Connecticut Colony

Colony of Connecticut | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1636–1776 | |||||||

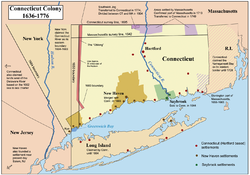

A map of the Connecticut, New Haven, and Saybrook colonies. | |||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||

| Capital | Before 1701: Hartford, 1701-1776: Joint Capitals: Hartford (May Legislative session) and New Haven (October Legislative session) | ||||||

| Common languages | English | ||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||

| Legislature | Fundamental Orders of Connecticut | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 1636 | ||||||

| 1776 | |||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||

| |||||||

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in British America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritan noblemen. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English gained control of the colony permanently by the late 1630s. The colony was later the scene of a bloody war between the English and Indians, known as the Pequot War. It played a significant role in the establishment of self-government in the New World with its legendary refusal to surrender local authority to the Dominion of New England, an event known as the Charter Oak incident.

Two other English colonies in the present-day state of Connecticut were merged into the Colony of Connecticut: Saybrook Colony in 1644 and New Haven Colony in 1662.

History

By 1630, the English, the Dutch's main rival in North America, had established several settlements on the eastern coast of New England, including Plymouth Colony in 1620, New Hampshire Colony in 1623, and Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. King James I of England granted the Earl of Warwick, president of the Council for New England, the right to settle the area west of Narragansett Bay to the Pacific Ocean. In 1631, the Earl of Warwick conveyed the grant to 15[citation needed] Puritan lords in England as a potential refuge in North America. The patentees included William Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele, as well as Lord Brooke, and Colonel George Fenwick. In 1635, the patentees commissioned John Winthrop, Jr., son of the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, as "Governor of River Colony".

Winthrop arrived in Boston in October 1635 and learned that the Dutch were planning to occupy the mouth of the Connecticut River at a place called Pasbeshauke, meaning "place at the mouth of the river" in the Algonquian language. To counter the Dutch, Winthrop sent a small bark (canoe) to the mouth of the Connecticut with 20 carpenters and other workmen under the leadership of Lieutenant Edward Gibbons and Sergeant Simon Willard. The expedition landed near the mouth of the river, on the west bank in present-day Old Saybrook, on November 24, 1635 and located the Dutch coat of arms nailed on a tree. They tore down the coat of arms and replaced it with a shield painted with a grinning face. They established a battery of cannon and built a small fort. When the Dutch ship returned several days later, they sighted the cannon and the English ships and withdrew. Winthrop renamed the point "Point Sayebrooke" in honor of Fiennes (Viscount Saye) and Lord Brooke.

English settlers from other New England colonies moved into the Connecticut Valley in the 1630s. In 1633, William Holmes led a group of settlers from Plymouth Colony to the Connecticut Valley, where they established Windsor, a few miles north of the Dutch trading post. In 1634, John Oldham and a handful of Massachusetts families built temporary houses in the area of Wethersfield, a few miles south of the Dutch outpost. In the next two years, thirty families from Watertown, Massachusetts joined Oldham's followers at Wethersfield. The English population of the area exploded in 1636 when clergyman Thomas Hooker led 100 settlers, including Richard Risley, with 130 head of cattle in a trek from Newtown (now Cambridge) in the Massachusetts Bay Colony to the banks of the Connecticut River, where they established Hartford directly across the Park River from the old Dutch fort. In 1637, the three Connecticut River towns—Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield—set up a collective government in order to fight the Pequot War. These settlers sought to establish a new ecclesiastical society subject to their own rules and regulations. According to historian Henry S. Cohn:[1] "They resented the power of the Magistrates who were not elected by the people. But they also wanted to expand their land holdings..."

In the Summer of 1638, the towns drew up their Fundamental Orders, setting out the principles, powers, and structure of the government. These were adopted by the Connecticut council on January 14, 1639 and transcribed into the official record by Thomas Welles. Connecticut received a royal charter in 1662 and became an official crown colony.

The New Haven Colony was a separate entity; it was merged into Connecticut under the 1662 charter. (The citizens of New Haven may have first recognized Connecticut authority on January 5, 1665.[citation needed]) The New Haven Colony combined with Connecticut largely due to pressure from England, as New Haven had harbored three of the judges who had condemned King Charles I to death in 1649. When the charter was later on to be confiscated a citizen hid it in an Oak tree's trunk.

The New Haven Colony in 1641 in an agreement with the Lenape tribe was to claim that it owned all the land east and west of the Delaware River. The Colony was to set up the first settlement of any kind in modern Philadelphia. Residents of New Sweden and New Amsterdam who lived in the area burned the community and it was disavowed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. While New Haven was to retreat from the venture, the Lenape agreement was to form the basis of a Connecticut sea to sea claim of owning all the land east and west of the Delaware from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Leaders

Thomas Hooker, a prominent Puritan minister, and Governor John Haynes of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who led 100 people to present day Hartford in 1636, are often considered the founders of the Connecticut colony. The sermon Hooker delivered to his congregation on the principles of government on May 31, 1638 influenced those who would write the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut later that year. The Fundamental Orders may have been drafted by Roger Ludlow of Windsor, the only trained lawyer living in Connecticut in the 1630s, and were transcribed into the official record by the secretary, Thomas Welles.

The Rev. John Davenport and merchant Theophilus Eaton are considered the founders of the New Haven Colony, which would be absorbed into Connecticut Colony in the 1660s.

