Doo-wop

| Doo-wop | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | 1940s–1950s, African American communities across some major cities on the East Coast |

| Derivative forms | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Other topics | |

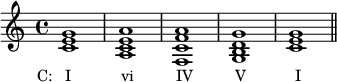

| '50s chord progression | |

Doo-wop (also spelled doowop and doo wop) is a subgenre of rhythm and blues music that originated in African-American communities during the 1940s,[2] mainly in the large cities of the United States, including New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Baltimore, Newark, Detroit, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.[3][4] It features vocal group harmony that carries an engaging melodic line to a simple beat with little or no instrumentation. Lyrics are simple, usually about love, sung by a lead vocal over background vocals, and often featuring, in the bridge, a melodramatically heartfelt recitative addressed to the beloved. Harmonic singing of nonsense syllables (such as "doo-wop") is a common characteristic of these songs.[5] Gaining popularity in the 1950s, doo-wop was "artistically and commercially viable" until the early 1960s and continued to influence performers in other genres.

Origins

[edit]Doo-wop has complex musical, social, and commercial origins.

Musical precedents

[edit]Doo-wop's style is a mixture of precedents in composition, orchestration, and vocals that figured in American popular music created by songwriters and vocal groups, both black and white, from the 1930s to the 1940s.

Such composers as Rodgers and Hart (in their 1934 song "Blue Moon"), and Hoagy Carmichael and Frank Loesser (in their 1938 "Heart and Soul") used a I–vi–ii–V-loop chord progression in those hit songs; composers of doo-wop songs varied this slightly but significantly to the chord progression I–vi–IV–V, so influential that it is sometimes referred to as the '50s progression. This characteristic harmonic layout was combined with the AABA chorus form typical for Tin Pan Alley songs.[7][8]

Hit songs by black groups such as the Ink Spots[9] ("If I Didn't Care", one of the best selling singles worldwide of all time,[10] and "Address Unknown") and the Mills Brothers ("Paper Doll", "You Always Hurt the One You Love" and "Glow Worm")[11] were generally slow songs in swing time with simple instrumentation. Doo-wop street singers generally performed without instrumentation, but made their musical style distinctive, whether using fast or slow tempos, by keeping time with a swing-like off-beat,[12] while using the "doo-wop" syllables as a substitute for drums and a bass vocalist as a substitute for a bass instrument.[6]

Doo-wop's characteristic vocal style was influenced by groups such as the Mills Brothers,[13] whose close four-part harmony derived from the vocal harmonies of the earlier barbershop quartet.[14]

The Four Knights' "Take Me Right Back to the Track" (1945), the Cats and the Fiddle's song "I Miss You So" (1939),[15] and the Triangle Quartette's even earlier record "Doodlin' Back" (1929) prefigured doo-wop's rhythm and blues sound long before doo-wop became popular.

Elements of doo-wop vocal style

[edit]In The Complete Book of Doo-Wop, co-authors Gribin and Schiff (who also wrote Doo-Wop, the Forgotten Third of Rock 'n' Roll), identify five features of doo-wop music:

- it is vocal music made by groups;

- it features a wide range of vocal parts, "usually from bass to falsetto";

- it includes nonsense syllables;

- there is a simple beat and low key instrumentals; and

- it has simple words and music.[16]

While these features provide a helpful guide, they need not all be present in a given song for aficionados to consider it doo-wop, and the list does not include the aforementioned typical doo-wop chord progressions. Bill Kenny, lead singer of the Ink Spots, is often credited with introducing the "top and bottom" vocal arrangement featuring a high tenor singing the intro and a bass spoken chorus.[17] The Mills Brothers, who were famous in part because in their vocals they sometimes mimicked instruments,[18] were an additional influence on street vocal harmony groups, who, singing a cappella arrangements, used wordless onomatopoeia to mimic musical instruments.[19][20] For instance, "Count Every Star" by the Ravens (1950) includes vocalizations imitating the "doomph, doomph" plucking of a double bass. The Orioles helped develop the doo-wop sound with their hits "It's Too Soon to Know" (1948) and "Crying in the Chapel" (1953).

Origin of the name

[edit]Although the musical style originated in the late 1940s and was very popular in the 1950s, the term "doo-wop" itself did not appear in print until 1961, when it was used in reference to the Marcels' song, "Blue Moon", in The Chicago Defender,[21][22] just as the style's vogue was nearing its end. Though the name was attributed to radio disc jockey Gus Gossert, he did not accept credit, stating that "doo-wop" was already in use in California to categorize the music.[23][24]

"Doo-wop" is itself a nonsense expression. In the Delta Rhythm Boys' 1945 recording, "Just A-Sittin' And A-Rockin", it is heard in the backing vocal. It is heard later in the Clovers' 1953 release "Good Lovin'" (Atlantic Records 1000), and in the chorus of Carlyle Dundee & the Dundees' 1954 song "Never" (Space Records 201). The first hit record with "doo-wop" being harmonized in the refrain was the Turbans' 1955 hit, "When You Dance" (Herald Records H-458).[23][25] The Rainbows embellished the phrase as "do wop de wadda" in their 1955 "Mary Lee" (on Red Robin Records; also a Washington, D.C. regional hit on Pilgrim 703); and in their 1956 national hit, "In the Still of the Night", the Five Satins[26] sang across the bridge with a plaintive "doo-wop, doo-wah".[27]

Development

[edit]

The vocal harmony group tradition that developed in the United States after World War II was the most popular form of rhythm and blues music among black teenagers, especially those living in the large urban centers of the East Coast, in Chicago, and in Detroit. Among the first groups to perform songs in the vocal harmony group tradition were the Orioles, the Five Keys, and the Spaniels; they specialized in romantic ballads that appealed to the sexual fantasies of teenagers in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The nonsense string of syllables, "doo doo doo doo-wop", from which the name of the genre was later derived, is used repeatedly in the song "Just A Sittin' And A Rockin", recorded by the Delta Rhythm Boys in December 1945.[28] By the mid-1950s, vocal harmony groups had transformed the smooth delivery of ballads into a performance style incorporating the nonsense phrase[29][22] as vocalized by the bass singers, who provided rhythmic movement for a cappella songs.[30] Soon, other doo-wop groups entered the pop charts, particularly in 1955, which saw such cross-over doo-wop hits as "Sincerely" by the Moonglows,[31] "Earth Angel" by the Penguins, the Cadillacs' "Gloria", the Heartbeats' "A Thousand Miles Away", Shep & the Limelites' "Daddy's Home",[32] the Flamingos' "I Only Have Eyes for You", and the Jive Five "My True Story".[33]

Teenagers who could not afford musical instruments formed groups that sang songs a cappella, performing at high school dances and other social occasions. They rehearsed on street corners and apartment stoops,[30] as well as under bridges, in high school washrooms, and in hallways and other places with echoes:[12] these were the only spaces with suitable acoustics available to them. Thus they developed a form of group harmony based in the harmonies and emotive phrasing of black spirituals and gospel music. Doo-wop music allowed these youths not only a means of entertaining themselves and others, but also a way of expressing their values and worldviews in a repressive white-dominated society, often through the use of innuendo and hidden messages in the lyrics.[34]

Particularly productive doo-wop groups were formed by young Italian-American men who, like their black counterparts, lived in rough neighborhoods (e.g., the Bronx and Brooklyn), learned their basic musical craft singing in church, and would gain experience in the new style by singing on street corners. New York was the capital of Italian doo-wop, and all its boroughs were home to groups that made successful records.[35]

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, many Italian-American groups had national hits: Dion and the Belmonts scored with "I Wonder Why", "Teenager in Love", and "Where or When";[36] the Capris made their name in 1960 with "There's a Moon Out Tonight"; Randy & the Rainbows, who charted with their Top 10 1963 single "Denise". Other Italian-American doo-wop groups were the Earls, the Chimes, the Elegants, the Mystics, the Duprees, Johnny Maestro & the Crests, and the Regents.

