Dark matter halo

A dark matter halo is a hypothetical component of a galaxy that envelops the galactic disc and extends well beyond the edge of the visible galaxy. The halo's mass dominates the total mass. Since they consist of dark matter, halos cannot be observed directly, but their existence is inferred through their effects on the motions of stars and gas in galaxies. Dark matter halos play a key role in current models of galaxy formation and evolution.

Rotation curves as evidence of a dark matter halo

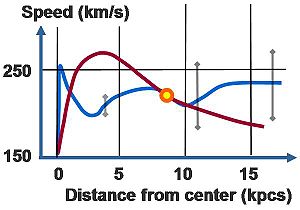

The presence of dark matter in the halo is inferred from its gravitational effect on a spiral galaxy's rotation curve. Without large amounts of mass throughout the (roughly spherical) halo, the rotational velocity of the galaxy would decrease at large distances from the galactic center, just as the orbital speeds of the outer planets decrease with distance from the Sun. However, observations of spiral galaxies, particularly radio observations of line emission from neutral atomic hydrogen (known, in astronomical parlance, as HI), show that the rotation curve of most spiral galaxies flattens out, meaning that rotational velocities do not decrease with distance from the galactic center. The absence of any visible matter to account for these observations implies either that unobserved ("dark") matter exists or that the theory of motion under gravity (General Relativity) is incomplete.

A commonly used model for galactic dark matter halos is the pseudo-isothermal halo

This provides a good fit to most rotation curve data. However, it cannot be a complete description, as the enclosed mass fails to converge to a finite value as the radius tends to infinity. Though empirically successful, it has no basis in deeper theory.

Numerical simulations of structure formation in an expanding universe lead to the theoretical prediction of the NFW (Navarro-Frenk-White) profile:[4]

this profile has a finite gravitational potential even though the integrated mass still diverges logarithmically. It has become conventional to refer to the mass of a halo at a fiducial point that encloses an overdensity 200 times greater than the critical density of the universe, though mathematically the profile extends beyond this notional point. NFW halos generally provide a worse description of galaxy data than does the pseudo-isothermal profile, leading to the cuspy halo problem.

Higher resolution computer simulations are better described by the Einasto profile:[5]

While the addition of a third parameter provides a slightly improved description of the results from numerical simulations, it is not observationally distinguishable from the 2 parameter NFW halo,[6] and does nothing to alleviate the cuspy halo problem.

Theories about the nature of dark matter

The nature of dark matter in the galactic halo of spiral galaxies is still undetermined, but there are two popular theories: either the halo is composed of weakly interacting elementary particles known as WIMPs, or it is home to large numbers of small, dark bodies known as MACHOs. It seems unlikely that the halo is composed of large quantities of gas and dust, because both ought to be detectable through observations. Searches for gravitational microlensing events in the halo of the Milky Way show that the number of MACHOs is likely not sufficient to account for the required mass.

Milky Way dark matter halo

The visible disk of the Milky Way Galaxy is embedded in a much larger, roughly spherical halo of dark matter. The dark matter density drops off with distance from the galactic center. It is now believed that about 95% of the Galaxy is composed of dark matter, a type of matter that does not seem to interact with the rest of the Galaxy's matter and energy in any way except through gravity. The luminous matter makes up approximately 9 x 1010 solar masses. The dark matter halo is likely to include around 6 x 1011 to 3 x 1012 solar masses of dark matter.[7][8]

See also

- Galaxy formation and evolution

- Galactic coordinate system

- Disc (galaxy)

- Bulge (astronomy)

- Galactic halo

- Spiral arm

- Dark matter

- Dark galaxy

- Universal Rotation Curve

References

- ^ Peter Schneider (2006). Extragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology. Springer. p. 4, Figure 1.4. ISBN 3-540-33174-3.

- ^ Theo Koupelis, Karl F Kuhn (2007). In Quest of the Universe. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 492; Figure 16-13. ISBN 0-7637-4387-9.

- ^ Mark H. Jones, Robert J. Lambourne, David John Adams (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 21; Figure 1.13. ISBN 0-521-54623-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Navarro, J. et al. (1997), A Universal Density Profile from Hierarchical Clustering

- ^ Merritt, D. et al. (2006), Empirical Models for Dark Matter Halos. I. Nonparametric Construction of Density Profiles and Comparison with Parametric Models

- ^ McGaugh, S. "et al." (2007), The Rotation Velocity Attributable to Dark Matter at Intermediate Radii in Disk Galaxies

- ^ Battaglia et al. (2005), The radial velocity dispersion profile of the Galactic halo: constraining the density profile of the dark halo of the Milky Way

- ^ Kafle, P.R.; Sharma, S.; Lewis, G.F.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. (2014). "On the Shoulders of Giants: Properties of the Stellar Halo and the Milky Way Mass Distribution". The Astrophysical Journal. 794 (1): 17. arXiv:1408.1787. Bibcode:2014ApJ...794...59K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/794/1/59.

Further reading

- Bertone, Gianfranco (2010). Particle Dark Matter: Observations, Models and Searches. Cambridge University Press. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-521-76368-4.

- Brainerd, Tereasa (July 2011). "How are Bright Galaxies Embedded within their Dark Matter Halos?". Astronomical Review. 6 (7). Retrieved 11 October 2012.

![{\displaystyle \rho (r)={\frac {\rm {constant}}{[1+(r/a)^{2}]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d2d51ab6513bc5922a02cce5e09cc2b2410317bd)