European Union response to the COVID-19 pandemic

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The COVID-19 pandemic and its spread in Europe has had significant effects on some major EU member countries and on European Union institutions, especially in the areas of finance, civil liberties, and relations between member states.

Outbreak

[edit]

The first European case was reported in France on 24 January 2020.[2]

By 29 May, the EU had 1,105,287 reported cases and 125,431 deaths, which constituted 58% of the cases and 73% of the deaths in Europe according to the ECDC weekly report.[3]

By 6 June, this had increased to 1,131,618 reported cases (56) and 128,247 deaths (76%) according to the ECDC weekly report.[4]

By 18 June, 1,182,368 cases and 130,214 deaths had been reported in the EU, according to ECDC report from Week 25, 14–20 June 2020.[5] The EU agency also monitor KPIs for its UE/EEA+UK members, and found 1,492,177 cases and 72,621 deaths had been reported in the EU/EEA and the UK. The EU agency also monitor KPIs for Europe (a group of more than 50 countries considered as Europe by the ECDC) and found 2,235,109 cases and 184,806 deaths reported as COVID-related in Europe.[5]

By 27 June, 1,216,465 cases and 132,530 deaths had been reported in the EU, according to the ECDC communicable disease threats reports from Week 26, 21–27 June 2020.[6] 1,535,151 cases and 176,020 deaths were reported in the EU/EEA+UK.[6]

By 10 July 2020, 1,274,312 cases and 134,153 deaths had been reported in the EU, according to the ECDC communicable disease threats reports from Week 28, 5–11 July 2020[7] As of 10 July 2020, 179 018 deaths have been reported in the EU/EEA and the UK[7]

According to the Guardian, the EU average infection rate in late June 2020 was around 160 per million inhabitants.[8]

As of 22 December 2024, 186,318,205[9] cases and 1,266,374[9] deaths have been reported in the EU.

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

European Council response

[edit]A video conference was held by the members of the European Council on 10 March 2020, in which President Charles Michel presented four priority areas which the leaders had identified:[10]

- limiting the spread of the virus

- the provision of medical equipment, with a particular focus on masks and respirators

- promoting research, including research into a vaccine

- tackling socio-economic consequences.

At a second video conference on 17 March, a fifth area was added:[11]

- helping citizens stranded in third countries.

At the 17 March video conference, leaders also agreed to place temporary restrictions on non-essential travel to the European Union for a period of 30 days.[11]

At their third video conference on 26 March, Council members vowed to urgently increase capacities for testing for coronavirus infections, in view of WHO recommendations.[12]

On 9 April, finance ministers from the 19 Eurozone countries agreed to provide €240 billion in bailout funds to health systems, €200 billion in credit guarantees for the European Investment Bank, and €100 billion for workers who have lost wages.[13] At their fourth video conference held on 23 April, the European Council endorsed the plan, and called for the package to be operational by 1 June 2020.[14] On the same occasion, the council also tasked the European Commission with taking steps towards the establishment of a recovery fund, the size of which was expected to be at least around €1 trillion. Modalities of the latter fund were still disputed by member states, with France, Italy and Spain leading demands for grants to stricken economies, and Germany strongly favouring loans.[14][15]

On 27 May, the EU Commission proposed a recovery fund dubbed Next Generation EU, with grants and loans for every EU member state accounting for €500 billion and €250 billion respectively. This followed after extensive negotiations in which the so-called "Frugal Four", comprising Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden, had rejected the idea of cash handouts, preferring loans instead. Under the proposal, the money raised on the capital market would be paid back between 2028 and 2058.[16][17] On 21 July, after a four-day negotiation marathon, EU leaders reached a deal in which the core grants component of the recovery fund was reduced from €500 billion to €390 billion, which the loans component was increased to €360 billion, for the same total as in von der Leyen's original proposal. The deal included a governance mechanism that will allow individual member states to raise objections on the usage of financial transfers from Brussels, and to temporarily block these during a review process of governance of the receiving country of three months maximum duration.[18]

Control measures

[edit]Legal context

[edit]According to a publication in Le Monde of 3 members of the University of Michigan, the European health policy relies on three EU pillars:[citation needed]

- the first pillar is the article 168 of the treaty (TFUE) which gives the EU a role in health security, including two agencies such as the ECDC and the drugs agency (OEDT) which were involved in publishing reliable data and avoid medicine starvation;

- the second pillar is the European single market which includes rules to commercialize drugs and medical devices or allow the mobility of health professionals;

- the third pillar being the fiscal governance.

