Calabar River

Calabar River | |

|---|---|

Old Calabar Factories from H.M. Stanley, The Congo and the Founding of its Free State; a story of work and exploration (1885) | |

| Coordinates: 4°57′40″N 8°18′28″E / 4.960983°N 8.307724°E | |

| Country | Nigeria |

| State | Cross River State |

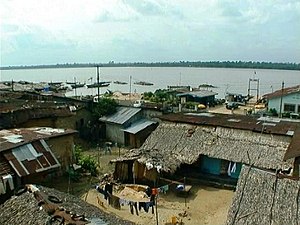

The Calabar River in Cross River State, Nigeria flows from the north past the city of Calabar, joining the larger Cross River about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) to the south. The river at Calabar forms a natural harbor deep enough for vessels with a draft of 6 metres (20 ft).[1]

The Calabar River was once a major source of slaves brought down from the interior to be shipped west in the Atlantic slave trade. Slaving was suppressed by 1860, but the port of Calabar remained important in the export of palm oil and other products, until it was eclipsed by Port Harcourt in the 1920s. With improved roads into the interior, Calabar has regained importance as a port and is growing rapidly. The tropical rain forest in the Calabar River basin is rapidly being destroyed, and pollution is decreasing fish and shrimp catches in the estuary. Those that are caught have unsafe levels of contaminants.

Location

The Calabar River drains part of the Oban Hills in the Cross River National Park.[2] The geology of the river basin includes the Pre-Cambrian Oban Massif, Cretaceous sediments of the Calabar flank and the recent Niger Delta sedimentary basin.[3] The basin is about 43 kilometres (27 mi) wide and 62 kilometres (39 mi) long, with an area of 1,514 square kilometres (585 sq mi)[4] At one time it was entirely covered by tropical rainforest.[5]

The region has a rainy season from April until October, during which 80% of the annual rain falls, with peaks in June and September. Annual rainfall averages 1,830 millimetres (72 in). Average temperatures range from 24 °C (75 °F) in August to 30 °C (86 °F) in February. Relative humidity is high, between 80% and 100%.[3] The basin has 223 streams with a total length of 516 kilometres (321 mi). This is a small number given the size of the basin.[6] Drainage is poor, so the basin is subject to flooding, gully erosion and landslides. A 2010 study said that flooding had increased in recent years.[7]

In 1862 the Zoological Society of London received a description of a new crocodile named Crocodilus frontatus that had been taken from the Old Calabar River, with a much broader head than in Crocodilus vulgaris.[8] A new bat called Sphyrocephalus labrosus was also reported.[9]

The river system formed by the Cross River, Calabar, Great Kwa and other tributaries forms extensive flood plains and wetlands that empty into the Cross River estuary. The system has an estimated area of 54,000 square kilometres (21,000 sq mi) As of 2000 about 8,000 tonnes of fish and 20,000 tonnes of shrimp were being caught annually.[10] Shrimp provide a relatively cheap form of protein to the people of Calabar. The fishermen land their catches at Alepan's beach on the Calabar River, and the catch is sold in the surrounding markets.[11]

Slave trade

The modern city of Calabar was founded by Efik families who had left Creek Town, further up the Calabar river, settling on the east bank in a position where they were able to dominate traffic with European vessels that anchored in the river, and soon becoming the most powerful in the region.[12] In 1767 there was a massacre when the crews of six British slavers intervened in a dispute between the rulers of two competing slaving centers on the river, Old Town and New Town, or Duke's Town: 400 men were killed.[13] Akwa Akpa (Duke's Town) became a center of the trade where slaves were exchanged for European goods.[14]

Due to public petitions against slave trading, the British House of Commons held a hearing on the 1767 massacre in 1790.[15] The British banned the slave trade in 1807 and began to actively intervene in suppressing the trade by ships of other nations. Between 1807 and 1860 the West Africa Squadron seized around 1,600 ships involved in the slave trade.[16] HMS Comus appears to have been the first warship to have sailed up the Calabar River as far as Akwa Akpa in 1815. Her boats captured seven Portuguese and Spanish slavers carrying some 550 slaves.[17]

