Anders Behring Breivik

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (January 2025) |

Anders Behring Breivik Fjotolf Hansen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Anders Behring Breivik 13 February 1979 Oslo, Norway |

| Other names |

|

| Political party | Progress Party (1999–2006) |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Trial | Trial of Anders Behring Breivik |

| Criminal penalty | 21 years' preventive detention |

| Details | |

| Date | 22 July 2011 Oslo: 15:25 CEST Utøya: 17:22–18:34 CEST[1][2] |

| Location(s) | Oslo and Utøya, Norway |

| Target(s) | Norwegian Labour Party members and teenagers |

| Killed | 77 (8 in Oslo, 69 on Utøya) |

| Injured | 319[3] |

| Weapons | ANFO car bomb Ruger Mini-14 rifle Glock 34 pistol |

| Imprisoned at | Ringerike Prison |

Fjotolf Hansen[4] (born 13 February 1979), better known by his birth name Anders Behring Breivik (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈɑ̂nːəʂ ˈbêːrɪŋ ˈbræ̂ɪviːk] ⓘ),[5] is a Norwegian neo-Nazi[12] terrorist.[13] He carried out the 2011 Norway attacks in which he killed eight people by detonating a van bomb at Regjeringskvartalet in Oslo, and then killed 69 participants of a Workers' Youth League (AUF) summer camp, in a mass shooting on the island of Utøya.[14][15]

After Breivik was found psychologically competent to stand trial, his criminal trial was held in 2012.[16] That year, Breivik was found guilty of mass murder, causing a fatal explosion, and terrorism.[17][18] Breivik was sentenced to the maximum civilian criminal penalty in Norway, which is 21 years' imprisonment through preventive detention, allowing the possibility of one or more extensions for as long as he is deemed a danger to society.[19]

At the age of 16 in 1995, Breivik was arrested for spraying graffiti on walls.[20][21] He was not chosen for conscription into the Norwegian Armed Forces. At the age of 20, he joined the anti-immigration Progress Party, and chaired the local Vest Oslo branch of the party's youth organization in 2002. He joined a gun club in 2005.[22] He left the Progress Party in 2006. A company he founded was later declared bankrupt.[23] He had no declared income in 2009 and his assets were 390,000 kroner (equivalent to $72,063),[24] according to Norwegian tax authority figures.[25] He financed the terror attacks with a total of €130,000;[25] nine credit cards gave him access to credit.[26]

On the day of the attacks, Breivik emailed a compendium of texts entitled "2083: A European Declaration of Independence", describing his militant ideology.[27][28][29][30] In them, he stated his opposition to Islam and blamed feminism for a European "cultural suicide."[31][32] The text called for the deportation of all Muslims from Europe,[33][34] and Breivik wrote that his main motive for the attacks was to publicize his manifesto.[35] Two teams of court-appointed forensic psychiatrists examined Breivik before his trial. The first team diagnosed Breivik with paranoid schizophrenia,[36] but after this initial finding was criticized,[37] a second evaluation concluded that he was not psychotic during the attacks but did have narcissistic personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder.[38][39]

In 2016, Breivik won a partial victory in a lower court;[40] however, the case was lost on appeal in a higher court. Other than that, Breivik has repeatedly but unsuccessfully sued the Norwegian Correctional Service and appealed to the European Convention on Human Rights over solitary confinement and refusal of parole, which Breivik claims violated his human rights.

In December 2024, a five-day trial took place in a court of appeals[41][42] as Breivik sued the Government of Norway for violating his human rights by keeping him in prison isolation.[43][44][45]

Early life and reports of abuse

[edit]Breivik was born in Oslo on 13 February 1979,[46][47] the son of Jens David Breivik (born 1935), a civil economist, who worked as a diplomat for the Norwegian Embassy in London and later in Paris, and Wenche Elisabeth Behring (1946–2013), a nursing assistant. He has a maternal half-sister named Elisabeth, and three paternal half-siblings: Erik, Jan, and Nina.[48] Breivik began his life in London until the age of one, when his parents divorced. His family name is Breivik, while Behring, his mother's maiden name, is his middle name and not part of the family name. In 2017, it was reported he had changed his legal name to Fjotolf Hansen.[49]

When Breivik was aged four and living in Oslo's Frogner borough, two reports were filed expressing concern about his mental health.[50] A psychologist in one report made a note of the boy's peculiar smile, suggesting it was not anchored in his emotions but was rather a deliberate response to his environment.[51] In another report from Norway's National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (SSBU), concerns were raised about how Breivik was treated by his mother: "[s]he 'sexualised' the young Breivik, hit him, and frequently told him that she wished that he were dead."

