Sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are also known as shakeholes, and to openings where surface water enters into underground passages known as ponor, swallow hole or swallet.[1][2][3][4] A cenote is a type of sinkhole that exposes groundwater underneath.[4] Sink, and stream sink are more general terms for sites that drain surface water, possibly by infiltration into sediment or crumbled rock.[2]

Most sinkholes are caused by karst processes – the chemical dissolution of carbonate rocks, collapse or suffosion processes.[1][5] Sinkholes are usually circular and vary in size from tens to hundreds of meters both in diameter and depth, and vary in form from soil-lined bowls to bedrock-edged chasms. Sinkholes may form gradually or suddenly, and are found worldwide.[2][1]

Formation

[edit]

Natural processes

[edit]Sinkholes may capture surface drainage from running or standing water, but may also form in high and dry places in specific locations. Sinkholes that capture drainage can hold it in large limestone caves. These caves may drain into tributaries of larger rivers.[6][7]

The formation of sinkholes involves natural processes of erosion[8] or gradual removal of slightly soluble bedrock (such as limestone) by percolating water, the collapse of a cave roof, or a lowering of the water table.[9] Sinkholes often form through the process of suffosion.[10] For example, groundwater may dissolve the carbonate cement holding the sandstone particles together and then carry away the lax particles, gradually forming a void.

Occasionally a sinkhole may exhibit a visible opening into a cave below. In the case of exceptionally large sinkholes, such as the Minyé sinkhole in Papua New Guinea or Cedar Sink at Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, an underground stream or river may be visible across its bottom flowing from one side to the other.

Sinkholes are common where the rock below the land surface is limestone or other carbonate rock, salt beds, or in other soluble rocks, such as gypsum,[11] that can be dissolved naturally by circulating ground water. Sinkholes also occur in sandstone and quartzite terrains.

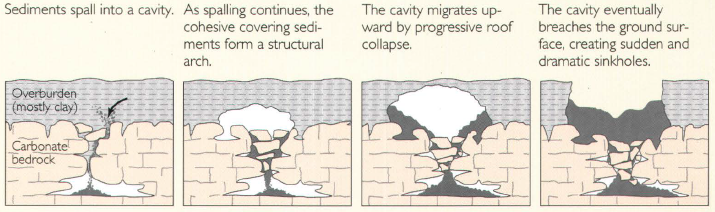

As the rock dissolves, spaces and caverns develop underground. These sinkholes can be dramatic, because the surface land usually stays intact until there is not enough support. Then, a sudden collapse of the land surface can occur.[12]

Space and planetary bodies

[edit]On 2 July 2015, scientists reported that active pits, related to sinkhole collapses and possibly associated with outbursts, were found on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko by the Rosetta space probe.[13][14]

Artificial processes

[edit]

Collapses, commonly incorrectly labeled as sinkholes, also occur due to human activity, such as the collapse of abandoned mines and salt cavern storage in salt domes in places like Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas, in the United States. More commonly, collapses occur in urban areas due to water main breaks or sewer collapses when old pipes give way. They can also occur from the overpumping and extraction of groundwater and subsurface fluids.

Sinkholes can also form when natural water drainage patterns are changed and new water diversion systems are developed. Some sinkholes form when the land surface is changed, such as when industrial and runoff storage ponds are created; the substantial weight of the new material can trigger a collapse of the roof of an existing void or cavity in the subsurface, resulting in development of a sinkhole.

Classification

[edit]Solution sinkholes

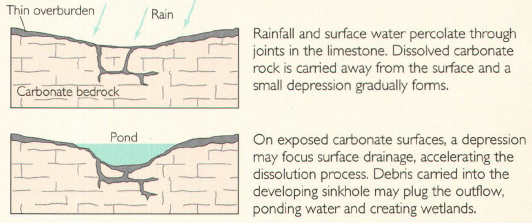

[edit]Solution or dissolution sinkholes form where water dissolves limestone under a soil covering. Dissolution enlarges natural openings in the rock such as joints, fractures, and bedding planes. Soil settles down into the enlarged openings forming a small depression at the ground surface.[15]

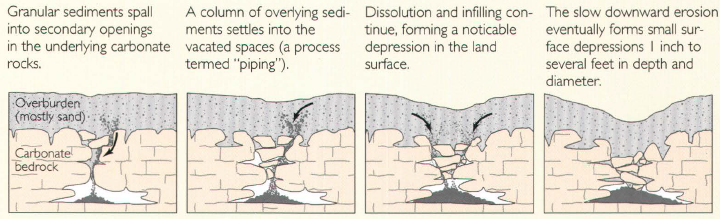

Cover-subsidence sinkholes

[edit]Cover-subsidence sinkholes form where voids in the underlying limestone allow more settling of the soil to create larger surface depressions.[15]

