Caral–Supe civilization

Map of Caral–Supe sites showing their locations in Peru | |

| Alternative names | Caral, Norte Chico |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Lima, Peru |

| Period | Cotton pre-ceramic |

| Dates | c. 3,500 BCE – c. 1,800 BCE |

| Type site | Aspero |

| Preceded by | Lauricocha |

| Followed by | Kotosh |

| History of Peru |

|---|

|

|

|

Caral–Supe (also known as Caral and Norte Chico) was a complex Pre-Columbian era society that included as many as thirty major population centers in what is now the Caral region of north-central coastal Peru. The civilization flourished between the fourth and second millennia BC, with the formation of the first city generally dated to around 3500 BC, at Huaricanga, in the Fortaleza area.[1] From 3100 BC onward, large-scale human settlement and communal construction become clearly apparent.[2] This lasted until a period of decline around 1800 BC.[3] Since the early 21st century, it has been recognized as the oldest-known civilization in the Americas, and as one of the six sites where civilization separately originated in the ancient world.[4]

This civilization flourished along three rivers, the Fortaleza, the Pativilca, and the Supe. These river valleys each have large clusters of sites. Farther south, there are several associated sites along the Huaura River.[5] The name Caral–Supe is derived from the city of Caral[6] in the Supe Valley, a large and well-studied Caral–Supe site.

Complex society in the Caral–Supe arose a millennium after Sumer in Mesopotamia, was contemporaneous with the Egyptian pyramids, and predated the Mesoamerican Olmecs by nearly two millennia.

In archaeological nomenclature, Caral–Supe is a pre-ceramic culture of the pre-Columbian Late Archaic; it completely lacked ceramics and no evidence of visual art has survived. The most impressive achievement of the civilization was its monumental architecture, including large earthwork platform mounds and sunken circular plazas. Archaeological evidence suggests use of textile technology and, possibly, the worship of common deity symbols, both of which recur in pre-Columbian Andean civilizations. Sophisticated government is presumed to have been required to manage the ancient Caral. Questions remain over its organization, particularly the influence of food resources on politics.

Archaeologists have been aware of ancient sites in the area since at least the 1940s; early work occurred at Aspero on the coast, a site identified as early as 1905,[7] and later at Caral, farther inland. In the late 1990s, Peruvian archaeologists, led by Ruth Shady, provided the first extensive documentation of the civilization with work at Caral.[8] A 2001 paper in Science, providing a survey of the Caral research,[9] and a 2004 article in Nature, describing fieldwork and radiocarbon dating across a wider area,[2] revealed Caral–Supe's full significance and led to widespread interest.[10]

History and geography

[edit]

The dating of the Caral–Supe sites has pushed back the estimated beginning date of complex societies in the Peruvian region by more than one thousand years. The Chavín culture, c. 900 BC, had previously been considered the first civilization of the area. Regularly, it still is cited incorrectly as such in general works.[11][12]

The discovery of Caral–Supe has also shifted the focus of research away from the highland areas of the Andes and lowlands adjacent to the mountains (where the Chavín, and later Inca, had their major centers) to the Peruvian littoral, or coastal regions. Caral is located in a north-central area of the coast, approximately 150 to 200 km north of Lima, roughly bounded by the Lurín Valley on the south and the Casma Valley on the north. It comprises four coastal valleys: the Huaura, Supe, Pativilca, and Fortaleza. Known sites are concentrated in the latter three, which share a common coastal plain. The three principal valleys cover only 1,800 km², and research has emphasized the density of the population centers.[13]

The Peruvian littoral appears an "improbable, even aberrant" candidate for the "pristine" development of civilization, compared to other world centers.[1] It is extremely arid, bounded by two rain shadows (caused by the Andes to the east, and the Pacific trade winds to the west). The region is punctuated by more than 50 rivers that carry Andean snowmelt. The development of widespread irrigation from these water sources is seen as decisive in the emergence of Caral–Supe;[3][14] since all of the monumental architecture at various sites has been found close to irrigation channels.[citation needed]

