed"[109] in ochre, giving the city "a homogeneous color reminiscent of its appearance at sunset."[45] Paul Bigot designed a lighting system for the model, using precisely positioned projectors[110] fitted with colored lenses. This system aimed to reproduce the natural lighting of the city.[111][112]

According to Paola Ciancio-Rossetto, the plan preserved at the University of Caen is the one from the 1937 Universal Exposition[99][113] and is the most up-to-date surviving version.[114] Royo,[103] Fleury, and Madeleine believe it to be the original model belonging to the architect,[37] whose updates ceased with his death.[108] The model, found in Bigot's workshop at the Grand Palais,[115] was donated to the University of Caen in 1956.[35]

Student and Legatee of Paul Bigot, Henry Bernard,[116] architect of the post-1945 reconstruction of the city and particularly of the University of Caen, stored the model at the University of Caen in a specially designed room in the basement of the Law building,[37] which was "almost fortified," according to Hinard.[117] This was done in agreement with Rector Pierre Daure and the university council.[77] An Association of Friends of the Plan of Rome was established. The installation, inaugurated on April 28, 1958,[108] included a sound and light show with illumination of the various monuments represented, along with explanations provided by Hellenist Henri Van Effenterre and historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet.[27] The explanations were presented by major sections,[118] "sector by sector."[119]

Even before 1968, the model fell into obscurity.[27] Its "long descent into oblivion" included the deterioration of the metal structure, theft, damage,[108] and the dismantling of the lighting system. Several small elements of the model were stolen during this period, including the Arch of Constantine,[120] the Meta Sudans,[121] the Colossus of Nero,[122] small temples (such as three from the sacred area of Largo di Torre Argentina), and equestrian statues originally represented by Bigot.

Rediscovery and restoration

[edit]The model was listed as a historic monument on June 12, 1978,[123] or in 1987,[124] as an object of historical importance, granting it legal protection against any modifications.

It took more than ten years to rediscover and restore the piece,[108] which had "come dangerously close to disaster."[47] François Hinard rediscovered the work after his appointment as a professor of Roman history in 1983 and raised public and official awareness, reactivating the Association of Friends of the Plan of Rome.[124] In 1987, part of the ceiling collapsed due to household water infiltration in the room,[108] damaging the model and reigniting interest in the piece. Élisabeth Deniaux devoted specific teaching to it.[125] A plan to move the model was initially considered but ultimately abandoned, and its preservation at the university was confirmed in 1991.[124]

Since 1995-1996, the model has been housed in the new Maison de la Recherche en Sciences Humaines (Campus 1),[126][107] whose construction began in 1993.[124] Bigot's work is now displayed on a rotating platform and features lighting and camera systems[5] as part of an exhibition dedicated to ancient Rome.[127] The 11-meter diameter rotating platform[128] is red, reminiscent of imperial purple.[124]

Before its installation, the model underwent significant restoration[37] in the workshop of Philippe Langot,[124] a conservator-restorer in Semur-en-Auxois. The model had been dirty, cracked, and affected by condensation.[129][107] Following the restoration, some fragments remained unattached, possibly from earlier work before the 1958 inauguration.[130]

The restoration marked a favorable period for highlighting Paul Bigot's work and "opening new research perspectives." The first symposium was held in 1991 under François Hinard's direction.[37] The virtual restitution project developed as Bigot's model found its permanent location.[131]

The Plan of Rome in Brussels

[edit]Origins and role in an architecture museum

[edit]

Bigot's work also made an impact in Belgium, as evidenced by the diploma awarded to him by the Royal Academy of Sciences, Letters, and Fine Arts in 1933. The model located in Brussels was donated by Henry Bernard to Henry Lacoste,[99] an excavator at Apamea,[132] who, starting in 1955, sought to establish an architecture museum in Brussels. The Plan of Rome at his disposal, a casting dated 1937 and exhibited at the Palais de Chaillot according to Royo, was modified by Bigot until his death[115] and intended solely for educational purposes.[133] This version comprises 98 elements[134] and measures 11 by 4 meters.[60]

The project to acquire a model dates back to February 1938, initiated by students from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels after a lecture given by Paul Bigot.[135] Postponed by World War II, it was realized through the execution of Bigot's testament and Henry Bernard's donation. The model was installed on July 1, 1950,[37] at the Cinquantenaire Museum under Henry Lacoste's leadership,[136] with the generous and enthusiastic support of students from the Academy.[137] The students provided Lacoste with the means to acquire the model and ensured its transport and assembly. According to Fleury, the model was delivered to the Cinquantenaire Museum in 1936.[35]

The Rome Room was envisioned by its promoter as the embryo of a space dedicated to architecture and urban planning,[138] intended to provide young architects and researchers with various resources: models, plans, surveys, and wash drawings. The presentation of the model emphasized the urban planning projects that have shaped the entire history of the city of Rome.[139] Panels focused on themes such as the city of Rome during the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, as well as specific topics (gates, urban networks, aqueducts, etc.), accompanied the model.[140][141] A slideshow was also featured.[142] Lacoste viewed the urban project of Rome as linked to two primary axes, and the plan served as a tool to illustrate these urban theories.[143]

The Brussels plan, "delivered white,"[45] was colored by students shortly before the 1950 inauguration[135][137] to "add realism to the theoretical and scientific vision."[144] The colors chosen by Henry Lacoste's students[111] gave the Brussels model a "lifelike impression" inspired by the hues of eternal Rome.[112][44]

Enhancement in the early 21st century

[edit]

From 1950 to 1976, visits were conducted by a guide who used a cane with a tip, which caused damage to the model. In the meantime, in 1966, the model was relocated[145] to a new wing of the museum. It underwent its first major restoration in 1976-1977, including repainting and a new exhibition layout. Visitors could view the model from a balcony situated 3.50 meters high and walk around it. In the early 1990s, a sophisticated lighting system was installed to highlight 80 buildings.[134] This presentation inspired the staging of the Caen model after its relocation to its new destination in the 1990s.[124]

