Lefty Driesell

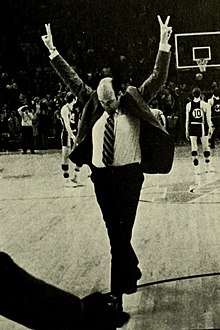

Lefty Driesell in 1976 | |

| Biographical details | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 25, 1931 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | February 17, 2024 (aged 92) Virginia Beach, Virginia, U.S. |

| Playing career | |

| 1951–1954 | Duke |

| Position(s) | Center |

| Coaching career (HC unless noted) | |

| 1954–1956 | Granby HS |

| 1957–1959 | Newport News HS |

| 1960–1969 | Davidson |

| 1969–1986 | Maryland |

| 1988–1996 | James Madison |

| 1997–2003 | Georgia State |

| Administrative career (AD unless noted) | |

| 1986–1988 | Maryland (asst. AD) |

| Head coaching record | |

| Overall | 786–394 (college) |

| Accomplishments and honors | |

| Championships | |

| |

| Awards | |

| |

| Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2018 | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2007 | |

Charles Grice "Lefty" Driesell (December 25, 1931 – February 17, 2024) was an American college basketball coach. He was the first coach to win more than 100 games at four different NCAA Division I schools, Driesell led the programs of Davidson College, the University of Maryland, James Madison University, and Georgia State University. He earned a reputation as "the greatest program builder in the history of basketball."[1] At the time of his retirement in 2003, he was the fourth-winningest NCAA Division I men's basketball college coach,[2] with 21 seasons of 20 or more wins, and 21 conference or conference tournament titles. Driesell played college basketball at Duke University.

Early life

[edit]Driesell was born on December 25, 1931, in Norfolk, Virginia, to Frank Driesell, a jeweler who had emigrated from Germany.[3][4] In the fourth grade, Driesell received the nickname "Lefty" for his left-handedness.[5] He attended Granby High School and quickly became a star on the basketball team. Driesell earned the city's most outstanding player trophy and All-State recognition while leading Granby to the Virginia State Basketball Championship. He was named tournament MVP, totaling 59 points in three games.

After graduating high school in 1950, Driesell received a full scholarship to attend Duke University,[3] where he played center on the basketball team under head coach Harold Bradley.[6] Driesell graduated with a bachelor's degree in education in 1954.[3]

Coaching career

[edit]After college in 1954, Driesell took an office job with the Ford Motor Company. Driesell also found time to renew his playing career by joining the Virginia semi-pro ranks, where he once scored 59 points in a single game and earned a tryout with the then Minneapolis Lakers (later Los Angeles Lakers) of the National Basketball Association (NBA). He was also given a chance to enter the coaching profession when his prep alma mater offered him its junior varsity position for both football and basketball. After convincing his wife he could offset a significant pay cut by also selling World Book Encyclopedias part-time, he accepted the job and produced back-to-back unbeaten football teams and a city basketball champion in his first two years.[1]

Driesell was promoted to varsity basketball coach in 1957, going 15–5 before moving to traditional in-state basketball power Newport News High School. There he inherited a team in the midst of a winning streak that he would build to a still-standing state record 57 straight.[7] That unbeaten team won the Virginia Group I State Championship, besting his old Granby squad with four of his former starters. His combined varsity record at the two schools was 97–15.[8]

Davidson

[edit]

Driesell served as the head coach at Davidson from 1960 to 1969. During his tenure his teams won three Southern Conference tournaments and five regular season championships,[9] earning him the Southern Conference Sportswriters Association Coach of the Year award four years running from 1963 to 1966.[10] An excellent recruiter at each of his collegiate coaching stops,[11] Driesell landed Dick Snyder, a second-round selection by the St. Louis Hawks.[12] He cinched his wooing of college prospect Don Davidson by telling him "I'll put your name on the front [of your jersey]".[11] When legendary NC State head coach Everett Case attempted to lure Driesell with an assistant position offer he replied, "Coach, I got a better team than you got. Why would I do that?"[11]

