Carlos Santana

Carlos Santana | |

|---|---|

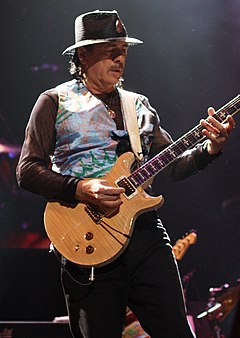

Santana performing in 2011 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Carlos Humberto Santana Barragán[1] |

| Born | July 20, 1947 Autlán de Navarro, Jalisco, Mexico |

| Origin | San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1965–present[update] |

| Labels | |

| Spouses | |

| Website | santana |

Carlos Humberto Santana Barragán[1] (Spanish: [ˈkaɾlos umˈbeɾto sanˈtana βaraˈɣan] ⓘ; born July 20, 1947) is an American guitarist, best known as a founding member of the rock band Santana. Born and raised in Mexico where he developed his musical background, he rose to fame in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States with Santana, which pioneered a fusion of rock and roll and Latin American jazz. Its sound featured his melodic, blues-based lines set against Latin American and African rhythms played on percussion instruments not generally heard in rock, such as timbales and congas. He experienced a resurgence of popularity and critical acclaim in the late 1990s.

In 2015, Rolling Stone magazine listed Santana at No. 20 on their list of the 100 greatest guitarists.[3] In 2023, Rolling Stone named him the 11th greatest guitarist of all time.[4] He has won 10 Grammy Awards and three Latin Grammy Awards,[5] and was inducted along with his namesake band into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998.[6]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Santana was born in Autlán de Navarro in Jalisco, Mexico on July 20, 1947. He learned to play the violin at age five and the guitar at age eight, under the tutelage of his father, who was a mariachi musician.[7] His younger brother, Jorge, also became a professional guitarist.

The family moved from Autlán to Tijuana, on the border with the United States. Carlos' rock and roll career started in the city park: Parque Teniente Guerrero, his mother took him to see the Tj's, the pioneer rock and roll band from the city. TJ (tee jay) is a nickname for Tijuana. They were formed by Javier Bátiz. At the age of 12, Carlos became a roadie and eventually he would join them as a bass player, bass because Bátiz was playing guitar. He later left so he could play guitar in another bar band.[8] The Tj's and Bátiz turned Carlos on to blues music, especially that of T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Howlin' Wolf, and James Brown.

The Santanas then moved to San Francisco, where his father had steady work.[7][9][10][11] In October 1966, Santana started the Santana Blues Band. By 1968, the band had begun to incorporate different types of influences into their electric blues. Santana later said, "If I would go to some cat's room, he'd be listening to Sly [Stone] and Jimi Hendrix; another guy to the Stones and the Beatles. Another guy'd be listening to Tito Puente and Mongo Santamaría. Another guy'd be listening to Miles [Davis] and [John] Coltrane... To me it was like being at a university."[12]

Around the age of eight, Santana fell under the influence of blues performers like B.B. King, Javier Bátiz, Mike Bloomfield, and John Lee Hooker. Gábor Szabó's mid-1960s jazz guitar work also strongly influenced Santana's playing. Indeed, Szabó's composition "Gypsy Queen" was used as the second part of Santana's 1970 treatment of Peter Green's composition "Black Magic Woman", almost down to identical guitar licks. Santana's 2012 instrumental album Shape Shifter includes a song called "Mr. Szabo", played in tribute in the style of Szabó. Santana also credits Hendrix, Bloomfield, Hank Marvin, and Peter Green as important influences; he considered Bloomfield a direct mentor, writing of a key meeting with Bloomfield in San Francisco in the foreword he wrote to a 2000 biography of Bloomfield, Michael Bloomfield: If You Love These Blues – An Oral History.[13] Between the ages of 10 and 12, he was sexually abused by an American man who brought him across the border.[14] Santana lived in the Mission District, graduated from James Lick Middle School, and left Mission High School in 1965. He was accepted at California State University, Northridge and Humboldt State University, but chose not to attend college.[15]

Early career

[edit]"The '60s were a leap in human consciousness. Mahatma Gandhi, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Che Guevara, Mother Teresa, they led a revolution of conscience. The Beatles, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix created revolution and evolution themes. The music was like Dalí, with many colors and revolutionary ways. The youth of today must go there to find themselves."

Santana was influenced by popular artists of the 1950s such as B.B. King, T-Bone Walker, Javier Batiz,[17] and John Lee Hooker.[18] Soon after he began playing guitar, he joined local bands along the "Tijuana Strip", where he was able to begin developing his own sound.[18] He was also introduced to a variety of new musical influences, including jazz and folk music, and witnessed the growing hippie movement centered in San Francisco in the 1960s.[19][20] After several years spent working as a dishwasher at Tic Tock Drive-In No2 and busking to pay for a Gibson SG, replacing a destroyed Gibson Melody Maker,[21] Santana decided to become a full-time musician. In 1966, he was chosen along with other musicians to form an ad hoc band to substitute for that of an intoxicated Paul Butterfield to play a Sunday matinee set at Bill Graham's Fillmore Auditorium. Graham selected the substitutes from musicians he knew primarily through his connections with the Butterfield Blues Band, Grateful Dead, and Jefferson Airplane. Santana's guitar playing caught the attention of both the audience and Graham.[22]

During the same year he and fellow street musicians David Brown (bass guitar), Marcus Malone (percussion) and Gregg Rolie (lead vocals, Hammond Organ B3), formed the Santana Blues Band.[23]

Record deal, Woodstock breakthrough, and height of success: 1969–1972

[edit]

Santana's band was signed by Columbia Records, which shortened its name to simply "Santana".[24] It went into the studio to record its first album in January 1969, finally laying down tracks in May that became its first album. Members were not satisfied with the release, dismissed drummer Bob Livingston, and added Mike Shrieve, who had a strong background in both jazz and rock. Then the band lost percussionist Marcus Malone, who was charged with involuntary manslaughter. Michael Carabello was re-enlisted in his place, bringing with him experienced Nicaraguan percussionist José Chepito Areas.

