Bandar Seri Begawan

Bandar Seri Begawan

بندر سري بڬاوان (Jawi) | |

|---|---|

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Mandarin | 斯里巴加湾市 Sīlǐbājiāwānshì (Hanyu Pinyin) |

| Nicknames: The Venice of the East[1] | |

| Coordinates: 4°53′25″N 114°56′32″E / 4.89028°N 114.94222°E | |

| Country | Brunei |

| District | Brunei–Muara |

| Settled | 1906 |

| Administrative centre | 1909 |

| Municipality | 1 January 1921 |

| Renamed Bandar Seri Begawan | 4 October 1970 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Bandar Seri Begawan Municipal Board |

| Area | |

• Total | 100.36 km2 (38.75 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate (2007) | 100,700 |

| • Density | 1,003.39/km2 (2,598.8/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (BNT) |

| Area code | +673 2 |

| Website | bandaran-bsb.gov.bn |

Bandar Seri Begawan[a] (BSB) is the capital and largest city of Brunei. It is officially a municipal area (kawasan bandaran) with an area of 100.36 square kilometres (38.75 sq mi) and an estimated population of 100,700 as of 2007.[3][needs update] It is part of Brunei–Muara District, the smallest yet most populous district which is home to over 70 percent of the country's population.[4] It is the country's largest urban centre and nominally the country's only city. The capital is home to Brunei's seat of government, as well as a commercial and cultural centre. It was formerly known as Brunei Town until it was renamed in 1970 in honour of Omar Ali Saifuddien III, the 28th Sultan of Brunei and the father of Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah.

The history of Bandar Seri Begawan can be traced back to the establishment of a Malay stilt settlement on the waters of the Brunei River which became the predecessor of Kampong Ayer today. It became the capital of the Bruneian Sultanate from the 16th century onwards, as well as in the 19th century when it became a British protectorate. The establishment of a British Residency in the 20th century saw the establishment of modern-day administration on land, as well as the gradual resettlement of the riverine dwellers to the land. During World War II, the capital was occupied by the Japanese forces from 1941 and bombed in 1945 upon liberation by Allied forces. Brunei's independence from the British was declared on 1 January 1984 on a square in the city centre.

Bandar Seri Begawan is home to Istana Nurul Iman, the largest residential palace in the world by the Guinness World Records,[5] and Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque, Brunei's iconic landmark. It is also home to Kampong Ayer, the largest 'water village' in the world and nicknamed Venice of the East.[6] It was once the host city of the 20th Southeast Asian Games in 1999 and 8th APEC Summit in 2000.

Etymology

[edit]Bandar Seri Begawan was named after Omar Ali Saifuddien III, the 28th Sultan of Brunei.[7] Seri Begawan is part of the royal title bestowed on the late sultan upon his abdication in favor of his son, Hassanal Bolkiah, in 1967.[7][8] The city was renamed on 4 October 1970 to commemorate his contribution to the modernisation of the country during his reign in the 20th century.[9][10][11] Prior to this, the city had been known as Brunei Town or Bandar Brunei in Malay (literally "Brunei City").[12][13]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The growth and development of Brunei's historic capital city unfolded in three main stages. The first stage began in the 17th century with the emergence of a water settlement near present-day Kota Batu. In the second stage, the capital shifted to the area around what is now Kampong Ayer—a collection of water villages.[14] Today, Kampong Ayer, originally the ancient capital built over the Brunei River, serves as a suburb of the modern capital on adjacent land,[15] having thrived particularly during Sultan Bolkiah's reign.[16] This city was developed on land during the third phase, particularly after 1906.[14]

Over 300 years of intermittent conflict between the Malay Muslim tribes and Spanish conquistadors, known in Spanish chronicles as the Moro Wars, began in 1578 when Catholic Spaniards attacked Kampong Ayer during the Castilian War.[16] Pirates, many of whom were Muslim sailors from the southern Philippines and Borneo, including destitute princes from the royal families of Sulu and Brunei, took advantage of the void left by Kampong Ayer's loss in authority throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Along with other important sites like Endau and Jolo, the capital became a major hub for piracy and the trade in stolen goods and slaves as the sultan attempted to regulate or tax these pirate towns.[17]

Kampong Ayer was still humble and less affluent by the middle of the 19th century, and its look had not altered much since Antonio Pigafetta's time. It was dubbed a "Venice of hovels" by Rajah James Brooke in 1841. Houses were constructed on mudflats, encircled by mud at low tide and water at high tide, and a floating market was crowded with people peddling things from canoes. Despite its unattractive appearance, the town was renowned for its packed buildings and the spacious but uncomfortable palace, where Brooke was made to feel quite welcome by the sultan and his court despite the gloomy and basic lodgings.[18]

