Transnistria conflict

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Transnistria conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the post-Soviet conflicts | |||||||||

Moldova Transnistria | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|---|

| Constitution |

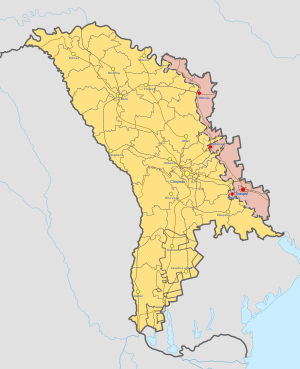

The Transnistria conflict (Romanian: Conflictul din Transnistria; Russian: Приднестровский конфликт, romanized: Pridnestrovsky konflikt; Ukrainian: Придністровський конфлікт, romanized: Prydnistrovskyi konflikt) is an ongoing frozen conflict between Moldova and the unrecognized state of Transnistria. Its most active phase was the Transnistria War. There have been several unsuccessful attempts to resolve the conflict.[10][11] The conflict may be considered to have started on 2 September 1990, when Transnistria made a formal sovereignty declaration from Moldova (then part of the Soviet Union).[12]

Transnistria is internationally recognized as a part of Moldova. It has diplomatic recognition only from two Russian-backed separatist states: Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Historical status of Transnistria

[edit]

Until the Second World War

[edit]The Soviet Union in the 1930s had an autonomous region of Transnistria inside Ukraine, called the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR), half of whose population were Romanian-speaking people, and with Tiraspol as its capital.[citation needed]

During World War II, when Romania, aided by Nazi Germany, took control of Transnistria, it did not attempt to annex the occupied territory during the war, although it planned do so in the future.[13][14]

Territorial consequences of the 1992 conflict

[edit]Left bank of the Dniester

[edit]During the War of Transnistria, some villages in the central part of Transnistria (on the eastern bank of the Dniester) rebelled against the new separatist Transnistria (PMR) authorities. They have been under effective Moldovan control as a consequence of their rebellion against the PMR. These localities are: commune Cocieri (including village Vasilievca), commune Molovata Nouă (including village Roghi), commune Corjova (including village Mahala), commune Coșnița (including village Pohrebea), commune Pîrîta, and commune Doroțcaia. The village of Corjova is in fact divided between PMR and Moldovan central government areas of control. Roghi is also controlled by the PMR authorities.[citation needed]

Right bank of the Dniester

[edit]At the same time, some areas on the right bank of the Dniester are under PMR control. These areas consist of the city of Bender with its suburb Proteagailovca, the communes Gîsca, Chițcani (including villages Mereneşti and Zahorna), and the commune of Cremenciug, formally[clarification needed] in the Căușeni District, situated south of the city of Bender.[citation needed]

The breakaway PMR authorities also claim the communes of Varnița, in the Anenii Noi District, a northern suburb of Bender, and Copanca, in the Căușeni District, south of Chițcani, but these villages remain under Moldovan control.[citation needed]

Later tensions

[edit]Several disputes have arisen from these cross-river territories. In 2005, PMR militia entered Vasilievca, which is located over the strategic road linking Tiraspol and Rîbnița, but withdrew after a few days.[15][16] In 2006 there were tensions around Varnița. In 2007 there was a confrontation between Moldovan and PMR forces in the Dubăsari-Cocieri area; however, there were no casualties. On 13 May 2007, the mayor of the village of Corjova, which is under Moldovan control, was arrested by the PMR militsia (police) together with a councilor of Moldovan-controlled part of the Dubăsari district.[17]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]Amid the prelude to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, on 14 January 2022 Ukrainian military intelligence declared that Russian special services were preparing "provocations" against Russian soldiers stationed in Transnistria at the time to create a casus belli for a Russian invasion of Ukraine.[18]

