Christian art: Difference between revisions

Calabe1992 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by Carlos a cazares (talk) identified as unconstructive (HG) |

Carlos Cazares quotation marks, to add my bio in the future |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

===The re-birth of Christian fine art=== |

===The re-birth of Christian fine art=== |

||

The last part of the 20th and the first part of the 21st century have seen a focused effort by artists who claim faith in Christ to re-establish art with themes that revolve around faith, Christ, God, the Church, the Bible and other classic Christian themes as worthy of respect by the secular art world. Some writers, such as Gregory Wolfe, view this resurgence as part of a larger rebirth of Christian humanism<ref>{{cite book|last=Wolfe|first=Gregory|title=Beauty Will Save the World: Recovering the Human in an Ideological Age|year=2011|publisher=Intercollegiate Studies Institute|isbn=978-1933859880|pages=278|url=http://www.amazon.com/Beauty-Will-Save-World-Ideological/dp/1933859881}}</ref>. Artists such as [[Makoto Fujimura]] have had significant influence both in sacred and secular arts. Other notable artists include Gary P. Bergel, Carlos Cazares, Bruce Herman, Deborah Sokolove, and [[John August Swanson]]. |

The last part of the 20th and the first part of the 21st century have seen a focused effort by artists who claim faith in Christ to re-establish art with themes that revolve around faith, Christ, God, the Church, the Bible and other classic Christian themes as worthy of respect by the secular art world. Some writers, such as Gregory Wolfe, view this resurgence as part of a larger rebirth of Christian humanism<ref>{{cite book|last=Wolfe|first=Gregory|title=Beauty Will Save the World: Recovering the Human in an Ideological Age|year=2011|publisher=Intercollegiate Studies Institute|isbn=978-1933859880|pages=278|url=http://www.amazon.com/Beauty-Will-Save-World-Ideological/dp/1933859881}}</ref>. Artists such as [[Makoto Fujimura]] have had significant influence both in sacred and secular arts. Other notable artists include Gary P. Bergel, [[Carlos Cazares]], Bruce Herman, Deborah Sokolove, and [[John August Swanson]]. |

||

==Themes== |

==Themes== |

||

Revision as of 04:43, 2 December 2011

Christian art is sacred art produced in an attempt to illustrate, supplement and portray in tangible form the principles of Christianity, though other definitions are possible. Most Christian groups use or have used art to some extent, although some have had strong objections to some forms of religious image, and there have been major periods of iconoclasm within Christianity. Images of Jesus and narrative scenes from the Life of Christ are the most common subjects, and scenes from the Old Testament play a part in the art of most denominations. Images of the Virgin Mary and saints are much rarer in Protestant art than that of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Of the three related religions Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, Christianity makes far wider use of images, which are forbidden or discouraged by Islam and Judaism. However there is also a considerable history of aniconism in Christianity from various periods.

History

Beginnings

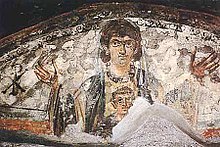

Early Christian art survives from dates near the origins of Christianity. The oldest surviving Christian paintings are from the site at Megiddo, dated to around the year 70, and the oldest Christian sculptures are from sarcophagi, dating to the beginning of the 2nd century. The largest groups of Early Christian paintings come from the tombs in the Catacombs of Rome, and show the evolution of the depiction of Jesus, a process not complete until the 6th century, since when the conventional appearance of Jesus in art has remained remarkably consistent. Until the adoption of Christianity by Constantine Christian art derived its style and much of its iconography from popular Roman art, but from this point grand Christian buildings built under imperial patronage brought a need for Christian versions of Roman elite and official art, of which mosaics in churches in Rome are the most prominent surviving examples. Christian art was caught up in, but did not originate, the shift in style away from the classical tradition inherited from Ancient Greek art to a less realist and otherworldly hieratic style, the start of medieval art.

Middle Ages

Much of the art surviving from Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire is Christian art, although this in large part because the continuity of church ownership has preserved church art better than secular works. While the Western Roman Empire's political structure essentially collapsed after the fall of Rome, its religious hierarchy, what is today the modern-day Roman Catholic Church funded and supported production of sacred art. The Orthodox Church of Constantinople, which enjoyed greater stability within the surviving Eastern Empire was key in funding arts there, and glorifying Christianity. As a stable Western European society emerged during the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church led the way in terms of art, using its resources to commission paintings and sculptures.

