Exhibition Stadium

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

Exhibition Stadium CNE Stadium The Ex | |

Exhibition Stadium in 1988 | |

| |

| Location | Lake Shore Boulevard West & Ontario Drive Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43°37′55″N 79°25′4″W / 43.63194°N 79.41778°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | City of Toronto |

| Operator | City of Toronto |

| Capacity | 20,679 (1948)[1] 33,150 (1959–1974 football) 41,890 (1975 football) 54,741 (1976–1988 football) 38,522 (1977 baseball) 43,737 (1978–1989 baseball) |

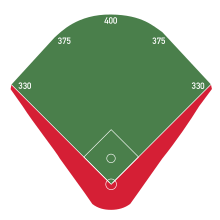

| Field size | Left Field – 330 ft (101 m) Left-Centre – 375 ft (114 m) Centre Field – 400 ft (122 m) Right-Centre – 375 ft (114 m) Right Field – 330 ft (101 m) Backstop – 60 ft (18 m)  |

| Surface | Grass (1959–1971) AstroTurf (1972–1989) |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1948 (grandstand) 1959 (football bleachers) 1976 (football and baseball seats) |

| Opened | August 5, 1959 |

| Closed | 1996 |

| Demolished | January 31, 1999 |

| Construction cost | $3 million (1948 north grandstand)[1] $650,000 (1959 south bleachers)[1] $17.5 million (1976 renovations)[2] |

| Architect | Marani and Morris (1948) Bill Sanford (1976) |

| Tenants | |

| Toronto Argonauts (CFL) (1959–1988) Serbian White Eagles (NSL) (1973–1974) Toronto Blue Jays (MLB) (1977–1989) Toronto Blizzard (NASL) (1979–1983) | |

Canadian National Exhibition Stadium (commonly known as Exhibition Stadium or CNE Stadium and nicknamed The Ex[3]) was a multi-purpose stadium in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on the grounds of Exhibition Place. Originally built for Canadian National Exhibition events, the stadium served as the home of the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League (CFL) from 1959 to 1988, the Toronto Blue Jays of Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1977 to 1989, and the Toronto Blizzard of the North American Soccer League (NASL) from 1979 to 1983.[4][5] The stadium hosted the Grey Cup game 12 times over a 24-year period.

The grandstand (known as CNE Grandstand) was used extensively throughout the summer months for hosting concerts.[6]

In 1999, the stadium was demolished and the site was used for parking until 2006. BMO Field was built on the site in 2007 roughly where the northern end of the covered grandstand once stood.

History

[edit]CNE Grandstand

[edit]Exhibition Stadium was the fourth stadium to be built on its site since 1879.[1] When the original grandstand was lost due to a fire in 1906, it was quickly rebuilt.[1] A second fire destroyed the stadium in April 1946, which led to the city constructing a covered north-side grandstand (known as CNE Grandstand) for CA$3.5 million in 1948.[7][8][9][10][11] This part of the stadium's structure stayed even as the stadium underwent various changes to its configuration over the years until its 1999 closure.

The new building seated 22,000, 6,000 more than the previous grandstand. The building held two dining halls that could seat 1,000, a 1,500 square feet (140 m2) Exhibition Hall, electric plant and storage facilities. It was designed by firm Marani and Morris, and built by Piggott Construction. It had a large 300 feet (91 m)-wide stage and three radio rooms for broadcasting. The roof had a total of 300 floodlights and spotlights. The roof was specially designed to provide no place for pigeons to roost.[12]

Expansion for CFL football

[edit]When the Toronto Argonauts moved from Varsity Stadium for the 1959 season, a smaller CA$650,000 bleacher section was added along the south sideline.[1][13][14] In this form the stadium seated 33,150.[15]

The inaugural game at the renovated Exhibition Stadium was an exhibition interleague game between the hometown Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League (CFL) and the Chicago Cardinals of the National Football League (NFL) on August 5, 1959. The game was the first time an NFL team played in Toronto.[16][17] It was also the first NFL–CFL exhibition match held since the establishment of the CFL in 1958, and marked the beginning of a three-year, four game exhibition series between the leagues.