The radiocarbon work of Jonathan Haas et al., found that 10 of 95 samples taken in the Pativilca and Fortaleza areas dated from before 3500 BC. The oldest, dating from 9210 BC, provides "limited indication" of human settlement during the Pre-Columbian Early Archaic era. Two dates of 3700 BC are associated with communal architecture, but are likely to be anomalous. It is from 3200 BC onward that large-scale human settlement and communal construction are clearly apparent.[2] Mann, in a survey of the literature in 2005, suggests "sometime before 3200 BC, and possibly before 3500 BC" as the beginning date of the Caral–Supe formative period. He notes that the earliest date securely associated with a city is 3500 BC, at Huaricanga, in the Fortaleza area of the north, based on Haas's dates.[1]

Haas's early third millennium dates suggest that the development of coastal and inland sites occurred in parallel. But, from 2500 to 2000 BC, during the period of greatest expansion, the population and development decisively shifted toward the inland sites. All development apparently occurred at large interior sites such as Caral, although they remained dependent on fish and shellfish from the coast.[2] The peak in dates is in keeping with Shady's dates at Caral, which show habitation from 2627 BC to 2020 BC.[9] That coastal and inland sites developed in tandem remains disputed, however (see next section).[citation needed]

Influence

[edit]By around 2200 BC, the influence of Norte Chico civilization spread far along the coast. To the south, it went as far as the Chillon valley, and the site of El Paraiso. To the north, it spread as far as the Santa River valley.[15]

The Caral–Supe civilization began to decline c. 1800 BC, with more powerful centers appearing to the south and north along the coast, and to the east inside the belt of the Andes. The success of irrigation-based agriculture at Caral–Supe may have contributed to its being eclipsed. Anthropologist Professor Winifred Creamer of Northern Illinois University notes that "when this civilization is in decline, we begin to find extensive canals farther north. People were moving to more fertile ground and taking their knowledge of irrigation with them".[3] It would be 1,000 years before the rise of the next great Peruvian culture, the Chavín.[citation needed]

Geographical links

[edit]Cultural links with the highland areas have been noted by archaeologists. Ruth Shady highlights the links with the Kotosh Religious Tradition:[16]

Numerous architectural features found among the settlements of Supe, including subterranean circular courts, stepped pyramids and sequential platforms, as well as material remains and their cultural implications, excavated at Aspero and the valley sites we are digging (Caral, Chupacigarro, Lurihuasi, Miraya), are shared with other settlements of the area that participated in what is known as the Kotosh Religious Tradition. Most specific among these features include rooms with benches and hearths with subterranean ventilation ducts, wall niches, biconvex beads, and musical flutes.[17][excessive quote]

Maritime coast and agricultural interior

[edit]Research into Caral–Supe continues, with many unsettled questions. Debate is ongoing regarding two related questions: the degree to which the flourishing of the Caral–Supe was based on maritime food resources, and the exact relationship this implies between the coastal and inland sites.[NB 1]

Confirmed diet

[edit]A broad outline of the Caral–Supe diet has been suggested. At Caral, the edible domesticated plants noted by Shady are squash, beans, lúcuma, guava, pacay (Inga feuilleei), and sweet potato.[9] Haas et al. noted the same foods in their survey farther north, while adding avocado and achira. In 2013, evidence for maize also was documented by Haas et al. (see below).[18]

There was also a significant seafood component at both coastal and inland sites. Shady notes that "animal remains are almost exclusively marine" at Caral, including clams and mussels, and large amounts of anchovies and sardines.[9] That the anchovy fish reached inland is clear,[1] although Haas suggests that "shellfish [which would include clams and mussels], sea mammals, and seaweed do not appear to have been significant portions of the diet in the inland, non-maritime sites".[13]

Theory of a maritime foundation for Andean civilization

[edit]

The role of seafood in the Caral–Supe diet has aroused debate. Much early fieldwork was conducted in the region of Aspero on the coast, before the full scope and inter-connectedness of the several sites of the civilization were realized. In a 1973 paper, Michael E. Moseley contended that a maritime subsistence (seafood) economy had been the basis of the society and its remarkably early flourishing,[7] a theory later elaborated as a "maritime foundation of Andean civilization" (MFAC).[19][20] He confirmed a previously observed lack of ceramics at Aspero, and he deduced that "hummocks" on the site constituted the remains of artificial platform mounds.[citation needed]

