Caligula

| Caligula | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

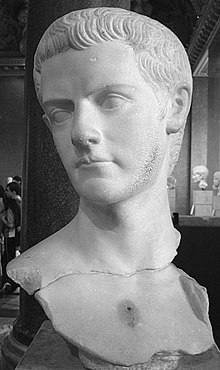

Bust of Gaius Cæsar in the Louvre | |||||

| Reign | 37–41 (Consul from 39) | ||||

| Predecessor | Tiberius | ||||

| Successor | Claudius | ||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| Issue | Julia Drusilla | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Julio-Claudian | ||||

| Father | Germanicus | ||||

| Mother | Agrippina the Elder | ||||

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (August 31, 12 – January 24, 41), more commonly known by his nickname Caligula, was the third Roman Emperor and a member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, ruling from 37 to 41 AD.

As with many emperors, surviving ancient Roman sources on Caligula are scarce. During his brief reign, Caligula focused much of his attention on ambitious construction projects. He annexed Mauretania but failed to conquer Britain. He worked to increase the authority of the principate and struggled to maintain his position against several conspiracies to overthrow him. He was eventually assassinated in 41 by several of his own guards in a conspiracy involving the Roman Senate.

Though Caligula was popular with the Roman public throughout his reign, the scarce surviving sources focus upon anecdotes of his alleged cruelty, extravagance and sexual perversity, presenting him as an insane tyrant.

Family

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| Julio-Claudian dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

|

27 BC – AD 14 |

||

|

AD 14–37 |

||

|

AD 37–41 |

||

|

AD 41–54 |

||

|

AD 54–68 |

||

|

||

Born as Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus on August 31, 12, at the resort of Antium.[1] He was the third of six surviving children born to Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder.[2] Gaius' brothers were Nero and Drusus.[2] His sisters were Julia Livilla, Drusilla and Agrippina the Younger.[2] Gaius was also nephew to Claudius (the future emperor).[3]

Gaius' father, Germanicus, was a prominent member of the Julio-Claudian family and was revered as one of the most beloved generals of the Roman Empire.[4] He was the son of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia Minor. Germanicus was grandson to Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia, as well as the adoptive grandson of Augustus.[5]

Agrippina the Elder was the daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder.[2] She was also a granddaughter of Augustus and Scribonia.[2]

Early life

Travel with his father

As a boy of just two or three, Gaius accompanied his father, Germanicus, on military campaigns in the north of Germania and became the mascot of his father's army.[6] The soldiers were amused that Gaius was dressed in a miniature soldier's uniform, including boots and armor.[6] He was soon given his nickname Caligula, meaning "Little (Soldier's) boots" in Latin, after the small boots he wore as part of his uniform.[7] Gaius, though, reportedly grew to dislike this nickname.[8]

At the age of seven, Caligula also accompanied Germanicus on his expedition to Syria.[9] Upon return, Caligula's father died on October 10, 19. Suetonius claims that Germanicus was poisoned in Syria by an agent of Tiberius who viewed Germanicus as a political rival.[10]

Destruction of his family

After the death of his father, Caligula lived with his mother until relations between her and Tiberius deteriorated.[9] Tiberius would not allow Agrippina to remarry for fear her husband would be a rival.[11] Agrippina and Caligula's brother, Nero Caesar, were banished in 29 on charges of treason.[12][13] The adolescent Caligula was then sent to live first with his great-grandmother, and Tiberius' mother, Livia.[9] Following Livia's death, he was sent to live with his grandmother Antonia.[9] In 30, his brother, Drusus Caesar, was imprisoned on charges of treason and his brother Nero died in exile from either starvation or suicide.[14][13] Suetonius writes that after the banishment of his mother and brothers, Caligula and his sisters were nothing more than prisoners of Tiberius under close watch of soldiers.[15]