The model serves as an educational tool for detailed presentations and for exhibitions aimed at the general public outside school hours. Documents on the buildings are projected simultaneously with their illumination on the model.[146] The model is no longer used as a teaching aid for urban planning, as Lacoste had intended.[147] Françoise Lecocq notes the presence of Astérix and Obélix figurines in the Grand Circus arena.[148] The model, which has been continuously exhibited and maintained since 1950, underwent renovation in 2003-2004 during the "From Pompeii to Rome" exhibition.[82]

The model, described as "one of the key elements of the classical antiquities section," underwent a thorough cleaning in October 2018. A photogrammetry project was planned for the end of 2018, followed by an eight-month restoration period. The restoration of the sound and light system, including upgrades to the lighting, projections, and integration of new technologies, was estimated at €200,000. The system was expected to be operational by the start of the 2019 school year[149] but was only completed by early 2020.

Lost copies: Paris and Philadelphia

[edit]The copies of the Plan of Rome kept in the United States and Paris have disappeared: having become dust traps for a culture deemed obsolete, one was shredded, and the other was thrown away.[150]

Sorbonne model

[edit]

The Paris model, originally intended for the Sorbonne, may have been the original version of the model exhibited in Rome in 1911 and Paris in 1913, although Royo believes this model disappeared as it was used as the basis for the 1933 model.[115] This first version no longer exists, except in photographs and a plan.[151]

The model was kept at the Institute of Art and Archaeology, whose building was designed by Bigot between 1925 and 1928[152] and built in 1930;[24] this structure "constitutes his major architectural achievement."[153] Installed on the fourth[1] and top floor of the building in 1933,[91] it served as a teaching tool for topography, architecture, and urban planning[93] of ancient Rome. The model was still being worked on in 1941.[91]

It suffered damage at the end of World War II[154] because it was located under the building’s skylights,[77] which were shattered during the bombings of Paris.[7] The Sorbonne model was destroyed during the events of May 68[60][91][47] as it was thrown out to clear the room.[150] The elements that survived the occupation, known through photographs,[155] were destroyed during the restructuring of the Institute.[156] Other elements present in Bigot’s workshop under the dome of the Grand Palais were destroyed at an unknown time.[47]

Philadelphia model

[edit]Bigot "is sparing with information" about this example of his work,[92] and the available information is scarce.[47]The enthusiasm for Bigot's work presented in Rome in 1911 spread across the Atlantic. Petitions were sent, one in 1912 to Andrew Carnegie and another to John Pierpont Morgan, leading to a 1913 news article aimed at acquiring a copy.[92]

The exact date of creation for this model is not known precisely. According to Royo, it was either created before 1914[99] or at the end of the 1920s when the author sought to fund his bronze plan.[92] The model seems to have been painted by American artists to enhance the realism of the work.[157][92][158]

The destruction, for which the exact time is not known, seems to have been deliberate.[159] Fragments of the model are thought to still exist in Philadelphia in the early 2000s.[92]

Partial elements: The bronze model

[edit]

Project and initial execution

[edit]The Plan of Rome made a sensation in 1911 in Rome and then during the 1913 Paris exhibition at the Grand Palais. Georges Clemenceau initiated a law in the National Assembly[35] that allocated a sum of 80,000 francs to transform the plaster plan into a bronze work, "to make it indestructible."[7] The very fragile plaster risked disappearing,[160] and the aim of the transformation was to make "Rome […] eternal through its bronze image."[105] The transformation of a fragile work into bronze did not take into account the evolution of archaeological data.[161] Bigot later considered the transformation of his work into metal premature.[98]

The relief model underwent its first attempt in bronze by Bertrand, then by Christofle,[24] but this attempt remained unfinished due to World War I[162] and the continuous demands of the work's author.[82] An operation, which generated "major financial and scientific problems,"[34] took place between 1923 and 1927 by Christofle.[99] Bigot exasperated Christofle, who would have been at a loss due to the scale of the task, by incessant requests for modifications,[160] to which he conditioned the payment of the installments. However, Bigot apologized for the changes requested, emphasizing the progress made in the knowledge of the city's topography.[105] Work continued in 1929, but the plan was not delivered, as Bigot refused to accept it due to new changes that still needed to be made.

The elements were finally completed and integrated into the Institute of Art and Archaeology[99] in 42 crates on November 18, 1932.[24] Bigot wanted to continue the project, but faced with the company’s refusal, he postponed it.[163] The funds allocated for the bronze plan were used to modify the plaster model.[164]

Incompletion and rediscovery

[edit]In his 1942 work, Paul Bigot announced a subscription to finish the bronze plan, which remained unresolved due to his death.[105] According to Royo, the architect was aware of the fragility of his work and "intended to protect both time and Rome and his work."[104]

The crates containing the unfinished bronze plan were rediscovered by Hinard in 1986 in the cellar of the building on Rue Michelet,[77][1] where they had been stored without interruption since 1932.[165] The plan was unboxed in 1989.[93] Hinard observed that most of the crates had been opened, several elements had suffered from deformation or oxidation, and it was impossible to assess potential losses.[156]

Some of the crates containing the elements of the bronze plan were kept for a time in the basement of the Law Faculty building at the University of Caen before being returned to its Paris premises. A temporary reassembly of the various parts took place in the mid-1990s, along with photographic documentation, and it was exhibited in the newly opened Maison de la Recherche en Sciences Humaines at the University of Caen while the model belonging to this university was sent for restoration, placed on the purple-colored platform reserved for the work.[124][156] The Bigot model thus regained its "cultural showcase role at the university."[166] The bronze plan was not accessible at the end of the 2010s despite some sporadic exhibitions of several bronze plaques. However, the university's long-term goal remains to restore the model.[156]

Method, characteristics, objectives, and legacy of Paul Bigot's model

[edit]Characteristics and method of Paul Bigot

[edit]Despite the works he has written, Bigot has rarely discussed his method and sources.[167]