This thesis of a maritime foundation was contrary to the general scholarly consensus that the rise of civilization was based on intensive agriculture, particularly of at least one cereal. The production of agricultural surpluses had long been seen as essential in promoting population density and the emergence of complex society. Moseley's ideas would be debated and challenged (that maritime remains and their caloric contribution were overestimated, for example),[21] but have been treated as plausible as late as 2005, when Mann conducted a summary of the literature.[1]

Concomitant to the maritime subsistence hypothesis was an implied dominance of sites immediately adjacent to the coast over other centers. This idea was shaken by the realization of the magnitude of Caral, an inland site. Supplemental to a 1997 article by Shady dating Caral, a 2001 Science news article emphasized the dominance of agriculture and also suggested that Caral was the oldest urban center in Peru (and the entire Americas). It rejected the idea that civilization might have begun adjacent to the coast and then moved inland. One archaeologist was quoted as suggesting that "rather than coastal antecedents to monumental inland sites, what we have now are coastal satellite villages to monumental inland sites".[14]

These assertions were quickly challenged by Sandweiss and Moseley, who observed that Caral, although being the largest and most complex preceramic site, it is not the oldest. They admitted the importance of agriculture to industry and to augment diet, while broadly affirming "the formative role of marine resources in early Andean civilization".[22] Scholars now agree that the inland sites did have significantly greater populations, and that there were "so many more people along the four rivers than on the shore that they had to have been dominant".[1]

The remaining question is which of the areas developed first and created a template for subsequent development.[23] Haas rejects suggestions that maritime development at sites immediately adjacent to the coast was initial, pointing to contemporaneous development based on his dating.[2] Moseley remains convinced that coastal Aspero is the oldest site, and that its maritime subsistence served as a basis for the civilization.[1][22]

Cotton and food sources

[edit]The use of cotton (of the species Gossypium barbadense) played an important economic role in the relationship between the inland and the coastal settlements in this area of Peru. Nevertheless, scholars are still divided over the exact chronology of these developments.[1][13]

Although not edible, cotton was the most important product of irrigation in the Caral–Supe culture, vital to the production of fishing nets (that in turn provided maritime resources) as well as to textiles and textile technology. Haas notes that "control over cotton allows a ruling elite to provide the benefit of cloth for clothing, bags, wraps, and adornment".[13] He is willing to admit to a mutual dependency dilemma: "The prehistoric residents of the Norte Chico needed the fish resources for their protein and the fishermen needed the cotton to make the nets to catch the fish."[13] Thus, identifying cotton as a vital resource produced in the inland does not by itself resolve the issue of whether the inland centers were a progenitor for those on the coast, or vice versa. Moseley argues that successful maritime centers would have moved inland to find cotton.[1]

In a 2018 publication, David G. Beresford-Jones with coauthors have defended Moseley's (1975) Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization (MFAC) hypothesis.[24]

The authors modified and refined the Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization hypothesis of Moseley. Thus, according to them, the MFAC hypothesis now "emerges more persuasive than ever". It was the potential for increased quantities of food production that the cultivation of cotton allowed that was the key in precipitating revolutionary social change and social complexity, according to the authors. Previous to that, the gathering of bast fibers of wild Asclepias was used for fiber production, which was far less efficient.[citation needed]

Beresford-Jones and others also offered further support for their theories in 2021.[25]

History of research

[edit]It was Swiss archaeologist Frédéric Engel, originally, who coined the term "Cotton Preceramic Stage" in 1957 to describe the unusual coastal sites such Norte Chico that had cotton but lacked ceramics and were very ancient. This stage was seen as running for about 1200 years from 3000 to 1800 BC.[26][27]

The development of Caral–Supe is particularly remarkable for the apparent absence of an agricultural staple food. However, recent studies increasingly dispute this and point to maize as a dietary backbone of this and later pre-Columbian civilizations.[28] Moseley found a small number of maize cobs in 1973 at Aspero (also seen in site work in the 1940s and 1950s)[7] but has since called the find "problematic".[22] However, increasing evidence has emerged about the importance of maize in this period:

Archaeological testing at a number of sites in the Norte Chico region of the north central coast provides a broad range of empirical data on the production, processing, and consumption of maize. New data drawn from coprolites, pollen records, and stone tool residues, combined with 126 radiocarbon dates, demonstrate that maize was widely grown, intensively processed, and constituted a primary component of the diet throughout the period from 3000 to 1800 BC.[18]

For Beresford-Jones, his new research on the two nearby ancient coastal settlements of La Yerba, on the east bank of Ica River, Peru (Río Ica) was very important. This is not far from the southern Peruvian town of Ica. The earlier of these settlement was La Yerba II (7571–6674 Cal BP, or ca 5570–4670 BC). When it was occupied, La Yerba II shell midden was situated rather close to the ancient surf line. This was not a permanently occupied site.[24]

A somewhat later site, La Yerba III, on the other hand, was a permanently occupied settlement, and shows a population that was an order of magnitude greater than earlier. Obsidian debitage was abundant at La Yerba III, as opposed to earlier. This suggests an increasing interaction extending to the highlands where obsidian was procured.[24]

The population of La Yerba III already practiced some floodplain horticulture. They cultivated gourds, Phaseolus and Canavalia beans, and plant fiber production was of great importance for their fishing economy. Therefore, they were "pre-adapted to a Cotton Revolution".[24]

Social organization

[edit]

Government

[edit]

The degree of centralized authority is difficult to ascertain, but architectural construction patterns are indicative, at least in certain places at certain times, of an elite population who wielded considerable power: while some of the monumental architecture was constructed incrementally, other buildings, such as the two main platform mounds at Caral,[9] appear to have been constructed in one or two intense construction phases.[13] As further evidence of centralized control, Haas points to remains of large stone warehouses found at Upaca, on the Pativilca, as emblematic of authorities able to control vital resources such as cotton.[1]

Haas suggests that the labour mobilization patterns revealed by the archaeological evidence, point to a unique emergence of human government, one of two alongside Sumer (or three, if Mesoamerica is included as a separate case). While in other cases, the idea of government would have been borrowed or copied, in this small group, government was invented.[citation needed] Other archaeologists have rejected such claims as hyperbolic.[1]

In exploring the basis of possible government, Haas suggests three broad bases of power for early complex societies:[citation needed]

- economic,

- ideology, and

- physical.

He finds the first two present in ancient Caral–Supe.[citation needed]

Economic

[edit]Economic authority would have rested on the control of cotton, edible plants, and associated trade relationships, with power centered on the inland sites. Haas tentatively suggests that the scope of this economic power base may have extended widely: there are only two confirmed shore sites in the Caral–Supe (Aspero and Bandurria) and possibly two more, but cotton fishing nets and domesticated plants have been found up and down the Peruvian coast. It is possible that the major inland centers of Caral–Supe, were at the center of a broad regional trade network centered on these resources.[13]

Citing Shady, a 2005 article in Discover magazine suggests a rich and varied trade life: "[Caral] exported its own products and those of Aspero to distant communities in exchange for exotic imports: Spondylus shells from the coast of Ecuador, rich dyes from the Andean highlands, hallucinogenic snuff from the Amazon."[29] (Given the still limited extent of Caral–Supe research, such claims should be treated circumspectly.) Other reports on Shady's work indicate Caral traded with communities in the jungle farther inland and, possibly, with people from the mountains.[30]

Ideology

[edit]Haas postulates that ideological power exercised by leadership was based on apparent access to deities and the supernatural.[13] Evidence regarding Caral–Supe religion is limited: in 2003, an image of the Staff God, a leering figure with a hood and fangs, was found on a gourd that dated to 2250 BC. The Staff God is a major deity of later Andean cultures, and Winifred Creamer suggests the find points to worship of common symbols of deities.[31][32] As with much other research at Caral–Supe, the nature and significance of the find has been disputed by other researchers.[NB 2]

Mann postulates that the act of architectural construction and maintenance at Caral–Supe may have been a spiritual or religious experience: a process of communal exaltation and ceremony.[23] Shady has called Caral "the sacred city" (la ciudad sagrada)[8] and reports that socio-economic and political focus was on the temples, which were periodically remodeled, with major burnt offerings associated with the remodeling.[33]

