List of African dinosaurs

This is a list of non-avian dinosaurs whose remains have been recovered in Africa. Africa has a rich fossil record. It is rich in Triassic and Early Jurassic dinosaurs. African dinosaurs from these time periods include Megapnosaurus, Dracovenator, Melanorosaurus, Massospondylus, Euskelosaurus, Heterodontosaurus, Abrictosaurus, and Lesothosaurus. In the Middle Jurassic, the sauropods Atlasaurus, Chebsaurus, Jobaria, and Spinophorosaurus, flourished, as well as the theropod Afrovenator. The Late Jurassic is well represented in Africa, mainly thanks to the spectacular Tendaguru Formation in Lindi Region of Tanzania. Veterupristisaurus, Ostafrikasaurus, Elaphrosaurus, Giraffatitan, Dicraeosaurus, Janenschia, Tornieria, Tendaguria, Kentrosaurus, and Dysalotosaurus are among the dinosaurs whose remains have been recovered from Tendaguru. This fauna seems to show strong similarities to that of the Morrison Formation in the United States and the Lourinha Formation in Portugal. For example, similar theropods, ornithopods and sauropods have been found in both the Tendaguru and the Morrison. This has important biogeographical implications.

The Early Cretaceous in Africa is known primarily from the northern part of the continent, particularly Niger. Suchomimus, Elrhazosaurus, Rebbachisaurus, Nigersaurus, Kryptops, Nqwebasaurus, and Paranthodon are some of the Early Cretaceous dinosaurs known from Africa. The Early Cretaceous was an important time for the dinosaurs of Africa because it was when Africa finally separated from South America, forming the South Atlantic Ocean. This was an important event because now the dinosaurs of Africa started developing endemism because of isolation. The Late Cretaceous of Africa is known mainly from North Africa. During the early part of the Late Cretaceous, North Africa was home to a rich dinosaur fauna. It includes Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, Rugops, Bahariasaurus, Deltadromeus, Paralititan, Aegyptosaurus, and Ouranosaurus.

Criteria for inclusion

[edit]- The genus must appear on the List of dinosaur genera.

- At least one named species of the creature must have been found in Africa.

- This list is a complement to Category:Mesozoic dinosaurs of Africa.

List of African dinosaurs

[edit]Valid genera

[edit]| Name | Year | Formation | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aardonyx | 2010 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian) | Primarily bipedal but also capable of quadrupedal locomotion |

| |

| Abrictosaurus | 1975 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | Known from two skulls, one of which possesses tusks, which may be an indication of sexual dimorphism[1] |

| |

| Adratiklit | 2020 | El Mers Group (Middle Jurassic, Bathonian to Callovian?) | One of the oldest known stegosaurs. Related to Late Jurassic European forms despite its early age[2] |

| |

| Aegyptosaurus | 1932 | Bahariya Formation, Continental intercalaire?, Farak Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Its holotype specimen was destroyed in World War II |

| |

| Afromimus | 2017 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Originally described as an African ornithomimosaur,[3] but later redescribed as a possible noasaurid[4] |

| |

| Afrovenator | 1994 | Tiourarén Formation (Middle Jurassic to Late Jurassic, Bathonian to Oxfordian) | Originally thought to hail from the Early Cretaceous |

| |

| Ajnabia | 2021 | Ouled Abdoun Basin (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | The first hadrosaurid known from Africa. Closely related to European lambeosaurines[5] |

| |

| Algoasaurus | 1904 | Kirkwood Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian to Valanginian) | Today known from only a few bones. Several more may have been made into bricks before they could be studied[6] |

| |

| Angolatitan | 2011 | Itombe Formation (Late Cretaceous, Coniacian) | The first non-avian dinosaur described from Angola |

| |

| Antetonitrus | 2003 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian) | Had weight-bearing adaptations in all its limbs, although its forelimbs retain adaptations for grasping |