Major rock music promoter Bill Graham, a Latin music aficionado who had been a fan of Santana from its inception, arranged for the band to appear at the Woodstock Music and Art Festival before its debut album was even released. Its set was one of the surprises of the festival, highlighted by an eleven-minute performance of a throbbing instrumental, "Soul Sacrifice". Its inclusion in the Woodstock film and soundtrack album vastly increased the band's popularity. Graham also suggested Santana record the Willie Bobo song "Evil Ways", as he felt it would get radio airplay. The band's first album, Santana, was released in August 1969 and became a hit, reaching No. 4 on the U.S. Billboard 200.[25]

The band's performance at Woodstock and the follow-up sound track and movie introduced them to an international audience and garnered critical acclaim. The sudden success which followed put pressure on the group, highlighting the different musical directions in which Rolie and Santana were starting to go. Rolie, along with some of the other band members, wanted to emphasize a basic hard rock sound which had been a key component in establishing the band from the start. Santana, however, was increasingly interested in moving beyond his love of blues and rock and wanted more jazzy, ethereal elements in the music. He became fascinated with Gábor Szabó, Miles Davis, Pharoah Sanders, and John Coltrane, as well as developing a growing interest in spirituality. Although Davis and Santana were longtime friends, they only recorded together once, in 1990 for Rustichelli. Santana's band has also included many musicians who also played with Davis.[26] At the same time, Chepito Areas was stricken with a near-fatal brain hemorrhage, and Santana hoped to continue by finding a temporary replacement (first Willie Bobo, then Coke Escovedo), while others in the band, especially Michael Carabello, felt it was wrong to perform publicly without Areas. Cliques formed and the band started to disintegrate.

Consolidating the interest generated by their first album, and their highly acclaimed live performance at the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, the band followed up with their second album, Abraxas, in September 1970. The album's mix of rock, blues, jazz, salsa and other influences was very well received, showing a musical maturation from their first album and refining the band's early sound. Abraxas included two of Santana's most enduring and well-known hits, "Oye Como Va", and "Black Magic Woman/Gypsy Queen". Abraxas spent six weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard chart at the end of 1970.[27] The album remained on the charts for 88 weeks and was certified 4× platinum in 1986.[28] In 2003, the album was ranked number 205 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[29]

Teenage San Francisco Bay Area guitar prodigy Neal Schon joined the Santana band in 1971, in time to complete the third album, Santana III. The band now boasted a powerful dual-lead-guitar act that gave the album a tougher sound. The sound of the band was also helped by the return of a recuperated Chepito Areas and the assistance of Coke Escovedo in the percussion section. Enhancing the band's sound further was the support of popular Bay Area group Tower of Power's horn section, Luis Gasca of Malo, and other session musicians which added to both percussion and vocals, injecting more energy to the proceedings. Santana III was another success, reaching No. 1 on the album charts, selling two million copies, and yielding the hit "No One to Depend On".

Tension between members of the band continued, however. Along with musical differences, drug use became a problem, and Santana was deeply worried that it was affecting the band's performance. Coke Escovedo encouraged Santana to take more control of the band's musical direction, much to the dismay of some of the others who thought that the band and its sound was a collective effort. Also, financial irregularities were exposed while under the management of Stan Marcum, whom Bill Graham criticized as being incompetent. Growing resentments between Santana and Michael Carabello over lifestyle issues resulted in his departure on bad terms. James Mingo Lewis was hired at the last minute as a replacement at a concert in New York City. David Brown later left due to substance abuse problems. A South American tour was cut short in Lima, Peru due to unruly fans and student protests against U.S. governmental policies.

In January 1972, Santana, Schon, Escovedo, and Lewis joined former Band of Gypsys drummer Buddy Miles for a concert at Hawaii's Diamond Head Crater, which was recorded for the album Carlos Santana & Buddy Miles! Live!, which became a gold record.

Caravanserai

[edit]

In early 1972, Santana and the remaining members of the band started working on their fourth album, Caravanserai. During the studio sessions, Santana and Michael Shrieve brought in other musicians: percussionists James Mingo Lewis and Latin-Jazz veteran, Armando Peraza replacing Michael Carabello, and bassists Tom Rutley and Doug Rauch replacing David Brown. Also assisting on keyboards were Wendy Haas and Tom Coster. With the unsettling influx of new players in the studio, Gregg Rolie and Neal Schon decided that it was time to leave after the completion of the album, even though both contributed to the session. Rolie returned home to Seattle; later, he and Schon became founding members of Journey.

When Caravanserai did emerge in 1972, it marked a strong change in musical direction towards jazz fusion. The album received critical praise, but CBS executive Clive Davis warned Santana and the band that it would sabotage the band's position as a "Top 40" act. Nevertheless, over the years, the album achieved platinum status. The difficulties Santana and the band went through during this period were chronicled in Ben Fong-Torres' Rolling Stone 1972 cover story "The Resurrection of Carlos Santana".

Shifting styles and spirituality: 1972–1979

[edit]

In 1972, Santana became interested in the pioneering fusion band the Mahavishnu Orchestra and its guitarist, John McLaughlin. Aware of Santana's interest in meditation, McLaughlin introduced Santana and his wife Deborah to his guru Sri Chinmoy. Chinmoy accepted them as disciples in 1973. Santana was given the name Devadip, meaning "The lamp, light and eye of God". Santana and McLaughlin recorded an album together, Love, Devotion, Surrender (1973) with members of Santana and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, along with percussionist Don Alias and organist Larry Young, both of whom had made appearances, along with McLaughlin, on Miles Davis' classic 1970 album Bitches Brew.

