Clarín (Argentine newspaper)

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (August 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

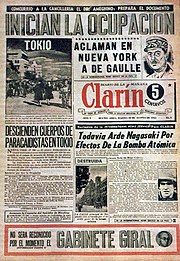

Front page of Clarín from 13 December 2015 | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid |

| Owner(s) | Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino S.A. (Clarín Group) |

| Publisher | Héctor Magnetto |

| Editor-in-chief | Ricardo Kirschbaum |

| Managing editor | Ricardo Roa |

| Founded | 28 August 1945 |

| Political alignment | Social liberalism[1][2][3][4][5] Formerly: Developmentalism[6] |

| Headquarters | Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Circulation | 270,444 (Print, 2012) 100,000 (Digital, 2018)[7] |

| Website | www |

Clarín (Spanish pronunciation: [klaˈɾin], lit. 'Bugle') is the largest newspaper in Argentina and the second most circulated in the Spanish-speaking world. It was founded by Roberto Noble in 1945, published by the Clarín Group.[8][9]

For many years, its director was Ernestina Herrera de Noble, the founder's wife.[10]

Clarín is part of Periódicos Asociados Latinoamericanos (Latin American Newspaper Association), an organization of fourteen leading newspapers in South America.

History

[edit]

Clarín was created by Roberto Noble, former minister of the Buenos Aires Province, on 28 August 1945. It was one of the first Argentine newspapers published in tabloid format. It became the highest sold Argentine newspaper in 1965, and the highest sold Spanish-speaking newspaper in 1985. It was also the first Argentine newspaper to sell a magazine with the Sunday edition, since 1967. In 1969, the news were split into several supplements by topic. In 1976, high color printing was benefited by the creation of Artes Gráficas Rioplatense (AGR).

For many years the Argentine author Horacio Estol was the New York correspondent of Clarín, writing about aspects of US life of interest to Argentines.[11]

Roberto Noble died in 1969, and his widow Ernestina Herrera de Noble succeeded him as director. The newspaper bought Papel Prensa in 1977, together with La Nación and La Razón. In 1982, it joined a group of 20 other newspapers to create the "Diarios y Noticias" informative agency. The Sunday magazine was renamed in 1994 to "Viva", a name that would last up to the modern day. The newspaper started a media conglomerate in 1999 after a law reformation which allows it to collect many media supports, that would be named after the newspaper, Grupo Clarín. This conglomerate would operate in radio, television, Internet, other newspapers and other areas beyond Clarín itself.

On 27 December 1999, The Clarín Group and Goldman Sachs, an American investment firm, subscribed an investment agreement where the consortium, managed by Goldman Sachs, made a direct investment in Clarín Group. The operation implied an increase of capital to the Clarín Group and the incorporation of Goldman Sachs as minority partner, with a participation of 18% of the stocks.[citation needed]

Clarín launched clarin.com, the website for the newspaper, in March 1996. The site served nearly 6 million unique visitors daily in Argentina in April 2011, making it the fifth most visited website in the country that month and the most widely visited of any website based in Argentina itself.[12]

Editorial stance

[edit]This newspaper is defined as an independent newspaper. This publication has always been identified by a centre-right editorial line and defends the developmentalist ideology.[13]

On 1946 general election Clarín supported José Tamborini, the candidate of the Radical Civic Union, against the populist Juan Perón. The newspaper declared that "the Argentine people are aware that they vote for the maintenance of the Constitution of Argentina and the basic laws of the republic, for the institutional order, for the regime of freedom and for the honorable Argentine tradition."[14]

Clarín was in favor of Revolución Libertadora, which overthrew Juan Domingo Perón in 1955.[15] On September 22, it published the biography of Eduardo Lonardi.[16] The next day it wrote: "An appointment of honor with freedom. For the Republic, too, the night is behind us. Enthusiastic and standard bearer of Buenos Aires incident to Lonardi."[16]

The most distinctive feature of this newspaper was its adherence to developmentalism, a ideology it maintained until the 1980s. It has been identified with the industry and is considered an 'industrialist' newspaper.[17]

Hector Magnetto, now publisher of the newspaper, was hired as an advisor to Ernestina Herrera de Noble on March 2, 1972, and was affiliated with the pro-industry political party, the Integration and Development Movement (MID).