In the report, Wenche Behring is described as "a woman with an extremely difficult upbringing, borderline personality disorder and an all-encompassing if only partially visible depression" who "projects her primitive aggressive and sexual fantasies onto him [Breivik]".[52] The report recommended he be forcibly removed from his mother and placed into foster care, as she was heavily emotionally and psychologically abusive towards him, but this was not carried out by the Child Welfare Service.[53][54]

Breivik's mother had fled her abusive home at age 17 and soon after that became a teenage mother. In her thirties, she became pregnant with Anders and married his father, Jens Breivik. During her pregnancy, she moved to London, where Jens worked.[54] Even before his birth, Breivik's mother developed a disdain for her son. She claimed that he was a "nasty child" and that he was "kicking her on purpose". She had wanted to abort him but by the time she went to a hospital, she had passed the three-month threshold for an abortion. Psychologist reports later stated that she thought that Breivik was a "fundamentally nasty and evil child and determined to destroy her." She stopped breastfeeding her son early on because he was "sucking the life out of her".[54]

A year after Breivik's birth, his parents' relationship ended. Breivik's mother moved back to Oslo, where she borrowed[55] Jens Breivik's apartment in the Frogner borough. Neighbours claimed that there were noises of fights and that the mother left her children completely alone for extended periods of time, while she was working as a nurse. In 1981, Breivik's mother applied for welfare spending benefits, specifically monetary payment or financial aid;[55] in 1982, she applied for respite care for her son. She says that she was overwhelmed with the boy and unable to care for him. She described him as "clingy and demanding". Breivik was then placed, in cooperation with the Child Welfare Service, with a young couple. This couple later told police that the mother, when bringing two-year-old Breivik to the house, had asked that he be allowed to touch the man's penis because he had no one to compare himself to in terms of appearance; "He has only ever seen girls' parts", the mother told the couple, according to the couple's undated statement to police.[56]

In February 1983, on the advice of her neighbours, Breivik's mother sought help from the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (SSBU); Breivik and his mother were outpatients, and they stayed there during the daytime for about one month. The psychiatrists' conclusion of the stay was that Breivik should be placed in the foster care system and had to be removed from his mother for him to develop normally. This was based on several observations: Breivik had little emotional engagement and neither showed joy nor cried when he was hurt; he also made no attempts to play with other children, was extremely clean, and became anxious when his toys were not in order.

Psychologists believed that Breivik's mother had punished him and reacted extremely negatively to him displaying emotions leading him to become devoid of any visible emotions. His mother had also claimed that he was unclean and that she constantly had to care for him. Psychologists believed that Breivik had developed obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) because of fear of punishment from his mother. He did not show the normal level of uncleanliness of a four-year-old and had no repertoire on how to express emotions normally. On rare occasions, his long phases of emotional voidness would be interrupted by fits where he would erupt and display extreme uncontrolled emotions.[54]

Reports of the staff said that his mother had told Breivik that she "wished that he was dead" while she knew that she was being observed by health personnel. At the same time she bound him emotionally to her, alternating between great affection and extreme cruelty from one moment to the next. Some nights, Breivik and his mother would share the bed with close body contact.[57] The psychiatrists concluded this was an unacceptable situation for a four-year-old to be in and the report from 1983 stated: "Anders is a victim of his mother's projections of paranoid-aggressive and sexual fears toward men in general", and "she projects onto him her own primitive, aggressive and sexual fantasies; all the qualities in men that she regards as dangerous and aggressive." Breivik reacted very negatively to his mother and alternated between clinginess, petty aggression and extreme childishness.[54]

The final conclusion of the observation was that the "family is in dire need of help. Anders should be removed from the family and given a better standard of care; the mother is provoked by him and remains in an ambivalent position which prevents him from developing on his own terms. Anders has become an anxious, passive child that averts making contact. He displays a manic defense mechanism of restless activity and a feigned, deflecting smile. Considering the profoundly pathological relationship between Anders and his mother it is crucial to make an early effort to ward off a severely skewed development in the boy." However, Child Welfare Services did not follow this recommendation and instead, he was placed in respite care only during the weekends.[54]

When Breivik's father learned of the situation, he filed for custody. Although Breivik's mother had agreed to have him put in respite care, after Jens had filed for custody she demanded that Breivik be put back into full custody with her. Both the mother and father involved lawyers and eventually, the case was dropped because the Welfare Services thought that they would not be able to provide enough evidence in court to warrant the placement of Breivik in foster care. One of the main reasons for this was the testimony of staff from the Vigelandsparken Nursery, which Breivik had been attending since 1981, who both described him as a happy child and claimed that nothing was or had been wrong with him all along.

