Sotos syndrome

| Sotos syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cerebral gigantism or Sotos-Dodge syndrome |

| |

| Girl displaying characteristic facial features of Sotos syndrome | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Sotos syndrome is a rare genetic disorder characterized by excessive physical growth during the first years of life. Excessive growth often starts in infancy and continues into the early teen years. The disorder may be accompanied by autism,[1] mild intellectual disability, delayed motor, cognitive, and social development, hypotonia (low muscle tone), and speech impairments. Children with Sotos syndrome tend to be large at birth and are often taller, heavier, and have relatively large skulls (macrocephaly) than is normal for their age. Signs of the disorder, which vary among individuals, include a disproportionately large skull with a slightly protrusive forehead, large hands and feet, large mandible, hypertelorism (an abnormally increased distance between the eyes), and downslanting eyes. Clumsiness, an awkward gait, and unusual aggressiveness or irritability may also occur.

Although most cases of Sotos syndrome occur sporadically, familial cases have also been reported. It is similar to Weaver syndrome.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

This syndrome is characterized by overgrowth and advanced bone age. Affected individuals have dysmorphic features, with macrodolichocephaly, downslanting palpebral fissures and a pointed chin. The facial appearance is most notable in early childhood. Affected infants and children tend to grow quickly; they are significantly taller than their siblings and peers, and have an unusually large skull and large head. Adult height is usually in the normal range, although Broc Brown has the condition and was named the world's tallest teenager; as of late 2016, he was 2.34 m (7 ft 8 in) tall and still growing.[2]

Individuals with Sotos syndrome often have intellectual impairment,[3][4] and most also display autistic traits.[5] Frequent behavioral impairments include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), phobias, obsessive compulsive disorder, tantrums, and impulsive behaviors (impulse control disorder). Problems with speech and language are also common.[6] Affected individuals may often have stuttering, difficulty with sound production, or a monotone voice. Additionally, weak muscle tone (hypotonia) may delay other aspects of early development, particularly motor skills such as sitting and crawling.[citation needed]

Other signs include scoliosis, seizures, heart or kidney defects, hearing loss, and problems with vision. Some infants with this disorder experience jaundice and poor feeding. A small number of patients with Sotos syndrome have developed cancer, most often in childhood, but no single form of cancer has been associated with this condition. It remains uncertain whether Sotos syndrome increases the risk of specific types of cancer. If persons with this disorder have any increased cancer risk, their risk is only slightly greater than that of the general population.[7]

Genetics

[edit]

Loss of function mutations in the NSD1 gene lead to the development of Sotos syndrome.[8][9] The NSD1 gene provides instructions for making a protein (histone-lysine N-methyltransferase) that is expressed mainly in the brain, kidney, muscle, spleen, thymus, and lung.[10] In Sotos syndrome, a mutation in the NSD1 gene prevents the production of this protein. The specific function of this protein is not yet known but studies show that it is involved in histone modification, which affects transcription of other genes.[10] It is unclear how a reduced amount of this protein during development leads to learning disabilities, overgrowth, and the other features of Sotos syndrome.[10]

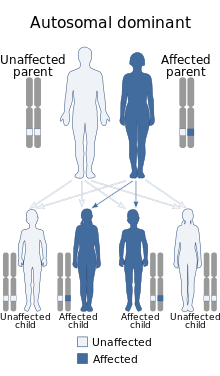

Mutations leading to Sotos syndrome can be sporadic or inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.[10] About 95 percent of Sotos syndrome cases occur by spontaneous mutation involving the NSD1 gene.[10] 5 percent of individuals with Sotos syndrome have one affected parent.[10] In the Japanese population, the most common genetic change leading to Sotos syndrome is a microdeletion in the region of chromosome 5 containing the NSD1 gene (5q35 microdeletion).[11] In Japan, this microdeletion comprises over 50 percent of cases compared to only 10 percent worldwide.[11] In other populations, such as in Europe and the USA, small mutations called intragenic mutations within the NSD1 gene cause a majority of Sotos cases.[11] Individuals with a 5q35 microdeletion in the NSD1 gene have less overgrowth symptoms and more severe learning disability than those with an intragenic mutation.[10] 7 to 35 percent of Sotos patients have no NSD1 anomalies[11].