Some doo-wop groups were racially mixed.[37] Puerto Rican Herman Santiago, originally slated to be the lead singer of the Teenagers, wrote the lyrics and the music for a song to be called "Why Do Birds Sing So Gay?", but whether because he was ill or because producer George Goldner thought that newcomer Frankie Lymon's voice would be better in the lead,[38] Santiago's original version was not recorded. To suit his tenor voice Lymon made a few alterations to the melody, and consequently the Teenagers recorded the song known as "Why Do Fools Fall in Love?". Racially integrated groups with both black and white performers included the Del-Vikings, who had major hits in 1957 with "Come Go With Me" and "Whispering Bells", the Crests, whose "16 Candles" appeared in 1958, and the Impalas, whose "Sorry (I Ran All the Way Home)" was a hit in 1959.[39] Chico Torres was a member of the Crests, whose lead singer, Johhny Mastrangelo, would later gain fame under the name Johnny Maestro.[40]

Female doo-wop singers were much less common than males in the early days of doo-wop. Lillian Leach, lead singer of the Mellows from 1953 to 1958, helped pave the way for other women in doo-wop, soul and R&B.[41] Margo Sylvia was the lead singer for the Tune Weavers.[42]

Baltimore

[edit]Like other urban centers in the US during the late 1940s and early 1950s, Baltimore developed its own vocal group tradition. The city produced rhythm and blues innovators such as the Cardinals, the Orioles, and the Swallows.[43] The Royal Theatre in Baltimore and the Howard in Washington, D.C. were among the most prestigious venues for black performers on the so-called "Chitlin Circuit",[44] which served as a school of the performing arts for blacks who had migrated from the deep South, and even more so for their offspring. In the late 1940s, the Orioles rose from the streets and made a profound impression on young chitlin' circuit audiences in Baltimore. The group, formed in 1947, sang simple ballads in rhythm and blues harmony, with the standard arrangement of a high tenor singing over the chords of the blended mid-range voices and a strong bass voice. Their lead singer, Sonny Til, had a soft, high-pitched tenor, and like the rest of the group, was still a teenager at the time. His style reflected the optimism of young black Americans in the postmigration era. The sound they helped develop, later called '"doo-wop", eventually became a "sonic bridge" to reach a white teen audience.[45]

In 1948, Jubilee Records signed the Orioles to a contract, following which they appeared on Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scout radio show. The song they performed, "It's Too Soon to Know", often cited as the first doo-wop song,[46] went to number 1 on Billboard's "Race Records" chart, and number 13 on the pop charts, a crossover first for a black group.[47][48] This was followed in 1953 by "Crying in the Chapel", their biggest hit, which went to number 1 on the R&B chart and number 11 on the pop chart.[49] The Orioles were perhaps the first of the many doo-wop groups who named themselves after birds.[50]

The sexual innuendo in the Orioles' songs was less disguised than in the vocal group music of the swing era. Their stage choreography was also more sexually explicit, and their songs were simpler and more emotionally direct. This new approach to sex in their performances did not target the white teen audience at first—when the Orioles took the stage, they were appealing directly to a young black audience,[51] with Sonny Til using his entire body to convey the emotion in the lyrics of their songs. He became a teen sex symbol for black girls, who reacted by screaming and throwing pieces of clothing onto the stage when he sang. Other young male vocalists of the era took note and adjusted their own acts accordingly.[45] The Orioles were soon displaced by newer groups who imitated these pioneers as a model for success.[52][53]

The Swallows began in the late 1940s as a group of Baltimore teenagers calling themselves the Oakaleers. One of the members lived across the street from Sonny Til, who went on to lead the Orioles, and their success inspired the Oakaleers to rename themselves the Swallows.[50] Their song "Will You Be Mine", released in 1951, reached number 9 on the US Billboard R&B chart.[54] In 1952, the Swallows released "Beside You", their second national hit, which peaked at number 10 on the R&B chart.[54]

Some Baltimore doo-wop groups were connected with street gangs, and a few members were active in both scenes, such as Johnny Page of the Marylanders.[55] As in all the major urban centers of the US, many of the teen gangs had their own street corner vocal groups in which they took great pride and which they supported fiercely. Competitive music and dance was a part of African American street culture, and with the success of some local groups, competition increased, leading to territorial rivalries among performers. Pennsylvania Avenue served as a boundary between East and West Baltimore, with the East producing the Swallows and the Cardinals and the Blentones, while the West was home to the Orioles and the Four Buddies.[56]

Baltimore vocal groups gathered at neighborhood record stores, where they practiced the latest hits in hopes that the store owners' connections with record companies and distributors might land them an audition. A King Records talent scout discovered the Swallows as they were rehearsing in Goldstick's record store. Sam Azrael's Super Music Store and Shaw's shoeshine parlor were also favored hangouts for Baltimore vocal groups; Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun auditioned the Cardinals at Azrael's. Some groups cut demos at local studios and played them for recording producers, with the aim of getting signed to a record deal.[56]

Chicago

[edit]The city of Chicago was outranked as a recording center in the United States only by New York City in the early years of the music recording industry. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, independent record labels gained control of the black record market from the major companies, and Chicago rose as one of the main centers for rhythm and blues music. This music was a vital source for the youth music called rock 'n' roll. In the mid-1950s, a number of rhythm and blues acts performing in the vocal ensemble style later known as doo-wop began to cross over from the R&B charts to mainstream rock 'n' roll.[57] The Chicago record companies took note of this trend and scouted for vocal groups from the city that they could sign to their labels.[58] The record labels, record distributors, and nightclub owners of Chicago all had a part in developing the vocal potential of the doo-wop groups, but Chicago doo-wop was "created and nourished" on the street corners of the city's lower-class neighborhoods.[59]

The Chicago doo-wop groups, like those in New York, started singing on street corners and practiced their harmonies in tiled bathrooms, hallways, and subways,[60] but because they came originally from the deep South, the home of gospel and blues music, their doo-wop sound was more influenced by gospel and blues.[61]

Vee-Jay Records and Chess Records were the main labels recording doo-wop groups in Chicago. Vee-Jay signed the Dells, the El Dorados, the Magnificents, and the Spaniels, all of whom achieved national chart hits in the mid-1950s. Chess signed the Moonglows, who had the most commercial success (seven Top 40 R&B hits, six of those Top Ten[62]) of the 1950s doo-wop groups,[63] and the Flamingos, who had national hits as well.[64]

Detroit

[edit]In 1945,[65] Joe Von Battle opened Joe's Record Shop at 3530 Hastings Street in Detroit; the store had the largest selection of rhythm and blues records in the city, according to a 1954 Billboard business survey. Battle, a migrant from Macon, Georgia, established his shop as the first black-owned business in the area, which remained primarily Jewish up to the late 1940s.[66] Young aspiring performers would gather there in hopes of being discovered by the leading independent record company owners who courted Battle to promote and sell records, as well as to find new talent at his shop and studio. Battle's record labels included JVB, Von, Battle, Gone, and Viceroy;[67][68] he also had subsidiary arrangements with labels such as King and Deluxe. He supplied Syd Nathan with many blues and doo-wop masters recorded in his primitive back-of-the-store studio from 1948 to 1954. As the pivotal recording mogul in the Detroit area, Battle was an important player in the independent label network.[69]

Jack and Devora Brown, a Jewish couple, founded Fortune Records in 1946 and recorded a variety of eccentric artists and sounds; in the mid-1950s they became champions of Detroit rhythm and blues, including the music of local doo-wop groups. Fortune's premier act was the Diablos, featuring the soaring tenor of lead vocalist Nolan Strong, a native of Alabama. The group's most notable hit was "The Wind".[70] Strong, like other R&B and doo-wop tenors of the time, was profoundly influenced by Clyde McPhatter, lead singer of the Dominoes and later of the Drifters. Strong himself made a lasting impression on the young Smokey Robinson, who went out of his way to attend Diablo shows.[71]

In late 1957, seventeen-year-old Robinson, fronting a Detroit vocal harmony group called the Matadors, met the producer Berry Gordy, who was beginning to take up new styles, including doo-wop.[72] Gordy wanted to promote a black style of music that would appeal to both the black and white markets, performed by black musicians with roots in gospel, R&B, or doo-wop. He sought artists who understood that the music had to be updated to appeal to a broader audience and attain greater commercial success.[73] Early recordings by Gordy's Tamla Records, founded several months before he established the Motown Record Corporation in January 1959,[74] were of either blues or doo-wop performances.[75]

"Bad Girl", a 1959 doo-wop single by Robinson's group, the Miracles, was the first single released (and the only one released by this group) on the Motown label—all previous singles from the company (and all those following from the group) were released on the Tamla label. Issued locally on the Motown Records label, it was licensed to and released nationally by Chess Records because the fledgling Motown Record Corporation did not, at that time, have national distribution.[76] "Bad Girl" was the group's first national chart hit,[77] reaching number 93 on the Billboard Hot 100.[78] Written by Miracles lead singer Smokey Robinson and Motown Records' president Berry Gordy, "Bad Girl" was the first of several of the Miracles' songs performed in the doo-wop style during the late 1950s.