Cover-collapse sinkholes

[edit]Cover-collapse sinkholes or "dropouts" form where so much soil settles down into voids in the limestone that the ground surface collapses. The surface collapses may occur abruptly and cause catastrophic damages. New sinkhole collapses can also form when human activity changes the natural water-drainage patterns in karst areas.[15]

Pseudokarst sinkholes

[edit]Pseudokarst sinkholes resemble karst sinkholes but are formed by processes other than the natural dissolution of rock.[16]: 4

Human accelerated sinkholes

[edit]

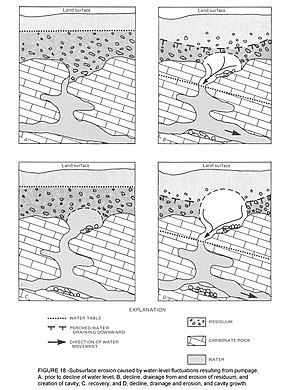

The U.S. Geological Survey notes that "It is a frightening thought to imagine the ground below your feet or house suddenly collapsing and forming a big hole in the ground."[15] Human activities can accelerate collapses of karst sinkholes, causing collapse within a few years that would normally evolve over thousands of years under natural conditions.[17]: 2 [18][16]: 1 and 92 Soil-collapse sinkholes, which are characterized by the collapse of cavities in soil that have developed where soil falls down into underlying rock cavities, pose the most serious hazards to life and property. Fluctuation of the water level accelerates this collapse process. When water rises up through fissures in the rock, it reduces soil cohesion. Later, as the water level moves downward, the softened soil seeps downwards into rock cavities. Flowing water in karst conduits carries the soil away, preventing soil from accumulating in rock cavities and allowing the collapse process to continue.[19]: 52–53

Induced sinkholes occur where human activity alters how surface water recharges groundwater. Many human-induced sinkholes occur where natural diffused recharge is disturbed and surface water becomes concentrated. Activities that can accelerate sinkhole collapses include timber removal, ditching, laying pipelines, sewers, water lines, storm drains, and drilling. These activities can increase the downward movement of water beyond the natural rate of groundwater recharge.[17]: 26–29 The increased runoff from the impervious surfaces of roads, roofs, and parking lots also accelerate man-induced sinkhole collapses.[16]: 8

Some induced sinkholes are preceded by warning signs, such as cracks, sagging, jammed doors, or cracking noises, but others develop with little or no warning.[17]: 32–34 However, karst development is well understood, and proper site characterization can avoid karst disasters. Thus most sinkhole disasters are predictable and preventable rather than "acts of God".[20]: xii [16]: 17 and 104 The American Society of Civil Engineers has declared that the potential for sinkhole collapse must be a part of land-use planning in karst areas. Where sinkhole collapse of structures could cause loss of life, the public should be made aware of the risks.[19]: 88

The most likely locations for sinkhole collapse are areas where there is already a high density of existing sinkholes. Their presence shows that the subsurface contains a cave system or other unstable voids.[21] Where large cavities exist in the limestone large surface collapses can occur, such the Winter Park, Florida sinkhole collapse.[16]: 91–92 Recommendations for land uses in karst areas should avoid or minimize alterations of the land surface and natural drainage.[17]: 36

Since water level changes accelerate sinkhole collapse, measures must be taken to minimize water level changes. The areas most susceptible to sinkhole collapse can be identified and avoided.[19]: 88 In karst areas the traditional foundation evaluations (bearing capacity and settlement) of the ability of soil to support a structure must be supplemented by geotechnical site investigation for cavities and defects in the underlying rock.[19]: 113 Since the soil/rock surface in karst areas are very irregular the number of subsurface samples (borings and core samples) required per unit area is usually much greater than in non-karst areas.[19]: 98–99

In 2015, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated the cost for repairs of damage arising from karst-related processes as at least $300 million per year over the preceding 15 years, but noted that this may be a gross underestimate based on inadequate data.[22] The greatest amount of karst sinkhole damage in the United States occurs in Florida, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania.[23] The largest recent sinkhole in the USA is possibly one that formed in 1972 in Montevallo, Alabama, as a result of man-made lowering of the water level in a nearby rock quarry. This "December Giant" or "Golly Hole" sinkhole measures 130 m (425 ft) long, 105 m (350 ft) wide and 45 m (150 ft) deep.[17]: 1–2 [19]: 61–63 [24]

Other areas of significant karst hazards include the Ebro Basin in northern Spain; the island of Sardinia; the Italian peninsula; the Chalk areas in southern England; Sichuan, China; Jamaica; France;[25]Croatia;[26] Bosnia and Herzegovina; Slovenia; and Russia, where one-third of the total land area is underlain by karst.[27]

