British Pacific Fleet

| British Pacific Fleet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1944–1945 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Branch | Royal Navy; also Royal Australian Navy; Royal Canadian Navy; Royal New Zealand Navy |

| Engagements | Battle of Okinawa |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Bruce Fraser |

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation which saw action against Japan during World War II. The fleet was composed heavily of British Commonwealth naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944. Its main base was at Sydney, Australia, with a forward base at Manus Island.

Background

The British Pacific Fleet was, and remains, the most powerful conventional fleet assembled by the Royal Navy. By VJ Day it had four battleships, eighteen aircraft carriers, eleven cruisers and many smaller warships and support vessels. Despite this, it was dwarfed by the forces that the United States had in action against Japan.

Following their retreat to the western side of the Indian Ocean in 1942, British naval forces did not return to the South West Pacific theatre until 17 May 1944, when an Anglo-American carrier task force implemented Operation Transom, a joint raid on Surabaya, Java.

The U.S. was liberating British territories in the Pacific and extending its influence. It was therefore seen as a political and military imperative to restore a British presence in the region and to deploy British forces against Japan. The British government were determined that British territories, such as Hong Kong, should be recaptured by British forces.

The British establishment was not unanimous on the commitment of the BPF. Churchill, in particular, argued against it, not wishing to be a visibly junior partner in what had been exclusively the United States' battle. (The Australian and New Zealand forces there had been absorbed into US forces.) He also considered that a British presence would be unwelcome and should be concentrated on Burma and Malaya. Naval planners, supported by the Chiefs of Staff, believed that such a commitment would strengthen British influence and the British Chiefs of Staff considered mass resignation, so strongly held were their opinions.[1] Some U.S. planners had also considered, in 1944, that a strong British presence against Japan was essential to an early end to the war and American home opinion would also be badly affected if Britain did not put itself in the line.

The Admiralty had proposed a British role in the Pacific in early 1944 but the initial USN response had been discouraging. Admiral Ernest King, Commander-in-Chief United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, an alleged Anglophobe,[2] was reluctant to concede any such role and raised a number of objections, including the requirement that the BPF should be self-sufficient. These were eventually overcome or discounted and at a meeting, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt "intervened to say that the British Fleet was no sooner offered than accepted. In this, though the fact was not mentioned, he overruled Admiral King's opinion".[3]

The Australian Government had sought U.S. military assistance in 1942, when it was faced with the possibility of Japanese invasion. While Australia had made a significant contribution to the Pacific War, it had never been an equal partner with its U.S. counterparts in strategy. It was argued that a British presence would act as a counterbalance to the powerful and increasing U.S. presence in the Pacific.[4]

Constituent forces

The fleet was founded when Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser struck his flag at Trincomalee as Commander-in-Chief of the British Eastern Fleet and hoisted it in the gunboat HMS Tarantula as Commander-in-Chief British Pacific Fleet. He later transferred his flag to a more suitable vessel, the battleship HMS Howe.

The Eastern Fleet was based in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and reorganised into the British East Indies Fleet, subsequently becoming the British Pacific Fleet (BPF). The BPF operated against targets in Sumatra, gaining experience until early 1945, when it departed Trincomalee for Sydney. (These operations are described in the article on the British Eastern Fleet.)

The British provided the majority of the fleet's vessels and all the capital ships but elements and personnel included contributions from the British Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA), as well as the commonwealth nations, including the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN). With its larger vessels integrated with United States Navy formations since 1942, the RAN's contribution was limited. A high proportion of naval aviators were New Zealanders. The USN also contributed to the BPF, as did personnel from the South African Navy (SAN). Port facilities in Australia and New Zealand also made vital contributions in support of the British Pacific Fleet.

During World War II, the fleet was commanded by Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser. In practice, command of the fleet in action devolved to Vice-Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings, with Vice-Admiral Sir Philip Vian in charge of air operations by the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA). The fighting end of the fleet was referred to as Task Force 37 or 57 and the Fleet Train was Task Force 113. The 1st Aircraft Carrier Squadron was the lead carrier formation.