Article 168 plans the Union shall complement national policies, for instance in the "cooperation between the Member States" or adopting recommendations, while the Union shall respect Member States' health policy and organization.[19]

Timeline

[edit]- 9 January: Directorate General for Health and Safety (DG SANTE) opened an alert notification on the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS).

- 17 January: first novel coronavirus meeting for the Health Security Committee

- 28 January: activation of the EU civil protection mechanism for the repatriation of EU citizens.

- 31 January: First funds for research on the new coronavirus.

- 1 February: EU Member States mobilized and delivered a total of 12 tons of protective equipment to China.

- 1–2 February: 447 European citizens brought home from China co-financed by the EU Civil Protection Mechanism.

- 23 February: the Commission co-financed the delivery of more than 25 tonnes of personal protective equipment to China in addition to over 30 tonnes of protective equipment mobilized by EU Member States and already delivered in February 2020.

- 28 February: first procurement for medical equipment jointly with Member States.[2]

- September: plans were announced for a European Health Union to help better prepare the bloc for future pandemics. It could mean more funding and competences for existing programmes such as the EU4Health programme, a reinforced European Medicines Agency and a strengthened European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. There was also a pledge to build a European BARDA to enhance Europe's capacity to respond to future cross-border threats.[20]

European Commission coordination

[edit]Under the principle of conferral, the European Union does not have the legal powers to impose health management policy or actions, such as quarantine measures or closing schools, on member states.[21]

On 21 January 2020, the Platform for European Preparedness Against (Re-)emerging Epidemics (PREPARE) activated its outbreak response "mode 1".[22]

On 28 February 2020, the European Commission opened a tender process for the purpose of purchasing COVID-19 related medical equipment. Twenty member states submitted requests for purchases. A second round procedure was opened on 17 March, for the purchase of gloves, goggles, face protectors, surgical masks and clothing. Poland was among the member states that applied for the second round tender procedure. The European Commission claimed that all the purchases were satisfied by offers. Commissioner Thierry Breton described the procedure as illustrating the power of EU coordination.[21] On 19 March, the EU Commission announced the creation of the rescEU strategic stockpile of medical equipment, to be financed at the level of 90% by the commission, to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.[23]

The Recovery and Resilience Facility is a programme implemented by the European Commission to lessen the economic and social effects of the coronavirus pandemic. [24]

Scientific Advice Mechanism

[edit]The European Union's Chief Scientific Advisors issued a statement on 24 June 2020, providing guidance for how scientific advice should be given and interpreted during the pandemic. One key point made by the Advisors was that scientists must be clearer about the degree of uncertainty that characterises the evolving evidence on which their advice is based, for instance around the use of face-masks. They also emphasised that scientific advice must be separated from decision-making, and this separation must be made clear by politicians.[25]

EU agencies and Directorate-General of the European Commission

[edit]Some EU agencies are involved in the European Union response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[26]

For instance, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), located in Amsterdam, is involved in providing information about the coronavirus pandemic, expediting the development and approval of safe and effective treatments and vaccines, and supporting the continued availability of medicines in the European Union.[27]

ECDC agency

[edit]The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) is the EU agency for disease prevention and control.[citation needed]

It is involved in providing information and risk assessment for the COVID-19 disease for the European Union.[citation needed]

During a two-day meeting, three days before the crisis started in Italy, various countries had different views. Germany had distributed PCR to 20 hospital and performed 1,000 tests, and Italy observed the shortages of PPI in the world market. Austria and Slovakia did not want to make people afraid.[28]