Life under Tiberius

In 31, Caligula was remanded to the personal care of Tiberius on Capri, where he lived for six years.[9] A surprise to many, Caligula was spared by Tiberius.[16] According to historians, Caligula was an excellent natural actor and, recognizing danger, hid all his resentment towards Tiberius.[17][9] An observer said of Caligula, "Never was there a better servant or a worse master!"[9][17]

In 33, Tiberius gave Caligula an honorary quaestorship, a position he held until his reign.[18] Meanwhile, both Caligula's mother and brother, Drusus, died in prison.[19][20] Caligula was briefly married to Junia Claudilla in 33, though she died in childbirth the following year.[21] Caligula spent time befriending the Praetorian Prefect, Naevius Sutorius Macro, an important ally.[21] Macro spoke well of Caligula to Tiberius, attemping to quell any ill will or suspicion the Emperor felt towards Caligula.[22]

In 35, Caligula was named joint heir to the throne along with Tiberius Gemellus.[23]

Emperor

Early reign

When Tiberius died on March 16, 37, his estate and the titles of the Principate were left to Caligula and Tiberius' own grandson, Gemellus, who were to serve as joint heirs. Despite Tiberius being 77 and on his death bed, some ancient historians still claim he was murdered.[24][21] Tacitus writes that the Praetorian Prefect, Macro, smothered Tiberius with a pillow to hasten Caligula's accession, much to the joy of the Roman people,[24] and Suetonius writes that Caligula may have carried out the killing.[21] Philo and Josephus, though, record Tiberius dying a natural death.[25] Backed by Macro, Caligula had Tiberius’ will nullified with regards to Gemellus on grounds of insanity, but otherwise carried out Tiberius' wishes.[26]

Caligula accepted the powers of the Principate as conferred by the Senate and entered Rome on March 28 amid a crowd that hailed him as "our baby" and "our star," among other nicknames.[27] Caligula is described as the first emperor who was admired by everyone in "all the world, from the rising to the setting sun."[28] Caligula was loved by many for being the beloved son of the popular Germanicus,[27] but also because he was not Tiberius.[29] It was also said by Suetonius that over one-hundred and sixty thousand animals were sacrificed during three months of public rejoicing to usher in his reign.[30][31] Philo describes the first seven months of Caligula's reign as completely blissful.[32]

Caligula's first acts were said to be generous in spirit, though many were political in nature.[26] To gain support, he granted bonuses to those in the military including the Praetorian Guard, city troops and the army outside of Italy.[26] He destroyed Tiberius' treason papers, declared that treason trials were a thing of the past and recalled exiles.[33] He helped those who had been harmed by the Imperial tax system, banished sex offenders from the empire and put on lavish spectacles for the public, such as gladiator battles.[34][35] Caligula also collected and brought back the bones of his mother and of his brothers and deposited their remains in the tomb of Augustus.[36]

Illness, conspiracies and a change in attitude

Following an auspicious start to his reign, Caligula fell seriously ill in October of 37. Philo is the sole historian to describe this illness,[37] though Cassius Dio mentions it in passing.[38] Philo claims that Caligula’s increased bath-taking, drinking, and sex after becoming emperor caused him to catch the virus.[39] It was said that the entire empire was paralyzed with sadness and sympathy over Caligula’s affliction.[40] Caligula completely recovered from this illness, but Philo highlights Caligula's near-death experience as a turning point in his reign.[41] There is some debate if and when a change in Caligula occurred. Josephus claims that Caligula was a noble and moderate ruler for the first two years of his rule before a turn for the worse occurred.[42]

Shortly after recovering from his illness, Caligula had several loyal individuals killed who had promised their lives for his in the event of a recovery.[43] Caligula had his wife banished and his father-in-law, Marcus Silanus, and his cousin, Tiberius Gemellus, were forced to commit suicide.[44][43]