In 1973, Santana, having obtained legal rights to the band's name, Santana, formed a new version of the band with Armando Peraza and Chepito Areas on percussion, Doug Rauch on bass, Michael Shrieve on drums, and Tom Coster and Richard Kermode on keyboards. Santana later was able to recruit jazz vocalist Leon Thomas for the tour supporting Caravanserai in Japan on July 3 and 4, 1973, which was recorded for the 1974 live, sprawling, high-energy triple vinyl LP fusion album Lotus. CBS records would not allow its release unless the material was condensed. Santana did not agree to those terms, and Lotus was available in the U.S. only as an expensive, imported, three-record set. The group later went into the studio and recorded Welcome (1973), which further reflected Santana's interests in jazz fusion and his increasing commitment to the spiritual life of Sri Chinmoy.

A collaboration with John Coltrane's widow, Alice Coltrane, Illuminations (1974), followed. The album delved into avant-garde esoteric free jazz, Eastern Indian and classical influences with other ex-Miles Davis sidemen Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland. Soon after, Santana replaced his band members again. This time Kermode, Thomas and Rauch departed from the group and were replaced by vocalist Leon Patillo (later a successful Contemporary Christian artist) and returning bassist David Brown. He also recruited soprano saxophonist Jules Broussard for the lineup. The band recorded one studio album Borboletta, which was released in 1974. Drummer Leon "Ndugu" Chancler later joined the band as a replacement for Michael Shrieve, who left to pursue a solo career.

By this time Bill Graham's management company had assumed responsibility for the affairs of the group. Graham was critical of Santana's move into jazz and felt he needed to concentrate on getting Santana back into the charts with the edgy, streetwise ethnic sound that had made them famous. Santana himself was seeing that the group's direction was alienating many fans. Although the albums and performances were given good reviews by critics in jazz and jazz fusion circles, sales had plummeted.

Santana, along with Tom Coster, producer David Rubinson, and Chancler, formed yet another version of Santana, adding vocalist Greg Walker. The 1976 album Amigos, which featured the songs "Dance, Sister, Dance" and "Let It Shine", had a strong funk and Latin sound. The album received considerable airplay on FM album-oriented rock stations with the instrumental "Europa (Earth's Cry Heaven's Smile)" and re-introduced Santana to the charts. In 1976, Rolling Stone ran a second cover story on Santana entitled "Santana Comes Home". In February 1976, Santana was presented with fifteen gold discs in Australia, representing sales in excess of 244,000.[30]

The albums conceived through the late 1970s followed the same formula, although with several lineup changes. Among the new personnel who joined was current percussionist Raul Rekow, who joined in early 1977. Most notable of the band's commercial efforts of this era was a version of the 1960s Zombies hit, "She's Not There", on the 1977 double album Moonflower.

Santana recorded two solo projects in this time: Oneness: Silver Dreams – Golden Reality, in 1979 and The Swing of Delight in 1980, which featured Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams.

The pressures and temptations of being a high-profile rock musician and requirements of the spiritual lifestyle which guru Sri Chinmoy and his followers demanded were in conflict, and imposed considerable stress upon Santana's lifestyle and marriage. He was becoming increasingly disillusioned with what he thought were the unreasonable rules that Chinmoy imposed on his life, and in particular with his refusal to allow Santana and Deborah to start a family. He felt too that his fame was being used to increase the guru's visibility. Santana and Deborah eventually ended their relationship with Chinmoy in 1982.

1980s and early 1990s

[edit]

More radio-friendly singles followed from Santana and the band. "Winning" in 1981 (from Zebop!) and "Hold On" (a remake of the Canadian artist Ian Thomas' song) in 1982 both reached the top twenty. After his break with Sri Chinmoy, Santana went into the studio to record another solo album with Keith Olson and legendary R&B producer Jerry Wexler. The 1983 album Havana Moon revisited Santana's early musical experiences in Tijuana with Bo Diddley's "Who Do You Love" and the title cut, Chuck Berry's "Havana Moon". The album's guests included Booker T. Jones, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Willie Nelson, and even Santana's father's mariachi orchestra. Santana again paid tribute to his early rock roots by doing the film score to La Bamba, which was based on the life of rock and roll legend Ritchie Valens and starred Lou Diamond Phillips.

The band Santana returned in 1985 with a new album, Beyond Appearances, and two years later with Freedom. Freedom is the fifteenth studio album by Santana. By this recording, Santana had nine members, some of whom had returned after being with the band in previous versions, including lead singer on the album Buddy Miles. Freedom moved away from the more poppy sound of the previous album Beyond Appearances and back to the band's original Latin rock.

Growing weary of trying to appease record company executives with formulaic hit records, Santana took great pleasure in jamming and making guest appearances with notables such as the jazz fusion group Weather Report, jazz pianist McCoy Tyner, Blues legend John Lee Hooker, Frank Franklin, Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid, and West African singer Salif Keita. He and Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead later recorded and performed with Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji, who conceived one of Santana's famous 1960s drum jams, "Jingo". In 1988, Santana organized a reunion with past members from the Santana band for a series of concert dates. CBS records released a 20-year retrospective of the band's accomplishments with Viva Santana!, a double CD compilation. That same year, Santana formed an all-instrumental group featuring jazz legend Wayne Shorter on tenor and soprano saxophone. The group also included Patrice Rushen on keyboards, Alphonso Johnson on bass, Armando Peraza and Chepito Areas on percussion, and Leon "Ndugu" Chancler on drums. They toured briefly and received much acclaim from the music press, who compared the effort with the era of Caravanserai (1972). Santana released another solo record, Blues for Salvador (1987), which won a Grammy Award for Best Rock Instrumental Performance.