General characteristics and sources

[edit]General aspect

[edit]The model, in its final version, occupies an area of about 75 m²[89] and does not correspond to the idea of a small, portable model.[168] This size "does not offer any privileged perspective from which to... dominate it," posing a problem for the viewer who can only apprehend the object as a whole from above and see details only nearby.[169] There is no privileged viewpoint, as the model can be viewed from all sides.[170]

The model consists of about 100 fragments,[108] 102 elements specifically for the Caen version,[107] mostly arranged around an important building,[171] made of plaster with a wood[172] or metal frame.[91] There are differences between versions of his work that have persisted over time.[173] The organization into elements facilitates updates and castings of the work.[107]

Bigot gathered the plates of Lanciani and annotated them to have a mass plan from which to work in his studio.[174] The architect also based his work on comparisons with photographs of marble fragments, which were enlarged and then placed back in the work of the Italian archaeologist.[175]

The relief model is made to be viewed from above, as it is displayed in Brussels or Caen.[172] The relief of the seven hills of Rome is flattened because the viewpoint is 300 meters above sea level.[176] According to Bigot, "When we look at the relief, [...] the roughness fades as we move away."[157] Aerial photographs were first used in archaeology around the turn of the 20th century.[177]

Bigot’s work is very rigorous, and he synthesizes knowledge while also relying on intuition.[33] His intuitions are sometimes confirmed by excavations, such as those of the temple of the nymphs, more than a quarter-century after the positioning of the building on his model.[178] The Plan of Rome is very precise, as a satellite image of the city confirmed the accurate location of the buildings and streets.[5][107] The buildings still extant in 1992 "are rigorously in their place."[179]

Bigot rarely explains his choices,[106] which makes understanding the object difficult. He writes little about his sources and method,[180] though he wrote more than Gismondi.[180] Bigot was driven by the "concern... not to omit anything from the complexity of the urban phenomenon."[181] He wanted to "gather all archaeological knowledge,"[182] and thus conducted scrupulous work over four decades.

Sources

[edit]Bigot, in his submission from Rome, provides neither sources nor bibliography because he did not present a report annexed to his work. The lack of both primary and secondary sources[183] makes apprehending the object difficult.[184] His 1942 work, Rome Antique au IVe siècle apr. J.-C.,[185] provides some elements. Bigot presents a "rapid and mostly allusive inventory,"[183] his work was "something other than the academic result of a historical compilation."[186][186] Bigot knew and used classical literary sources, even though he did not give references.[187] He also knew "artistic and numismatic sources"[188][189] — this use of iconographic, artistic, and archaeological sources, moving beyond solely literary sources, is an originality of his work.[190]

He was also familiar with literature on the topography of Rome written during the Renaissance and the 18th century, in particular. He modeled his work after the studies of Piranesi, and the submissions from Rome were also an important source, including Abel Blouet’s work on the Baths of Caracalla, even though it is unclear why some submissions were excluded from his corpus.[191]

Lanciani's work on the Forma Urbis — the marble map was represented by Bigot in its original location on the wall of the Forum of Peace on his model[192][193] — was fundamental to his approach,[194] which later inspired Gismondi. The marble map of the Severans is a source for work on the Villa Medici from the mid-19th century.[191] Lanciani published 46 plates showing the remains of Rome,[195] and Bigot used half of the plan[194] at a larger scale, modifying it.[81] The work on the Severan map posed interpretative problems.[196]

Bigot rarely cites ancient or contemporary sources, even though he "truly drew from all the archaeological and historical literature" present at the French School in Rome,[197][3] unlike other submissions that provided lists of sources. He was aided by his peers and by Duchesne, the director of the school.[198] He also kept up with current events, which allowed him to make subsequent modifications to his model, though he likely did not leave archives.[199] His colleagues at the French School assisted him, including Albert Grenier, Jérôme Carcopino, Eugène Albertini, and André Piganiol.[200] His bibliography seems to date from the period 1904–1911, as well as the changes linked to the refurbishments of the 1930s.[80] Balty considers that the work "reveals documentation that is already somewhat outdated."[31]

His analysis allowed him to modify certain attributions of fragments of the Severan marble.[201] Even though Bigot closely followed Lanciani's conclusions for his study of the Forma Urbis, he also appealed to the hypotheses of Hülsen and Gatti.[202] Bigot followed ongoing archaeological debates and unsolved questions, adhering to certain hypotheses, such as the location of the Actian Apollo temple. After conducting research and discussions with scholars like Jérôme Carcopino and Italo Gismondi, Bigot revised his proposals on his model. His work was, therefore, the product of an "intellectual ferment"[203] and was not a mere "three-dimensional translation of monuments reconstructed by others."[202]

At the heart of Bigot’s project: the Circus Maximus

[edit]

The Circus Maximus (or Great Circus) fascinated him "for its historical and social significance,"[18] from Romulus to Constantine II,[171] and it was his "beloved child" that dominated the model, acting as a "kind of guiding thread."[113] The circus is seen as "the true center of the relief"[204] and a symbol of the city, "responsible for the birth of the relief."[76][205] The subject was unprecedented at the beginning of the 20th century;[11] Bigot created a longitudinal reconstruction to define its limits and provided a height for the bleachers, along with a cross-section of the cavea and carceres. His work achieved a seating capacity of 159,000 spectators.[206]

Bigot wanted to represent the Circus Maximus in the relief of the Aventine and Palatine hills to highlight the extraordinary dimensions of this structure.[13] According to Ciancio-Rossetto, the relief model came from Bigot’s need to determine the boundaries of the bleachers and the building's relationship with the city's topography, at a time when knowledge was increasing significantly.[63] The relief model, a very new approach,[207] was extended to give perspective to his initial creation and also due to reactions to his work.[208] This first work generated great enthusiasm because it was "more expressive than any drawing," according to Bigot,[25] though he was concerned about the project.[13]