There is evidence that the deaths of Silanus and Gemellus were prompted by plots to overthrow Caligula. Philo claims Gemellus, in line to become emperor, plotted against Caligula while he was ill.[45] Silanus, prior to killing himself, was formally put on trial by Caligula.[46] Julius Graecinus was ordered to prosecute Silanus, but refused and was executed as well.[46] It is unknown if the plans of Gemellus and Silanus were related or separate. Suetonius claims that the plots were nothing more than Caligula's imagination.[47]

Public reform

In 38, Caligula focused his attention on political and public reform. He published the accounts of public funds, which had not been made public during the reign of Tiberius. He aided those who lost property in fires, abolishing certain taxes and gave out prizes to the public and gymnastic events. He also allowed new members into the equestrian and senatorial orders.[48]

Perhaps most significantly, he restored the practice of democratic elections.[49] Cassius Dio said that this act "though delighting the rabble, grieved the sensible, who stopped to reflect, that if the offices should fall once more into the hands of the many ... many disasters would result".[50]

During the same year, though, Caligula also was criticized for executing people without full trials. The most significant execution was that of Macro, to whom, in many ways, Caligula owed his status as emperor.[38]

Financial crisis and famine

According to Cassius Dio, a financial crisis emerged in 39.[38] Suetonius claims that this crisis began in 38.[51] Caligula’s political payments for support, generosity and extravagance had exhausted the state’s treasury. Ancient historians claim that Caligula began falsely accusing, fining and even killing individuals for the purpose of seizing their estates.[52] A number of other desperate measures by Caligula are described by historians. In order to gain funds, Caligula asked the public to lend the state money.[53] Caligula levied taxes on lawsuits, marriage and prostitution.[54] Caligula began auctioning the lives of the gladiators at shows.[52][55] Wills that left items to Tiberius were interpreted now to leave the items to Caligula.[56] Centurions who had acquired property during plundering were forced to turn over spoils to the state.[56] The current and past highway commissioners were accused of incompetence and embezzlement and forced to repay money.[56]

A brief famine of an unknown size occurred, perhaps caused by this financial crisis. Suetonius claims that it was from public carriages being seized by Caligula.[52] Seneca claims grain imports were disturbed by Caligula using boats for a pontoon bridge.[57]

Construction

Despite financial difficulties, Caligula embarked on a number of construction projects during his reign. Some were for the public good while others were for himself.

Josephus claims Caligula's greatest contribution was having the harbours at Rhegium and Sicily improved which allowed grain imports from Egypt to increase.[58] These improvements may have been in response to the famine.

Caligula completed the temple of Augustus and the theatre of Pompey and began an amphitheatre beside the Saepta.[59] He also had the imperial palace expanded.[60] He began the aqueducts Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus, which Pliny the Elder considered engineering marvels.[61] He built a large racetrack known as the circus of Gaius and Nero and had an Egyptian obelisk (now known as the Vatican Obelisk) transported to Rome by sea and erected in the middle of it.[62] At Syracuse, he repaired the city walls and the temples of the gods.[59] He had new roads built and pushed to keep roads in good condition.[63] He had planned to rebuild the palace of Polycrates at Samos, to finish the temple of Didymaean Apollo at Ephesus and to found a city high up in the Alps.[59] He also planned to dig a canal through the Isthmus in Greece and sent a chief centurion to survey the work.[59]

In 39, Caligula performed a spectacular stunt by ordering a temporary floating bridge to be built using ships as pontoons, stretching for over two miles from the resort of Baiae to the neighboring port of Puteoli.[64] It was said that the bridge was to rival that of Persian King Xerxes' crossing of the Hellespont.[64] Caligula, a man who could not swim,[65] then proceeded to ride his favorite horse, Incitatus, across, wearing the breastplate of Alexander the Great.[64] This act was in defiance of Tiberius' soothsayer Thrasyllus of Mendes prediction that he had "no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding a horse across the Bay of Baiae".[64]

Caligula also had two large ships constructed for himself. These two sunken ships were found at the bottom of Lake Nemi. The ships are among the largest vessels in the ancient world. The smaller of the ships was designed as a temple dedicated to Diana. The larger ship was essentially an elaborate floating palace that counted marble floors and plumbing among its amenities.