On 6 January 1829 the Brig Jules was captured by HM Eden on the bar of the Old Calabar River with 220 slaves on board, who had been shipped in the river.[18] On 26 February 1829 the Hirondelle was captured by the Eden within the entrance of the river with 112 slaves on board.[19] On 5 January 1835, boats from HMS Pelorus captured the Spanish polacca-bark Minerva, which was armed with two 18-pounder and two 8-pounder guns. The ship's boats had sailed 60 miles (97 km) up the Calabar river and laid in ambush. Skillful handling resulted in the capture of the slaver with no casualties to the boarding party although the vessel's guns were double-shotted and the crew and the boarding party exchanged small arms fire. The slaver had some 650 slaves aboard.[20]

Later history

With the suppression of the slave trade in the 1850s, palm oil and palm kernels became the main exports of the river. The chiefs of Akwa Akpa placed themselves under British protection in 1884.[21] From 1884 until 1906 Old Calabar was the headquarters of the Niger Coast Protectorate, after which Lagos became the main center.[21] Now called Calabar, the city remained an important port shipping ivory, timber, beeswax, and palm produce until 1916, when the railway terminus was opened at Port Harcourt, 145 km to the west.[22]

Calabar today has regained its importance as a port with the completion of roads providing good access to southeastern Nigeria and western Cameroon. Exports include palm produce, timber, rubber, cocoa, copra, and piassava fibre. Industries include sawmills, a cement factory, boat builders and plants to process rubber, palm oil and food. Artisans make ebony artifacts for the Lagos tourist market. Since 1975 the city has been home to the University of Calabar.[1] The development of the port, and the neighboring Calabar Free Trade Zone and Tinapa Free Zone & Resort has been held back in recent years by bureaucratic problems, and also by poor power supply, poor roads and lack of dredging of the shallow Calabar River channel.[23][24]

Environmental concerns

The city of Calabar is bounded by the Calabar River to the west, Great Kwa River to the east and the wetlands of the Cross river estuary to the south. It can only grow to the north, into the Calabar River catchment area, and this has been happening.[25] The Calabar river watershed was originally covered by tropical rainforest. Much has now been replaced by agriculture, road construction, forestry, industry and housing for the growing population of Calabar.[5] For example, the National Integrated Power Project covers a large area of land besides the Calabar-Itu highway at Ikot Nyong in Odukpani Local Government Area.[25]

A study of changes in land use in the Calabar river catchment between 1967 and 2008 showed that the area covered by high forest decreased by almost 30% during that period. In 1967, high forest covered almost 70% of the basin area. By 2008 it covered less than 40%, mostly in the north. Industrial quarrying began in the 1980s and now affects a significant area. It may be causing stream siltation and flooding as well as air and water pollution.[26] The built-up area more than doubled from 3.5% to 7.6% of the land area in the study period.[27]

Calabar Municipality has no waste treatment facilities. Human wastes and those from cottage industries are dumped in surface sites or into open drains. The torrential rains wash most of the wastes into the Calabar and Great Kwa Rivers.[28] Urban pollution and oil exploration activity in the near shore area both threaten the ecology of the estuary, greatly reducing the numbers and diversity of the species that provide food for shrimps and fish.[29] A 1999 study of fish caught in the Calabar and Kwa rivers and in the estuary showed levels of copper and hydrocarbons were above the World Health Organization permissible levels in all samples. Iron content was above permissible levels in 20% of samples.[30] The rate of accumulation of hydrocarbons was greater in the wet seasons, probably because of higher levels of contaminated material washed from vehicle maintenance shops by the torrential rains.[31]

Calabar Municipality and Calabar South had a combined population of 371,000 in 2006. The population of Cross River State has been growing at the rate of about 3% annually since 1991. Growth rates are considerably higher in Calabar city.[32] The state government faces a serious challenge in accommodating this growth while maintaining income levels and avoiding ecological disaster.[33]

References

- ^ a b Calabar.

- ^ Important Bird Areas...

- ^ a b Eze & Efiong 2010, pp. 19.

- ^ Eze & Efiong 2010, pp. 24.

- ^ a b Efiong 2011, pp. 93.

- ^ Eze & Efiong 2010, pp. 20.