When the 58th Grey Cup was played at the stadium in 1970, Calgary Stampeders coach Jim Duncan described the condition of the natural-grass surface as "a disgrace."[18] In January 1972, Metropolitan Toronto Council voted 15–9 to spend $625,000 to install artificial turf. The vote passed despite five councillors changing their vote to oppose the motion, because the cost had increased from a previous estimate of $400,000.[19] Two months later, contracts totalling CA$475,000 were approved to install the AstroTurf, with work to be completed by June, in time for the start of the Toronto Argonauts' 1972 season.[20]

Reconfiguration for baseball

[edit]In 1974, in a bid to acquire a Major League Baseball team, the city voted to reconfigure the stadium to make it compatible for baseball,[21] leading to the arrival of Major League Baseball in Toronto in 1977 in the form of the expansion Toronto Blue Jays after a failed attempt to lure the San Francisco Giants to the city.

Originally planned to cost CA$15 million[21] before growing to CA$17.5 million ($88.4 million in 2023 dollars)[22], the renovations, which were funded by the city and province, added seating opposite to the covered grandstand on the first base side and curving around to the third base side.[1][2][23][24][25] Football capacity was increased from 33,150 before the renovations to 41,890 initially, then finally to 54,741 after work was completed.[21] Although the stadium was expanded to accommodate baseball, the new seats were first used for football and allowed the 64th Grey Cup in November 1976 to be watched by a then-Grey Cup record crowd of 53,467. For baseball, the stadium originally seated 38,522; however, by the Blue Jays' second season this increased to 43,739,[26] although only about 33,000 seats were usually made available (see below).

Even in its new, expanded form, Exhibition Stadium was problematic for hosting both baseball and football. Blue Jays' President Paul Beeston noted Exhibition Stadium "wasn't just the worst stadium in baseball, it was the worst stadium in sports."[27]

Baseball problems

[edit]

Exhibition Stadium was unusual among MLB ballparks in that it was a football-specific venue later renovated for baseball, whereas most U.S. venues hosting baseball and football were either ballparks where football was a secondary consideration or "cookie-cutter" facilities designed from the outset to host both sports. Like most multi-purpose stadiums, the lower boxes were set further back than comparable seats at baseball-only stadiums to accommodate the wider football field.

Moreover, at the time of the renovation a Canadian football field was almost 34% larger than an American football field.[note 1] While in some respects the larger Canadian field arguably made retrofitting for baseball somewhat easier than was the case south of the border with previous examples such as Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum or future examples such as Mile High Stadium, it nevertheless left many of the seats down the right-field line and in right-centre were extremely far from the infield; they actually faced each other rather than the action. Some seats were as far as 820 feet (250 m) from home plate — the greatest such distance of any stadium ever used as a principal home field in the major leagues.[26] The Blue Jays realized early on that these seats were too far from the field to be of any use during the regular season. As such, they were only sold when necessitated by demand during the 1985 and 1987 pennant races. As the original grandstand was used for the outfield seats, these were the cheapest seats but were the only ones which offered some protection from the elements;[28] the Blue Jays were the only MLB team using a stadium with such a configuration.

Football problems

[edit]Because the full length of the third-base line had to be fitted between the north stand (the original grandstand) and the new south stand, they could no longer be parallel to each other. As a compromise between placements suitable for the two stands, the football field was rotated anticlockwise away from the north stand.[29] Thus, the only seats as close to the field as before were those near the eastern end zone, and no seats had as good a view of the whole field as the centre-field seats before the conversion.

Although the Argonauts recorded average attendances of above 40,000 fans per game in the first few seasons following the stadium's expansion, by the mid-1980s average attendance had fallen to fewer than 30,000 fans per game.