The SSBU, however, maintained their stance regarding Breivik, going so far as to state that "urgent action is crucially needed to prevent a severely skewed development in the boy". The SSBU wrote Child Welfare Services a letter claiming that an order should be placed to have Breivik removed by force. In 1984, a hearing in front of Barnevernsnemnda (the municipal child welfare committee) took place on whether Breivik's mother should lose custody of him. The Child Welfare Service lost the case; the agency was represented by a social worker with no prior experience representing a case in front of the committee.[55] It was ruled only that the family should be supervised; however, after only three visits, even this supervision was discontinued. Breivik was never again put into respite care or foster care.[54]

Later childhood and adolescence

[edit]Breivik attended Smestad Grammar School, Ris Junior High, Hartvig Nissens School and Oslo Commerce School.[58][59] A former classmate recalled that Breivik was an intelligent student, physically stronger than others of the same age, who often took care of people who were bullied.[60] Breivik lived with his mother and his elder half-sister in the West End of Oslo,[61][55] regularly visiting his father and stepmother, who had now moved to France, until they divorced when he was 12. His mother remarried to an officer in the Norwegian Army.[50] Breivik chose to be confirmed into the Lutheran Church of Norway at the age of 15.[62][63][64][65]

In his adolescence, Breivik's behaviour was described as rebellious. In his early teen years, he was a prolific graffiti artist and part of the hip hop community in Oslo West. He took his graffiti much more seriously than his associates did and was caught by the police on several occasions; child welfare services were notified once again and he was fined on two occasions.[20] According to Breivik's mother, his father ceased contact with him at the age of 15 after he was caught and fined for spraying graffiti on walls in 1995.[20][21] It was reported they had not been in contact since then.[66] According to Breivik's father, however, it was his son who broke off contact, claiming "I was always willing to see [Anders]," despite his destructive activities.[67] At this age, Anders fell out with his best friend and broke off contact with the hip-hop community.[68]

Beginning in adolescence, Breivik spent his spare time weight training and started to use anabolic steroids. He cared a lot about his looks and about appearing big and strong.[69]

Adulthood

[edit]Breivik was exempt from conscription to military service in the Norwegian Army; he had no military training.[70] The Norwegian Defence Security Department, which conducts the vetting process, says he was deemed "unfit for service" at the mandatory conscript assessment.[71] After age 21, Breivik worked in the customer service department of an unnamed company, working with "people from all countries" and being "kind to everyone".[25] A former co-worker described him as an "exceptional colleague",[72] while a close friend of his said he usually had a big ego.

Breivik is reported to have travelled extensively and visited up to 24 countries in the years before the attacks,[73] including Belarus in 2005.[74] Norwegian prosecuting authorities claim that Breivik went to Belarus to meet a woman he had met on a dating website. The same woman later visited him in Oslo.[75] Norwegian police sent legal requests to sixteen countries to investigate Breivik following his attacks.[76] According to acquaintances, in his early twenties Breivik had cosmetic surgery on his chin, nose and forehead, and was pleased with the results.[69]

2011 terror attacks

[edit]Planning

[edit]

Breivik claimed that in 2002, at the age of 23, he started a nine-year plan to finance the 2011 attacks, forming his own computer programming business while working at a customer service company. He claimed his company grew to six employees and "several offshore bank accounts", and that he had made his first million kroner at the age of 24. He wrote in his manifesto that he lost 2 million kroner on stock speculation, but still had about 2 million kroner to finance the attack.[26] The company was later declared bankrupt and Breivik was reported for several breaches of the law.[23] He then moved back to his mother's home in order to save money. The first set of psychiatrists who evaluated him said in their report that his mental health deteriorated at this stage and he entered a state of withdrawal and isolation.[77] His declared assets in 2007 were about kr 630,000 (US$76,244[24]), according to Norwegian tax authority figures.[25] He claimed that by 2008 he had about kr 2,000,000 (US$243,332[24]) and nine credit cards giving him access to €26,000 in credit.[26]

In May 2009, he founded a farming company called "Breivik Geofarm",[78] described as a farming sole proprietorship set up to cultivate vegetables, melons, roots, and tubers.[79] In 2010, he visited Prague in an attempt to buy illegal weapons. He was unable to obtain a weapon there and decided to use legal channels in Norway instead.[80] He bought one semi-automatic 9 mm Glock 34 pistol legally by demonstrating his membership in a pistol club in the police application for a gun license, and the semi-automatic Ruger Mini-14 rifle by possessing a hunting license.[81] Breivik had no declared income in 2009 and his assets amounted to 390,000 kroner ($72,063),[24] according to Norwegian tax authority figures.[25] He stated that in January 2010 his funds were "depleting gradually". On 23 June 2011, a month before the attacks, he paid the outstanding amount on his nine credit cards so he could have access to funds during his preparations.[26] Breivik had covered up the windows of his house. Breivik's former neighbour described him as a "city dweller, who wore expensive shirts and who knew nothing about rural ways". The owner of a local bar, who once worked as a profiler of passengers' body language at Oslo Airport, said there was nothing unusual about Breivik, who was an occasional customer at the bar.[82]

In late June or early July 2011, he moved to a rural area north of Åsta in Åmot, Innlandet county, about 140 km (87 mi) north-east of Oslo,[83] the site of his farm. According to his manifesto, Breivik used the company as a cover to legally obtain large amounts of artificial fertiliser and other chemicals for the manufacturing of explosives.[83] A farming supplier sold Breivik's company six tonnes of fertiliser in May.[84] The newspaper Verdens Gang reported that after Breivik bought a small quantity of an explosive primer from an online shop in Poland, his name was among sixty passed to the Police Security Service (PST) by the Norwegian Customs Service as having used the store to buy products. Speaking to the newspaper, Jon Fitje of PST said the information they found gave no indication of anything suspicious. He sets the cost of the preparations for the attacks at €317,000—"130,000 out of pocket and 187,500 euros in lost revenue over three years." [sic][25]