Los Angeles

[edit]Doo-wop groups also formed on the west coast of the United States, especially in California, where the scene was centered in Los Angeles. Independent record labels owned by black entrepreneurs such as Dootsie Williams and John Dolphin recorded these groups, most of which had formed in high schools. One such group, the Penguins, included Cleveland "Cleve" Duncan and Dexter Tisby, former classmates at Fremont High School in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. They, along with Bruce Tate and Curtis Williams, recorded the song "Earth Angel" (produced by Dootsie Williams), which rose to number one on the R&B charts in 1954.[79]

Most of the Los Angeles doo-wop groups came out of the Fremont, Belmont, and Jefferson high schools. All of them were influenced by the Robins, a successful R&B group of the late 1940s and the 1950s who formed in San Francisco, or by other groups including the Flairs, the Flamingos (not the Chicago group) and the Hollywood Flames. Many other Los Angeles doo-wop groups of the time were recorded by Dootsie Williams' Dootone Records and by John Dolphin's Central Avenue record store, Dolphin's of Hollywood. These included the Calvanes,[80] the Crescendos, the Cuff Linx, the Cubans, the Dootones, the Jaguars, the Jewels, the Meadowlarks, the Silks, the Squires, the Titans, and the Up-Fronts. A few groups, such as the Platters and Rex Middleton's Hi-Fis, had crossover success.[81]

The Jaguars, from Fremont High School, was one of the first interracial vocal groups; it consisted of two African Americans, a Mexican American, and a Polish-Italian American. Doo-wop was popular with California Mexican Americans, who were attracted in the 1950s to its a capella vocals; the romantic style of the doo-wop groups appealed to them, as it was reminiscent of the traditional ballads and harmonies of Mexican folk music.[79][82]

In 1960, Art Laboe released one of the first oldies compilations, Memories of El Monte, on his record label, Original Sound. The record was a collection of classic doo-wop songs by bands that used to play at the dances Laboe organized at Legion Stadium in El Monte, California,[83] beginning in 1955. It included songs by local bands such as the Heartbeats and the Medallions. Laboe had become a celebrity in the Los Angeles area as a disc jockey for radio station KPOP, playing doo-wop and rhythm and blues broadcast from the parking lot of Scriverner's Drive-In on Sunset Boulevard.[84]

In 1962, Frank Zappa, with his friend Ray Collins, wrote the doo-wop song "Memories of El Monte". This was one of the first songs written by Zappa, who had been listening to Laboe's compilation of doo-wop singles. Zappa took the song to Laboe, who recruited the lead vocalist of the Penguins, Cleve Duncan, for a new iteration of the group, recorded it, and released it as a single on his record label.[84]

New York City

[edit]Early doo-wop music, dating from the late 1940s and early 1950s, was especially popular in the Northeast industrial corridor from New York to Philadelphia,[85] and New York City was the world capital of doo-wop.[86] There, African American groups such as the Ravens, the Drifters, the Dominoes, the Charts, and the so-called "bird groups", such as the Crows, the Sparrows, the Larks, and the Wrens, melded rhythm and blues with the gospel music they had grown up singing in church. Street singing was almost always a cappella; instrumental accompaniment was added when the songs were recorded.[85] The large numbers of blacks who had migrated to New York City as part of the Great Migration came mostly from Georgia, Florida, and the Carolinas. In the 1940s black youths in the city began to sing the rhythm and blues styling that came to be known as doo-wop.[87] Many of these groups were found in Harlem.[88]

Blacks were forced by legal and social segregation, as well as by the constraints of the built environment, to live in certain parts of New York City of the early 1950s. They identified with their own wards, street blocks and streets. Being effectively locked out of mainstream white society increased their social cohesion and encouraged creativity within the context of African American culture. Young singers formed groups and rehearsed their songs in public spaces: on street corners, apartment stoops, and subway platforms, in bowling alleys, school bathrooms, and pool halls, as well as at playgrounds and under bridges.[45]

Bobby Robinson, a native of South Carolina, was an independent record producer and songwriter in Harlem who helped popularize doo-wop music in the 1950s. He got into the music business in 1946 when he opened "Bobby's Record Shop" (later "Bobby's Happy House") on the corner of 125th Street[89][90] and Eighth Avenue, near the Apollo Theater, a noted venue for African-American performers. The Apollo held talent contests in which audience members indicated their favorites with applause. These were a major outlet for doo-wop performers to be discovered by record company talent scouts.[91] In 1951, Robinson started Robin Records, which later became Red Robin Records, and began recording doo-wop; he recorded the Ravens, the Mello-Moods, and many other doo-wop vocal groups.[92] He used the tiny shop to launch a series of record labels which released many hits in the US.[93] Robinson founded or co-founded Red Robin Records, Whirlin' Disc Records, Fury Records, Everlast Records, Fire Records and Enjoy Records.[94]

Arthur Godfrey's long-running (1946–1958) morning radio show on CBS, Talent Scouts, was a New York venue from which some doo-wop groups gained national exposure. In 1948, the Orioles, then known as the Vibra-Nairs, went to the city with Deborah Chessler, their manager and main songwriter, and appeared on the show. They won only third place, but Godfrey invited them back twice. Chessler leveraged a few demo recordings the group had cut, along with the recent radio exposure, to interest a distributor in marketing the group on an independent label. They cut six sides, one of which was a doo-wop ballad written by Chessler called "It's Too Soon to Know". It reached no. 1 on Billboard's national Most-Played Juke Box Race Records chart, and, in a first for a doo-wop song, the record crossed over to the mainstream pop chart, where it reached no. 13.[49]

The Du Droppers formed in Harlem in 1952. Members of the band were experienced gospel singers in ensembles dating to the 1940s, and were one of the oldest groups to record during the era. Among the Du Droppers' most enduring songs are "I Wanna Know" and "I Found Out (What You Do When You Go Round There)", which both reached number three on the Billboard R&B charts in 1953.

Frankie Lymon, lead vocalist of the Teenagers, was the first black teen idol who appealed to both black and white audiences. He was born in Harlem, where he began singing doo-wop songs with his friends on the streets. He joined a group, the Premiers, and helped members Herman Santiago and Jimmy Merchant rewrite a song they had composed to create "Why Do Fools Fall In Love", which won the group an audition with Gee Records. Santiago was too sick to sing lead on the day of the audition, consequently Lymon sang the lead on "Why Do Fools Fall in Love" instead, and the group was signed as the Teenagers with Lymon as lead singer. The song quickly charted as the number one R&B song in the United States and reached number six on the pop chart in 1956,[95][96] becoming the number one pop hit in the United Kingdom as well.[97]

The Willows, an influential street corner group from Harlem, were a model for many of the New York City doo-wop acts that rose after them. Their biggest hit was "Church Bells May Ring", featuring Neil Sedaka, then a member of the Linc-Tones, on chimes. It reached number 11 on the US R&B chart in 1956.[98][99]

Although they never had a national chart hit, the Solitaires, best known for their 1957 hit single "Walking Along", were one of the most popular vocal groups in New York in the late 1950s.[100]

The heyday of the girl group era began in 1957 with the success of two teen groups from the Bronx, the Chantels and the Bobbettes. The six girls in the Bobettes, aged eleven to fifteen, wrote and recorded "Mr. Lee", a novelty tune about a schoolteacher that was a national hit. The Chantels were the second African-American girl group to enjoy nationwide success in the US. The group was established in the early 1950s by five students, all of them born in the Bronx,[101] who attended the Catholic St. Anthony of Padua School in the Bronx, where they were trained to sing Gregorian Chants.[102] Their first recording was "He's Gone" (1958), which made them the first pop rock girl group to chart. Their second single, "Maybe" hit the charts, No. 15 on Billboard's Hot 100.[103]

In 1960, the Chiffons began as a trio of schoolmates at James Monroe High School in the Bronx.[104] Judy Craig, fourteen years old, was the lead singer, singing with Patricia Bennett and Barbara Lee, both thirteen. In 1962, the girls met songwriter Ronnie Mack at the after-school center; Mack suggested they add Sylvia Peterson, who had sung with Little Jimmy & the Tops, to the group. The group was named the Chiffons when recording and releasing their first single, "He's So Fine". Written by Mack, it was released on the Laurie Records label in 1963. "He's So Fine" hit No. 1 in the US, selling over one million copies.[105]

Public School 99, which sponsored evening talent shows, and Morris High School were centers of musical creativity in the Bronx during the doo-wop era. Arthur Crier, a leading figure in the doo-wop scene in the Morrissania neighborhood,[106] was born in Harlem and raised in the Bronx; his mother was from North Carolina. Crier was a founding member of a doo-wop group called the Five Chimes, one of several different groups with that name,[107] and sang bass with the Halos and the Mellows.[108] Many years later he observed that there was a shift in the music sung on the streets from gospel to secular rhythm and blues between 1950 and 1952.[109]

