Calcium oxalate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Calcium oxalate | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Calcium ethanedioate | |

| Other names

Oxalate of lime

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.419 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CaC2O4 | |

| Molar mass | 128.096 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colourless or white crystals (anhydrous and hydrated forms) |

| Density | 2.20 g/cm3, monohydrate[1] |

| Melting point | 200 °C (392 °F; 473 K) decomposes (monohydrate) |

| 0.61 mg/(100 g) H2O (20 °C)[2] | |

Solubility product (Ksp)

|

2.7 × 10−9 for CaC2O4[3] |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Harmful, Irritant |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302, H312 | |

| P280 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External SDS |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Calcium carbonate Calcium acetate Calcium formate |

Other cations

|

Sodium oxalate Beryllium oxalate Magnesium oxalate Strontium oxalate Barium oxalate Radium oxalate Iron(II) oxalate Iron(III) oxalate |

Related compounds

|

Oxalic acid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Calcium oxalate (in archaic terminology, oxalate of lime) is a calcium salt of oxalic acid with the chemical formula CaC2O4 or Ca(COO)2. It forms hydrates CaC2O4·nH2O, where n varies from 1 to 3. Anhydrous and all hydrated forms are colorless or white. The monohydrate CaC2O4·H2O occurs naturally as the mineral whewellite, forming envelope-shaped crystals, known in plants as raphides. The two rarer hydrates are dihydrate CaC2O4·2H2O, which occurs naturally as the mineral weddellite, and trihydrate CaC2O4·3H2O, which occurs naturally as the mineral caoxite, are also recognized. Some foods have high quantities of calcium oxalates and can produce sores and numbing on ingestion and may even be fatal. Cultural groups with diets that depend highly on fruits and vegetables high in calcium oxalate, such as those in Micronesia, reduce the level of it by boiling and cooking them.[4][5] They are a constituent in 76% of human kidney stones.[6] Calcium oxalate is also found in beerstone, a scale that forms on containers used in breweries.

Occurrence

[edit]Many plants accumulate calcium oxalate as it has been reported in more than 1000 different genera of plants.[7] The calcium oxalate accumulation is linked to the detoxification of calcium (Ca2+) in the plant.[8] Upon decomposition, the calcium oxalate is oxidised by bacteria, fungi, or wildfire to produce the soil nutrient calcium carbonate.[9]

The poisonous plant dumb cane (Dieffenbachia) contains the substance and on ingestion can prevent speech and be suffocating. It is also found in sorrel, rhubarb (in large quantities in the leaves), cinnamon, turmeric and in species of Oxalis, Araceae, Arum italicum, taro, kiwifruit, tea leaves, agaves, Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), and Alocasia and in spinach in varying amounts. Plants of the genus Philodendron contain enough calcium oxalate that consumption of parts of the plant can result in uncomfortable symptoms. Insoluble calcium oxalate crystals are found in plant stems, roots, and leaves and produced in idioblasts. Vanilla plants exude calcium oxalates upon harvest of the orchid seed pods and may cause contact dermatitis.

Calcium oxalate crystals are commonly found in lichens, where they occur in two mineral forms: weddellite (CaC2O4·(2+x)H2O) and whewellite (CaC2O4·H2O). These crystals can form both on the surface of the lichen as a powdery coating called pruina and within the internal structures of the lichen thallus. The type and distribution of these crystals often correlates with environmental conditions: weddellite typically forms in dry environments and can serve as a water source for the lichen, while whewellite is more common in moist habitats. In addition to water regulation, calcium oxalate crystals in lichens serve several protective functions, including shielding against excessive sunlight and potentially helping to neutralize pollutants such as sulfur dioxide. The formation of these crystals is linked to the lichen's ability to dissolve calcium from rocky substrates through the production of oxalic acid, with the amount of calcium oxalate often correlating with the calcium content of the substrate on which the lichen grows.[10]

Calcium oxalate, as ‘beerstone’, is a brownish precipitate that tends to accumulate within vats, barrels, and other containers used in the brewing of beer. If not removed in a cleaning process, beerstone will leave an unsanitary surface that can harbour microorganisms.[11] Beerstone is composed of calcium and magnesium salts and various organic compounds left over from the brewing process; it promotes the growth of unwanted microorganisms that can adversely affect or even ruin the flavour of a batch of beer.