The attacks

[edit]

The first attack was a car bomb explosion in Oslo within Regjeringskvartalet, the executive government quarter of Norway, at 15:25:22 (CEST) on 22 July 2011.[85] The bomb was placed inside a van[86] next to the tower block housing the office of then Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg.[87] The explosion killed eight people and injured at least 209 people, twelve severely.[88][89][90]

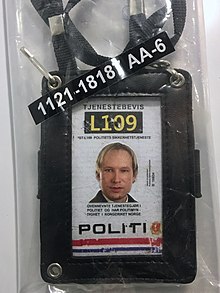

The second attack occurred less than two hours later at a youth summer camp on the island of Utøya in Tyrifjorden, Buskerud. The camp was organised by the AUF, the youth wing of the ruling Norwegian Labour Party (AP). Breivik, dressed in a homemade police uniform and showing false identification,[91][92] took a ferry to the island and opened fire at the participants, methodically killing 69[93][94] and injuring 32 over more than an hour.[89][90] Among the dead were friends of Stoltenberg, and the stepbrother of Norway's crown princess Mette-Marit.[95]

Arrest

[edit]When the police tactical unit Delta based in Oslo arrived on the island and confronted him, he surrendered without resistance.[96] After his arrest he was held on the island and interrogated throughout the night, before being moved to a holding cell in Oslo. Breivik admitted to the crimes and said the purpose of the attack was to save Norway and Western Europe from a Muslim takeover, and that the Labour Party had to "pay the price" for "letting down Norway and the Norwegian people."[97] After his arrest, Breivik referred to himself as "the greatest monster since Quisling."[98]

Booking and preparations for trial

[edit]On 25 July 2011, Breivik was charged with violating paragraph 147a of the Norwegian criminal code,[99][100] "destabilising or destroying basic functions of society" and "creating serious fear in the population",[101] both of which are acts of terrorism under Norwegian law. He was held for eight weeks, the first four in solitary confinement, pending further court proceedings.[99][102] The custody was extended in subsequent hearings.[103] The indictment was ready in early March 2012. The Director of Public Prosecutions had initially decided to censor the document to the public, leaving out the names of the victims as well as details about their deaths. Due to the public's reaction, this decision was reversed prior to its release.[104] On 30 March, the Borgarting Court of Appeal announced that it had scheduled the expected appeal case for 15 January 2013. It would be heard in the same specially-constructed courtroom where the initial criminal case was tried.[105]

Breivik was kept at Ila Detention and Security Prison after arrest. There, he had at his disposal three prison cells: one where he could rest, sleep, and watch DVDs and TV, a second that was set up for him to use a computer without the Internet, and a third with gymnasium equipment. Only selected prison staff with special qualifications were allowed to work around him, and the prison management aimed to not let his presence as a high-security prisoner affect any of the other inmates.[106] Subsequent to the January 2012 lifting of letters and visitors censorship for Breivik, he received several inquiries from private individuals,[107] and he devoted his time to writing back to like-minded people. According to one of his attorneys, Breivik was curious to learn whether his manifesto has begun to take root in society. Breivik's attorneys, in consultation with Breivik, considered whether to have some of his interlocutors called as witnesses during the trial.[108] Media outlets, both Norwegian and international, requested to interview Breivik. The first such was cancelled by the prison administration following a background check of the journalist in question. A second interview was agreed to by Breivik, and the prison requested a background check to be done by the police in the country of the journalist. No information was divulged about the media organisations in question.[109]

Psychiatric evaluation

[edit]Breivik underwent his first examination by court-appointed forensic psychiatrists in 2011. The psychiatrists diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia, concluding that he had developed the disorder over time and was psychotic both when he carried out the attacks and during the observation. He was also diagnosed with abuse of non-dependence-producing substances antecedent of 22 July. The psychiatrists consequently found Breivik to be criminally insane.[110][111]

According to the report, Breivik displayed inappropriate and blunted affect and a severe lack of empathy. He spoke incoherently in neologisms and had acted compulsively based on a universe of bizarre, grandiose and delusional thoughts. Breivik alluded to himself as the future regent of Norway, master of life and death, while calling himself "inordinately loving" and "Europe's most perfect knight since WWII". He was convinced that he was a warrior in a "low-intensity civil war" and had been chosen to save his people. Breivik described plans to carry out further "executions of categories A, B and C traitors" by the thousands, the psychiatrists included, and to organize Norwegians in reservations for the purpose of selective breeding. Breivik believed himself to be the "knight Justiciar grand master" of a Templar organisation. He was deemed to be suicidal and homicidal by the psychiatrists.[110] According to his defence attorney, Breivik initially expressed surprise and felt insulted by the conclusions in the report. He later said "this provides new opportunities".[112]