| |

| Arcusaurus | 2011 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian) | Combines traits of basal and advanced sauropodomorphs |

| |

| Atlasaurus | 1999 | Guettioua Formation (Middle Jurassic, Bathonian to Callovian) | Possessed relatively elongated legs for a sauropod |

| |

| Australodocus | 2007 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | Potentially an early euhelopodid[7] |

| |

| Bahariasaurus | 1934 | Bahariya Formation, Farak Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | Large but known from very few remains |

| |

| Berberosaurus | 2007 | Azilal Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | One of the oldest known ceratosaurs |

| |

| Blikanasaurus | 1985 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | A "hyper-robust" form that niche partitioned with other Late Triassic Elliot Formation sauropodomorphs[8] |

| |

| Carcharodontosaurus | 1931 | Bahariya Formation, Chenini Formation?, Continental intercalaire, Echkar Formation, Elrhaz Formation?, Kem Kem Group, Wadi Milk Formation? (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | One of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs. Two species are known |

| |

| Chebsaurus | 2005 | Aïssa Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) | Known from two juvenile specimens |

| |

| Chenanisaurus | 2017 | Ouled Abdoun Basin (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Potentially represents a lineage of abelisaurids endemic to Africa |

| |

| Cristatusaurus | 1998 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Usually seen as a synonym of Suchomimus, although some studies consider it to be a valid genus[9] |

| |

| Deltadromeus | 1996 | Kem Kem Group (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Its precise phylogenetic position has been historically unstable, with multiple interpretations being suggested in the scientific literature[10][11][12][13] |

| |

| Dicraeosaurus | 1914 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | A short-necked, low-browsing sauropod. Two species are known |

| |

| Dracovenator | 2005 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian) | Only known from fragments of a skull, but those are enough to tell that it was related to Dilophosaurus |

| |

| Dysalotosaurus | 1919 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian) | Known from multiple remains that revealed much about its life history,[14] diet[15] and even disease[16] |

| |

| Elaphrosaurus | 1920 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian) | Possessed a relatively shallow chest for a medium-sized theropod |

| |

| Elrhazosaurus | 2009 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Closely related to Valdosaurus |

| |

| Eocarcharia | 2008 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Its frontal bone was swollen into a thick band, which gave it a menacing glare |

| |

| Eocursor | 2007 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian) | One of the most completely known early ornithischians |

| |

| Eucnemesaurus | 1920 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian to Norian) | Some fossils assigned to this genus were originally interpreted as those of a giant herrerasaurid |

| |

| Euskelosaurus | 1866 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian to Rhaetian) | Originally thought to have been bow-legged |

| |

| Geranosaurus | 1911 | Clarens Formation (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian to Toarcian) | Poorly known but potentially a heterodontosaurid |

| |

| Giraffatitan | 1988 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | Popularly associated with Brachiosaurus but several differences between the two have been noted[17] |

| |

| Gryponyx | 1911 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | Although usually seen as a synonym of Massospondylus, at least one study has found it to be distantly related[18] |

| |

| Heterodontosaurus | 1962 | Clarens Formation, Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | Possessed three types of teeth, including analogues of incisors and tusks, as well as a keratinous beak |

| |

| Igai | 2023 | Quseir Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | More closely related to European titanosaurs than to southern African ones |

| |

| Ignavusaurus | 2010 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian) | Only known from a single, mostly articulated juvenile skeleton with a badly crushed skull |

| |

| Inosaurus | 1960 | Bahariya Formation?, Eckhar Formation?, Tegama Group? (Early Cretaceous, Albian?) | Very poorly known | ||

| Iyuku | 2022 | Kirkwood Formation (Early Cretaceous, Valanginian) | Uniquely known from an assemblage of mostly hatchling and juvenile fossils | ||

| Janenschia | 1991 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | Potentially a close relative of Bellusaurus, Haestasaurus and Tehuelchesaurus, all of which may form a unique clade of eusauropods with possible turiasaur affinities[7][19][20] |