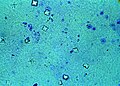

Calcium oxalate crystals in the urine are the most common constituent of human kidney stones, and calcium oxalate crystal formation is also one of the toxic effects of ethylene glycol poisoning.

Chemical properties

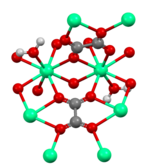

[edit]Calcium oxalate is a combination of calcium ions and the conjugate base of oxalic acid, the oxalate anion. Its aqueous solutions are slightly basic because of the basicity of the oxalate ion. The basicity of calcium oxalate is weaker than that of sodium oxalate, due to its lower solubility in water. Solid calcium oxalate hydrate has been characterized by X-ray crystallography. It is a coordination polymer featuring planar oxalate anions linked to calcium, which also has water ligands.[1]

Medical significance

[edit]Calcium oxalate can produce sores and numbing on ingestion and may even be fatal.

Morphology and diagnosis

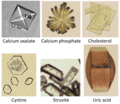

[edit]The monohydrate and dihydrate can be distinguished by the shape of the respective crystals.

- Calcium oxalate dihydrate crystals are octahedral. A large portion of the crystals in a urine sediment will have this type of morphology, as they can grow at any pH and naturally occur in normal urine.

- Calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals vary in shape, and can be shaped like dumbbells, spindles, ovals, or picket fences, the last of which is most commonly seen due to ethylene glycol poisoning.[12]

-

Urine microscopy showing calcium oxalate crystals in the urine. The octahedral crystal morphology is clearly visible.

-

Urine microscopy showing a calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal (dumbbell shaped) and a calcium oxalate dihydrate crystal (envelope shaped) along with several erythrocytes.

-

Urine microscopy showing several calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals (dumbbell shaped, some of them clumped) and a calcium oxalate dihydrate crystal (envelope shaped) along with several erythrocytes.

-

Urinary sediment showing several calcium oxalate crystals. 40X

-

Comparison of different types of urinary stones.

-

Histopathology of calcium oxalate crystals in a benign breast cyst, H&E stain. In the breast, they can be seen on mammography and are usually benign, but can be associated with lobular carcinoma in situ.[13]

Kidney stones

[edit]About 76% of kidney stones are partially or entirely of the calcium oxalate type.[6] They form when urine is persistently saturated with calcium and oxalate. Between 1% and 15% of people globally are affected by kidney stones at some point.[14][15] In 2015, they caused about 16,000 deaths worldwide.[16]

Some of the oxalate in urine is produced by the body. Calcium and oxalate in the diet play a part but are not the only factors that affect the formation of calcium oxalate stones. Dietary oxalate is an organic ion found in many vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Calcium from bone may also play a role in kidney stone formation.

In one study of modulators of calcium oxalate crystallization in urine, magnesium-alkali citrate was shown to inhibit CaOx (calcium oxalate) crystallization, “probably via actions of the citrate, but not the Mg.” This was in comparison to magnesium, citrate, and magnesium citrate. Currently the preparation of magnesium-potassium citrate that was used in one positive study is not available in the United States. [17]

Industrial applications

[edit]Calcium oxalate is used in the manufacture of ceramic glazes.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b S. Deganello (1981). "The Structure of Whewellite, CaC2O4.H2O, at 328 K". Acta Crystallogr. B. 37 (4): 826–829. doi:10.1107/S056774088100441X.

- ^ Haynes, W., ed. (2015–2016). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (96th ed.). CRC Press. p. 4-55.