Fleet logistics

The requirement that the BPF be self-sufficient meant the establishment of a fleet train that could support a naval force at sea for weeks or months. The Royal Navy had been used to operating close to its bases in Britain, the Mediterranean or the Indian Ocean and infrastructure and expertise were lacking. In the north Atlantic and Mediterranean, the high risk of submarine and air attack would have made routine refuelling at sea highly dangerous. Fortunately for the BPF "the American logistics authorities... interpreted self-sufficiency in a very liberal sense".[5]

The Admiralty sent Vice Admiral Charles Daniel to the United States for consultation about the supply and administration of the fleet. He then proceeded to Australia where he became Vice Admiral, Administration, British Pacific Fleet, a role that "if unspectacular compared with command of a fighting squadron, was certainly one of the most arduous to be allocated to a British Flag officer during the entire war."[5] The US Pacific Fleet had assembled an enormous fleet of oilers and supply ships of every type. Even before the war, it had been active in the development of underway replenishment techniques. The Admiralty realised that it needed great deal of new equipment and training, in a short time and with whatever it had to hand. Lacking specialist ships, it had to improvise a fleet train from whatever RN, RFA or merchant ships were available. On 8 February 1944 the First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Alan Cunningham, informed the Defence Committee that 91 ships would be required to support the BPF. This was based on an assumption that the BPF would be active off the Philippines or would have a base there. By March, the war zone had moved north and the Americans were unwilling to allow the British to establish facilities in the Philippines. The estimate had grown to 158 ships, as it was recognised that operations eventually would be fought close to Japan. This had to be balanced against the shipping needed to import food for the civilian population of the UK. In January 1945, the War cabinet was forced to postpone the deployment of the fleet by two months due to the shortage of shipping.[6]

The BPF found that its tankers were too few, too slow and in some cases unsuitable for the task of replenishment at sea. Its oiling gear, hoses and fittings were too often poorly designed. British ships refuelled at sea mostly by the over-the-stern method, a safer but less efficient technique compared with the American method of refuelling alongside. Lack of proper equipment and insufficient practice meant burst hoses or excessive time at risk to submarine attack, while holding a constant course during fuelling.[7] As the Royal Australian Navy had discovered, British-built ships had only about a third of the refrigeration space of a comparable American ship. British ships therefore required replenishment more frequently than American ships.[8] In some cases even American-built equipment was not interchangeable, for FAA aircraft had been "Anglicized" by the installation of British radios and oxygen masks, while British Corsairs had their wing-folding arrangements modified in order to fit into the more cramped hangars of British carriers. Replacement aircraft therefore had to be brought from the UK.[9]

The British Chiefs of Staff decided early on to base the BPF in Australia rather than India, where there was famine and unrest over British colonial rule. While it was apparent that Australia, with its population of only about seven million could not support the projected 675,000 men and women of the BPF, the actual extent of the Australian contribution was undetermined. The Australian government agreed to contribute to the support of the BPF but the Australian economy was fully committed to the war effort and manpower and stores for the BPF could only come from taking them from American and Australian forces fighting the Japanese.[10] Unfortunately, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser arrived in Sydney on 10 December 1944 under the mistaken impression that Australia had asked for the BPF and promised to provide for its needs. Two days later, the Acting Prime Minister of Australia Frank Forde announced the allocation of £21,156,500 for the maintenance of the BPF. In January 1945, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur agreed to release American stockpiles in Australia to support the BPF. The Australian government soon became concerned at the voracious demands of the BPF works programme, which was criticised by Australian military leaders. In April 1945, Fraser publicly criticised the Australian government's handling of waterside industrial disputes that were holding up British ships. The government was shocked and angered but agreed to allocate £6,562,500 for BPF naval works. Fraser was not satisfied. On 8 August 1945 Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Clement Attlee felt obliged to express his regret for the misunderstandings to the Australian government.[11]

The distance from Sydney was too far to allow efficient fleet support so with much American support, a forward base was established at Manus atoll, in the Admiralty Islands, which was described as "Scapa Flow with bloody palm trees."[12]

As well as its base at Sydney, the Fleet Air Arm established Mobile Naval Air Bases (MONABs) in Australia to provide technical and logistic support for the aircraft. The first of these became active in Sydney in January 1945.[13]

Active service

Major actions in which the fleet was involved included Operation Meridian, air strikes in January 1945 against oil production at Palembang, Sumatra. These raids, conducted in bad weather, succeeded in reducing the oil supply of the Japanese Navy. A total of 48 FAA aircraft were lost due to enemy action and crash landings; they claimed 30 Japanese planes destroyed in dogfights and 38 on the ground.