Known as the "Venice of Borneo," Kampong Ayer is distinguished by its position on a wide river that empties into a sizeable lake and by the fact that its homes are perched on piles that are around 10 feet (3.0 m) above the tide. The formerly thriving town has lost both size and significance, as seen by its dilapidated buildings and shortage of defences. Once enclosed by a sturdy brick wall and furnished with opulent furnishings, the sultan's palace looks like a cheap shed. The town's filthy state is exacerbated by offensive smells coming from uncovered mud, where waste builds up. In sharp contrast to the town's historical splendour, the majority of the population is made up of slaves and the Sultan's and nobility's dependents.[19]

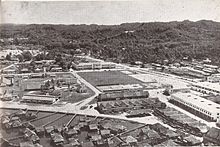

Colonial era

[edit]Brunei Town's development unfolded in three major phases, with the third beginning in 1906 under Malcolm McArthur's guidance, focusing on transitioning the settlement to land.[14] His vision aimed to address the sanitation issues that were most severe in Kampong Ayer, a water village with 8,000–10,000 residents when the Residential system was introduced. McArthur prioritised constructing a land-based colony,[20] starting with his own residence, Bubungan Dua Belas, even though the sultan's palace remained in Kampong Ayer.[21] By 1910, Chinese immigrants had opened shops, further establishing the colony on land.[14]

In 1911, the water village, largely populated by Malay Muslim and a small Kedayan community in nearby areas, was home to many houses built over water.[22] The capital endured severe hardship after losing Limbang, which had provided essential resources to river villagers; this loss also undermined Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin's prestige and authority amid growing economic challenges.[23] In 1920, the area was officially designated as Brunei’s capital and municipal territory.[14] Along the western riverbanks, government buildings and a mosque were constructed in the same year.[8] Later on 1 January 1921, the Brunei Town Sanitary Board (BTSB) was established to oversee its development.[14] In 1922, Sultan Muhammad Jamalul Alam II's decision to relocate his palace from Kampung Sultan Lama to the interior of Brunei Town[b] renewed interest in Resident McArthur's proposal for relocating the Kampong Ayer community. His involvement inspired Kampong Ayer residents to consider mainland resettlement, and relocation efforts in the 1920s began expanding beyond the city centre to areas like Tungkadeh and Kumbang Pasang, marking a significant shift in Brunei’s urban development.[25]

After the Japanese launched an assault starting in Kuala Belait, Brunei Town was overrun by them on 22 December 1941. To British officers they had seized, the Japanese declared their intention to free Asia from colonial rule.[26] Due to an Allied embargo that hampered the local economy, Brunei Town experienced extreme economic duress during the Japanese occupation. On 22 December 1941, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin, who was based in Kampong Sumbiling, surrendered to General Tawaguchi. By encouraging agriculture and requiring farmers to turn over a percentage of their harvests, Japan sought to integrate Brunei's culture and economy with its own, appointing Ibrahim Mohammad Jahfar as head of administration under Governor Takamura.[27] The Japanese instituted stringent cultural initiatives, such as teaching Japanese language and values and establishing youth groups like the Brunei Malay Organisation, in an effort to exploit the oil riches. The town was brutally bombarded by Allied forces beginning in November 1944 and subjected to extreme brutality by the Japanese military police, the Kempeitai.[28]

After three days of warfare, American and Australian forces captured Brunei on 10 June 1945, but Brunei Town suffered significant damage. Brunei Malays had a stronger sense of national identity at this time, and local partners went on to play important roles in the burgeoning nationalist movement.[28] The town's wartime population of 16,000 was reduced to a small number of people who remained when the war came to a close due to Allied bombs and food shortages. Residents were forced to observe from neighboring hills or take cover in the bush after the bombers destroyed almost all of the town's homes and businesses. Bruneians started reconstructing their homes out of the debris left by the bombs after the Japanese withdrew into the forest in June 1945.[29]

The town became a focal point for important institutional and religious transformation following the war. To further Islamic matters, a board of 19 notable individuals and not all of them were religious experts, was formed in 1948. In order to increase the sultan's legitimacy in the face of British scrutiny, this reform sought to standardise religious courts, codify Islamic law, and enhance the management of Islamic services under his direct control. Despite having little contact with Brunei's western regions, new groups like the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation contributed to the region's religious life in the 1950s, which witnessed a considerable increase in religious activity in the town. Despite the oil industry's fast growth in urban areas like Seria and Kuala Belait, no clear regional religious identity was able to emerge because of the close institutional ties between Brunei Town's religious establishment and the surrounding districts.[30]