In 1990, Santana left Columbia Records after twenty-two years and signed with Polygram. The following year he made a guest appearance on Ottmar Liebert's album, Solo Para Ti (1991), on the songs "Reaching out 2 U" and on a cover of his own song, "Samba Pa Ti". In 1992, Santana hired the jam band Phish as his opening act.[31] On his 1992 tour, Santana regularly invited some or all of the members of Phish to jam with his band during his headlining performances.[32][33] Phish also toured with Santana in Europe in 1996.[33]

Return to commercial success

[edit]

Santana kicked off the 1990s with a new album Spirits Dancing in the Flesh in 1990. This was followed by Milagro in 1992, a live album Sacred Fire in 1993 and Brothers (a collaboration with his brother Jorge and nephew Carlos Hernandez) in 1994, but sales were relatively poor. Santana toured widely over the next few years but there were no further new album releases, and eventually he was even without a recording contract. However, Arista Records' Clive Davis, who had worked with Santana at Columbia Records, signed him and encouraged him to record a star-studded album with mostly younger artists. The result was 1999's Supernatural, which included collaborations with Everlast, Rob Thomas of Matchbox Twenty, Eric Clapton, Lauryn Hill, Wyclef Jean, CeeLo Green, Maná, Dave Matthews, KC Porter, J. B. Eckl, and others.

However, the lead single was what grabbed the attention of both fans and the music industry. "Smooth", a dynamic cha-cha stop-start number co-written and sung by Rob Thomas of Matchbox Twenty, is laced throughout with Santana's guitar fills and runs. The track's energy was immediately apparent on radio, and it was played on a wide variety of station formats. "Smooth" spent twelve weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming in the process the last No. 1 single of the 1990s. The music video, set on a hot barrio street, was also very popular. Supernatural reached number one on the US album charts and the follow-up single, "Maria Maria", featuring the R&B duo the Product G&B, also hit number one, spending ten weeks there in the spring of 2000. Supernatural eventually shipped over 15 million copies in the United States, and won eight Grammy Awards including Album of the Year, making it Santana's most successful album.

Carlos Santana, alongside the classic Santana lineup of their first two albums, was inducted as an individual into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998. During the ceremony he performed "Black Magic Woman" with the writer of the song, Fleetwood Mac's founder Peter Green. Green was inducted the same night.

In 2000, Supernatural won nine Grammy Awards (eight for Santana personally), including Album of the Year, Record of the Year for "Smooth", and Song of the Year for its writers Thomas and Itaal Shur. Santana's acceptance speeches described his feelings about music's place in one's spiritual existence. Later in the same year at the Latin Grammy Awards, he won three awards including Record of the Year. In 2001, Santana's guitar skills were featured in Michael Jackson's song "Whatever Happens" from the album Invincible.

In 2002, Santana released Shaman, revisiting the Supernatural format of guest artists including Citizen Cope, P.O.D., and Seal. Although the album was not the runaway success its predecessor had been, it produced two radio-friendly hits. "The Game of Love" featuring Michelle Branch rose to number five on the Billboard Hot 100 and spent many weeks at the top of the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart, and "Why Don't You & I", written by and featuring Chad Kroeger from the group Nickelback (the original and a remix with Alex Band from the group the Calling were combined towards chart performance), reached number eight on the Billboard Hot 100. "The Game of Love" went on to win the Grammy Award for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals. In the same year, he was inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame.[34]

In early August 2003, Santana was named fifteenth on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". In 2004, Santana was honored as the Person of the Year by the Latin Recording Academy.[35]

On April 21, 2005, Santana was honored as a BMI Icon at the 12th annual BMI Latin Awards. Santana was the first songwriter designated a BMI Icon at the company's Latin Awards. The honor is given to a creator who has been "a unique and indelible influence on generations of music makers".[36]

In 2005, Herbie Hancock approached Santana to collaborate on an album again using the Supernatural formula. Possibilities was released on August 30, 2005, featuring Carlos Santana and Angélique Kidjo on "Safiatou". Also in 2005, fellow Latin star Shakira invited Santana to play the soft rock guitar ballad "Illegal" on her second English-language studio album Oral Fixation, Vol. 2.

Santana's 2005 album All That I Am consists primarily of collaborations with other artists. The first single, the peppy "I'm Feeling You", again featured Michelle Branch and the Wreckers. Other musicians joining this time included Steven Tyler of Aerosmith, Kirk Hammett from Metallica, hip-hop artist/songwriter/producer will.i.am, guitarist/songwriter/producer George Pajon, hip-hop/reggae star Sean Paul, and R&B singer Joss Stone. In April and May 2006, Santana toured Europe, where he promoted his son Salvador Santana's band as his opening act.

In 2007, Santana appeared, along with Sheila E. and José Feliciano, on Gloria Estefan's album 90 Millas, on the single "No Llores". He also teamed again with Chad Kroeger for the hit single "Into the Night". He also played guitar in Eros Ramazzotti's hit "Fuoco nel fuoco" from the album e².

In 2008, Santana was reported to be working with his longtime friend, Marcelo Vieira, on his solo album Acoustic Demos, which was released at the end of the year. It features tracks such as "For Flavia" and "Across the Grave", the latter said to feature heavy melodic riffs by Santana.