Feud with the Senate

In 39, relations between Caligula and the Roman Senate deteriorated.[66] On what they disagreed is unknown. A number of factors, though, aggravated this feud. Prior to Caligula's appointment, The Roman Senate was accustomed to ruling without an emperor in Rome since Tiberius' departure for Capri in 26.[67] Additionally, Tiberius' treason trials had eliminated a number of pro-Julian senators such as Gallus Asinius.[68]

Caligula reviewed Tiberius' records of treason trials and decided that numerous senators, based on their actions during these trials, were not trustworthy.[66] He ordered a new set of investigations and trials.[66] He replaced the consul and had several senators put to death.[69] Suetonius claims that other senators were degraded by being forced to wait on him and run beside his chariot.[69]

Soon after his break with the Senate, Caligula was met with a number of additional conspiracies against him.[70] A conspiracy involving his brother-in-law, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, was foiled in late 39.[70] Soon after, the governor of Germany, Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, was executed for connections to a conspiracy.[70]

Western expansion

In 40, Caligula expanded the Roman Empire into Mauretania and made a significant attempt at expanding into Britannia. The later action was fully realized by his successors.

Mauretania was a client kingdom of Rome ruled by Ptolemy of Mauretania. Caligula invited Ptolemy to Rome and then had him suddenly executed.[71] Mauretania was annexed by Caligula and divided into two provinces.[72] This annexation of Mauretania led to a rebellion of some magnitude that was put down under Claudius.[73] Details on these events are unclear. Cassius Dio had written an entire chapter on the annexation of Mauretania by Caligula, but it is now lost.[74]

There also seemed to be a northern campaign to Britannia that was aborted.[74] This campaign is derided by ancient historians with accounts of Gauls dressed up as Germanic tribesmen at his triumph and Roman troops ordered to collect sea-shells as "spoils of the sea".[75] Due to the lack of sources, what precisely occurred and why is a matter of debate even among the primary sources for Caligula's reign. Modern historians have put forward numerous theories in an attempt to explain these actions. This trip to the English Channel could have merely been a training and scouting mission.[76] The mission may have been to accept the surrender of the British chieftain Adminius.[77] It is possible that his troops refused to embark on a mission across the channel and hence Caligula ordered them to collect seashells as a sarcastic reward.[78] "Seashells", or conchae in Latin, may be a metaphor for something else such as female genitalia (perhaps the troops visited brothels) or boats (perhaps they captured several small British boats).[79]

Acting like a god

In 40, Caligula began implementing very controversial policies that introduced religion into his political role. Caligula began appearing in public dressed as various gods and demigods such as Hercules, Mercury, Venus and Apollo.[80] Reportedly, he began referring to himself as a god when meeting with politicians and he was referred to as Jupiter on occasion in public documents.[81][82] A sacred precinct was set apart for his worship at Miletus in the province of Asia and two temples were erected for worship of him in Rome.[82] The Temple of Castor and Pollux on the Forum was linked directly to the Imperial residence on the Palatine and dedicated to Caligula.[82][83] He would appear here on occasion and present himself as a god to the public.

Caligula's religious policy was a subtle, but important departure from the policy of his predecessors. According to Cassius Dio, living Emperors could be worshiped as divine in the east and dead Emperors could be worshiped as divine in Rome.[84] Augustus also had the public worship his spirit on occasion, but Dio describes this as an extreme act that emperors generally shied away from.[84] Caligula took things a step further and had those in Rome, including Senators, worship him as a physical living god.[85]

Eastern policy

Caligula needed to quell several riots and conspiracies in the eastern territories during his reign. Aiding him in his actions was his good friend, Herod Agrippa, who became governor of the territories of Batanaea and Trachonitis after Caligula became emperor in 37.[86]