The agency emits weekly bulletins to provide information on the threats it monitors. These bulletins provide the number of cases (by member definitions) and number of deaths in each member state, the EEA, the UK, and most affected countries. It also provides Europe-wide, EU, or EU/EEA+UK aggregates of those numbers.[citation needed]

On 21 May 2020, the ECDC considered that the first wave in 29 out of 31 countries (EU/EEA countries and the UK) had consistently decreasing trends in COVID-19 14-day case notification rates, while the peak of the EU/EEA+UK aggregate was on 9 April 2020.[29]

Before 22 May, the ECDC, the EASA, and ECDC director Andrea Ammon believed a second wave could occur, because the number of cases reported in May was greater than the number of cases reported in January/February.[30][31]

On 28 May 2020, the ECDC published a methodology to help public health authorities in the EU/EEA Member States and the UK estimate point prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection by pooled RT-PCR testing, rather than reporting individual cases (which underestimated the spread of the virus).[32]

Andrea Ammon believed that the return from ski holidays in the Alps during the first week of March could be seen as a significant time in the spread of disease in Europe.[31]

Risk assessment in the EU/EEA and UK

[edit]On 13 March 2020, the following COVID-19 related risks were assessed by the ECDC:[33]

| Risk | Level |

|---|---|

| risk of severe disease associated with COVID-19 infection for people in the EU/EEA and UK: general population | moderate |

| risk of severe disease associated with COVID-19 infection for people in the EU/EEA and UK: older adults and individuals with chronic underlying conditions | high |

| risk of milder disease, and the consequent impact on social and work-related activity, | high |

| risk of the occurrence of sub-national community transmission of COVID-19 in the EU/EEA and the UK | very high |

| risk of occurrence of widespread national community transmission of COVID-19 in the EU/EEA and the UK in the coming weeks | high |

| risk of healthcare system capacity being exceeded in the EU/EEA and the UK in the coming weeks | high |

| risk associated with transmission of COVID-19 in health and social institutions with large vulnerable populations | high |

Recommendations for safe resumption of railway services in Europe

[edit]The European Union Agency for Railways (ERA), the European Commission, and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have developed a COVID-19 railway protocol.[34]

The recommendations in the protocol address issues such as Physical distancing, Use of face masks, Respiratory etiquette, Hand hygiene, Case management on board a train, Contact Tracing, Thermal Screening.[34]

Eurostat

[edit]Eurostat, a Directorate-General of the European Commission, published some data related to the COVID-19 response:

- The number of air passengers halved in March 2020 in 13 EU member states: Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Croatia, Italy (see country note), Cyprus, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland, including a decrease of 10 000 000 in Germany[35]

- The increase of automatic data processing machines import from China (+€884 billion, +33%) and articles of apparel of textile fabrics (+€129 billion, +36%)[36]

Border management

[edit]External border management

[edit]EU leaders condemned the U.S. decision to restrict travel from Europe to the United States. European Council President Charles Michel and Ursula von der Leyen said in a joint statement: "The European Union disapproves of the fact that the US decision to impose a travel ban was taken unilaterally and without consultation."[37]

On 16 March, the EU Commission said that member states should recommend that their citizens remain within the EU to avoid spreading the virus in other countries.[38]

Under EU harmonization, France and Germany planned to reopen their internal (Schengen) borders on 15 June and their external border on 1 July.[39]

As of late June, the EU was considering admitting travelers from 15 countries: Algeria, Australia, Canada, China, Georgia, Japan, Montenegro, Morocco, New Zealand, Rwanda, Serbia, South Korea, Thailand, Tunisia and Uruguay.[40] They planned to reopen borders to these travelers on 1 July.[citation needed]

Border management with the UK

[edit]The UK left the EU on 31 January but remained part of the bloc's single market during the transition period. This allowed coordination with the British government, without British involvement in the EU's internal deliberations.[citation needed]

