Chinese unification

| Chinese unification | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Territory controlled by the People's Republic of China (purple) and the Republic of China (orange). The size of minor islands has been exaggerated in this map for ease of visibility. | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國統一 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国统一 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | China unification | ||||||

| |||||||

| Cross-Strait unification | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 海峽兩岸統一 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 海峡两岸统一 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Two shores of strait unification | ||||||

| |||||||

|

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

Chinese unification, also known as Cross-Strait unification or Chinese reunification, is the potential unification of territories currently controlled, or claimed, by the People's Republic of China ("China" or "Mainland China") and the Republic of China ("Taiwan") under one political entity, possibly the formation of a political union between the two republics. Together with full Taiwan independence, unification is one of the main proposals to address questions on the political status of Taiwan, which is a central focus of Cross-Strait relations.

Background

[edit]In 1895, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China lost the First Sino-Japanese War and was forced to cede Taiwan and Penghu to the Empire of Japan after signing the Treaty of Shimonoseki. In 1912, the Qing dynasty was overthrown and was succeeded by the Republic of China (ROC). Based on the theory of the succession of states, the ROC originally lay claim to the entire territory which belonged to the Qing dynasty during the time of its collapse, except for Taiwan, which the ROC recognized as belonging to the Empire of Japan at the time.[citation needed] The ROC managed to attain widespread recognition as the legitimate successor state to the Qing dynasty during the years following the fall of the Qing dynasty.[citation needed]

In the year 1945, the ROC won the Second Sino-Japanese War, which was intertwined with World War II, and took control of Taiwan on behalf of the Allied Powers, following the Japanese surrender. The ROC immediately asserted its claim to Taiwan as "Taiwan Province, Republic of China", basing its claim on the Potsdam Declaration and the Cairo Communique. Around this time, the ROC nullified the Treaty of Shimonoseki, declaring it to be one of the many "Unequal Treaties" imposed on China during the so-called "Century of Humiliation". At the time, the Kuomintang (KMT) was the ruling party of the ROC, and was widely recognized as its legitimate representative, especially due to the collaboration of its leader Chiang Kai-shek with the Allied Powers.[citation needed]

However, throughout much of the rule of the ROC, China had been internally divided during a period called the Warlord Era. According to the common narrative, the ROC was divided into many different ruling cliques and secessionist states, which were in a constant struggle following the power vacuum which was created after the overthrowing of the Qing Dynasty. During this period, two ruling cliques eventually came out on top; that of the KMT, backed by the United States, and that of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), backed by the Soviet Union. The power struggle between these two specific political parties has come to be known as the Chinese Civil War. The Chinese Civil War was fought sporadically throughout the ROC's history; it was interrupted by the Second Sino-Japanese War.[citation needed]

After the Second Sino-Japanese War concluded, the Chinese Civil War resumed, and the CCP quickly gained a huge advantage over the KMT (ruling the ROC). In 1949, the KMT evacuated its government, its military, and around 1.2–2 million loyal citizens to Taiwan, which had only been ruled by the KMT for around four years by this time. Back in mainland China, the CCP proclaimed the "People's Republic of China (PRC)", effectively creating a reality of Two Chinas. Following the creation of Two Chinas, the PRC began to fight a diplomatic war against the ROC on Taiwan over official recognition as the sole legitimate government of China. Eventually, the PRC (mostly) won this war, and ascended to the position of "China" in the United Nations in 1971, evicting the ROC from that position.[citation needed]

As a result, the ROC still governed Taiwan but was no longer recognized as a member state of the United Nations. In recent years, membership in the United Nations has become almost an essential qualifier of statehood. Most states with limited recognition are not at all recognized by most governments and intergovernmental organizations. However, the ROC is a unique case, given that it has still managed to attain a significant degree of unofficial international recognition, even though most countries do not officially recognize it as a sovereign state. This is mainly due to the fact that the ROC was previously recognized as the legitimate government of China, providing an extensive framework for unofficial diplomatic relations to be conducted between the ROC and other countries.[citation needed]

In the years following the ROC's retreat to Taiwan, Taiwan has gone through a series of significant social, political, economic, and cultural shifts, strengthening the divide between Taiwan and mainland China. This has been further exacerbated by Taiwan's history as a colony of the Japanese Empire, which led to the establishment of a unique Taiwanese identity and the desire for Taiwan independence. The Taiwan independence movement has grown considerably stronger in recent decades, and has especially become a viable force on the island ever since the ROC's transition to a multi-party system, during what has become known as the Democratization of Taiwan.[citation needed]