The United States Navy (USN), which had control of Allied operations in the Pacific Ocean Areas, gave the BPF combat units the designation of Task Force 57 (TF-57) when it joined Admiral Raymond Spruance's United States Fifth Fleet on 15 March 1945.[14] On 27 May 1945, it became Task Force 37 (TF-37) when it became part of Admiral William Halsey's United States Third Fleet.[15]

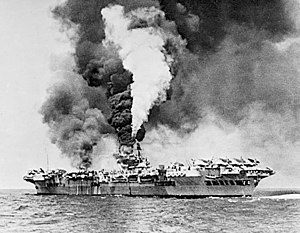

In March 1945, while supporting the invasion of Okinawa, the BPF had sole responsibility for operations in the Sakishima Islands. Its role was to suppress Japanese air activity, using gunfire and air attack, at potential Kamikaze staging airfields that would otherwise be a threat to U.S. Navy vessels operating at Okinawa. The carriers were subject to heavy and repeated kamikaze attacks, but because of their armoured flight decks, the British aircraft carriers proved highly resistant, and returned to action relatively quickly. The USN liaison officer on the Indefatigable commented: "When a kamikaze hits a U.S. carrier it means 6 months of repair at Pearl [Harbor]. When a kamikaze hits a Limey carrier it’s just a case of 'Sweepers, man your brooms.'”[16]

Fleet Air Arm Supermarine Seafires saw service in the Pacific campaigns. Due to their good high altitude performance and lack of ordnance-carrying capabilities (compared to the Hellcats and Corsairs of the Fleet) the Seafires were allocated the vital defensive duties of Combat Air Patrol (CAP) over the fleet. Seafires were thus heavily involved in countering the Kamikaze attacks during the Iwo Jima landings and beyond. The Seafires' best day was 15 August 1945, shooting down eight attacking aircraft for a single loss.

In April 1945, the British 4th Submarine Flotilla was transferred to the major Allied submarine base at Fremantle, Western Australia, as part of BPF. Its most notable success in this period was the sinking of the heavy cruiser Ashigara, on 8 June 1945 in Banka Strait, off Sumatra, by HMS Trenchant and HMS Stygian. On 31 July 1945, in Operation Struggle, the British midget submarine XE3, crewed by Lieutenant Ian Fraser, Acting Leading Seaman James Magennis, Sub-Lieutenant William James Lanyon Smith, RNZNVR, and Engine Room Artificer Third Class, Charles Alfred Reed, attacked Japanese shipping at Singapore. They sank the heavy cruiser Takao, which settled to the bottom at its berth. Fraser and Magennis were both awarded the Victoria Cross, Smith received the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and Reed the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM).

Battleships and aircraft from the fleet also attacked the Japanese home islands. The battleship King George V bombarded naval installations at Hamamatsu, near Tokyo; the last time a British battleship fired in action. Meanwhile, carrier strikes were carried out against land and harbour targets including, notably, the disabling of a Japanese escort carrier by British naval aircraft. Although, during the assaults on Japan, the British commanders had accepted that the BPF should become a component element of the U.S. 3rd Fleet, the U.S. fleet commander, William Halsey, excluded British forces from a raid on Kure naval base on political grounds.[17] Halsey later wrote, in his memoirs: "it was imperative that we forestall a possible postwar claim by Britain that she had delivered even a part of the final blow that demolished the Japanese fleet.... an exclusively American attack was therefore in American interests."

The BPF would have played a major part in a proposed invasion of the Japanese home islands, known as Operation Downfall, which was cancelled after Japan surrendered. The last naval air action in World War II was on VJ-Day when British carrier aircraft shot down Japanese Zero fighters.