- ^ Euler. "Ksp Table: Solubility product constants near 25 °C". chm.uri.edu. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Arnold, Michael A. (2014). "Pandanus tectorius S. Parkinson" (PDF). Aggie Horticulture. Texas A&M University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ WebMD Editorial. "Foods High in Oxalates". WebMD. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ a b Singh, Prince; Enders, Felicity T.; Vaughan, Lisa E.; Bergstralh, Eric J.; Knoedler, John J.; Krambeck, Amy E.; Lieske, John C.; Rule, Andrew D. (October 2015). "Stone Composition Among First-Time Symptomatic Kidney Stone Formers in the Community". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (10): 1356–1365. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.016. PMC 4593754. PMID 26349951.

- ^ Francesci, V.R.; Nakata (2005). "Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function". Annu Rev Plant Biol. 56 (56): 41–71. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144106. PMID 15862089.

- ^ Martin, G; Matteo Guggiari; Daniel Bravo; Jakob Zopfi; Guillaume Cailleau; Michel Aragno; Daniel Job; Eric Verrecchia; Pilar Junier (2012). "Fungi, bacteria and soil pH: the oxalate–carbonate pathway as a model for metabolic interaction". Environmental Microbiology. 14 (11): 2960–2970. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02862.x. PMID 22928486.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Parsons, Robert F.; Attiwill, Peter M.; Uren, Nicholas C.; Kopittke, Peter M. (1 April 2022). "Calcium oxalate and calcium cycling in forest ecosystems". Trees. 36 (2): 531–536. doi:10.1007/s00468-021-02226-4. S2CID 239543937.

- ^ Wilk, Karina; Osyczka, Piotr (14 November 2024). "Crystalline deposit in lichens: Determination of crystals with regard to practical application in standard taxonomic studies". Acta Mycologica. 59: 1–11. doi:10.5586/am/193965.

- ^ Ryan, James (27 May 2018). "What is beerstone (and how to remove it)". Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Urine Crystals". ahdc.vet.cornell.edu/. Cornell University. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD.

- Reference for benign/LCIS association: Hind Warzecha, M.D. "Microcalcifications". Pathology Outlines. Last author update: 1 June 2010 - ^ Morgan, Monica S C; Pearle, Margaret S (2016). "Medical management of renal stones". BMJ. 352: i52. doi:10.1136/bmj.i52. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 26977089. S2CID 28313474.

- ^ Abufaraj, Mohammad; Xu, Tianlin; Cao, Chao; Waldhoer, Thomas; Seitz, Christian; d'Andrea, David; Siyam, Abdelmuez; Tarawneh, Rand; Fajkovic, Harun; Schernhammer, Eva; Yang, Lin; Shariat, Shahrokh F. (6 September 2020). "Prevalence and Trends in Kidney Stone Among Adults in the USA: Analyses of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2018 Data". European Urology Focus. 7 (6): 1468–1475. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2020.08.011. ISSN 2405-4569. PMID 32900675. S2CID 221572651.

- ^ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Schwille, P. O.; Schmiedl, A.; Herrmann, U.; Fan, J.; Gottlieb, D.; Manoharan, M.; Wipplinger, J. (1 May 1999). "Magnesium, citrate, magnesium citrate and magnesium-alkali citrate as modulators of calcium oxalate crystallization in urine: observations in patients with recurrent idiopathic calcium urolithiasis". Urological Research. 27 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1007/s002400050097. ISSN 1434-0879. PMID 10424393. S2CID 1506052.

- ^ "Calcium Oxalate Data Sheet". Hummel Croton Inc. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

![Histopathology of calcium oxalate crystals in a benign breast cyst, H&E stain. In the breast, they can be seen on mammography and are usually benign, but can be associated with lobular carcinoma in situ.[13]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/Histopathology_of_a_breast_cyst_with_calcium_oxalate_crystals%2C_annotated.jpg/120px-Histopathology_of_a_breast_cyst_with_calcium_oxalate_crystals%2C_annotated.jpg)