The outcome of Breivik's first competency evaluation was fiercely debated in Norway by mental health experts, over the court-appointed psychiatrists' opinion and the country's definition of criminal insanity.[113][114] An extended panel of experts from the Norwegian Board of Forensic Medicine reviewed the submitted report and approved it "with no significant remarks".[115] News in the meantime emerged that the psychiatric medical staff in charge of treating prisoners at Ila Detention and Security Prison did not make any observations that suggested he had either psychosis, depression or was suicidal. According to senior psychiatrist Randi Rosenqvist, who was commissioned by the prison to examine Breivik, he rather appeared to have personality disorders.[114][116][117]

Counsels representing families and victims filed requests that the court order a second opinion, while the prosecuting authority and Breivik's lawyer initially did not want new experts to be appointed. On 13 January 2012, after much public pressure, the Oslo District Court ordered a second expert panel to evaluate Breivik's mental state.[118] He initially refused to cooperate with new psychiatrists.[119] He later changed his mind and in late February a new period of psychiatric observation, this time using different methods than the first period, was begun.

If the original diagnosis had been upheld by the court, it would have meant that Breivik could not be sentenced to a prison term. The prosecution could instead have requested that he be detained in a psychiatric hospital.[120] Medical advice would then have determined whether or not the courts decided to release him at some later point. If considered a perpetual danger to society, Breivik could have been kept in confinement for life.[121] Shortly after the second period of pre-trial psychiatric observation was begun, the prosecution said it expected Breivik would be declared legally insane.[122][123]

On 10 April 2012, the second psychiatric evaluation was published with the conclusion that Breivik was not psychotic during the attacks and he was not psychotic during their evaluation.[38] Instead, they diagnosed antisocial personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder.[39][124][125] Breivik expressed hope at being declared sane in a letter sent to several Norwegian newspapers shortly before his trial, in which he wrote about the prospect of being sent to a psychiatric ward: "I must admit this is the worst thing that could have happened to me as it is the ultimate humiliation. To send a political activist to a mental hospital is more sadistic and evil than to kill him! It is a fate worse than death."[126]

On 8 June 2012, Professor of Psychiatry Ulrik Fredrik Malt testified in court as an expert witness, saying he found it unlikely that Breivik had schizophrenia. According to Malt, Breivik primarily had Asperger syndrome, Tourette syndrome, narcissistic personality disorder and possibly paranoid psychosis.[127] Malt cited a number of factors in support of his diagnoses, including deviant behaviour as a child, extreme specialization in Breivik's study of weapons and bomb technology, strange facial expression, a remarkable way of talking, and an obsession with numbers.[128] Eirik Johannesen disagreed, concluding that Breivik was lying and was not delusional or psychotic.[129] Johannesen had observed and spoken to Breivik for more than twenty hours.[130]

Pre-trial hearing

[edit]In the pre-trial hearing, in February 2012, Breivik read a prepared statement demanding to be released and treated as a hero for his "pre-emptive attack against traitors" accused of planning cultural genocide. He said, "They are committing, or planning to commit, cultural destruction, including deconstruction of the Norwegian ethnic group and deconstruction of Norwegian culture. This is the same as ethnic cleansing."[131]

Criminal trial and conviction

[edit]The criminal trial of Breivik began on 16 April 2012 in Oslo Courthouse under the jurisdiction of Oslo District Court. The appointed prosecutors were Inga Bejer Engh and Svein Holden with Geir Lippestad serving as Breivik's lead counsel for the defence. Closing arguments were held on 22 June.[16] On 24 August 2012, Breivik was adjudged sane at the time the crimes were committed and sentenced to preventive detention for a period of 21 years—the maximum penalty in Norway; with a minimum non-parole period of 10 years which is the longest minimum sentence available.[132][133] This sentence allows the court to continue Breivik's detention indefinitely, five years at a time for as long as the prosecuting authority deems it necessary in order to protect society. Whilst Breivik pleaded not guilty, Breivik did not appeal the sentence, and on 8 September, the media announced that the verdict was final.[134][135]

Breivik announced that he did not recognize the legitimacy of the court and therefore did not accept its decision—he decided not to appeal, saying this would legitimize the authority of the Oslo District Court.[136][134]

Prison life

[edit]

Since August 2011, Breivik has been imprisoned in an SHS section (a prison section with "particularly high security"—"særlig høy sikkerhet").[138][139] In March 2022, Breivik was transferred to Ringerike Prison;[140] as of 2022[update], he is in an SHS section. There is another prisoner in the section, but Breivik is completely[141] separated from that prisoner.[142][143][144][145] Breivik's earlier prison transfers consisted of his being transferred on 23 July 2012 from Ila Detention and Security Prison in Bærum[146] to Skien Prison, formally known as Telemark fengsel, Skien avdeling, in Skien, county Telemark,[147] and his being transferred back to Ila on 28 September 2012.[138]