The PRC has never recognized the sovereignty of Taiwan. PRC asserts that the ROC ceased to exist in the year 1949 when the PRC was proclaimed. Officially, PRC refers to the territory controlled by Taiwan as Taiwan area, and to the government of Taiwan as the Taiwan authorities. PRC continues to claim Taiwan as its 23rd Province, and the Fujianese territories still under Taiwanese control as parts of Fujian Province. PRC has established the one China principle in order to clarify its intention. The CCP classifies Taiwan independence supporters as one of the Five Poisons.[1][2] In 2005, the 10th National People's Congress passed the Anti-Secession Law authorizing military force for unification.[3]

Most Taiwanese people oppose joining PRC for various reasons, including fears of the loss of Taiwan's democracy, human rights, and Taiwanese nationalism. Opponents either favor maintaining the status quo of the Republic of China administrating Taiwan or the pursuit of Taiwan independence.[4] The Constitution of the Republic of China states that its territory includes the mainland,[5] but the official policy of the Taiwanese government is dependent on which coalition is currently in power. The position of the Pan-Blue Coalition, which comprises the Kuomintang, the People First Party and the New Party is to eventually incorporate the mainland into the ROC, while the position of the Pan-Green Coalition, composed of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Taiwan Solidarity Union, is to pursue Taiwanese independence.[6]

In 2024, the Chinese government issued a directive to the courts stating that "diehard" independence supporters could be tried in absentia with capital punishment imposed.[7][8]

History

[edit]Mainland China

[edit]The concept of Chinese unification was developed in the 1970s as part of the CCP's strategy to address the "Taiwan issue" as China started to normalize foreign relations with a number of countries including the United States and Japan.[9][10]

According to the state-run China Internet Information Center, in 1979, the National People's Congress published the Message to Compatriots in Taiwan (告台湾同胞书) which included the term "Chinese reunification" as an ideal for Cross-Strait relations.[11][better source needed] In 1981, the Chairman of the People's Congress Standing Committee Ye Jianying announced the "Nine Policies" for China's stance on Cross-Strait relations, with "Chinese Peaceful Unification" (祖国和平统一) as the first policy.[12] According to Xinhua, since then, "one country, two systems" and "Chinese reunification" have been emphasized at every National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party as the principles to deal with Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. "One Country, Two Systems" is specifically about China's policy towards post-colonial Hong Kong and Macao, and "Chinese Unification" is specifically about Taiwan.[13] Taiwan has also been offered the resolution of "One Country, Two Systems”.[14][15]

Taiwan

[edit]Taiwan has a complicated history of being at least partially occupied and administered by larger powers including the Dutch East India Company, the Kingdom of Tungning (purporting to be a continuation of the Southern Ming), the Qing dynasty and the Empire of Japan. Taiwan first came under direct Chinese control when it was invaded by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in 1683.[16]

The island remained under Qing rule until 1895 when it was ceded to the Empire of Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Following the Axis powers' defeat in World War II in 1945, the Kuomintang-led Republic of China gained control of Taiwan.[16] Some Taiwanese resisted ROC rule in the years following World War II. The ROC violently suppressed this resistance which culminated in the February 28 Incident in 1947.[17] At the de facto end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950, KMT and CCP government faced each other across the Strait, with each aiming for a military takeover of the other.

From 1928 to 1942, the CCP maintained that Taiwan was a separate nation.[18] In a 1937 interview with Edgar Snow, Mao Zedong stated "we will extend them (the Koreans) our enthusiastic help in their struggle for independence. The same thing applies for Taiwan."[19]

The irredentist narrative emphasizing the importance of a unified Greater China area, which purportedly include Taiwan, arose in both the Kuomintang and the CCP in the years during and after the civil war. For the PRC, the claim of the Greater China area was part of a nationalist argument for territorial integrity. In the civil war years it set the communist movement apart from the ROC, which had lost Manchuria, the ancestral homeland of the Qing emperors, to Japan in 1932.[20]

Rise of Tangwai and Taiwanese nationalism

[edit]From the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950 until the mid-1970s the concept of unification was not the main subject of discourse between the governments of the PRC and the ROC. The Kuomintang believed that they would, probably with American help, one day retake mainland China, while Mao Zedong's communist regime would collapse in a popular uprising and the Kuomintang forces would be welcomed.[21]

