Doctor Who

| Doctor Who | |

|---|---|

Title card (2024–present) | |

| Genre | |

| Created by | |

| Showrunners |

|

| Written by | Various |

| Starring |

|

| Theme music composer | Ron Grainer |

| Opening theme | Doctor Who theme music |

| Composers |

|

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language | English |

| No. of seasons | 26 (1963–1989) |

| No. of series | 14 (2005–present) |

| No. of episodes |

|

| Production | |

| Executive producers |

|

| Camera setup |

|

| Running time | |

| Production companies | BBC Studios Productions Bad Wolf

|

| Original release | |

| Network | BBC1[c] |

| Release | 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 |

| Network | Fox / BBC1[d] |

| Release | 14 May 1996 / 27 May 1996 |

| Network | BBC One[e] |

| Release | 26 March 2005 – present |

| Network | Disney+[f] |

| Release | 25 November 2023 – present |

| Related | |

| Whoniverse | |

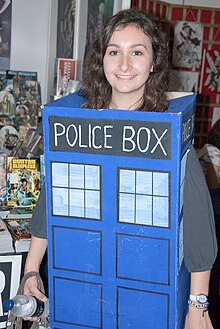

Doctor Who is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series, created by Sydney Newman, C. E. Webber and Donald Wilson, depicts the adventures of an extraterrestrial being called the Doctor, part of a humanoid species called Time Lords. The Doctor travels in the universe and in time using a time travelling spaceship called the TARDIS, which externally appears as a British police box. While travelling, the Doctor works to save lives and liberate oppressed peoples by combating foes. The Doctor often travels with companions.

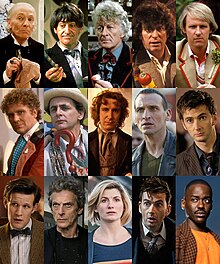

Beginning with William Hartnell, fourteen actors have headlined the series as the Doctor; as of 2024[update], Ncuti Gatwa leads the series as the Fifteenth Doctor. The transition from one actor to another is written into the plot of the series with the concept of regeneration into a new incarnation, a plot device in which, when a Time Lord is fatally injured, their cells regenerate and they are reincarnated, into a different body with mannerisms and behaviour, but the same memories, explaining each actor's distinct portrayal, as they all represent different stages in the life of the Doctor and, together, they form a single lifetime with a single narrative. The time-travelling nature of the plot means that different incarnations of the Doctor occasionally meet. The Doctor can also change ethnicity or gender; in 2017, Jodie Whittaker became the first woman cast in the lead role, and in 2024, Gatwa became the first black actor to headline the series.

The series is a significant part of popular culture in Britain[2] and elsewhere; it has gained a cult following. It has influenced generations of British television professionals, many of whom grew up watching the series.[3] Fans of the series are sometimes referred to as Whovians. The series has been listed in Guinness World Records as the longest-running science-fiction television series in the world,[4] as well as the "most successful" science-fiction series of all time, based on its overall broadcast ratings, DVD and book sales.[5]

The series originally ran from 1963 to 1989. There was an unsuccessful attempt to revive regular production in 1996 with a backdoor pilot in the form of a television film titled Doctor Who. The series was relaunched in 2005 and was produced in-house by BBC Wales in Cardiff. Since 2023, the show has been co-produced by Bad Wolf and BBC Studios Productions in Cardiff. Doctor Who has spawned numerous spin-offs as part of the Whoniverse, including comic books, films, novels and audio dramas, and the television series Torchwood (2006–2011), The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–2011), K9 (2009–2010), Class (2016), Tales of the TARDIS (2023–2024), and the upcoming The War Between the Land and the Sea. It has been the subject of many parodies and references in popular culture.

Premise

Doctor Who follows the adventures of the title character, a rogue Time Lord with somewhat unknown origins who goes by the name "the Doctor". The Doctor fled Gallifrey, the planet of the Time Lords, in a stolen TARDIS ("Time and Relative Dimension(s) in Space"), a time machine that travels by materialising into, and dematerialising out of, the time vortex. The TARDIS has a vast interior but appears smaller on the outside, and is equipped with a "chameleon circuit" intended to make the machine take on the appearance of local objects as a disguise. Because of a malfunction, the Doctor's TARDIS remains fixed as a blue British police box.[6]

Across time and space, the Doctor's many incarnations often find events that pique their curiosity, and try to prevent evil forces from harming innocent people or changing history, using only ingenuity and minimal resources, such as the versatile sonic screwdriver. The Doctor rarely travels alone and is often joined by one or more companions on these adventures; these companions are usually humans, owing to the Doctor's fascination with planet Earth, which also leads to frequent collaborations with the international military task force UNIT when Earth is threatened.[7] The Doctor is centuries old and, as a Time Lord, has the ability to regenerate when there is mortal damage to their body.[8] The Doctor's various incarnations have gained numerous recurring enemies during their travels, including the Daleks, their creator Davros, the Cybermen, and the renegade Time Lord the Master.[9]

History

Doctor Who was originally intended to appeal to a family audience[10] as an educational programme using time travel as a means to explore scientific ideas and famous moments in history. The programme first appeared on the BBC Television Service at 17:16:20 GMT on 23 November 1963; this was eighty seconds later than the scheduled programme time, because of announcements concerning the previous day's assassination of John F. Kennedy.[11][12] It was to be a regular weekly programme, each episode 25 minutes of transmission length. Discussions and plans for the programme had been in progress for a year. The head of drama Sydney Newman was mainly responsible for developing the programme, with the first format document for the series being written by Newman along with the head of the script department (later head of serials) Donald Wilson and staff writer C. E. Webber; in a 1971 interview Wilson claimed to have named the series, and when this claim was put to Newman he did not dispute it.[13] Writer Anthony Coburn, story editor David Whitaker and initial producer Verity Lambert also heavily contributed to the development of the series.[14][g]

On 31 July 1963, Whitaker commissioned Terry Nation to write a story under the title The Mutants. As originally written, the Daleks and Thals were the victims of an alien neutron bomb attack but Nation later dropped the aliens and made the Daleks the aggressors. When the script was presented to Wilson, it was immediately rejected as the programme was not permitted to contain any "bug-eyed monsters". According to Lambert, "We didn't have a lot of choice—we only had the Dalek serial to go ... We had a bit of a crisis of confidence because Donald [Wilson] was so adamant that we shouldn't make it. Had we had anything else ready we would have made that." Nation's script became the second Doctor Who serial – The Daleks (also known as The Mutants). The serial introduced the eponymous aliens that would become the series' most popular monsters, dubbed "Dalekmania", and was responsible for the BBC's first merchandising boom.[16]

We had to rely on the story because there was little we could do with the effects. Star Wars in a way was the turning point. Once Star Wars had happened, Doctor Who effectively was out of date from that moment on really, judged by that level of technological expertise.

The BBC drama department produced the programme for 26 seasons, broadcast on BBC One. Due to his increasingly poor health, William Hartnell, first actor to play the Doctor, was succeeded by Patrick Troughton in 1966. In 1970, Jon Pertwee replaced Troughton and the series began production in colour. In 1974, Tom Baker was cast as the Doctor. His eccentric personality became hugely popular, with viewing figures for the series returning to a level not seen since the height of "Dalekmania" a decade earlier.[18] After seven years in the role, Baker was replaced by Peter Davison in 1981, and Colin Baker replaced Davison in 1984. In 1985, the channel's controller Michael Grade cancelled the upcoming twenty-third season, forcing the series into an eighteen-month hiatus.[19][20][21] In 1986, the series was recommissioned on the condition that Baker left the role of the Doctor,[21] which was recast to Sylvester McCoy in 1987. Falling viewing numbers, a decline in the public perception of the series and a less-prominent transmission slot saw production ended in 1989 by Peter Cregeen, the BBC's new head of series.[22] Although it was effectively cancelled, the BBC repeatedly affirmed over several years that the series would return.[23]

While in-house production concluded, the BBC explored an independent production company to relaunch the series. Philip Segal, a British expatriate who worked for Columbia Pictures' television arm in the United States, had approached the BBC as early as July 1989, while the 26th season was still in production.[23] Segal's negotiations eventually led to a Doctor Who television film as a pilot for an American series, broadcast on the Fox Network in 1996, as an international co-production between Fox, Universal Pictures, the BBC and BBC Worldwide. Starring Paul McGann as the Doctor, the film was successful in the UK (with 9.1 million viewers), but was less so in the United States and did not lead to a series.[23]