The cause of tensions in the east was complicated, involving the spread of Greek culture, Roman law and the rights of Jews. Philo, though, placed the blame with Caligula and claimed that Caligula's desire to be worshiped was at odds with Jewish monotheism.[87] He said that Caligula "regarded the Jews with most especial suspicion, as if they were the only persons who cherished wishes opposed to his."[87]

Caligula did not trust the prefect of Egypt, Aulus Avilius Flaccus. Flaccus had been loyal to Tiberius, had conspired against Caligula's mother and had connections with Egyptian separtists.[88] In 38, Caligula sent Agrippa to Alexandria unannounced to check on Flaccus.[89] According to Philo, the visit was met with jeers from the Greek population who saw Agrippa as the king of the Jews.[90] Flaccus tried to placate both the Greek population and Caligula by having statues of the emperor placed in Jewish synagogues.[91] As a result, riots broke out in city.[92] Caligula responded by removing Flaccus from his position and executing him.[93]

In 39, Agrippa accused Herod Antipas, the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, of planning a rebellion against Roman rule with the help of Parthia. Herod Antipas confessed and Caligula exiled him. Agrippa was rewarded with his territories and now controlled most of Judea. [42]

Riots again erupted in Alexandria in 40 between Jews and Greeks.[94] Jews were accused of not honoring the emperor.[95] Also, disputes occurred in the city of Jamnia.[96] Jews were angered by the erection of a clay altar and destroyed it.[96] In response, Caligula ordered the erection of a statue of himself in the Jewish Temple of Jerusalem.[97]

Fearing civil war if the order were carried out, it was delayed for nearly a year by the governor of Syria, Publius Petronius.[98] Agrippa finally convinced Caligula to reverse the order.[99]

Scandals

Surviving sources present a number of outlandish stories about Caligula that attempt to illustrate cruelty, debauchery and insanity.

The contemporary sources, Philo of Alexandria and Seneca the Younger, describe an insane Emperor who was self-absorbed, angry, killed on a whim and who indulged in too much spending and sex.[100] He is accused of sleeping with other men's wives and bragging about it,[101] killing for mere amusement,[102] purposely wasting money on his bridge, causing starvation,[103] and wanting a statue of himself erected in the Temple of Jerusalem for his worship.[97]

While repeating the earlier stories, the later sources of Suetonius and Cassius Dio add additional tales of insanity. They accuse Caligula of incest with his sisters; Agrippina, Drusilla and Julia Livilla, and say he prostituted them to other men.[104] They claim he sent troops on illogical military exercises.[105][74] They also allege he made the palace into a literal brothel.[106] Perhaps most famous, they say that Caligula tried to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul and a priest.[107]

The validity of these claims is debatable. In Roman political culture, insanity and sexual perversity were often presented hand-in-hand with poor government.[108]

Assassination and aftermath

Caligula's actions as Emperor were described as being especially harsh to the Senate, the nobility and the equestrian order.[109] According to Josephus, these actions led to several failed conspiracies against Caligula.[110] Eventually, a successful murder was planned by officers within the Praetorian Guard led by Cassius Chaerea.[111] The plot is described as having been planned by three men, but many in the Senate, army and equestrian order were said to have been informed of it and involved in it.[112]

According to Josephus, Chaerea had political motivations for the assassination.[113] Suetonius, on the other hand, only claims Caligula called Chaerea derogatory names.[114] Caligula considered Chaerea effeminate because of a weak voice and for not being firm with tax collection.[115] Caligula would mock Chaerea with watchwords like "Priapus" and "Venus".[116]