- ^ Eze & Efiong 2010, pp. 18.

- ^ Murray 1862, pp. 213.

- ^ Murray 1862, pp. 8.

- ^ Ekwu & Sikoki 2005, pp. 5.

- ^ Nwosu & Holzohner 1998, pp. 48.

- ^ Leonard 2009, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Sparks 2004, pp. 10ff.

- ^ The Middle Passage.

- ^ Sparks 2004, pp. 26.

- ^ Loosemore 2008.

- ^ Marshall 1835, pp. 129.

- ^ House of Commons 1831, pp. 73.

- ^ House of Commons 1831, pp. 74.

- ^ Correspondence..., pp. 55–58.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911.

- ^ History of Calabar.

- ^ Lack Of Facilities...

- ^ Governor Imoke Urges...

- ^ a b Efiong 2011, pp. 92.

- ^ Efiong 2011, pp. 95.

- ^ Efiong 2011, pp. 98.

- ^ Akpan, Offem & Nya 2006.

- ^ Ekwu & Sikoki 2005, pp. 9.

- ^ Aququo & Udoh 200, pp. 94.

- ^ Aququo & Udoh 200, pp. 95.

- ^ Ottong, Ering & Akpan 2010, pp. 37.

- ^ Ottong, Ering & Akpan 2010, pp. 41.

Sources

- Akpan, E. R.; Offem, J. O.; Nya, A. E. (16 February 2006). "Baseline ecological studies of the Great Kwa River, Nigeria I: Physico-chemical studies". Ecoserve. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Aququo, F.E; Udoh, J.P. (2002). "Patterns of Total Hydrocarbon, Copper and Iron in Some Fish from Cross River Estuary, Nigeria". West African Journal of Applied Ecology. 3. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Calabar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 962.

- Correspondence with the British Commissioners, at Sierra Leone, the Havana, Rio de Janeiro, and Surinam: relating to the slave trade, 1835 ... London: William Clowes and Sons. 1836.

- Efiong, Joel (February 2011). "Changing Pattern of Land Use in the Calabar River Catchment, Southeastern Nigeria". Journal of Sustainable Development. 4 (1). ISSN 1913-9063.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ekwu, A.O.; Sikoki, F.D. (2005). "Species Composition and Distribution of Zooplankton in the Lower Cross River Estuary". African Journal of Applied Zoology and Environmental Biology. 7. ISSN 1119-023X.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eze, Eze Bassey; Efiong, Joel (September 2010). "Morphometric Parameters of the Calabar River Basin: Implication for Hydrologic Processes". Journal of Geography and Geology. 2 (1). ISSN 1916-9787. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Governor Imoke Urges Federal Government to Invest In Tinapa". Cross River State. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- "History of Calabar". The African Executive. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- House of Commons papers. Vol. 19. HMSO. 1831.

- "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Cross River National Park: Oban Division". BirdLife International. 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- "Lack Of Facilities Stall Trade At Calabar Free Trade Zone". Nigerian Pilot. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- Leonard, Arthur Glyn (2009). The Lower Niger and Its Tribes. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 1-113-81057-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loosemore, Jo (8 July 2008). "Sailing against slavery". BBC. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marshall, John (1835). Royal naval biography, or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired-captains, post-captains, and commanders ... Vol. 4. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Murray, Andrew (1862). "Description of Crocodilus Frontatus". Proceedings of the Zoological society of London (1832)., Volume 30. Longman.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nwosu, F.M.; Holzohner, S. (1998). "Lunar and Seasonal Variations in the Catches of Macrovrachium Fisheries of the Cross River Estuary, SE Nigeria" (PDF). Aquatic Commons. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ottong, Joseph G.; Ering, Simon. O.; Akpan, Felix. U. (2010). "The Population Situation in Cross River State of Nigeria and Its Implication for Socio-Economic Development: Observations from the 1991 and 2006 Censuses" (PDF). Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sparks, Randy J. (2004). "Old Calabar and the Massacre of 1767". The two princes of Calabar: an eighteenth-century Atlantic odyssey. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01312-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "The Middle Passage". National Great Blacks in Wax Museum. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.