Licensed media such as novels and audio plays provided new stories, but as a television programme, Doctor Who remained dormant. In September 2003,[24][25] BBC Television announced the in-house production of a new series, after several years of attempts by BBC Worldwide to find backing for a feature film version. The 2005 revival of Doctor Who is a direct plot continuation of the original 1963–1989 series and the 1996 television film. The executive producers of the new incarnation of the series were Queer as Folk writer Russell T Davies and BBC Cymru Wales head of drama Julie Gardner. From 2005, the series switched from a multi-camera to a single-camera setup.[26]

Starring Christopher Eccleston as the Doctor, Doctor Who returned with the episode "Rose" on BBC One on 26 March 2005, after a 16-year hiatus of in-house production.[27] Eccleston left after one series and was replaced by David Tennant.[28] Davies left the production team in 2009.[29] Steven Moffat, a writer under Davies, was announced as his successor, along with Matt Smith as the new Doctor.[30] Smith decided to leave the role of the Doctor in 2013, the 50th anniversary year.[31] He was replaced by Peter Capaldi.[32]

In January 2016, Moffat announced that he would step down after the 2017 finale, to be replaced by Chris Chibnall in 2018.[33] Jodie Whittaker, the first female Doctor, appeared in three series, the last of which was shortened due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[34]

Both Whittaker and Chibnall announced that they would depart the series after a series of specials in 2022.[35] Davies returned as showrunner from the 60th anniversary specials, twelve years after he had left the series previously.[36] Bad Wolf co-produces the series in partnership with BBC Studios Productions.[37] Bad Wolf's involvement sees Gardner return to the series alongside Davies and Jane Tranter, who recommissioned the series in 2005.[36]

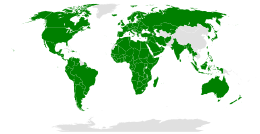

The programme has been sold to many other countries worldwide ().

Public consciousness

It has been claimed that the transmission of the first episode was delayed by ten minutes due to extended news coverage of the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy the previous day; in fact, it went out after a delay of eighty seconds.[38] The BBC believed that coverage of the assassination, as well as a series of power blackouts across the country, had caused many viewers to miss this introduction to a new series, and it was broadcast again on 30 November 1963, just before episode two.[39][40]

The programme soon became a national institution in the United Kingdom, with a large following among the general viewing audience.[42][43] The show received controversy over the suitability of the series for children. Morality campaigner Mary Whitehouse repeatedly complained to the BBC over what she saw as the programme's violent, frightening and gory content. According to Radio Times, the series "never had a more implacable foe than Mary Whitehouse".[44]

A BBC audience research survey conducted in 1972 found that, by their own definition of violence ("any act[s] which may cause physical and/or psychological injury, hurt or death to persons, animals or property, whether intentional or accidental"), Doctor Who was the most violent of the drama programmes the corporation produced at the time.[45] The same report found that 3% of the surveyed audience believed the series was "very unsuitable" for family viewing.[46] Responding to the findings of the survey in The Times newspaper, journalist Philip Howard maintained that, "to compare the violence of Dr Who, sired by a horse-laugh out of a nightmare, with the more realistic violence of other television series, where actors who look like human beings bleed paint that looks like blood, is like comparing Monopoly with the property market in London: both are fantasies, but one is meant to be taken seriously."[45]

During Jon Pertwee's second season as the Doctor, in the serial Terror of the Autons (1971), images of murderous plastic dolls, daffodils killing unsuspecting victims, and blank-featured policemen marked the apex of the series' ability to frighten children.[47] Other notable moments in that decade include a disembodied brain falling to the floor in The Brain of Morbius[48] and the Doctor apparently being drowned by a villain in The Deadly Assassin (both 1976).[49] Mary Whitehouse's complaint about the latter incident prompted a change in BBC policy towards the series, with much tighter controls imposed on the production team,[50] and the series' next producer, Graham Williams, was under a directive to take out "anything graphic in the depiction of violence".[51] John Nathan-Turner produced the series during the 1980s and said in the documentary More Than Thirty Years in the TARDIS that he looked forward to Whitehouse's comments because the ratings of the series would increase soon after she had made them. Nathan-Turner also got into trouble with BBC executives over the violence he allowed to be depicted for season 22 of the series in 1985, which was publicly criticised by controller Michael Grade and given as one of his reasons for suspending the series for 18 months.[52]

The phrase "hiding behind the sofa" (or "watching from behind the sofa") entered British pop culture, signifying the stereotypical but apocryphal early-series behaviour of children who wanted to avoid seeing frightening parts of a television programme while remaining in the room to watch the remainder of it.[53][54] The Economist presented "hiding behind the sofa whenever the Daleks appear" as a British cultural institution on a par with Bovril and tea-time.[55] Paul Parsons, author of The Science of Doctor Who, explains the appeal of hiding behind the sofa as the activation of the fear response in the amygdala in conjunction with reassurances of safety from the brain's frontal lobe.[56] The phrase retains this association with Doctor Who, to the point that in 1991 the Museum of the Moving Image in London named its exhibition celebrating the programme Behind the Sofa. The electronic theme music too was perceived as eerie, novel, and frightening at the time. A 2012 article placed this childhood juxtaposition of fear and thrill "at the center of many people's relationship with the series",[57] and a 2011 online vote at Digital Spy deemed the series the "scariest TV show of all time".[58]

The image of the TARDIS has become firmly linked to the series in the public's consciousness; BBC scriptwriter Anthony Coburn, who lived in the resort of Herne Bay, Kent, was one of the people who conceived the idea of a police box as a time machine.[59] In 1996, the BBC applied for a trademark to use the TARDIS' blue police box design in merchandising associated with Doctor Who.[60] In 1998, the Metropolitan Police Authority filed an objection to the trademark claim; but in 2002, the Patent Office ruled in favour of the BBC.[61][62][63]

The 21st-century revival of the programme became the centrepiece of BBC One's Saturday schedule and "defined the channel".[64] Many renowned actors have made guest-starring appearances in various stories including Kylie Minogue,[65] Sir Ian McKellen,[66] and Andrew Garfield[67] among others.[68] According to an article in the Daily Telegraph in 2009, the revival of Doctor Who had consistently received high ratings, both in number of viewers and as measured by the Appreciation Index.[69] In 2007, Caitlin Moran, television reviewer for The Times, wrote that Doctor Who is "quintessential to being British".[70] According to Steven Moffat, the American film director Steven Spielberg has commented that "the world would be a poorer place without Doctor Who".[71]

On 4 August 2013, a live programme titled Doctor Who Live: The Next Doctor[72] was broadcast on BBC One, during which the actor who was going to play the Twelfth Doctor was revealed.[73] The live show was watched by an average of 6.27 million in the UK, and was also simulcast in the United States, Canada and Australia.[74][75]

Episodes

Doctor Who originally ran for 26 seasons on BBC One, from 23 November 1963 until 6 December 1989. During the original run, each weekly episode formed part of a story (or "serial")—usually of four to six parts in earlier years and three to four in later years.[citation needed] Some notable exceptions were: The Daleks' Master Plan, which aired twelve episodes (plus an earlier one-episode teaser,[76] "Mission to the Unknown", featuring none of the regular cast[77]); almost an entire season of seven-episode serials (season 7); the ten-episode serial The War Games;[78] and The Trial of a Time Lord, which ran for fourteen episodes (albeit divided into three production codes and four narrative segments) during season 23.[79] Occasionally, serials were loosely connected by a story line, such as season 8 focusing on the Doctor battling a rogue Time Lord called the Master,[80][81] season 16's quest for the Key to Time,[82] season 18's journey through E-Space and the theme of entropy,[83] and season 20's Black Guardian trilogy.[84]

The programme was intended to be educational and for family viewing on the early Saturday evening schedule.[85] It initially alternated stories set in the past, which taught younger audience members about history, and with those in the future or outer space, focusing on science.[85] This was also reflected in the Doctor's original companions, one of whom was a science teacher and another a history teacher.[85]

However, science fiction stories came to dominate the programme, and the history-oriented episodes, which were not popular with the production team,[85] were dropped after The Highlanders (1967). While the show continued to use historical settings, they were generally used as a backdrop for science fiction tales,[86][87] with one exception: Black Orchid (1982), set in 1920s England.[88]

The early stories were serialised in nature, with the narrative of one story flowing into the next and each episode having its own title, although produced as distinct stories with their own production codes.[89] Following The Gunfighters (1966), however, each serial was given its own title, and the individual parts were assigned episode numbers.[89]