On 24 February, on the first day of the invasion, there were allegations that some rockets that had hit Ukraine had been launched from Transnistria, although Moldova's Ministry of Defense denied this.[19] On 4 March, Ukraine blew up a railway bridge on its border with Transnistria to prevent the 1,400 Russian troops stationed in the breakaway territory from crossing into Ukraine.[20] Later, on 6 March, there were again claims that attacks that had hit Vinnytsia's airport had been launched from Transnistria, although Moldovan officials again denied this and said that they had been launched from Russian ships in the Black Sea.[21]

Amid rumors that Transnistria would attack Ukraine, Transnistrian President Vadim Krasnoselski declared Transnistria to be a peaceful state which never had any plans to attack its neighbors and that those who spread these allegations were people without control over the situation or provocateurs with malicious intentions. He also made reference to the large ethnically Ukrainian population of Transnistria and how Ukrainian is taught in Transnistrian schools and is one of the official languages of the republic.[22] However, in March, an image of the Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko standing in front of a battle plan map of the invasion of Ukraine was leaked. This map showed a supposed incursion of Russian troops from the Ukrainian city port of Odesa into Transnistria and Moldova, revealing that Transnistria could become involved in the war.[23]

Ukrainian military officials had identified the establishment of a "land corridor" to Transnistria as one of Russia's primary objectives since the first day of the invasion.[24] On 22 April 2022, Russia's Brigadier General Rustam Minnekayev in a defence ministry meeting said that Russia planned to extend its Mykolaiv–Odesa front in the Ukraine war further west to include the Transnistria on the Ukrainian border with Moldova.[25][26] Minnekaev announced that the plan of Russia's military action in Ukraine included taking full control of Southern Ukraine and achieving a land corridor to Transnistria. He also talked about the existence of supposed evidence of "oppression of the Russian-speaking population" of Transnistria, echoing Russia's justifications for the war in Ukraine.[27] The Ministry of Defence of Ukraine described this intention as imperialism, saying that it contradicted previous Russian claims that it did not have territorial ambitions in Ukraine".[25]

On 26 April, Ukrainian presidential adviser Oleksiy Arestovych said during an interview that Moldova was a close neighbor to Ukraine, that Ukraine was not indifferent to it and that Moldova could turn to Ukraine for help. He also declared that Ukraine was able to solve the problem of Transnistria "in the blink of an eye", but only if Moldovan authorities requested the country's help; and that Romania could also come to Moldova's aid as "they are in fact the same people", with the same language as he continued, even though "there are many Moldovans who would not agree with me".[5] Moldova officially rejected this suggestion from Ukraine, expressing its support only for a peaceful outcome of the conflict.[28]

On 12 September 2024, a Moldovan soldier was killed under unclear circumstances in the demarcation line of Transnistria.[29]

On 29 December 2024, Moldova's Transdniestria region faced gas cuts as a transit deal with Ukraine expired, prompting fears of power shortages. Moldova denies owing debts to Gazprom and is securing alternative supplies from Romania to manage the situation.[30]

Position of the PMR government advocates

[edit]According to PMR advocates, the territory to the east of the Dniester River never belonged either to Romania nor to its predecessors, such as the Principality of Moldavia. This territory was split off from the Ukrainian SSR in a political maneuver of the USSR to become a seed of the Moldavian SSR (in a manner similar to the creation of the Karelo-Finnish SSR). In 1990, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian SSR was proclaimed in the region by a number of conservative local Soviet officials opposed to perestroika. This action was immediately declared void by the then General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev.[31]

At the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Moldova became independent. The Moldovan Declaration of Independence denounced the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and declared the 2 August 1940 "Law of the USSR on the establishment of the Moldavian SSR" null and void. The PMR side argues that, since this law was the only legislative document binding Transnistria to Moldova, there is neither historical nor legal basis for Moldova's claims over the territories on the left bank of the Dniester.[32]

A 2010 study conducted by the University of Colorado Boulder showed that the majority of Transnistria's population supports the country's separation from Moldova. According to the study, more than 80% of ethnic Russians and Ukrainians and 60% of ethnic Moldovans in Transnistria preferred independence or annexation by Russia to reunification with Moldova.[33]

