Death poem

A death poem (絶命詩) is a poem written near the time of one's own death. It is a tradition for literate people to write one in a number of different cultures, especially in Joseon Korea and Japan with the jisei no ku (辞世の句).

Japanese death poems

History

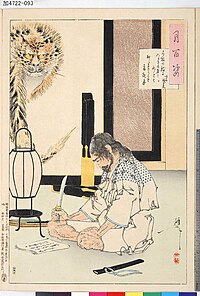

Death poems have been written by Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Zen monks (the latter writing kanshi (Japanese poetry composed in Chinese), waka or haiku), and by many haiku poets. It was an ancient custom in Japan for literate persons to compose a jisei on their deathbed. One of earliest records of jisei was recited by Prince Ōtsu executed in 686. For examples of death poems, see the articles on the famous haiku poet Bashō, the Japanese Buddhist monk Ryōkan, Ōta Dōkan (builder of Edo Castle), the monk Gesshū Sōko, and the Japanese woodblock master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. The custom has continued into modern Japan.

On March 17, 1945, General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese commander-in chief during the Battle of Iwo Jima, sent a final letter to Imperial Headquarters. In the message, General Kuribayashi had apologized for failing to successfully defend Iwo Jima against the overwhelming forces of the United States Military. At the same time, however, he had expressed great pride in the heroism of his men, who, starving and thirsty, had been reduced to fighting with rifle butts and fists. He closed the message with a traditional death poem.

- Sadness overcomes me as I am unable to fulfill my duty for my country,

- Bullets and arrows are no more

- I, falling in the field without revenge,

- Will be reborn to take up my sword again.

- When ugly weeds run riot over this island,

- My heart and soul will be with the fate of the Imperial nation.[1]

Some people left their jisei in multiple forms. Prince Ōtsu made both waka and kanshi, Sen no Rikyū made both kanshi and kyōka.

A death poem sometimes took on an aspect of a will, reconciling differences between persons[citation needed].

Content

Poetry has long been a core part of Japanese tradition. Death poems are typically graceful, natural, and emotionally neutral, in accordance with the teachings of Buddhism and Shinto. Excepting the earliest works of this tradition, it has been considered inappropriate to mention death explicitly; rather, metaphorical references such as sunsets, autumn or falling cherry blossom suggest the transience of life.

As a once-in-a-lifetime event, it was common to converse with respected poets before, and sometimes well in advance of a death, to help finish writing a poem[citation needed]. As the time passed, the poem might be rewritten, but this rewriting was almost never mentioned, to keep from tarnishing the deceased person's legacy[citation needed].

Seppuku

In a full ceremonial seppuku (Japanese ritual suicide) one of the elements of the ritual is the writing of a death poem. The poem is written in the tanka style (five units, usually composed of five, seven, five, seven, and seven moras respectively).

In 1970 writer Yukio Mishima and his disciples composed jisei before their abortive takeover of the Ichigaya garrison in Tokyo, where they killed themselves in this ritual manner.[2]

Korean death poems

Besides Korean Buddhist monks, Confucian scholars called seonbis sometimes wrote death poems (절명시). However, better known examples are those written or recited by famous historical figures facing death when they were executed for loyalty to their former king or due to insidious plot. They are therefore impromptu verses, often declaring their loyalty or steadfastness. The following are some examples that are still learned by school children in Korea as models of loyalty. These examples are wrriten in Korean sijo (three lines of 3-4-3-4 or its variation) or in Hanja five-syllable format (5-5-5-5 for a total of 20 syllables) of ancient Chinese poetry (五言詩).

Yi Gae

Yi Gae (이개·1417-1456) was one of "six martyred ministers" who were executed for conspiring to assassinate King Sejo after Sejo usurped the throne from his nephew Danjong. Sejo offered to pardon six ministers including Yi Gae and Seong Sam-mun if they would repent their crime and accept his legitimacy, but Yi Gae and all others refused. He recited the following poem in his cell before execution on June 8, 1456. In this sijo, Lord (임) actually should read someone beloved or cherised, meaning King Danjong in this instance.[3]

방안에 혔는 촛불 눌과 이별하엿관대

겉으로 눈물지고 속타는 줄 모르는다.

우리도 천리에 임 이별하고 속타는 듯하여라.