Lt Robert Hampton Gray, a Canadian naval airman who piloted a Vought Corsair with 1841 Naval Air Squadron on HMS Formidable, was awarded the Victoria Cross, following his death in an attack on a Japanese destroyer at Onagawa Wan, Japan, on August 9, 1945.

Fighter squadrons from the fleet claimed a total of 112.5 Japanese aircraft shot down. 1844 Squadron NAS (flying Hellcats) was the top-scoring squadron, with 28 claims.

Allied co-operation

The conflicting British and American political objectives have been mentioned: Britain needed to "show the flag" in an effective way while the U.S. wished to demonstrate, beyond question, its own pre-eminence in the Pacific. In practice, there were cordial relations between the fighting fleets and their sea commanders. Although Admiral King had stipulated that the BPF should be wholly self-sufficient, in practice, material assistance was freely given: American officers told Rear Admiral Douglas Fisher, commander of the British Fleet Train, that he could have anything and everything “that could be given without Admiral King’s knowledge.” [18]

Post-war

Order of battle

The fleet included 17 aircraft carriers (with 300 aircraft), four battleships, 10 cruisers, 40 destroyers, 18 sloops, 13 frigates, 31 submarines, 35 minesweepers, other kinds of fighting ships, and many support vessels.

- Aircraft carriers

- HMS Colossus: 24 Corsairs, 18 Barracudas

- HMS Formidable: approximate airgroup 36 Corsairs, 15 Avengers

- HMS Glory: 21 Corsairs, 18 Barracudas

- HMS Illustrious: approximate airgroup 36 Corsairs, 15 Avengers

- HMS Implacable: 48 Seafire, 21 Avenger, 12 Firefly

- HMS Indefatigable: 40 Seafire, 18 Avenger, 12 Firefly

- HMS Indomitable: 39 Hellcats, 21 Avengers

- HMS Venerable: 21 Corsairs, 18 Barracudas

- HMS Vengeance: 24 Corsairs, 18 Barracudas

- HMS Victorious: 36 Corsairs, 15 Avengers, plus Walrus amphibian

- HMS Pioneer maintenance carrier for aircraft repair

- HMS Unicorn maintenance carrier for aircraft repair

- Escort Carriers

- HMS Arbiter

- HMS Chaser

- HMS Fencer

- HMS Ruler

- HMS Reaper

- HMS Slinger

- HMS Speaker

- HMS Striker

- HMS Vindex

- Battleships

- HMS Howe

- HMS King George V

- HMS Duke of York arrived in July 1945

- HMS Anson arrived in July 1945

- Cruisers