Although the Italians considered the exploration of their capital’s underground "a national issue,"[209] Bigot conducted excavations on this building between November 1904 and July 1906. He published two articles on the subject in 1908[210] to support his argument, particularly regarding the limits of the structure.[211] The academic community received these works with skepticism,[212] but they constituted an important step in the research on this structure, despite errors, such as an extra tier of bleachers and the placement of the carceres.[207] Bigot "contributed... to the construction of knowledge about ancient Rome," and his scientific contributions are significant.[107]

Choice of representation in time and space

[edit]

Bigot chose to represent the city during the time of Constantine I, at "a moment in the history of Roman urbanism and Roman topography,"[213] before the creation of Constantinople and the proclamation of Christianity as the state religion.[214] He selected the same period as Giuseppe Gatteschi (1862-1935) for his restoration drawings of ancient Rome, placed in parallel to contemporary states, a work that took thirty years and was based on sources,[215] some of which dated back to the early 19th century.[216] The early 4th century corresponds to the "monumental peak of ancient Rome" and also to the last truly ancient state in the strict sense,[37] the "completion of a work"[217] at "a level never previously equaled and that will not be surpassed later."[157] This period allows for the representation of all the city's buildings at the time of "its full blossoming,"[218] and the plan is "the synthesis of discoveries concerning the history of Roman monuments still standing in the 4th century and known in the early 20th century."[213] This period was also chosen for other representations, including Gismondi’s model.[219]

Bigot focused on the monumental center of Rome, not the periphery.[220] He represented the center,[87] including part of Trastevere, but excluded the barracks of the Praetorian Guard and the Baths of Diocletian due to their distance from the center—elements that are included in Gismondi’s model. He stopped due to the surface area of his work and lack of space,[173] but also because of the ongoing work required for updates.[194] He also excluded the port of Rome and the horrea,[214] as these were not of interest to him. The cessation of his work's extension was due to fatigue and, in his words, the approach of a zone of gardens in the spaces to be represented, while his model had already become vast.[221]

The "burdensome monumentality symbolically transposes the grandeur" of the city.[169] It is surprising that Bigot excluded areas that could have been of interest for sites of Christian worship, given that his work evokes Rome in the 4th century, such as St. Peter’s Basilica and the Lateran.[194][222]

Method

[edit]The representations of the most important buildings in the city are the result of a subjective approach that was not explicitly explained and whose genesis is difficult to trace.[223] He had to make decisions for the reconstructions, focusing on filling in the gaps, and in doing so, made "more or less conscious" mistakes.[224]

Ongoing work to be revised

[edit]Despite similarities to the submissions from resident architects who chose watercolors, Bigot showed a concern for objectivity and the updating of his work.[225] With his readings, the architect was led to make choices for his reconstruction.[190] Starting from the Forma Urbis, he interpreted and extrapolated the elements provided by Lanciani,[194] using them to justify his own choices.[192] He also sought elements on the ground to confirm or disprove his hypotheses, drawing conclusions from them.[19]

The relief plan was initially perceived as final, but it was with new discoveries that Bigot realized the need to update it.[164] His desire to produce the "counterpart of reality" would be the reason for the numerous changes the architect undertook.[226] Throughout his life, he reworked his model as archaeological discoveries allowed him to clarify previously unknown areas or change the identifications he had proposed.[227] The desire for updating is responsible for the failure to transform the plan into bronze, as the Christofle company was "exasperated by Paul Bigot's meticulous perfectionism and the extra costs it entailed."[218] He continued to incorporate discoveries until the end of the 1930s,[37] even though some of these works were not used to update his relief.[228]

In 1942, Bigot apologized for the revisions to his plan, stating, "the image of the city can only be given by approximations," and "this is already a lot."[229] He noted the significant progress in the knowledge of Rome’s topography since the 1880s.[230] Bigot never considered his work finished, and the differences between his final version and the initial works are significant, consequences of major work in the Italian capital.[113] Bigot’s revisions could be observed during the restoration of the Caen model in 1995.[128]

Bigot did not create just one model but several.[26] Over the course of his work, it expanded and became "a moving surface." Continuously, he made "modifications, additions, or revisions"[231] to keep up with the latest discoveries in the archaeological topography of ancient Rome. These changes affected 29 modules out of the 102 in the Caen version, about 25%.[232] Modules were added at the northern entrance of the city, as well as to the north and east of the Esquiline, stopping at the Baths of Diocletian, a well-known and studied building due to its state of preservation. He also modified the southeast of the Aventine with the Baths of Decius and expanded the east side of the Caelius and Esquiline to achieve a more complete vision of the city. He worked on the area of the Imperial Forums,[233] then on the Campus Martius, and extended his work on the side of the Trastevere.[234][235]

The reconsiderations of the choices made initially as knowledge and archaeological excavations advanced in the 1930s[236] led to changes in the model,[98] especially in 1937.[98] The changes made are rarely dated during the interwar years,[237] except when the author mentions them specifically.[238] These revisions are a sign of "a scrupulous update of his sources."[239]

Bigot removed elements as research progressed, particularly for the 1937 World's Fair, and some modules were "declassified." However, not all his reliefs were modified: the Caen and Sorbonne plans were updated for the location of the Porticus Aemilia, but the plans of Brussels and Philadelphia were not.[240] Royo notes that the southern district of the Aventine was not modified, even though Bigot had located the Porticus Aemilia and the Horrea Galbana.[235] The architect changed the location of the Curia of Pompey, integrating it into the Pompeian portico on the plaster model, but the Curia remained integrated into the Largo Argentina in the partial bronze model.[241] He modified the Imperial Forums using Gismondi's work, raising the question of the relationship between the two architects.