By the 1970s, the Kuomintang's authoritarian military dictatorship in Taiwan, led by the Chiang family was becoming increasingly untenable due to the popularity of the Tangwai movement and Taiwanese nationalism. In 1970, then-Vice Premier, Chiang Ching-kuo survived an assassination attempt in New York City by Cheng Tzu-tsai and Peter Huang, both members of the World United Formosans for Independence. In 1976, Wang Sing-nan sent a mail bomb to then-Governor of Taiwan Province Hsieh Tung-min, who suffered serious injuries to both hands as a result.[22] The Kuomintang's heavy-handed oppression in the Kaohsiung Incident, alleged involvement in the Lin family massacre and the murders of Chen Wen-chen and Henry Liu, and the self-immolation of Cheng Nan-jung galvanized the Taiwanese community into political actions and eventually led to majority rule and democracy in Taiwan.

The concept of unification replaced the concept of liberation by the PRC in 1979 as it embarked, after Mao's death, on economic reforms and pursued a more pragmatic foreign policy. In Taiwan, the possibility of the ROC retaking mainland China became increasingly remote in the 1970s, particularly after the ROC's expulsion from the United Nations in 1971, the establishment of diplomatic relations between the PRC and United States in 1979, and Chiang Kai-shek's death in 1975.[20]

Majority rule in Taiwan

[edit]With the end of authoritarian rule in the 1980s, there was a shift in power within the KMT away from the faction who had accompanied Chiang to Taiwan. Taiwanese who grew up under Japanese rule, which accounted for more than 85% of the population, gained more influence and the KMT began to move away from its ideology of cross-strait unification. After the exposure of 1987 Lieyu massacre in June, martial law was finally lifted in Taiwan on 15 July 1987. Following the Wild Lily student movement, President Lee Teng-hui announced in 1991 that his government no longer disputed the rule of the CCP in China, leading to semi-official peace talks (leading to what would be termed as the "1992 Consensus") between the two sides. The PRC broke off these talks in 1999 when President Lee described relations with the PRC as "Special state-to-state relations".

Until the mid-1990s, unification supporters on Taiwan were bitterly opposed to the CCP. Since the mid-1990s a considerable warming of relations between the CCP and Taiwanese unification supporters, as both oppose the pro-Taiwan independence bloc. This brought about the accusation that unification supporters were attempting to sell out Taiwan. They responded saying that closer ties with mainland China, especially economic ties, are in Taiwan's interest.

Rise of the Democratic Progressive Party

[edit]After the 2000 Taiwanese presidential election, which brought the independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party's candidate President Chen Shui-bian to power, the Kuomintang, faced with defections to the People First Party, expelled Lee Teng-hui and his supporters and reoriented the party towards unification. At the same time, the People's Republic of China shifted its efforts at unification away from military threats (which it de-emphasized but did not renounce) towards economic incentives designed to encourage Taiwanese businesses to invest in mainland China and aiming to create a pro-Beijing bloc within the Taiwanese electorate.

Within Taiwan, unification supporters tend to see "China" as a larger cultural entity divided by the Chinese Civil War into separate states or governments within the country. In addition, supporters see Taiwanese identity as one piece of a broader Chinese identity rather than as a separate cultural identity. However, supporters do oppose desinicization inherent in Communist ideology such as that seen during the Cultural Revolution, along with the effort to emphasize a Taiwanese identity as separate from a Chinese one. As of the 2008 election of President Ma Ying-jeou, the KMT agreed to the One China principle, but defined it as led by the Republic of China rather than the People's Republic of China.

Military operations

[edit]Military clashes between the two sides include the First, Second and Third Taiwan Strait Crisis.

One China, Two Systems proposal

[edit]

Deng Xiaoping developed the principle of one country, two systems in relation to Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.[23]: 176 According to the 1995 proposal outlined by CCP General Secretary and paramount leader Jiang Zemin, Taiwan would lose sovereignty and the right to self-determination, but would keep its armed forces and send a representative to be the "number two leader" in the PRC central government. Thus, under this proposal, the Republic of China would become fully defunct.[citation needed]

In May 1998, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party convened a Work Conference on Taiwan Affairs which stated that the whole party and the whole nation should work together for peaceful unification.[24]: 11