- HMNZS Achilles

- HMS Argonaut

- HMS Belfast

- HMS Bermuda

- HMS Black Prince

- HMS Euryalus

- HMNZS Gambia

- HMS Newfoundland

- HMCS Ontario

- HMS Swiftsure

- HMCS Uganda

- Cruiser-Minelayers

- AA Escort

- Destroyers

- HMCS Algonquin

- HMS Barfleur

- HMS Grenville

- HMS Kempenfelt

- HMAS Napier

- HMAS Nepal

- HMAS Nizam

- HMAS Norman

- HMS Quadrant

- HMS Quality

- HMAS Queenborough

- HMAS Quiberon

- HMAS Quickmatch

- HMS Teazer

- HMS Tenacious

- HMS Termagant

- HMS Terpsichore

- HMS Troubridge

- HMS Tumult

- HMS Tuscan

- HMS Tyrian

- HMS Ulster

- HMS Ulysses

- HMS Undaunted

- HMS Undine

- HMS Urania

- HMS Urchin

- HMS Ursa

- HMS Wager

- HMS Wakeful

- HMS Wessex

- HMS Whelp

- HMS Whirlwind

- HMS Wizard

- HMS Wrangler

- Frigates

- HMS Aire

- HMS Avon

- HMS Barle

- HMS Bigbury Bay

- HMS Derg

- HMS Findhorn

- HMS Helford

- HMS Odzani

- HMS Parret

- HMS Plym

- HMS Usk

- HMS Veryan Bay

- HMS Whitesand Bay

- HMS Widemouth Bay

- Sloops

- HMS Alacrity

- HMS Amethyst

- HMS Black Swan

- HMS Crane

- HMS Cygnet

- HMS Enchantress

- HMS Erne

- HMS Flamingo

- HMS Hart

- HMS Hind

- HMS Opossum,

- HMS Pheasant

- HMS Redpole

- HMS Starling

- HMS Stork

- HMS Whimbrel

- HMS Woodcock

- HMS Wren

- Corvettes

- HMNZS Arbutus

- HMAS Ballarat

- HMAS Bendigo

- HMAS Burnie

- HMAS Cairns

- HMAS Cessnock

- HMAS Gawler

- HMAS Geraldton

- HMAS Goulburn

- HMAS Ipswich

- HMAS Kalgoorlie

- HMAS Launceston

- HMAS Lismore

- HMAS Maryborough

- HMAS Pirie

- HMAS Tamworth

- HMAS Toowoomba

- HMAS Whyalla

- HMAS Wollongong

- Submarines

- HMS Porpoise Minelayer

- HMS Rorqual Minelayer

- HMS Sanguine

- HMS Scotsman

- HMS Sea Devil

- HMS Sea Nymph

- HMS Sea Scout

- HMS Selene

- HMS Sidon

- HMS Sleuth

- HMS Solent

- HMS Spark

- HMS Spearhead

- HMS Stubborn

- HMS Stygian

- HMS Supreme

- HMS Taciturn

- HMS Tapir

- HMS Taurus

- HMS Terrapin

- HMS Thorough

- HMS Thule

- HMS Tiptoe

- HMS Totem

- HMS Trenchant

- HMS Trump

- HMS Tudor

- HMS Turpin

- HMS Virtue Antisubmarine training

- HMS Voracious Antisubmarine training

- HMS Vox Antisubmarine training

- Landing Ships

- HMS Glenearn – Landing Ship, Infantry (Large)

- HMS Lothian – Landing Ship, Headquarters (Large)