Complete work: the necessary local color

[edit]The French architect emphasized the importance of "local color" in his 1942 work, and the diversity of materials present in the city.[242] The first plan of Bigot, as mentioned in the publication of the Rome dispatches, depicted the unknown spaces with "hatching patterns," areas that would be filled in the final version.[183] Many spaces in the city—monuments, homes, emporia, and roads—were unknown, and Bigot's plan risked having "many voids,"[28] making his work resemble only a skeleton.[73] The unknown spaces were completed with "local color" as part of a "project of architecture," and he adapted previous works to avoid presenting a plan with gaps.[243]

Faced with the void, the architect chose to relegate "the accuracy of details in favor of an overall impression."[6] According to Bigot, "One cannot imagine an assembly of partial resurrections separated by voids that evoke interplanetary spaces."[244] Some sectors are treated "in the manner of an architectural project" with an obvious concern for plausibility.[245]

Bigot uses the Regionnaires and the Severan marble plan to define the average size of the insulae and domus. He proposes a figure for the city's population[246] and its distribution. Through calculations of the surface area distribution in Rome and by analogy with the population density of Paris, he manages to calculate the size of the population of the capital of the Roman Empire.[247] He also attempts to give a capacity for the entertainment buildings.[87]

He reproduces the ancient urban fabric[87] based on the Forma Urbis and the excavations at Ostia.[144] He places insulae in areas not definitively known to have been occupied by such constructions.[248] Furthermore, he situates domus with peristyles in the center of Rome.[249] The architect places buildings and decorative elements with "at best plausible integration, at worst fanciful." He draws upon archaeological data, the contributions of Lanciani, and personal interpretations.[250]

There is a contradiction in Bigot's project between the comprehensiveness sought and the presence in the model of areas treated as projects, plausible images of reality.[144] However, he mobilizes as many sources as possible to "get as close as possible to archaeological reality," even though his work is, by nature, "always incomplete and yet finished."[167] Bigot makes aesthetic choices for his model that are sometimes confirmed archaeologically much later: for example, a street near the Vigna Barberini was confirmed in the 1980s.[251] He places the Temple of Apollo, located near the Theatre of Marcellus, in the correct spot, discovered only in 1939-1940.[252] However, his work is a "recreation... without direct relation to reality."[253]

Voluntary and involuntary errors

[edit]

Royo identified "exceptional errors" in the displacement of buildings or their identification.[231] Some errors appear to be involuntary, particularly those related to issues with the connections of enlarged plans from Lanciani, while others seem intentional, as the plan was not updated even though more historically accurate information had become available. For example, errors in the orientation of buildings were not corrected, even though archaeology had advanced, particularly regarding the Temple of Peace and the Temple of Apollo at the Circus Flaminius.[233] Bigot extrapolated from Lanciani's work, and thus the Brussels model partially represents the Naumachia of Augustus. He sometimes places plausible or fanciful buildings.[249] His decisions regarding the model are sometimes premature, given the knowledge of the buildings discovered at the time.[81]

The knowledge of the Campus Martius, an area that had been the subject of prestigious construction plans, was incomplete at the time of Bigot, even though the district had retained its ancient plot structure. "Bigot's Campus Martius bears... the mark of the knowledge of his time."[254] Work on the Severan marble plan accelerated in the second half of the 20th century,[255] particularly in this area. Bigot inverted the locations of the Theatre of Balbus and the Circus Flaminius, an error due to the unknown locations of these two buildings at the time,[5] an error repeated by his contemporaries,[175] which was corrected by Gatti only in 1960.[256] The Temple of the Forum of Trajan is also misplaced.[257] The knowledge of this forum evolved with excavations in the early 2000s, and it appears that the temple was located next to the Forum of Augustus, not as Bigot had supposed.[114]

The Horologium Augusti is placed correctly in the model for its Augustan configuration, while in the Constantinian period, the space was built over. This representation, a "gross error,"[217] in what is meant to be a model of Rome in the 4th century, is also anachronistic due to disturbances caused by recurrent flooding in the area. Similarly, the author does not represent urban wastelands, even though they are attested to in the 4th century due to a contraction of the city,[217] which accelerated in the following century. This type of error cannot be involuntary and is a result of the path chosen by the creator of the relief.

Bigot was aware of works that could lead to changes in his model but did not always implement them, such as for the Curia Julia[31] or the Saepta Julia.[95] The location of the Saepta is modified on the Caen model.[235] For the Gardens of Adonis, he indicates they were not located on the Palatine Hill but does not apply this information to his model. Excavations in 1931 confirmed Bigot's theory. The Brussels model was modified. The architect does not seem to have shown interest in the Palatine Hill and Alfonso Bartoli's work on the Flavian Palace in the late 1920s, even though he was interested in the Vigna Barberini.[178] The Palatine Hill underwent considerable archaeological work, and Bigot's vision was based on the 19th-century understanding of the area. Nevertheless, he did modify the sector in the last version of his model, with treatment given to the House of Augustus and the Temple of the Vigna Barberini, leading to relocations of monuments and raising still-relevant questions.[258]

Bigot also sometimes used the Forma Urbis in a selective way, so as not to deviate from his image of the city. He excluded certain fragments of the marble plan, such as perpendicular straight lines, which "clashed with Rome."[259] Some fragments were artificially integrated, and Bigot invented a Via Septimiana.[260]

Originality and posterity

[edit]Bigot's Plan of Rome is an original work in more than one way; it is also a tribute to the City. Nearly contemporary with another great architect who produced a much more famous model, Italo Gismondi, the question of their relationships and influences arises.

Original work

[edit]Bigot's Envoi de Rome, "an archaeological summa and [...] a picture of urban genesis"[167] and "an extraordinary scientific achievement,"[261] possesses a triple originality: it represents a city, not an isolated building; it is a model, not a drawing; it is a work that he continually pursues, not a mere Envoi de Rome. In other works, the architect integrates his character, which "closely associates the monument and the city, that is, architecture and urbanism."[262] According to Royo, the work "is emblematic of a certain historical approach and a particular perception of the city at the end of the last century, caught between urban dream and reality."