In the post-war period, particularly throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Brunei focused on social and religious growth as well as urban reconstruction. Years of occupation during the Pacific War had left the city’s infrastructure severely damaged, necessitating quick solutions like the rapid reconstruction of Brunei Town's stores and the temporary thatched-roof rebuild of Masjid Kajang.[31] In 1953, the town saw significant investment through a five-year National Development Plan funded with M$100 million, primarily for infrastructure, following Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III's successful negotiation with the British for increased corporate taxes and expanded war reparations.[32] In 1953, a major development plan was introduced, dedicating $100 million to the city's growth—a significant investment for a community of just 54,000.[31] That same year on 1 August,[33] the BTSB was renamed the Brunei Town Municipal Board (BTMB) and administered by the British Resident until 1959. From then on, the Brunei–Muara District Officer took on dual roles as head and chairman of the BTMB.[14]

Brunei's population tripled to 83,877 by 1960 as a result of immigration brought on by oilfield finds in Belait.[22] The capital was now competing economically with the burgeoning cities of Seria and Kuala Belait. Although the majority did not hold Bruneian citizenship, the Chinese community, who were extensively involved in local commerce, increased to a quarter of the population by 1960.[34] The Brunei revolt began on 8 December 1962, when the North Kalimantan National Army quickly captured Brunei Town, the oilfields at Seria, and portions of Sarawak and North Borneo. In response, British forces, including Gurkhas and Royal Marines, regained control of most key centres by 11 December, resulting in the capture or surrender of around 2,700.[35]

Independence era

[edit]Together with the expansion of the oil and gas industry, commercialisation began to transform Brunei's capital and a large number of public buildings were constructed, along with the development of a central business district in the 1970s and 1980s.[8][12] Brunei Town was formally renamed Bandar Seri Begawan on 4 October 1970, in honour of the retired Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III, with the renaming ceremony held at the capital.[36] On 1 January 1984, at midnight, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah declared Brunei's independence at the Taman Haji Sir Muda Omar 'Ali Saifuddien.[37] The Ministry of Home Affairs has been in charge of the Bandar Seri Begawan Municipal Board since the country's independence in 1984. The new town has grown along Jalan Berakas and Jalan Muara in the north and Jalan Tutong and Jalan Gadong in the west.[14] A 1998 Asia Week study ranked Bandar Seri Begawan among Asia's top capital cities for 1999 and 2000, highlighting its cleanliness and security as key factors in its recognition.[38]

On 1 August 2007, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah gave consent for the expansion of the city from 12.87 km2 (4.97 sq mi) to 100.36 km2 (38.75 sq mi).[39]

Government

[edit]The city is administered by the Bandar Seri Begawan Municipal Board within Bandar Seri Begawan Municipal Department, a government department within the Ministry of Home Affairs. The Municipal Board was established in 1921, originally as a Sanitary Board (Lembaga Kebersihan) which was, and is still, responsible for maintaining the cleanliness to the then Brunei Town.[40] It achieved the status of bandaran (municipality) in 1935 with the conversion of the Sanitary Board into the current Municipal Board (Lembaga Bandaran).[40]

The city is located in Brunei–Muara District, the smallest yet the most populous district in the country,[41] and as of 1 August 2007, the municipal area has been expanded from 12.87 square kilometres (4.97 sq mi) to 100.36 square kilometres (38.75 sq mi). The Bandar Seri Begawan area encompasses several mukims and villages within the district, including Mukim Berakas 'A', Mukim Berakas 'B', Mukim Burong Pingai Ayer, Mukim Gadong 'A', Mukim Gadong 'B', Mukim Kianggeh, Mukim Kilanas, Mukim Kota Batu, Mukim Peramu, Mukim Saba, Mukim Sungai Kebun, Mukim Sungai Kedayan, and Mukim Tamoi.[42][43]

Geography

[edit]The Brunei–Muara District, encompassing 563 square kilometres (217 sq mi), is the smallest of Brunei’s western districts and is home to Bandar Seri Begawan. The area contrasts sharply with the mountainous Temburong District to the east, featuring low hills, marshy coastal plains, and narrow alluvial valleys along key rivers.[44] Between Tutong and the capital, hills approach the coast, while the coastal plains around Bandar Seri Begawan remain low and marshy, particularly to the south. Brunei's territory is divided by the Limbang region of Sarawak, which historically served as the capital's natural hinterland until its cession to Sarawak in 1890.[45] The city is easily accessible from Bukit Kota, a 133-meter (436 ft) hill near the eastern boundary of Brunei's western area,[46] while TV broadcasts were transmitted from nearby Subok Hill.[47]

The Brunei River, which flows into Brunei Bay, is one of several waterways converging near Bandar Seri Begawan. Key subcatchments—Kedayan River, Sungai Damuan, and Sungai Imang—enter the low-lying, swampy Brunei River basin at various points, with Kedayan River joining close to the city. The area is bordered by ridges and estuarine plains, experiencing significant urban development. The neighboring Tutong and Belait rivers add to the region’s complex estuarine and floodplain systems.[48] A strip of thick coal seams runs along the coastline between Bandar Seri Begawan and Muara.[49]