Occurrence

[edit]

Sinkholes tend to occur in karst landscapes.[12] Karst landscapes can have up to thousands of sinkholes within a small area, giving the landscape a pock-marked appearance. These sinkholes drain all the water, so there are only subterranean rivers in these areas. Examples of karst landscapes with numerous massive sinkholes include Khammouan Mountains (Laos) and Mamo Plateau (Papua New Guinea).[28][29] The largest known sinkholes formed in sandstone are Sima Humboldt and Sima Martel in Venezuela.[29]

Some sinkholes form in thick layers of homogeneous limestone. Their formation is facilitated by high groundwater flow, often caused by high rainfall; such rainfall causes formation of the giant sinkholes in the Nakanaï Mountains, on the New Britain island in Papua New Guinea.[30] Powerful underground rivers may form on the contact between limestone and underlying insoluble rock, creating large underground voids.

In such conditions, the largest known sinkholes of the world have formed, like the 662-metre-deep (2,172 ft) Xiaozhai Tiankeng (Chongqing, China), giant sótanos in Querétaro and San Luis Potosí states in Mexico and others.[29][31]

Unusual processes have formed the enormous sinkholes of Sistema Zacatón in Tamaulipas (Mexico), where more than 20 sinkholes and other karst formations have been shaped by volcanically heated, acidic groundwater.[32][33] This has produced not only the formation of the deepest water-filled sinkhole in the world—Zacatón—but also unique processes of travertine sedimentation in upper parts of sinkholes, leading to sealing of these sinkholes with travertine lids.[33]

The U.S. state of Florida in North America is known for having frequent sinkhole collapses, especially in the central part of the state. Underlying limestone there is from 15 to 25 million years old. On the fringes of the state, sinkholes are rare or non-existent; limestone there is around 120,000 years old.[34]

The Murge area in southern Italy also has numerous sinkholes. Sinkholes can be formed in retention ponds from large amounts of rain.[35]

On the Arctic seafloor, methane emissions have caused large sinkholes to form.[36][37]

Human uses

[edit]Sinkholes have been used for centuries as disposal sites for various forms of waste. A consequence of this is the pollution of groundwater resources, with serious health implications in such areas.[38][39]

The Maya civilization sometimes used sinkholes in the Yucatán Peninsula (known as cenotes) as places to deposit precious items and human sacrifices.[40]

When sinkholes are very deep or connected to caves, they may offer challenges for experienced cavers or, when water-filled, divers. Some of the most spectacular are the Zacatón cenote in Mexico (the world's deepest water-filled sinkhole), the Boesmansgat sinkhole in South Africa, Sarisariñama tepuy in Venezuela, the Sótano del Barro in Mexico, and in the town of Mount Gambier, South Australia. Sinkholes that form in coral reefs and islands that collapse to enormous depths are known as blue holes and often become popular diving spots.[41]

Local names

[edit]

Large and visually unusual sinkholes have been well known to local people since ancient times. Nowadays sinkholes are grouped and named in site-specific or generic names. Some examples of such names are listed below.[42]

- Aven – In the south of France (this name means pit cave in the Occitan language).

- Black holes (not to be confused with cosmic black holes) – This term refers to a group of unique, round, water-filled pits in the Bahamas. These formations seem to be dissolved in carbonate mud from above, by the sea water. The dark color of the water is caused by a layer of phototropic microorganisms concentrated in a dense, purple colored layer at 15 to 20 m (49 to 66 ft) depth; this layer "swallows" the light. Metabolism in the layer of microorganisms causes heating of the water. One of them is the Black Hole of Andros.[43]

- Blue holes – This name was initially given to the deep underwater sinkholes of the Bahamas but is often used for any deep water-filled pits formed in carbonate rocks. The name originates from the deep blue color of water in these sinkholes, which is created by the high clarity of the water and the great depth of the sinkholes; only the deep blue color of the visible spectrum can penetrate such depth and return after reflection.

- Cenote – This refers to the characteristic water-filled sinkholes in the Yucatán Peninsula, Belize and some other regions. Many cenotes have formed in limestone deposited in shallow seas created by the Chicxulub meteorite's impact.

- Dolina – Slovenian toponym internationally used for karst sinkholes. The original meaning is "valley" or "dale".[44]

- Foiba – Friulan Italian dialect word (from the Latin fŏvea: "pit" or "chasm"). The name is given to sinkholes in the frontier zone between the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Croatia and Slovenia, in the Karst Plateau.

- Sótanos – This name is given to several giant pits in several states of Mexico.