Of the programme's many writers, Robert Holmes was the most prolific,[90] while Douglas Adams became the best known outside Doctor Who itself, due to the popularity of his Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy works.[91][92]

The serial format changed for the 2005 revival, with what was now called a series usually consisting of thirteen 45-minute, self-contained episodes (60 minutes with adverts, on overseas commercial channels) and an extended 60-minute episode broadcast on Christmas Day. This system was shortened to twelve episodes and one Christmas special following the revival's eighth series, and ten episodes from the eleventh series. Each series includes standalone and multiple episodic stories, often linked with a loose story arc resolved in the series finale. As in the early "classic" era, each episode has its own title, whether stand-alone or part of a larger story. Occasionally, regular-series episodes will exceed the 45-minute run time; notably, the episodes "Journey's End" from 2008 and "The Eleventh Hour" from 2010 were longer than an hour.[citation needed]

884 Doctor Who instalments have been televised since 1963, ranging between 25-minute episodes (the most common format for the classic era), 45/50-minute episodes (for Resurrection of the Daleks in the 1984 series, a single season in 1985, and the most common format for the revival era since 2005), two feature-length productions (1983's "The Five Doctors" and the 1996 television film), twelve Christmas specials (most of approximately 60 minutes' duration, one of 72 minutes), and four additional specials ranging from 60 to 75 minutes in 2009, 2010, and 2013. Four mini-episodes, running about eight minutes each, were also produced for the 1993, 2005, and 2007 Children in Need charity appeals, while another mini-episode was produced in 2008 for a Doctor Who–themed edition of The Proms. The 1993 two-part story, entitled Dimensions in Time, was made in collaboration with the cast of the BBC soap-opera EastEnders and was filmed partly on the EastEnders set. A two-part mini-episode was also produced for the 2011 edition of Comic Relief.[citation needed] Starting with the 2009 special "Planet of the Dead", the series was filmed in 1080i for HDTV[93] and broadcast simultaneously on BBC One and BBC HD.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the show, a special 3D episode, "The Day of the Doctor", was broadcast in 2013.[94] In March 2013, it was announced that Tennant and Piper would be returning[95] and that the episode would have a limited cinematic release worldwide.[96]

In June 2017, it was announced that due to the terms of a deal between BBC Worldwide and SMG Pictures in China, the company has first right of refusal on the purchase for the Chinese market of future series of the programme until and including Series 15.[97][98]

Missing episodes

Between 1967 and 1978, large amounts of older material stored in the BBC's various video tape and film libraries was either destroyed[h] or wiped. This included many early episodes of Doctor Who, those stories featuring the first two Doctors: William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton. In all, 97 of 253 episodes produced during the programme's first six years are not held in the BBC's archives (most notably seasons 3, 4, and 5, from which 79 episodes are missing).[99][100] In 1972, almost all episodes then made were known to exist at the BBC,[101] while by 1978 the practice of wiping tapes and destroying "spare" film copies had been brought to a stop.[102]

No 1960s episodes exist on their original videotapes (all surviving prints being film transfers), though some were transferred to film for editing before transmission and exist in their broadcast form.[103]

Some episodes have been returned to the BBC from the archives of other countries that bought prints for broadcast or by private individuals who acquired them by various means. Early colour videotape recordings made off-air by fans have also been retrieved, as well as excerpts filmed from the television screen onto 8 mm cine film and clips that were shown on other programmes. Audio versions of all lost episodes exist from home viewers who made tape recordings of the show. Short clips from every story with the exception of Marco Polo (1964), "Mission to the Unknown" (1965) and The Massacre (1966) also exist.

In addition to these, there are off-screen photographs made by photographer John Cura, who was hired by various production personnel to document many of their programmes during the 1950s and 1960s, including Doctor Who.[citation needed] These have been used in fan reconstructions of the serials. The BBC has tolerated these amateur reconstructions, provided they are not sold for profit and are distributed as low-quality copies.[104]

One of the most sought-after lost episodes is part four of the last William Hartnell serial, The Tenth Planet (1966), which ends with the First Doctor transforming into the Second.[105] The only portion of this in existence, barring a few poor-quality silent 8 mm clips, is the few seconds of the regeneration scene, as it was shown on the children's magazine show Blue Peter. With the approval of the BBC, efforts are now underway to restore as many of the episodes as possible from the extant material.[citation needed]

"Official" reconstructions have also been released by the BBC on VHS, on MP3 CD-ROM, and as special features on DVD. The BBC, in conjunction with animation studio Cosgrove Hall, reconstructed the missing episodes 1 and 4 of The Invasion (1968), using remastered audio tracks and the comprehensive stage notes for the original filming, for the serial's DVD release in November 2006.[citation needed] The missing episodes of The Reign of Terror were animated by animation company Theta-Sigma, in collaboration with Big Finish, and became available for purchase in May 2013 through Amazon.com.[106] Subsequent animations made in 2013 include The Tenth Planet, The Ice Warriors (1967) and The Moonbase (1967).[107]

In April 2006, Blue Peter launched a challenge to find missing Doctor Who episodes with the promise of a full-scale Dalek model as a reward.[108] In December 2011, it was announced that part 3 of Galaxy 4 (1965) and part 2 of The Underwater Menace (1967) had been returned to the BBC by a fan who had purchased them in the mid-1980s without realising that the BBC did not hold copies of them.[109]

On 10 October 2013, the BBC announced that films of eleven episodes, including nine missing episodes, had been found in a Nigerian television relay station in Jos.[110] Six of the eleven films discovered were the six-part serial The Enemy of the World (1968), from which all but the third episode had been missing.[111] The remaining films were from another six-part serial, The Web of Fear (1968), and included the previously missing episodes 2, 4, 5 and 6. Episode 3 of The Web of Fear is still missing.[112]

Characters

The Doctor

The Doctor was initially shrouded in mystery. In the programme's early days, the character was an eccentric alien traveller of great intelligence who battled injustice while exploring time and space in an unreliable time machine, the "TARDIS" (an acronym for Time and Relative Dimension in Space), which notably appears much larger on the inside than on the outside.[i][113]

The initially irascible and slightly sinister Doctor quickly mellowed into a more compassionate figure and was eventually revealed to be a Time Lord, whose race are from the planet Gallifrey, which the Doctor fled by stealing the TARDIS.[114][115]

Changes of appearance

Producers introduced the concept of regeneration to permit the recasting of the main character. This was prompted by the poor health of the original star, William Hartnell.[116][117] The term "regeneration" was not conceived until the Doctor's third on-screen regeneration; Hartnell's Doctor merely described undergoing a "renewal", and the Second Doctor underwent a "change of appearance".[118][119] The device has allowed for the recasting of the actor various times in the show's history, as well as the depiction of alternative Doctors either from the Doctor's relative past or future.[120]

The serials The Deadly Assassin (1976) and Mawdryn Undead (1983) established that a Time Lord can only regenerate 12 times, for a total of 13 incarnations.[121][122] This line became stuck in the public consciousness despite not often being repeated and was recognised by producers of the show as a plot obstacle for when the show finally had to regenerate the Doctor a thirteenth time.[121][123] The episode "The Time of the Doctor" (2013) depicted the Doctor acquiring a new cycle of regenerations, starting from the Twelfth Doctor, due to the Eleventh Doctor being the product of the Doctor's twelfth regeneration from his original set.[124]

Although the idea of casting a woman as the Doctor had been suggested by the show's writers several times, including by Newman in 1986 and Davies in 2008, until 2017, all official depictions were played by men.[125][126] Jodie Whittaker took over the role as the Thirteenth Doctor at the end of the 2017 Christmas special and is the first woman to be cast as the character.[127] The show introduced the Time Lords' ability to change sex on regeneration in earlier episodes, first in dialogue, then with Michelle Gomez's version of the Master[128][129] and T'Nia Miller's version of the General.[130]