Ireland and the UK benefit from a 14-day quarantine due to the UK's high infection rate.[8]

Border management with micro-states

[edit]Andorra, Vatican City, Monaco and San Marino were to benefit from the easing of the EU's travel restrictions.[8]

Internal border management

[edit]In February and early March 2020, the EU rejected the idea of suspending the Schengen free travel zone and introducing border controls with Italy.[41][42] [43]

After Slovakia, Denmark, the Czech Republic and Poland announced complete closure of their national borders, the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said by 12 March that "Certain controls may be justified, but general travel bans are not seen as being the most effective by the World Health Organization. Moreover, they have a strong social and economic impact, they disrupt people’s lives and business across the borders."[44]

On 28 May 2020, a Health Security Committee reports on COVID-19 outbreak suggest appropriate testing strategies is needed before starting the exit strategy. De-escalation of travel restrictions is wished to be coordinated at EU level. The questions related to the Schengen zone and movement within the EU is also in the scope of the Commission and Member States in the HOME Affairs group, and the ECDC. In the same time, an EU support for vaccination plan is under work.[45]

In early June 2020, Ylva Johansson, EU's home affairs commissioner, reported most member states prefer strongly an additional short prolongation of the internal travel ban. Lifting is planned to be gradual, in July.[46]

Under EU harmonization, France and Germany will reopen their internal (Schengen) borders on 15 June while their external border should be reopened on 1 July.[39]

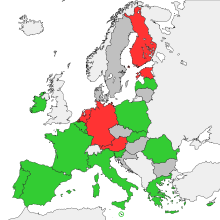

During the summer, differences appeared between member states in their capacity to perform tests and in their test results, with 2 to 176 cases per 100 000 inhabitants, for a 46 average. European parliament would like to avoid the lead to internal border closures.[47] COVID-19: harmoniser les procédures et la fréquence des tests dans l’UE | Actualité | Parlement européen

Repatriations from outside the EU

[edit]On 29 May, repatriation flights under the Union Civil Protection Mechanism led to 83,956 repatriations: 74,673 EU citizens and 9,283 non-EU citizens.[48]

Assistance to member states

[edit]Common debt and European Central Bank response

[edit]In July 2020, the European Council agreed upon the Next Generation EU (NGEU) recovery package to support member states hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic with a 750 billion € fund to be added to the 2021-2027 budget of the EU.[49] As the fund will draw support from large-scale issuance of European sovereign bonds it will be a breakthrough to a unified European fiscal policy. The fund will be paid off by generating own resources through direct taxation.[50] A covid recovery package worth €750 billion was laid by the European Union, as part of its budget, in November 2020. However, its endorsement was delayed to December as Hungary and Poland vetoed during a couple of days the budget due to the connection of EU funds to respect for the rule of law.[51][52]

ECB proposal

[edit]On 18 March 2020, the European Central Bank (ECB), headed by Christine Lagarde, announced the purchase of an additional €750 billion of European corporate and government bonds for the year.[53] Lagarde urged the national governments of the member states to seriously consider a one-off joint debt issue of coronabonds.[54][55]

By early April, the ECB announced its intention to push back strategy review from a late 2020 target to the middle of 2021.[56]

Former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi stated that member states should absorb coronavirus losses, rather than the private sector. He compared the impact of coronavirus to World War I.[54]

Coronabonds controversy

[edit]

The Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez stated that "If we don't propose now a unified, powerful and effective response to this economic crisis, not only the impact will be tougher, but its effects will last longer and we will be putting at risk the entire European project", while the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte commented that "the whole European project risks losing its raison d'être in the eyes of our own citizens".[57]