Climate

[edit]Brunei has an equatorial, tropical rainforest climate more subject to the Intertropical Convergence Zone than to the trade winds and rare cyclones. The climate is hot and wet.[50] The city sees heavy precipitation throughout the year, with the northeast monsoon blowing from December to March and the southeast monsoon from around June to October.[51] The wettest day on record is 9 July 2020, when 662.0 millimetres (26.06 in) of rainfall was reported at the airport.

| Climate data for Bandar Seri Begawan (Brunei Airport) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1972–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.5 (95.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.2 (97.2) |

36.2 (97.2) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.9 (98.4) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.9 (94.8) |

36.2 (97.2) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 33.0 (91.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.7 (94.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.5 (92.3) |

34.2 (93.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.5 (81.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 320.6 (12.62) |

162.9 (6.41) |

143.4 (5.65) |

241.8 (9.52) |

260.3 (10.25) |

237.7 (9.36) |

241.8 (9.52) |

231.5 (9.11) |

235.1 (9.26) |

313.6 (12.35) |

322.9 (12.71) |

358.9 (14.13) |

3,070.5 (120.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 18.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 16.0 | 18.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 21.0 | 22.0 | 22.0 | 211 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 85 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 84 | 84 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 85 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 214.3 | 209.1 | 230.0 | 239.2 | 239.1 | 216.5 | 223.8 | 225.4 | 197.2 | 211.1 | 216.6 | 204.2 | 2,626.5 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation,[52] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes, 1971–2012 and humidity, 1972–1990)[53] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]The Bruneian Census 2011 Report estimated the population of Bandar Seri Begawan to be approximately 20,000, while the metropolitan area has around 279,924.[54][55] The majority of Bruneians are Malays, with Chinese being the most significant minority group.[55] Aboriginal groups such as the Bisaya, Belait, Dusun, Kedayan, Lun Bawang, Murut, and Tutong also exist. They are classified as part of the Malay ethnic groups and have been given the Bumiputera privileges.[54] Large numbers of foreign workers are also found within Brunei and the capital city, with the majority being from Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia (mostly Betawi, Batak, Ambon, Minahasa, Aceh, Malay and Minangkabau), and the Indian subcontinent.[56][57]

Main sights and tourism

[edit]

Numerous important historical and religious sites may be found in Bandar Seri Begawan. The Ash-Shaliheen Mosque, Jame' Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque, and Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque are notable mosques. Another noteworthy house of worship is the Pro-Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption. The tombs of Bolkiah and Sharif Ali in Kota Batu are key historical attractions, symbolising Brunei's rich legacy. The Lapau, traditionally used for royal ceremonies, and the Old Lapau, now a gallery in the Brunei History Centre, add to the city's cultural significance. The city also hosts several museums. The Brunei Museum, situated in the Kota Batu Archaeological Park, is the country’s largest archaeological site. Other notable museums include the Brunei Darussalam Maritime Museum, Brunei Energy Hub, Kampong Ayer Cultural and Tourism Gallery, Malay Technology Museum, Royal Regalia Museum, and Bubungan Dua Belas.

Istana Darussalam[58] and Istana Darul Hana are former royal residences of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III, while the Istana Nurul Iman palace currently serves as the residence of Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah.[59] The Secretariat Building, the oldest government structure, holds the seat of government known as "State Secretary."[60] The Raja Ayang Mausoleum, dating back to the 15th century, is believed to honor a royal who was punished for incest, and it has since become a cultural site where visitors often seek blessings, despite some damage caused by offerings. Royal Mausoleum is the main burial ground for several sultans and royal family members of Brunei, adding to the country's historical significance.

The city's suburb incorporates nearby Kampong Ayer, in which houses were built on stilts. It stretches about 8 km (5.0 mi) along the Brunei River. Founded 1,000 years ago,[61] the village is considered the largest stilt settlement in the world, with approximately 30,000 residents and 2,000 houses.[62] The term "Venice of the East" was coined by Pigafetta in honour of the water village that he encountered at Kota Batu. Pigafetta was on Ferdinand Magellan's last voyages when he visited Brunei in 1521.[63]