Santana performed at the 2009 American Idol Finale with the top 13 finalists, which starred many acts such as KISS, Queen and Rod Stewart. On July 8, 2009, Santana appeared at the Athens Olympic Stadium in Athens with his 10-member all-star band as part of his "Supernatural Santana – A Trip through the Hits" European tour. On July 10, 2009, he also appeared at Philip II Stadium in Skopje. With a 2.5-hour long concert and 20,000 people, Santana appeared for the first time in that region. "Supernatural Santana – A Trip through the Hits" was played through 2011 at the Hard Rock Hotel in Las Vegas.

Santana is featured as a playable character in the music video game Guitar Hero 5. A live recording of his song "No One to Depend On" is included in the game, which was released on September 1, 2009.[37] More recently in 2011, three Santana songs were offered as downloadable content (DLC) for guitar learning software Rocksmith: "Oye Como Va", "Smooth", and "Black Magic Woman/Gypsy Queen". In the same year, Santana received the Billboard Latin Music Lifetime Achievement Award.[38]

In 2007 Santana along with chef Roberto Santibañez.opened a chain of upscale Mexican restaurants called "Maria Maria". The restaurants were located in Tempe, Arizona, Mill Valley, Walnut Creek, Danville, San Diego, Austin, Texas, and Boca Raton, Florida.[39] As of 2021, the only open location is in Walnut Creek.[40]

In 2012, Santana released an album Shape Shifter consisting of mostly instrumental tracks. On February 23, 2013, there was a public announcement on ultimateclassicrock.com about a reunion of the surviving members (minus Jose "Chepito" Areas) of the Santana band that recorded Santana III in 1971. The next album was titled Santana IV. On May 6, 2014, his first-ever Spanish-language album[41] Corazón was released.

On September 12, 2015, Santana appeared as a member of Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh's band Phil Lesh and Friends at the third annual Lockn' Festival. He has continued to act as a mentor to a younger generation of jam acts, like Derek Trucks and Robert Randolph.[42]

In 2016, Carlos Santana reunited with past Santana band members Gregg Rolie, Michael Carabello, Michael Shrieve, and Neil Schon, releasing the album Santana IV and embarking with the band on a brief tour. A full set from this lineup was filmed at the House of Blues in Las Vegas and released as a live album and DVD titled Live at the House of Blues Las Vegas.

In 2017, Santana collaborated with the Isley Brothers to release the album The Power of Peace on July 28, 2017.

In December 2018, Santana published a guitar lesson on YouTube as part of the online education series MasterClass.[43]

In October 2019, Santana was featured on the American rapper Tyga's song "Mamacita" alongside American rapper YG. The song's music video premiered on YouTube on 25 October.

In March 2020, Santana's "Miraculous World Tour" was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[44]

In August 2021, Santana signed a new global record deal with BMG to release his new full-length studio album Blessings and Miracles.[45] In the same month, he performed in New York's Central Park along with Rob Thomas and Wyclef Jean.[46]

In August 2023, Santana received some controversy regarding statements he made about trans people, stating "...a woman is a woman and a man is a man".[47] He would apologize a day later for his remarks.[48]

Equipment

[edit]Guitars and effects

[edit]

Santana played a red Gibson SG Special with P-90 pickups at the Woodstock festival (1969). During 1970–1972, between the release of Abraxas (1970) and Santana III 1971, he used different Gibson Les Pauls and a black Gibson SG Special. In 1974, he played and endorsed the Gibson L6-S Custom. This can be heard on the album Borboletta (1974). From 1976 until 1982, his main guitar was a Yamaha SG 175B, and sometimes a white Gibson SG Custom with three open-coil pick-ups. In 1982, he started to use a custom-made PRS Custom 24 guitar. In 1988, PRS Guitars began making Santana signature model guitars, which Santana has played through their various iterations ever since (see below).

Santana currently uses a Santana II model guitar fitted with PRS Santana III nickel-covered pickups, a tremolo bar, and .009–.042 gauge D'Addario strings. He also plays a PRS Santana MD "The Multidimensional" guitar.[49] The Santana guitars feature necks made of a single piece of mahogany topped with rosewood fretboard; some feature highly sought-after Brazilian rosewood.[50]

Santana Signature models:

- PRS Santana I "The Yellow" guitar (1988)

- PRS Santana II "Supernatural" guitar (1999)

- PRS Santana III guitar (2001)

- PRS Santana SE guitar (2001)

- PRS Santana SE II guitar (2003)

- PRS Santana Shaman SE-Limited Edition guitar (2003)

- PRS Santana MD "The Multidimensional" guitar (2008)

- PRS Santana 25th Anniversary guitar (2009)

- PRS Santana Abraxas SE-Limited Edition guitar (2009)

- PRS Santana SE "The Multidimensional" guitar (2011)

- PRS Santana Retro guitar (2017)

- PRS Santana Yellow SE guitar (2017)

Santana also uses a classical guitar, the Alvarez Yairi CY127CE with Alvarez tension nylon strings,[51] and in recent years (from 2009) he uses custom-made, semi-hollow Toru Nittono's "Model-T" Jazz Electric Nylon.[52]

Santana does not use many effects pedals. His PRS guitar is connected to a Mu-Tron Wah-wah pedal (or, more recently, a Dunlop 535Q wah[53] and a T-Rex Replica delay pedal,[53][54] then through a customized Jim Dunlop amp switcher which in turn is connected to the different amps or cabinets.

Previous setups include an Ibanez Tube Screamer[55] right after the guitar. He is also known to have used an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff distortion for his famous sustain. In the song "Stand Up" from the album Marathon (1979), Santana uses a Heil talk box in the guitar solo. He has also used the Audiotech Guitar Products 1x6 Rack Mount Audio Switcher in rehearsals for the 2008 "Live Your Light" tour.