Upon Whittaker's final appearance as the character in "The Power of the Doctor" on 23 October 2022, she regenerated into a form portrayed by David Tennant, who was confirmed to be the Fourteenth Doctor and the first actor to play two incarnations, having previously played the Tenth Doctor. In the same year, Ncuti Gatwa was revealed to be portraying the Fifteenth Doctor, making him the first black actor to headline the series.[131][132]

| Series lead | Incarnation | Tenure[j] |

|---|---|---|

| William Hartnell | First Doctor | 1963–1966 |

| Patrick Troughton | Second Doctor | 1966–1969 |

| Jon Pertwee | Third Doctor | 1970–1974 |

| Tom Baker | Fourth Doctor | 1974–1981 |

| Peter Davison | Fifth Doctor | 1982–1984 |

| Colin Baker | Sixth Doctor | 1984–1986 |

| Sylvester McCoy | Seventh Doctor | 1987–1989 |

| Paul McGann | Eighth Doctor | 1996 |

| Christopher Eccleston | Ninth Doctor | 2005 |

| David Tennant | Tenth Doctor | 2005–2010 |

| Matt Smith | Eleventh Doctor | 2010–2013 |

| Peter Capaldi | Twelfth Doctor | 2014–2017 |

| Jodie Whittaker | Thirteenth Doctor | 2018–2022 |

| David Tennant | Fourteenth Doctor | 2023 |

| Ncuti Gatwa | Fifteenth Doctor | 2023–present |

In addition to those actors who have headlined the series, others have portrayed versions of the Doctor in guest roles. Notably, in 2013, John Hurt guest-starred as a hitherto unknown incarnation of the Doctor known as the War Doctor in the run-up to the show's 50th-anniversary special "The Day of the Doctor".[133] He is shown in mini-episode "The Night of the Doctor" retroactively inserted into the show's fictional chronology between McGann's and Eccleston's Doctors, although his introduction was written so as not to disturb the established numerical naming of the Doctors.[134] The show later introduced another such unknown past Doctor with Jo Martin's recurring portrayal of the Fugitive Doctor, beginning with "Fugitive of the Judoon" (2020).[135] An example from the classic series comes from The Trial of a Time Lord (1986), in which Michael Jayston's character the Valeyard is described as an amalgamation of the darker sides of the Doctor's nature, somewhere between the twelfth and final incarnation.[136] The most recent example is when Richard E. Grant, who previously portrayed an alternate version of the Doctor known as the Shalka Doctor in the animated series Scream of the Shalka (2003), appeared as a hologram of a past Doctor in "Rogue" (2024).[137]

On rare occasions, other actors have stood in for the lead. In "The Five Doctors", Richard Hurndall played the First Doctor due to William Hartnell's death in 1975;[138] 34 years later David Bradley similarly replaced Hartnell in "Twice Upon a Time".[139] In Time and the Rani, Sylvester McCoy briefly played the Sixth Doctor during the regeneration sequence, carrying on as the Seventh.[140] In other media, the Doctor has been played by various other actors, including Peter Cushing in two films.[141]

The casting of a new Doctor has often inspired debate and speculation. Common topics of focus include the Doctor's sex (prior to the casting of Whittaker, all official incarnations were male), race (all Doctors were white prior to the casting of Jo Martin in "Fugitive of the Judoon") and age (the youngest actor to be cast is Smith at 26, and the oldest are Capaldi and Hartnell, both 55).[142][143][144]

Meetings of different incarnations

There have been instances of actors returning later to reprise their specific Doctor's role. In 1973's The Three Doctors, William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton returned alongside Jon Pertwee. For 1983's "The Five Doctors", Troughton and Pertwee returned to star with Peter Davison, and Tom Baker appeared in previously unseen footage from the uncompleted Shada serial. For this episode, Richard Hurndall replaced William Hartnell. Patrick Troughton again returned in 1985's The Two Doctors with Colin Baker.[138]

In 2007, Peter Davison returned in the Children in Need short "Time Crash" alongside David Tennant.[145] In "The Name of the Doctor" (2013), the Eleventh Doctor meets a previously unseen incarnation of himself, subsequently revealed to be the War Doctor.[133] In the following episode, "The Day of the Doctor", David Tennant's Tenth Doctor appeared alongside Matt Smith as the Eleventh Doctor and John Hurt as the War Doctor, as well as brief footage of all the previous actors.[146] In 2017, the First Doctor (this time portrayed by David Bradley) returned alongside Peter Capaldi in "The Doctor Falls" and "Twice Upon a Time".[139]

In 2020's "Fugitive of the Judoon", Jodie Whittaker as the Thirteenth Doctor meets Jo Martin's incarnation of the Doctor, subsequently known as the Fugitive Doctor; they interact again in the episode "The Timeless Children" later that year as well as in "Once, Upon Time" in 2021. In her final episode, "The Power of the Doctor" (2022), Whittaker interacts with the Guardians of the Edge, manifestations of the Doctor's First (Bradley), Fifth (Davison), Sixth (Colin Baker), Seventh (McCoy), and Eighth (McGann) incarnations.[147] Additionally, multiple incarnations of the Doctor have met in various audio dramas and novels based on the television show.[148]

Companions

The companion figure – generally a human – has been a constant feature in Doctor Who since the programme's inception in 1963. One of the roles of the companion is to be a reminder for the Doctor's "moral duty".[149] The Doctor's first companions seen on-screen were his granddaughter Susan Foreman (Carole Ann Ford) and her teachers Barbara Wright (Jacqueline Hill) and Ian Chesterton (William Russell). These characters were intended to act as audience surrogates, through which the audience would discover information about the Doctor, who was to act as a mysterious father figure.[149] The only story from the original series in which the Doctor travels alone is "The Deadly Assassin" (1976).[150] Notable companions from the earlier series include Romana (Mary Tamm and Lalla Ward), a Time Lady; Sarah Jane Smith (Elisabeth Sladen); and Jo Grant (Katy Manning).[151][152] Dramatically, these characters provide a figure with whom the audience can identify and serve to further the story by requesting exposition from the Doctor and manufacturing peril for the Doctor to resolve. The Doctor regularly gains new companions and loses old ones;[153] sometimes they return home or find new causes—or loves—on worlds they have visited. Some have died during the course of the series.[154] Companions are usually humans or humanoid aliens.[153]

Since the 2005 revival, the Doctor generally travels with a primary female companion, who occupies a larger narrative role. Steven Moffat described the companion as the main character of the show, as the story begins anew with each companion and she undergoes more change than the Doctor.[155][156] The primary companions of the Ninth and Tenth Doctors were Rose Tyler (Billie Piper), Martha Jones (Freema Agyeman), and Donna Noble (Catherine Tate), with Mickey Smith (Noel Clarke) and Jack Harkness (John Barrowman) recurring as secondary companion figures.[157][158] The Eleventh Doctor became the first to travel with a married couple, Amy Pond (Karen Gillan) and Rory Williams (Arthur Darvill), whilst out-of-sync meetings with River Song (Alex Kingston)[159] and Clara Oswald (Jenna Coleman)[156] provided ongoing story arcs that continued with the Twelfth Doctor.[160] The tenth series included the alien Nardole (Matt Lucas)[161] and introduced Pearl Mackie as Bill Potts,[162] the Doctor's first openly gay companion. Pearl Mackie said that the increased representation of LGBTQ people is important on a mainstream show.[163] The Thirteenth Doctor has primarily travelled with Ryan Sinclair (Tosin Cole), Graham O'Brien (Bradley Walsh), Yasmin Khan (Mandip Gill),[164] and Dan Lewis (John Bishop).[165]

Some companions have gone on to reappear, either in the main series or in spin-offs. Sarah Jane Smith became the central character in The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–2011) following a return to Doctor Who in 2006. Guest stars in the series include former companions Jo Grant, K9, and Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart (Nicholas Courtney).[166] The character of Jack Harkness also served to launch a spin-off, Torchwood (2006–2011), in which Martha Jones also appeared.[167]

Foes

When Sydney Newman commissioned the series, he specifically did not want to perpetuate the cliché of the "bug-eyed monster" of science fiction.[168] However, monsters were popular with audiences and so became a staple of Doctor Who almost from the beginning.[169] Daleks, Cybermen, and the Master are some of the most iconic foes the Doctor has battled in the series.[9]

With the show's 2005 revival, executive producer Russell T Davies stated his intention to reintroduce the classic monsters of Doctor Who.[170] The Autons with the Nestene Consciousness, first seen in 1970's Spearhead from Space, and Daleks, first seen in 1963's The Daleks, returned in series 1. Davies's successor, Steven Moffat, continued the trend by reviving the Silurians, also first seen in 1970, in series 5 and Zygons, first seen in 1975, in the 50th-anniversary special.[171] Since its 2005 return, the series has also introduced new recurring aliens: Slitheen (Raxacoricofallapatorians), Ood, Judoon, Weeping Angels and the Silence.[9][172]