Few Taiwanese are in support of the One Country, Two Systems policy while some unification supporters argued to uphold the status quo until mainland China democratized and industrialized to the same level as Taiwan. In the 2000 presidential election, independent candidate James Soong proposed a European Union-style relation with mainland China (this was echoed by Hsu Hsin-liang in 2004) along with a non-aggression pact. In the 2004 presidential election, Lien Chan proposed a confederation-style relationship. Beijing objected to the plan, claiming that Taiwan was already part of China, and was not a state and, as such, could not form a confederation with it. Developments in Hong Kong have caused the population of Taiwan in recent years to find "One China, Two Systems" to be "unpersuasive, unappealing, and even untrustworthy."[25]

Stasis

[edit]Unification proposals were not actively floated in Taiwan and the issue remained moot under President Chen Shui-bian, who refused to accept talks under Beijing's pre-conditions. Under the PRC administration of Hu Jintao, incorporating Taiwan lost emphasis amid the reality that the DPP presidency in Taiwan would be held by pro-independence President Chen until 2008. Instead, the emphasis shifted to meetings with politicians who opposed independence.[citation needed]

A series of high-profile visits in 2005 to China by the leaders of the three pan-Blue Coalition parties was seen as an implicit recognition of the status quo by the PRC government. Notably, Kuomintang chairman Lien Chan's trip was marked by unedited coverage of his speeches and tours (and some added positive commentary) by government-controlled media and meetings with high level officials including Hu Jintao. Similar treatment (though marked with less historical significance and media attention) was given during subsequent visits by PFP chairman James Soong and New Party chairman Yok Mu-ming. The CCP and the Pan-Blue Coalition parties emphasized their common ground in renewed negotiations under the 1992 consensus, opening the Three Links, and opposing Taiwan's formal independence.[citation needed]

The PRC passed an Anti-Secession Law shortly before Lien's trip. While the Pan-Green Coalition held mass rallies to protest the codification of using military force to retake Taiwan, the Pan-Blue Coalition was largely silent. The language of the Anti-Secession Law was clearly directed at the independence supporters in Taiwan (termed "'Taiwan independence' secessionist forces" in the law) and designed to be somewhat acceptable to the Pan-Blue Coalition. It did not explicitly declare Taiwan to be part of the People's Republic of China but instead used the term "China" on its own, allowing definitional flexibility. It made repeated emphasis of promoting peaceful national unification but left out the concept of "one country, two systems" and called for negotiations in "steps and phases and with flexible and varied modalities" in recognition of the concept of eventual rather than immediate incorporation of Taiwan.[citation needed]

Under both President Chen and President Ma Ying-jeou, the main political changes in cross-straits relationship involved closer economic ties and increased business and personal travel. Such initiatives were met by grassroots oppositions such as the Sunflower Student Movement, which successfully scuttled Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement in 2014. President Ma Ying-Jeou advocated for the revitalization of Chinese culture, as in the re-introduction of traditional Chinese in texts to mainland China used in Taiwan and historically in China. It expressed willingness to allow the usage simplified Chinese in informal writing.[citation needed]

Starting in 2017, the All-China Federation of Taiwan Compatriots, a group of Taiwanese residing in the PRC, took on a more prominent role in the CCP's united front efforts directed at Taiwan.[26]

Official stance of the People's Republic of China

[edit]The CCP uses the phrase "reunification" instead of "unification" to emphasize its assertion that the island of Taiwan has always belonged to China, or at least that the island Taiwan has been part of China for a long period of time, and that it currently belongs to People's Republic of China, but is currently being sporadically occupied by alleged separatists who support Taiwanese independence.[27]

“Liberation of Taiwan” is a term used in the PRC to garner public opinion for cross-strait unification with the Republic of China in Taiwan, proposing the use of military force to achieve it. In 1956, Mao Zedong first introduced the term, which was construed to mean a "peaceful" way to unify with the Republic of China. Despite this, both governments have had numerous long-term military confrontations. The CCP has set the unification of China as the most important political goal since the founding of the PRC.[28]

In January 1979, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress issued its first appeal to the KMT, which marked the start of the PRC's "peaceful reunification" strategy.[29] In March 2005, the 10th National People's Congress passed the Anti-Secession Law authorizing military force for unification.[30] In 2019, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping proposed "peaceful reunification" based on the one country, two systems program. The government of the ROC led by President Tsai Ing-wen rejected the proposal.[31]

The PRC does not consider the ROC a sovereign state today, instead believing itself to be the ROC's successor after the PRC's founding in 1949.[32][33]

In 2024, the Chinese government issued a directive to the courts stating that "diehard" separatists could be tried in absentia with capital punishment imposed.[34][35]