Problems with the wind and cold

[edit]Being situated relatively close to Lake Ontario, the stadium was often quite cold at the beginning and end of the baseball season (and the end of the football season). The first Blue Jays game played there on April 7, 1977, was the only major league game ever played with the field covered entirely by snow. The Blue Jays had to borrow Maple Leaf Gardens' Zamboni to clear off the field. Conditions at the stadium led to another odd incident that first year. On September 15, Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver pulled his team off the field because -- in Weaver's opinion -- he felt the bricks holding down the tarp near the bullpens along each baseline were a possible trip hazard for players trying to catch a ball in foul territory. This garnered a win by forfeit for the Jays – the only time in major league baseball history since 1914 that a team deliberately forfeited a game (as opposed to having an umpire call a forfeiture).[30]

An April 30, 1984, game against the Texas Rangers was postponed due to 60 mph (97 km/h) winds. Before the game, Rangers manager Doug Rader named Jim Bibby as his starting pitcher, stating "he's the heaviest man in the world, and thus will be unaffected by the wind." However, Bibby would never make it to the mound. Two Rangers batters complained about dirt swirling in their eyes, and Blue Jays starting pitcher Jim Clancy was blown off balance several times. The umpires stopped the game after only six pitches. After a 30-minute delay, the game was called off.[31]

The stadium also occasionally had problems with fog, once causing a bizarre inside-the-park home run for Kelly Gruber in 1986, when an otherwise routine pop up was lost by the outfielders in the thick fog.[32]

As a popular feeding ground for seagulls

[edit]Due to its position next to the lake, and the food disposed by baseball and football fans, the stadium was a popular feeding ground for seagulls. New York Yankees outfielder Dave Winfield was arrested on August 4, 1983, for killing a seagull with a baseball. Winfield had just finished his warm-up exercises in the 5th inning and threw a ball to the ball boy, striking a seagull in the head. The seagull died, and some claimed that Winfield hit the bird on purpose, which prompted Yankees manager Billy Martin to state "They wouldn't say that if they'd seen the throws he'd been making all year. It's the first time he's hit the cutoff man". The charges were later dropped. Winfield would later play for the Blue Jays, winning a World Series with the club in 1992.

70th Grey Cup and replacement

[edit]Exhibition Stadium's fate was sealed during the 70th Grey Cup in 1982, popularly known as "the Rain Bowl" because it was played in a driving rainstorm that left most of the crowd drenched. Many of the seats were completely exposed to the elements, forcing thousands of fans to watch the game in the concession section. To make matters worse, the washrooms overflowed. In attendance that day was then-Ontario Premier Bill Davis, and the poor conditions were seen by over 7.862 million television viewers in Canada (at the time the largest TV audience ever in Canada).[33] The following day, at a rally at Toronto City Hall, tens of thousands of people who were there to see the Toronto Argonauts began to chant, "We want a dome! We want a dome!" So too did others who began to discuss the possibility of an all-purpose, all-weather stadium.[34]

Seven months later, in June 1983, Premier Davis formally announced that a three-person committee would look into the feasibility of building a domed stadium at Exhibition Place. The committee consisted of Paul Godfrey, Larry Grossman and former Ontario Hydro chairman Hugh Macaulay.[35] That same year, the city also studied a number of potential sites for the new domed stadium, and in April 1984, CN agreed to donate 7 acres (2.8 ha) of land near the CN Tower for the stadium; groundbreaking began in October 1986, and the stadium, which would take on the name SkyDome (now Rogers Centre), opened in June 1989.[36]

Life following the opening of SkyDome and demolition

[edit]Exhibition Stadium mostly stayed inactive over the decade following the opening of SkyDome (being used sometimes as a racetrack or a parking lot), except for the occasional concert or minor sporting event. The World Wrestling Federation (now WWE), needing a new venue after a decision to discontinue events at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1995, held one card at the stadium on August 24, 1996, for a crowd of 21,211. The main event was Shawn Michaels vs. Goldust in a ladder match.[37] A series of CASCAR races were held at the track during the 1990s, with the stadium being reconfigured for such races.