Daleks

The Daleks, which first appeared in the show's second serial in 1963,[173][174] are Doctor Who's oldest villains. The Daleks are Kaleds from the planet Skaro, mutated by the scientist Davros and housed in mechanical armour shells for mobility. The actual creatures resemble octopuses with large, pronounced brains. Their armour shells have a single eye-stalk, a sink-plunger-like device that serves the purpose of a hand, and a directed-energy weapon. Their main weakness is their eyestalk; attacks upon them using various weapons can blind a Dalek, making it go mad. Their chief role in the series plot, as they frequently remark in their instantly recognisable metallic voices, is to "exterminate" all non-Dalek beings. They even attack the Time Lords in the Time War, as shown during the 50th Anniversary of the show. They continue to be a recurring 'monster' within the Doctor Who franchise, having appeared in every series since 2005.[175] Davros has also been a recurring figure since his debut in Genesis of the Daleks, although played by several different actors.[176]

The Daleks were created by the writer Terry Nation (who intended them to be an allegory of the Nazis)[177] and BBC designer Raymond Cusick.[178] The Daleks' début in the programme's second serial, The Daleks (1963–1964), made both the Daleks and Doctor Who very popular. A Dalek appeared on a postage stamp celebrating British popular culture in 1999, photographed by Lord Snowdon.[179] The Daleks received another stamp in 2013 as part of the 50th anniversary.[180] In "Victory of the Daleks" a new set of Daleks were introduced that come in a range of colours; the colour denoting its role within the species.[181]

Cybermen

Cybermen were originally a wholly organic species of humanoids originating on Earth's twin planet Mondas that began to implant more and more artificial parts into their bodies. This led to the race becoming coldly logical and calculating cyborgs, with emotions usually only shown when naked aggression was called for. With the demise of Mondas, they acquired Telos as their new home planet. They continue to be a recurring 'monster' within the Doctor Who franchise.[182][183]

The Cybermen have evolved dramatically over the course of the show. They were reintroduced in the 2006 series in the form of alternate universe aliens, with radically different back stories.[184] The standard Cybermen returned in "Closing Time", though they kept their 2006 design.[185] In the 2020 series, the Cybermen aligned themselves with The Master, and were given the ability to regenerate.[186]

The Master

The Master is the Doctor's archenemy, a renegade Time Lord who desires to rule the universe. Conceived as "Professor Moriarty to the Doctor's Sherlock Holmes",[187] the character first appeared in 1971. As with the Doctor, the role has been portrayed by several actors, since the Master is a Time Lord as well and able to regenerate; the first of these actors was Roger Delgado, who continued in the role until his death in 1973. The Master was briefly played by Peter Pratt and Geoffrey Beevers until Anthony Ainley took over and continued to play the character until Doctor Who's hiatus in 1989.[188] The Master returned in the 1996 television movie of Doctor Who, and was played by American actor Eric Roberts.[189]

Following the series revival in 2005, Derek Jacobi provided the character's reintroduction in the 2007 episode "Utopia". During that story, the role was then assumed by John Simm, who returned to the role multiple times throughout the Tenth Doctor's tenure.[190] In the 2014 episode "Dark Water", it was revealed that the Master had become a female incarnation or "Time Lady", going by the name of "Missy" (short for Mistress, the feminine equivalent of "Master"). This incarnation is played by Michelle Gomez. Simm returned to his role as the Master alongside Gomez in the tenth series.[191] The Master returned for the 2020 twelfth series with Sacha Dhawan in the role.[192] This incarnation dubbed himself the "Spy Master" referencing a role he had taken with MI6.[193]

Music

Theme music

The Doctor Who theme music was one of the first electronic music signature tunes for television, and after more than a half century remains one of the most easily recognised. The original theme was composed by Ron Grainer and realised by Delia Derbyshire of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, with assistance from Dick Mills, and was released as a single on Decca F 11837 in 1964. The Derbyshire arrangement served, with minor edits, as the theme tune up to the end of season 17 (1979–1980). It is regarded as a significant and innovative piece of electronic music recorded well before the availability of commercial synthesisers or multitrack mixers. Each note was individually created by cutting, splicing, speeding up and slowing down segments of analogue tape containing recordings of a single plucked string, white noise, and the simple harmonic waveforms of test-tone oscillators, intended for calibrating equipment and rooms, not creating music. New techniques were invented to allow mixing of the music, as this was before the era of multitrack tape machines. On hearing the finished result, Grainer asked, "Jeez, Delia, did I write that?" She answered, "Most of it."[194] Although Grainer was willing to give Derbyshire the co-composer credit, it was against BBC policy at the time. She would not receive an on-screen credit until the 50th-anniversary story "The Day of the Doctor" in 2013.[195][196]

A different arrangement was recorded by Peter Howell for season 18 (1980), which was in turn replaced by Dominic Glynn's arrangement for the season-long serial The Trial of a Time Lord in season 23 (1986). Keff McCulloch provided the new arrangement for the Seventh Doctor's era, which lasted from season 24 (1987) until the series' suspension in 1989. American composer John Debney created a new arrangement of Grainer's original theme for Doctor Who in 1996. For the return of the series in 2005, Murray Gold provided a new arrangement, which featured samples from the 1963 original with further elements added in the 2005 Christmas episode "The Christmas Invasion".[197][198]

A new arrangement of the theme, once again by Gold, was introduced in the 2007 Christmas special episode, "Voyage of the Damned".[199] Gold returned as composer for the 2010 series, and was responsible for a new version of the theme which was reported to have had a hostile reception from some viewers.[200] In 2011, the theme tune charted at number 228 of radio station Classic FM's Hall of Fame, a survey of classical music tastes. A revised version of Gold's 2010 arrangement had its debut over the opening titles of the 2012 Christmas special "The Snowmen", and a further revision of the arrangement was made for the 50th-anniversary special "The Day of the Doctor" in November 2013.[201]

Versions of the "Doctor Who Theme" have also been released as pop music. In the early 1970s, Jon Pertwee, who had played the Third Doctor, recorded a version of the Doctor Who theme with spoken lyrics, titled, "Who Is the Doctor".[k] In 1978, a disco version of the theme in the UK, Denmark and Australia by the group Mankind, which reached number 24 in the UK charts. In 1988, the band The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (later known as The KLF) released the single "Doctorin' the Tardis" under the name The Timelords, which reached No. 1 in the UK and No. 2 in Australia; this version incorporated several other songs, including "Rock and Roll Part 2" by Gary Glitter (who recorded vocals for some of the CD-single remix versions of "Doctorin' the Tardis").[202] Others who have covered or reinterpreted the theme include Orbital,[202] Pink Floyd,[202] the Australian string ensemble Fourplay, New Zealand punk band Blam Blam Blam, The Pogues, Thin Lizzy, Dub Syndicate, and the comedians Bill Bailey and Mitch Benn. Both the theme and obsessive fans were satirised on The Chaser's War on Everything. The theme tune has also appeared on many compilation CDs, and has made its way into mobile-phone ringtones. Fans have also produced and distributed their own remixes of the theme. In January 2011, the Mankind version was released as a digital download on the album Gallifrey And Beyond.[citation needed]

On 26 June 2018, producer Chris Chibnall announced that the musical score for series 11 would be provided by Royal Birmingham Conservatoire alumnus Segun Akinola.[203]

Incidental music

Most of the innovative incidental music for Doctor Who has been specially commissioned from freelance composers, although in the early years some episodes also used stock music, as well as occasional excerpts from original recordings or cover versions of songs by popular music acts such as The Beatles and The Beach Boys. Since its 2005 return, the series has featured occasional use of excerpts of pop music from the 1970s to the 2000s.[citation needed]

The incidental music for the first Doctor Who adventure, An Unearthly Child, was written by Norman Kay. Many of the stories of the William Hartnell period were scored by electronic music pioneer Tristram Cary, whose Doctor Who credits include The Daleks, Marco Polo, The Daleks' Master Plan, The Gunfighters and The Mutants. Other composers in this early period included Richard Rodney Bennett, Carey Blyton and Geoffrey Burgon.[citation needed]

The most frequent musical contributor during the first 15 years was Dudley Simpson, who is also well known for his theme and incidental music for Blake's 7, and for his haunting theme music and score for the original 1970s version of The Tomorrow People. Simpson's first Doctor Who score was Planet of Giants (1964) and he went on to write music for many adventures of the 1960s and 1970s, including most of the stories of the Jon Pertwee/Tom Baker periods, ending with The Horns of Nimon (1979). He also made a cameo appearance in The Talons of Weng-Chiang (as a Music hall conductor).[204]