| |

| Jobaria | 1999 | Tiourarén Formation (Middle Jurassic to Late Jurassic, Bathonian to Oxfordian) | Known from an almost complete skeleton |

| |

| Kangnasaurus | 1915 | Kalahari Deposits Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Comparisons have been made with dryosaurids[21] but at least two studies suggest a position within Elasmaria[22][23] |

| |

| Karongasaurus | 2005 | Dinosaur Beds (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Described from only a mandible and isolated teeth |

| |

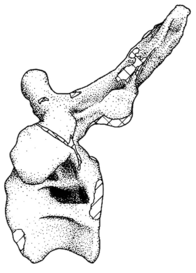

| Kentrosaurus | 1915 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | Possessed two rows of plates that gradually transitioned into spikes towards the tail, as well as a long spike on each shoulder |

| |

| Kholumolumo | 2020 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Before its formal description, it had been informally referred to as "Kholumolumosaurus" and "Thotobolosaurus". The latter name means "trash heap lizard" in Sesotho, referring to how the holotype was originally found close to a trash heap |

| |

| Kryptops | 2008 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Postcranial remains referred to this genus may have instead come from a carcharodontosaurid[24] |

| |

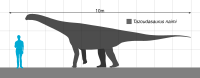

| Ledumahadi | 2018 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | One of the largest Early Jurassic dinosaurs, estimated as weighing 12 tonnes (26,000 lb) despite lacking columnar limbs like later sauropods[25] |

| |

| Lesothosaurus | 1978 | Clarens Formation, Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | Possibly an opportunistic omnivore, feeding on meat during seasons when plants are not available[26] |

| |

| Lurdusaurus | 1999 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | The proportions of its body and limbs suggest it may have been a semiaquatic herbivore similar to a hippopotamus[27] |

| |

| Lycorhinus | 1924 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | Originally misidentified as a cynodont |

| |

| Malawisaurus | 1993 | Dinosaur Beds (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Known from abundant material, including elements from the skull and osteoderms, but they may not represent a single taxon[28] |

| |

| Mansourasaurus | 2018 | Quseir Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | One of the few Late Cretaceous sauropods known from Africa[29] |

| |

| Massospondylus | 1854 | Bushveld Sandstone, Clarens Formation, Elliot Formation, Forest Sandstone (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Pliensbachian) | Abundant remains have been discovered. Several specimens were once assigned to their own genera and species |

| |

| Mbiresaurus | 2022 | Pebbly Arkose Formation (Late Triassic, Carnian) | One of the oldest dinosaurs known from Africa. Its discovery proves that the earliest dinosaurs were restricted to high latitudes[30] | ||

| Melanorosaurus | 1924 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | A robust, quadrupedal herbivore. Some specimens assigned to this genus may not represent the same taxon[8] |

| |

| Meroktenos | 2016 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian to Rhaetian) | Its femur was unusually robust for an animal of its size |

| |

| Minqaria | 2024 | Ouled Abdoun Basin (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Known from a partial skull |

| |

| Mnyamawamtuka | 2019 | Galula Formation (Early Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous, Aptian to Cenomanian) | Its specific name, moyowamkia, is Kiswahili for "heart tail", which references the heart-shaped cross-section of its caudal vertebrae |

| |

| Musankwa | 2024 | Pebbly Arkose Formation, (Late Triassic, Norian) | The fourth dinosaur genus to be named from Zimbabwe |

| |

| Ngwevu | 2019 | Clarens Formation (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian to Toarcian) | Known from a skull originally assigned to Massospondylus. It was assigned to its own genus based on its unique proportions |

| |

| Nigersaurus | 1999 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | All of its teeth were at the front of its jaws, which were wider than the rest of its skull, an adaptation to low browsing |

| |

| Nqwebasaurus | 2000 | Kirkwood Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian) | The first non-avian coelurosaur named from mainland Africa |

