Cliff House, San Francisco

| Cliff House | |

|---|---|

Cliff House from Ocean Beach, 2010 | |

| |

| Restaurant information | |

| Established | 1863 |

| Street address | 1090 Point Lobos Ave |

| City | San Francisco |

| State | California |

| Postal/ZIP Code | 94121 |

| Coordinates | 37°46′42″N 122°30′50″W / 37.778394°N 122.513935°W |

| Website | Official website |

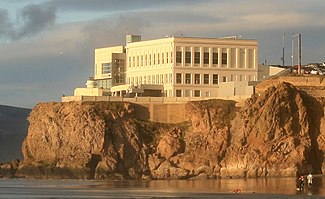

The Cliff House is a neo-classical style building perched on the headland above the cliffs just north of Ocean Beach, in the Outer Richmond neighborhood of San Francisco, California. The building overlooks the site of the Sutro Baths ruins, Seal Rocks, and is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, operated by the National Park Service (NPS). The Cliff House is owned by the NPS; the building's terrace hosts a room-sized camera obscura.

For most of the Cliff House's history, since 1863, the building's main draw has been restaurants and bars where patrons could enjoy the Pacific Ocean views. Since 1977, these restaurants and bars have been run by a private operator under contract with the National Park Service. In December 2020, the 47-year operator of these amenities announced that it was closing, and it criticized the NPS for not having signed a new long-term lease with any operator since its own prior 20-year lease had expired in June 2018.[1][2][3]

Dozens of ships have run aground on the southern shore of the Golden Gate below the Cliff House.[4]

First Cliff House (1863–1894)

[edit]

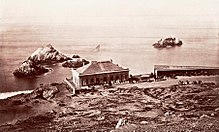

Anecdotal stories claim that in 1858 Samuel Brannan paid $1,500 for lumber salvaged from a ship that foundered on the rocky shore's basalt cliffs near Seal Rocks[5] and built the first Cliff House. While Brannan may have constructed a building there, no historical evidence of this building exists and its role in the origin of the Cliff House remains apocryphal.[6] The Cliff House was built by Senator John Buckley and C. C. Butler, opened in 1863 and leased to Captain Junius G. Foster.[7][8][9] It was a long trek on foot from the city and the restaurant hosted mostly horseback riders, small-game hunters or picnickers on day outings. With the opening of the privately built Point Lobos toll road a year later, the Cliff House became a Sunday destination among the carriage trade. Later the builders of the toll road constructed a two-mile speedway adjacent to it where well-to-do San Franciscans raced their horses along the way. On weekends, there was little room at the Cliff House hitching racks for tethering the horses for the thousands of rigs. Soon, omnibus, railways and streetcar lines made it to near Lone Mountain where passengers transferred to stagecoach lines to the beach. The growth of Golden Gate Park attracted beach travelers, in search of meals and a look at the sea lions sunning themselves on Seal Rocks just off the cliffs, to visit the area. In 1877, the toll road, now Geary Street, was purchased by the city for approximately $25,000.

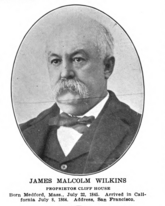

In 1883, after a few years of downturn, the Cliff House was bought by Adolph Sutro, who had made a fortune in silver by solving the problems of ventilating and draining the mines of Nevada's Comstock Lode. After a few years of quiet management by James M. Wilkins, the Cliff House was severely damaged when the schooner Parallel, abandoned with burning oil lamps and a cargo including dynamite powder, exploded while aground at Lands End early in the morning of January 16, 1887. The blast was heard a hundred miles away[10] and demolished the entire north wing of the tavern. The building was repaired, but was later completely destroyed by fire on Christmas night 1894 due to a defective flue.[9][11] Wilkins was unable to save the guest register, which included the signatures of three U.S. Presidents and dozens of world-famous visitors. This incarnation of the Cliff House, with its various extensions, had lasted for 31 years.

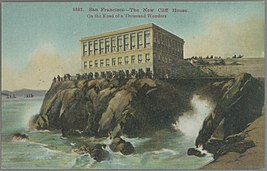

Second Cliff House (1896–1907)

[edit]

In 1896, Adolph Sutro rebuilt the Cliff House from the ground up as a seven-story Victorian chateau, called by some "the Gingerbread Palace", below his estate on the bluffs of Sutro Heights. This was the same year work began on the Sutro Baths in a small cove immediately north of the restaurant. The baths included six of the large indoor swimming pools, a museum, a skating rink and other pleasure grounds. Great throngs of San Franciscans arrived on steam trains, bicycles, carts and horse wagons on Sunday excursions. Sutro purchased some of the collection of stuffed animals, artwork, and historic items from Woodward's Gardens to display at both the Cliff House and Sutro Baths.[12]