- Tiankengs – These are extremely large sinkholes, typically deeper and wider than 250 m (820 ft), with mostly vertical walls, most often created by the collapse of caverns. The term means sky holes in Chinese; many of this largest type of sinkhole are located in China.[20]: 64

- Tomo – This term is used in New Zealand karst country to describe sinkholes.[45]

- Vrtača, ponikva, dolac, dô – South Slavic terms for sinkhole.[44][46]

Piping pseudokarst

[edit]The 2010 Guatemala City sinkhole formed suddenly in May of that year; torrential rains from Tropical Storm Agatha and a bad drainage system were blamed for its creation. It swallowed a three-story building and a house; it measured approximately 20 m (66 ft) wide and 30 m (98 ft) deep.[47] A similar hole had formed nearby in February 2007.[48][49][50]

This large vertical hole is not a true sinkhole, as it did not form via the dissolution of limestone, dolomite, marble, or any other water-soluble rock.[51][52] Instead, they are examples of "piping pseudokarst", created by the collapse of large cavities that had developed in the weak, crumbly Quaternary volcanic deposits underlying the city. Although weak and crumbly, these volcanic deposits have enough cohesion to allow them to stand in vertical faces and to develop large subterranean voids within them. A process called "soil piping" first created large underground voids, as water from leaking water mains flowed through these volcanic deposits and mechanically washed fine volcanic materials out of them, then progressively eroded and removed coarser materials. Eventually, these underground voids became large enough that their roofs collapsed to create large holes.[51]

Crown hole

[edit]A crown hole is subsidence due to subterranean human activity, such as mining and military trenches.[53][54] Examples have included, instances above World War I trenches in Ypres, Belgium; near mines in Nitra, Slovakia;[55] a limestone quarry in Dudley, England;[55][56] and above an old gypsum mine in Magheracloone, Ireland.[54]

Notable examples

[edit]

Some of the largest sinkholes in the world are:[29]

Africa

[edit]- Boesmansgat – South African freshwater sinkhole, approximately 290 m (950 ft) deep.[57]

- Lake Kashiba – Zambia. About 3.5 hectares (8.6 acres) in area and about 100 m (330 ft) deep.

Asia

[edit]- Blue Hole – Dahab, Egypt. A round sinkhole or blue hole, 130 m (430 ft) deep. It includes an archway leading out to the Red Sea at 60 m (200 ft), which has been the site for many freediving and scuba attempts, the latter often fatal.[58]

- Akhayat sinkhole is in Mersin Province, Turkey. Its dimensions are about 150 m (490 ft) in diameter with a maximum depth of 70 m (230 ft).

- Well of Barhout – Yemen. A 112-metre (367 ft) deep pit cave in Al-Mahara.

- Bimmah Sinkhole (Hawiyat Najm, the Falling Star Sinkhole, Dibab Sinkhole) – Oman, approximately 30 m (98 ft) deep.[59][60]

- The Baatara gorge sinkhole and the Baatara gorge waterfall next to Tannourine in Lebanon

- Dashiwei Tiankeng in Guangxi, China, is 613 m (2,011 ft) deep, with vertical walls. At the bottom is an isolated patch of forest with rare species.[61]

- The Dragon Hole, located south of the Paracel Islands, is the deepest known underwater ocean sinkhole in the world. It is 300.89 m (987.2 ft) deep.[62][63]

- Shaanxi tiankeng cluster, in the Daba Mountains of southern Shaanxi, China, covers an area of nearly 5019 square kilometers[64] with the largest sinkhole being 520 meters in diameter and 320 meters deep.[65]

- Teiq Sinkhole (Taiq, Teeq, Tayq) in Oman is one of the largest sinkholes in the world by volume: 90,000,000 m3 (3.2×109 cu ft). Several perennial wadis fall with spectacular waterfalls into this 250 m (820 ft) deep sinkhole.[66]

- Xiaozhai Tiankeng – Chongqing, China. Double nested sinkhole with vertical walls, 662 m (2,172 ft) deep.[67]

- 2024 Kuala Lumpur sinkhole, Malaysia 8 meters deep with one victim missing.

Caribbean

[edit]- Dean's Blue Hole – Bahamas. The second deepest known sinkhole under the sea, depth 203 m (666 ft). Popular location for world championships of free diving, as well as recreational diving.

Central America

[edit]- Great Blue Hole – Belize. Spectacular, round sinkhole, 124 m (407 ft) deep. Unusual features are tilted stalactites in great depth, which mark the former orientation of limestone layers when this sinkhole was above sea level.

- 2007 Guatemala City sinkhole

- 2010 Guatemala City sinkhole

Europe

[edit]- Hranice Abyss, in the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, is the deepest known underwater cave in the world. The lowest confirmed depth (as of 27 September 2016) is 473 m (404 m below the water level).

- Maqluba, in Malta is a sinkhole with a surface area of around 4,765 square metres (51,290 sq ft) situated in the village of Qrendi in Malta. The diameter is around 50m, the depth is around 15m, and the perimeter 300m.