In 2023, Breivik chose to put a stop[148] to receiving further prison visitor visits including from the military chaplain (ranked major) that Breivik had been seeing every two weeks since[149] 2015.[150][151] His mother visited him five times before her death in 2013[152] and researcher Mattias Gardell interviewed Breivik in 2014,[153] but no other visitor requested by Breivik has been granted access.[152]

Breivik is isolated from the other inmates and only has contact with healthcare workers and guards.[154] The type of isolation that Breivik has experienced in prison is what the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) calls relative social isolation, according to a verdict of 2016 in Oslo District Court.[152] In November 2020, Breivik had an interaction with another prisoner for the first time, in the presence of at least seven prison officers; the prisoners played cards and talked for around one or two hours; the other prisoner chose to not have a third meeting with Breivik, according to media reports in January 2021.[155]

In Norway, it is not uncommon to grant compensatory measures to prisoners who are being held in isolation for several years. As of 2021[update], he has access in his cell -between 9 am and 2:30 pm—to a personal computer (with seals that impede unauthorised opening of the computer panels), that he uses to write letters.[156] Earlier reports—in 2016—said that he has an electric typewriter and an Xbox (without internet connection) in his cell.[157] Previously, when the original verdict was upheld in September 2012, his permission for access to a computer (without internet) in his prison cell ended.

Breivik enrolled in a bachelor's degree program in political science at the University of Oslo; he passed two courses in 2015.[158][159][160] In 2015, he claimed in a letter that harsh prison conditions had forced him to drop out.[161] According to a statement by his lawyer, Breivik had become a Nazi in prison.[162] The government denied him parole in Q3 2024. An earlier decision saw the government denying him parole in 2021, and the court system upheld that decision in 2022.[163][164] Since his imprisonment, Breivik has identified himself as a fascist[165] and a Nazi,[166] as well as a practitioner of Odinism.[166][167][168]

Political activity and attempts at correspondence

[edit]As of 2012, Breivik has written to, among others, Peter Mangs and Beate Zschäpe.[169][153][170][171] In 2012, politicians protested Breivik's activities in prison, which they see as him continuing to promote or expose his ideology and possibly encouraging further criminal acts.[170][171][172] As with all convicts, his letters are vetted before sending to prevent further crimes. After he came to Skien Prison in 2013,[138] 5 out of 300 letters that he sent had not been confiscated, he testified in court in 2016.[151] By 2016, around 4,000 postal items had been sent to or from Breivik, and about 15 per cent of these (600 items) had been confiscated.[173]

Complaints about prison conditions

[edit]In November 2012, Breivik wrote a 27-page letter of complaints to the prison authorities, talking about the security restrictions he was being held under, claiming that the prison director personally wanted to punish him. In 2014 Breivik threatened to starve himself were his latest list of demands refused; these included "access to a sofa and a bigger gym" and better video games.[174][175] In September 2015, Breivik again threatened a hunger strike because of deteriorating prison conditions,[161] but delayed in order to sue the Norwegian Government over prison conditions.[154]

2016 civil trial against Norwegian government

[edit]Breivik sued the government of Norway; the civil trial was held in March 2016.[176] The verdict in the lower court was appealed;[177] in the appellate court, he lost on all counts, and the supreme court decided not to hear the case.[178][179][180]

Breivik sued the government over his solitary confinement, and his general conditions of imprisonment, including a claim of an excessive use of handcuffs, frequent strip searches and searches of his cell, including at night.[181]

At the start of the trial, Breivik gave a Nazi salute.[182] In his testimony, Breivik claimed prison conditions and isolation damaged his health.[183][184][151][151]

The government attorney said "the government's primary task is to protect its citizens. To let a convicted terrorist establish a network is dangerous".[185]

On 20 April 2016, the District Court's verdict[186] said that the conditions of Breivik's imprisonment breached Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, but that Article 8 of the Convention had not been violated—confiscation of letters had been justified.[187]

The verdict in the appeal case handed down in March 2017[178][179] stated that the conditions of his imprisonment did not violate Breivik's rights, and all recommendations were voided.[180] In 2017, Norway's Supreme Court decided not to hear the case.[188][189]

2022 criminal trial resulting from parole petition

[edit]In January 2022 a trial was initiated to decide whether to reverse or uphold the District Attorney's refusal of parole.[190][191][192][193][194][195] The indictment states that the prosecuting authority does not consent to parole because "preventive detention is deemed necessary to protect society".[192][196]

At the start of the trial, Breivik gave several Nazi salutes.[197][198] Breivik testified that he is still a Nazi and will continue to work for White Power, but no longer wants to pursue it through violence.[192][199][159]

The verdict said that Breivik appeared to be "obviously mentally disturbed, and with a mind that is difficult for other people to penetrate".[200][201][202][163]

Some psychiatrists watched media broadcasts from the trial and claimed that Breivik appeared to be mentally ill,[203][204] in particular that he appeared to be psychotic and delusional.[205][203][206] Another forensic psychiatrist disagreed with comments that Breivik was psychotic and said he may have autism.[206]

January 2024 civil trial against Norwegian government

[edit]On 8 January 2024, the court convened inside Breivik's prison; the lawsuit accuses the government of negatively affecting[207] Breivik's mental health by depriving him of contact with others.