During the development of Christian art in the Byzantine empire (see Byzantine art), a more abstract aesthetic replaced the naturalism previously established in Hellenistic art. This new style was hieratic, meaning its primary purpose was to convey religious meaning rather than accurately render objects and people. Realistic perspective, proportions, light and color were ignored in favor of geometric simplification of forms, reverse perspective and standardized conventions to portray individuals and events. The controversy over the use of graven images, the interpretation of the Second Commandment, and the crisis of Byzantine Iconoclasm led to a standardization of religious imagery within the Eastern Orthodoxy.

Renaissance and Early Modern period

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought an end to the highest quality Byzantine art, produced in the Imperial workshops there. Orthodox art, known as icons regardless of the medium, has otherwise continued with relatively little change in subject and style up to the present day, with Russia gradually becoming the leading centre of production.

In the West, the Renaissance saw an increase in monumental secular works, but until the Protestant Reformation Christian art continued to be produced in great quantities, both for churches and clergy and for the laiety. The Reformation had a huge effect on Christian art, rapidly bringing the production of public Christian art to a virtual halt in Protestant countries, and causing the destruction of most of the art that already existed. Artists switched to secular genres like portraits, landscape paintings and, ironically, subjects from classical mythology, now more acceptable subjects than saints. In Catholic countries, production continued, and increased during the Counter-Reformation, but Catholic art was brought under much tighter control by the church hierarchy than had been the case before. From the 18th century the number of religious works produced by leading artists declined sharply, though important commissions were still placed, and some artists continued to produce large bodies of religious art on their own initiative.

Modern period

As a secular, non-sectarian, universal notion of art arose in 19th century Western Europe, ancient and Medieval Christian art began to be collected for art appreciation rather than worship, while contemporary Christian art was considered marginal. Occasionally, secular artists treated Christian themes (Bouguereau , Manet) — but only rarely was a Christian artist included in the historical canon (such as Rouault or Stanley Spencer). However many modern artists such as Eric Gill, Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Jacob Epstein, Elizabeth Frink and Graham Sutherland have produced well-known works of art for churches.[1]

Popular devotional art

Since the advent of printing, the sale of reproductions of pious works has been a major element of popular Christian culture. In the nineteenth century, this included genre painters such as Mihály Munkácsy. The invention of color lithography led to broad circulation of holy cards. In the modern era, companies specializing in modern commercial Christian artists such as Thomas Blackshear and Thomas Kinkade, although widely regarded in the fine art world as kitsch,[2] have been very successful.

The re-birth of Christian fine art

The last part of the 20th and the first part of the 21st century have seen a focused effort by artists who claim faith in Christ to re-establish art with themes that revolve around faith, Christ, God, the Church, the Bible and other classic Christian themes as worthy of respect by the secular art world. Some writers, such as Gregory Wolfe, view this resurgence as part of a larger rebirth of Christian humanism[3]. Artists such as Makoto Fujimura have had significant influence both in sacred and secular arts. Other notable artists include Gary P. Bergel, Carlos Cazares, Bruce Herman, Deborah Sokolove, and John August Swanson.

Themes

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Themes often seen in Christian art are:

See also

- Andachtsbilder

- Art in Roman Catholicism

- Buddhist art

- Christian icons

- Christian music

- Christian poetry

- Christian symbolism

- Crucifixion in the arts

- God the Father in Western art

- Holy Spirit in Christian art

- Iconography

- Illuminated manuscript

- Islamic art

- Islamic influences on Christian art

- Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art

- Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy

- Theological aesthetics

Notes

- ^ Beth Williamson, Christian Art: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (2004), page 110.

- ^ Cynthia A. Freeland, But Is It Art?: An Introduction to Art Theory, Oxford University Press (2001), page 95

- ^ Wolfe, Gregory (2011). Beauty Will Save the World: Recovering the Human in an Ideological Age. Intercollegiate Studies Institute. p. 278. ISBN 978-1933859880.

References

- Grabar, André (1968). Christian iconography, a study of its origins. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691018308.