Dakosaurus

| Dakosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

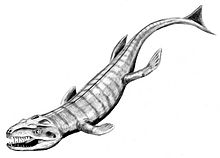

| Dakosaurus maximus leaping after two pterosaurs | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Dakosaurus |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

Dakosaurus is an extinct genus within the family Metriorhynchidae that lived during the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. It was large, with teeth that were serrated and compressed lateromedially (flattened from side to side). The genus was established by Friedrich August von Quenstedt in 1856 for an isolated tooth named Geosaurus maximus by Plieninger. Dakosaurus was a carnivore that spent much, if not all, its life out at sea. The extent of its adaptation to a marine lifestyle means that it is most likely that it mated at sea, but since no eggs or nests have been discovered that have been referred to Dakosaurus, whether it gave birth to live young at sea like dolphins and ichthyosaurs or came ashore like turtles is not known. The name Dakosaurus means "tearing lizard", and is derived from the Greek Dakos- ("to tear") and Template:Polytonic -sauros ("lizard").

Discovery and species

When isolated Dakosaurus teeth were first discovered in Germany, they were mistaken for belonging to the theropod dinosaur Megalosaurus.[8]

Fossil specimens referrable to Dakosaurus are known from Late Jurassic deposits from England, France, Switzerland, Germany,[9] Poland,[10] Russia,[11] Argentina,[3] and Mexico.[12] Teeth referrable to Dakosaurus are known from Europe from the Oxfordian to the Valanginian.[13][14]

Valid species

The type species Dakosaurus maximus, meaning "greatest tearing lizard" is known from fossil discoveries in Western Europe (England, France, Switzerland and Germany) of the Late Jurassic (Late Kimmeridgian-Early Tithonian).[9][15]

Dakosaurus andiniensis, meaning "tearing lizard from the Andes", was first discovered in 1987 in the Neuquén Basin, a very rich fossil bed in Argentina. However, it was not until 1996 that the binomen Dakosaurus andiniensis was erected.[3] Two recently discovered skulls have indicated that D. andiniensis is unique among the metriorhynchids (the most specialised family of crocodylians to marine life) with its short, tall snout (which is why it was nicknamed Godzilla).This species has a fossil range from the End Jurassic-Beginning Cretaceous (Late Tithonian-Early Berriasian).[16]

Dakosaurus lapparenti, meaning "Lapparent's tearing lizard", was named in honour of French palaeontologist Albert-Félix de Lapparent. It is based upon isolated skull and post-cranial bones from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) of France.[4]

Dakosaurus carpenteri, meaning "Carpenter's tearing lizard" is known from fossils from England of the Late Jurassic (late Kimmeridgian).[5]

Unnamed species

Incomplete skull specimens of Dakosaurus has been discovered in Kimmeridgian age rocks from Mexico.[12][17]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The genus Plesiosuchus is a junior synonym of Dakosaurus,[7] while Dacosaurus is a mis-spelling.[6] Recent phylogenetic analysis however, does not support the monophyly of Dakosaurus,[18] although the species D. maximus and D. andiniensis do constite a natural group.[5][16][18]

Palaeobiology

Morphology

All currently known species would have been approximately four to five metres in length, which when compared to living crocodilians, Dakosaurus can be considered large-sized. Its body was streamlined for greater hydrodynamic efficiency, which along with its finned tail made it a more efficient swimmer than modern crocodilian species.[19]

Salt glands

The incomplete skull specimens from the Mexican species of Dakosaurus preserves the chamber in which the well-developed salt glands (known from Geosaurus[20] and Metriorhynchus[21]) would have been housed. Unfortunately, there was no preservational evidence of the glands themselves.[12]

Niche partitioning

Dakosaurus maximus is one of several species of metriorhynchids known from the Mörnsheim Formation (Solnhofen limestone, early Tithonian) of Bavaria, Germany. Alongside three species of Geosaurus, it has been hypothesised that niche partitioning enabled several species of crocodyliforms to co-exist. Dakosaurus and Geosaurus giganteus would have been top predators of this Formation, both of which were large, short-snouted species with serrated teeth. The remaining two species of Geosaurus, and the teleosaurid Steneosaurus would have feed mostly on fish.[22]

From the slightly older Nusplingen Plattenkalk (late Kimmeridgian) of southern Germany, both D. maximus and Geosaurus suevicus are contemporaneous. As with Solnhofen, Dakosaurus was the top predator, while G. suevicus was a fish-eater.[23]

Diet

Dakosaurus was the only marine crocodyliform to have evolved teeth both lateromedially compressed and serrated; not only that, but they were much larger than those of metriorhynchid genera.[16] These characteristics, along with their morphology falling into the 'Cut' guild of Massare (1987) - which are analogous to modern killer whale teeth - are indicative of Dakosaurus being an apex predator.[24]

The enlarged supratemporal fenestrae of Dakosaurus skulls[15] would have anchored large adductor muscles (jaw closing),[25] ensuring a powerful bite. As their skulls are triangular in shape, with deeply rooted large, serrated teeth and a bulbous, deep mandibular symphysis (like pliosaurs), dakosaurs would also have been able to twist feed (tear chunks of flesh of potential prey).[26]

See also

References

- ^ a b Quenstedt FA. 1856. Sonst und Jetzt: Populäre Vortäge über Geologie. Tübingen: Laupp, 131.