In 1980 starting with the serial The Leisure Hive the task of creating incidental music was assigned to the Radiophonic Workshop. Paddy Kingsland and Peter Howell contributed many scores in this period and other contributors included Roger Limb, Malcolm Clarke and Jonathan Gibbs. The Radiophonic Workshop was dropped after 1986's The Trial of a Time Lord series, and Keff McCulloch took over as the series' main composer until the end of its run, with Dominic Glynn and Mark Ayres also contributing scores.[citation needed]

From the 2005 revival to the 2017 Christmas episode "Twice Upon a Time",[citation needed] all incidental music for the series was composed by Murray Gold and Ben Foster and has been performed by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales from the 2005 Christmas episode "The Christmas Invasion" onwards. A concert featuring the orchestra performing music from the first two series took place on 19 November 2006 to raise money for Children in Need. David Tennant hosted the event, introducing the different sections of the concert. Murray Gold and Russell T Davies answered questions during the interval, and Daleks and Cybermen appeared whilst music from their stories was played. The concert aired on BBCi on Christmas Day 2006. A Doctor Who Prom was celebrated on 27 July 2008 in the Royal Albert Hall as part of the annual BBC Proms. The BBC Philharmonic and the London Philharmonic Choir performed Murray Gold's compositions for the series, conducted by Ben Foster, as well as a selection of classics based on the theme of space and time. The event was presented by Freema Agyeman and guest-presented by various other stars of the show with numerous monsters participating in the proceedings. It also featured the specially filmed mini-episode "Music of the Spheres", written by Russell T Davies and starring David Tennant.[205]

Six soundtracks have been released since 2005. The first featured tracks from the first two series,[206][207] the second and third featured music from the third and fourth series respectively. The fourth was released on 4 October 2010 as a two-disc special edition and contained music from the 2008–2010 specials (The Next Doctor to "End of Time Part 2").[208][209] The soundtrack for Series 5 was released on 8 November 2010.[210] In February 2011, a soundtrack was released for the 2010 Christmas special "A Christmas Carol",[211] and in December 2011, the soundtrack for Series 6 was released, both by Silva Screen Records.[212]

In 2013, a 50th-anniversary boxed set of audio CDs was released featuring music and sound effects from Doctor Who's 50-year history. The celebration continued in 2016 with the release of Doctor Who: The 50th Anniversary Collection Four LP Box Set by New York City-based Spacelab9. The company pressed 1,000 copies of the set on "Metallic Silver" vinyl, dubbed the "Cyberman Edition".[213]

Viewership

United Kingdom

Premiering the day after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the first episode of Doctor Who was repeated with the second episode the following week.[214][215] Doctor Who has always appeared initially on the BBC's mainstream BBC One channel, where it is regarded as a family show, drawing audiences of many millions of viewers;[216][217] The programme's popularity has waxed and waned over the decades, with three notable periods of high ratings.[218] The first of these was the "Dalekmania" period (c. 1964–1965), when the popularity of the Daleks regularly brought Doctor Who ratings of between 9 and 14 million, even for stories which did not feature them.[218] The second was the mid to late 1970s, when Tom Baker occasionally drew audiences of over 12 million.[218]

During the ITV network strike of 1979, viewership peaked at 16 million.[219] Figures remained respectable into the 1980s, but fell noticeably after the programme's 23rd series was postponed in 1985 and the show was off the air for 18 months.[220]

Its late 1980s performance of three to five million viewers was seen as poor at the time and was, according to the BBC Board of Control, a leading cause of the programme's 1989 suspension. Some fans considered this disingenuous, since the programme was scheduled against the ITV soap opera Coronation Street, the most popular show at the time.[221][222] During Tennant's run (the third notable period of high ratings), the show had consistently high viewership, with the Christmas specials regularly attracting over 10 million.[218]

The BBC One broadcast of "Rose", the first episode of the 2005 revival, drew an average audience of 10.81 million, third highest for BBC One that week and seventh across all channels.[218][223][224] The current revival also garners the highest audience Appreciation Index of any drama on television.[225]

International

Doctor Who has been broadcast internationally outside of the United Kingdom since 1964, a year after the show first aired. As of November 2013[update], the modern series has been broadcast in more than 50 countries.[226] The 50th anniversary episode, "The Day of the Doctor", was broadcast in 94 countries and screened to more than half a million people in cinemas across Australia, Latin America, North America and Europe. The scope of the broadcast was a world record, according to Guinness World Records.[227]

Doctor Who is one of the five top-grossing titles for BBC Worldwide, the BBC's commercial arm.[228] BBC Worldwide CEO John Smith has said that Doctor Who is one of a small number of "Superbrands" which are heavily promoted worldwide.[229]

Only four episodes have premiere showings on channels other than BBC One. The 1983 20th-anniversary special "The Five Doctors" had its debut on 23 November (the actual date of the anniversary) on a number of PBS stations two days before its BBC One broadcast. The 1988 story Silver Nemesis was broadcast with all three episodes airing back to back on TVNZ in New Zealand in November, after the first episode had been shown in the UK but before the final two instalments had aired there.[citation needed]

Starting with the 60th-anniversary specials in 2023, Doctor Who has been released on Disney+ outside the United Kingdom and Ireland.[230]

Oceania

New Zealand was the first country outside the United Kingdom to screen Doctor Who, beginning in September 1964, and continued to screen the series for many years, including the new revived series that aired on Prime Television from 2005 to 2017.[231] In 2018, the series is aired on Fridays on TVNZ 2, and on TVNZ On Demand on the same episode as the UK.[232] The series moved to TVNZ 1 in 2021,[citation needed] before TVNZ lost the rights to the show altogether in 2022.[233]

In Australia, the show has had a strong fan base since its inception, having been exclusively first run by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) since January 1965. The ABC has periodically repeated episodes; of note were the daily screenings of all available classic episodes starting in 2003 for the show's 40th anniversary and the weekly screenings of all available revived episodes in 2013 for the show's 50th anniversary. The ABC broadcast the modern series' first run on ABC1 and ABC Me, with repeats on ABC2 and streaming available on ABC iview.[234]

Americas

The series also has a fan base in the United States, where it was shown in syndication from the 1970s to the 1990s, particularly on PBS stations.[235]

TVOntario picked up the show in 1976 beginning with The Three Doctors and aired each series (several years late) through to series 24 in 1991. From 1979 to 1981, TVO airings were bookended by science-fiction writer Judith Merril who introduced the episode and then, after the episode concluded, tried to place it in an educational context in keeping with TVO's status as an educational channel. Its airing of The Talons of Weng-Chiang was cancelled as a result of accusations that the story was racist; the story was later broadcast in the 1990s on cable station YTV. CBC began showing the series again in 2005. The series moved to the Canadian cable channel Space in 2009.[236]

Series three began broadcasting on CBC on 18 June 2007 followed by the second Christmas special, "The Runaway Bride", at midnight,[237] and the Sci Fi Channel began on 6 July 2007, starting with the second Christmas special at 8:00 pm E/P followed by the first episode.[238]

Series four aired in the United States on the Sci Fi Channel (now known as Syfy), beginning in April 2008.[239] It aired on CBC beginning 19 September 2008, although the CBC did not air the "Voyage of the Damned" special.[240] The Canadian cable network Space (now known as CTV Sci-Fi Channel) broadcast "The Next Doctor" (in March 2009) and all subsequent series and specials.[236]

The series was aired in Brazil at the TV networks Syfy and, more frequently, at the public broadcaster TV Cultura. Expect international distribution rights holders, it had already been made available on local streaming platforms Looke and Globoplay. Starting from 2024, the previous 13 series will be available at the upcoming streaming service +SBT.[241]

Asia

Series 1 through 3 of Doctor Who were broadcast on various NHK channels from 2006 to 2008 with Japanese subtitles.[242] Beginning on 2 August 2009, upon the launch of Disney XD in Japan, the series has been broadcast with Japanese dubbing.[243]

Home media

A wide selection of serials is available from BBC Video on DVD, on sale in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and the United States. Every fully extant serial has been released on VHS, and BBC Worldwide continues to regularly release serials on DVD. The 2005 series is also available in its entirety on UMD for the PlayStation Portable. Eight original series serials have been released on Laserdisc[244] and many have also been released on Betamax tape and Video 2000. One episode of Doctor Who (The Infinite Quest) was released on VCD. Initially, only the series from 2005 onwards were also available on Blu-ray, along with the 1996 TV film Doctor Who, released in September 2016.[245] However in March 2021, it was announced that the classic run would be released on Blu-ray starting with seasons 12 and 19.[246]

