Central Neo-Aramaic

| Central Neo-Aramaic | |

|---|---|

| Western Neo-Syriac | |

| Geographic distribution | Mardin and Diyarbakır provinces in Turkey, Qamishli and al Hasakah in Syria |

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | turo1240 |

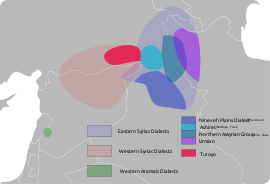

Central Neo-Aramaic, or Northwestern Neo-Aramaic (NWNA), languages represent a specific group of Neo-Aramaic languages, that is designated as Central in reference to its geographical position between Western Neo-Aramaic and other Eastern Aramaic groups. Its linguistic homeland is located in northern parts of the historical region of Syria (modern southeastern Turkey and northeastern Syria). The group includes the Turoyo language as a spoken language of the Tur Abdin region and various groups in diaspora, and Mlahsô language that is recently extinct as a spoken language.[1][2]

Within Aramaic studies, several alternative groupings of Neo-Aramaic languages had been proposed by different researchers, and some of those groupings have used the term Central Neo-Aramaic in a wider meaning, including the widest scope, referring to all Neo-Aramaic languages except for Western Neo-Aramaic and Neo-Mandaic.[3][4]

Definition

[edit]

The narrower definition of the term "Central Neo-Aramaic languages" includes only the Turoyo and Mlahsô languages, while the wider definition also includes the Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA) group. In an attempt to avoid confusion, the narrower group is sometimes referred to as Northwestern Neo-Aramaic, and when combined with NENA it is called Northern Neo-Aramaic.

Both languages that are belonging to this group are termed as Syriac (ܣܘܪܝܝܐ Sūryoyo), and refer to the classical language as either Edessan (ܐܘܪܗܝܐ Ūrhoyo) or Literary (ܟܬܒܢܝܐ Kthobonoyo). The latter name is particularly used for the revived Classical Syriac.

Region

[edit]The smaller Central, or Northwestern, varieties of Neo-Aramaic are spoken by Assyrian Christians traditionally living in the Tur Abdin area of southeastern Turkey and areas around it. Turoyo itself is the closely related group of dialects spoken in Tur Abdin, while Mlahsô is an extinct language once spoken to the north, in Diyarbakır Province.

Other related languages all seem to now be extinct without record. A large number of speakers of these languages have moved to al-Jazira in Syria, particularly the towns of Qamishli and al Hasakah. A number of Turoyo speakers are found in diaspora, with a particularly prominent community in Sweden.

History

[edit]The Central Neo-Aramaic languages have a dual heritage. Most immediately, they have grown out of Eastern Aramaic colloquial varieties that were spoken in the Tur Abdin region and the surrounding plains for a thousand years. However, they have been influenced by Classical Syriac, which itself was the variety of Eastern Aramaic spoken farther west, in the Osroenian city of Edessa. Perhaps the proximity of Central Neo-Aramaic to Edessa, and the closeness of their parent languages, meant that they bear a greater similarity to the classical language than do Northeastern Neo-Aramaic varieties.

However, a clearly separate evolution can be seen in Turoyo and Mlahsô. Mlahsô is grammatically similar to the classical language, and continued to use a similar tense-aspect system to it. However, Mlahsô developed a distinctively clipped phonological palette and systematically turns /θ/→/s/. On the other hand, Turoyo has a quite similar phonology to Classical Syriac, yet it has developed a radically different grammar, sharing similar features with NENA varieties.

First modern studies of Central Neo-Aramaic dialects were initiated during the 19th century,[5] and by the beginning of the 20th century some attempts were made to expand the use of vernacular (Turoyo) into the literary sphere, still dominated by the prolonged use of Classical Syriac among educated adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church. That development was interrupted by the breakout of the First World War (1914–1918) and the atrocities committed during Seyfo (genocide) against various Aramaic-speaking communities, including those in the Tur Abdin region.[6] Displacement of local Christian communities from their native regions created several new groups of Turoyo speakers throughout diaspora. Those events had a long-lasting impact on future development of Turoyo-speaking communities, affecting all spheres of their life, including culture, language and literature.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kim 2008, p. 508.

- ^ Khan 2019b, p. 266.

- ^ Yildiz 2000, p. 23–44.

- ^ Kim 2008, p. 505-531.

- ^ a b Macuch 1990, p. 214.

- ^ Khan 2019b, p. 271.

Sources

[edit]- Bednarowicz, Sebastian (2018). "Neues Alphabet, neue Sprache, neue Kultur: Was kann die Adaptation der lateinischen Schrift für das Turoyo implizieren?". Neue Aramäische Studien: Geschichte und Gegenwart. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 203–214. ISBN 9783631731314.