| |

| Orosaurus | 1867 | Elliot Formation? (Late Triassic, Norian to Rhaetian) | Probably a synonym of Euskelosaurus | ||

| Ostafrikasaurus | 2012 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian) | Described from a single tooth as an early spinosaurid[31] but ceratosaurid affinities have also been proposed[32] |

| |

| Ouranosaurus | 1976 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Had long neural spines that projected from its vertebrae, which may have supported a sail or hump in life |

| |

| Paralititan | 2001 | Bahariya Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Would have lived in a tidal flat environment dominated by mangroves |

| |

| Paranthodon | 1929 | Kirkwood Formation (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian to Valanginian) | Although only known from fragmentary specimens, they are enough to tell that it was a stegosaur |

| |

| Pegomastax | 2012 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian) | The morphology of its jaws and beak suggests a diet of tough plants |

| |

| Plateosauravus | 1932 | Elliot Formation (Late Triassic, Norian) | Known from multiple specimens, including those of juveniles |

| |

| Pulanesaura | 2015 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian to Sinemurian) | A low browser that lacked the extremely long neck of later sauropods |

| |

| Rebbachisaurus | 1954 | Kem Kem Group (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Carried a row of elongated neural spines, which would have supported a ridge or low sail on its back |

| |

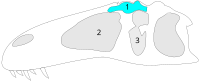

| Rugops | 2004 | Echkar Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Preserves two rows of holes on the top of its skull, which may have anchored a display structure[33] or an armor-like dermis[34] |

| |

| Rukwatitan | 2014 | Galula Formation (Early Cretaceous to Late Cretaceous, Albian to Cenomanian) | One of the few titanosaurs known from central Africa, filling in a gap in their evolutionary history |

| |

| Sauroniops | 2012 | Kem Kem Group (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Only known from a single, thickened frontal. Suggested to be a synonym of Carcharodontosaurus[13] but this has been refuted[35] |

| |

| Sefapanosaurus | 2015 | Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic, Hettangian) | Had a distinctive cross-shaped astragalus | ||

| Shingopana | 2017 | Galula Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian to Maastrichtian) | Most closely related to South American titanosaurs | ||

| Spicomellus | 2021 | El Mers Group (Middle Jurassic, Bathonian to Callovian) | The oldest ankylosaur known and the first one from Africa. Uniquely, its osteoderms were fused directly to its ribs |

| |

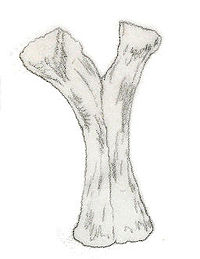

| Spinophorosaurus | 2009 | Irhazer Shale (Middle Jurassic, Bajocian to Bathonian) | Originally described as possessing a "thagomizer" similar to those of stegosaurs,[36] but these turned out to be misidentified clavicles.[37] A high browser with tall shoulders and an elevated neck[38] |

| |

| Spinosaurus | 1915 | Bahariya Formation, Chenini Formation, Kem Kem Group (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Possessed a myriad of features that have been suggested to be evidence of a semiaquatic lifestyle, including webbed feet[39] and a paddle-like tail.[40] However, it is debated if it was a marine piscivore[41] or a shoreline generalist[42] |

| |

| Spinostropheus | 2004 | Tiourarén Formation (Middle Jurassic to Late Jurassic, Bathonian to Oxfordian) | Although often considered a close relative of Elaphrosaurus, these inferences are based on a specimen that cannot actually be referred to this genus[43] |

| |

| Suchomimus | 1998 | Elrhaz Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian to Albian) | Similar to Baryonyx but with a low sail on its back |

| |

| Tataouinea | 2013 | Aïn el Guettar Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Its bones were extensively pneumatized, supporting the theory that sauropods had bird-like respiratory systems | ||

| Tazoudasaurus | 2004 | Azilal Formation (Early Jurassic, Toarcian) | One of the few Early Jurassic sauropods known from reasonably complete remains |