- Pozzo del Merro, near Rome, Italy. At the bottom of an 80 m (260 ft) conical pit, and approximately 400 m (1,300 ft) deep, it is among the deepest sinkholes in the world (see Sótano del Barro below).[citation needed]

- Red Lake – Croatia. Approximately 530 m (1,740 ft) deep pit with nearly vertical walls, contains an approximately 280–290 m (920–950 ft) deep lake.

- Gouffre de Padirac – France. It is 103 m (338 ft) deep, with a diameter of 33 metres (108 feet). Visitors descend 75 m via a lift or a staircase to a lake allowing a boat tour after entering into the cave system which contains a 55 km subterranean river.

- Vouliagmeni – Greece. The sinkhole of Vouliagmeni is known as "The Devil Well",[citation needed] because it is considered extremely dangerous. Four scuba divers have died in it.[68] Maximum depth of 35.2 m (115 ft 6 in) and horizontal penetration of 150 m (490 ft).

- Pouldergaderry – Ireland. This sinkhole is located in the townland of Kilderry South near Milltown, County Kerry at 52°7′57.5″N 9°44′45.4″W / 52.132639°N 9.745944°W.[69][citation needed] The sinkhole, which is located in an area of karst bedrock, is approximately 80 metres (260 ft) in diameter and 30 metres (98 ft) deep with many mature trees growing on the floor of the hole. At the level of the surrounding ground, the sinkhole covers an area of approximately 1.3 acres. Its presence is indicated on Ordnance Survey maps dating back to 1829.[70]

North America

[edit]Mexico

[edit]- Cave of Swallows – San Luis Potosí. 372 m (1,220 ft) deep, round sinkhole with overhanging walls.

- Puebla sinkhole – Santa Maria Zacatepec, Puebla. 120 m (400 ft) diameter and 15 m (50 ft) deep, it is still growing as of June 2021[update]. 2021.[71]

- Sima de las Cotorras – Chiapas. 160 m (520 ft) across, 140 m (460 ft) deep, with thousands of green parakeets and ancient rock paintings.

- Zacatón – Tamaulipas. Deepest water-filled sinkhole in world, 339 m (1,112 ft) deep. [further explanation needed]

United States

[edit]- Amberjack Hole – blue hole located 48 km (30 mi) off the coast of Sarasota, Florida.

- Bayou Corne sinkhole – Assumption Parish, Louisiana. About 25 acres in area[72] and 230 m (750 ft) deep.

- The Blue Hole – Santa Rosa, New Mexico. The surface entrance is only 80 feet (24 m) in diameter, it expands to a diameter of 130 feet (40 m) at the bottom.

- Daisetta Sinkholes – Daisetta, Texas. Several sinkholes have formed, the most recent in 2008 with a maximum diameter of 620 ft (190 m) and maximum depth of 45 m (150 ft).[73][74]

- Devil's Millhopper – Gainesville, Florida. 35 m (120 ft) deep, 500 ft (150 m) wide. Twelve springs, some more visible than others, feed a pond at the bottom.[75]

- Golly Hole or December Giant – Calera, Alabama. Appeared 2 December 1972. Approximately 300 by 325 ft (91 by 99 m) and 35 m (120 ft) deep.[76]

- Grassy Cove – Cumberland County, Tennessee. 13.6 km2 (5.3 sq mi) in area and 42.7 m (140 ft 1 in) deep,[77] a National Natural Landmark.

- Green Banana Hole – a blue hole located 80 km (50 mi) off the coast of Sarasota, Florida.

- Gypsum Sinkhole – Utah, in Capitol Reef National Park. Nearly 15 m (49 ft) in diameter and approximately 60 m (200 ft) deep.[78]

- Kingsley Lake – Clay County, Florida. 8.1 km2 (2,000 acres) in area, 27 m (89 ft) deep and almost perfectly round.

- Lake Peigneur – New Iberia, Louisiana. Original depth 3.4 m (11 ft), currently 400 m (1,300 ft) at Diamond Crystal Salt Mine collapse.[79]

- Winter Park Sinkhole – Winter Park, Florida. Appeared 8 May 1981. It was approximately 110 m (350 ft) wide and 25 m (75 ft) deep. It was notable as one of the largest recent sinkholes to form in the United States. It is now known as Lake Rose.[80]

Oceania

[edit]- Harwoods Hole – Abel Tasman National Park, New Zealand. 183 m (600 ft) deep.

South America

[edit]- Sima Humboldt – Bolívar, Venezuela. Largest sinkhole in sandstone, 314 m (1,030 ft) deep, with vertical walls. Unique, isolated forest on bottom.