On January 24, 41, Chaerea and other guardsmen accosted Caligula while he was addressing an acting troupe of young men during a series of games and dramatics held for the Divine Augustus.[117] Details on the events vary somewhat from source to source, but they agree that Chaerea was first to stab Caligula followed by a number of conspirators.[118] Suetonius records that Caligula's death was similar to that of Julius Caesar. He claims that both the elder Gaius Julius Caesar (Julius Caesar) and the younger Gaius Julius Caesar (Caligula) were stabbed 30 times by conspirators led by a man named Cassius (Cassius Longinus and Cassius Charea).[119] By the time Caligula's loyal Germanic guard responded, the emperor was already dead. The Germanic guard, stricken with grief and rage, responded with a rampaging attack on the assassins, conspirators, innocent senators and bystanders alike.[120]

The Senate attempted to use Caligula's death as an opportunity to restore the Republic.[121] Chaerea attempted to convince the military to support the Senate.[122] The military, though, remained loyal to the office of the emperor.[122] The grieving Roman people assembled and demanded that Caligula's murderers be brought to justice.[123] Uncomfortable with lingering imperial support, the assassins sought out and stabbed Caligula's wife, Caesonia, and killed their infant daughter, Julia Drusilla, by smashing her head against a wall.[124] They were unable to reach Caligula's uncle, Claudius, who was spirited out of the city to a nearby Praetorian camp.[125] Claudius became emperor after procuring the support of the Praetorian guard and ordered the execution of Chaerea and any other known conspirators involved in the death of Caligula.[126]

Legacy

Historiography

The history of Caligula’s reign is extremely problematic. Only two sources have surived that were contemporary with Caligula— the works of Philo and Seneca. Philo’s works, On the Embassy to Gaius and Flaccus, give some details on Caligula’s early reign, but mostly focus on events surrounding the Jewish population in Judea and Egypt whom he sympathizes with. Seneca’s various works give mostly scattered anecdotes on Caligula’s personality. Seneca was almost put to death by Caligula in 39 likely due to his associations with conspirators.[127]

At one time, there were detailed contemporary histories on Caligula, but they are now lost. Additionally, the historians who wrote them are described as biased, either overly critical or praising of Caligula.[128] Nonetheless, these lost primary sources, along with the works of Seneca and Philo, were the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Caligula written by the next generations of historians. A few of the contemporary historians are known by name. Fabius Rusticus and Cluvius Rufus both wrote condemning histories on Caligula that are now lost. Fabius Rusticus was a friend of Seneca who was known for historical embelishment and misrepresentation.[129] Cluvius Rufus was a senator involved in the assassination of Caligula.[130] Caligula’s sister, Agrippina the Younger, wrote an autobiography that certainly included a detailed explanation of Caligula’s reign, but it too is lost. Agrippina was banished by Caligula for her connection to Marcus Lepidus, who conspired against Caligula.[131] The inheritance of Nero, Agrippina's son and the future emperor, was seized by Caligula. Gaetulicus, a poet, produced a number of flattering writings about Caligula, but they too are lost.

The bulk of what is known of Caligula comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio, who were both of the Patrician class. Suetonius wrote his history on Caligula eighty years after his death, while Cassius Dio wrote his history over 180 years after Caligula’s death. Though Cassius Dio’s work is invaluable because it alone gives a loose chronology of Caligula’s reign, his surviving work is only a summary written by John Xiphilinus, an 11th century monk.

A handful of other sources also add a limited perspective on Caligula. Josephus gives a detailed description of Caligula’s assassination. Tacitus provides some information on Caligula’s life under Tiberius. Tacitus, the most objective of ancient historians, did write a detailed history of Caligula, but this portion of his Annals is lost. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History also has a few brief references to Caligula.

There are few surviving sources on Caligula and no surviving source paints Caligula in a favorable light. The paucity and bias of sources has resulted in significant gaps in the reign of Caligula. Little is written on the first two years of Caligula’s reign. Additionally, there are only limited details on later significant events, such as the annexation of Mauretania, Caligula’s military actions in Britannia, and his feud with the Roman Senate.