Taiwan and Penghu

[edit]Officially, the PRC traces Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan Island, allegedly historically known by the Chinese as "Liuqiu" (which is closely related to the name of the modern Japanese Ryukyu Islands), back to roughly around the 3rd century CE (specifically the year 230 CE).[36] However, most Western sources trace Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan Island back to either 1661–1662 CE (the year(s) when Koxinga established the Kingdom of Tungning in southwestern Taiwan) or 1683 CE (the year when the Qing dynasty absorbed the Kingdom of Tungning into its territory and subsequently lay claim to the entire island).[37]

Official stance of the Republic of China

[edit]Politics in the Republic of China are divided into two main camps, the Pan-Blue and the Pan-Green Coalitions. The former camp is characterized by general Chinese nationalism and ROC nationalism, whereas the latter camp is characterized by Taiwanese nationalism.[citation needed]

ROC official sources note that Qing forces occupied the island of Taiwan's western and northern coasts from 1683, and that Taiwan was declared a Qing province in 1885.[38]

Pan-Blue interpretation

[edit]The Japanese Instrument of Surrender (1945) is seen by the Pan-Blue camp as legitimizing the Chinese claims of sovereignty over Taiwan Island which were made with the 1943 Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Declaration (1945).[39] The common Pan-Blue view asserts that Taiwan Island was returned to China in 1945. Irredentist in nature, those who possess this view commonly perceive Retrocession Day to be the conclusion to a continuous saga of reunification struggles on both sides of the strait, lasting from 1895, the year that Taiwan Island was ceded to Japan, up until 1945, the end of the Second World War. Hence, there is a common view among the Pan-Blue camp that the island of Taiwan was always a Chinese territory under Japanese occupation and never belonged to Japan, neither legally nor in spirit. The Cairo Declaration, Potsdam Declaration, and Japanese Instrument of Surrender are seen as proofs that the Treaty of Shimonoseki was nullified in its entirety in 1945, hence proving that the island of Taiwan always rightfully belonged to China throughout those fifty years of reunification struggles. Shortly following these events, the island of Taiwan was split from mainland China again, according to the common Pan-Blue view, marking the beginning of another reunification saga. Still, the Pan-Blue camp considers both Taiwan and mainland China to be currently under Chinese rule, with the division between the island of Taiwan and mainland China merely being internal, rather than directly the result of outsider aggression; this view is demonstrated through the 1992 Consensus, which some allege to be an agreement reached between officials of both the Kuomintang and the CCP in 1992. The notion of 1992 Consensus is that there is One China and that the island of Taiwan is part of China, but that the legitimate government of China can be interpreted differently by the two sides of the strait.[citation needed]

RoC singer Teresa Teng performed in many countries around the world, but never in mainland China. During her 1980 TTV concert, when asked about such possibility, she responded by stating that the day she performs on the mainland will be the day the Three Principles of the People are implemented there – in reference to either the pursuit of Chinese democracy or reunification under the banner of the ROC.[40][41][42]

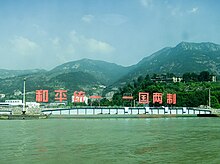

Kinmen has a prominent white wall with giant red characters "三民主義統一中國" meaning "Reunify China under the Three Principles of the People".[citation needed]

Pan-Green interpretation

[edit]The views of the Pan-Green camp, though they are diverse, tend to be characterized by Taiwanese nationalism. Hence, most within the Pan-Green camp are opposed to the idea of Taiwan being part of China. Still, most within the Pan-Green camp accept certain historical facts which suggest that Taiwan was part of China. The common Pan-Green view accepts that Taiwan was controlled by a regime in mainland China between 1683 and 1895, though many characterize this as a period of constant rebellion, or suppression of identity (or discovery of a new identity), or colonization by the foreign Manchu people. While most among the Pan-Green camp accept that the transition from Chinese to Japanese rule in 1895 was violent and tragic, many believe that rule under the Japanese was either more benevolent than rule under the Chinese (both KMT and Qing) or more productive. Hence, most Pan-Green do not support the notion that Taiwan was part of China between 1895 and 1945, and neither the notion that there was a strong Chinese unification sentiment in Taiwan at that time. "Dark Green" members of the Pan-Green camp generally do not believe that the Treaty of Shimonoseki was ever nullified. Certain sources claim that attempts were made to nullify the treaty, but that these attempts were either illegal or futile,[43] whereas other sources claim that the notion that the treaty was ever nullified is a complete fabrication by the KMT in modern times.[44]

Tibet and Outer Mongolia

[edit]The ROC has the historical claims to Tibet and Outer Mongolia.