- In the western part of Cerro Duida, Venezuela, there is a complex of canyons with sinkholes. Deepest sinkhole is 450 m (1,480 ft) deep (from lowest rim within canyon); total depth 950 m (3,120 ft).

See also

[edit]- List of sinkholes – Links to Wikipedia articles on sinkholes, blue holes, dolines, cenotes, and pit caves

- Akhayat sinkhole – Sinkhole in Mersin Province, Turkey

- Blyvooruitzicht – village in Gauteng, South Africa

- Caldera – Cauldron-like volcanic feature formed by the emptying of a magma chamber

- Cennet and Cehennem – Two sinkholes in Mersin Province; Turkey

- Dersios sinkhole – cave in Greece

- Dragon Hole – Deep underwater sinkhole in the South China Sea

- Estavelle – Karst ground orifice which is sometimes a sink and other times a source

- Forau de Aigualluts – River in France

- Gully – Landform created by running water and/or mass movement eroding sharply into soil

- Lake-burst

- Oak Island – Island in Nova Scotia, Canada

- Pingo – Mound of earth-covered ice

- Pipe Creek Sinkhole – paleontological site in Grant County, Indiana

- Turlough (lake) – Type of seasonal or periodic lake found in limestone areas of Ireland

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Williams, Paul (2004). "Dolines". In Gunn, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Caves and Karst Science. Taylor & Francis. pp. 628–642. ISBN 978-1-57958-399-6.

- ^ a b c Kohl, Martin (2001). "Subsidence and sinkholes in East Tennessee. A field guide to holes in the ground" (PDF). State of Tennessee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ Thomas, David; Goudie, Andrew, eds. (2009). The Dictionary of Physical Geography (3rd ed.). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 440. ISBN 978-1444313161.

- ^ a b Monroe, Watson Hiner (1970). "A glossary of Karst terminology". U.S. Geological Survey Water Supply Paper. 1899-K. doi:10.3133/wsp1899k.

- ^ "Caves and karst – dolines and sinkholes". British Geological Survey.

- ^ Breining, Greg (5 October 2007). "Getting Down and Dirty in an Underground River in Puerto Rico". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ Palmer, Arthur N. (1 January 1991). "Origin and morphology of limestone caves". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 103 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:1991GSAB..103....1P. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1991)103<0001:oamolc>2.3.co;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- ^ Friend, Sandra (2002). Sinkholes. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-56164-258-8. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Tills 2013, p. 181.

- ^ "Quarrying and the environment". bgs. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ "Sinkholes in Washington County". Utah gov Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011.

- ^ a b Tills 2013, p. 182.

- ^ Vincent, Jean-Baptiste; et al. (2 July 2015). "Large heterogeneities in comet 67P as revealed by active pits from sinkhole collapse" (PDF). Nature. 523 (7558): 63–66. Bibcode:2015Natur.523...63V. doi:10.1038/nature14564. PMID 26135448. S2CID 2993705.

- ^ Ritter, Malcolm (1 July 2015). "It's the pits: Comet appears to have sinkholes, study says". AP News. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Sinkholes". Water Science School. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Benson, Richard C.; Yuhr, Lynn B. (2015). Site Characterization in Karst and Pseudokarst Terraines: Practical Strategies and Technology for Practicing Engineers, Hydrologists and Geologists. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9924-9. ISBN 978-94-017-9923-2. S2CID 132318001.

- ^ a b c d e Newton, John G. (1987). "Development of sinkholes resulting from man's activities in the eastern United States" (PDF). Circular. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 968. U.S. Government Print Office. doi:10.3133/cir968. hdl:2027/uc1.31210020732440.

- ^ Kambesis, P.; Brucker, R.; Waltham, T.; Bell, F.; Culshaw, M. (2005). "Collapse sinkhole at Dishman Lane, Kentucky". Sinkholes and Subsidence: Karst and Cavernous Rocks in Engineering and Construction. Berlin: Springer. p. 281. doi:10.1007/b138363. ISBN 3-540-20725-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Sowers, George F. (1996). Building on sinkholes. New York: American Society of Civil Engineers. doi:10.1061/9780784401767. ISBN 0-7844-0176-4.

- ^ a b Waltham, Tony; Bell, Fred; Culshaw, Martin (2005). Sinkholes and subsidence: karst and cavernous rocks in engineering and construction (1st ed.). Berlin [u.a.]: Springer [u.a.] ISBN 978-3540207252.