New York was also the capital of Italian doo-wop, and all its boroughs were home to groups that made successful records. The Crests were from the Lower East Side in Manhattan; Dion and the Belmonts, the Regents, and Nino and the Ebb Tides were from the Bronx; the Elegants from Staten Island; the Capris from Queens; the Mystics, the Neons, the Classics, and Vito & the Salutations from Brooklyn.[110]

Although Italians were a much smaller proportion of the Bronx's population in the 1950s than Jews and the Irish, only they had significant influence as rock 'n' roll singers. Young people of other ethnicities were listening to rock 'n' roll, but it was Italian Americans who established themselves in performing and recording the music.[111] While relationships between Italian Americans and African Americans in the Bronx were sometimes fraught, there were many instances of collaboration between them.[112]

Italian Americans kept African Americans out of their neighborhoods with racial boundary policing and fought against them in turf wars and gang battles, yet they adopted the popular music of African Americans, treated it as their own, and were an appreciative audience for black doo-wop groups.[113] Similarities in language idioms, masculine norms, and public comportment[114] made it possible for African American and Italian American young men to mingle easily when societal expectations did not interfere. These cultural commonalities allowed Italian Americans to appreciate the singing of black doo-woppers in deterritorialized spaces, whether on the radio, on records, at live concerts, or in street performances.[115] Dozens of neighborhood Italian groups formed, some of which recorded songs at Cousins Records, a record shop turned label, on Fordham Road.[116] Italian American groups from the Bronx released a steady stream of doo-wop songs, including "Teenager In Love" and "I Wonder Why" by Dion and the Belmonts, and "Barbara Ann" by the Regents.[111] Johnny Maestro, the Italian American lead singer of the interracial Bronx group the Crests, was the lead on the hit "Sixteen Candles". Maestro said that he became interested in R&B vocal group harmony listening to the Flamingos, the Harptones, and the Moonglows on Alan Freed's radio show on WINS in New York. Freed's various radio and stage shows had a crucial role in creating a market for Italian doo-wop.[115]

Philadelphia

[edit]Young black singers in Philadelphia helped create the doo-wop vocal harmony style developing in the major cities of the US during the 1950s. Early doo-wop groups in the city included the Castelles, the Silhouettes, the Turbans, and Lee Andrews & the Hearts. They were recorded by small independent rhythm and blues record labels, and occasionally by more established labels in New York. Most of these groups had limited success, scoring only one or two hit songs on the R&B charts. They had frequent personnel changes and often moved from label to label hoping to achieve another hit.[117]

The migration of blacks to Philadelphia from the southern states of the US, especially South Carolina and Virginia, had a profound effect not only on the city's demographics, but on its music and culture as well. During the Great Migration, the black population of Philadelphia increased to 250,000 by 1940. Hundreds of thousands of southern African Americans migrated to the metropolitan area, bringing their secular and religious folk music with them. After World War II, the black population of the metro grew to about 530,000 by 1960.[118]

Black doo-wop groups had a major role in the evolution of rhythm and blues in early 1950s Philadelphia. Groups like the Castelles and the Turbans helped develop the music with their tight harmonies, lush ballads, and distinctive falsettos. Many of these vocal groups got together in secondary schools such as West Philadelphia High School, and performed at neighborhood recreation centers and teen dances.[118] The Turbans, Philadelphia's first nationally charting R&B group,[119] formed in 1953 when they were in their teens. They signed with Herald Records and recorded "Let Me Show You (Around My Heart)" with its B side, "When We Dance", in 1955.[120] "When We Dance" became a national hit, rising to no. 3 on the R&B charts and reaching the Top 40 on the pop charts.[121]

The Silhouettes' crossover hit "Get a Job", released in 1957, reached number one on the pop and R&B charts in February 1958, while Lee Andrews & the Hearts had hits in 1957 and 1958 with "Teardrops", "Long Lonely Nights", and "Try the Impossible".[117]

Kae Williams, a Philadelphia deejay, record label owner and producer, managed the doo-wop groups Lee Andrews & the Hearts, the Sensations, who sold nearly a million records in 1961 with the song "Let Me In",[122] and the Silhouettes, who had a number 1 hit in 1958 with "Get a Job". After the nationally distributed Ember label acquired the rights to "Get a Job", Dick Clark began to play it on American Bandstand, and subsequently it sold over a million copies, topping the Billboard R&B singles chart and pop singles chart.[123]

Although American Bandstand's programming came to rely on the musical creations of black performers, the show marginalized black teens with exclusionary admissions policies until it moved to Los Angeles in 1964.[118] Featuring young whites dancing to music popularized by local deejays Georgie Woods and Mitch Thomas, with steps created by their black teenage listeners, Bandstand presented to its national audience an image of youth culture that erased the presence of black teenagers in Philadelphia's youth music scene.[124][125]

Broadcast from a warehouse on 46th and Market Street in West Philadelphia, most of American Bandstand's young dancers were Italian Americans who attended a nearby Catholic high school in South Philadelphia.[125] Like the rest of the entertainment industry, American Bandstand camouflaged the intrinsic blackness of the music in response to a national moral panic over rock 'n' roll's popularity with white teenagers, and the show's Italian American dancers and performers were deethnicized as "nice white kids", their Italian American youth identity submerged in whiteness.[126][127][128]

Dick Clark kept track of the national music scene through promoters and popular disc jockeys. In Philadelphia, he listened to Hy Lit, the lone white deejay at WHAT, and African American disc jockeys Georgie Woods and Douglas "Jocko" Henderson on WDAS. These were Philadelphia's two major black radio stations; they were black-oriented, but white-owned.[129][130]

The program director of WHAT, Charlie O'Donnell, hired Lit, who was Jewish, to deejay on the station in 1955, and Lit's career was launched. From there he went to WRCV and then around 1956 to WIBG, where over 70 percent of the radio audience in the listening area tuned in to his 6–10 p.m. program.[131]

Cameo Records and Parkway Records were major record labels based in Philadelphia from 1956 (Cameo) and 1958 (Parkway) to 1967 that released doo-wop records. In 1957, small Philadelphia record label XYZ had recorded "Silhouettes", a song by local group the Rays, which Cameo picked up for national distribution. It eventually reached number 3 on both the R&B Best Sellers chart and Billboard Top 100,[132][133] and also reached the top five on both the sales and airplay charts. It was the group's only top 40 hit.

Several white Philadelphia doo-wop groups also had chart-toppers; the Capris had a regional hit with "God Only Knows" in 1954.[134] In 1958, Danny & the Juniors had a number-one hit with "At the Hop" and their song "Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay" reached the top twenty. In 1961, the Dovells reached the number two spot with "Bristol Stomp", about teenagers in Bristol, Pennsylvania who were dancing a new step called "The Stomp".[117]

Jerry Blavat, a half-Jewish, half-Italian, popular deejay on Philadelphia radio, built his career hosting dances and live shows and gained a devoted local following. He soon had his own independent radio show, on which he introduced many doo-wop acts in the 1960s to a wide audience, including the Four Seasons, an Italian American group from Newark, New Jersey.[135][127]

Jamaica

[edit]The history of modern Jamaican music is relatively short. A sudden shift in its style began in the early 1950s with the importing of American rhythm and blues records to the island and the new availability of affordable transistor radios. Listeners whose tastes had been neglected by the lone Jamaican station at the time, RJR (Real Jamaican Radio), tuned into the R&B music being broadcast on the powerful nighttime signals of American AM radio stations,[136] especially WLAC in Nashville, WNOE in New Orleans, and WINZ in Miami.[137][138][139] On these stations Jamaicans could hear the likes of Fats Domino and doo-wop vocal groups.[140]

Jamaicans who worked as migrant agricultural workers in the southern US returned with R&B records, which sparked an active dance scene in Kingston.[138] In the late 1940s and early 1950s, many working-class Jamaicans who could not afford radios attended sound system dances, large outdoor dances featuring a deejay (selector) and his selection of records. Enterprising deejays used mobile sound systems to create impromptu street parties.[141] These developments were the principal means by which new American R&B records were introduced to a mass Jamaican audience.[136]