- Beyer, Klaus (1986). The Aramaic Language: Its Distribution and Subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783525535738.

- Bilgic, Zeki (2018). "Aramäisch des Tur Abdin schreiben und lesen: Überlegungen, warum die Sprechergemeinschaft des Tur Abdin das Neu-Aramäische nicht als Schriftsprache anerkennt". Neue Aramäische Studien: Geschichte und Gegenwart. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 215–250. ISBN 9783631731314.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1989). "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic Literature". ARAM Periodical. 1 (1): 11–23.

- Heinrichs, Wolfhart (1990). "Written Turoyo". Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 181–188. ISBN 9789004369535.

- Ishaq, Yusuf M. (1990). "Turoyo - from Spoken to Written Language". Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 189–199. ISBN 9789004369535.

- Jastrow, Otto (1990). "Personal and Demonstrative Pronouns in Central Neo-Aramaic: A Comparative and Diachronic Discussion Based on Ṭūrōyo and the Eastern Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Hertevin". Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 89–103. ISBN 9789004369535.

- Jastrow, Otto (1993) [1967]. Laut- und Formenlehre des neuaramäischen Dialekts von Mīdin im Ṭūr ʻAbdīn. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447027441.

- Jastrow, Otto (1996). "Passive Formation in Ṭuroyo and Mlaḥsô". Israel Oriental Studies. 16: 49–57. ISBN 9004106464.

- Jastrow, Otto (2011). "Ṭuroyo and Mlaḥsô". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 697–707. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2019). "The Neo-Aramaic Dialects and Their Historical Background". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 266–289. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2019a). "The Neo-Aramaic Dialects of Eastern Anatolia and Northwestern Iran". The Languages and Linguistics of Western Asia: An Areal Perspective. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 190–236. ISBN 9783110421743.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2019b). "The Neo-Aramaic Dialects and Their Historical Background". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 266–289. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Kim, Ronald (2008). "Stammbaum or Continuum? The Subgrouping of Modern Aramaic Dialects Reconsidered". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (3): 505–531.

- Kiraz, George A. (2007). "Kthobonoyo Syriac: Some Observations and Remarks" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 10 (2): 129–142.

- Krotkoff, Georg (1990). "An Annotated Bibliography of Neo-Aramaic". Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 3–26. ISBN 9789004369535.

- Macuch, Rudolf (1990). "Recent Studies in Neo-Aramaic Dialects". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 53 (2): 214–223. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00026045. S2CID 162559782.

- Mengozzi, Alessandro (2011). "Neo-Aramaic Studies: A Survey of Recent Publications". Folia Orientalia. 48: 233–265.

- Owens, Jonathan (2007). "Endangered Languages of the Middle East". Language Diversity Endangered. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 263–277. ISBN 9783110170504.

- Prym, Eugen; Socin, Albert (1881). Der neu-aramaeische Dialekt des Ṭûr 'Abdîn. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht's Verlag.

- Sabar, Yona (2003). "Aramaic, once an International Language, now on the Verge of Expiration: Are the Days of its Last Vestiges Numbered?". When Languages Collide: Perspectives on Language Conflict, Language Competition, and Language Coexistence. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. pp. 222–234. ISBN 9780814209134.

- Sabar, Yona (2009). "Mene Mene, Tekel uPharsin (Daniel 5:25): Are the Days of Jewish and Christian Neo-Aramaic Dialects Numbered?" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 23 (2): 6–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-15.

- Tezel, Aziz (2003). Comparative Etymological Studies in the Western Neo-Syriac (Ṭūrōyo) Lexicon: With Special Reference to Homonyms, Related Words and Borrowings with Cultural Signification. Uppsala: Uppsala University Library. ISBN 9789155455552.

- Tezel, Sina (2015). "Arabic or Ṣūrayt/Ṭūrōyo". Arabic and Semitic Linguistics Contextualized: A Festschrift for Jan Retsö. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 554–568.

- Tezel, Sina (2015). "Neologisms in Ṣūrayt/Ṭūrōyo". Neo-Aramaic in Its Linguistic Context. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 100–109.

- Tomal, Maciej (2015). "Towards a Description of Written Ṣurayt/Ṭuroyo: Some Syntactic Functions of the Particle kal". Neo-Aramaic and its Linguistic Context. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 29–52.

- Weninger, Stefan (2012). "Aramaic-Arabic Language Contact". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 747–755. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Yildiz, Efrem (2000). "The Aramaic Language and its Classification". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 14 (1): 23–44.