Several parks and trails in the city serve as landmarks of historical and cultural significance. Taman Haji Sir Muda Omar 'Ali Saifuddien, for example, was where Brunei's declaration of independence was read on 1 January 1984.[64] Taman Mahkota Jubli Emas, inaugurated on 22 October 2017, commemorates the Golden Jubilee of Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah's rule,[65] while the Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Silver Jubilee Park, opened in 2004, celebrates the Silver Jubilee of his reign. Tasek Lama Recreational Park is one of the oldest recognised parks in the country.[66] Additionally, Pusat Belia, Brunei's youth centre, was established on 20 December 1969 after being commissioned by then-Crown Prince Hassanal Bolkiah in 1967.[67][68][69] The centre, costing B$2 million,[70] includes extensive facilities such as a hall for 1,000 people, a gymnastics hall, an Olympic-sized pool, and a gender-separated hostel,[70] and it celebrated its golden jubilee in 2020.[69]

Transportation

[edit]

Land

[edit]The capital is accessible by bus from Bandar Seri Begawan to the western regions of the country via road. Connectivity to the exclave of Temburong is provided by the Sultan Haji Omar Ali Saifuddien Bridge, which opened in 2020—before its construction, travellers had to pass through Sarawak, Malaysia, via the town of Limbang. Additionally, Edinburgh Bridge links the city centre to the rest of the capital by spanning the Kedayan River.[71]

The main bus station in the capital is located in Jalan Cator underneath a multi-story car park. There are six bus routes servicing Bandar Seri Begawan area; the Central Line, Circle Line, Eastern Line, Southern Line, Western Line and Northern Line. Buses operate from 6.30 am until 6.00 pm except for bus No. 1 and 20 for which services extend into the night. All bus routes begin and terminate their journey at the main bus terminal. Buses heading to other towns in Brunei such as Tutong, Seria and Kuala Belait also depart from the main bus terminal and taxicab.

Air

[edit]Brunei International Airport serves the whole country. It is located 11 km (6.8 mi) from the town centre and can be reached in 10 minutes via the Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah Highway. Royal Brunei Airlines, the national airline, has its head office in the RBA Plaza in the city.[72][73]

Water

[edit]Ships up to 280 feet (85 m) long may dock in the former port of Dermaga Diraja Bandar Seri Begawan, which is located 17 miles upstream from the mouth of the Brunei River. A 124-foot passenger pier, a 730-foot reinforced concrete wharf, and an electrically powered ramp are among the port's amenities.[74] Ships may purchase purified fresh water in the capital for $2.00 per 1,000 gallons. The Marine Department keeps track of use and bills the ship's agent. The Bandar Seri Begawan Municipal Board is credited with the money received from these water sales.[75] Between the city and Victoria Harbour, a passenger boat that also transports mail runs every day (except for Sundays). On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays, an outboard motorboat service also carries mail and people between Bandar Seri Begawan to Bangar in Temburong District.[76]

A water taxi service known as 'penambang' is used for transportation between downtown Bandar Seri Begawan and Kampong Ayer. Water taxis are the most common means of negotiating the waterways of Kampong Ayer. They can be hailed from the numerous "docking parts" along the banks of the Brunei River. Fares are negotiable. Regular water taxi and boat services depart for Temburong between 7:45 am and 4 pm daily, and also serve the Malaysian towns of Limbang, Lawas, Sundar and Labuan. A speedboat is used for passengers travelling to Penambang from Bangar and Limbang.

Economy

[edit]The economy of Bandar Seri Begawan includes the production of furniture,[77] textiles, handicrafts, and timber.[78][79] For shopping, the Gadong commercial area is popular, offering a range of shops, restaurants, and cafes. The traditional Kianggeh Market, believed to be Brunei’s oldest market, mainly sells local cuisine, seafood, and fruit.[80] Gadong Night Market is known for its diverse food offerings, from local specialties like roti john, ambuyat, and satay to exotic fruits such as durian and jackfruit.[81]

Education

[edit]Bandar Seri Begawan is home to several notable schools across various educational levels. Primary and secondary institutions include the historic Raja Isteri Girls High School, established in 1957 as the country's first all-girls secondary school,[82][83] along with private schools such as Jerudong International School and International School Brunei. The city also has government sixth form centers: Duli Pengiran Muda Al-Muhtadee Billah College for general studies and Hassanal Bolkiah Boys' Arabic Secondary School for students from Arabic secondary religious schools.

In higher education, Bandar Seri Begawan hosts two national universities: Sultan Sharif Ali Islamic University, focused on Islamic studies,[84] and Seri Begawan Religious Teachers University College, which specialises in training teachers for religious education. Technical and vocational education is available at two campuses of the Institute of Brunei Technical Education[85] and the Brunei Polytechnic. Additionally, two private colleges, Cosmopolitan College of Commerce and Technology and Laksamana College of Business, offer bachelor programs.[86][87]