The opening by Ken Khouri of Federal Studios, Jamaica's first recording facility, in 1954, marked the beginning of a prolific recording industry and a thriving rhythm and blues scene in Jamaica.[138] In 1957, American performers including Rosco Gordon and the Platters performed in Kingston.[136] In late August 1957, the doo-wop group Lewis Lymon and the Teenchords arrived in Kingston as part of the "Rock-a-rama" rhythm and blues troupe for two days of shows at the Carib Theatre. The Four Coins, a Greek American doo-wop group from Pittsburgh, did a show in Kingston in 1958.[142]

Like their American exemplars, many Jamaican vocalists began their careers by practicing harmonies in groups on street corners, before moving on to the talent contest circuit that was the proving ground for new talent in the days before the rise of the first sound systems.[143]

In 1959, while he was a student at Kingston College, Dobby Dobson wrote the doo-wop song "Cry a Little Cry" in honor of his shapely biology teacher, and recruited a group of his schoolmates to back him on a recording of the song under the name Dobby Dobson and the Deltas on the Tip-Top label. It climbed to number one on the RJR charts, where it spent some six weeks.[144]

The harmonizing of the American doo-wop groups the Drifters and the Impressions served as a vocal model for a newly formed (1963) group, the Wailers, in which Bob Marley sang lead while Bunny Wailer sang high harmony and Peter Tosh sang low harmony.[137] The Wailers recorded an homage to doo-wop in 1965 with their version of Dion and the Belmonts' "A Teenager in Love".[143] Bunny Wailer cited Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the Platters, and the Drifters as early influences on the group. The Wailers covered Harvey and the Moonglows' 1958 doo-wop hit, "Ten Commandments of Love", on their debut album, Wailing Wailers, released in late 1965.[145] The same year, the Wailers cut the doo-wop song "Lonesome Feelings", with "There She Goes" on the B-side, as a single produced by Coxsone Dodd.[146]

Doo-wop and racial relations

[edit]The synthesis of music styles that evolved into what is now called rhythm and blues, previously labeled "race music" by the record companies, found a broad youth audience in the postwar years and helped to catalyze changes in racial relations in American society. By 1948, RCA Victor was marketing black music under the name "Blues and Rhythm". In 1949, Jerry Wexler, a reporter for Billboard magazine at the time, reversed the words and coined the name "Rhythm and Blues" to replace the term "Race Music" for the magazine's black music chart.[147]

One style of rhythm and blues was mostly vocal, with instrumental backing that ranged from a full orchestra to none. It was most often performed by a group, frequently a quartet, as in the black gospel tradition; utilizing close harmonies, this style was nearly always performed in a slow to medium tempo. The lead voice, usually one in the upper register, often sang over the driving, wordless chords of the other singers or interacted with them in a call-and-response exchange. Vocal harmony groups such as the Ink Spots embodied this style, the direct antecedent of doo-wop, which rose from inner city street corners in the mid-1950s and ranked high on the popular music charts between 1955 and 1959.[7]

Black and white young people both wanted to see popular doo-wop acts perform, and racially mixed groups of youths would stand on inner city street corners and sing doo-wop songs a capella. This angered white supremacists, who considered rhythm and blues and rock and roll a danger to America's youth.[148][149][150]

The development of rhythm and blues coincided with the issue of racial segregation becoming more socially contentious in American society, while the black leadership increasingly challenged the old social order. The white power structure in American society and some executives in the corporately controlled entertainment industry saw rhythm and blues, rooted in black culture, as obscene,[151] and considered it a threat to white youth, among whom the genre was becoming increasingly popular.[152]

Jewish influence in doo-wop

[edit]Jewish composers, musicians, and promoters had a prominent role in the transition to doo-wop and rock 'n' roll from jazz and swing in American popular music of the 1950s,[153] while Jewish businessmen founded many of the labels that recorded rhythm and blues during the height of the vocal group era.[154]

In the decade from 1944 to 1955, many of the most influential record companies specializing in "race" music—or "rhythm and blues", as it later came to be known—were owned or co-owned by Jews.[155] It was the small independent record companies that recorded, marketed, and distributed doo-wop music.[156] For example, Jack and Devora Brown, a Jewish couple in Detroit, founded Fortune Records in 1946, and recorded a variety of eccentric artists and sounds; in the mid-1950s they became champions of Detroit rhythm and blues, including the music of local doo-wop groups.[71]

A few other Jewish women were in the recording business, such as Florence Greenberg, who started the Scepter label in 1959, and signed the African American girl group, the Shirelles. The songwriting team of Goffin and King, who worked for Don Kirshner's Aldon music at 1650 Broadway (near the famed Brill Building at 1619),[157] offered Greenberg a song, "Will You Love Me Tomorrow", which was recorded by the Shirelles and rose to number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1961. During the early 1960s, Scepter was the most successful independent record label.[158]

Deborah Chessler, a young Jewish sales clerk interested in black music, became the manager and songwriter for the Baltimore doo-wop group the Orioles. They recorded her song "It's Too Soon to Know" and it reached no. 1 on Billboard's race records charts in November 1948.[159]

Some record company owners such as Herman Lubinsky had a reputation for exploiting black artists.[160] Lubinsky, who founded Savoy Records in 1942, produced and recorded the Carnations, the Debutantes, the Falcons, the Jive Bombers, the Robins, and many others. Although his entrepreneurial approach to the music business and his role as a middleman between black artists and white audiences created opportunities for unrecorded groups to pursue wider exposure,[160] he was reviled by many of the black musicians he dealt with.[161] Historians Robert Cherry and Jennifer Griffith maintain that regardless of Lubinsky's personal shortcomings, the evidence that he treated African American artists worse in his business dealings than other independent label owners did is unconvincing. They contend that in the extremely competitive independent record company business during the postwar era, the practices of Jewish record owners generally were more a reflection of changing economic realities in the industry than of their personal attitudes.[160]

New York rockers Lou Reed, Joey and Tommy Ramone, and Chris Stein were doo-wop fans, as were many other Jewish punks and proto-punks. Reed recorded his first lead vocals in 1962 on two doo-wop songs, "Merry Go Round" and "Your Love", which were not released at the time.[162] A few years later, Reed worked as a staff songwriter writing bubblegum and doo-wop songs in the assembly-line operation at Pickwick Records in New York.[163]

Doo-wop influence on punk and proto-punk rockers

[edit]The R&B and doo-wop music that informed early rock 'n' roll was racially appropriated in the 1970s just as blues-based rock had been in the 1950s and 1960s. Generic terms such as "Brill Building music" obscure the roles of the black producers, writers, and groups like the Marvelettes and the Supremes, who were performing similar music and creating hits for the Motown label, but were categorized as soul. According to ethnomusicologist Evan Rapport, before 1958 more than ninety percent of doo-wop performers were African-American, but the situation changed as large numbers of white groups began to enter the performance arena.[164]

This music was embraced by punk rockers in the 1970s, as part of a larger societal trend among white people in the US of romanticizing it as music that belonged to a simpler (in their eyes) time of racial harmony before the social upheaval of the 1960s. White Americans had a nostalgic fascination with the 1950s and early 1960s that entered mainstream culture beginning in 1969 when Gus Gossert started to broadcast early rock and roll and doo-wop songs on New York's WCBS-FM radio station. This trend reached its peak in racially segregated commercial productions such as American Graffiti, Happy Days, and Grease, which was double-billed with the Ramones' B-movie feature Rock 'n' Roll High School in 1979.[164]

Early punk rock adaptations of the 12-bar aab pattern associated with California surf or beach music, done within eight-, sixteen-, and twenty-four bar forms, were made by bands such as the Ramones, either as covers or as original compositions. Employing stylistic conventions of 1950s and 1960s doowop and rock and roll to signify the period referenced, some punk bands used call-and-response background vocals and doo-wop style vocables in songs, with subject matter following the example set by rock and roll and doo-wop groups of that era: teenage romance, cars, and dancing. Early punk rockers sometimes portrayed these nostalgic 1950s tropes with irony and sarcasm according to their own lived experiences, but they still indulged the fantasies evoked by the images.[165]

By 1963 and 1964, proto-punk rocker Lou Reed was working the college circuit, leading bands that played covers of three-chord hits by pop groups and "anything from New York with a classic doo-wop feel and a street attitude".[166]

Jonathan Richman, founder of the influential proto-punk band the Modern Lovers, cut the album Rockin' and Romance (1985) with acoustic guitar and doo-wop harmonies. His song "Down in Bermuda" for example, was directly influenced by "Down in Cuba" by the Royal Holidays. His album Modern Lovers 88 (1987), with doo-wop stylings and Bo Diddley rhythms, was recorded in acoustic trio format.[167]

Popularity

[edit]

Doo-wop groups achieved 1951 R&B chart hits with songs such as "Sixty Minute Man" by Billy Ward and His Dominoes, "Where Are You?" by the Mello-Moods, "The Glory of Love" by the Five Keys, and "Shouldn't I Know" by the Cardinals.