Oh, candlelight shining the room, with whom did you part?

You shed tears without and burn within, yet no one notices.

We part with our Lord on a long journey and burn like thee.

Seong Sam-mun

Like Yi Gae, Seong Sam-mun (성삼문·1418–1456) was one of "six marytred ministers" and was the leader of conspiracy to assassinate Sejo. Like Yi Gae, he refused the offer of pardon and denied Sejo's legitimacy. He recited the following sijo in prison and the second one (five-syllable poem) on his way to the place of execution, where his limbs were tied to oxen and torn apart. [4]

이 몸이 주거 가서 무어시 될고 하니,

봉래산(蓬萊山) 제일봉(第一峯)에 낙락장송(落落長松) 되야 이셔,

백설(白雪)이 만건곤(滿乾坤)할 제 독야청청(獨也靑靑) 하리라.

What shall I become when this body is dead and gone?

A tall, thick pine tree on the highest peak of Bongraesan,

Evergreen alone when white snow covers the whole world.

擊鼓催人命 (격고최인명) -둥둥 북소리는 내 생명을 재촉하고,

西風日欲斜 (회두 일욕사) -머리를 돌여 보니 해는 서산으로 넘어 가려고 하는구나

黃泉無客店 (황천무객점) -황천으로 가는 길에는 주막조차 없다는데,

今夜宿誰家 (금야숙수가) -오늘밤은 뉘 집에서 잠을 자고 갈거나

As the sound of drum calls for my life,

I turn my head where sun is about to set.

There is no inn on the way to underworld.

At whose house shall I sleep tonight?

Jo Gwang-jo

Jo Gwang-jo (조광조·1482-1519) was a neo-Confucian reformer who was framed by the conservative faction opposing his reforms in the Third Literati Purge of 1519. His political enemies slandered Jo to be disloyal by writing "Jo will become the king" (주초위왕, 走肖爲王) with honey on leaves so that caterpillars left behind the same phrase as if in supernatural manifestation. King Jungjong ordered his death by sending poison and abandoned Jo's reform measures. Jo, who had believed to the end that Jungjong would see his errors, wrote the following before drinking poison on December 20, 1519. [5] Repetition of similar looking words is used to emphasize strong conviction in this five-syllable poem.

愛君如愛父 (애군여애부) 임금 사랑하기를 아버지 사랑하듯 하였고

憂國如憂家 (우국여우가) 나라 걱정하기를 집안 근심처럼 하였다

白日臨下土 (백일임하토) 밝은 해 아래 세상을 굽어보사

昭昭照丹衷 (소소조단충) 내 단심과 충정 밝디 밝게 비춰주소서

Loved my sovereign as own father

Worried over country as own house

The bright sun looking down upon earth

Shines ever so brightly on my red heart.

Jeong Mong-ju

Jeong Mong-ju (정몽주·1337-1392), considered "father" of Korean neo-Confucianism, was a high minister of Goryeo dynasty when Yi Seong-gye overthrew Goryeo and established Joseon dynasty. He answered with the following sijo to the future Taejong of Joseon when the latter demanded his support for the new dynasty with a poem of his own. Just as he suspected, he was assassinated the same night on April 4, 1392.

이몸이 죽고 죽어 일백 번 고쳐 죽어

백골이 진토되어 넋이라도 있고 없고

임 향한 일편 단심이야 가실 줄이 있으랴.

Should this body die and die again a hundred times over,

White bones turning to dust, with or without trace of soul,

My steadfast heart toward Lord, could it ever fade away?

See also

Notes

- ^ Tadamichi Kuribayashi, Picture Letters from the Commander in Chief, page 233.

- ^ Donald Keene, The Pleasures of Japanese Literature, p.62

- ^ Korean Sijo Literature Association [1]

- ^ Kim Cheon-tak, Cheong-gu-yeong-un, 1728

- ^ Annals of Joseon Dynasty, December 16, 1519

References

- Blackman, Sushila (1997). Graceful Exits: How Great Beings Die: Death Stories of Tibetan, Hindu & Zen Masters. Weatherhill, Inc.: USA, New York, New York. ISBN 0-8348-0391-7

- Hoffmann, Yoel (1986). Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death. Charles E. Tuttle Company: USA, Rutland, Vermont. ISBN 0-8048-1505-4