The question of insanity

All surviving sources, except Pliny the Elder, claim Caligula was insane. It is not known whether they are speaking figuratively or literally, though. Additionally, given Caligula's unpopularity among the surviving sources, it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. Recent sources are divided in attempting to ascribe a medical reason for Caligula's behavior, citing as possibilities encephalitis, epilepsy or meningitis. The question of whether or not Caligula was insane remains unanswered.

Philo of Alexandria, Josephus and Seneca also claim Caligula was insane, but claim this madness was a personality trait that came through experience.[42][132][133] Seneca claims that Caligula became arrogant, angry and insulting once becoming emperor and uses his personality flaws as examples his readers can learn from.[134] Josephus claims power made Caligula incredibly conceited and led him to think he was a god.[42] Philo of Alexandria reports that Caligula became ruthless after nearly dying of his illness in 39.[135] Juvenal claims he was given a magic potion that drove him insane.

Epilepsy

Suetonius said that Caligula suffered from "falling sickness" when he was young.[136] Modern historians have theorized that Caligula lived with a daily fear of seizures.[137] Despite swimming being a part of imperial education, Caligula could not swim.[138] Epileptics are encouraged not to swim because light reflecting off water can induce seizures.[139] Additionally, Caligula reportedly talked to the full moon.[140] Epilepsy was also long associated with the moon.[141]

Hyperthyroidism

Some modern historians claim that Caligula suffered from hyperthyroidism.[142] This diagnosis is mainly attributed to Caligula's irritability and his "stare" as described by Pliny the Elder.

Ancestry

| 8. Tiberius Nero | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Nero Claudius Drusus | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Livia Drusilla | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Germanicus | |||||||||||||||

| 10. Mark Antony | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Antonia Minor | |||||||||||||||

| 11. Octavia Minor | |||||||||||||||

| 1.Caligula | |||||||||||||||

| 12. Lucius Vipsanius Agrippa | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa | |||||||||||||||

| 13. ? | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Agrippina the Elder | |||||||||||||||

| 14. Augustus | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Julia the Elder | |||||||||||||||

| 15. Scribonia | |||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 8

- ^ a b c d e Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 7

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.6

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 4

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 1

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 9

- ^ "Caligula" is formed from the Latin word caliga, meaning soldier's boot, and the diminutive infix -ul.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of a Wise Person XVIII 2-5

- ^ a b c d e f g Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 10

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 2

- ^ Tacitus, Annals IV.52

- ^ Tacitus, Annals V.3

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 54

- ^ Tacitus, Annals V.10

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 64

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 62

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals VI.20

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.23

- ^ Tacitus, Annals VI.23

- ^ Tacitus, Annals VI.25

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 12

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius VI.35

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 76

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals VI.50

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius IV.25; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIII.6.9

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.1

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 13

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.10

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 75

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 14

- ^ Philo mentions widespread sacrifice, but no estimation on the degree, Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.12

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.13

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 15

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 16

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 18

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.3

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II–III

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.10

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.14

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius III.16

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius IV.22

- ^ a b c d Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.7.2

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.8

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius V.29

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius V.28

- ^ a b Tacitus, Agricola 4

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 23

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.9–10

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 16.2

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.9.7

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37

- ^ a b c Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 38

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 41

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 40

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.14

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.15

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Shortness of Life XVIII.5

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.5

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 22

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21, Life of Claudius 20; Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXXVI.122

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History XVI.76

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.15; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 19

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 54

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.16; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 30

- ^ Tacitus, Annals IV.41

- ^ Tacitus, Annals' IV.41

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 26

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.22

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 35

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History V.2

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LX.8, LX.24; Pliny the Elder, Natural History V.11

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.25

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 45-47

- ^ P. Bicknell, "The Emperor Gaius' Military Activities in A.D. 40", Historia 17 (1968), 496-505

- ^ R.W. Davies, "The Abortive Invasion of Britain by Gaius", Historia 15 (1996), 124-128; See Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 44