Physical

[edit]Haas notes the absence of any suggestion of physical bases of power, that is, defensive construction, at Caral–Supe. There is no evidence of warfare "of any kind or at any level during the Preceramic Period".[13] Mutilated bodies, burned buildings, and other tell-tale signs of violence are absent and settlement patterns are completely non-defensive.[23] The evidence of the development of complex government in the absence of warfare contrasts markedly to archaeological theory, which suggests that human beings move away from kin-based groups to larger units resembling "states" for mutual defense of often scarce resources. In Caral–Supe, a vital resource was present: arable land generally, and the cotton crop specifically, but Mann noted that apparently, the move to greater complexity by the culture was not driven by the need for defense or warfare.[23]

Sites and architecture

[edit]

Caral–Supe sites are known for their density of large sites with immense architecture.[34] Haas argues that the density of sites in such a small area is globally unique for a nascent civilization. During the third millennium BC, Caral–Supe may have been the most densely populated area of the world (excepting, possibly, Northern China).[13] The Supe, Pativilca, Fortaleza, and Huaura River Valleys of Caral–Supe each have several related sites.[citation needed]

Evidence from the ground-breaking work during 1973 at Aspero, at the mouth of the Supe Valley, suggested a site of approximately 13 hectares (32 acres). Surveying of the midden suggested extensive prehistoric construction activity. Small-scale terracing was noted, along with more sophisticated platform mound masonry. As many as eleven artificial mounds were estimated to exist at the site. Moseley calls these "Corporate Labor Platforms", given that their size, layout, and construction materials and techniques would have required an organized workforce.[7]

The survey of the northern rivers found sites between 10 and 100 ha (25 and 247 acres); between one and seven large platform mounds—rectangular, terraced pyramids—were discovered, ranging in size from 3,000 m3 (110,000 cu ft) to more than 100,000 m3 (3,500,000 cu ft).[2] Shady notes that the central zone of Caral, with monumental architecture, covers an area of just greater than 65 hectares (160 acres). Also, six platform mounds, numerous smaller mounds, two sunken circular plazas, and a variety of residential architecture were discovered at this site.[9]

The monumental architecture was constructed with quarried stone and river cobbles. Using reed "shicra-bags", some of which have been preserved,[35] laborers would have hauled the material to sites by hand. Roger Atwood of Archaeology magazine describes the process:

Armies of workers would gather a long, durable grass known as shicra in the highlands above the city, tie the grass strands into loosely meshed bags, fill the bags with boulders, and then pack the trenches behind each successive retaining wall of the step pyramids with the stone-filled bags.[36]

In this way, the people of Norte Chico achieved formidable architectural success. The largest of the platforms mounds at Caral, the Piramide Mayor, measures 160 by 150 m (520 by 490 ft) and rises 18 m (59 ft) high.[9] In its summation of the 2001 Shady paper, the BBC suggests workers would have been "paid or compelled" to work on centralized projects of this sort, with dried anchovies possibly serving as a form of currency.[37] Mann points to "ideology, charisma, and skilfully timed reinforcement" from leaders.[1]

Development and absent technologies

[edit]

When compared to the common Eurasian models of the development of civilization, Caral–Supe's differences are striking. In Caral–Supe, a total lack of ceramics persists across the period. Crops were cooked by roasting.[37] The lack of pottery was accompanied by a lack of archaeologically apparent art. In conversation with Mann, Alvaro Ruiz observes: "In the Norte Chico we see almost no visual arts. No sculpture, no carving or bas-relief, almost no painting or drawing—the interiors are completely bare. What we do see are these huge mounds—and textiles."[1]

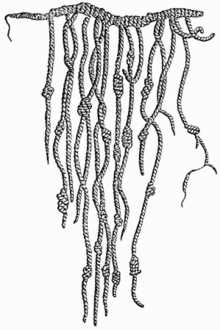

While the absence of ceramics appears anomalous, Mann notes that the presence of textiles is intriguing. Quipu (or khipu), string-based recording devices, have been found at Caral, suggesting a writing, or proto-writing, system at Caral–Supe.[38] (The discovery was reported by Mann in Science in 2005, but has not been formally published or described by Shady.) The exact use of quipu in this and later Andean cultures has been widely debated. Originally, it was believed to be a simple mnemonic technique used to record numeric information, such as a count of items bought and sold. Evidence has emerged, however, that the quipu also may have recorded logographic information in the same way writing does. Research has focused on the much larger sample of a few hundred quipu dating to Inca times. The Caral–Supe discovery remains singular and undeciphered.[39]