In 2006, officials of the country held a referendum to determine the status of Transnistria. There were two statements on the ballot: the first one was, "Renunciation of independence and potential future integration into Moldova"; the second was, "Independence and potential future integration into Russia". The results of this double referendum were that a large section of the population was against the first statement (96.61%)[34] and in favor of the second one (98.07%).[35]

Moldovan position

[edit]Moldova lost de facto control of Transnistria in 1992, in the wake of the War of Transnistria. However, the Republic of Moldova considers itself the rightful successor state to the Moldavian SSR (which was guaranteed the right to secession from the Soviet Union under the last version of the Soviet Constitution). By the principle of territorial integrity, Moldova claims that any form of secession from the state without the consent of the central Moldovan government is illegal.[citation needed] The Moldavian side hence believes that its position is backed by international law.[36] It considers the current Transnistria-based PMR government to be illegitimate and not the rightful representative of the region's population, which has a Moldovan plurality (39.9% as of 1989).[37] The Moldovan side insists that Transnistria cannot exist as an independent political entity and must be reintegrated into Moldova.[citation needed]

According to Moldovan sources, the political climate in Transnistria does not allow the free expression of the will of the people of the region and supporters of reintegration of Transnistria in Moldova are subjected to harassment, arbitrary arrests and other types of intimidation from separatist authorities.[citation needed]

Because of the non-recognition of Transnistria's independence, Moldova believes that all inhabitants of Transnistria are legally citizens of Moldova. However, it is estimated that 60,000 to 80,000 inhabitants of Transnistria have acquired Russian citizenship[38] and around 20,000 have acquired Ukrainian citizenship. As a result, Moldovan authorities have tried to block the installation of a Russian and Ukrainian consulate in Tiraspol.[38]

International recognition of Transnistria

[edit]Only two states recognize Transnistria's sovereignty, each itself a largely unrecognized state: Abkhazia and South Ossetia. These two states are members of the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.

On 21 February 2023, Russian president Vladimir Putin revoked the foreign policy document that declared Russian commitment to Moldovan sovereignty in the context of the Transnistria conflict.[39][40]

Positions taken by states

[edit]| State | Notes |

|---|---|

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Albania supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Officially, Belarus does not recognise Transnistria as independent.[42] De facto, Belarusian corporations and officials treat Transnistria as independent.[43][44][45][46][47][48] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Bosnia supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Croatia supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Georgia supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Liechtenstein supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Moldova's Prime Minister Vlad Filat wanted to see the Russian army presence replaced with an international civil mission and hoped for European support.[49] Deputy Prime Minister Victor Osipov said that Moldova was a European problem. When the EU passed the Lisbon Treaty and created the new position of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy he said "The results of these efforts (to have more powerful tools for an effective foreign policy) will be very important, along with the place that the Transnistrian problem will occupy on the agenda of the EU and its new institution. Our task here is to attract attention to the Transnistrian problem, precisely so that it will occupy a higher place in the foreign and security policy agenda of the EU. We will always seek a solution through peaceful means, but we should never forget that we are talking about a conflict. We are talking about an administration [in the city of Tiraspol] that has and is developing military capabilities and a very fragile situation that could deteriorate and create risky situations in the East of Europe. This affects the Republic of Moldova, Ukraine, Russia and Romania – because Romania is not indifferent to the developments – and other countries from the region. Experiences from other frozen conflicts show that it is not a good idea to wait until a major incident happens."[50] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Montenegro supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, North Macedonia supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Norway supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| During a visit to Kyiv, President Dmitri Medvedev said he supported "special status" for Transnistria and recognised the "important and stabilising" role of the Russian army.[49] There have been calls from Russian figures to recognize the separatist republic.[51] However, to date, Russia officially recognizes Moldovan sovereignty over Transnistria. | |