Doo-wop groups played a significant role in ushering in the rock and roll era when two big rhythm and blues hits by vocal harmony groups, "Gee" by the Crows, and "Sh-Boom" by the Chords, crossed over onto the pop music charts in 1954.[92] "Sh-Boom" is considered to have been the first rhythm-and-blues record to break into the top ten on the Billboard charts, reaching number 5; a few months later, a white group from Canada, the Crew Cuts, released their cover of the song, which reached number 1 and remained there for nine weeks.[168] This was followed by several other white artists covering doo-wop songs performed by black artists, all of which scored higher on the Billboard charts than did the originals. These include "Hearts of Stone" by the Fontaine Sisters (number 1), "At My Front Door" by Pat Boone (number 7), "Sincerely" by the McGuire Sisters (number 1), and "Little Darlin'" by the Diamonds (number 2). Music historian Billy Vera points out that these recordings are not considered to be doo-wop.[169]

"Only You" was released in June 1955 by pop group the Platters.[170] That same year the Platters had a number one pop chart hit with "The Great Pretender", released on 3 November.[171] In 1956, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers appeared on the Frankie Laine show in New York, which was televised nationally, performing their hit "Why Do Fools Fall in Love?". Frankie Laine referred to it as "rock and roll"; Lymon's extreme youth appealed to a young and enthusiastic audience. His string of hits included: "I Promise to Remember", "The ABC's of Love" and "I'm Not a Juvenile Delinquent".

Up tempo doo-wop groups such as the Monotones",[172] the Silhouettes, and the Marcels had hits that charted on Billboard. All-white doo-wop groups would appear and also produce hits: The Mello-Kings in 1957 with "Tonight, Tonight", the Diamonds in 1957 with the chart-topping cover song "Little Darlin'" (original song by an African American group), the Skyliners in 1959 with "Since I Don't Have You", the Tokens in 1961 with "The Lion Sleeps Tonight".

The peak of doo-wop might have been in the late 1950s; in the early 1960s the most notable hits were Dion's "Runaround Sue", "The Wanderer", "Lovers Who Wander" and "Ruby Baby"[173] and the Marcels' "Blue Moon".[174] There was a revival of the nonsense syllable form of doo-wop in the early 1960s, with popular records by the Marcels, the Rivingtons, and Vito & the Salutations. The genre reached the self-referential stage, with songs about the singers ("Mr. Bass Man" by Johnny Cymbal) and the songwriters ("Who Put the Bomp?" by Barry Mann), in 1961.

Doo-wop's influence

[edit]Other pop R&B groups, including the Coasters, the Drifters, the Midnighters, and the Platters, helped link the doo-wop style to the mainstream, and to the future sound of soul music. The style's influence is heard in the music of the Miracles, particularly in their early hits such as "Got A Job" (an answer song to "Get a Job"),[175] "Bad Girl", "Who's Loving You", "(You Can) Depend on Me", and "Ooo Baby Baby". Doo-wop was a precursor to many of the African-American musical styles seen today. Having evolved from pop, jazz and blues, doo-wop influenced many of the major rock and roll groups that defined the latter decades of the 20th century, and laid the foundation for many later musical innovations.

Doo-wop's influence continued in soul, pop, and rock groups of the 1960s, including the Four Seasons, girl groups, and vocal surf music performers such as the Beach Boys. In the Beach Boys' case, doo-wop influence is evident in the chord progression used on part of their early hit "Surfer Girl".[176][177] The Beach Boys later acknowledged their debt to doo-wop by covering the Regents' 1961 number 7 hit, "Barbara Ann" with their number 2 cover of the song in 1966.[178] In 1984, Billy Joel released "The Longest Time", a clear tribute to doo-wop music.[179]

Revivals

[edit]

Although the ultimate longevity of doo-wop has been disputed,[180][181] at various times in the 1970s–1990s the genre saw revivals, with artists being concentrated in urban areas, mainly in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Newark, and Los Angeles. Revival television shows and boxed CD sets such as the "Doo Wop Box" set 1–3 have rekindled interest in the music, the artists, and their stories.

Cruising with Ruben & the Jets, released in late 1968,[31] is a concept album of doo-wop music recorded by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention performing as a fictitious Chicano doo-wop band called Ruben & the Jets. In collaboration with Zappa, singer Ruben Guevara went on to start a real band called Ruben and the Jets.[182] An early notable revival of "pure" doo-wop occurred when Sha Na Na appeared at the Woodstock Festival. Soul group the Trammps recorded "Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart" in 1972.

Over the years other groups have had doo-wop or doo-wop-influenced hits, such as Robert John's 1972 version of "The Lion Sleeps Tonight", Darts successful revival of the doo-wop standards "Daddy Cool" and "Come Back My Love" in the late 1970s, Toby Beau's 1978 hit "My Angel Baby", and Billy Joel's 1984 hit "The Longest Time". Soul and funk bands such as Zapp released the single ("Doo Wa Ditty (Blow That Thing)/A Touch of Jazz (Playin' Kinda Ruff Part II)"). The last doo-wop record to reach the top ten on the U.S. pop charts was "It's Alright" by Huey Lewis and the News, a doo-wop adaptation of the Impressions' 1963 Top 5 smash hit. It reached number 7 on the U.S. Billboard Adult contemporary chart in June 1993. Much of the album had a doo-wop flavor. Another song from the By the Way sessions to feature a doo-wop influence was a cover of "Teenager In Love", originally recorded by Dion and the Belmonts. The genre would see another resurgence in popularity in 2018, with the release of the album "Love in the Wind" by Brooklyn-based band, the Sha La Das, produced by Thomas Brenneck for the Daptone Record label.

Doo-wop is popular among barbershoppers and collegiate a cappella groups due to its easy adaptation to an all-vocal form. Doo-wop experienced a resurgence in popularity at the turn of the 21st century with the airing of PBS's doo-wop concert programs: Doo Wop 50, Doo Wop 51, and Rock, Rhythm, and Doo Wop. These programs brought back, live on stage, some of the better known doo-wop groups of the past. In addition to the Earth Angels, doo-wop acts in vogue in the second decade of the 2000s range from the Four Quarters[183] to Street Corner Renaissance.[184] Bruno Mars and Meghan Trainor are two examples of current artists who incorporate doo-wop music into their records and live performances. Mars says he has "a special place in [his] heart for old-school music".[185]

The formation of the hip-hop scene beginning in the late 1970s strongly parallels the rise of the doo-wop scene of the 1950s, particularly mirroring it in the emergence of the urban street culture of the 1990s. According to Bobby Robinson, a well-known producer of the period:

Doo-wop originally started out as the black teenage expression of the '50s and rap emerged as the black teenage ghetto expression of the '70s. Same identical thing that started it – the doowop groups down the street, in hallways, in alleys and on the corner. They'd gather anywhere and, you know, doo-wop doowah da dadada. You'd hear it everywhere. So the same thing started with rap groups around '76 or so. All of a sudden, everywhere you turned you'd hear kids rapping. In the summertime, they'd have these little parties in the park. They used to go out and play at night and kids would be out there dancing. All of a sudden, all you could hear was, hip hop hit the top don't stop. It's kids – to a great extent mixed-up and confused – reaching out to express themselves. They were forcefully trying to express themselves and they made up in fantasy what they missed in reality.[186]

See also

[edit]- List of doo-wop musicians

- Scat singing

- Vocalese

- 50s progression, also known as the "Doo-wop" progression

- Boogie

References

[edit]- ^ [1] - Encyclopedia.com

- ^ Philip Gentry (2011). "Doo-Wop". In Emmett G. Price III; Tammy Lynn Kernodle; Horace Joseph Maxile (eds.). Encyclopedia of African American Music. ABC-CLIO. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1.

- ^ Stuart L. Goosman (17 July 2013). Group Harmony: The Black Urban Roots of Rhythm and Blues. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. x. ISBN 978-0-8122-0204-5.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ David Goldblatt (2013). "Nonsense in Public Places: Songs of Black Vocal Rhythm and Blues or Doo-Wop". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 71 (1). Wiley: 105. ISSN 0021-8529. JSTOR 23597540.

Doo-wop is characterized by simple lyrics, usually about the trials and ecstasies of young love, sung by a lead vocal against a background of repeated nonsense syllables.