Other finds at Caral–Supe have proved suggestive. While visual arts appear absent, the people may have played instrumental music: thirty-two flutes, crafted from pelican bone, have been discovered.[1][29]

The oldest known depiction of the Staff God was found in 2003 on some broken gourd fragments in a burial site in the Pativilca River Valley and the gourd was carbon dated to 2250 BCE.[40] While still fragmentary, such archaeological evidence corresponds to the patterns of later Andean civilization and may indicate that Caral–Supe served as a template. Along with the specific finds, Mann highlights

"the primacy of exchange over a wide area, the penchant for collective, festive civic work projects, [and] the high valuation of textiles and textile technology" within Norte Chico as patterns that would recur later in the Peruvian cradle of civilization."[1]

Academic disputes

[edit]

The magnitude of the Caral–Supe discovery has generated academic controversy among researchers. The "monumental feud", as described by Archaeology, has included "public insults, a charge of plagiarism, ethics inquiries in both Peru and the United States, and complaints by Peruvian officials to the U.S. government".[36] The lead author of the seminal paper of April 2001[9] was a Peruvian, Ruth Shady, with co-authors Jonathan Haas and Winifred Creamer, a married United States team; the co-authoring was reportedly suggested by Haas, in the hopes that the involvement of United States researchers would help secure funds for carbon dating as well as future research funding. Later, Shady charged the couple with plagiarism and insufficient attribution, suggesting the pair had received credit for her research, which had begun in 1994.[29][41]

At issue is credit for the discovery of the civilization, naming it, and developing the theoretical models to explain it. In 1997, Shady described a civilization located on the Supe River, with Caral at its center, although she suggested a larger geographic base for the society.[42]

In 2004, Haas et al. wrote that "Our recent work in the neighboring Pativilca and Fortaleza has revealed that Caral and Aspero were but two of a much larger number of major Late Archaic sites in the Norte Chico", while noting Shady only in footnotes.[2] Attribution of this type is what has angered Shady and her supporters. Shady's position has been hampered by a lack of funding for archaeological research in her native Peru, as well as the media advantages of North American researchers in disputes of this type.[30]

Although Haas and Creamer were cleared of the plagiarism charge by their institutions, the science advisory council of the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History rebuked Haas for press releases and web pages that gave too little credit to Shady and inflated the American couple's role as discoverers.[29]

See also

[edit]- Andean preceramic

- Iperú, Peru tourist information

- List of Norte Chico archaeological sites

- Supe Puerto

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Interior" and "inland" do not refer here to the mountainous interior of Peru proper. All of the Norte Chico sites are broadly coastal, within 100 km (62 mi) of the coast and within the Peruvian littoral (Caral is 23 km [14 mi] inland). "Interior" and "inland" are used here to contrast with sites that are literally adjacent to the ocean.[citation needed]

- ^ Krysztof Makowski, as reported by Mann (1491), suggests there is little evidence that the peoples of Andean civilizations worshipped an overarching deity. The figure may have been carved by a later civilization onto an ancient gourd, as it was found in strata dating between 900 and 1300 AD.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 199–212. ISBN 1-4000-3205-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Haas, Jonathan; Winifred Creamer; Alvaro Ruiz (23 December 2004). "Dating the Late Archaic occupation of the Norte Chico region in Peru". Nature. 432 (7020): 1020–1023. Bibcode:2004Natur.432.1020H. doi:10.1038/nature03146. PMID 15616561. S2CID 4426545.

- ^ a b c "Archaeologists shed new light on Americas' earliest known civilization" (Press release). Northern Illinois University. 22 December 2004. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ^ "The Ancient Andes". History Guild. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "detailed map of Norte Chico sites".