Rome presents "the anarchy of centuries of sedimentation," but Bigot offers a reading of the city's complexity.[263] Unlike Lacoste, who applies the urban project—colonial-type voluntary urbanism—to the Brussels model, Bigot gives a rational vision of the city's development.[141] The French architect represents the complex urban phenomenon of the accumulation of buildings in the City related to streets and residential areas, not just isolated buildings or architectural ensembles like Marcelliani.[264] Unlike Henry Lacoste, Bigot does not believe that Roman urbanism followed a plan before the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. He assigns a central role to Nero in the city's urban planning after the disaster, even if he considers the work incomplete.[265]

Bigot’s desire to represent the City as a whole is original in relation to his contemporaries, Italo Gismondi and Giuseppe Marcelliani.[266] The plan is "the sum of the scientific knowledge of an era" concerning the topography of ancient Rome.[267] It is not only a model but also "a global representation."[268] In this regard, Bigot is closer to Garnier's conceptions, as both believe that "urban organization is the response to the fatigue caused by the repetition of a school exercise."[6] Garnier learns lessons from Antiquity through the organization of his project, even though he rejects "an academic and dusty image of Antiquity." Bigot, on the other hand, is trapped in "an encyclopedic and artistic concern [...] and [...] an exhaustive reconstruction."[269]

However, due to the "analytical qualities and [the] intuitions of its author," the model remains worthy of interest because of the archaeological confirmations of Bigot’s proposals, in addition to "the very concrete nature of his work."[270] His work is "meritorious and visionary" at a time when the ancient city was still hidden in many ways.[200] According to Élisabeth Deniaux, the plan is "the visual translation of the culture of an era about the city that transmitted its civilization to the Western world."[106]

Bigot’s Plan of Rome is not just a record of knowledge about the topography of imperial Rome; it is, according to Manuel Royo, "a paradoxical object of art that gives grandeur the aspect of a miniature and eternity the face of history."[271] It is "also and above all a testament to the architect's veneration for an image of Rome straight out of classical studies,"[219] "an urban utopia [and] a projection of the intimate universe of its creator."[272] Royo believes the work is a global vision "where the sense of grandeur, diversity, even eternity, comes together."[273] The plan "summarizes a certain idea of the city,"[274] it is a place of memory,[275] destined to be exhibited in a museum.[276] Bigot’s Plan of Rome belongs to the dreamlike world, and this is perhaps the reason for the absence of human figures in Bigot’s vision.[277]

According to Royo, the plan is a singular object with a "contradiction between the encyclopedic desire of its author and his approach, which is as sensitive as it is aesthetic, to Antiquity."[109] The bronze model conveys his "temptation of eternity,"[105] but "a fragile eternity,"[278] and is "the result of an effort to clarify [the] intertwined layers in favor of just one of them, fragmentary and constantly reworked."[278] Bigot's work is a cultural effort, but he is also concerned with ensuring the continuation of his interpretative work.[278]

Models of ancient Rome were still created at the very end of the 20th century: thus, in 1980, Augustan Rome was represented on 4 m² at the Antikenmuseum in Berlin, and in 1990, a 20 m² model depicting Rome during the reigns of the Tarquins was created for the Museum of Rome.[279] A model of archaic Rome was also made around the same time.

Complex tribute to the ancient city

[edit]

Bigot’s model does not serve an ideological, political, or military function, unlike other relief plans;[280][281] the plan is also, for its author, an aesthetic object,[282] driven by both "artistic and scientific approaches."[95]

Through his work, Paul Bigot is concerned with representing the grandeur of the City during Antiquity, giving "a sort of vision of the grandeur of Rome,"[283] but also the urbanism of Rome, which had become the capital of a modern state about a quarter of a century earlier.[71] The plan expresses "the monumentality of what it represents."[284]

His work evokes both the "grandeur of ancient Rome" and "a vision of an urban planner." Thus, it is an ambiguous object[285] that aims to gather "the totality of topographical and historical knowledge about ancient Rome."[286] Bigot's Plan of Rome allows one to "substitute an intact and therefore glorified image for the destroyed Rome."[287]

According to Manuel Royo, Bigot’s Plan of Rome possesses "didactic, artistic, technical, and historical" characteristics.[266] The object is the result of "a sensitive experience of the City and [...] a theoretical conception of ancient urban space."[10] The author's concerns are both pedagogical and aesthetic.[288] Bigot’s work reflects his "historical, archaeological, and urban vision,"[289] and it is an invitation for a "journey through time and space."[290]

The work is also "a cultural icon offered for the veneration of the eye, leading to a sort of virtual resurrection of ancient Rome."[291] With the planned audiovisual installation, the architect desires a "global perception of the historical and geographical territory of Rome" for the viewers.[292] His city is "an entirely theoretical and cultural universe."[293]

Bigot offers a fictive journey[10] to the viewer, with the visit marked by the main buildings,[294] which are juxtaposed in an ideal state of conservation.[295] The model, however, allows for "an infinity of possible journeys [and] a layering of unique stories,"[296] excluding the evolution of the different monuments.[217] This journey enables the management of various historical layers within a single object.[297]

Paul Bigot is the only one to have written about his relief plan. His brochure was published in 1911 and then reissued in 1933 and 1937.[289] These works consider the reader as a spectator and, therefore, have characteristics typical of travel narratives.[266] The works also contain anecdotes.[298] The French architect published another book in 1942, which was reissued in a shortened version, accompanied by the brochure's text in Belgium by Lacoste in 1955,[267] and enriched with illustrations and texts meant for a literary stroll.[299] The frontispiece of his works features an eagle with outstretched wings at the center of a laurel wreath, based on a relief from the Church of the Holy Apostles. This representation is present on the façade of the Institute of Art and also in the form of a mold in the building.[300] This "ambiguous aesthetic," because it was extensively used by Italian fascism, was abandoned in the reissue by Lacoste in 1955.[301]

Lacoste integrates figures into the photographs of the plan.[272] This visit is a journey, a "topographical inventory (...) [punctuated] by historical and anecdotal reminders,"[246] an element of a "minimal encyclopedic knowledge."[302] These journeys are particularly visible in the early works published by Bigot about his model. According to him, the visitor should refer to the "explanatory legend"[289] and thereby perceive the organization of urban space.[303]

Model for Gismondi's model?