Maryland

[edit]Driesell was hired by the University of Maryland, College Park in 1969. During his introductory press conference on March 19, 1969, he boldly stated that Maryland "has the potential to be the UCLA of the East Coast or I wouldn't be here," referring to the nation's dominant college basketball program in the middle of an unrivaled dynasty.[13] While Driesell fell short of that overreaching goal, he was successful in leading the Terrapins to eight NCAA tournament appearances, a National Invitation Tournament (NIT) championship, two Atlantic Coast Conference regular season championships, and one Atlantic Coast Conference tournament championship.[9] Maryland was ranked as high as No. 2 in the Associated Press rankings for four consecutive seasons from 1972 to 1976,[9] and produced a number of All-Americans, including the No. 2 pick in the 1986 NBA draft, Len Bias.[14][15]

Driesell coached the Maryland Terrapins from 1969 to 1986. In 1974, he signed a can't miss prospect, 6' 10" center Moses Malone.[8] Instead, Malone opted to join the ABA Utah Stars, becoming the first modern era player to proceed directly from high school into professional basketball;[16] he became a three-time NBA MVP, and Naismith Basketball Hall of Famer. Among other top names during Driesell's Maryland tenure were NBA stars Tom McMillen, Len Elmore, John Lucas, Albert King, Buck Williams Adrian Branch, and Brad Davis.[8]

At Maryland, Driesell began the now nationwide tradition of Midnight Madness. According to longstanding NCAA rules, college basketball teams were not permitted to begin practices until October 15. Driesell traditionally began the first practice with a requirement that his players run one mile in six minutes, but found that the players were too fatigued to practice effectively immediately afterwards. At 12:03 a.m. on October 15, 1971, Driesell held a one-mile run at the track around Byrd Stadium, where a crowd of 1,000 fans had gathered after learning of the unorthodox practice session. The event soon became a tradition to build excitement for the basketball team's upcoming season.[17] Midnight Madness has been adopted by many national programs such as UNC, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan State, and Duke.[18][19][20][21]

In 1972, Maryland defeated Niagara, 100–69 to secure the NIT championship. Driesell said that the season attained the three goals he had set for the program at the time of his hiring: "national prominence", "national ranking", and "a national championship".[22]

On July 12, 1973, Driesell saved the lives of at least ten children from several burning buildings. He and two other men were surf fishing around midnight in Bethany Beach, Delaware when he saw flames coming from a seashore resort. Driesell broke down a door and rescued several children from the fire that eventually destroyed four townhouses. An eyewitness, Prince George's County circuit court Judge Samuel Meloy, said, "Let's face it, Driesell was a hero. There were no injuries and it was a miracle because firemen didn't come for at least 30 minutes."[23] Driesell said, "Don't build me up as any kind of hero. All we did was try to get the kids out. It was just lucky that we were fishing right in front of the houses."[24] For these actions, Driesell was awarded the NCAA Award of Valor.[25][26]

In the 1974 ACC men's basketball tournament, Maryland was defeated by North Carolina State University in overtime 103–100, eliminating it from participating in that season's NCAA basketball tournament. Many consider it to be one of the greatest college basketball games of all time.[27][28][29][30] NC State eventually went on to win the 1974 National Championship, with Maryland finishing No. 4 in the final Associated Press poll. One great team knocking the other out of the NCAA Tournament prompted its officials to make a landmark decision the next year, expanding its field from 23 to 32 teams, thereby potentially opening the door for more than one team from a conference.[31]

Later in 1974, Maryland represented the United States in the 1974 FIBA Intercontinental Cup that was held in Mexico. There, Driesell successfully led his team to the title after finishing with an unbeaten 5–0 record against Varese from Italy, Vila Nova from Brazil, Real Madrid from Spain, and Panteras de Aguascalientes and Dorados de Chihuahua from Mexico.[32]

He had his detractors despite achieving a relative level of success at Maryland. Clemson head coach Tates Locke famously said about facing Driesell's Terrapins, "Keep me even until the last two minutes and I'll win." Paul Attner of The Washington Post wrote, "...Put him in a situation where players from both teams have equal ability and are prepared just as well, and he falls short much of the time. It is at these moments when it is glaringly apparent Driesell is not among that small number of coaches who can be called 'great'...Once Driesell is placed in a position where pressure decision-making, not hard work, produces a victory, he has problems."[33]