- Fleet Train

- HMS Adamant Submarine depot ship

- HMS Aorangi Accommodation ship

- HMS Artifex Repair ship

- HMS Asistance Repair ship

- RFA Bacchus Distilling ship

- HMS Bonaventure Submarine depot ship

- HMS Berry Head Repair ship

- HMS Deer Sound Repair ship

- HMS Diligence Repair ship

- HMS Dullisk Cove Repair ship

- RNH Empire Clyde Hospital ship

- HMS Empire Crest Water carrier

- HMS Fernmore Boom carrier

- HMS Flamborough Head Repair ship

- HMS Fort Colville Aircraft store ship

- HMS Fort Langley Aircraft store ship

- RNH Gerusalemme Hospital ship

- HMS Guardian Netlayer

- HMNZS Kelantan Repair ship

- HMS King Salvor Salvage ship

- HMS Lancashire Accommodation ship

- HMS Leonian Boom carrier

- HMS Maidstone Submarine depot ship

- NZHS Maunganui Hospital ship

- HMS Montclare Destroyer Depot Ship

- RNH Oxfordshire Hospital ship

- HMS Resource Repair ship

- HMS Salvestor Salvage ship

- HMS Salvictor Salvage ship

- HMS Shillay Danlayer

- HMS Springdale Repair ship

- HMS Stagpool Distilling ship

- RNH Tjitalengka Hospital ship

- HMS Trodday Danlayer

- HMS Tyne Destroyer Depot Ship

- HMS Vacport Water carrier

- RNH Vasna Hospital ship

- Oilers

- RFA Arndale

- RFA Bishopdale

- RFA Brown Ranger

- RFA Cederdale

- RFA Eaglesdale

- RFA Green Ranger

- RFA Olna

- RFA Rapidol

- RFA Serbol

- RFA Wave Emperor

- RFA Wave Governor

- RFA Wave King

- RFA Wave Monarch

- Aase Maersk

- Carelia

- Darst Creek

- Golden Meadow

- Iere

- Loma Nova

- San Adolpho

- San Amado

- San Ambrosia

- Seven Sisters

- Store ships

- Bosporus

- City of Dieppe

- Corinda

- Darvel

- Edna

- Fort Alabama

- Fort Constantine

- Fort Dunvegan

- Fort Edmonton

- Fort Providence

- Fort Wrangell

- Gudrun Maersk

- Hermelin

- Heron

- Hickory Burn

- Hickory Dale

- Hickory Glen

- Hickory Steam

- Jaarstrom

- Kheti

- Kistna

- Kola

- Marudu

- Pacheco

- Prince de Liege

- Princess Maria Pia

- Prome

- Robert Maersk

- San Andres

- Sclesvig

- Thyra S

Template:Multicol-end Source: Smith, Task Force 57, pp. 178–184

Fleet Air Arm Squadrons

(Sources:[19][20])

(See List of Fleet Air Arm carrier air groups)

| Sqdn no | Aircraft type | Ship | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 801 | Seafire L.III | Implacable | May 1945 onwards | part of 8th Carrier Air Group |

| 812 | Barracuda II | Vengeance | departed Mediterranean July 1945 | en route to join BPF on VJ-Day |

| 814 | Barracuda II | Venerable | June 1945 onwards | 15th Carrier Air Group, saw no action |

| 820 | Avenger I | Indefatigable | embarked November 1944 with 849 squadron, and took part in the | with No 2 Strike Wing for attacks on oil refineries at Palembang, Sumatra and Sakashima Gunto islands; from June 1945 with 7th Carrier Air Group for strikes around Tokyo |

| 827 | Barracuda II | Colossus | embarked for BPF January 1945 | operated in the Indian Ocean from June 1945 until VJ-Day (BPF service unclear) |

| 828 | Barracuda I, II & III Avenger II |

Implacable | from June 1945 | part of 8th Carrier Air Group, involved in attacks on Truk and Japan |

| 837 | Barracuda II | Glory | embarked April 1945 | part of 16th Carrier Air Group but saw no action before VJ-Day; covered Japanese surrender at Rabaul |

| 848 | Avenger I | Formidable | April 1945 onwards | participated in strikes against Sakishima Gunto Island airfields and shore targets and on Formosa; in early June 1945 joined the 2nd Carrier Air Group for strikes on Japan in July |

| 849 | Avenger I & II | Victorious | December 1944 onwards | part of No 2 Naval Strike Wing for raids on Pangkalan Brandon and Palembang oil refineries, Sumatra in January 1945; strikes on the Sakashima Gunto islands and Formosa, strikes in July 1945 Japan, near Tokyo, where an 849 aircraft scored the first bomb hit on the carrier Kaiyo |

| 854 | Avenger I, II & III | Illustrious | December 1944 onwards | participated in strikes on Belawan Deli and Palembang; then took part in attacks on the Sakishima Gunto Islands; in July 1945 joined 3rd Carrier Air Group and saw no further action |

| 857 | Avenger I & II | Indomitable | November 1944 onwards | joined in attacks on Belawan Deli, Pangkalan Brandan and Palembang in December 1944 and January 1945; later 2 months continuous attacks on Sakishima Gunto islands and Formosa; no further action before VJ-Day, but subsequently combatted Japanese suicide boats on 31 August and 1 September 1945 near Hong Kong |

| 880 | Seafire L.III | Implacable | embarked March 1945 | escorted attacks on Truk island in June 1945; at end June merged into the new 8th Carrier Air Group; joined attacks in Japan |

| 885 | Hellcat I & II | Ruler | embarked December 1944 | provided fighter cover for the Fleet; aircraft reequipped June 1945, but saw no more action before VJ-Day |

| 887 | Seafire F.III & L.III | Indefatigable | embarked November 1944 | took part in attack on oil refineries at Palembang, Sumatra in January 1945; strikes on the Sakashima Gunto islands; strikes around Tokyo just before VJ-Day |

| 888 | Hellcat | Indefatigable | until January 1945 | operations over Sumatra, then remained in Ceylon when BPF departed |