The stadium was demolished in 1999 and the site is now the location of BMO Field and a parking lot. A few chairs from the stadium can be found on the southeast corner just north of the bridge to Ontario Place's main entrance. As is common with stadium demolitions, a number of the remaining seats were sold to fans and collectors. The original locations of all bases and home plate are marked in the parking lot south of BMO Field.

The "Mistake by the Lake"

[edit]Although not widely used while the stadium was in operation (given the well known references to Cleveland's Municipal Stadium), the term "Mistake by the Lake" has been used more recently in reflection by Toronto media to refer to the now-demolished venue.[38]

New stadium

[edit]On October 26, 2005, the City of Toronto approved a CA$69 million proposal to build a 20,000-seat stadium near where the old stadium once was. The governments of Canada and Ontario funded CA$35 (equivalent to $51.39 in 2023) million, with the city paying CA$9.8 million, and Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment paying the rest, including any runoff costs.[citation needed] Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment was awarded a Major League Soccer expansion team, Toronto FC, that debuted on April 28, 2007, at the stadium.[39]

BMO Field was initially built as a soccer-specific stadium with field dimensions that were too small to accommodate a Canadian football field and was operated as such until 2015 when MLSE owners Larry Tanenbaum and Bell Canada agreed to purchase the Toronto Argonauts. As part of the agreement, BMO Field was renovated to allow the Argonauts to move back to the site in time for the 2016 CFL season; the project involved the addition of new seats and a roof as well as lengthening the playing field by using retractable seating.[40] The stadium hosted the 104th Grey Cup, MLS Cup 2016, and the outdoor NHL Centennial Classic game within a 36-day period in late 2016.[41] BMO Field also hosted the MLS Cup in 2010 and 2017, along with the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup.[39] The stadium is planned to host matches at the 2026 FIFA World Cup.[42]

Chevrolet Beach Volleyball Centre

[edit]For the 2015 Pan American Games and Parapan American Games, the old stadium footprint (parking lot) became the Chevrolet Beach Volleyball Centre. The temporary venue had bleachers and a playing area filled with 3,000 metric tonnes of sand.[43] After the Pan American Games, the venue was torn down to allow for setup of rides and restore parking spaces for the 2015 Canadian National Exhibition opening on August 21 of the same year.

Concerts and events

[edit]Many rock concerts were also held at the stadium, both the grandstand and the whole stadium were used for popular rock and pop acts such as Pink Floyd, The Who, U2, David Bowie, Chicago, New Order, Depeche Mode, Iron Maiden, Rush, Van Halen, Guns N' Roses, Liza Minnelli, Kim Mitchell, Bruce Springsteen, Bette Midler, INXS, Bon Jovi, AC/DC, Elton John, Whitney Houston and Janis Joplin, New Kids On The Block.[citation needed]

- On July 18, 1958, Richard Petty made the first of 1,184 starts in NASCAR Grand National Series competition in a race at the grandstand, entitled the 1958 Jim Mideon 500. Today, the roads of the Exhibition Place are used for the INDYCAR Honda Indy Toronto and since 2010 has hosted the NASCAR Pinty's Series.

- The stadium was featured on a Season 4 Route 66 episode titled "A Long Way from St. Louie" which first aired on December 6, 1963. While on a helicopter tour over downtown Toronto, Tod Stiles and Linc Case (Martin Milner and Glenn Corbett, respectively) spot a quintet of girl musicians (two were played by Lynda Day and Jessica Walter), who were stranded in the city, sleeping on the benches in the covered north grandstand.

- 1967 saw the Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo 1967 perform eight shows at the stadium to standing ovations every night. So popular with crowds at the stadium of 30,000 most nights, the 89-year-old never on Sunday taboo had to be waived to permit the Tattoo to put on a Sunday, September 3 performance to accommodate the extraordinary demand for tickets. John Holden, a CNE official stated, "It was breathtaking. You just can't compare it with the like of anything that has come before it." CNE General Manager Bert Powell stated, "We've never had anything like it — fabulous and fantastic. My phone is never quiet. I'm even getting professional critics and entertainers begging for tickets, and that's the ultimate tribute."