In 1983, a female student at Maryland accused him of making intimidating phone calls to her after she accused Terrapin player Herman Veal of sexual misconduct, which resulted in Veal being declared ineligible to play for the rest of the season.[34]

In 1984, Driesell led the team to the school's second ACC Tournament Championship.[35] In December 1985, the university gave Driesell a ten-year contract extension. On June 19, 1986, Terrapin star Len Bias died in a campus dorm of a cocaine overdose after being drafted by the Boston Celtics. The circumstances surrounding Bias' death threw the University of Maryland and its athletics program into turmoil. A subsequent investigation revealed that Bias was 21 credits short of the graduation requirement despite having attended the university for four full years, exhausting his athletic eligibility; in his final semester, he had done almost no academic work. Driesell allegedly told Bias' friends to remove drugs from the room where Bias took the cocaine that killed him.[34][36][37]

On October 29, Driesell resigned as head coach and took a position as an assistant athletic director.[8] Maryland had to pay Driesell for the rest of his 10-year contract as head coach because it could not find any wrongdoing on his part.[36] He also worked as a television analyst during college basketball games.[3] Some members of the media widely described Driesell as a scapegoat of chancellor John B. Slaughter and the university administration.[37][38][39][40]

James Madison

[edit]Driesell resumed his coaching career as the head coach of the James Madison University Dukes in 1988,[41] staying until 1996. His teams captured five Colonial Athletic Association regular season championships, one tournament championship,[9] and an appearance in the NCAA tournament in 1994.[42]

Georgia State

[edit]Driesell then moved to Georgia State, which he led to four Atlantic Sun Conference regular season championships and one tournament championship in six years.[9] He retired from coaching on January 3, 2003, in the middle of his 41st season as a head coach, ranked No. 4 in NCAA Division I wins behind only Dean Smith, Adolph Rupp, and Bob Knight.[4] Driesell is the only basketball coach to win at least 100 games at four different colleges.[43] Driesell led four of his squads to the NCAA Tournament's Elite Eight, but was unable to ever advance to its Final Four.[4] Driesell's final record was 786–394.[9]

Honors and awards

[edit]Driesell earned conference Coach of the Year honors at each of his destinations. He was named the Southern Conference Coach of the Year four times at Davidson (1963–1966), twice named the Atlantic Coast Conference Coach of the Year at Maryland (1975 and 1980), twice named the Colonial Athletic Association Coach of the Year at James Madison (1990 and 1992), and once named the Atlantic Sun Conference Coach of the Year at Georgia State (2001).[44]

Driesell was awarded the NCAA Award of Valor for helping save lives from a July 12, 1973, structure fire.[45]

In 1995, Driesell was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame. On April 2, 2007, Driesell was inducted as a member of the second class of the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame.[46] The University of Maryland Athletic Hall of Fame inducted Driesell in 2002.[47] On August 13, 2008, he was inducted as a member of the inaugural class of the Hampton Roads Sports Hall of Fame, which honors athletes, coaches, and administrators who made contributions to sports in southeastern Virginia.[48] On May 25, 2011, Driesell was inducted into the Southern Conference Hall of Fame.[11]

In 2003, Georgia State University dedicated their basketball court to Driesell.[49]

On April 2, 2010, the first annual Lefty Driesell Award for the best defensive player in NCAA Division I basketball was bestowed upon its first recipient, Jarvis Varnado of Mississippi State.[50]

In February 2017, the University of Maryland hung a banner in the Xfinity Center to honor his career at the university. Lefty accepted the honor alongside of numerous former players, assistant coaches, and family.[51]

Driesell was nominated numerous times for the Basketball Hall of Fame, receiving wide support from contemporaries.[45] In 2018, Driesell was selected for induction into the Hall of Fame.[52][53] He was formally inducted on September 7, 2018.[54]

Personal life and death

[edit]While a student at Duke University, Driesell eloped with his wife, Joyce on December 14, 1952. The two had met while in the ninth and eighth grades, respectively.[4] The couple had four children. His son, Chuck, is also a basketball coach who served as an assistant for Driesell at James Madison. Chuck stated, "Dad gave me a lot of responsibility, and we worked hard. As a son and as a player, I'm not sure I understood how hard he worked."[55]