| |

| Tendaguria | 2000 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian) | The first definitive turiasaur known from Africa[7] |

| |

| Thyreosaurus | 2024 | El Mers Group (Middle Jurassic, Bathonian to Callovian?) | May have possessed a recumbent dermal armor, an unusual feature among stegosaurs[44] |

| |

| Tornieria | 1911 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | Has been assigned to different genera throughout its history |

| |

| Veterupristisaurus | 2011 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) | Known from a few vertebrae somewhat similar to those of Acrocanthosaurus |

| |

| Vulcanodon | 1972 | Forest Sandstone (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian to Pliensbachian) | Theropod teeth were found associated with the holotype |

| |

| Wamweracaudia | 2019 | Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic, Tithonian) | The first definitive mamenchisaurid known from outside Asia |

Invalid and potentially valid genera

[edit]- Aetonyx palustris: A potential junior synonym of Massospondylus.

- Fabrosaurus australis: Sometimes considered to be part of a family of small ornithischians called fabrosaurids. It may potentially be a synonym of Lesothosaurus.

- Gigantoscelus molengraafi: Probably a synonym of Euskelosaurus, but this cannot be confirmed.

- Gyposaurus: The African species, G. capensis, may be a juvenile Massospondylus. A Chinese species has also been named, but it may not belong to this genus.

- Hortalotarsus skirtopodus: A possible synonym of Massospondylus.

- "Likhoelesaurus": Suggested to be a giant, early carnosaur but might actually be a pseudosuchian.

- Megapnosaurus: The African species, M. rhodesiensis, might belong to the genus Coelophysis. Another referred species, M. kayentakatae, probably needs its own genus name, as the current one, "Syntarsus", is preoccupied by an insect.

- Nyasasaurus parringtoni: Described in 2013 as the oldest known dinosaur, dating back to the Anisian, but both this date and its classification have been questioned.

- Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis: A spinosaurid contemporary with Spinosaurus. Its status as a distinct genus and/or species is uncertain.

- Torvosaurus: Teeth originally named as Megalosaurus ingens have been reassigned to this genus, but not as a distinct species.

Timeline

[edit]This is a timeline of selected dinosaurs from the list above. Time is measured in mya along the x-axis.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weishampel, D.B.; Witmer, L.M. (1990). "Heterodontosauridae". In Osmólska, H.; Dodson, P.; Weishampel, W.B. (eds.). The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 486–497. ISBN 978-0-520-06726-4. OCLC 20670312.

- ^ Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Raven, Thomas J.; Ouarhache, Driss; Barrett, Paul M. (2020). "North Africa's first stegosaur: Implications for Gondwanan thyreophoran dinosaur diversity". Gondwana Research. 77: 82–97. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2019.07.007. hdl:10141/622706. ISSN 1342-937X.

- ^ Sereno, P. (2017). "Early Cretaceous ornithomimosaurs (Dinosauria: Coelurosauria) from Africa". Ameghiniana. 54 (5): 576–616. doi:10.5710/AMGH.23.10.2017.3155. S2CID 134718338.

- ^ Cerroni, M.A.; Agnolin, F.L.; Brissón Egli, F.; Novas, F.E. (2019). "The phylogenetic position of Afromimus tenerensis Sereno, 2017 and its paleobiogeographical implications". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 159: 103572. Bibcode:2019JAfES.15903572C. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2019.103572. S2CID 201352476.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas R.; Suberbiola, Xabier Pereda; Pyron, R. Alexander; Jalil, Nour-Eddine (2020). "The first duckbill dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Africa and the role of oceanic dispersal in dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research. 120: 104678. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104678. S2CID 228807024.

- ^ Don Lessem; Donald F. Glut (1993). The Dinosaur Society's dinosaur encyclopedia. Tracy Ford (illus.) ... [et al.] ; scientific advisors, Peter Dodson (1st. ed.). New York: Random House. p. 16. ISBN 0-679-41770-2.