- ^ Doctor, Katarina. "GIS and Spatial Statistical Methods for Determining Sinkhole Potential in Frederick Valley, Maryland, page 100 in Kuniansky, E.L., 2008, U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, Bowling Green, Kentucky, May 27–29, 2008: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5023, 142 p." (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Weary, David J. (2015). Doctor, Daniel; Land, Lewis; Stephenson, J (eds.). The cost of karst subsidence and sinkhole collapse in the United States compared with other natural hazards. University of South Florida. doi:10.5038/9780991000951. ISBN 978-0-9910009-5-1. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Kuniansky, E.L.; Weary, D.J.; Kaufmann, J.E. (2016). "The current status of mapping karst areas and availability of public sinkhole-risk resources in karst terrains of the United States" (PDF). Hydrogeology Journal. 24 (3). Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 614. Bibcode:2016HydJ...24..613K. doi:10.1007/s10040-015-1333-3. S2CID 130375566. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Possibly the nation's largest recent sinkhole – the 'December Giant' measuring 425 feet long, 350 feet wide and 150 feet deep – formed in central Alabama". USGS Denver Library Photographic Collection. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ Parise, M.; Gunn, J. (2007). "Natural and anthropogenic hazards in karst areas: an introduction". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 279 (1): 1–3. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.279....1P. doi:10.1144/SP279.1. S2CID 130950517.

- ^ Bonacci, O.; Ljubenkov, I.; Roje-Bonacci, T. (31 March 2006). "Karst flash floods: an example from the Dinaric karst (Croatia)". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 6 (2): 195–203. Bibcode:2006NHESS...6..195B. doi:10.5194/nhess-6-195-2006.

- ^ Tolmachev, Vladimir; Leonenko, Mikhail (2011). "Experience in Collapse Risk Assessment of Building on Covered Karst Landscapes in Russia". Karst Management. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1207-2_4. ISBN 978-94-007-1206-5.

- ^ "What is a sinkhole?". CNC3. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Largest and most impressive sinkholes of the world". Wondermondo. 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Naré sinkhole". Wondermondo. 5 August 2010.

- ^ Zhu, Xuewen; Chen, Weihai (2006). "Tiankengs in the karst of China" (PDF). Speleogenesis and Evolution of Karst Aquifers. 4: 1–18. ISSN 1814-294X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Sistema Zacatón". by Marcus Gary.

- ^ a b "Sistema Zacatón". Wondermondo. 3 July 2010.

- ^ Vazquez, Tyler (29 September 2017). "The Hole Truth". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1A, 2A. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ William L. Wilson; K. Michael Garman. "IDENTIFICATION AND DELINEATION OF SINKHOLE COLLAPSE HAZARDS IN FLORIDA USING GROUND PENETRATING RADAR AND ELECTRICAL RESISTIVITY IMAGING" (PDF). Subsurface Evaluations, Inc. Case 3 – Mariner Boulevard.

- ^ Paull, Charles K.; Dallimore, Scott R.; Jin, Young Keun; Caress, David W.; Lundsten, Eve; Gwiazda, Roberto; Anderson, Krystle; Hughes Clarke, John; Youngblut, Scott; Melling, Humfrey (22 March 2022). "Rapid seafloor changes associated with the degradation of Arctic submarine permafrost". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (12): e2119105119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11919105P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2119105119. PMC 8944826. PMID 35286188.

- ^ Katie Hunt (14 March 2022). "Holes the size of city blocks are forming in the Arctic seafloor". CNN. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Erchul, R.A. (1991). "Illegal disposal in sinkholes: The threat and the solution.". Appalachian Karst: Proceedings of the Appalachian Karst Symposium. 1991. National Speleological Society. ISBN 9780961509354.

- ^ Vesper, D.J.; Loop, C.M.; White, W.B. (2001). "Contaminant transport in karst aquifers" (PDF). Theoretical and Applied Karstology. 13 (14): 101–111. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ ""Haunted" Maya Underwater Cave Holds Human Bones". 16 January 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Rock, Tim (2007). Diving & Snorkeling Belize (4th ed.). Footscray, Vic.: Lonely Planet. p. 65. ISBN 9781740595315.

- ^ "Sinkholes". Wondermondo. 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Black Hole of Andros". Wondermondo. 17 August 2010.

- ^ a b "dolina". Hrvatska enciklopedija. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Subsidence". Waikato Regional Council. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "ponikva". Hrvatska enciklopedija. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Tills 2013, p. 184.

- ^ Fletcher, Dan (1 June 2010). "Massive Sinkhole Opens in Guatemala". Time. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Vidal, Luis; Jorge Nunez (2 June 2010). "¿Que diablos provoco este escalofriante hoyo?". Las Ultimas Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Than, Ker (1 June 2010). "Sinkhole in Guatemala: Giant Could Get Even Bigger". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ a b Waltham, T. (2008). "Sinkhole hazard case histories in karst terrains". Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. 41 (3): 291–300. Bibcode:2008QJEGH..41..291W. doi:10.1144/1470-9236/07-211. S2CID 128585380.