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of Sotos syndrome is usually made during childhood and is based on clinical examination and bone age.[11] The clinical evaluation begins with a physician conducting a thorough history and physical examination, focusing on signs of excessive growth along with other previously mentioned symptoms. Family history is particularly important to identify any affected family members and provide genetic counseling if necessary.[12] Physicians will also perform an assessment of growth velocity with growth charts and head circumference measurements.[12] Bone age is determined by obtaining an X-ray. Additional diagnostic tests may be performed to rule out other disorders. This includes a complete blood count, karyotype analysis, and measurement of IGF-1, IGFBP-3, free T4, and TSH levels.[12] There are no biochemical markers for Sotos syndrome.[13]The diagnosis is confirmed through genetic testing. Physicians will obtain a blood or saliva sample for genetic testing which looks for a deletion within the NSD1 gene or a heterozygous pathogenic variant of the gene.[10] If there is clinical suspicion of Sotos syndrome in a fetus, physicians may perform genetic testing on the fetus. [14]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment is symptomatic.[13] There is no standard course of treatment for Sotos syndrome.[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]Sotos syndrome is not a life-threatening disorder and patients may have a normal life expectancy. Developmental delays may improve in the school-age years; however, coordination problems may persist into adulthood, along with any learning disabilities and/or other physical or mental issues.[15]

Epidemiology

[edit]Incidence is approximately 1 in 14,000 births.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Exploring Autism". www.exploringautism.org. Archived from the original on 2002-08-11.

- ^ "7-foot-tall Broc Brown: Facts". Morning News USA. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Lane C, Milne E, Freeth M (2016). "Cognition and Behaviour in Sotos Syndrome: A Systematic Review". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0149189. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1149189L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149189. PMC 4752321. PMID 26872390.

- ^ Lane C, Milne E, Freeth M (January 2018). "The cognitive profile of Sotos syndrome" (PDF). J Neuropsychol. 13 (2): 240–252. doi:10.1111/jnp.12146. PMID 29336120.

- ^ Lane C, Milne E, Freeth M (January 2017). "Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Sotos Syndrome". J Autism Dev Disord. 47 (1): 135–143. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-2941-z. PMC 5222916. PMID 27771801.

- ^ a b Lane C, Van Herwegen J, Freeth M (December 2018). "Parent-Reported Communication Abilities of Children with Sotos Syndrome: Evidence from the Children's Communication Checklist-2". J Autism Dev Disord. 49 (4): 1475–1483. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3842-0. PMC 6450847. PMID 30536215.

- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "Sotos syndrome". Genetics Home Reference.

- ^ Kurotaki N, Imaizumi K, Harada N, Masuno M, Kondoh T, Nagai T, et al. (April 2002). "Haploinsufficiency of NSD1 causes Sotos syndrome". Nat. Genet. 30 (4): 365–6. doi:10.1038/ng863. PMID 11896389. S2CID 205357840.

- ^ Melchior L, Schwartz M, Duno M (March 2005). "dHPLC screening of the NSD1 gene identifies nine novel mutations--summary of the first 100 Sotos syndrome mutations". Ann. Hum. Genet. 69 (Pt 2): 222–6. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00150.x (inactive 8 January 2025). PMID 15720303.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2025 (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Tatton-Brown, Katrina; Cole, Trevor RP; Rahman, Nazneen (1993), Adam, Margaret P.; Feldman, Jerry; Mirzaa, Ghayda M.; Pagon, Roberta A. (eds.), "Sotos Syndrome", GeneReviews®, Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, PMID 20301652, retrieved 2025-01-07

- ^ a b c d e Baujat, Geneviève; Cormier-Daire, Valérie (2007-09-07). "Sotos syndrome". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2: 36. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-36. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 2018686. PMID 17825104.

- ^ a b c Manor, Joshua; Lalani, Seema R. (2020). "Overgrowth Syndromes-Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Management". Frontiers in Pediatrics. 8: 574857. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.574857. ISSN 2296-2360. PMC 7661798. PMID 33194904.

- ^ a b "Sotos Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ Chen, Chih-Ping (June 2012). "Prenatal findings and the genetic diagnosis of fetal overgrowth disorders: Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, Sotos syndrome, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome". Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 51 (2): 186–191. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2012.04.004. ISSN 1875-6263. PMID 22795092.

- ^ Foster, Alison; Zachariou, Anna; Loveday, Chey; Ashraf, Tazeen; Blair, Edward; Clayton-Smith, Jill; Dorkins, Huw; Fryer, Alan; Gener, Blanca; Goudie, David; Henderson, Alex (2019). "The phenotype of Sotos syndrome in adulthood: A review of 44 individuals". Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 181 (4): 502–508. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31738. hdl:11343/286377. PMID 31479583. S2CID 201832354.

External links

[edit] Media related to Sotos syndrome at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sotos syndrome at Wikimedia Commons