- ^ a b c Mannion, P. D.; Upchurch, P.; Schwarz, D.; Wings, O. (2019). "Taxonomic affinities of the putative titanosaurs from the Late Jurassic Tendaguru Formation of Tanzania: phylogenetic and biogeographic implications for eusauropod dinosaur evolution". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 185 (3): 784–909. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zly068. hdl:10044/1/64080.

- ^ a b Mcphee, Blair W.; Bordy, Emese M.; Sciscio, Lara; Choiniere, Jonah N. (2017). "The sauropodomorph biostratigraphy of the Elliot Formation of southern Africa: Tracking the evolution of Sauropodomorpha across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 62 (3): 441–465. doi:10.4202/app.00377.2017.

- ^ Lacerda, Mauro B.S.; Grillo, Orlando N.; Romano, Pedro S.R. (2021). "Rostral morphology of Spinosauridae (Theropoda, Megalosauroidea): Premaxilla shape variation and a new phylogenetic inference". Historical Biology. 34 (11): 2089–2109. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.2000974. S2CID 244418803.

- ^ Sereno Dutheil; Iarochene Larsson; Lyon Magwene; Sidor Varricchio; Wilson (1996). "Predatory Dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous Faunal Differentiation" (PDF). Science. 272 (5264): 986–991. Bibcode:1996Sci...272..986S. doi:10.1126/science.272.5264.986. PMID 8662584. S2CID 39658297.

- ^ Sebastián Apesteguía; Nathan D. Smith; Rubén Juárez Valieri; Peter J. Makovicky (2016). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157793A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157793. PMC 4943716. PMID 27410683.

- ^ Matías J. Motta; Alexis M. Aranciaga Rolando; Sebastián Rozadilla; Federico E. Agnolín; Nicolás R. Chimento; Federico Brissón Egli & Fernando E. Novas (2016). "New theropod fauna from the Upper Cretaceous (Huincul Formation) of northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 71: 231–253.

- ^ a b Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Varricchio, David J.; Martill, David M.; Dutheil, Didier B.; Unwin, David M.; Baidder, Lahssen; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Zouhri, Samir; Kaoukaya, Abdelhadi (2020-04-21). "Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco". ZooKeys (928): 1–216. doi:10.3897/zookeys.928.47517. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 7188693. PMID 32362741.

- ^ Hübner, T.R. (2012). Laudet, V. (ed.). "Bone histology in Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki (Ornithischia: Iguanodontia)--variation, growth, and implications". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e29958. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...729958H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029958. PMC 3253128. PMID 22238683.

- ^ Hübner, T.R.; Rauhut, O.W.M. (2010). "A juvenile skull of Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki (Ornithischia: Iguanodontia), and implications for cranial ontogeny, phylogeny, and taxonomy in ornithopod dinosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 160 (2): 366–396. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00620.x.

- ^ Witzmann, F.; Claeson, K.M.; Hampe, O.; Wieder, F.; Hilger, A.; Manke, I.; Niederhagen, M.; Rothschild, B.M.; Asbach, P. (2011). "Paget disease of bone in a Jurassic dinosaur". Current Biology. 21 (17): R647–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.006. PMID 21920291.

- ^ Taylor, M.P. (2009). "A Re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropod) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensch 1914)" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 787–806. doi:10.1671/039.029.0309. S2CID 15220647.

- ^ Yates, A. M.; Bonnan, M. F.; Neveling, J.; Chinsamy, A.; Blackbeard, M. G. (2010). "A new transitional sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and the evolution of sauropod feeding and quadrupedalism". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1682): 787–794. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1440. PMC 2842739. PMID 19906674.

- ^ Daniela Schwarz; Philip Mannion; Oliver Wings; Christian Meyer (2020). "Re-description of the sauropod dinosaur Amanzia ("Ornithopsis/Cetiosauriscus") greppini n. gen. and other vertebrate remains from the Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) Reuchenette Formation of Moutier, Switzerland". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 113. doi:10.1186/s00015-020-00355-5.