Debates over how to respond to the epidemic and its economic fallout have opened up a rift between Northern and Southern European member states, reminiscent of debates over the 2010s European debt crisis.[58] Nine EU countries—Italy, France, Belgium, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia and Luxembourg—called for "corona bonds" (a type of eurobond) to help their countries to recover from the epidemic, on 25 March. Their letter stated, "The case for such a common instrument is strong, since we are all facing a symmetric external shock."[59][60] Northern European countries such as Germany, Austria, Finland, and the Netherlands oppose the issuing of joint debt, fearing that they would have to pay it back in the event of a default. Instead, they propose that countries should apply for loans from the European Stability Mechanism.[61][62] A similar position by the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden was nicknamed by the press as the "Frugal Four". Corona bonds were discussed on 26 March 2020 in a European Council meeting, which was three hours longer than expected due to the "emotional" reactions of the prime ministers of Spain and Italy.[63][54] Unlike the European debt crisis—partly caused by the affected countries—southern European countries did not cause the coronavirus pandemic, therefore eliminating the appeal to national responsibility.[61]

Vaccines

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Very incomplete and unsourced coverage of EU vaccines, does not mention Moderna for example. (March 2021) |

In July 2020 the European Union refused an offer of 500 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer-BioNTech due to its pricing.[64]

In January 2021, the EU changed their mind and bought 300 million BioNTech-Pfizer vaccine doses and considered buying 300 million more.[65] 75 million doses were expected to be available during the second quarter of 2021, the remaining doses would be available during the second half of 2021.[citation needed]

The EU has ordered vaccines from AstraZeneca. Problems with delivery thereof led to the European Commission–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine dispute.[citation needed]

On 1 December 2021, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that EU nations should consider making COVID-19 vaccinations mandatory because too many people were refusing to get shots voluntarily.[66]

Cooperation between member states

[edit]Several actions are performed by many EU countries to help other EU countries.[67][68]

From 4 to 19 March, Germany banned the export of personal protective equipment,[69][70] and France also restricted exports of medical equipment, drawing criticism from EU officials who called for solidarity.[71] Many Schengen Area countries closed their borders to stem the spread of the virus.[72]

EuroMoMo project

[edit]The number of reported deaths does not provide best accuracy on pandemic fatalities, because some countries use slightly different ways to report those deaths.[citation needed]

To avoid such discrepancies, a fatalities excess observatory named "European Mortality Monitoring" (EuroMomo) is weekly operated by Statens Serum Institute epidemiologists with data from 28 partners, from 24 countries.[73]

This project uses standardized methods to ease international comparisons.[citation needed]

Lasse Vestergaard considers that deaths excess estimations are the best way to monitor COVID-19 fatalities. The EuroMoMo project computes a z-score number to rank those deaths excess.[73]

To prepare for future pandemics, the European Union is launching a new initiative called the European Bio-Defense Preparedness Plan. The Health Emergency and Response Authority (HERA) Incubator was established in February 2021, following a conference of European chiefs of state. The initiative intends to focus on collaboration between states.[74][75][76]

Controversies

[edit]European External Action Service self-censorship controversy

[edit]The European External Action Service, charged with combating disinformation from Russia and China, produced an initial status update report on 1 April in which highlighted China's attempts to manipulate the narrative. It asserted that Chinese state media and government officials were promoting "unproven theories about the origin of COVID-19", as well as emphasizing "displays of gratitude by some European leaders in response to Chinese aid".[77] The original report had said that there was evidence of a "continued and coordinated push by official Chinese sources to deflect any blame".[77]

It was revealed that wording was amended under pressure from China to say: “We see a continued and coordinated push by some actors, including Chinese sources, to deflect any blame”, and that according to The New York Times the office of the High Representative of the European Union, Josep Borrell, intervened to delay the release of the initial report to secure the desired change of wording.[77] The scandal of self-censorship ensued after an email from a staff member EEAS which warned that the softening of the report would "set a terrible precedent and encourage similar coercion in the future", had been leaked to the New York Times.[78][79] Borrell ordered an internal investigation into the leak.[78]