- ^ Halliday, W.R. (2007). "Pseudokarst in the 21st Century" (PDF). Journal of Cave and Karst Studies. 69 (1): 103–113. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Subsidence Incident | Gyproc".

- ^ a b Hussey, Sinéad (17 April 2020). "Crown hole appears in Magheracloone, Co Monaghan". RTÉ News.

- ^ a b "The cricket club that went down the hole". 16 October 2017.

- ^ Lóczy, Dénes, ed. (2015). "The Crater Lakes of Nagyhegyes". Landscapes and Landforms of Hungary – World Geomorphological Landscapes. Springer: 247. ISBN 978-3319089973.

- ^ Beaumont, P.B.; Vogel, J.C. (May–June 2006). "On a timescale for the past million years of human history in central South Africa". South African Journal of Science. 102: 217–228. hdl:10204/1944. ISSN 0038-2353.

- ^ Halls, Monty; Krestovnikoff, Miranda (2006). Scuba diving (1st American ed.). New York: DK Pub. p. 267. ISBN 9780756619497.

- ^ Rajendran, Sankaran; Nasir, Sobhi (2014). "ASTER mapping of limestone formations and study of caves, springs and depressions in parts of Sultanate of Oman". Environmental Earth Sciences. 71 (1): 133–146, figure 9d (page 142), page 144. Bibcode:2014EES....71..133R. doi:10.1007/s12665-013-2419-7. S2CID 128443371.

- ^ "Bimmah sinkhole". Wondermondo. 3 February 2013.

- ^ Zhu, Xuewen; et al. (2003). 广西乐业大石围天坑群发现探测定义与研究 [Dashiwei Tiankeng Group, Leye, Guangxi: discoveries, exploration, definition and research]. Nanning, Guangxi, China: Guangxi Scientific and Technical Publishers. ISBN 978-7-80666-393-6.

- ^ "China Exclusive: South China Sea "blue hole" declared world's deepest". New China. Xinhua. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016.

- ^ "Researchers just discovered the world's deepest underwater sinkhole in the South China Sea". The Washington Post.

- ^ "陕西发现天坑群地质遗迹并发现少见植物和飞猫" [Tiankeng group of geological relics with rare plants and flying cats found in Shaanxi]. Sohu.com Inc. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016.

- ^ "时事新闻--解密汉中天坑群——改写地质历史的世界级"自然博物馆"" [Deciphering the Hanzhong tiankeng group – world-class "Nature Museum"]. Hanzhong People's Municipal Government. 25 November 2016. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016.

- ^ "Dhofar caves: A tourist's paradise". Muscat Daily. 11 January 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016.

- ^ Zhu, Xuewen; Waltham, Tony (2006). "Tiankeng: definition and description" (PDF). Speleogenesis and Evolution of Karst Aquifers. 4 (1): 1–8, Fig. 4. Structural interpretation of Xiaozhai Tiankeng, page 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Schonauer, Scott (21 July 2007). "Missing American divers will be laid to rest after 30 years". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "52°07'57.5"N 9°44'45.4"W · Kilderry South, Co. Kerry, Ireland". 52°07'57.5"N 9°44'45.4"W · Kilderry South, Co. Kerry, Ireland.

- ^ "Shop.osi.ie Mapviewer". Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Guzman, Joseph (10 June 2021). "A sinkhole larger than a football field has appeared in Mexico — and it's still growing". TheHill. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Wines, Michael (25 September 2013). "Ground Gives Way, and a Louisiana Town Struggles to Find Its Footing". New York Times. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Horswell, Cindy (5 January 2009). "Daisetta sinkhole still a mystery 8 months after it formed". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (9 May 2008). "Sinkhole and Town: Now You See It". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ "Devils Millhopper Geological State Park". Floridastateparks.org. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ "Nation's largest sinkhole may be near Montevallo" (29 March 1973) The Tuscaloosa News

- ^ Dunigan, Tom. "Grassy Cove". Tennessee Landforms. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Cathedral Valley – Capitol Reef National Park". National Park Service, US Dept of Interior. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Mine Safety and Health Administration (13 August 1981). The Jefferson Island Mine inundation (Report). Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Huber, Red (13 November 2012). "Looking back at Winter Park's famous sinkhole". Orlando Sentinel.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

Bibliography

- Tills, Tony (2013), Science Year, World Book, Inc., ISBN 9780716605676

External links

[edit]- US Geological Survey Water Science School page about sinkholes

- Daily Telegraph slide show of 31 sinkholes

- Video of Sinkhole forming in Texas (8 May 2008)

- Google map of deepest "hole" for each state (Andy Martin)

- Tennessee sinkholes 54,000+ sinkholes

- James, Vincent (18 February 2014). "What are sinkholes, how do they form and why are we seeing so many?". The Independent. Retrieved 19 February 2014.