- ^ "Sacred City of Caral-Supe". UNESCO. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d Moseley, Michael E.; Gordon R. Willey (1973). "Aspero, Peru: A Reexamination of the Site and Its Implications". American Antiquity. 38 (4). Society for American Archaeology: 452–468. doi:10.2307/279151. JSTOR 279151. S2CID 163284313. "We see the site as a 'peaking' of an essentially non-agricultural economy. Subsistence was still, basically, from the sea. But such subsistence supported a sedentary style of life, with communities of appreciable size."

- ^ a b Shady Solís, Ruth Martha (1997). La ciudad sagrada de Caral-Supe en los albores de la civilización en el Perú (in Spanish). Lima: UNMSM, Fondo Editorial. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shady Solis, Ruth; Jonathan Haas; Winifred Creamer (27 April 2001). "Dating Caral, a Preceramic Site in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru". Science. 292 (5517): 723–726. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..723S. doi:10.1126/science.1059519. PMID 11326098. S2CID 10172918.

- ^ See CNN, for instance. Given the tentative nature of much research surrounding Norte Chico, readers should be cautious of claims in general news sources.

- ^ "History of Peru". HISTORYWORLD. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- ^ Roberts, J.M. (2004). The New Penguin History of the World (Fourth ed.). London: Penguin Books. pp. 153. ISBN 9780141007236.

[The Americas] are millennia behind the development of civilization elsewhere, whatever the cause of that may be.

"The implied laggardness appears disproven by Norte Chico; in his work, Mann is sharply critical of the inattention provided the Pre-Columbian Americas." - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Haas, Jonathan; Winifred Creamer; Alvaro Ruiz (2005). "Power and the Emergence of Complex Polities in the Peruvian Preceramic". Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. 14 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1525/ap3a.2004.14.037.

- ^ a b Pringle, Heather (27 April 2001). "The First Urban Center in the Americas". Science. 292 (5517): 621. doi:10.1126/science.292.5517.621. PMID 11330310. S2CID 130819896."The claim in this Science 'News of the Week' column that Caral is the oldest urban center in the Americas is highly uncertain."

- ^ Rongxing Guo (2017), Behaviors of Nations. Dynamic Developments and the Origins of Civilizations. ISBN 9783319487724. Springer International Publishing. p. 49

- ^ Ruth Shady Solis (2006), America’s First City? The Case of Late Archaic Caral

- ^ Ruth Shady Solis (2006), America’s First City? The Case of Late Archaic Caral

- ^ a b Haas, J.; Creamer, W.; Huaman Mesia, L.; Goldstein, D.; Reinhard, K.; Rodriguez, C. V. (2013). "Evidence for maize (Zea mays) in the Late Archaic (3000–1800 B.C.) in the Norte Chico region of Peru". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (13): 4945–9. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.4945H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219425110. PMC 3612639. PMID 23440194.

- ^ Moseley, Michael. "The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: An Evolving Hypothesis". The Hall of Ma'at. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Moseley, Michael (1975). The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Menlo Park: Cummings. ISBN 0-8465-4800-3.

- ^ Raymond, J. Scott (1981). "The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: A Reconsideration of the Evidence". American Antiquity. 46 (4). Society for American Archaeology: 806–821. doi:10.2307/280107. JSTOR 280107. S2CID 164171603.

- ^ a b c Sandweiss, Daniel H.; Michael E. Moseley (2001). "Amplifying Importance of New Research in Peru". Science. 294 (5547): 1651–1653. doi:10.1126/science.294.5547.1651d. PMID 11724063. S2CID 9301114.

- ^ a b c d Mann, Charles C. (7 January 2005). "Oldest Civilization in the Americas Revealed". Science. 307 (5706): 34–35. doi:10.1126/science.307.5706.34. PMID 15637250. S2CID 161589785.

- ^ a b c d Beresford-Jones, David; Pullen, Alexander; Chauca, George; Cadwallader, Lauren; García, Maria; Salvatierra, Isabel; Whaley, Oliver; Vásquez, Víctor; Arce, Susana; Lane, Kevin; French, Charles (29 June 2017). "Refining the Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: How Plant Fiber Technology Drove Social Complexity During the Preceramic Period". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 25 (2). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 393–425. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9341-3. ISSN 1072-5369. PMC 5953975. PMID 29782575.