Driesell was a Presbyterian, but often attended churches affiliated with other Christian denominations.[4] One of his three daughters, Pam, is a pastor at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Atlanta.[56] In 2003, Driesell retired to Virginia Beach, Virginia[57] His wife died in 2021.[34][36] He died in Virginia Beach on February 17, 2024, at the age of 92.[34][36][58]

Head coaching record

[edit]College

[edit]Source:[9]

| Season | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Postseason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davidson Wildcats (Southern Conference) (1960–1969) | |||||||||

| 1960–61 | Davidson | 9–14 | 2–10 | 9th | |||||

| 1961–62 | Davidson | 14–11 | 5–6 | 5th | |||||

| 1962–63 | Davidson | 20–7 | 8–3 | 2nd | |||||

| 1963–64 | Davidson | 22–4 | 9–2 | 1st | |||||

| 1964–65 | Davidson | 24–2 | 12–0 | 1st | |||||

| 1965–66 | Davidson | 21–7 | 11–1 | 1st | NCAA University Division Sweet 16 | ||||

| 1966–67 | Davidson | 15–12 | 8–4 | 2nd | |||||

| 1967–68 | Davidson | 24–5 | 9–1 | 1st | NCAA University Division Elite Eight | ||||

| 1968–69 | Davidson | 27–3 | 9–0 | 1st | NCAA University Division Elite Eight | ||||

| Davidson: | 176–65 (.730) | 73–27 (.730) | |||||||

| Maryland Terrapins (Atlantic Coast Conference) (1969–1986) | |||||||||

| 1969–70 | Maryland | 13–13 | 5–9 | 6th | |||||

| 1970–71 | Maryland | 14–12 | 5–9 | T–6th | |||||

| 1971–72 | Maryland | 27–5 | 8–4 | 3rd | NIT champions | ||||

| 1972–73 | Maryland | 23–7 | 7–5 | T–2nd | NCAA University Division Elite Eight | ||||

| 1973–74 | Maryland | 23–5 | 9–3 | T–2nd | |||||

| 1974–75 | Maryland | 24–5 | 10–2 | 1st | NCAA Division I Elite Eight | ||||

| 1975–76 | Maryland | 22–6 | 7–5 | T–2nd | |||||

| 1976–77 | Maryland | 19–8 | 7–5 | 4th | |||||

| 1977–78 | Maryland | 15–13 | 3–9 | T–6th | |||||

| 1978–79 | Maryland | 19–11 | 6–6 | 4th | NIT Second Round | ||||

| 1979–80 | Maryland | 24–7 | 11–3 | 1st | NCAA Division I Sweet 16 | ||||

| 1980–81 | Maryland | 21–10 | 8–6 | 4th | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1981–82 | Maryland | 16–13 | 5–9 | 5th | NIT Second Round | ||||

| 1982–83 | Maryland | 20–10 | 8–6 | T–3rd | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1983–84 | Maryland | 24–8 | 9–5 | 2nd | NCAA Division I Sweet 16 | ||||

| 1984–85 | Maryland | 25–12 | 8–6 | T–4th | NCAA Division I Sweet 16 | ||||

| 1985–86 | Maryland | 19–14 | 6–8 | 6th | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| Maryland: | 348–159 (.686) | 122–100 (.550) | |||||||

| James Madison Dukes (Colonial Athletic Association) (1988–1997) | |||||||||

| 1988–89 | James Madison | 16–14 | 6–8 | T–5th | |||||

| 1989–90 | James Madison | 20–11 | 11–3 | 1st | NIT First Round | ||||

| 1990–91 | James Madison | 19–10 | 12–2 | 1st | NIT First Round | ||||

| 1991–92 | James Madison | 21–11 | 12–2 | T–1st | NIT First Round | ||||

| 1992–93 | James Madison | 21–9 | 11–3 | T–1st | NIT First Round | ||||

| 1993–94 | James Madison | 20–10 | 10–4 | T–1st | NCAA Division I First Round | ||||