[edit]

Paul Bigot's scientific and educational work inspired[304] or was imitated by the architect and archaeologist Italo Gismondi, but commissioned by Mussolini for propaganda purposes,[84] combining "antiquity and the present day, models and real constructions."[305] The architect also used Gismondi's archaeological works,[252] especially after his trip to Italy in 1934, but did not use the Italian architect's model.[178] The emulation created by Bigot’s work and the pride it instilled explain Gismondi’s work from 1930 onward, which is both "more complete... and more famous."[82] Gismondi is also, in a way, the successor of Bigot,[305] his work considered as surpassing Bigot’s.[306] Gismondi's model aligns with the fascist vision of the grandeur of Rome, serving "as an ideal reference and substitute for reality,"[306] and allowing for the extrapolation of incomplete archaeological research (such as the imperial forums, interrupted by the construction of the major axis that bears its name) or preserving the memory of destroyed elements, like those on the Velia.[96]

The model, begun in 1933,[307] was exhibited in 1937 at the Mostra Augustea della Romanità (Augustan Exhibit of Romanity). The stated goal was to celebrate the bimillenary of Augustus' birth through grand ceremonies. It played a central role in these ceremonies, alongside models of Augustus' temple and the city of Ancyra, the site of the discovery of the primary source of the Res Gestae.[84] After the fall of the fascist regime, Gismondi’s work lost its political dimension and regained its status as a "true object of study."[305]

It was reworked by Gismondi for about 40 years,[79] incorporating new knowledge.[307] He based it on the works of Lanciani and Guglielmo Gatti. There is no direct evidence of contact between Bigot and Gismondi, but the 1911 exhibition provided Gismondi with "very rich and fundamental documentation."[308] The Italian archaeologist benefitted from discoveries related to the deep restructuring of Rome in the 1930s.[309]

For spaces or monuments where uncertainties lingered, Gismondi operated by analogy or presented "volumes in the form of large masses" on his plan. He depicted the Servian Wall as a ruin.[310] Gismondi also utilized Bigot’s work on residential buildings and developed a typology to place them on his model.[307]

Exhibited at the Esposizione Universale di Roma (EUR) in the Museum of Roman Civilization, intended for the World’s Fair planned for 1942,[311] the Italian model, called Il Plastico, is larger (1/250 scale)[79] and depicts the entirety of ancient Rome. It was updated until 1970, whereas Bigot’s model reflects the state of knowledge in 1942, the year of his death. Gismondi’s model ultimately represents the entire area within the Aurelian Wall, excluding Trastevere and the Vatican.[312] A project to restore Region XIV was under consideration in the early 1990s, as well as the creation of "a true and authentic digital map of ancient Rome" to establish a database and create "an illustrated manual for everyone."[313]

Gismondi's model covers 240 m².[314] It is made from plaster derived from alabaster powder, reinforced with metal and plant fibers. Initially conceived in plaster, the reliefs were particularly worked on and accentuated by 15 to 20%.[315] The larger scale allows for more details to be displayed. The relief is better represented, and the materials have a more realistic appearance, with green stains for gardens.[316] Paola Ciancio Rossetto considers the work "more faithful to reality and the discoveries" and believes its author interprets less.[79]

Gismondi used his knowledge of the site of Ostia, which he excavated,[317] for his model of Rome, and he made two 1/500 scale models of it.[310]

While Bigot recounted his difficulties with the issues his work posed, Gismondi left no documentation other than drawings or sketches of reconstructions.[307][109] His model is "a possible and silent projection of archaeological reality."[305] However, according to Paola Ciancio Rossetto, Gismondi is "the successor of Bigot’s work," but in a "more concrete, more realistic, and less passionate" manner.[318] Paul Bigot’s Plan of Rome, however, remains "an irreplaceable model... both for its technical aspects and its topographical documentation."[310]

Development of the "virtual double" by the University of Caen

[edit]Bigot's model is a heritage object that cannot be modified. The use of a "virtual double" allows for the representation of the most recent data and provides a tool for teaching and research.[319] The virtual model serves both a scientific purpose, with direct access to sources,[320] and an educational and media role,[321] creating "a form of digital encyclopedia on Rome."[322] The proposed models are interactive and aim at research, pedagogy, and public outreach; they are a "tool for visualizing a reality that is difficult to perceive today."[37]

Teamwork and resources

[edit]Projects of this nature are costly, requiring "considerable human, material, and financial resources."[323]

Multidisciplinary teamwork and partnerships

[edit]

In 1970, Louis Callebat founded the Center for Ancient Studies and Research at the University of Caen, which worked briefly on computer applications for ancient languages.[324]

Since the early 1990s, a multidisciplinary team formed around Philippe Fleury, a Latin professor with a passion for computing,[325] who began his work in the laboratory for the computerized analysis of texts. Fleury is a specialist in Vitruvius and ancient mechanical systems.[326] The formation of the "City-architecture, urbanism, and virtual image"[124] multidisciplinary pole, the partnership, and methodological work took place from September 1993 to December 1995. In 1994, the Plan of Rome team was formed, including members of the Center for Ancient Studies and Myths (CERLAM), with added expertise in architecture, computing,[126] history, and art history,[327] at the same time as the construction of the Humanities Research House (MRSH).[328] In the early 2000s, the team had about ten members.[5] Every two years, the work is evaluated by a scientific committee.[120]

The team is working on a virtual reconstruction of ancient Rome, contemporaneous with Bigot's model, but "scientifically up to date" and "modifiable at all times." Gérard Jean-François, director of the University of Caen's Center for Computing Resources, and Françoise Lecocq were part of this team.[329] The reconstruction began in January 1996.[319]