International relations

[edit]Several countries have set up their embassies, commissions or consulates in Bandar Seri Begawan, including Australia,[88] Bangladesh,[89] Belgium, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burma (Myanmar),[90] Cambodia, Canada,[91] Chile, China,[92] Finland,[93] France,[94] Germany,[95] India,[96] Indonesia,[97] Japan,[98] Laos, Malaysia,[99] Netherlands, New Zealand, North Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia,[100] Singapore,[101] South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand,[102] United Kingdom,[103] United States[104] and Vietnam.[105][106]

Sister cities

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Water taxis on the Brunei River

-

Royal Regalia Museum

-

Secretariat Building

-

Taman Mahkota Jubli Emas

-

Istana Nurul Iman

-

Gadong Night Market

-

Duli Pengiran Muda Mahkota Pengiran Muda Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah Mosque

-

Department of Syariah Affairs building

-

Brunei History Centre

-

Time Piece Monument

-

Gadong commercial area

-

Tomb of Sultan Bolkiah

Notes

[edit]- ^ BAHN-dahr SUH-ree BUH-gah-wahn;[2] Jawi: بندر سري بڬاوان; Malay: [ˌbandar səˌri bəˈɡawan] ⓘ

- ^ Istana Majlis, the new land-based palace of Jamalul Alam, was finished in 1921.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Venice of the East". People.cn. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Saul Bernard (2008). The Columbia Gazetteer of the World: A to G. Columbia University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-231-14554-1.

- ^ "Jabatan Bandaran Bandar Seri Begawan, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri – Maklumat Bandaran". municipal-bsb.gov.bn (in Malay). Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Built environment: Public works are providing a stream of contracts, while reforms and economic diversification pave the way for further growth | Brunei Darussalam 2013 | Oxford Business Group". oxfordbusinessgroup.com. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Largest residential palace | Guinness World Records". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Wong, Maggie Hiufu; Tham, Dan (24 January 2018). "Brunei's Kampong Ayer: Largest settlement on stilts | CNN Travel". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b The Report: Brunei Darussalam 2009. Oxford Business Group. 2009. p. 215. ISBN 9781907065095.

- ^ a b c World and Its Peoples 2007, p. 1206.

- ^ Hayat, Hakim (28 September 2017). "Religious ceremony marks Bandar Brunei renaming". Borneo Bulletin Online. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "PERASMIAN BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN" (PDF). Pelita Brunei (in Malay). No. 40. 7 October 1970. pp. 1, 8. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Department of Government Printing, Prime Minister’s Office, Brunei Darussalam (2013). "Brunei Darussalam In Brief" (PDF). www.information.gov.bn2. p. 45. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ring, Watson & Schellinger 2012, p. 161.

- ^ "Bandar Seri Begawan's Historical Development". brudirect.com. 27 August 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sidhu 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Brown 1984, p. 203.

- ^ a b Wright 1977, p. 13.

- ^ Wright 1977, p. 17–18.

- ^ Wright 1977, p. 19–20.

- ^ Wright 1977, p. 20–22.

- ^ Universiti Brunei Darussalam. "Kampong Ayer Houses". dscapplications.com. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Universiti Brunei Darussalam. "Bubungan 12". dscapplications.com. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b Horton 1986, p. 354.

- ^ Horton 1986, p. 356.

- ^ Pg. Haji Ibrahim 1996, p. 91.

- ^ Asbol 2014, p. 63–64.

- ^ Marles, Jukim & Dhont 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Marles, Jukim & Dhont 2016, p. 8–9.

- ^ a b Marles, Jukim & Dhont 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Marles, Jukim & Dhont 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Mansurnoor 1996, p. 50.

- ^ a b Mansurnoor 1996, p. 49.

- ^ Marie-Sybille de Vienne 2015, p. 105–108.

- ^ Brunei '78 – 81. Bandar Seri Begawan: Information Section, Department of State Secretariat. 1978. p. 37.

- ^ Horton 1986, p. 355.

- ^ Stockwell 2004, p. 798.

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office 1971, p. 363.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam National Day". aipasecretariat.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Dk. Hajah Fatimah Pg. Haji Md. Noor (4 October 2006). "36 tahun penukaran Bandar Brunei menjadi Bandar Seri Begawan hari ini" (PDF). www.pelitabrunei.gov.bn (in Malay). Pelita Brunei. p. 5. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ Shirleen Cambridge (2014). Ultimate Handbook Guide to Bandar Seri Begawan : (Brunei) Travel Guide. MicJames. p. 8. GGKEY:16PGAE1LKCQ.

- ^ a b "Mengenai Bandaran". Jabatan Bandaran Bandar Seri Begawan (in Malay). Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Gwillim Law (30 October 2013). "Districts of Brunei Darussalam". Statoids. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Za'im Zaini; Sonia K (23 July 2007). "Brunei capital to become nearly ten times bigger". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, Embassy of the People's Republic of China in Bandar Seri Begawan. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ "BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN MUNICIPAL BOARD (BOUNDARIES OF MUNICIPAL BOARD AREA) DECLARATION, 2008" (PDF). agc.gov.bn. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Chua, Chou & Sadorra 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Saunders 2013, p. xvi.