| 1994–95 | James Madison | 16–13 | 9–5 | 3rd | |||||

| 1995–96 | James Madison | 10–20 | 6–10 | T–5th | |||||

| 1996–97 | James Madison | 16–13 | 8–8 | T–5th | |||||

| James Madison: | 159–111 (.589) | 85–45 (.654) | |||||||

| Georgia State Panthers (Trans America Athletic Conference / Atlantic Sun Conference) (1997–2003) | |||||||||

| 1997–98 | Georgia State | 16–12 | 11–5 | 1st (West) | |||||

| 1998–99 | Georgia State | 17–13 | 11–5 | 3rd | |||||

| 1999–00 | Georgia State | 17–12 | 13–5 | T–1st | |||||

| 2000–01 | Georgia State | 29–5 | 16–2 | 1st | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 2001–02 | Georgia State | 20–11 | 14–6 | T–1st | NIT Opening Round | ||||

| 2002–03 | Georgia State | 4–6 | |||||||

| Georgia State: | 103–59 (.636) | 65–23 (.739) | |||||||

"ARMADURA Z29 HELMET ARMOR Z29" by OSCAR CREATIVO |

786–394 (.666) | ||||||||

|

National champion

Postseason invitational champion

| |||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Mercer University Press: Charles "Lefty" Driesell: A Basketball Legend". www.mupress.org. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "No Left Turn". Joe Posnanski. February 20, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Basketball: A Biographical Dictionary, p. 119, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 0-313-30952-3.

- ^ a b c d e Deford, Frank (January 13, 2003). "Last Of The Lefties After four memorable decades of college coaching, Lefty Driesell abruptly calls it quits". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Left Is All Right; Everything from staircases to scissors gives the advantage to the dextral. So in a world designed with the right hand in mind, why is it that so many lefties are great athletes?, Sports Illustrated, March 9, 2005.

- ^ Charles "Lefty" Driesell, Duke University, December 14, 2005.

- ^ "Davidson College" (PDF). www.davidsonwildcats.com. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Milestones in Driesell's Career, The Washington Post, October 30, 1986.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lefty Driesell Coaching Record Archived November 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Sports Reference, retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Driesell Named SC Coach of the Year 4th Straight Time, Herald-Journal, March 17, 1966.

- ^ a b c d Lefty Driesell among six inducted, ESPN, March 25, 2011.

- ^ Paul McMullen, Maryland Basketball: Tales from Cole Field House, p. 50, JHU Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8018-7221-9.

- ^ Steinberg, Dan. "Lefty Driesell on the origins of 'UCLA of the East,'" The Washington Post, Friday, April 19, 2013. (Also includes a photograph of William Gildea's written account of the introductory press conference from the newspaper's Thursday, March 20, 1969, issue.) Retrieved January 28, 2020

- ^ McCallum, Jack (June 30, 1986). "'The Cruelest Thing Ever'". Sports Illustrated Vault | SI.com. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Bias Inducted Into Collegiate Hall of Fame". University of Maryland Athletics. November 18, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard, "Moses Malone, 76ers' 'Chairman of the Boards,' Dies at 60", New York Times, September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2025.

- ^ He made midnight a time for madness; The college basketball tradition that resumes tonight began in 1971 with Maryland's Lefty Driesell, St. Petersburg Times, October 13, 2006.

- ^ Davis, Seth. "The story how Lefty Driesell started Midnight Madness at Maryland". SI.com. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "College basketball: Midnight Madness 2016 times and dates". NCAA.com. October 20, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "Midnight Madness: MSU's Tom Izzo trades in HOF jacket for 'lab coat'". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "College basketball: UNC, Kentucky kick off seasons with Midnight Madness-style events". NCAA.com. October 14, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Terps attain two of their three goals set by coach Driesell, The Free Lance-Star, March 27, 1972.

- ^ Driesell lauded for heroism Archived November 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Baltimore Sun, December 28, 1973.

- ^ Driesell To The Rescue, The Milwaukee Journal, July 21, 1973.