Santana uses two different guitar picks: the large triangular Dunlop he has used for many years, and the V-Pick Freakishly Large Round.

Amplifiers

[edit]Santana's distinctive guitar tone is produced by PRS Santana signature guitars plugged into multiple amplifiers. The amps consist of a Mesa Boogie Mark I, Dumble Overdrive Reverb and more recently a Bludotone amplifier. Santana compares the tonal qualities of each amplifier to that of a singer producing head/nasal tones, chest tones, and belly tones. A three-way amp switcher is employed on Carlos's pedal board to enable him to switch between amps. Often the unique tones of each amplifier are blended together, complementing each other producing a richer tone.

He also put the "Boogie" in Mesa Boogie. Santana is credited with coining the popular Mesa amplifier name when he tried one and exclaimed, "That little thing really Boogies!"[56]

Specifically, Santana combines a Mesa/Boogie Mark I head running through a Boogie cabinet with Altec 417-8H (or recently JBL E120s) speakers, and a Dumble Overdrive Reverb and/or a Dumble Overdrive Special running through a Brown or Marshall 4x12 cabinet with Celestion G12M "Greenback" speakers, depending on the desired sound. Shure KSM-32 microphones are used to pick up the sound, going to the PA. Additionally, a Fender Cyber-Twin Amp is mostly used at home.

During his early career, Santana used a GMT transistor amplifier stack and a silverface Fender Twin. The GMT 226A rig was used at the Woodstock concert as well as during recording Santana's debut album. During this era, Santana also began to use the Fender Twin, which was also used on the debut and later at the recording sessions of Abraxas.

Personal life

[edit]In 1965, Santana became a naturalized U.S. citizen.[57]

After discovering Chinmoy and Yogananda in 1972, Santana quit marijuana until 1981.[58] In 2020, Santana launched his own brand of cannabis named Mirayo that honours "the spiritual and ancient Latin heritage of the plant."[59]

From 1973 to 2007, he was married to Deborah King, daughter of blues musician Saunders King. They have three children, Salvador, Stella, and Angelica,[60] and co-founded the Milagro (Miracle) Foundation, a non-profit organization which provides financial aid for educational, medical, and other needs.[61][62] He stated in 2000 that he communicates with the angel Metatron.[63] In 2007, King filed for divorce after 34 years of marriage, citing irreconcilable differences.[64] On July 9, 2010, Santana proposed to his touring drummer Cindy Blackman on stage during a concert at Tinley Park, Illinois. The two were married in December 2010[65][66] and currently live in Las Vegas.[67]

Santana underwent heart surgery in December 2021. He suffered an undisclosed medical emergency on stage at a concert at Pine Knob Music Theatre in Michigan on July 5, 2022, but was able to gain consciousness while being helped off the stage.[68] A statement from his publicist later announced that he had collapsed from heat and dehydration, but was being observed at the local hospital and would recover soon. His show scheduled for the day after was postponed.[69] On July 8, 2022, Santana's management company said that he would postpone his next six concerts out of an "abundance of caution for the artist's health".[70]

In an interview with Rolling Stone in 2000, Santana spoke of his Christian faith and how it helped to guide him through some of the most troubling times in his life[71]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Love Devotion Surrender (1973)

- Illuminations (1974)

- Oneness – Silver Dreams Golden Reality (1979)

- The Swing of Delight (1980)

- Havana Moon (1983)

- Blues for Salvador (1987)

- Santana Brothers (1993)

Memoir

[edit]On November 4, 2014, his memoir The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light was published.[41][72] ISBN 978-0-31624-492-3

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Year[a] | Category | Recipients | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billboard | 1995 | Billboard Century Award | Carlos Santana | Won | [73] |

| 2009 | Lifetime Achievement Award | Won | [74] | ||

| 2015 | Spirit of Hope | Won | [75] | ||

| CHCI Medallions of Excellence | 1999 | Medallion of Excellence for Community Service | Won | [76] | |

| Chicano Music Awards | 1997 | Latino Music Legend of the Year | Won | [77] | |

| Echo Music Prize | 2001 | Best International Rock/Pop Male Artist | Won | [78] | |

| Grammy Awards | 1988 | Best Rock Instrumental Performance (Orchestra, Group Or Soloist) | Blues for Salvador | Won | [79] |

| 2003 | Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals | "The Game of Love" (with Michelle Branch) | Won | [80] | |

| Hollywood Walk of Fame | 1997 | A star located at 7080 Hollywood Blvd | Carlos Santana | Inducted | [81] |

| International Latin Music Hall of Fame | 2002 | International Latin Music Hall of Fame | Inducted | [82] | |

| Kennedy Center Honors | 2013 | Kennedy Center Honoree | Inducted | [83] | |

| Latin Grammy Awards | 2004 | Person of the Year | Won | [84] | |

| NAACP Image Award | 2006 | NAACP Image Award – Hall of Fame Award | Inducted | [85] | |

| Patrick Lippert Award | 2001 | Patrick Lippert Award | Won | [86] | |

| UCLA Cesar E. Chavez Spirit Award | 2001 | Award for social engagement | Carlos Santana and Deborah Santana | Won | [87] |

| VH1 awards | 2000 | Man of the Year | Carlos Santana | Won | [88] |

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Indicates the year of ceremony. Each year is linked to the article about the awards held that year, wherever possible.

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Ovalle, Juan Martín (March 29, 2019). "Un verano con el legendario Carlos Santana". Fort Worth Star-Telegram (in Spanish).

