Jesus healing the bleeding woman

Jesus healing the bleeding woman (or "woman with an issue of blood" and other variants) is one of the miracles of Jesus recorded in the synoptic gospels.[1][2]

Context

[edit]In the Gospel accounts, this miracle immediately follows the exorcism at Gerasa and is combined with the miracle of the raising of Jairus's daughter. The narrative interrupts the story of Jairus's daughter, a stylistic element which scholars call an intercalated or sandwich narrative.[3][4]

Narrative comparison

[edit]There are several differences between the accounts given by Mark, Matthew and Luke.

Mark

[edit]The incident occurred while Jesus was traveling to Jairus's house, amid a large crowd, according to Mark:

And a woman was there who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years. She had suffered a great deal under the care of many doctors and had spent all she had, yet instead of getting better she grew worse. When she heard about Jesus, she came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak, because she thought, "If I just touch his clothes, I will be healed." Immediately her bleeding stopped and she felt in her body that she was freed from her suffering. At once Jesus realized that power had gone out from him. He turned around in the crowd and asked, "Who touched my clothes?" "You see the people crowding against you," his disciples answered, "and yet you can ask, 'Who touched me?'" But Jesus kept looking around to see who had done it. Then the woman, knowing what had happened to her, came and fell at his feet and, trembling with fear, told him the whole truth. He said to her, "Daughter, your faith has healed you. Go in peace and be freed from your suffering.

— Mark 5:25–34, New International Version[5]

The woman's condition, which is not clear in terms of a modern medical diagnosis, is translated as an 'issue of blood' in the King James Version and a 'flux of blood' in the Wycliffe Bible and some other versions. In scholarly language she is often referred to by the original New Testament Greek term as the haemorrhoissa (ἡ αἱμοῤῥοοῦσα, 'bleeding woman'). The text describes her as gynē haimorroousa dōdeka etē (γυνὴ αἱμορροοῦσα δώδεκα ἔτη), with haimorroousa being a verb in the active voice present participle ("having had a flow [rhēon], of blood [haima]"). Some scholars view it as menorrhagia; others as haemorrhoids.[6]

Because of the continual bleeding, the woman would have been continually regarded in Jewish law as a Zavah or menstruating woman, and so ceremonially unclean. In order to be regarded as clean, the flow of blood would need to stop for at least 7 days. Because of the constant bleeding, this woman lived in a continual state of uncleanness which would have brought upon her social and religious isolation.[7] It would have prevented her from getting married – or, if she was already married when the bleeding started, would have prevented her from having sexual relations with her husband and might have been cited by him as grounds for divorce.

Matthew and Luke

[edit]Matthew's and Luke's accounts specify the "fringe" of his cloak, using a Greek word which also appears in Mark 6.[8] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on fringes in Scripture, the Pharisees (one of the sects of Second Temple Judaism) who were the progenitors of modern Rabbinic Judaism, were in the habit of wearing extra-long fringes or tassels (Matthew 23:5),[9] a reference to the formative ritual fringes (tzitzit). Because of the Pharisees' authority, people regarded the fringe as having a mystical quality.[10]

Matthew's version is much more concise, and shows notable differences and even discrepancies compared to the Markan and Lukan accounts. Matthew does not say the woman failed to find anyone who could heal her (as Luke and Mark do), let alone that she spent all her savings paying physicians but the affliction had only grown worse (as Mark does). There is no crowd in Matthew's account; Jesus immediately notices that the woman touched him instead of having to ask and look amongst the crowd who touched him. Neither is the woman trembling in fear and telling him why she did it. Jesus is not said to feel a loss of power according to Matthew; the woman is only healed after Jesus talks to her, not immediately upon touching his cloak.[11]

Commentary

[edit]Cornelius a Lapide comments on why the woman, after being healed was fearful of Jesus, writing that she had "approached secretly, and, unclean," touching Christ who was clean, and so had, "stolen a gift of healing from Christ without His knowledge." Thus it appears she was concerned that Christ might rebuke her, and potentially recall the benefit, or punish her with a worse disease. From this Lapide concludes "that she had not perfect faith."[12]

Venerable Bede wrote that Christ asked the question, "Who touched My garments?" so that the healing which he had given her, being declared and made known, "might advance in many the virtue of faith, and bring them to believe in Christ."[citation needed]

Given that the woman was cured when she touched the hem of the garment, John McEvilly writes in his Gospel commentary, supports the doctrine of the efficacy of relics, that is, that physical objects can have divine power in them. The same being clear from the miracles produced from contact with the bones of Elisha (2 Kings 13:21),[13] as well as the shadow of Peter curing diseases (Acts 5:15).[14][15]

In art and later traditions

[edit]

Eusebius, writing in the reign of Constantine I, says he himself saw a pair of statues in bronze in Panease or Caesarea Philippi (on the Golan Heights in modern terms) of Jesus and the haemorrhoissa, sculpture being at this time an unusual form for the depiction of Jesus. By his description they resembled a sculptural version of the couple as they were shown in a number of paintings in the Catacombs of Rome. He sees this in terms of ancient traditions of commemorating local notables rather than newer ones of Early Christian art. The statues were placed outside the house of the woman, who came from the city, and was called Veronica (meaning 'true image'), according to the apocrypha Acts of Pilate and later tradition, which gave other details of her life.[16]

When Julian the Apostate became emperor in 361 he instigated a programme to restore Hellenic paganism as the state religion.[17] In Panease this resulted in the replacement of the statue of Christ, with results described by Sozomen, writing in the 440s:

Having heard that at Caesarea Philippi, otherwise called Panease Paneades, a city of Phoenicia, there was a celebrated statue of Christ, which had been erected by a woman whom the Lord had cured of a flow of blood. Julian commanded it to be taken down, and a statue of himself erected in its place; but a violent fire from the heaven fell upon it, and broke off the parts contiguous to the breast; the head and neck were thrown prostrate, and it was transfixed to the ground with the face downwards at the point where the fracture of the bust was; and it has stood in that fashion from that day until now, full of the rust of the lightning.