- ^ Plieninger T. 1846. Prof. Dr. Th. Plieninger hielt nachstehenden vortrag über ein neues Sauriergenus und die Einreihung der Saurier mit flachen, schneidenden Zähnen in eine Familie. Pp. 148-154 in: Zweite Generalversammlung am 1. Mai 1846 zu Tübingen. Württembergische naturwissenschaftliche Jahreshefte 2: 129-183.

- ^ a b c Vignaud P, Gasparini ZB. 1996. New Dakosaurus (Crocodylomorpha, Thalattosuchia) from the Upper Jurassic of Argentina. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Paris, 2 322: 245-250.

- ^ a b Debelmas J, Strannoloubsky A. 1957. Découverte d’un crocodilien dans le Néocomien de La Martre (Var) Dacosaurus lapparenti n. sp. Travaux Laboratoire de Géologie de l’université de Grenoble 33: 89-99.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson LE, Young MT, Benton MJ. 2008. A new metriorhynchid crocodilian (Mesoeucrocodylia: Thalattosuchia) from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of Wiltshire, UK. Palaeontology 51 (6): 1307-1333.

- ^ a b Sauvage HE. 1873. Notes sur les reptiles, fossiles. Bulletin de la Société Géologiques de France, série 3: 365-384.

- ^ a b Owen R. 1884. On the cranial and vertebral characters of the crocodilian genus Plesiosuchus, Owen. Quarterly Journal of Geological Society London 40: 153-159.

- ^ Quenstedt FA. 1843. Das Flötzgebirge Württembergs: mit besonderer rücksicht auf den Jura. Tübingen: Laupp, 493.

- ^ a b Steel R. 1973. Crocodylia. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie, Teil 16. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag,116 pp.

- ^ Radwańska U, Radwański A. 2003. The Jurassic crinoid genus Cyclocrinus D’Orbigny, 1850: still an enigma. Acta Geologica Polonica 53 (2003),(4): 301-320.

- ^ Ochev VG. 1981. [Marine crocodiles in the Mesozoic of Povolzh'e] Priroda 1981: 103

- ^ a b c Buchy M-C, Stinnesbeck W, Frey E, Gonzalez AHG. 2007. First occurrence of the genus Dakosaurus (Crocodyliformes, Thalattosuchia) in the Late Jurassic of Mexico. Bulletin de la Societe Geologique de France 178 (5): 391-397.

- ^ BM(NH), Trustees of the. 1983. British Mesozoic Fossils, sixth edition. London: Butler & Tanner Ltd, 209 pp.

- ^ Benton MJ, Spencer PS. 1995. Fossil Reptiles of Great Britain. London: Chapman and Hall, 386 pp.

- ^ a b Fraas E. 1902. Die Meer-Krocodilier (Thalattosuchia) des oberen Jura unter specieller Berücksichtigung von Dacosaurus und Geosaurus. Paleontographica 49: 1-72.

- ^ a b c Gasparini Z, Pol D, Spalletti LA. 2006. An unusual marine crocodyliform from the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary of Patagonia. Science 311: 70-73.

- ^ Buchy M-C. 2008. New occurrence of the genus Dakosaurus (Reptilia, Thalattosuchia) in the Upper Jurassic of north-eastern Mexico with comments upon skull architecture of Dakosaurus and Geosaurus. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 249 (1): 1-8.

- ^ a b Young MT. 2007. The evolution and interrelationships of Metriorhynchidae (Crocodyliformes, Thalattosuchia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (3): 170A.

- ^ Massare JA. 1988. Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles; implications for method of predation. Paleobiology 14 (2):187-205.

- ^ Fernández M, Gasparini Z. 2000. Salt glands in a Tithonian metriorhynchid crocodyliform and their physiological significance. Lethaia 33: 269-276.

- ^ Gandola R, Buffetaut E, Monaghan N, Dyke G. 2006. Salt glands in the fossil crocodile Metriorhynchus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (4): 1009-1010.

- ^ Andrade MB, Young MT. 2008. High diversity of thalattosuchian crocodylians and the niche partition in the Solnhofen Sea. The 56th Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy

- ^ Dietl G, Dietl O, Schweigert G, Hugger R. 2000. Der Nusplinger Plattenkalk (Weißer Jura zeta) - Grabungskampagne 1999.

- ^ Massare JA. 1987. Tooth morphology and prey preference of Mesozoic marine reptiles. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 7: 121-137.

- ^ Holliday CM, Witmer LM. Archosaur adductor chamber evolution: integration of musculoskeletal and topological criteria in jaw muscle homology. Journal of Morphology 268 (6): 457-484.

- ^ Martill DM, Taylor MA, Duff KL, Riding JB, Brown PR. 1994. The trophic structure of the biota of the Peterborough Member, Oxford Clay Formation (Jurassic), UK. Journal of the Geological Society, London 151: 173-194.