- On August 30, 1980, Queen performed a concert from The Game Tour.

- Soccer Bowl '81 was played at Exhibition Stadium.

- In 1982, the 70th Grey Cup game held at the stadium had the largest number of television viewers in Canadian history, with 7,862,000. The record has since been broken.

- The Who Its Hard Tour October 9, 1982

- The Jacksons performed three concerts at the stadium on October 5, 6 and 7, 1984 during their Victory Tour in front of 180,000 in attendance.

- In 1985, the first Game 7 in the history of the ALCS was played at the stadium. The Blue Jays lost to the Kansas City Royals, 6–2.[44]

- On August 28, 1986, the stadium played host to the World Wrestling Federation's "Big Event" card in front of 65,000 fans. The main event was then-World Heavyweight Champion Hulk Hogan against Paul Orndorff.[45]

- Van Halen August 18, 1986, capacity concert sellout the first new tour with Sammy Hagar as lead singer

- Genesis sold out the stadium on September 22, 1986, at 8:00 P.M. to a sold-out crowd of 61,000 people as a part of their North American leg of the Invisible Touch Tour.

- AC/DC played the stadium on September 12, 1986, on their Who Made Who Tour.

- Iron Maiden played the stadium in 1988 and 1992.

- U2 played the stadium on the Joshua Tree Tour on October 3, 1987, and on the Zoo TV Tour on September 5 and 6, 1992.

- Madonna brought her Who's That Girl World Tour to the stadium on July 4, 1987, before a sold out crowd of 50,013 people.

- Pink Floyd performed three concerts on September 21, 22 and 23, 1987 and next year on May 13, 1988, as part of their A Momentary Lapse of Reason Tour. They returned to the stadium for three nights on July 5, 6 and 7, 1994 as part of their The Division Bell Tour.

- Bon Jovi played the stadium as part of their New Jersey Syndicate Tour on June 2, 1989.

- The Rolling Stones performed at the stadium in September 3 and 4, 1989 during their Steel Wheels/Urban Jungle Tour.

- Guns N' Roses played the stadium on back-to-back nights, June 7 and 8, 1991, as part of their Use Your Illusion Tour.

- Guns N' Roses returned to the stadium in just over a year, on September 13, 1992, this time on a double bill with Metallica, performing as part of their joint Guns N' Roses/Metallica Stadium Tour, with Faith No More as the opening act.

- Paul McCartney brought his New World Tour to the stadium on June 6, 1993. It would be his last show in Canada until April 2002.

^ A. Game was suspended with 9:29 remaining in the fourth quarter due to extremely dense fog, and completed the next day.

| Game | Date | Winning team | Score | Losing team | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th | November 24, 1973 | Saint Mary's Huskies | 14–6 | McGill Redmen | 17,000 |

| 10th | November 22, 1974 | Western Ontario Mustangs | 19–15 | Toronto Varsity Blues | 24,777 |

| 11th | November 21, 1975 | Ottawa Gee-Gees | 14–9 | Calgary Dinos | 17,841 |

| 1985 American League Championship Series | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Game | Date | Winning team | Score | Losing team | Time | Attendance |

| 1 | October 8, 1985 | Toronto Blue Jays | 6-1 | Kansas City Royals | 2:24 | 39,115[46] |

| 2 | October 9, 1985 | Toronto Blue Jays | 6-5 | Kansas City Royals | 3:39 | 34,029[47] |

| 6 | October 15, 1985 | Kansas City Royals | 5-3 | Toronto Blue Jays | 3:12 | 37,557[48] |

| 7 | October 16, 1985 | Kansas City Royals | 6-2 | Toronto Blue Jays | 2:49 | 32,084[49] |

| Kansas City won the series, 4–3 | ||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Until the size of the CFL endzones were reduced from 25 yards to 20 in 1986, the Canadian field was 40 yards (37 m) longer and 35 feet (11 m) wider.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Brehl, Robert (May 23, 1989). "The noteworthy and not-so-worthy Ex Stadium has survived fires, storms and seagulls". Toronto Star.