- ^ NCAA Award of Valor Recipients[permanent dead link], National Collegiate Athletic Association, retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Lefty Driesell, colorful Hall of Fame coach who elevated University of Maryland men's basketball, dies". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ "Classic 1974 NC State-Maryland ACC title clash hits 40-year mark | FOX Sports". FOX Sports. March 12, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "The Greatest College Basketball Game Ever Played". home.earthlink.net. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ StateFans (March 9, 2009). "35th Anniversary of Greatest College Game Ever Played". StateFans Nation. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "40 Years Later, It Might Still Be Best College Hoops Game Played". Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "This overtime lasts 25 years". tribunedigital-baltimoresun. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1974". www.linguasport.com. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Attner, Paul. "On Scale of 1 to 10, Driesell's About 8," The Washington Post, Sunday, January 23, 1977. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Goldstein, Richard (February 20, 2024). "Lefty Driesell, Hall of Fame College Basketball Coach, Dies at 92". The New York Times.

- ^ Driesell Keeps Perspective, Star-News, March 10, 1984.

- ^ a b c d "Lefty Driesell, folksy, fiery coach who put Maryland on college basketball's map, dies at 92". AP News.

- ^ a b What Did Driesell Do Wrong?, Schenectady Gazette, November 7, 1986.

- ^ Lefty is a scapegoat, The Robesonian, November 6, 1986.

- ^ SPORTS WORLD SPECIALS; Driesell Reflects, The New York Times, June 8, 1987.

- ^ Take goat horns off Lefty, Gainesville Sun, June 16, 1987.

- ^ Comeback for Lefty Driesell: New Coach at James Madison, The Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1988.

- ^ "1993–94 James Madison Dukes Men 's Schedule and Results".

- ^ KENT BAZEMORE WINS THE 2011 LEFTY DRIESELL AWARD, CollegeInsider.com, April 1, 2011.

- ^ Atlantic Sun Recordbook (PDF), Atlantic Sun Conference, p. 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Posnanski, Joe (January 3, 2017). "Will Lefty Driesell ever get in the Hall of Fame?". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ^ Class of 2007 Archived July 14, 2012, at archive.today, The College Basketball Experience at Sprint Center, retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ University of Maryland Athletic Hall of Fame: All-Time Inductees Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, University of Maryland, retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ^ Portsmouth sports legend's loyalty to the city makes him an ace among men Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Virginian-Pilot, August 13, 2008.

- ^ "Lefty returns: Georgia State dedicates court to Driesell". AccessWDUN. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Jarvis Varnado Wins Driesell Award Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, My Fox Memphis, April 2, 2010.

- ^ Markus, Don. "Maryland unveils Lefty Driesell banner in pregame ceremony". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Feinstein, John (March 28, 2018). "Naismith Hall of Fame finally does right by Lefty and votes in Driesell". Washington Post. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Markus, Don (March 31, 2018). "'It means everything': Former Maryland coach Lefty Driesell elected to Naismith Hall of Fame". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "2018 Basketball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony: Live Updates and Highlights". Bleacher Report. September 7, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Feinstein, John (February 24, 2017). "Chuck Driesell, 744 NCAA wins short of his dad, is loving life coaching Maret". Washington Post. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Walton, Carroll Rogers (November 29, 2010). "Lefty Driesell's legacy lives on in daughter Pam, son Chuck". AJC.com. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Driesell's follow-up could be a shot at scouting for Hawks, The Baltimore Sun, January 11, 2003.

- ^ Rosvoglou, Chris (February 17, 2024). "Legendary College Basketball Coach Has Died At 92". The Spun. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1931 births

- 2024 deaths

- American men's basketball players

- American people of German descent

- American Presbyterians

- Basketball coaches from Virginia

- Basketball players from Norfolk, Virginia

- College men's basketball head coaches in the United States

- Davidson Wildcats men's basketball coaches

- Duke Blue Devils men's basketball players

- Georgia State Panthers men's basketball coaches

- High school basketball coaches in the United States

- James Madison Dukes men's basketball coaches

- Maryland Terrapins athletic directors

- Maryland Terrapins men's basketball coaches

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- Sportspeople from Norfolk, Virginia

- Centers (basketball)

- 20th-century American sportsmen