Despite its large circulation, Clarín suffered financial difficulties when Mrs. Noble inherited the director's post from its founder, Roberto Noble, as his widow. She turned to one of the latter's most prominent allies, economist and wholesaler Rogelio Julio Frigerio, who lent Clarín US$10 million in 1971. The paper continued to endorse Frigerio's centrist MID platform, which centered on government support for infrastructure investment and import substitution industrialization. On Frigerio's advice, Mrs. Noble brought in Magnetto, who took later charge of the newspaper's finances.[citation needed]

Néstor Kirchner, close to Magnetto, renewed the group's transmission licenses for 10 years in 2005 and later approved the acquisition of cable company Cablevisión. But relations collapsed in 2008 when Clarín backed farmers through export taxes.[18]

The magazine "Noticias", from the newspaper Perfil, accused Clarín of having signed a "pact" with Néstor Kirchner. He denounced the former president used the newspaper as his own news agency. According to Darío Gallo, one of the Perfil Editors, the investigation points to "Grupo Clarin's new businesses in the telecommunications market that need government support."[19]

President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's battle with the press intensified when she implemented a controversial media law that, according to her administration, encourages plurality of voices and that opponents call an attack on freedom of expression and democracy.[18]

Clarín, once an ally of Cristina Kirchner and her late husband and predecessor, was now openly opposed to the government. The group owns Argentina's best-selling newspaper and controls 59 and 42 percent of the cable TV and radio markets, respectively, according to AFSCA, the law enforcement agency.[18]

Some feared that the media law could lead to a deficit of independent reporting: Clarín is one of the few news organizations that does not depend on the government through advertising subsidies. "There is no freedom of expression without an independent press", said Héctor Magnetto, general director of Clarín. "If one weakens, both could be at risk."[18]

Circulation

[edit]Clarín prints and distributes around 330,000 copies throughout the country, but by 2012, circulation had declined to 270,444 copies and Clarín accounted for nearly 21 percent of Argentine newspaper market, compared to 35 percent in 1983.[7] Clarín has a 44 percent market share in Buenos Aires.

According to third-party web analytics providers Alexa and SimilarWeb, Clarín's website is the 10th and 14th most visited in Argentina respectively, as of August 2015.[20][21] SimilarWeb rates the site as the 3rd most visited news website in Argentina, attracting almost 32 million visitors per month.[21][22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Montero, Julio (4 March 2019). "El verdadero progresismo es liberal". www.clarin.com.

- ^ Santibañes, Francisco de (12 September 2019). "Un mundo menos liberal y más conservador". clarin.com.

- ^ Lasalle, José María (24 February 2020). "Liberalismo vs. populismo". clarin.com.

- ^ "Al liberalismo no le preocupa la desigualdad". clarin.com. 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Liberalismo no se reduce a libre mercado". clarin.com. 7 April 2017.

- ^ https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7442024.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b "Clarín vende un 32% menos que en 2003 y reduce su presencia en el mercado de diarios (Clarin sells 32% less than in 2003 and reduced its presence in the market daily)". Telam. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Pressed". The Economist. 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Nuestros Valores".

- ^ "Origin and Evolution". grupoclarin.com. Grupo Clarín. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "After Half a Century and 200 Issues ..." Automóvil Club Argentino. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Facebook Users in Argentina Spend 9 Hours a Month on Site, Second Only to Israel in User Engagement". comScore. 9 June 2011.

- ^ "Los 24 Periódicos de Izquierda y Derecha Más Importantes". Lifeder. 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Clarín: 75 años de antiperonismo". infocielo.com (in Spanish). 22 December 2023.

- ^ De la mano de un político conservador, hace 75 años nacía Clarín by Claudia Ferri, La Izquierda Diario, 27 Aug 2020

- ^ a b "Mirá esta nota para entender porque Clarín no llama Golpe al Golpe". www.enorsai.com.ar.

- ^ "Símbolo de 'La Nación'". Perfil. 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Jonathan (5 December 2012). "Showdown looms between Argentina's Kirchner and her biggest media critic". CS Monitor.

- ^ "Señales: El pacto Kirchner-Clarín, es por Telecom". 1 March 2008.

- ^ "clarin.com Site Overview". Alexa. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Clarin.com Analytics". SimilarWeb. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "Top 50 sites in Argentina for News And Media". SimilarWeb. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to Clarín at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Clarín at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- The Holding (in Spanish)

- Clarín's Profile on InfoAmerica