By December 10, 1998, about twenty buildings were modeled, including around ten related to the Forum Boarium and the Temple of Portunus.[330] The Curia and the Temple of Portunus were the first buildings to be reconstructed.[331] By the early 2000s, around thirty elements were reconstructed, including buildings and mechanical elements.[61] Ancient machines, such as war machines and the hydraulic organ, were also reconstructed, as well as other elements like the floods of the Tiber, Augustus' Horologium, and the raising of the obelisk of Constantine.[332][333] In 2002-2003, two projects were initiated: Virtualia, aimed at promoting productions and responding to commissions, and the construction of a virtual reality center.[334]

The initial goal was to complete the model of Rome during the time of Constantine by 2010, but this was revised to 2015.[335] Major changes in the organization of the team around 2006 complicated the achievement of this ambitious goal. The rapid evolution of computer hardware and software also made the early models obsolete, requiring them to be redone.[121]

Partnerships were established to find a new dynamic. By 2011, 25% of the virtual model was completed during the partnership with the University of Virginia’s Rome Reborn project, which produced a "more basic but complete" model.[37] The project was led by a team under Bernard Frischer and Diane Favro in the Cultural Virtual Reality Lab.[159] Local partnerships allowed for work in the early 2000s on the reconstruction of the city of Saint-Lô before the bombing during the Normandy Invasion.[61] The experience gained was applied to the reconstruction of other buildings destroyed in 1944, such as the former town hall of Caen or the former university of Caen, in partnership with the city of Caen and the Cadomus association, or the reconstruction of famous Norman buildings at various points in their history, such as the Saint-Pierre Church in Thaon.

Material and financial resources

[edit]The financial resources in 2003 came from CERLAM, MRSH, the University of Caen, the state, the CNRS, the DRAC, the city of Caen, and the Lower Normandy region.[335]

Sales of products, images, and multimedia materials also generate revenue[321] and enhance the research work.[322] Requests for 3D images from the print and audiovisual media have been fulfilled: not only were images related to the Roman world created, but also ones about Native American civilizations or reconstructions of elements from the Atlantic Wall.[336] These various reconstructions are part of the American project Rome Reborn, and while the method brings "notoriety and... income," it disperses the energies compared to the original project.[261]

Since 2006, the team has been integrated into the Interdisciplinary Center for Virtual Reality,[131] a member of the French Virtual Reality Association, with the goal of both sharing technical and human resources and promoting the use of virtual reality, "both a science and a technique."[337] In 2003, around ten research fields at the University of Caen had expressed interest in virtual reality,[338] and studies began.[328][339] The technical platform set up in 2006 has the necessary equipment for virtual reality as well as the essential staff, also responsible for promoting the use of the technique and providing the necessary support. It initially had an auditorium that could seat 200 people.[328] In addition to a graphics calculator and a video switching system, the location includes an immersive room designed to display virtual models in high resolution, "a place for enhancing research and... a place for scientific experimentation," according to Philippe Fleury.[339] Since 2008, the scientific framework for the project has been ERSAM, "Technological Research Team Education, Ancient Sources, Multimedia, and Plural Audiences."[340][131]

Additional work is planned from 2011.[328] A 45-square-meter virtual reality room, whose construction was initially planned for 2007,[341] has been operational since December 2016[342] and was inaugurated on March 2, 2017.[343] This equipment, costing 1.2 million euros,[344] was financed 60% by the Normandy region.[345] The available space in 2016 was 618 square meters.[328]

CIREVE aims to represent "disappeared, degraded, inaccessible, or future environments," experiment in the most diverse fields, and serve as a training tool.[328] The experience gained from the reconstruction of Rome has provided "methodological gains."[346]

Method

[edit]The virtual model has been used in architecture for a long time, and its use has spread in scientific circles as it allows for "immersion and total illusion."[347] In the Caen project, "advances in technology [are] at the service of ancient Rome." Furthermore, the work has not only a scientific scope but also "an effort to highlight and preserve cultural heritage."[323]

The team began with "the restitution of the visible," of buildings still in existence, such as the Temple of Portunus and the Curia Julia, before focusing on "restoring the invisible."[348] The work is based on the organization of Bigot's model modules.[349] The team's goal is to build a realistic reconstruction within an interactive virtual model.

Realistic reconstruction based on scientific analysis of sources

[edit]

The goal of the reconstructions is not to create illustrations like those found in non-scientific publications or even video games but to "visually disseminate scientific syntheses and demonstrate the validation of certain hypotheses."[350] Only buildings for which documentation exists can be fully reconstructed, both inside and outside.[322]

The digital method allows for updating Bigot's model of Rome, which cannot be modified due to its classification. Bigot wrote that a "subject of this kind is subject to perpetual modifications."[351] The virtual model, by nature, is "reversible and modifiable at any time."[352]

The restitution is created at a 1:1 scale at a specific moment in time, June 21 at 3:00 p.m., and focuses on the city during the time of Constantine, in 320.[353] This emperor's reign was also the choice made by Paul Bigot for his model. Therefore, a comparison between the two works is possible.[322] This period is also the richest in archaeological sources[37] and represents Rome's "monumental peak."[327][354] The team's long-term goal is to propose reconstructions for other periods in Roman history, such as the monarchy, the time of the Scipios, and the end of Augustus' reign.[327]

The team's work aims to propose architectural and topographical hypotheses, including mechanical systems related to buildings in use during the Roman era (velum, stage curtain, etc.). They create a "field of visualization and experimentation" to check for inconsistencies and discuss the different possibilities for reconstruction.[37] The team strives to restore a plausible image, considering both the known elements and those not attested but reconstructed to give an image of the building as it could have appeared. Access to the sources allows the public to access the scientific dossier.[355] The virtual restitution has helped rule out hypotheses, particularly for the velum of the Theatre of Pompey, with the traditional hypothesis making the lighting of the upper-class seats seem poor.[356] For the restitution of the machines, the team draws on the works of Vitruvius: in addition to the velum, the team has worked on how to erect an obelisk in the Circus Maximus, lifting machines, weapons (scorpion), and the hydraulic organ.[357]