In the colony's early years, the governor could not serve consecutive terms. Thus, for twenty years, the governorship often rotated between John Haynes and Edward Hopkins, both of whom were from Hartford. George Wyllys, Thomas Welles, and John Webster, also Hartford men, sat in the governor's chair for brief periods in the 1640s and 1650s.

John Winthrop, Jr. of New London, the son of the founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, played an important role in consolidating separate settlements on the Connecticut River into a single colony; and he served as Governor of Connecticut from 1659 to 1675. Winthrop was also instrumental in obtaining the colony's 1662 charter, which incorporated New Haven into Connecticut. His son, Fitz-John Winthrop, would also govern the colony for ten years, starting in 1698.

Roger Ludlow was an Oxford-educated lawyer and former Deputy Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who petitioned the General Court for rights to settle the area. Ludlow led the March Commission in settling disputes over land rights. He is credited as drafting the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1650) in collaboration with Hooker, Winthrop, and others. Ludlow was the first Deputy Governor of Connecticut.

William Leete of Guilford served as governor of New Haven Colony before that colony's merger into Connecticut, and as governor of Connecticut following John Winthrop, Jr's death in 1675. He is the only man to serve as governor of both New Haven and Connecticut.

Robert Treat of Milford served as governor of the colony both prior to and after its inclusion in Sir Edmund Andros's Dominion of New England. His father, Richard Treat, was one of the original patentees of the colony.

The colony enjoyed a string of strong governors in the 18th century, many being re-elected yearly until they died. Upon the death of Fitz-John Winthrop, Gurdon Saltonstall, Winthrop's minister in New London, was elected governor. Saltonstall was the only minister to serve as governor of Connecticut, and he belies the common misconception that Puritan clergy could not hold political office. Upon Saltonstall's death, Deputy Governor Joseph Talcott of Hartford became governor. Deputy Governor Jonathan Law of Milford succeeded to the position of governor upon Talcott's death. When Jonathan Law died, Deputy Governor Roger Wolcott of Windsor became governor. Wolcott, the father of Declaration of Independence signer Oliver Wolcott, was voted out of office in 1754 for his role in the Spanish Ship Case. Wolcott's successor, Thomas Fitch of Norwalk, guided the colony through the Seven Years' War, but was, himself, voted out of office in 1766 for not being strong enough in his repudiation of the Stamp Act. William Pitkin of Hartford (now East Hartford), the man who defeated Fitch, was a leader in the Sons of Liberty and also the cousin of former governor Roger Wolcott. Pitkin died in office in 1769, and was replaced by Deputy Governor Jonathan Trumbull, a merchant from Lebanon. Trumbull, also a supporter of the Sons of Liberty, continued to be elected governor throughout the Revolutionary War and retired as governor in 1784, the year after the signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which granted the United States its independence from Great Britain.

Role of religion

Like Massachusetts Bay Colony, Connecticut was founded by Puritans who made the Congregational Church the established church in the colony. Tax revenues supported the local ministers, and colonists who failed to attend Sunday services were subject to fines. Until 1708, the Congregational Church was the only legal religion in Connecticut. That year, however, the colony recognized "sober dissent", and excused certain dissenters, notably Anglicans and Baptists, from paying taxes to support the state church, provided, of course, that they contributed to their own lawful dissenting church. Also in 1708, the colony adopted the Saybrook Platform, which took church sovereignty away from the local congregations and placed it in the hands of a colony-wide consociation controlled by ministers.

In 1701, the General Assembly authorized the formation of the Collegiate School, with the mission of training new Congregational ministers in the colony. After locating in Killingworth, Saybrook, and Wethersfield, the school found a permanent home in New Haven in 1716. In 1718, following a substantial gift from Elihu Yale, a wealthy English businessman who had been born in Boston, the institution's name was changed to Yale College. In the early 1720s, religious controversy gripped Yale, as the school's rector, Rev. Timothy Cutler, along with one of the tutors and two neighboring ministers were accused of converting to Anglicanism. Determined to enforce orthodoxy at the institution, in 1722 the school's trustees dismissed Rev. Cutler and the offending tutor, and adopted a resolution requiring that, in the future, all rectors and tutors must declare their assent to the Saybrook Platform.

The Great Awakening sent shock waves through the colony in the middle of the eighteenth century, ripping the Congregational Church apart. Those who embraced the Awakening were known as New Lights, while those opposed to it became known as Old Lights. Unhappy with the often unemotional services of their regular ministers, New Lights in many towns petitioned to form separate religious societies or churches. Often Old Lights would oppose these attempts, arguing that the New Lights were neither sober (because of the emotional nature of their services) nor dissenting (because they continued to be Congregationalists). In 1741, Old Lights who tried to suppress the Awakening succeeded in convincing the General Assembly to pass an Itineracy Law, which prohibited traveling ministers from preaching in a Connecticut town without an invitation from the town's minister. Many historians believe that this law was the spark that led to the creation of issue politics in the colony.

During the American Revolution many of the colony's Anglicans, most of whom were concentrated in Fairfield County, remained Loyalists. One Anglican, Moses Dunbar of Bristol, was convicted of treason and hanged for being a Loyalist.

Congregationalism remained the established church in Connecticut throughout the Revolutionary Period, although, with time, more denominations were exempted as "sober dissenting" churches. With the adoption of Connecticut's 1818 state constitution, the Congregational Church was disestablished.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

See also

Notes

- ^ Cohn, Henry S., Connecticut Colonial History 1636-1776, Connecticut State Library