The southwestern region of Tibet was governed by the Dalai Lama from 1912 to 1951 as a de facto independent state instead of the Ganden Phodrang. The ROC government has asserted that "Tibet was placed under the sovereignty of China" when the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) ended the brief Nepalese invasion (1788–1792) of parts of Tibet in c. 1793.[45] while the Tibetan Government in Exile asserts that Tibet was an independent state until the PRC invaded Tibet in 1949/1950.[46][47] By that point, the position of the Republic of China with regard to Tibet appeared to become more nuanced as was stated in the following opening speech to the International Symposium on Human Rights in Tibet on 8 September 2007 through the pro-Taiwan independence then ROC President Chen Shui-bian who stated that his offices no longer treated exiled Tibetans as Chinese mainlanders.[48] Today, the region is ruled by the PRC-governed Tibet Autonomous Region with parts of the ROC-claimed Xikang province.

In the northern region, Outer Mongolia, now controlled by the independent Mongolia and the Russian Republic of Tuva, it declared independence from the Qing dynasty in 1911 while China retained its control over the area and reasserted control over Outer Mongolia in 1919.[49][50] Consequently, Mongolia sought Soviet Russian support to reclaim its independence. In 1921, both Chinese and White Russian forces were driven out by the Red Army of the Soviet Union and pro-Soviet Mongolian forces. In 1924, the Mongolian People's Republic was formed.[49] Soviet pressure forced China to recognize the independence of Mongolia in 1946, but the ROC reasserted the claims to Outer Mongolia in 1953. However, the claim was dropped in 2002 as the ROC Ministry of Foreign Affairs opened a representative office in Mongolia in 2002 with reciprocity from Mongolia in the ROC in 2003.[51]

Public opinion

[edit]Republic of China in Taiwan

[edit]In 2019, 89% of Taiwanese opposed a 'One Country, Two Systems' unification with the PRC, more than double the opposition at the beginning of the millennium, when polls consistently found 30% to 40% of all residents were opposed, even with more preferential treatments.[52] At that time the majority supported so-called "status quo now".[53][54] While dominating international focus on Taiwanese politics, unification is generally not the deciding issue in Taiwanese political campaigns and elections.[55] A majority of the population supports the status quo, mostly in order to avoid a military confrontation with PRC, but a sizable proportion supports a name rectification campaign.[56]

Opponents of "One Country, Two Systems" cite its implementation in Hong Kong, where despite promises of high levels of autonomy, the PRC government has gradually increased its control of Hong Kong through restricting elections and increasing control over media and policy.[57] The National Security Law and the related crackdowns further diminished Taiwanese support for such a system.[25]

The Taiwanese pro-unification minority has at times been vocal in media and politics. For the 2004 presidential election the unification question gained some attention as different political parties were discussing the issue. A series of demonstrations, some of which were organized by pro-unification minorities, gained significant attention.[58]

Since 2008, polls have consistently found a majority of Taiwanese residents identify as "Taiwanese" rather than "Chinese" or "both."[59]

People's Republic of China

[edit]A 2019 phone survey conducted in nine major cities found that 53.1% of respondents supported military force for unification (武统; wu tong) with Taiwan while 39.1% stated that they would oppose military force for unification under any circumstance.[60]: 37 [61]: 62 The study concluded that education level and unfavorable views of the Taiwan government were the greatest predictors of support for military force for unification.[61]: 46 Politically, economically, and socially privileged respondents, as well as respondents with greater understandings of Taiwan, were also more likely to support military force for unification.[61]: 46 Residents of Xiamen and Guangzhou (on the coast) were less likely to support military force.[61]: 46

A 2020-2021 national public opinion poll conducted in China by academics Adam Y. Liu and Xiaojun Li analyzed public approval for a range of policies, including military force for unification, limited warfare in offshore islands, economic sanctions, maintaining the status quo, and de facto Taiwan independence.[60]: 33–34 The resulting study, published in 2023 in the Journal of Contemporary China, concludes that 55% of respondents support using military force for unification, although that amount was not greater than various less aggressive policy options.[62][63][60]: 34 Approximately one-third of respondents were explicitly opposed to military force for unification.[60]: 45 Respondents with college degrees or more advanced degrees were more likely to endorse the more aggressive policy options.[60]: 43

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Callick, Rowan (11 March 2007). "China's great firewall". The Australian. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Hoffman, Samantha; Mattis, Peter (18 July 2016). "Managing the Power Within: China's State Security Commission". War on the Rocks. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Robinson, Dan (16 March 2005). "US House Criticizes China Bill on Taiwan Secession". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 2 April 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2005.