| Initially, Serbia, along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] In November 2015 Serbian politicians participated in a conference in Tiraspol. At the end of the conference, those politicians adopted a resolution which proclaimed that the "Transnistrian Moldovan Republic (PMR) and the Republic of Serbia are interested in broadening their multifaceted cooperation with the Russian Federation, including in the military-political sphere."[52] | |

| Along with other states on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, Turkey supported "renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova."[41] | |

| In June 1992, then Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk said that Ukraine would guarantee the independence of Transnistria in case of a Moldovan-Romanian union.[53] Over the following two decades Ukraine had an ambivalent relationship with Transnistria. In 2014, then Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko has said that Pridnestrovie is not a sovereign state, but rather, the name of a region along the Ukraine–Moldova border.[54] In 2017, Transnistrian president Vadim Krasnoselsky said that Transnistria had "traditionally good relations with (Ukraine), we want to maintain them" and "we must build our relations with Ukraine – this is an objective necessity".[55] |

Positions taken by international organizations

[edit]| Organization | Notes |

|---|---|

| In June 2015, the Secretary General of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Nikolay Bordyuzha, said that "[there] is no military solution to [the] Transnistria conflict. If a war breaks out in the region it will last for a long time and cause great bloodshed."[56] | |

| European Union took note of and welcomed "the objectives of Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova".[41] The EU was asked to restart negotiations for the 5+2 format.[49] |

United Nations Resolution A/72/L.58

[edit]

On 22 June 2018, the Republic of Moldova submitted a UN resolution that calls for "Complete and unconditional withdrawal of foreign military forces from the territory of the Republic of Moldova, including Transnistria." The resolution was adopted by a simple majority.[57]

See also

[edit]- Four Pillars of Transnistria

- War of Transnistria

- 2006 Transnistrian customs crisis

- International recognition of Transnistria

- Foreign relations of Transnistria

- Moldovan neutrality

- Abkhaz–Georgian conflict

- Gagauzia conflict

- Georgian–Ossetian conflict

- Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

References

[edit]- ^ Adam, Vlad (2017). Romanian involvement in the Transnistrian War (Thesis). Leiden University. pp. 1–31.

- ^ "Iohannis: Națiunile Unite nu trebuie să tolereze conflictul din Transnistria". Agora (in Romanian). 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine's stance on Transnistria remains unchanged – Zelensky". Ukrinform. 12 January 2021.

- ^ "Ukraine helps Moldova regain control over border in Transnistrian region". Euromaidan Press. 21 July 2017.

- ^ a b Ioniță, Tudor (27 April 2022). "VIDEO // Arestovici: Ucraina poate rezolva problema transnistreană "cât ai pocni din degete", dar trebuie ca R. Moldova să-i ceară ajutorul". Deschide.MD (in Romanian).

- ^ O'Reilly, Kieran; Higgins, Noelle (2008). "The role of the Russian Federation in the Pridnestrovian conflict: an international humanitarian law perspective". Irish Studies in International Affairs. 19. Royal Irish Academy: 57–72. doi:10.3318/ISIA.2008.19.57. JSTOR 25469836. S2CID 154866746.

- ^ Munteanu, Anatol (2020). "The hybrid warfare triggered by Russian Federation in the Republic of Moldova". Editura Academiei Oamenilor de Știință din România. 12 (1): 129–162.

- ^ "Russia defends "peacekeepers" the new Moldovan president wants out". Polygraph.info. 7 December 2020.

- ^ Kosienkowski, Marcin; Schreiber, William (8 May 2012). Moldova: Arena of International Influences. Lexington. ISBN 9780739173923. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Cojocaru, Natalia (2006). "Nationalism and identity in Transnistria". Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research. 19 (3–4): 261–272. doi:10.1080/13511610601029813. S2CID 53474094.

- ^ Roper, Steven D. (2001). "Regionalism in Moldova: the case of Transnistria and Gagauzia". Regional & Federal Studies. 11 (3): 101–122. doi:10.1080/714004699. S2CID 154516934.