- ^ "RCA's Peter Edge, Tom Corson on the Shuttering of Jive, J and Arista". Billboard. October 7, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ "100 Greatest Guitarists". Rolling Stone. December 18, 2015. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ "The 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "Santana received 10 Grammy Awards and 3 Latin Grammy Awards". AllMusic. 1999. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ "Santana". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Brichi, Karim. "1947-1966". Santanamigos. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Santana, Carlos (November 4, 2014). The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-24491-6.

- ^ "The Latin American Club". PUNCH. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Third Eye Blind's Stephan Jenkins Walks Us Down Valencia Street in San Francisco's Mission". vice.com. April 13, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Bay Area". engineering.osu.edu. April 29, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Szatmary, David P. (2014). Rockin' in Time. United States: Pearson. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-205-93624-3.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Influences". Dougpayne.com. April 23, 1977. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Santana Says He Was Molested As A Child". MTV News. MTV. March 2, 2000. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ "50 facts from life of Carlos Santana". BOOMSbeat. December 29, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ Carlos Santana: I’m Immortal interview by Punto Digital, October 13, 2010.

- ^ "Javier Bátiz, Santana – I love you much too much (en directo)". June 2, 2015. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "Carlos Santana – the king of World Music". La Voz. 24 (34). Denver: La Voz Publishing Company: 11. August 26, 1998. ISSN 0746-0988. OCLC 9747738.

When the family moved to the boom town of Tijuana in 1955, 8-year-old Carlos picked up the guitar, studying and emulating the sounds of B.B. King, T-Bone Walker, and John Lee Hooker. Soon he was playing with local bands like "T.J.'s," where he added his own unique touch and feel to the popular songs of '50s rock 'n' roll. As he continued to play with different bands along the busy "Tijuana Strip," he started to perfect his style and sound.

- ^ Kopp, Bill (June 11, 2019). "Why Carlos Santana Calls Himself a 'Real Hippie'". Good Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "Return of the hippie". The Guardian. February 10, 2000. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Santana, Carlos (November 4, 2014). The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-24491-6.

That's how I began my career as a dishwasher at the Tic Tock Drive In. I worked at the one at 3rd and King

- ^ Shapiro, Marc, "Carlos Santana: Back on Top”, pages 57–58, St. Martin’s Press, ISBN 0-312-26904-8, 2000.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William (2003). "Carlos Santana > Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ Santana. Sony. 1998. 489542-2.

- ^ "The Day Santana Met Miles Davis". The Daily Beast. January 25, 2015.

- ^ "Chart Beat Bonus". Billboard. November 1, 2002. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Santana – Abraxas". Superseventies.com. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ Levy, Joe; Steven Van Zandt (2006) [2005]. "205 | Abraxas – Santana". Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (3rd ed.). London: Turnaround. ISBN 1-932958-61-4. OCLC 70672814. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- ^ "Material Returns" (PDF). Cash Box. February 21, 1976. p. 48. Retrieved November 21, 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Two sets of Phish opening for Santana, summers '92 and '96". KDRT 95.7FM Davis. June 3, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ Puterbaugh, Parke (2009). Phish: The Biography. Hachette Books. p. 107. ISBN 9780306819476.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Scott. "Watch Phish Guest With Santana At Blossom In 1992: Video". JamBase. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "International Latin Music Hall of Fame Announces Inductees for 2002". April 5, 2002. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "Latin honours for Carlos Santana". BBC News. May 25, 2004. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ "Artists Announced for Tribute to Carlos Santana at BMI Latin Awards in Las Vegas". bmi.com. March 22, 2005. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Grooves in Guitar Hero 5, which included the song black magic woman". idiomag. July 21, 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ^ "Carlos Santana set for lifetime award". The Hollywood Reporter. April 23, 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Ella Lawrence (January 28, 2010). "Carlos Santana opens Maria Maria in Danville". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Maria Maria Restaurants". Maria Maria Restaurants. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "In Music, Carlos Santana Seeks The Divine". NPR. November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Interview: Carlos Santana Discusses His MasterClass on "The Art and Soul of Guitar"". Relix.com. March 6, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Joins Online MasterClass Teaching Staff". L4LM. December 13, 2018.

- ^ "Santana Cancel European Tour Due To Coronavirus". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Grammy award-winning artist and guitarist Carlos Cantana signs with BMG". Music Business Worldwide. August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ "NYC Central Park Homecoming Concert". CNN. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (August 24, 2023). "Carlos Santana Shared His Thoughts on Trans People, for Some Reason". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Daw, Stephen (August 25, 2023). "Carlos Santana Apologizes for 'Insensitive Comments' About Transgender Community". Billboard. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Santana – Musician's Corner – Blue Guitar". Santana.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Santana – Musician's Corner – Red Guitar". Santana.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Santana – Musician's Corner – Acoustic Guitar". Santana.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Toru Nittono Guitars". Nittonoguitars.com. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ a b [2] Archived March 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [3] Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [4] Archived May 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Mesa Boogie Story – a history". Mesaboogie.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to the Pacific Coast Immigration Museum". learn.pacificcoastimmigration.org. Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff (March 24, 2018). "Carlos Santana Interview: 'Music is a Beam of Light'". Best Classic Bands. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Trakin, Roy (October 7, 2020). "Carlos Santana Launches Cannabis Brand Honoring Plant's 'Latin Heritage'". Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Carlos Santana". Biography.com. May 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Milagro Foundation". Carlosshoesformen.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "The Milagro Foundation: Making a difference in the lives of children through health, education, and the arts". Milagrofoundation.org. Archived from the original on November 10, 2000. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Heath, Chris (March 16, 2000). "The Epic Life of Carlos Santana". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Dean Goodman (July 12, 2010). "Carlos Santana proposes onstage to girlfriend". Reuters. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Is Engaged!". Us Weekly. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Proposes to Drummer Girlfriend Onstage". Billboard. July 12, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Realtor – Real Estate News and Advice Community". Realtor.com. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ Lincoln, Ross A. (July 5, 2022). "Carlos Santana Passes Out During Michigan Concert". Yahoo.com. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "NEW: Statement from Carlos Santana's PR. Santana was overcome with heat exhaustion and dehydration. He is now doing well according to his rep". Twitter.com. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Atkinson, Katie (July 8, 2022). "Carlos Santana Postpones 6 Concerts After Collapsing Onstage". Billboard. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Talks about How Christian Faith Saved Him After Seven Suicide Attempts". www.hallels.com. October 2, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Carlos Santana: 'I Am A Reflection Of Your Light'". NPR. November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Tony Bennett To Receive Billboard's Century Award". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media. August 4, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ "Carlos Santana set for lifetime award". The Hollywood Reporter. April 23, 2009. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "Roberto Carlos and Carlos Santana to Be Honored at Billboard Latin Music Awards". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. April 3, 2015. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "CHCI Medallion of Excellence Awardees". Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ Europa Publications (2003). Sleeman, Elizabeth (ed.). The International Who's Who 2004. Psychology Press. p. 1478. ISBN 978-1-85743-217-6.