- ^ "政治大學 選舉研究中心". Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Taiwan (Republic of China)'s Constitution of 1947 with Amendments through 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ 民進黨:台灣是主權獨立國家 叫中華民國 | 政治 | 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "China threatens death penalty for 'diehard' Taiwan separatists". Reuters. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "China threatens death penalty for supporters of Taiwan independence". Radio Free Asia. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "U.S.-China Relations". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Tao, Xie. "The Politics of History in China-Japan Relations". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Message to Compatriots in Taiwan". China.org.cn. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ 1981年9月30日 叶剑英进一步阐明关于台湾回归祖国,实现和平统一的9条方针政策--中国共产党新闻--中国共产党新闻网. cpc.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ ""One country, two systems" best institutional guarantee for HK, Macao prosperity, stability: Xi". Beijing: Xinhua. 18 October 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "A policy of "one country, two systems" on Taiwan". www.mfa.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "Taiwan's president rejects 'one country, two systems' deal with China". France 24. 20 May 2020. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ a b Franklin., Copper, John (2007). Historical dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China) (3rd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 9780810856004. OCLC 71288776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stéphane, Corcuff (2016). Memories of the Future: National Identity Issues and the Search for a New Taiwan. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780765607911. OCLC 959428520.

- ^ Hsiao, Frank S. T.; Sullivan, Lawrence R. (1979). "The Chinese Communist Party and the Status of Taiwan, 1928-1943". Pacific Affairs. 52 (3): 446. doi:10.2307/2757657. JSTOR 2757657.

- ^ van der Wees, Gerrit (3 May 2022). "When the CCP Thought Taiwan Should Be Independent". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b W., Hughes, Christopher (1997). Taiwan and Chinese nationalism : national identity and status in international society. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780203444191. OCLC 52630115.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldstein, Steven (2000). The United States and the Republic of China, 1949–1978: Suspicious Allies. Asia/Pacific Research Center. pp. 16–20. ISBN 9780965393591.

- ^ "TaiwanHeadlines – Home – Mail bomb explodes in Taipei office". 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Hu, Richard (2023). Reinventing the Chinese City. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21101-7.

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng (2024). "Is Beijing's Long Game on Taiwan about to End? Peaceful Unification, Brinksmanship, and Military Takeover". In Zhao, Suisheng (ed.). The Taiwan Question in Xi Jinping's Era: Beijing's Evolving Taiwan Policy and Taiwan's Internal and External Dynamics. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003521709. ISBN 9781032861661.

- ^ a b Chong, Ja Ian (20 February 2023). "The Many "One Chinas": Multiple Approaches to Taiwan and China". Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Civilian group from mainland China to take more prominent role in cross-strait affairs". South China Morning Post. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Wang, Amber (7 July 2022). "China puts Taiwan 'reunification' effort at heart of national revival plans". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Dorothy Perkins (2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Hsiao, Russell (12 January 2009). "Hu Jintao's 'Six-Points' Proposition to Taiwan". Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Bellows, Thomas J. (December 2005). "The anti-secession law, framing, and political change in Taiwan". Asian Journal of Political Science. 13 (2): 103–123. doi:10.1080/02185370508434260. ISSN 0218-5377.

- ^ Horton, Chris (5 January 2019). "Taiwan's President, Defying Xi Jinping, Calls Unification Offer 'Impossible'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Bush, Richard C. (24 January 2013). "Thoughts on the Republic of China and its Significance". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "White Paper: The Taiwan Question and China's Reunification in the New Era (Full Text)". munich.china-consulate.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "China threatens death penalty for 'diehard' Taiwan separatists". Reuters. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "China threatens death penalty for supporters of Taiwan independence". Radio Free Asia. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "What is the reason for saying "Taiwan is an inalienable part of China"?". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "China and Taiwan: A really simple guide". BBC News. 12 January 2022. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Affairs, Ministry of Foreign (11 June 2019). "History of Taiwan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Huang, Eric (1 August 2015). "Taiwan's Opposition Must Get Clear on the Country's Sovereignty". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ 鄧麗君國父紀念館演唱會 1980年10月4日 (Video file) (published 13 January 2016). 4 October 1980. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "PHOTO ESSAYS Teresa Teng's heavenly voice continues to echo transcendently". Central News Agency (Taiwan). 5 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "鄧麗君逝世20週年 追憶天使美聲". www.cna.com.tw. Central News Agency (Taiwan). Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Treaty of Shimonoseki". Taiwan Civil Society. 22 March 2012. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Goah, Kengchi (11 September 2005). "A lie told a thousand times". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Sperling (2004) pp.6,7. Goldstein (1989) p.72. Both cite the ROC's position paper at the 1914 Simla Conference.