The 1896 Cliff House survived the 1906 earthquake with little damage, but burned to the ground on the evening of September 7, 1907.[10]

Third Cliff House (1909–present)

[edit]1909–1937

[edit]

After the fire, Dr. Emma Merritt, Sutro's daughter, commissioned Reid & Reid to rebuild the restaurant in a neo-classical style. It was completed within two years and is the basis of the structure seen today. In 1914, the guidebook Bohemian San Francisco described it as "one of the great Bohemian restaurants of San Francisco. ... while you have thought you had good breakfasts before this, you know that now you are having the best of them all."[13]

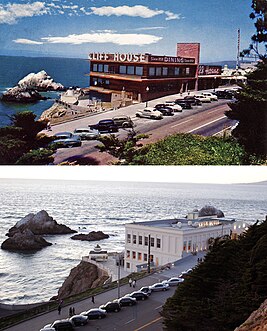

Bottom: Third Cliff House, 2009, following 2004 renovation to original 1909 aesthetic

1937–2003

[edit]In 1937, George and Leo Whitney purchased the Cliff House, to complement their Playland-at-the-Beach attraction nearby, and extensively remodelled it into an American roadhouse. From 1955 to 1966, a "Sky Tram" operated across the Sutro Baths basin, taking up to 25 visitors at a time from Point Lobos, enhanced by an artificial waterfall, to the outer balcony of the Cliff House.[14]

In 1972, upon the closing of Playland, the Musée Mécanique, a museum of 20th-century penny arcade games, was moved into the basement of the Cliff House.[15] In the early 1970s the land-side exterior of the building was decorated with an expansive mural painting depicting crashing waves, painted by artist-musicians (and future members of San Francisco rock band The Tubes) Michael Cotten and Prairie Prince.

The building was acquired by the National Park Service (NPS) in 1977 and became part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. In connection with this acquisition, the NPS contracted with Dan and Mary Hountalas as official concessionaires of the property. The NPS renewed its contract with the Hountalas family in 1998, through the family's company, Peanut Wagon, Inc.[16]

2003–2020

[edit]In 2003, as part of an extensive renovation, many of Whitney's additions were removed and the building was restored to its 1909 appearance. A new two-story wing was constructed overlooking what were by then the ruins of the Sutro Baths. (The Baths burned to the ground on June 26, 1966.[10]) During the site restoration, the Musée Mécanique was moved to Fisherman's Wharf.[15]

The Cliff House had two restaurants, the casual dining Bistro Restaurant and the more formal Sutro's. Additionally, the Terrace Room served a Sunday brunch buffet. There was a gift shop in the building, and the historic camera obscura is on a deck overlooking the ocean. Peanut Wagon continued to manage Cliff House operations and worked with the Park Service during the extensive site restoration that was completed in 2004.

During the 2013 government shutdown, October 1–17, the US Park Service ordered the restaurant closed. The owners defied the order, but were forced to close. They reopened with permission on October 12, 2013.[17]

2021 closure and future prospects

[edit]The concessionaires of the Cliff House reported on December 13, 2020, that they would be closing their doors on December 31, 2020. They blamed losses from the closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and their landlord, the National Park Service (NPS), for delaying a long term-lease; the restaurant had been operating under a series of short-term leases since June 2018.[1][2][3] According to the National Park Service's website, a 3.5-year lease had been offered to the vendor (the Hountalas family doing business as Peanut Wagon Inc.) on December 30, which was turned down. On December 31, 2020, the Cliff House's sign was removed.[18]

The NPS says that it "is committed to maintaining this iconic building", but that the "solicitation process [for a new vendor] for this operation is currently paused as a result of the pandemic."[19] On February 2, 2021, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a resolution urging the NPS to find an immediate vendor for the restaurant while it searched for a long-term tenant. The Park Service confirmed that they planned to do so.[20]

Trademark issues

[edit]In the wake of the departure of the Hountalas family and its company as the private concessionaire for the Cliff House, it emerged that the company had secured certain "Cliff House"-related trademarks. This led news organizations to speculate as to whether a future concessionaire would be able to use the "Cliff House" name to protect and promote the identity of the institution.[21][22]

In popular culture

[edit]

- The area immediately around the Cliff House is part of the setting of Jack London's novel The Scarlet Plague (1912).[23]

- Jack London also sets the meeting of Maud Sangster and Pat Glendon Jr. here in The Abysmal Brute (1913).