- ^ J.P.V.D. Balsdon, The Emperor Gaius (Caligula) (Oxford, 1934) 90-92; Troops were reluctant to go under Claudius in 43 as well, Cassius Dio, Roman History LX.19

- ^ D. Wardle, Suetonius' Life of Caligula: a Commentary (Brussels, 1994), 313; David Woods "Caligula's Seashells", Greece and Rome (2000), 80-87

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XI-XV

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.26

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.28

- ^ Sanford, J.: "Did Caligula have a God complex?, Stanford Report, September 10, 2003

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History LI.20

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.26-28

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.6.10; Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.25

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XVI.115

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus III.8, IV.21

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.26-28

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.29

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus VI.43

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus VII.45

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus XXI.185

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.8.1

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.8.1

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXX.201

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXX.203

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXXI.213

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.8.1

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Anger xviii.1, On Anger III.xviii.1; On the Shortness of Life xviii.5; Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXIX

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.1

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Anger III.xviii.1

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Shortness of Life xviii.5

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.11, LIX.22; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 24

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 46-47

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 41

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 55; Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.14, LIX.28

- ^ Younger, John G. (2005). Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. pp. p. xvi. ISBN 0415242525.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.1

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56; Tacitus, Annals 16.17; Josephus, Antiquities of Jews XIX.1.2

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.3

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.10, XIX.1.14

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.6

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.5

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 58

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 58; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.14

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 57, 58

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.15; Suetonius, Life of Caligula 58

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2

- ^ a b Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.4.4

- ^ Tacitus, Annals XI.1; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.20

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 59

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.1

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.3.1

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.19

- ^ Tacitus, Annals I.1

- ^ Tacitus, Life of Gnaeus Julius Agricola X, Annals XIII.20

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.13

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.22

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XIII

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Person XVIII.1; Seneca the Younger, On Anger I.xx.8

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Person XVII-XVIII; Seneca the Younger, On Anger I.xx.8

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius III-IV

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 50

- ^ D. Thomas Benediktson, "Caligula's Phobias and Philias: Fear of Seizure?", The Classical Journal (1991) p. 159-163

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Augustus 64, Life of Caligula 54

- ^ J.H. Pearn, "Epilepsy and Drowning in Childhood," British Medical Journal (1977) p. 1510-11

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 26

- ^ O. Temkin, The Falling Sickness (2nd ed., Baltimore 1971) 3-4, 7, 13, 16, 26, 86, 92-96, 179

- ^ R.S. Katz, "The Illness of Caligula" CW 65(1972),223-25, refuted by M.G. Morgan, "Caligula’s Illness Again", CW 66(1973),327-29.

References

Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 59[1]

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, (trans. W.Whiston), Books XVIII–XIX [2]

- Philo of Alexandria, (trans. C.D.Yonge, London, H. G. Bohn, 1854–1890):

- Seneca the Younger

- On Firmness [5]

- On Anger [6]

- To Marcia, On Consolation [7]

- On Tranquility of Mind [8]

- On the Shortness of Life [9]

- To Polybius, On Consolation [10]

- To Helvia, On Consolation [11]

- On Benefits [12]

- On the Terrors of Death (Epistle IV) [13]

- On Taking One's Own Life (Epistle LXXVII) [14]

- On the Value of Advice (Epistle XCIV) [15]

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula[16]

- Tacitus, Annals, Book 6 [17]

Secondary material

- Caligula: the corruption of power by Anthony A. Barrett (Batsford 1989) ISBN 0-7134-5487-3

- Grant, Michael, The Twelve Caesars. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1975

- Hurley, Donna W., An Historical and Historiographical Commentary on Suetonius' "Life of C. Caligula". Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. 1993.

- Biography from De Imperatoribus Romanis

- Biography of Gaius Caligula

- Straight Dope article

- Caligula

- A chronological account of his reign

- A critical account of a number of his reported activities

- His genealogical tree

- Caligula at BBC History

- Official Film Site