- ^ "Echoes Debut in Berlin". Billboard. Vol. 113, no. 13. Nielsen Business Media. March 31, 2001. p. 82. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ "Carlos Santana | Artist". The Recording Academy. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ "Carlos Santana". GRAMMY.com. November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame Carlos Santana". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ "International Latin Music Hall of Fame Announces Inductees for 2002". April 5, 2002. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "List of Kennedy Center Honorees". Kennedy-center.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Latin honours for Carlos Santana". BBC News. May 25, 2004. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ "Carlos Santana To Be Inducted Into NAACP Image Awards Hall Of Fame". Ultimate Guitar. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ ""Rock the Vote": How a Battle Against Rock Censorship Became a Transformation of Voting Among American Youth". Rock & Roll Library. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "Director's contribution to Chicano movement honored". Daily Bruin. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ "The Eye". Billboard. Vol. 112, no. 51. Nielsen Business Media. December 16, 2000. p. 84. ISSN 0006-2510.

General sources

[edit]- Soul Sacrifice: The Carlos Santana Story, Simon Leng, 2000

- Space Between the Stars, Deborah Santana, 2004

- Rolling Stone, "The Resurrection of Carlos Santana", Ben Fong Torres, 1972

- New Musical Express, "Spirit of Santana". Chris Charlesworth, November 1973

- Guitar Player Magazine, 1978

- Rolling Stone, "The Epic Life of Carlos Santana", 2000

- Santana I – Sony Legacy Edition: liner notes

- Abraxas – Sony Legacy Edition: liner notes

- Santana III – Sony Legacy edition: liner notes

- Viva Santana – CBS CD release 1988; liner notes

- Power, Passion and Beauty – The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra Walter Kolosky 2006

- Best of Carlos Santana – Wolf Marshall 1996; introduction and interview

Further reading

[edit]- Leng, Simon (2000). Soul Sacrifice: The Santana Story. London: Firefly Pub. ISBN 0-946719-29-2.

- McCarthy, Jim (2004). Voices of Latin Rock: The People and Events That Created This Sound (1st ed.). Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corp. ISBN 0-634-08061-X.

Sansoe, Ron, foreword by Carlos Santana

- Molenda, Michael (ed.). Guitar Player Presents Carlos Santana, Backbeat Books, 2010, 124 pp., ISBN 978-0-87930-976-3

- Remstein, Henna. Carlos Santana (Latinos in the Limelight), Chelsea House Publications, 2001, 64 pp., ISBN 0-7910-6473-5

- Santana, Deborah (King); Miller, Hal; Faulkner, John (ed.), with a foreword by Bill Graham. Santana: A Retrospective of the Santana Band's Twenty Years in Music, San Francisco Mission Cultural Center, 1987, 50 pp., no ISBN. OCLC 77798816 Includes a 4-p genealogical tree w/the member's name for every Santana band from 1966. Copy at SFPL

- Santana, Deborah (King) (March 1, 2005). Space Between the Stars: My Journey to an Open Heart (1st ed.). New York: One World/Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0345471253.

- Shapiro, Marc (2000). Carlos Santana: Back on Top. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-28852-2.

- Slavicek, Louise Chipley (2006). Carlos Santana. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-8844-8.

Juvenile literature

- Sumsion, Michael. Maximum Santana: The Unauthorized Biography of Santana, Chrome Dreams, 2003, ISBN 1-84240-107-6. A CD-audio biog

- Weinstein, Norman (2009). Carlos Santana: A Biography. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-35420-5.

- Woog, Adam (2007). Carlos Santana: Legendary Guitarist. Detroit: Lucent Books. ISBN 978-1-59018-972-6.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Milagro Foundation

- Music Carlos Santana Archived August 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Carlos Santana at IMDb

- Carlos Santana

- 1947 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 21st-century American male musicians

- American Book Award winners

- American male guitarists

- American male songwriters

- American musicians of Mexican descent

- American philanthropists

- American rock guitarists

- American rock songwriters

- American world music musicians

- Arista Records artists

- American blues rock musicians

- Chicano rock musicians

- Columbia Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- Guitarists from San Francisco

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Latin Grammy Award winners

- Latin music songwriters

- Latin Recording Academy Person of the Year honorees

- American lead guitarists

- Mexican emigrants to the United States

- Mexican expatriates in the United States

- Musicians from Jalisco

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- People from Autlán, Jalisco

- People from Tijuana

- Polydor Records artists

- RCA Records artists

- Santana (band) members

- Songwriters from California

- Jazz fusion guitarists

- Fania All-Stars members