- ^ Blakkisrud, Helge; Kolstø, Pål (2013). "From secessionist conflict toward a functioning state: processes of state- and nation-building in Transnistria". Post-Soviet Affairs. 27 (2): 178–210. doi:10.2747/1060-586X.27.2.178. S2CID 143862872.

- ^ Charles King: "The Moldovans", Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, California, 1999, page 93

- ^ Memoirs of Gherman Pântea, mayor of Odessa 1941–1944, in ANR-DAIC, d.6

- ^ "Moldova Azi". Archived from the original on 14 May 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2006.

- ^ "Locuitorii satului Vasilievca de pe malul stâng al Nistrului trăiesc clipe de coșmar". Archived from the original on 18 March 2005. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ "Ineffectiveness of peacekeeping mechanism leads to incidents in Moldova's Security Zone". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "Russia is preparing a pretext for invading Ukraine: US official". Al Jazeera English. 14 January 2022.

- ^ "Moldova tightens security after explosions heard close to Russia-backed Transnistria". Intellinews. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Ernst, Iulian (7 March 2022). "Ukraine blows up bridge to Transnistria after Tiraspol reasserts its independence". intellinews. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Missiles which hit Vinnytsia were not launched from the Transnistria – Ministry of Defence of Moldova". Ukrayinska Pravda. 6 March 2022.

- ^ Antonescu, Bogdan (26 February 2022). "Liderul de la Tiraspol, Vadim Krasnoselski: Transnistria este un stat pașnic. Nu am avut niciodată planuri de natură agresivă față de vecinii noștri" [Tiraspol leader Vadim Krasnoselski: Transnistria is a peaceful state. We have never had aggressive plans against our neighbors]. stiripesurse.ro (in Romanian).

- ^ Mitchell, Ellen (1 March 2022). "Belarus president stands in front of map indicating Moldova invasion plans". The Hill.

- ^ "Російські війська хочуть прорватися до Миколаєва, йдуть бої в околицях Чернігова". Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 24 February 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ a b Hubenko, Dmytro (22 April 2022). "Russia eyes route to Trans-Dniester: What do we know?". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "Russia plans to seize Donbas, southern Ukraine: Military official". Al Jazeera. 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Moldova holds urgent security meeting after Transnistria blasts". Aljazeera. 26 April 2022.

- ^ Ernst, Iulian (28 April 2022). "Moldova rejects Ukraine's offer to seize Transnistria". bne IntelliNews.

- ^ "A Moldovan soldier was killed in an incident on the demarcation line with Transnistria".

- ^ "Moldova's separatist region cuts gas as Ukraine transit deal runs out". Reuters. 29 December 2024. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ "UN and OSCE: Pridnestrovie is "different" and "distinct"". Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ "Moldova: "null and void" merging with Pridnestrovie". Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ "How people in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria feel about annexation by Russia". Washington Post. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ ch, Beat Müller, beat (at-sign) sudd (dot) (17 September 2006). "Transnistrische Moldawische Republik (Moldawien), 17. September 2006 : Verzicht auf Unabhängigkeit – [in German]". www.sudd.ch. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ch, Beat Müller, beat (at-sign) sudd (dot) (17 September 2006). "Transnistrische Moldawische Republik (Moldawien), 17. September 2006 : Unabhängigkeitskurs und Beitritt zu Russland – [in German]". www.sudd.ch. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Looking for a Solution Under International Law for the Moldova – Transnistria Conflict". Opinio Juris. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Transnistria (unrecognised state)". Refworld. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Moldova and Russia: Whether a holder of Ukrainian citizenship, born in Tiraspol, could return to Tiraspol and acquire Russian citizenship (2005)". Refworld. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Tanas, Alexander (22 February 2023). "Putin cancels decree underpinning Moldova's sovereignty in separatist conflict". Reuters.