- ^ Sperling (2004) p.21

- ^ "Five Point Peace Plan". The Dalai Lama. 21 September 1987. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ 'President Chen Shui-bian's Remarks at the Opening Ceremony of the 2007 International Symposium on Human Rights in Tibet' Sep 8, 2007 [dead link]

- ^ a b "China-Mongolia Boundary" (PDF). International Boundary Study (173). The Geographer, Bureau of Intelligence and Research: 2–6. August 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2006. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "Chinese Look To Their Neighbors For New Opportunities To Trade". International Herald Tribune. 4 August 1998. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ "代表處簡介 – 代表處簡介 – 駐蒙古代表處". Taipei Trade and Economic Representative Office in Ulaanbaatar. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Mainland Affairs Council: MAC Press Release No. 94 (2019). "Growing Majority in Taiwan Reject the CCP's "One Country, Two Systems" and Oppose Beijing's Military and Diplomatic Suppression". Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mainland Affairs Council-How Taiwan People View Cross-Strait Relations (2000–02)". Mainland Affairs Council. 22 March 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ Flannery, Russell (6 September 1999). "Taiwan Poll Reflects Dissatisfaction With China's Unification Formula". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ Diplomat, Euhwa Tran, The. "Taiwan's 2016 Elections: It's Not About China". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yu, Ching-hsin (15 March 2017). "The centrality of maintaining the status quo in Taiwan elections". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Beijing's crackdown on Hong Kong is alienating Taiwan- Nikkei Asian Review". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ Corcuff, Stéphane (1 May 2004). "The Supporters of Unification and the Taiwanisation Movement". China Perspectives. 2004 (3). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.2942. ISSN 2070-3449.

- ^ "Election Study Center, NCCU-Taiwanese / Chinese Identity". esc.nccu.edu.tw (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Liu, Adam Y.; Li, Xiaojun (2024). "Assessing Public Support for (Non-)Peaceful Unification with Taiwan: Evidence from a Nationwide Survey in China". In Zhao, Suisheng (ed.). The Taiwan Question in Xi Jinping's Era: Beijing's Evolving Taiwan Policy and Taiwan's Internal and External Dynamics. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781032861661.

- ^ a b c d Qi, Dongtao; Zhang, Suixin; Lin, Shengqiao (2024). "Urban Chinese Support for Armed Unification with Taiwan: Social Status, National Pride, and Understanding of Taiwan". In Zhao, Suisheng (ed.). The Taiwan Question in Xi Jinping's Era: Beijing's Evolving Taiwan Policy and Taiwan's Internal and External Dynamics. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781032861661.

- ^ Tang, Kelly (17 January 2024). "China's Nationalists Urge War to Reunify Taiwan After Presidential Election". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Liu, Adam Y.; Li, Xiaojun (14 May 2023). "Assessing Public Support for (Non)Peaceful Unification with Taiwan: Evidence from a Nationwide Survey in China". Journal of Contemporary China. 33 (145): 1–13. doi:10.1080/10670564.2023.2209524. ISSN 1067-0564.

Further reading

[edit]- Bush, Richard C.; O'Hanlon, Michael E. (30 March 2007). A War Like No Other: The Truth About China's Challenge to America. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-98677-5.

- Bush, R (2006). Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1290-1.

- Carpenter, T. (2006). America's Coming War with China: A Collision Course over Taiwan. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6841-1.

- Cole, B. (2006). Taiwan's Security: History and Prospects. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36581-3.

- Copper, J. (2006). Playing with Fire: The Looming War with China over Taiwan. Praeger Security International General Interest. ISBN 0-275-98888-0.

- Federation of American Scientists; et al. (2006). "Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists.

- Gill, B (2007). Rising Star: China's New Security Diplomacy. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-3146-7.

- Shirk, S. (2007). China: Fragile Superpower: How China's Internal Politics Could Derail Its Peaceful Rise. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530609-5.

- Tsang, S. (2006). If China Attacks Taiwan: Military Strategy, Politics and Economics. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40785-0.

- Tucker, N.B. (2005). Dangerous Strait: the U.S.-Taiwan-China Crisis. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13564-5.