The prosecution discussed how Breivik's two latest risk evaluations conclude that Breivik is still viewed as a great risk to others.[208]

In his testimony, Breivik said "many years have passed since I had any meaningful relationships",[209][207] that he is using antidepressants, and that he is struggling with thoughts about taking his own life.[207][208]

When asked how he views his 2011 attack, Breivik replied that "I was radicalised over two years. I am very sorry about my actions".[208]

In a report by PST that was referred to in court, Breivik is characterised as a "saint" in international circles of the extreme right. Breivik said that "PST is not saying that I am still dangerous, but they are saying that I have an inspirational effect.".[207]

The government prosecutor said that Breivik's prison conditions are much better than what was said in court.[210][208]

Some journalists observed that unlike in previous trials, Breivik did not try to spread propaganda or make Nazi salutes.[209][211]

Breivik's lawyer claims that the Norwegian government is violating Breivik's human rights regarding prohibitions against torture and inhumane treatment, and for having violated Breivik's rights regarding personal life and family life.[212]

The trial ended on 12 January 2024.[213] On 15 February, it was determined his human rights were not being violated and he will still be kept under isolation.[44][45] The trial in court of appeal was scheduled for December 2024.

November 2024 criminal trial resulting from parole petition

[edit]This section needs expansion with: Information about the trial, but without excessive details. You can help by adding to it. (January 2025) |

In April 2024, the court suggested that the trial regarding the possibility for parole be postponed until November. A psychologist who has been an expert witness in Breivik's trial in January was in a relationship with the main government attorney. The government replaced the expert witnesses.[214][215][216]

Day Two of the trial was on 19 November 2024.[215][217][218]

Breivik testified (and was allotted 45 minutes).[219]

Breivik lost the November trial;[220] he can appeal.[221]

Financing of legal aid and family situation

[edit]Breivik is receiving pro bono legal aid (as of 2024) from the law firm of Øystein Storrvik—his lawyer since 2014.[201][222][223] Previously, the firm of Geir Lippestad did pro bono representation of Breivik after the 2012 trial.[224] Legal aid during criminal trials has been paid by the government, as is the norm in the country.

On 23 March 2013, Breivik's mother died from complications from cancer.[225] On the same day media said that mother and son "took farewell during a meeting at Ila last week. Breivik was permitted to move himself out from behind the glass wall of the visit room—to give his mother a farewell hug".[226] Breivik asked prison officials for permission to attend his mother's funeral service;[227] permission was denied.[228]

Writings and video

[edit]Forums and YouTube

[edit]Janne Kristiansen, then Chief of the Norwegian Police Security Service (PST), said Breivik "deliberately desisted from violent exhortations on the net [and] has more or less been a moderate, and has neither been part of any extremist network."[229] He is reported to have written many posts on the far-right anti-Muslim website document.no.[230] He also attended a meeting of "Documents venner" (Friends of Document), affiliated with the website, in late 2009,[231] and reportedly sought to start a Norwegian version of the Tea Party movement in cooperation with the owners of document.no.[232]

After expressing initial interest, they turned down his proposal because he did not have the contacts he promised.[232] Due to the media attention on his Internet activity following the 2011 attacks, document.no compiled a complete list of comments made by Breivik on its website between September 2009 and June 2010.[233] Breivik was also very active writing on the neo-Nazi websites Stormfront—with several thousand posts[234]—and nordisk.nu,[235] as well as mainstream newspapers such as Verdens Gang and Aftenposten.[236]

Six hours before the attacks, Breivik posted a picture of himself as a Knight Templar officer in a uniform festooned with a gold aiguillette and multiple medals he had not been awarded.[237] In the video, he included an animation depicting Islam as a Trojan Horse in Europe.[238] The video, which promotes fighting against Islam, shows Breivik wearing a wetsuit and holding a semi-automatic weapon.[239]

Manifesto – 2083: A European Declaration of Independence

[edit]Content

[edit]Breivik prepared a document titled 2083: A European Declaration of Independence.[240] It runs to 1,518 pages and is credited to "Andrew Berwick" (an Anglicization of Breivik's name).[241][242] Breivik admitted in court that it was mostly other people's writings he had copied and pasted from different websites.[243] The file was e-mailed to 1,003 addresses about 90 minutes before the bomb blast in Oslo.[240][244] The document describes two years of preparation of unspecified attacks, supposedly planned for late 2011, involving a rented Volkswagen Crafter van (small enough not to require a truck driving licence) loaded with 1,160 kilograms (2,560 lb) of ammonium nitrate/fuel oil explosive (ANFO), a Ruger Mini-14 semi-automatic rifle, a Glock 34 pistol, personal armour (including a shield), caltrops, and police insignias. It reported Breivik spent thousands of hours gathering email addresses from Facebook for distribution of the document, and that he rented a farm as a cover for a fake farming company buying fertilizer (three tons for producing explosives and three tons of a harmless kind to avoid suspicion) and as a lab. It describes burying a crate with the armour in the woods in July 2010, collecting it on 4 July 2011, and abandoning his plan to replace it with survival gear because he did not have a second pistol. It also expresses support for far-right groups such as the English Defence League[240] and paramilitaries such as the Scorpions in Serbia.[245]