- ^ "Russia's Putin cancels decree underpinning Moldova sovereignty in separatist conflict". 22 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Declaration by the Presidency on behalf of the European Union on the Council Common Position 2009/139/CFSP of 16 February 2009, renewing restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 13 March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Vladislav V. Froltsov: Belarus: A Pragmatic Approach toward Moldova, in: Marcin Kosienkowski, William Schreiber (ed.): Moldova: Arena of International Influences, Lanham (Maryland) 2012, pp. 1-12 (here: p. 2).

- ^ Belarus, Transnistria to foster cooperation, eng.belta.by 29 May 2013.[permanent dead link] Copy of the article.

- ^ Belarus’ companies ready to expand cooperation with Transnistria, eng.belta.by 26 April 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Belarus mulls transport engineering, farm projects in Transnistria, eng.belta.by 18 December 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Minsk donates buses, trolleybuses, ambulances to Tiraspol, eng.belta.by 14 August 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Minsk is ready to continue cooperation with Tiraspol, novostipmr.com 13 January 2016.

- ^ Президент ПМР провел встречу с Комиссаром по правам человека в Республике Беларусь, president.gospmr.org 31 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Transnistrian conflict: Russia and Ukraine talk about "coordinated effort" | Russia in Foreign Media | RIA Novosti". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Moldova Deputy PM: Transnistria is a European problem | EurActiv". Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Botnarenco, Iurii (18 November 2020). "Primele atacuri din Rusia după victoria Maiei Sandu. Jirinovski: Chișinăul va încerca să ocupe Transnistria pe cale militară. Trebuie să o apărăm". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- ^ Transnistria and Serbia confirm interest to cooperate with Russia, infotag.md 27 November 2015.

- ^ Moldawiens Präsident: Wir haben Krieg mit Rußland, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 23.06.1992.

- ^ "Не существует государства ПМР, существует лишь приднестровский участок границы - Порошенко". UNIAN (in Russian). 23 October 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Президент Приднестровья рассказал, почему не подпишет "Меморандум Козака-2", mk.ru 9. November 2017.

- ^ "CSTO secretary general: Any war in Karabakh and Transnistria will last for long time and cause great bloodshed, en.apa.az 18 June 2015". Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "General Assembly of the United Nations". www.un.org. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Oleksandr Pavliuk, Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze (2004). The Black Sea Region: Cooperation and Security Building. EastWest Institute. ISBN 0-7656-1225-9.

- Janusz Bugajski (2002). Toward an Understanding of Russia: New European Perspectives. Council on Foreign Relations Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-87609-310-1.

- "Transnistria: alegeri nerecunoscute". Ziua. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006.

- James Hughes; Gwendolyn Sasse, eds. (2002). Ethnicity and Territory in the Former Soviet Union: Regions in conflict. Routledge ed. ISBN 0-7146-5226-1.

External links

[edit]- Transnistrian side

- History of creation and development of the Parliament of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR)

- Moldovan side

- EuroJournal.org's Transnistria category Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Trilateral Plan for Solving the Transnistrian Issue (developed by Moldova-Ukraine-Romania expert group)

- Others

- International organizations

- OSCE Mission to Moldova: Conflict resolution and negotiation category

- Marius Vahl and Michael Emerson, "Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict" (pdf) in "Europeanization and Conflict Resolution: Case Studies from the European Periphery", JEMIE – Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 1/2004, Ghent, Belgium

- Research on the European Union and the conflict in Transnistria

- New York City Bar: Russia’s Activities in Moldova Violate International Law

- Ukrainian side

- Romanian side

- Transnistria conflict

- History of Moldova since 1991

- History of Transnistria since 1991

- Moldova–Russia relations

- Conflicts in territory of the former Soviet Union

- Politics of Transnistria

- Politics of Moldova

- Wars involving Moldova

- Wars involving Russia

- 20th-century conflicts

- 21st-century conflicts

- 1990s conflicts

- 2000s conflicts

- 2010s conflicts

- 2020s conflicts