- ^ The Brunei Museum Journal. Brunei Museum. 1985. p. 135.

- ^ Gunaratne 2000, p. 229.

- ^ Chua, Chou & Sadorra 1987, p. 10.

- ^ Chua, Chou & Sadorra 1987, p. 65.

- ^ "Brunei", Britannica Student Encyclopedia, 2014, p. 1, ISBN 978-1-62513-172-0

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1999). Irrigation in Asia in Figures. Food & Agriculture Org. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-92-5-104259-5.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020 — Brunei". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Bandar Seri Begawan (Int. Flugh.) / Brunei" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Brunei Darussalam Statistical Yearbook (Brunei Darussalam – An Introduction)" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Brunei. Department of Economic Planning and Development, Prime Minister's Office. 2011. pp. 28/2 and 39/9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Census Report (Demographic Characteristics)" (PDF). Department of Economic Planning and Development. 2011. pp. 4/10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Foreign Workers Information". Brunei Resources. 2005. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "Business Guide – Employment and Immigration". Brunei Economic Development Board. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Pengiran Hajah Mahani binti Pengiran Haji Ahmad (13 May 2013). MELESTARIKAN SEJARAH MELALUI PENAMAAN JALAN (PDF). Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) Asia, South-East Division. jupem.gov.my (in Malay). The Empire Hotel & Country Club, Jerudong. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Mengimbas kembali sejarah lama Makam di Luba". Media Permata. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "The Secretariat Building" (PDF). Brunei Tourism.

- ^ Yunos, Rozan (25 April 2011). "Tracing the history of today's Kampong Ayer". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Piri, Sally (22 October 2011). "Kampong Ayer in Brunei and Borneo". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Kampung Ayer". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Brunei History Centre (10 November 2018). "Tahukah Awda - Ruj. Tahukah Awda?". Pelita Brunei (in Malay). Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ "Sungai Kedayan Eco-Corridor: A piece of the BSB Masterplan comes to life - The Scoop". The Scoop. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Explore Brunei: A Visitor's Guide. Publications Unit, Royal Brunei Airlines. 2000. p. 25.

- ^ "AMANAT Y.T.M. DULI PENGIRAN MUDA MAHKOTA KAPADA BELIA2 TANAH AYER" (PDF). Pelita Brunei (in Malay). No. 12 #36. Jabatan Penyiaran dan Penerangan Kerajaan Brunei. 6 September 1967. p. 4. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Ruj. Tahukah Awda? 030318". Pelita Brunei (in Malay). 3 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Festival Sempena Jubli Emas Penubuhan Pusat Belia". Brudirect.com (in Malay). 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Jabatan Kebajikan bantu Persatuan2 Belia Pusat Belia dalam kerja2 pembenaan" (PDF). Pelita Brunei (in Malay). No. 12 #43. Jabatan Penyiaran dan Penerangan Kerajaan Brunei. 25 October 1967. p. 3. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Haji Adanan Haji Abd. Latiff (2012). Kenali Negara Kitani: Tempat-Tempat Eksotik (in Malay). Bandar Seri Begawan: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-99917-0-855-3.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine." Royal Brunei Airlines. Retrieved on 10 November 2010.

- ^ "World Wide Offices Brunei[permanent dead link]." Royal Brunei Airlines. Retrieved on 10 November 2010. "Bandar Seri Begawan Details: RBA Address: Royal Brunei Airlines. RBA Plaza, Jalan Sultan, Bandar Seri Begawan BS 8811, Brunei Darussalam."

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office 1972, p. 338.

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office 1972, p. 342.

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office 1972, p. 343.