- Wallace Stegner refers to the Cliff House in his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose in a letter from Susan Ward to her friend Augusta, in which she describes a visit to San Francisco in 1867 (1971).[24]

- An image of the second Cliff House was used on the cover of the album Imaginos by Blue Öyster Cult.

- The Cliff House appears in a scene in the 1948 film Race Street, starring George Raft.

- The Cliff House is featured in the Ubisoft video game Watch Dogs 2.

- The Cliff House appears briefly in the climax of the 1958 film The Lineup, at Sutro Baths, starring Eli Wallach and directed by Don Siegel.

- Robert Frost references the Cliff House in his poem "A Record Stride" (A Further Range, 1936).

- Scenes were shot at the third Cliff house for the 1924 film Greed

Further reading

[edit]- O'Brien, Robert (1948). This is San Francisco. New York: Whittlesey House. OCLC 1488183.

- Cliff House - Historic Structure Report at National Park Service

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b Gafni, Matthias (December 14, 2020). "S.F.'s iconic Cliff House restaurant to shut down". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (December 13, 2020). "Historic Cliff House in San Francisco to Close Permanently". KPIX 5 CBS San Francisco. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Closure of iconic Cliff House ends a remarkable era of San Francisco's history". The Guardian. December 20, 2020.

- ^ Delgado, James (1 July 2009). Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks. Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Limited. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-926685-60-1.

- ^ Chamings, Andrew (December 15, 2020). "Here's the fiery, doomed history of San Francisco's Cliff House". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "First Cliff House". Cliff House Project. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Wrench, Kirk. "Cliff House". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ 1863 at Cliff House Project

- ^ a b "Ashen Heaps", The Morning Call, December 26, 1894, p. 1 Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine (bottom of column 6: "The house was opened in October, 1863...").

- ^ a b c Christine Miller, "Cliff House Disasters", GGNRA ParkNews, Fall 2002, via Outside Lands, October 4, 2002.

- ^ "Cliff House Gone". The San Francisco Chronicle. 26 December 1894.

- ^ Peter Hartlaub, "Woodward's Gardens Comes to Life in New Book", San Francisco Chronicle (October 30, 2012).

- ^ Bohemian San Francisco -- Its Restaurants and Their Most Famous Recipes—The Elegant Art of Dining, 1914, by Clarence E. Edwords

- ^ Van Niekerken, Bill (October 17, 2016). "San Francisco's Sky Tram, a tourist oddity lost to history". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b "Defending a Museum". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "National Park Service Issues New Contract to Long-Time Cliff House Concessioner". Business Wire. October 5, 1998. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Cliff House reopens despite government shutdown (again), with federal permission, Inside Scoop SF, October 12, 2013

- ^ "Hundreds gather as Cliff House's sign comes down, marking the official closure of iconic S.F. restaurant". San Francisco Chronicle. December 31, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Status of the Cliff House and Lookout Cafe (Lands End Restaurant Properties)" Golden Gate National Recreation Area, National Park Service

- ^ Bitker, Janells (February 4, 2021) "San Francisco's Cliff House likely returning as a restaurant after all, landlords say" San Francisco Chronicle

- ^ John Lumea, "The 5 Hountalas Trademarks for The Cliff House, San Francisco," Medium, February 8, 2021.

- ^ John Lumea, "Does the Bank Still Have a Claim on the Hountalas Trademarks for The Cliff House, San Francisco?" Medium, February 19, 2021.

- ^ London, Jack (June 1912). "The Scarlet Plague". London Magazine. 28: 513–540. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Stegner, Wallace (November 2014). Angle of Repose. Vintage Books. p. 120.

External links

[edit]- Official National Park Service page

- Cliff House Project

- CliffHouse.com (website of Peanut Wagon, Inc., concessionaire 1973–2020)

- Radio episode of "Fog", California Legacy Project — from Mark Twain's "Early Rising as Regards Excursions to the Cliff House," published in The Golden Era magazine, 1864.

- Cliff House renovation, 1998-2006. Collection guide, California State Library, California History Room.

- c.1902 photograph of the Cliff House by Robert Augustus Henry L'Estrange (1858-04-08 Rathmines, Dublin, Ireland...1941-20-03 Brisbane, Australia)

- National Park Service areas in California

- Golden Gate National Recreation Area

- Landmarks in San Francisco

- Restaurants in San Francisco

- Richmond District, San Francisco

- 1863 establishments in California

- Restaurants established in the 19th century

- Buildings and structures completed in 1863

- Buildings and structures completed in 1896

- Buildings and structures completed in 1909

- Reid & Reid buildings

- Neoclassical architecture in California

- Gilded Age mansions