Over 600 episodes of the classic series (the first 8 Doctors, from 1963 to 1996) are available to stream on BritBox (launched in 2017) and Pluto TV.[247] From 2020, the revival series is available for streaming on HBO Max, as well as spin-offs Sarah Jane Adventures and Torchwood.[248] Ahead of the 60th anniversary of the series, BBC cleared the rights to allow almost every single non-missing episode of Doctor Who[l] onto iPlayer. Additionally various spin-offs were also added to iPlayer including Torchwood, The Sarah Jane Adventures, Class, and Doctor Who Confidential.[250]

Adaptations and other appearances

Films

There are two Dr. Who feature films: Dr. Who and the Daleks, released in 1965 and Daleks' Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. in 1966. Both are retellings of existing television stories (specifically, the first two Dalek serials, The Daleks and The Dalek Invasion of Earth respectively) with a larger budget and alterations to the series concept.[citation needed]

In these films, Peter Cushing plays a human scientist[251] named "Dr. Who" who travels with his granddaughter, niece, and other companions in a time machine he has invented. The Cushing version of the character reappears in both comic strips and a short story, the latter attempting to reconcile the film continuity with that of the series. In addition, several planned films were proposed, including a sequel, The Chase, loosely based on the original series story, for the Cushing Doctor, plus many attempted television movie and big-screen productions to revive the original Doctor Who after the original series was cancelled.[citation needed]

Paul McGann starred in the only television film as the eighth incarnation of the Doctor. After the film, he continued the role in audio dramas and was confirmed as the eighth incarnation through flashback footage and a mini episode in the 2005 revival, effectively linking the two series and the television movie.[citation needed]

In 2011, David Yates announced that he had started work with the BBC on a Doctor Who film, a project that would take three or more years to complete. Yates indicated that the film would take a different approach from Doctor Who,[252] although then showrunner Steven Moffat stated later that any such film would not be a reboot of the series and that a film should be made by the BBC team and star the current TV Doctor.[253]

Spin-offs

Doctor Who has appeared on stage numerous times. In the early 1970s, Trevor Martin played the role in Doctor Who and the Daleks in the Seven Keys to Doomsday. In the late 1980s, Jon Pertwee and Colin Baker both played the Doctor at different times during the run of a play titled Doctor Who – The Ultimate Adventure. For two performances, while Pertwee was ill, David Banks (better known for playing Cybermen) played the Doctor. Other original plays have been staged as amateur productions, with other actors playing the Doctor, while Terry Nation wrote The Curse of the Daleks, a stage play mounted in the late 1960s, but without the Doctor.[citation needed]

A pilot episode ("A Girl's Best Friend") for a potential spin-off series, K-9 and Company, aired in 1981, with Elisabeth Sladen reprising her role as companion Sarah Jane Smith and John Leeson as the voice of K9, but was not picked up as a regular series. Concept art for an animated Doctor Who series was produced by animation company Nelvana in the 1980s, but the series was not produced.[254][255]

Following the success of the 2005 series produced by Russell T Davies, the BBC commissioned Davies to produce a 13-part spin-off series titled Torchwood (an anagram of "Doctor Who"), set in modern-day Cardiff and investigating alien activities and crime. The series debuted on BBC Three on 22 October 2006.[256] John Barrowman reprised his role of Jack Harkness from the 2005 series of Doctor Who.[257] Two other actresses who appeared in Doctor Who also star in the series: Eve Myles as Gwen Cooper, who played the similarly named servant girl Gwyneth in the 2005 Doctor Who episode "The Unquiet Dead",[258] and Naoko Mori, who reprised her role as Toshiko Sato, first seen in "Aliens of London". A second series of Torchwood aired in 2008; for three episodes, the cast was joined by Freema Agyeman reprising her Doctor Who role of Martha Jones. A third series was broadcast from 6 to 10 July 2009, and consisted of a single five-part story called Children of Earth which was set largely in London. A fourth series, Torchwood: Miracle Day jointly produced by BBC Wales, BBC Worldwide and the American entertainment company Starz debuted in 2011. The series was predominantly set in the United States, though Wales remained part of the show's setting.[citation needed]

The Sarah Jane Adventures, starring Elisabeth Sladen who reprised her role as investigative journalist Sarah Jane Smith, was developed by CBBC; a special aired on New Year's Day 2007, and a full series began on 24 September 2007.[259] A second series followed in 2008, featuring the return of Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart.[260][261] A third in 2009 featured a crossover appearance from the main show by David Tennant as the Tenth Doctor.[262][263] In 2010, a fourth season featured Matt Smith as the Eleventh Doctor alongside former companion actress Katy Manning reprising her role as Jo Grant.[264] A final, three-story fifth series was transmitted in autumn 2011 – uncompleted due to Sladen's death in early 2011.[265]

An animated serial, The Infinite Quest, aired alongside the 2007 series of Doctor Who as part of the children's television series Totally Doctor Who. The serial featured the voices of series regulars David Tennant and Freema Agyeman but is not considered part of the 2007 series.[266] A second animated serial, Dreamland, aired in six parts on the BBC Red Button service, and the official Doctor Who website in 2009.[267]

Class, featuring students of Coal Hill School, was first aired on-line on BBC Three from 22 October 2016, as a series of eight 45 minute episodes, written by Patrick Ness.[268][269] Peter Capaldi as the Twelfth Doctor appears in the show's first episode.[citation needed] The series was picked up by BBC America on 8 January 2016 and by BBC One a day later.[270] On 7 September 2017, BBC Three controller Damian Kavanagh confirmed that the series had officially been cancelled.[271]

On 27 January 2023, Russell T Davies confirmed via GQ that future Doctor Who spin-offs were in the works.[272][273][274] At San Diego Comic-Con in July 2024, Davies confirmed a new spin-off series, The War Between the Land and the Sea, was in development.[275] Davies wrote the spin-off with Pete McTighe,[276] which will consist of five parts, and is set to be directed by Dylan Holmes Williams.[277][278] Jemma Redgrave and Alexander Devrient are expected to reprise their roles from Doctor Who as Kate Lethbridge-Stewart and Colonel Ibrahim,[279] while Russell Tovey and Gugu Mbatha-Raw, who portrayed characters in Doctor Who, were cast as new characters. The series is expected to see the return of the Sea Devils.[280]

Numerous other spin-off series have been created not by the BBC but by the respective owners of the characters and concepts. Such spin-offs include the novel and audio drama series Faction Paradox, Iris Wildthyme and Bernice Summerfield; as well as the made-for-video series P.R.O.B.E.; the Australian-produced television series K-9, which aired a 26-episode first season on Disney XD;[281] and the audio spin-off Counter-Measures.[282]

Aftershows

When the revived series of Doctor Who was brought back, an aftershow series was created by the BBC, titled Doctor Who Confidential. There have been three aftershow series created, with the latest one titled Doctor Who: The Fan Show, which began airing from the tenth series. Each series follows behind-the-scenes footage on the making of Doctor Who through clips and interviews with the cast, production crew and other people, including those who have participated in the television series in some manner. Each episode deals with a different topic, and in most cases refers to the Doctor Who episode that preceded it.[citation needed]

| Series | Episodes | First aired | Last aired | Narrator / Presenter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor Who Confidential | 87 | 26 March 2005 | 1 October 2011 | David Tennant (2005) Simon Pegg (2005) Mark Gatiss (2005–2006) Anthony Head (2006–2010) Noel Clarke (2009) Alex Price (2010) Russell Tovey (2010–2011) |

| Doctor Who Extra | 90 | 23 August 2014 | 5 December 2015 | Matt Botten Rufus Hound Matt Lucas Charity Wakefield |

| Doctor Who: The Fan Show | 166 | 8 May 2015 | 3 August 2018 | Christel Dee (main host) Luke Spillane (co-host) |

| Doctor Who Access All Areas | 10 | 13 October 2018 | 13 December 2018 | Yinka Bokinni |

| Doctor Who: Unleashed | 14 (+1 supplemental) | 17 November 2023 | present | Steffan Powell |

Charity episodes and appearances

In 1983, coinciding with the series' 20th anniversary, "The Five Doctors" was shown as part of the annual BBC Children in Need Appeal, however it was not a charity-based production, simply scheduled within the line-up of Friday 25 November 1983. This was the programme's first co-production with Australian broadcaster ABC.[283] At 90 minutes long it was the longest single episode of Doctor Who produced to date. It featured three of the first five Doctors, a new actor to replace the deceased William Hartnell, and unused footage to represent Tom Baker.[284]