- ^ Mo, Jinyou; Ma, Feimin; Yu, Yilun; Xu, Xing (2022-12-09). "A New Titanosauriform Sauropod with An Unusual Tail from the Lower Cretaceous of Northeastern China". Cretaceous Research. 144: 105449. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105449. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 254524890.

- ^ Ruiz-Omeñaca, José Ignacio; Pereda Suberbiola, Xavier; Galton, Peter M. (2007). "Callovosaurus leedsi, the earliest dryosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia: Euornithopoda) from the Middle Jurassic of England". In Carpenter Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3.

- ^ Dieudonné, P.-E.; Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Godefroit, P.; Tortosa, T. (2020-07-20). "A new phylogeny of cerapodan dinosaurs" (PDF). Historical Biology. 33 (10): 2335–2355. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1793979. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 221854017.

- ^ Rozadilla, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico Lisandro; Novas, Fernando Emilio (2019-12-17). "Osteology of the Patagonian ornithopod Talenkauen santacrucensis (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (24): 2043–2089. doi:10.1080/14772019.2019.1582562. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 155344014.

- ^ Carrano, Matthew T.; Roger B. J. Benson; Scott D. Sampson (2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927. S2CID 85354215.

- ^ McPhee, Blair W.; Benson, Roger B.J.; Botha-Brink, Jennifer; Bordy, Emese M. & Choiniere, Jonah N. (2018). "A giant dinosaur from the earliest Jurassic of South Africa and the transition to quadrupedality in early sauropodomorphs". Current Biology. 28 (19): 3143–3151.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.063. PMID 30270189.

- ^ Sciscio, Lara; Knoll, Fabien; Bordy, Emese M.; Kock, Michiel O. de; Redelstorff, Ragna (2017-03-01). "Digital reconstruction of the mandible of an adult Lesothosaurus diagnosticus with insight into the tooth replacement process and diet". PeerJ. 5: e3054. doi:10.7717/peerj.3054. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5335715. PMID 28265518.

- ^ T. R., Holtz Jr.; Rey, L. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ Carballido, J.L.; Otero, A.; Mannion, P.D.; Salgado, L.; Moreno, A.P. (2022). "Titanosauria: A Critical Reappraisal of Its Systematics and the Relevance of the South American Record". In Otero, A.; Carballido, J.L.; Pol, D. (eds.). South American Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Record, Diversity and Evolution. Springer. pp. 269–298. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95959-3. ISBN 978-3-030-95958-6. ISSN 2197-9596. S2CID 248368302.

- ^ Sallam, H.; Gorscak, E.; O'Connor, P.; El-Dawoudi, I.; El-Sayed, S.; Saber, S. (2017-06-26). "New Egyptian sauropod reveals Late Cretaceous dinosaur dispersal between Europe and Africa". Nature. 2 (3): 445–451. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0455-5. PMID 29379183. S2CID 3375335.

- ^ Griffin, Christopher T.; Wynd, Brenen M.; Munyikwa, Darlington; Broderick, Tim J.; Zondo, Michel; Tolan, Stephen; Langer, Max C.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Taruvinga, Hazel R. (2022-08-31). "Africa's oldest dinosaurs reveal early suppression of dinosaur distribution". Nature. 609 (7926): 313–319. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05133-x. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 36045297. S2CID 251977824.

- ^ Buffetaut, Eric (2012). "An early spinosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) and the evolution of the spinosaurid dentition" (PDF). Oryctos. 10: 1–8.

- ^ Soto, Matías; Toriño, Pablo; Perea, Daniel (2020-11-01). "Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Ceratosauria) teeth from the Tacuarembó Formation (Late Jurassic, Uruguay)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 103: 102781. Bibcode:2020JSAES.10302781S. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102781. ISSN 0895-9811. S2CID 224842133.