— Wilson 2004, p. 99

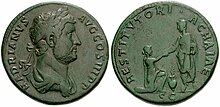

However, it has been pointed out since the 19th century that the statues were probably a misunderstanding or distortion of a sculptural group in fact originally representing the submission of Judea to the Emperor Hadrian. Images of this particular coupling, typical of Roman Imperial adventus imagery, appear on a number of Hadrian's coins, after the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–136. The statues seem to have been buried in a landslide and some time later rediscovered and interpreted as Christian. Since Caesarea Philippi had been celebrated for its temple of the god Pan, a Christian tourist attraction was no doubt welcome news for the city's economy.[18][a]

Representations of the episode which seem clearly to draw on the lost statue, and so resemble surviving coins of the imperial image, appear rather frequently in Early Christian art, with several in the Catacombs of Rome, as illustrated above, on the Brescia Casket and Early Christian sarcophagi, and in mosaic cycles of the Life of Christ such as San Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. It continued to be depicted sometimes until the Gothic period, and then after the Renaissance.[19]

The story was later elaborated in the 11th century in the West by adding that Christ gave her a portrait of himself on a cloth, with which she later cured Tiberius. This Western rival to the Image of Edessa or Mandylion eventually turned into the major Western icon of the Veil of Veronica, now with a different story for "Veronica". The linking of this image with the bearing of the cross in the Passion, and the miraculous appearance of the image was made by Roger d'Argenteuil's Bible in French in the 13th century,[20] and gained further popularity following the internationally popular work, Meditations on the Life of Christ of about 1300 by a Pseudo-Bonaventuran author. It is also at this point that other depictions of the image change to include a crown of thorns, blood, and the expression of a man in pain,[20] and the image became very common throughout Catholic Europe, forming part of the Arma Christi, and with the meeting of Jesus and Veronica becoming one of the Stations of the Cross.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For other possibilities, and possible visual depictions of the statue, see Wilson 2004, pp. 90–97

Citations

[edit]- ^ Matthew 9:20–22, Mark 5:25–34, Luke 8:43–48

- ^ Donahue & Harrington 2005, p. 182.

- ^ Edwards 1989, pp. 193–216.

- ^ Shepherd 1995, pp. 522–540.

- ^ Mark 5:25–34

- ^ "Matthew 9:20 Commentaries: And a woman who had been suffering from a hemorrhage for twelve years, came up behind Him and touched the fringe of His cloak". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ MacArthur 1987, p. 80.

- ^ Strong 1894, p. 43, G2899.

- ^ Matthew 23:5

- ^ Souvay 1909.

- ^ Matthew 9:20–22

- ^ Lapide, Cornelius (1889). The great commentary of Cornelius à Lapide. Translated by Thomas Wimberly Mossman. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 2 Kings 13:21

- ^ Acts 5:15

- ^ MacEvilly, Rev. John (1898). An Exposition of the Gospels. New York: Benziger Brothers.

- ^ Wace 1911, p. 1006.

- ^ Brown 1989, p. 93.

- ^ Schaff & Wace 1890, note 2296.

- ^ Schiller 1971, pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b Schiller 1972, pp. 78–79.

Sources

[edit]- Brown, Peter (1989). The World of Late Antiquity: AD 150-750. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95803-4.

- Donahue, John R.; Harrington, Daniel J. (2005). The Gospel of Mark. Sacra Pagina. Vol. 2. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5965-6.

- Edwards, James R. (1989). "Markan Sandwiches the Significance of Interpolations in Markan Narratives". Novum Testamentum. 31 (3). Brill: 193–216. doi:10.1163/156853689x00207. ISSN 0048-1009. JSTOR 1560460.

- MacArthur, John (1987). Matthew 8-15 MacArthur New Testament Commentary. Chicago: Moody Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57567-678-4.

- Schaff, Philip; Wace, Henry, eds. (1890). A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Series 2. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Schiller, Gertrud (1971). Iconography of Christian Art. Vol. 1 : Christ's Incarnation. Childhood. Baptism. Temptation. Transfiguration. Works and Miracles. London: Lund Humphries. ISBN 9780853312703.

- Schiller, Gertrud (1972). Iconography of Christian Art. Vol. 2: The Passion of Christ. London: Lund Humphries. ISBN 9780821203651.

- Shepherd, Tom (1995). "The Narrative Function of Markan Intercalation". New Testament Studies. 41 (4). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 522–540. doi:10.1017/s0028688500021688. ISSN 0028-6885. S2CID 170266008.

- Souvay, Charles Léon (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Strong, James (1894). The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. New York: Hunt & Eaton.

- Wace, Henry (1911). Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature. London: J. Murray.

- Wilson, John Francis (2004). Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the Lost City of Pan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-440-5.