- ^ a b Stuart L. Goosman (17 July 2013). Group Harmony: The Black Urban Roots of Rhythm and Blues. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-8122-0204-5.

- ^ a b Bernard Gendron (1986). "2: Theodor Adorno Meets the Cadillacs". In Tania Modleski (ed.). Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture. Indiana University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-253-35566-4.

- ^ Ralf von Appen, Markus Frei-Hauenschild (2015). "AABA, Refrain, Chorus, Bridge, Prechorus — Song Forms and their Historical Development". In: Samples. Online Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung/German Society for Popular Music Studies e.V., Ed. by Ralf von Appen, André Doehring and Thomas Phleps. Vol. 13, p. 6.

- ^ The Ink Spots. "The Ink Spots | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel, Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Records: 1940-1955, Record Research, Menomanee, Wisconsin, 1973 p.37

- ^ a b James A. Cosby (19 May 2016). Devil's Music, Holy Rollers and Hillbillies: How America Gave Birth to Rock and Roll. McFarland. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-1-4766-6229-9.

When done in swing time, early doo-wop became a popular form of rock and roll, and it was often slowed down to provide dance hits throughout the 1950s, and the genre was personified by successful groups like the Coasters and the Drifters.

- ^ Gage Averill (8 July 2003). John Shepherd (ed.). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Volume II: Performance and Production. Vol. 11, Close Harmony Singing. A&C Black. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8264-6322-7.

- ^ Gage Averill (20 February 2003). Four Parts, No Waiting: A Social History of American Barbershop Quartet. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-028347-6.

- ^ Larry Birnbaum (2013). Before Elvis: The Prehistory of Rock 'n' Roll. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8108-8638-4.

- ^ Gribin, Anthony j., and Matthew M. Schiff, The Complete Book of Doo-Wop, Collectables, Narberth, PA US, 2009 p. 17

- ^ Norman Abjorensen (25 May 2017). Historical Dictionary of Popular Music. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-5381-0215-2.

- ^ Jay Warner (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940s to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-634-09978-6.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ Virginia Dellenbaugh (30 March 2017). "From Earth Angel to Electric Lucifer: Castrati, Doo Wop and the Vocoder". In Julia Merrill (ed.). Popular Music Studies Today: Proceedings of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music 2017. Springer. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-658-17740-9.

- ^ Robert Pruter (1996). Doowop: The Chicago Scene. University of Illinois Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-252-06506-4.

- ^ a b Deena Weinstein (27 January 2015). Rock'n America: A Social and Cultural History. University of Toronto Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4426-0018-8.

- ^ a b "Where'd We Get the Name Doo-wop?". electricearl.com. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ The Five Satins. "The Five Satins | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Georgina Gregory (3 April 2019). Boy Bands and the Performance of Pop Masculinity. Taylor & Francis. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-429-64845-8.

- ^ Jay Warner (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940s to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 24]. ISBN 978-0-634-09978-6.

- ^ Anthony J. Gribin; Matthew M. Schiff (January 2000). The Complete Book of Doo-Wop. Krause. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-87341-829-4.

- ^ a b Colin A. Palmer; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (2006). Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History: the Black Experience in the Americas. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 1534. ISBN 978-0-02-865820-9.

- ^ a b Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 11 – Big Rock Candy Mountain: Early rock 'n' roll vocal groups & Frank Zappa" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 5.

- ^ "Shep & the Limelites Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ The Jive Five. "The Jive Five | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Reiland Rabaka (3 May 2016). Civil Rights Music: The Soundtracks of the Civil Rights Movement. Lexington Books. p. 127–128. ISBN 978-1-4985-3179-5.

- ^ Simone Cinotto (1 April 2014). Making Italian America: Consumer Culture and the Production of Ethnic Identities. Fordham University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8232-5626-6.

- ^ Brock Helander (1 January 2001). The Rockin' 60s: The People Who Made the Music. Schirmer Trade Books. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-85712-811-9.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ Steve Sullivan (4 October 2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. Scarecrow Press. p. 616. ISBN 978-0-8108-8296-6.

- ^ Greg Bower (27 January 2014). "Doo-wop". In Lol Henderson; Lee Stacey (eds.). Encyclopedia of Music in the 20th Century. Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-135-92946-6.

- ^ Simone Cinotto (1 April 2014). Making Italian America: Consumer Culture and the Production of Ethnic Identities. Fordham University Press. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0-8232-5626-6.

- ^ Hinckley, David (29 April 2013). "Lillian Leach Boyd, singer for The Mellows, dead at 76". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013.

- ^ Reebee Garofalo (2001). "VI. Off the Charts". In Rachel Rubin Jeffrey Paul Melnick (ed.). American Popular Music: New Approaches to the Twentieth Century. Amherst: Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 125. ISBN 1-55849-268-2.

- ^ Joe Sasfy (21 November 1984). "Doo-Wop Harmony". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Staff (12 June 1985). "Comeback On 'Chitlin Circuit'". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ a b c John Michael Runowicz (2010). Forever Doo-wop: Race, Nostalgia, and Vocal Harmony. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-1-55849-824-2.

- ^ Vladimir Bogdanov; Chris Woodstra; Stephen Thomas Erlewine (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Backbeat Books. p. 1306. ISBN 978-0-87930-653-3.

- ^ Michael Olesker (1 November 2013). Front Stoops in the Fifties: Baltimore Legends Come of Age. JHU Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-4214-1161-3.

- ^ Colin Larkin (27 May 2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Omnibus Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ a b Albin Zak (4 October 2012). I Don't Sound Like Nobody: Remaking Music in 1950s America. University of Michigan Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-472-03512-0.

- ^ a b Rick Simmons (8 August 2018). Carolina Beach Music Encyclopedia. McFarland. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-1-4766-6767-6.

- ^ Steve Sullivan (4 October 2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. Scarecrow Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-8108-8296-6.

- ^ Chuck Mancuso; David Lampe (1996). Popular Music and the Underground: Foundations of Jazz, Blues, Country, and Rock, 1900-1950. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-8403-9088-2.

- ^ Lawrence Pitilli (2 August 2016). Doo-Wop Acappella: A Story of Street Corners, Echoes, and Three-Part Harmonies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-4422-4430-6.

- ^ a b Jay Warner (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940s to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-634-09978-6.

- ^ Stuart L. Goosman (9 March 2010). Group Harmony: The Black Urban Roots of Rhythm and Blues. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8122-2108-4.

- ^ a b Ward, Brian (1998). Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness, and Race. University of California Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-520-21298-3.

- ^ Johnny Keys (15 January 2019). "Du-Wop". In Theo Cateforis (ed.). The Rock History Reader. Taylor & Francis. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-315-39480-0.

- ^ Robert Pruter (1996). Doowop: The Chicago Scene. University of Illinois Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-252-06506-4.

- ^ Pruter 1996, pp. 2, 10

- ^ Pruter 1996, pp. 2, 17

- ^ Anthony J. Gribin; Matthew M. Schiff (2000). The Complete Book of Doo-Wop. Krause. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-87341-829-4.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel, The Billboard Book of TOP 40 R&B and Hip Hop Hits, Billboard Books, New York 2006, p. 407

- ^ John Collis (15 October 1998). The Story of Chess Records. Bloomsbury USA. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-58234-005-0.

- ^ Clark "Bucky" Halker (2004). "Rock Music". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Marsha Music (5 June 2017). "Joe's Record Shop". In Joel Stone (ed.). Detroit 1967: Origins, Impacts, Legacies. Wayne State University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8143-4304-3.

- ^ Tony Fletcher (2017). In the Midnight Hour: The Life & Soul of Wilson Pickett. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-025294-6.

- ^ Lars Bjorn; Jim Gallert (2001). Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit, 1920-60. University of Michigan Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-472-06765-6.

- ^ Edward M. Komara (2006). Encyclopedia of the Blues. Psychology Press. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-415-92699-7.

- ^ John Broven (11 August 2011). Record Makers and Breakers: Voices of the Independent Rock 'n' Roll Pioneers. University of Illinois Press. pp. 135, 321. ISBN 978-0-252-09401-9.

- ^ Brian Ward (6 July 1998). Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness, and Race Relations. University of California Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-520-21298-5.

- ^ a b M. L. Liebler; S.R. Boland (2016). "3: The Pre-Motown Sounds". Heaven was Detroit: From Jazz to Hip-hop and Beyond. Wayne State University Press. pp. 100–104. ISBN 978-0-8143-4122-3.

- ^ Andrew Flory (30 May 2017). I Hear a Symphony: Motown and Crossover R&B. University of Michigan Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-472-03686-8.