| 894 | Seafire L.III | Indefatigable | embarked November 1944 | took part in operations against Palembang oil refineries in Sumatra, January 1945; in March and April 1945 attacked targets in the Sakishima Gunto islands, and then attacked the Japanese mainland just prior to VJ-Day. |

| 899 | Seafire L.III | Seafire pool | embarked HMS Chaser February 1945 | |

| 1770 | Firefly | Indefatigable | ||

| 1771 | Firefly | Implacable | ||

| 1772 | Firefly | Indefatigable | ||

| 1790 | Firefly NF | Vindex | from August 1945 | not in operational area before VJ-Day |

| 1830 | Corsair | Illustrious | ||

| 1831 | Corsair | Glory | ||

| 1833 | Corsair | Illustrious | ||

| 1834 | Corsair | Victorious | ||

| 1836 | Corsair | Victorious | ||

| 1839 | Hellcat | Indomitable | ||

| 1840 | Hellcat | Speaker | ||

| 1841 | Corsair | Formidable | ||

| 1842 | Corsair | Formidable | ||

| 1844 | Hellcat | Indomitable | ||

| 1846 | Corsair | Colossus | ||

| 1850 | Corsair | Vengeance | ||

| 1851 | Corsair | Venerable |

See also

Notes

- ^ Jackson, The British Empire and the Second World War, pp. 498–500

- ^ Arthur Bryant, Triumph in the West, pp.?

- ^ Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy, pp. 134–135

- ^ Jackson, The British Empire and the Second World War, p.500

- ^ a b Roskill, The War at Sea, Volume III, Part 2, p. 331

- ^ Roskill, The War at Sea, Volume III, Part 2, pp. 427–429

- ^ Ernest King and the British Pacific Fleet, pp. 121–122

- ^ Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942–1945, p. 103

- ^ Ernest King and the British Pacific Fleet, p. 120

- ^ Ehrman, Grand Strategy, Volume V: August 1943 – September 1944, pp. 469–475

- ^ Horner, High Command, pp. 377–381

- ^ England's Shadow Fleet: White Ensign in the Pacific

- ^ Roskill, The War at Sea, Volume III, Part 2, p. 429

- ^ Roskill, The War at Sea, Volume III, Part 2, p. 334

- ^ Morison, Victory in the Pacific, p. 272

- ^ Commander Dickie Reynolds

- ^ Sarantakes, Nicholase (1st quarter 2006). "The Short but Brilliant Life of the British Pacific Fleet" (pdf). JFQ / issue 40, p88. ndupress. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sarantakes, Nicholase (1st quarter 2006). "The Short but Brilliant Life of the British Pacific Fleet" (pdf). JFQ / issue 40, pp.86 & 87. ndupress. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Smith, Peter C. Task Force 57: British Pacific Fleet, 1944–45. pp. 184–185.

- ^ "NAVAL AIR SQUADRON INDEX (700–1800)". Fleet Air Arm Archive. Retrieved 16 Feb 2011.

References

- Bryant, Arthur; Brooke, Alan (1959). Triumph in the West, 1943–1946. London: Collins. OCLC 1005631.

- Churchill, Winston (1954). Volume VI: Triumph and Tragedy. The Second World War. London: Cassell. OCLC 15503601.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Ehrman, John (1956). Grand Strategy Volume V: August 1942 – September 1943. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 217257928.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-417-0. OCLC 62089366.

External links

- Fleet Air Arm Archive, 2000–01, British Pacific Fleet 1945

- Supplement to the London Gazette of Tuesday, the 1st of June, 1948, "The Contribution of the British Pacific Fleet to the Assault on Okinawa, 1945." (Published June 2, 1948.)

- The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945 (1956), Ch. 24: "With the British Pacific Fleet"

- Ted Bates, 200?, British Pacific Fleet

- The Short but Brilliant Life of the British Pacific Fleet, Nicholase Sarantakes

- Fleets of the Royal Navy

- History of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Naval history of Canada

- Military units and formations of the Royal Navy in World War II

- Military units and formations established in 1944

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1945

- 1944 establishments in the United Kingdom

- 1945 disestablishments in the United Kingdom

- History of the Pacific Ocean