In 1993, for the franchise's 30th anniversary, another charity special, Dimensions in Time, was produced for Children in Need, featuring all the surviving actors who played the Doctor and a number of previous companions. It also featured a crossover with the soap opera EastEnders, the action taking place in the latter's Albert Square location and around Greenwich. The special was one of several special 3D programmes the BBC produced at the time, using a 3D system that made use of the Pulfrich effect, requiring glasses with one darkened lens; the picture would look normal to those viewers who watched without the glasses.[citation needed]

In 1999, another special, Doctor Who and the Curse of Fatal Death, was made for Comic Relief and later released on VHS. An affectionate parody of the television series, it was split into four segments, mimicking the traditional serial format, complete with cliffhangers, and running down the same corridor several times when being chased (the version released on video was split into only two episodes).[citation needed] In the story, the Doctor (Rowan Atkinson) encounters both the Master (Jonathan Pryce) and the Daleks. During the special, the Doctor is forced to regenerate several times, with his subsequent incarnations played by, in order, Richard E. Grant, Jim Broadbent, Hugh Grant, and Joanna Lumley.[285] The script was written by Steven Moffat, later to be head writer and executive producer of the revived series.[286]

Since the return of Doctor Who in 2005, the franchise has produced two original "mini-episodes" to support Children in Need. The first, which aired in November 2005, was an untitled seven-minute scene introducing David Tennant as the Tenth Doctor. It was followed in November 2007 by "Time Crash", a 7-minute scene that featured the Tenth Doctor meeting the Fifth Doctor, Peter Davison.[287]

A set of two mini-episodes, titled "Space" and "Time" respectively, were produced to support Comic Relief. They were aired during the Comic Relief 2011 event.[288] During Children in Need 2011, an exclusively filmed segment showed the Doctor addressing the viewer, attempting to persuade them to purchase items of his clothing, which were going up for auction for Children in Need. Children in Need 2012 featured the mini-episode "The Great Detective".[289] In 2014, the Twelfth Doctor Peter Capaldi designed a Doctor Who-themed Paddington Bear statue, which was located at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich (one of 50 placed around London), which was auctioned to raise funds for the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC).[290][291]

Spoofs and cultural references

Doctor Who has been satirised and spoofed on many occasions by comedians including Spike Milligan (a Dalek invades his bathroom—Milligan, naked, hurls a soap sponge at it) and Lenny Henry. Jon Culshaw frequently impersonates the Fourth Doctor in the BBC Dead Ringers series.[292] Doctor Who fandom has also been lampooned on programs such as Saturday Night Live, The Chaser's War on Everything, Mystery Science Theater 3000, Family Guy, American Dad!, Futurama, South Park, Community as Inspector Spacetime, The Simpsons and The Big Bang Theory.[citation needed] As part of the 50th-anniversary programmes, former Fifth Doctor Peter Davison directed, wrote, and co-starred in the parody The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot, which also starred two other former Doctors, Colin Baker and Sylvester McCoy, and had cameo appearances from cast and crew involved in the programme, including showrunner Steven Moffat and Doctors Paul McGann, David Tennant, and Matt Smith.[293]

There have also been many references to Doctor Who in popular culture and other science fiction, including Star Trek: The Next Generation ("The Neutral Zone")[294] and Leverage. In the Channel 4 series Queer as Folk (created by later Doctor Who executive producer Russell T. Davies), the character of Vince was portrayed as an avid Doctor Who fan, with references appearing many times throughout in the form of clips from the programme. In a similar manner, the character of Oliver on Coupling (created and written by Steven Moffat) is portrayed as a Doctor Who collector and enthusiast. References to Doctor Who have also appeared in the young adult fantasy novels Brisingr[295] and High Wizardry,[296] the video game Rock Band,[citation needed] the Adult Swim comedy show Robot Chicken, the Family Guy episodes "Blue Harvest" and "420", and the game RuneScape. It has also been referenced in Destroy All Humans! 2, by civilians in the game's variation of England,[297] and multiple times throughout the Ace Attorney series.[298] It has been featured in Good Omens through the first Doctor Who Annual.[299]

Doctor Who has been a reference in several political cartoons, from a 1964 cartoon in the Daily Mail depicting Charles de Gaulle as a Dalek[300] to a 2008 edition of This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow in which the Tenth Doctor informs an incredulous character from 2003 that the Democratic Party will nominate an African-American as its presidential candidate.[301]

The word "TARDIS" is an entry in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.[302]

Audio

The earliest Doctor Who–related audio release was a 21-minute narrated abridgement of the First Doctor television story The Chase released in 1966. Ten years later, the first original Doctor Who audio was released on LP record; Doctor Who and the Pescatons featuring the Fourth Doctor.[303] The first commercially available audiobook was an abridged reading of the Fourth Doctor story State of Decay in 1981. In 1988, during a hiatus in the television show, Slipback, the first radio drama, was transmitted.[304]

Since 1999, Big Finish Productions has released several different series of Doctor Who audios on CD. The earliest of these featured the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Doctors, with Paul McGann's Eighth Doctor joining the line in 2001. Tom Baker's Fourth Doctor began appearing for Big Finish in 2012.[305] Along with the main range, adventures of the First, Second and Third Doctors have been produced in both limited cast and full cast formats, as well as audiobooks. The 2013 series Destiny of the Doctor, produced as part of the series' 50th-anniversary celebrations, marked the first time Big Finish created stories (in this case audiobooks) featuring the Doctors from the revived show.[citation needed] Along with this, in May 2016, the Tenth Doctor, David Tennant, appeared alongside Catherine Tate in a collection of three audio adventures,[306] before receiving his own range.[307][305] In August 2020, Big Finish announced a new series of audios beginning release in May 2021, featuring Christopher Eccleston reprising his role as the Ninth Doctor.[308][305]

The main range, Doctor Who: The Monthly Adventures, holds the Guinness World Record for the longest-running science fiction audio play series.[309][310] In 2020 Big Finish revealed that The Monthly Adventures would come to an end in favor of individual box sets.[311]

In 2022, BBC Sounds began airing Doctor Who: Redacted, a podcast written by Juno Dawson and starring Charlie Craggs and Jodie Whittaker. The podcast focuses on a trio of friends who host a paranormal conspiracy podcast, "The Blue Box Files", and end up getting involved in much more than they expected.[312][313] The podcast was later renewed for a second series.[314]

Books

Doctor Who books have been published from the mid-sixties through to the present day. From 1965 to 1991 the books published were primarily novelised adaptations of broadcast episodes; beginning in 1991 an extensive line of original fiction was launched, the Virgin New Adventures and Virgin Missing Adventures. Since the relaunch of the programme in 2005, a new range of novels has been published by BBC Books. Numerous non-fiction books about the series, including guidebooks and critical studies, have also been published,[citation needed] and a dedicated Doctor Who Magazine (DWM) with newsstand circulation has been published regularly since 1979: DWM is recognised by Guinness World Records as the longest running TV tie-in magazine, celebrating 40 years of continuous publication on 11 October 2019.[315] This is published by Panini, as is the Doctor Who Adventures magazine for younger fans.[316]

Video games

Numerous Doctor Who video games have been created from the mid-80s through to the present day. A Doctor Who game was planned for the Sega Mega Drive but never released.[317] One of the recent ones is a match-3 game released in November 2013 for iOS, Android, Amazon App Store and Facebook called Doctor Who: Legacy. It has been constantly updated since its release and features all the Doctors as playable characters as well as over 100 companions.[318]

Another video game instalment is Lego Dimensions – in which Doctor Who is one of the many "Level Packs" in the game. The pack contains the Twelfth Doctor (who can reincarnate into the others), K9, the TARDIS and a Victorian London adventure level area. The game and pack released in November 2015.[319]

Doctor Who: Battle of Time was a digital collectible card game developed by Bandai Namco Entertainment and released for iOS and Android.[320] It was soft-launched on 30 May 2018 in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Thailand, but was shut down on 26 November of that same year.[321]

Doctor Who Infinity was released on Steam on 7 August 2018.[322] It was nominated for "Best Start-up" at The Independent Game Developers' Association Awards 2018.[323][324]

Chronology and canonicity

Since the creation of the Doctor Who character by BBC Television in the early 1960s, a myriad of stories have been published about Doctor Who, in different media: apart from the actual television episodes that continue to be produced by the BBC, there have also been novels, comics, short stories, audio books, radio plays, interactive video games, game books, webcasts, DVD extras, and stage performances. The BBC takes no position on the canonicity of any of such stories, and producers of the show have expressed distaste for the idea of canonicity.[325]

Awards