Hungary emergency legislation

[edit]Sixteen member nations of the European Union issued a statement, warning that certain emergency measures issued by countries during the coronavirus pandemic could undermine the principles of rule of law and democracy on 1 April. They announced that they "support the European Commission initiative to monitor the emergency measures and their application to ensure the fundamental values of the Union are upheld."[80] The statement does not mention Hungary, but observers believe that it implicitly refers to a Hungarian law granting plenary power to the Hungarian Government during the coronavirus pandemic. The following day, the Hungarian Government joined the statement.[81][82]

The Hungarian parliament passed the law granting plenary power to the Government by qualified majority, 137 to 53 votes in favour, on 30 March 2020. After promulgating the law, the President of Hungary, János Áder, announced that he had concluded that the time frame of the Government's authorisation would be definite and its scope would be limited.[83][84][85][86] Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, stated that she was concerned about the Hungarian emergency measures and that it should be limited to what is necessary and Minister of State Michael Roth suggested that economic sanctions should be used against Hungary.[87][88]

The heads of thirteen member parties of the European People's Party (EPP) made a proposal to expunge the Hungarian Fidesz for the new legislation on 2 April. In response, Viktor Orbán expressed his willingness to discuss any issues relating to Fidesz's membership "once the pandemic is over" in a letter addressed to the Secretary General of EPP Antonio López-Istúriz White. Referring to the thirteen leading politicians' proposal, Orbán also stated that "I can hardly imagine that any of us having time for fantasies about the intentions of other countries. This seems to be a costly luxury these days."[89] During a video conference of the foreign ministers of the European Union member states on 3 April 2020, Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Péter Szijjártó, asked for the other ministers to read the legislation itself not its politically motivated presentations in newspapers before commenting on it.[90]

Resignation of Phil Hogan

[edit]In light of the Oireachtas Golf Society scandal, Phil Hogan resigned as EU Trade Commissioner on 26 August 2020.[91][92]

Public opinion

[edit]

European Council on Foreign Relations survey

[edit]A survey performed in April by the European Council on Foreign Relations showed that most European citizens have perceived the EU as irrelevant wishing more EU cooperation, according to The Guardian.[93]

In France, 58% perceived the EU as irrelevant, while 61% perceived the Macron government had under-performed.[93]

Survey commissioned by the European Parliament

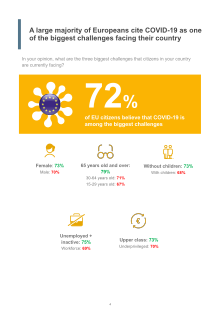

[edit]In July 2020 was published a Public Opinion Survey Commissioned by the European Parliament with 24,798 interviews.[94]

- "The EU should have more to competences to deal with crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic?" 68% agree

- "The EU should have greater financial means to be able to overcome the consequences of the Coronavirus pandemic" 56%

- "How satisfied or not are you with the solidarity between EU Member States in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic?" 39% Satisfied, 53% Not satisfied.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Lessons From Slovakia—Where Leaders Wear Masks". The Atlantic. 13 May 2020. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Timeline of EU action". European Commission – European Commission. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "COMMUNICABLE DISEASE THREATS REPORT" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Communicable disease threats report, 31 May -6 June 2020, week 23". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b "COMMUNICABLE DISEASE THREATS REPORT" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 September 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ a b "COMMUNICABLE DISEASE THREATS REPORT" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ a b "COMMUNICABLE DISEASE THREATS REPORT" (PDF). ecdc. July 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Boffey, Daniel (29 June 2020). "US visitors set to remain banned from entering EU". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b Mathieu, Edouard; Ritchie, Hannah; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Dattani, Saloni; Beltekian, Diana; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (2020–2024). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ "Video conference of the members of the European Council, 10 March 2020". Council of the European Union. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Video conference of the members of the European Council, 17 March 2020". Council of the European Union. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Video conference of the members of the European Council, 26 March 2020". Council of the European Union. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Eurogroup Strikes Half-Trillion Euro Deal to Help Members Cope with COVID-19 | Voice of America – English". Voice of America. 10 April 2020. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Conclusions of the President of the European Council following the video conference of the members of the European Council, 23 April 2020". Council of the European Union. 23 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Sam; Khan, Mehreen; Brunsden, Jim; Chazan, Guy (23 April 2020). "Germany throws weight behind massive EU recovery fund". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.(subscription required)