- ^ Sereno, Paul C.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Conrad, Jack L. (2004-07-07). "New dinosaurs link southern landmasses in the Mid-Cretaceous". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1546): 1325–1330. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2692. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1691741. PMID 15306329.

- ^ Delcourt, Rafael (2018). "Ceratosaur palaeobiology: new insights on evolution and ecology of the southern rulers". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 9730. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.9730D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28154-x. PMC 6021374. PMID 29950661.

- ^ Paterna A, Cau A (2022). "New giant theropod material from the Kem Kem Compound Assemblage (Morocco) with implications on the diversity of the mid-Cretaceous carcharodontosaurids from North Africa". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology: 1–9. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2131406. S2CID 252856791.

- ^ Remes, K.; Ortega, F.; Fierro, I.; Joger, U.; Kosma, R.; Marín Ferrer, J. M.; Ide, O. A.u; Maga, A.; Farke, A. A. (2009). "A new basal sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Niger and the early evolution of Sauropoda". PLOS ONE. 4 (9): e6924. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6924R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006924. PMC 2737122. PMID 19756139.

- ^ Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O. (2013). "Clavicles, interclavicles, gastralia, and sternal ribs in sauropod dinosaurs: new reports from Diplodocidae and their morphological, functional and evolutionary implications". Journal of Anatomy. 222 (3): 321–340. doi:10.1111/joa.12012. PMC 3582252. PMID 23190365.

- ^ Vidal, D.; Mocho, P.; Aberasturi, A.; Sanz, J. L.; Ortega, F. (2020). "High browsing skeletal adaptations in Spinophorosaurus reveal an evolutionary innovation in sauropod dinosaurs". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 6638. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.6638V. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-63439-0. PMC 7171156. PMID 32313018. S2CID 215819745.

- ^ Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Fabri, Matteo; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Myhrvold, Nathan; Lurino, Dawid A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–6. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. S2CID 34421257. Supplementary Information

- ^ Ibrahim, Nizar; Maganuco, Simone; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Fabbri, Matteo; Auditore, Marco; Bindellini, Gabriele; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Mattarelli, Diego A.; Unwin, David M.; Wiemann, Jasmina (2020). "Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur". Nature. 581 (7806): 67–70. Bibcode:2020Natur.581...67I. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2190-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32376955. S2CID 216650535.

- ^ Fabbri, Matteo; Navalón, Guillermo; Benson, Roger B. J.; Pol, Diego; O'Connor, Jingmai; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Norell, Mark A.; Orkney, Andrew; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Zouhri, Samir; Becker, Justine; Emke, Amanda; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Bindellini, Gabriele; Maganuco, Simone; Auditore, Marco; Ibrahim, Nizar (March 23, 2022). "Subaqueous foraging among carnivorous dinosaurs". Nature. 603 (7903): 852–857. Bibcode:2022Natur.603..852F. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04528-0. PMID 35322229. S2CID 247630374.

- ^ Sereno, Paul C.; Myhrvold, Nathan; Henderson, Donald M.; Fish, Frank E.; Vidal, Daniel; Baumgart, Stephanie L.; Keillor, Tyler M.; Formoso, Kiersten K.; Conroy, Lauren L. (2022). "Spinosaurus is not an aquatic dinosaur". eLife. 11. e80092. doi:10.7554/eLife.80092. PMC 9711522. PMID 36448670.

- ^ Rauhut, O.W.M., and Carrano, M.T. (2016). The theropod dinosaur Elaphrosaurus bambergi Janensch, 1920, from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, (advance online publication) doi:10.1111/zoj.12425

- ^ Zafaty, O.; Oukassou, M.; Riguetti, F.; Company, J.; Bendrioua, S.; Tabuce, R.; Charrière, A.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (2024). "A new stegosaurian dinosaur (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) with a remarkable dermal armour from the Middle Jurassic of North Africa". Gondwana Research. 131: 344–362. Bibcode:2024GondR.131..344Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2024.03.009.