- ^ a b Brehl, Robert (May 23, 1989). "Those were the days? Exhibition Stadium had it all: cold and rain and shivering fans. "Enough's enough", declared two sports nuts, vowing to build a dome". Toronto Star.

- ^ Lott, John, and McGrath, Kaitlyn (May 8, 2020). "Inside the Ex: Tales from the Blue Jays' ugly, quirky, yet lovable first home". The Athletic. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beard, Randy (April 25, 1979). "Blizzard Hope Revenge Snowballs The Rowdies". Evening Independent. p. 1C. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Beard, Randy (May 4, 1984). "Down 3 more teams, but NASL is stronger". Evening Independent. p. 6C. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "1985 CNE Grandstand Performers". Cnearchives.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "'To Cost Over 4 Million,' Asks Grandstand Probe". The Globe and Mail. September 21, 1948.

- ^ "Fireworks Over CNE: Council Would Let Ex Boss Grandstand, Field; Fiery Aldermen Object". The Globe and Mail. November 2, 1948.

- ^ Coleman, Jim (September 29, 1948). "By Jim Coleman". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Tumpane, Frank (December 7, 1949). "Sweet reason". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Spring Rehabilitation: Offer to Improve CNE Sports Field For 1950 Grey Cup". The Globe and Mail. December 7, 1949.

- ^ "Almost Pigeon-Proof; CNE Grandstand Ready". The Globe and Mail. August 2, 1948. p. 5.

- ^ Westall, Stanley (August 5, 1960). "With $450,000 Stake the City couldn't lose, it was said, but it did". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "CNE Stadium Muddle". The Globe and Mail. November 24, 1959.

- ^ Toronto Argonauts 1959 Fact Book, inside front cover.

- ^ Teitel, Jay (1983). The Argo Bounce. Toronto, Ontario: Lester and Orpen Dennys. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-88619-033-9.

- ^ "Argos Smothered By Cardinals And Lose Norm Stoneburgh". Canadian Press. August 6, 1959. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ "History - Grey Cup - 1970". Canadian Football League website. Canadian Football League. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ "Sports to boom at CNE stadium with mod sod". Toronto Star. January 26, 1972. p. 14.

- ^ "Estimate was $625,000: CNE artificial sod to cost $475,000". Toronto Star. March 29, 1972. p. 45.

- ^ a b c Simpson, Jeff (February 27, 1974). "Work could start this fall: Metro votes 23 to 6 to enlarge the CNE Stadium". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ 1688 to 1923: Geloso, Vincent, A Price Index for Canada, 1688 to 1850 (December 6, 2016). Afterwards, Canadian inflation numbers based on Statistics Canada tables 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021) "Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 17, 2021. and table 18-10-0004-13 "Consumer Price Index by product group, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit". Statistics Canada. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ MacCarl, Neil (June 5, 1976). "CNE Stadium: $17.8 million home for baseball". Toronto Star.

- ^ Best, Michael (July 18, 1977). "Blue Jays score in millions for Metro". Toronto Star.

- ^ Kirkland, Bruce (July 2, 1977). "Forum music, CNE noise: Will they ever co-exist?". Toronto Star.

- ^ a b Lowry, Phillip (2005). Green Cathedrals. New York City: Walker & Company. ISBN 0-8027-1562-1.

- ^ Macleod, Robert (September 25, 2015). "Paul Beeston heads for the bench". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Curt (2001). Storied Stadiums. New York City: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1187-6.

- ^ Illustration at: "Exhibition Stadium". Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ "Remembering the game that Earl Weaver forfeited at Exhibition Stadium". January 23, 2013.