- ^ Joe Stuessy; Scott David Lipscomb (2006). Rock and Roll: Its History and Stylistic Development. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-13-193098-8.

- ^ Lee Cotten (1989). The Golden Age of American Rock 'n Roll. Pierian Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-9646588-4-4.

- ^ Alex MacKenzie (2009). The Life and Times of the Motown Stars. Together Publications LLP. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-84226-014-2.

- ^ Colin Larkin (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Sixties Music. Virgin. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-7535-0149-8.

- ^ Bill Dahl (28 February 2011). Motown: The Golden Years: More than 100 rare photographs. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-4402-2557-4.

- ^ Rick Simmons (8 August 2018). Carolina Beach Music Encyclopedia. McFarland. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-4766-6767-6.

- ^ a b Anthony Macías (11 November 2008). Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935–1968. Duke University Press. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-0-8223-8938-5.

- ^ Mitch Rosalsky (2002). Encyclopedia of Rhythm & Blues and Doo-Wop Vocal Groups. Scarecrow Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8108-4592-3.

- ^ Barney Hoskyns (2009). Waiting for the Sun: A Rock 'n' Roll History of Los Angeles. Backbeat Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-87930-943-5.

- ^ Rubén Funkahuatl Guevara (13 April 2018). Confessions of a Radical Chicano Doo-Wop Singer. University of California Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-520-96966-7.

- ^ Barry Miles (1970). Zappa. Grove Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780802142153.

- ^ a b Webre, Jude P. (14 February 2020). "Memories of El Monte: Art Laboe's Charmed Life on the Air". In Guzmán, Romeo; Fragoza, Carribean; Cummings, Alex Sayf; Reft, Ryan (eds.). East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte. Rutgers University Press. pp. 227–231. ISBN 978-1-978805-48-4.

- ^ a b Albrecht, Robert (15 March 2019). "Doo-wop Italiano: Towards an understanding and appreciation of Italian-American vocal groups of the late 1950s and early 1960s". Popular Music and Society. 42 (2): 3. doi:10.1080/03007766.2017.1414663. S2CID 191844795. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Anthony J. Gribin; Matthew M. Schiff (2000). The Complete Book of Doo-wop. Krause. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-87341-829-4.

- ^ Dick Weissman; Richard Weissman (2005). "New York and the Doo-wop Groups". Blues: The Basics. Psychology Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-415-97068-6.

- ^ Arnold Shaw (1978). Honkers and Shouters: The Golden Years of Rhythm and Blues. Macmillan. p. xix. ISBN 978-0-02-610000-7.

- ^ John Eligon (21 August 2007). "An Old Record Shop May Fall Victim to Harlem's Success (Published 2007)". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Christopher Morris. "Music entrepreneur Bobby Robinson dies at 93". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011.

- ^ Albin Zak (4 October 2012). I Don't Sound Like Nobody: Remaking Music in 1950s America. University of Michigan Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-472-03512-0.

- ^ a b Dave Headlam (2002). "Appropriations of blues and gospel in popular music". In Allan Moore; Jonathan Cross (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music. Cambridge University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-521-00107-6.

- ^ David Hinckley (8 January 2011). "Harlem legend dead Bobby Robinson, owner of Happy House on 125th St". New York Daily News. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Alan B. Govenar (2010). Lightnin' Hopkins: His Life and Blues. Chicago Review Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-55652-962-7.

- ^ Shirelle Phelps, ed. (August 1999). Contemporary Black Biography. Gale Research Incorporated. pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-0-7876-2419-4.

- ^ Jessie Carney Smith (1 December 2012). Black Firsts: 4,000 Ground-Breaking and Pioneering Historical Events. Visible Ink Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-57859-424-5.

- ^ Peter Besel (2 December 2018). "Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers (1954–1957)". Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "The Willows, "Church Bells May Ring" Chart Positions". Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Cousin Bruce Morrow; Rich Maloof (2007). Doo Wop: The Music, the Times, the Era. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4027-4276-7.

- ^ Marv Goldberg. "The Solitaires". Marv Goldberg's R&B Notebooks. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

While never achieving the national stature of many of their contemporaries, the Solitaires managed to outlast most of them in a career that saw them as one of the top vocal groups on the New York scene.

- ^ Frank W. Hoffmann (2005). Rhythm and Blues, Rap, and Hip-hop. Infobase Publishing. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8160-6980-4.

- ^ Sheila Weller (8 April 2008). Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon--And the Journey of a Generation. Simon and Schuster. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4165-6477-5.

- ^ Clay Cole (October 2009). Sh-Boom!: The Explosion of Rock 'n' Roll (1953–1968). Wordclay. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-60037-638-2.

- ^ Jay Warner (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940s to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-634-09978-6.

- ^ Joseph Murrells (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 157. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ Mark Naison (2004). "From Doo Wop to Hip Hop: The Bittersweet Odyssey of African-Americans in the South Bronx | Socialism and Democracy". Socialism and Democracy. 18 (2). Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Philip Groia (1983). They All Sang on the Corner: A Second Look at New York City's Rhythm and Blues Vocal Groups. P. Dee Enterprises. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-9612058-0-5.

- ^ Carolyn McLaughlin (21 May 2019). South Bronx Battles: Stories of Resistance, Resilience, and Renewal. University of California Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-520-96380-1.

- ^ Arthur Crier (25 September 2015). "Interview with the Bronx African American History Project". Oral Histories. Fordham University: 10. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Simone Cinotto (1 April 2014). "Italian Doo-Wop: Sense of place, Politics of Style, and Racial Crossovers in Postwar New York City". Making Italian America: Consumer Culture and the Production of Ethnic Identities. Fordham University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8232-5626-6.

- ^ a b Mark Naison (29 January 2019). "Italian Americans in Bronx Doo Wop-The Glory and the Paradox". Occasional Essays. Fordham University: 2–4. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ John Gennari (18 March 2017). "Who Put the Wop in Doo-wop?". Flavor and Soul: Italian America at Its African American Edge. University of Chicago Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-226-42832-1.

- ^ Donald Tricarico (24 December 2018). Guido Culture and Italian American Youth: From Bensonhurst to Jersey Shore. Springer. p. 38. ISBN 978-3-030-03293-7.

- ^ John Gennari (18 March 2017). Flavor and Soul: Italian America at Its African American Edge. University of Chicago Press. pp. 22–23, 48, 71, 90–95. ISBN 978-0-226-42832-1.

- ^ a b Simone Cinotto (1 April 2014). "Italian Doo-Wop: Sense of place, Politics of Style, and Racial Crossovers in Postwar New York City". Making Italian America: Consumer Culture and the Production of Ethnic Identities. Fordham University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8232-5626-6.

- ^ Jay Warner (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940s to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-634-09978-6.

- ^ a b c Jack McCarthy (2016). "Doo Wop". philadelphiaencyclopedia.org. Rutgers University. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Emmett G. Price III; Tammy Kernodle; Horace J. Maxile, Jr., eds. (17 December 2010). Encyclopedia of African American Music. ABC-CLIO. p. 727. ISBN 978-0-313-34200-4.

- ^ Nick Talevski (7 April 2010). Rock Obituaries: Knocking On Heaven's Door. Music Sales. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-85712-117-2.

- ^ "The Turbans on Herald Records". archive.org. Internet Archive. 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Bob Leszczak (10 October 2013). Who Did It First?: Great Rhythm and Blues Cover Songs and Their Original Artists. Scarecrow Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8108-8867-8.

- ^ Jay Warner (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940s to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-634-09978-6.

- ^ John Jackson (3 June 1999). American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock 'n' Roll Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-19-028490-9.

- ^ Matthew F. Delmont (22 February 2012). The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock 'n' Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia. University of California Press. pp. 15–16, 21. ISBN 978-0-520-95160-0.

- ^ a b John A. Jackson (23 September 2004). A House on Fire: The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia Soul. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-19-514972-2.

- ^ George J. Leonard; Pellegrino D'Acierno (1998). The Italian American Heritage: A Companion to Literature and Arts. Taylor & Francis. pp. 437–438. ISBN 978-0-8153-0380-0.

- ^ a b John Gennari (27 September 2017). "Groovin': A Riff on Italian Americans in Popular Music and Jazz". In William J. Connell; Stanislao G. Pugliese (eds.). The Routledge History of Italian Americans. Taylor & Francis. p. 580. ISBN 978-1-135-04670-5.

- ^ Donald Tricarico (24 December 2018). Guido Culture and Italian American Youth: From Bensonhurst to Jersey Shore. Springer. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-3-030-03293-7.

- ^ John Jackson (3 June 1999). American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock 'n' Roll Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-028490-9.