- ^ "Coronavirus: Von der Leyen calls €750bn recovery fund 'Europe's moment'". BBC. 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Europe's moment: Repair and prepare for the next generation". European Commission. 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Brunsden, Jim; Fleming, Sam; Khan, Mehreen (21 July 2020). "EU recovery fund: how the plan will work". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Article 168 of the treaty, points 1, 2, 6 and 7

- ^ Pitchers, Christopher (18 September 2020). "EU plans for health union to boost pandemic preparedness". euronews. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ a b Pańkowska, Maria (26 March 2020). "Szumowski krytykuje UE: 'Nie ma tej europejskiej solidarności'. To wielopiętrowy fałsz". OKO.press. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

Bo jak byśmy czekali na inne kraje, na Europę, na świat, to byśmy się obudzili bez środków, a dookoła wszyscy by te środki sobie zakupili ... Żeby była jasność, to nie jest tak, że my ten sprzęt mamy w Europie, że są jego nieograniczone ilości. ... Bo niestety tutaj centralne zakupy zawiodły, nie ma tej europejskiej solidarności.

- ^ Tidey, Alice (21 January 2020). "Coronavirus: How is the EU preparing for an outbreak, and why screening may be futile". Euronews. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19: Commission creates first ever rescEU stockpile of medical equipment". European Commission. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (27 July 2022). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions in 2021. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5369-3. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ Statement on scientific advice to European policy makers concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. Publications Office of the European Union. 2018. ISBN 9789276199212. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "EAHP COVID-19 Resource Centre | European Association of Hospital Pharmacists". eahp.eu. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". European Medicines Agency. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Güell, Oriol (18 May 2020). "Los guardianes de la salud europea subestimaron el peligro del virus". EL PAÍS. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Surveillance report". covid19-surveillance-report.ecdc.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus : alors que le bilan mondial dépasse les 328 000 morts, l'épidémie s'aggrave en Amérique du Sud". Le Monde. 21 May 2020. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b Ryckmans, Grégoire (21 May 2020). "L'Europe doit se préparer à une deuxième vague mais elle ne sera pas nécessairement désastreuse, selon la responsable européenne du coronavirus". RTBF. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Measures for travellers" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Daily risk assessment on COVID-19, 13 March 2020". Europa (web portal). 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Rail protocol" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Impact of COVID-19 on air passenger transport". European Commission. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Impact of the COVID-19 on EU trade with China". European Commission. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "EU condemns Trump travel ban from Europe as virus spreads". Associated Press (AP). 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Transparency" (PDF). European Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus : " Situation inquiétante " au Brésil, reconfinement dans des quartiers de Pékin". Le Monde. 12 June 2020. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael (26 June 2020). "Europe prepares to reopen to foreign travelers, but Americans don't even figure into the discussion". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: EU rules out Schengen border closures amid Italy outbreak". Deutsche Welle. 24 February 2020. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Commission chief warns against unilateral virus travel bans". EURACTIV. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Current Response and Management Decisions of the European Union to the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Review". Sustainability 2020, 12, 3838. 8 May 2020. doi:10.3390/su12093838.

- ^ "Denmark, Poland and Czechs seal borders over coronavirus". Financial Times. 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Preparedness response" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "Global report: EU pledges to lift internal border controls by end of month". The Guardian. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ /covid-19-harmoniser-les-procedures-et-la-frequence-des-tests-dans-l-ue