- ^ "Furniture Manufacturers in Bandar Seri Begawan, BN". Yellow Pages. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "Timber Retail in Bandar Seri Begawan, BN". Yellow Pages. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "The 4th China-ASEAN Expo Review". China-ASEAN EXPO Secretariat. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Ak. Jefferi Pg. Durahman (26 August 2017). "Tamu Kianggeh kekal sebagai 'tamu' warisan" (PDF). Pelita Brunei (in Malay). No. 102. Jabatan Penerangan. p. 17. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ "Gadong Night Market". Southeast Asia Travel. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Lilly Suzana Shamsu (December 2018). "HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ON MUSLIM WOMEN'S EDUCATION EMPOWERMENT THROUGH WASATIYYAH CONCEPT IN BRUNEI DARUSSALAM" (PDF). Jurnal Pendidikan Islam. 4 (2). Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Hajah Siti Zuraihah Haji Awang Sulaiman (24 January 2015). "Tinjau perkembangan sekolah menengah dan rendah". Pelita Brunei (in Malay). No. 11 (published 26 January 2015). Information Department. p. 4. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "About Us – Sultan Sharif Ali Islamic University (UNISSA)". unissa.edu.bn. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ IBTE. "IBTE : Institute of Brunei Technical Education – Inspiring Bruneians Towards Excellence". ibte.edu.bn. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "The College". kolejigs.edu.bn. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Home | Laksamana College of Business". Home | Laksamana College of Business. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Australian High Commission Bandar Seri Begawan". Australian High Commission. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Bangladesh High Commission Brunei Darussalam". Bangladesh High Commission. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Bandar Seri Begawan". Myanmar Embassy. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "High Commission of Canada in Brunei Darussalam". Canada International. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of the People's Republic of China in Negara Brunei Darussalam". China Embassy. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Contact information: Finland´s Honorary Consulate, Bandar Seri Begawan (Brunei Darussalam)". Ministry for Foreign Affairs (Finland). Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of France in Brunei Darussalam". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development (France). Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "German Embassy Bandar Seri Begawan". German Embassy. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "The High Commission of India Brunei Darussalam". India Embassy. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia in Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Indonesia). Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of Japan in Brunei Darussalam". Japan Embassy. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Official Website of the High Commission of Malaysia, Bandar Seri Begawan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Malaysia). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of Saudi Arabia – Bandar Seri Begawan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Saudi Arabia). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "High Commission of the Republic of Singapore Bandar Seri Begawan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Singapore). Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Royal Thai Embassy, Bandar Seri Begawan Brunei Darussalam". Thailand Embassy. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "British High Commission Bandar Seri Begawan". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of the United States in Bandar Seri Begawan". US Embassy. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Embassy of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in Brunei Darussalam". Vietnam Embassy. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Foreign Embassies and Consulates in Brunei (36 Foreign Embassies and Consulates in Brunei)". GoAbroad.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Daljit Singh; Pushpa Thambipillai (2012). Southeast Asian Affairs 2012. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 98. ISBN 978-981-4380-23-2.

- ^ "Sister Cities: Bandar Seri Begawan". Nanjing Foreign Affairs Office. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- Marles, Janet E.; Jukim, Maslin; Dhont, Frank (2016). "Memories of World War II: Oral History of Brunei Darussalam (Dec. 1941-June 1942)". Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam (25). Gadong: 1–31.

- Marie-Sybille de Vienne (2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-818-8.

- Asbol, Awang (2014). Hassan, Abdullah (ed.). Persejarahan Brunei: unsur dan faktor persejarahan Brunei (in Malay) (1st ed.). Selangor: PTS Akademik. ISBN 978-967-0444-30-7.

- Saunders, Graham (2013). A History of Brunei. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-87394-2.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 9781136639791.

- Sidhu, Jatswan S. (2009). Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7078-9.

- World and Its Peoples (2007). World and its peoples: Eastern and southern Asia. New York: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3. OL 18734696M.

- Stockwell, A. J. (2004). "Britain and Brunei, 1945-1963: Imperial Retreat and Royal Ascendancy". Modern Asian Studies. 38 (4): 785–819. doi:10.1017/S0026749X04001271. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 3876670.

- Gunaratne, Shelton A. (2000). Handbook of the Media in Asia. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-9427-5.

- Mansurnoor, Iik Arifin (1996). "Socio-Religious Changes in Brunei After the Pacific War". Islamic Studies. 35 (1): 45–70. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20836927.

- Chua, Thia-Eng; Chou, L. M.; Sadorra, Marie Sol M. (1987). The Coastal Environmental Profile of Brunei Darussalam: Resource Assessment and Management Issues. WorldFish. ISBN 978-971-10-2237-2.

- Horton, A. V. M. (1986). "British Administration in Brunei 1906-1959". Modern Asian Studies. 20 (2): 353–374. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00000871. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 312580.

- Brown, D. E. (1984). "Brunei on the Morrow of Independence". Asian Survey. 24 (2): 201–208. doi:10.2307/2644439. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2644439.

- Wright, Leigh (1977). "Brunei: An Historical Relic". Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 17: 12–29. ISSN 0085-5774. JSTOR 23889576.

- Great Britain Colonial Office (1972). State of Brunei Annual Report 1970. Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Great Britain Colonial Office (1971). State of Brunei Annual Report 1971. Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Pg. Haji Ibrahim, Pg. Haji Ismail (1996). Haji Ibrahim, Haji Abdul Latif (ed.). "Seni Bina Rumah Melayu Brunei Satu Tinjauan Ringkas" (PDF). Kampong Ayer: Warisan, Cabaran Dan Masa Depan (in Malay). Bandar Seri Begawan: Academy of Brunei Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam: 75–108.