- ^ Bradbeer, Janice (March 31, 2016). "Once Upon A City: Mistake by the Lake's troubled place in Toronto history | The Star". The Toronto Star.

- ^ "Tigers in a Fog as Blue Jays romp to win". Montreal Gazette. Canadian Press. June 13, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ Canadian Football League, Canada.

- ^ Paikin, Steve (October 22, 2016). Paikin on Ontario's Premiers 2-Book Bundle: Bill Davis / Paikin and the Premiers. Dundurn. p. 785. ISBN 978-1-4597-3833-1.

- ^ Miller, David (October 7, 1984). Battle Is On for Right to Build Our Domed Stadium. Toronto Star. pg A1, A13.

- ^ "Historicist: The Road to SkyDome". Torontoist. June 13, 2009.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip (June 5, 2019). "WWF Xperience 1996". The Internet Wrestling Database. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ Woolsey, Garth (May 30, 2009). "Toronto's dome turns 20". Toronto Star. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Stejskal, Sam (December 8, 2016). "BMO Field 101: Toronto FC's stadium set to host MLS Cup after facelift". MLSsoccer.com. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Davidson, Neil (April 10, 2015). "Clock ticking on BMO Field deal if Argos want to play there in 2016". The Globe and Mail. The Canadian Press. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Brady, Rachel (December 30, 2016). "BMO Field's hat trick: Three sports, four games, five weeks, one stadium". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Takagi, Andy (February 5, 2024). "Toronto's BMO Field is getting a new name for the 2026 FIFA World Cup". Toronto Star. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ "Chevrolet Beach Volleyball Centre | Toronto 2015 Pan Am / Parapan American Games". Archived from the original on April 27, 2014.

- ^ Woosley, Garth (October 17, 1985). "IT'S OVER!". The Toronto Star. p. BJ1. Retrieved January 29, 2024 – via Proquest.

- ^ Miller, David; Brehl, Robert; Cheney, Paul (August 29, 1986). "Record 65,000, holler for Hulk". The Toronto Star. pp. A1, A12. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "1985 ALCS Game 1 - Kansas City Royals vs. Toronto Blue Jays". Retrosheet. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ "1985 ALCS Game 2 - Kansas City Royals vs. Toronto Blue Jays". Retrosheet. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ "1985 ALCS Game 6 - Kansas City Royals vs. Toronto Blue Jays". Retrosheet. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ "1985 ALCS Game 7 - Kansas City Royals vs. Toronto Blue Jays". Retrosheet. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

External links

[edit]- Virtual Walking tour of Exhibition Place

- Overhead photo of Exhibition Stadium Archived March 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- BallparksOfBaseball.com

- Ballparks.com

- Several photos including CNE racetrack configuration

- Baseball field diagram

- Football configuration

- Video about Exhibition Stadium (YouTube)

- The Governor General's Foot Guards Band with the band of the Royal Regiment of Canada at the Toronto Exhibition Stadium in 1984

- Exhibition Stadium NASCAR's race results at Racing-Reference

- Exhibition Stadium at SABR Bio Project

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by first ballpark

|

Home of the Toronto Blue Jays 1977–1989 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Toronto Argonauts 1959–1988 |

Succeeded by |

- Sports venues completed in 1959

- Sports venues demolished in 1999

- Defunct baseball venues in Canada

- Defunct soccer venues in Canada

- Defunct Canadian football venues

- Canadian Football League venues

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- Defunct sports venues in Toronto

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984) stadiums

- Toronto Argonauts

- Toronto Blue Jays stadiums

- Multi-purpose stadiums in Canada

- NASCAR tracks

- 1959 establishments in Ontario

- 1999 disestablishments in Ontario

- Defunct motorsport venues in Canada

- Defunct sports venues in Canada

- Demolished buildings and structures in Ontario

- Soccer venues in Ontario

- Baseball venues in Ontario

- Canadian football venues in Ontario

- Demolished sports venues

- Toronto Blizzard (1971–1984)

- Serbian White Eagles FC