- ^ "Repatriation flights" (PDF). Europa (web portal). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Special meeting of the European Council, 17-21 July 2020 – Conclusions Archived 21 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Special European Council, 17-21 July 2020 - Main results Archived 18 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ "Hungary and Poland block EU coronavirus recovery package". Politico. 16 November 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "EU budget blocked by Hungary and Poland over rule of law issue". BBC News. 16 November 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Jones, Erik (8 April 2020). "Old Divisions Threaten Europe's Economic Response to the Coronavirus". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "What are 'corona bonds' and how can they help revive the EU's economy?". euronews. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Germans and Dutch set to block EU 'corona bonds' at video summit". Euractiv. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Goldstein, Steve (2 April 2020). "ECB pushes back strategy review". Marketwatch. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "EU will lose its 'raison d'etre' if it fails to help during COVID-19 crisis, Italy's PM warns". 28 March 2020. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Keith (30 March 2020). "Fighting Pandemic, Europe Divides Again Along North and South Lines". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Amaro, Silvia (25 March 2020). "Nine European countries say it is time for 'corona bonds' as virus death toll rises". CNBC. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "The EU can't agree on how to help Italy and Spain pay for coronavirus relief". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Italy's future is in German hands". Politico. 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Bayer, Lili (1 April 2020). "EU response to corona crisis 'poor,' says senior Greek official". Politico. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Virtual summit, real acrimony: EU leaders clash over 'corona bonds'". Politico. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "How the EU's Covid-19 vaccine rollout became an 'advert for Brexit'". France24. 6 February 2021. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "EU 'should consider mandatory vaccination', says von der Leyen". euronews. 1 December 2021. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus: la solidarité européenne à l'œuvre". Commission européenne – European Commission. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ STAS, Magali (26 March 2020). "Réaction commune de l'UE face à la pandémie de COVID-19". Union Européenne. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Germany bans export of medical protection gear due to coronavirus". Reuters. 4 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Germany lifts export ban on medical equipment over coronavirus". Reuters. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Tsang, Amie (7 March 2020). "E.U. Seeks Solidarity as Nations Restrict Medical Exports". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus Is a Critical Test for the European Union". Time. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ a b Mathiot, Cédric; Leboucq, Fabien (26 April 2020). "L'étude de la surmortalité donne-t-elle les vrais chiffres du Covid-19, au-delà des bilans officiels ?". Libération. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Access to COVID-19 vaccines: Global approaches in a global crisis". OECD. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Commission launches European Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) – uemo". Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (27 January 2022). EIB Activity Report 2021. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5108-8. Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "EU toned down Chinese disinformation report after it threatened 'repercussions'". South China Morning Post. 25 April 2020. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b Burchard, Hans von der (27 May 2020). "EU's diplomatic service launches probe over China disinformation leak". Politico. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Apuzzo, Matt (24 April 2020). "Pressured by China, E.U. Softens Report on Covid-19 Disinformation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "Statement by Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden". 1 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Trolldiplomácia a maximumon: A magyar kormány is csatlakozott a jogállamiságot védő európai nyilatkozathoz". 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "A magyar kormány is csatlakozott ahhoz a kiálláshoz, ami kimondatlanul ugyan, de ellene szól". 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Megvolt a kétharmad, a kormánypárti többség megszavazta a felhatalmazási törvényt". 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "A Fidesz-kétharmad elfogadta a felhatalmazási törvényt". 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Megszavazta az Országgyűlés a koronavírus-törvényt, Áder pedig ki is hirdette". 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Áder János már alá is írta a felhatalmazási törvényt". 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "EU executive chief concerned Hungary emergency measures go too far". 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020.

- ^ "EU sanctions over Hungary's virus measures should be considered, German official says". 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Orbán a Néppártnak: Most nincs időm erre!". 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Szijjártó looked virtually into the eyes of his critics". 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020.

- ^ Connelly, Tony (26 August 2020). "Phil Hogan resigning from role as EU Commissioner". RTÉ News and Current Affairs. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Ní Aodha, Gráinne; Byrne, Laura; Murray, Sean (26 August 2020). "Phil Hogan is to resign from his role as EU Trade Commissioner". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b Butler, Katherine (24 June 2020). "Coronavirus: Europeans say EU was 'irrelevant' during pandemic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.