- ^ Beresford-Jones, David G.; Pomeroy, Emma; Alday, Camila; Benfer, Robert; Quilter, Jeffrey; O'Connell, Tamsin C.; Lightfoot, Emma (6 May 2021). "Diet and Lifestyle in the First Villages of the Middle Preceramic: Insights from Stable Isotope and Osteological Analyses of Human Remains from Paloma, Chilca I, La Yerba III, and Morro I". Latin American Antiquity. 32 (4). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 741–759. doi:10.1017/laq.2021.24. ISSN 1045-6635. S2CID 235569923.

- ^ The origins and development of complex society in Andean South America. Archived 2022-03-18 at the Wayback Machine Field Museum – fieldmuseum.org

- ^ Engel, Frederic (1957), "Sites et Etablissements sans Céramique de la Côte Péruvienne." Journal de la Société de Américanistes, Nueva Serie 44: 43–95

- ^ Kinver, Mark (25 February 2013). "Maize was key in early Andean civilisation, study shows". BBC News Online. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Kenneth (September 2005). "Showdown at the O.K. Caral". Discover. 26 (9). Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ a b Belsie, Laurent (January 2002). "Civilization lost?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Hoag, Hanna (15 April 2003). "Oldest evidence of Andean religion found". Nature News (online). doi:10.1038/news030414-4.

- ^ Hecht, Jeff (14 April 2003). "America's oldest religious icon revealed". New Scientist (online). Retrieved 13 February 2007.

- ^ From summary three, Shady (1997)

- ^ Braswell, Geoffrey (16 April 2014). The Maya and Their Central American Neighbors: Settlement Patterns, Architecture, Hieroglyphic Texts and Ceramics. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 978-1317756088.

- ^ White, Nancy. "Archaic/Preceramic (6000–2000 B.C.): Emergence of Sedentism, Early Ceramics". MATRIX. Indiana University Bloomington. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ a b Atwood, Roger (July–August 2005). "A Monumental Feud". Archaeology. 58 (4). Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ a b "Oldest city in the Americas". BBC News. 26 April 2001. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. (12 August 2005). "Unraveling Khipu's Secrets". Science. 309 (5737): 1008–1009. doi:10.1126/science.309.5737.1008. PMID 16099962. S2CID 161448364.

- ^ See 1491, appendix B.

- ^ Hannah Hoag (15 April 2003). "Oldest evidence of Andean religion found". Nature. doi:10.1038/news030414-4.

- ^ "Peruvian archaeologist accuses two US archaeologists of plagiarism". Athena Review (news archive summary). Athena Publications Inc. 22 January 2005. Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ From summary three, Shady (1997): El número de centros urbanos (17), identificado en el valle de Supe, y su magnitud, requirieron de una gran cantidad de mano de obra y de los excedentes, para su edificación, mantenimiento, remodelación y enterramiento. Si consideramos exclusivamente la capacidad productiva de este pequeño valle, esa inversión no habría podido ser realizada sin la participación de las comunidades de los valles vecinos. The number of urban centers (17) identified in the Supe Valley, and their magnitude, requires a great quantity of surplus labor for their construction, maintenance, remodeling and burial. If we consider exclusively the productive capacity of this small valley, this investment could not have been realized without the participation of the communities of neighboring valleys.

Further reading

[edit]- Sandweiss, D. H.; Shady Solís, R.; Moseley, M. E.; Keeferd, D. K.; Ortloff, C. R. (2009). "Environmental change and economic development in coastal Peru between 5,800 and 3,600 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 106 (5): 1359–1363. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.1359S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812645106. PMC 2635784. PMID 19164564.

- Shady, Ruth; Kleihege, Cristopher, eds. (2008). Caral: la primera civilización de América = the first civilization in the Americas. Lima: Universidad de San Martín de Porres. ISBN 978-9972-33-792-5.

- Shady Solís, Ruth (2005). Caral Supe, Perú: the Caral–Supe civilization: 5,000 years of cultural identity in Peru. Lima: Instituto Nacional de Cultura. ISBN 9972-9738-4-0.