The introductory chapter of the manifesto asserts that political correctness is responsible for social rot. He blames the Frankfurt School for the promulgation of political correctness, which he identifies with "cultural Marxism". Parts of these sections are plagiarized from Political Correctness: A Short History of an Ideology by Paul Weyrich's Free Congress Foundation.[246][247] Major parts of the compendium are attributed to the pseudonymous Norwegian blogger Fjordman, while Serbian writer, Srđa Trifković, is quoted in a number of places.[248][249] The text also copies sections of the Unabomber manifesto, without giving credit, while replacing the words "leftists" with "cultural Marxists" and "black people" with "muslims".[250][251] The New York Times described American influences in the writings, observing that the compendium mentions the anti-Islamist American Robert Spencer 64 times and cites Spencer's works at great length.[252] The work of Bat Ye'or is frequently cited.[253] Conservative blogger Pamela Geller is also mentioned as a source of inspiration.[252] Breivik blames feminism for allowing the erosion of the fabric of European society[31] and advocates a restoration of patriarchy which he claims would save European culture.[31][254]

India, and in particular Hindu nationalism, figures repeatedly in the manifesto where he expresses praise and admiration for Hindu nationalist groups. He claimed to have attempted to reach out to Indians through email and Facebook.[255][256] In his writings Breivik also states that he wants to see European policies on multiculturalism and immigration more similar to those of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan[257] which he said are "not far from cultural conservatism and nationalism at its best".[258] He expressed his admiration for the "monoculturalism" of Japan and for Japan and South Korea's refusal to accept refugees.[259][260] The Jerusalem Post describes his support for Israel as a "far-right Zionism".[261] He calls all "nationalists" to join in the struggle against "cultural Marxists/multiculturalists".[27] He also expressed his admiration of the Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, finding him "a fair and resolute leader worthy of respect", though he was "unsure at this point whether he has the potential to be our best friend or our worst enemy." Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov has denounced Breivik's actions as the "delirium of a madman".[262]

Analysis

[edit]Benjamin R. Teitelbaum, former professor of Nordic Studies (current professor of musicology) at the University of Colorado, argues that several parts of the manifesto suggest that Breivik was concerned about race, not only about Western culture or Christianity, labelling him as a white nationalist.[263]

Thomas Hegghammer of the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment described the ideologies of Breivik as "not fitting the established categories of right-wing ideology, like white supremacism, ultranationalism or Christian fundamentalism", but more akin to pan-nationalism and a "new doctrine of civilisational war".[264] Norwegian social scientist Lars Gule characterised Breivik as a "national conservative, not a Nazi".[265] Pepe Egger of the think-tank Exclusive Analysis says "the bizarre thing is that his ideas, as Islamophobic as they are, are almost mainstream in many European countries".[266]

In one section of the manifesto titled "Battlefield Wikipedia", Breivik explained the importance of using Wikipedia as a venue for disseminating views and information to the general public,[267] although the Norwegian professor Arnulf Hagen claims that this was a document that he had copied from another author and that Breivik was unlikely to be a contributor to Wikipedia.[268] According to the leader of the Norwegian chapter of the Wikimedia Foundation an account belonging to Breivik has been identified.[269] On the second day of his trial, Breivik cited Wikipedia as the main source for his worldview.[270]

Influence

[edit]Breivik's manifesto 2083: A European Declaration of Independence circulated in online fascist forums where strategies were set and tactics debated.[271] Australian terrorist Brenton Harrison Tarrant, who killed 51 people (all Muslims) and injured 50 more during the Christchurch mosque shootings at Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Islamic Centre in Christchurch, New Zealand, mentioned Breivik in his manifesto The Great Replacement as one of the far-right mass murderers and killers he supports. Tarrant said he "only really took true inspiration from Knight Justiciar Breivik" even going as far as to claim "brief contact" with him and his organization Knights' Templar.[272][273] With the exception of the Christchurch shootings, Breivik's influence on the tactics of far-right terrorists appeared to be rather limited.[274]

Beliefs

[edit]Breivik had been active on several anti-Islamic and nationalist blogs, including document.no,[275][276][277] and was a regular reader of Gates of Vienna, the Brussels Journal and Jihad Watch.[278] He cited Jihad Watch 162 times in his 2011 manifesto,[279] and cited Daniel Pipes and the Middle East Forum a further 18 times.[280] Breivik frequently praised the writings of blogger Fjordman.[281] He used Fjordman's thinking to justify his actions, citing him 111 times in the manifesto.[282] In 2016, however, Breivik stated that he had in reality been a "national socialist", or Nazi, since age twelve, read Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf at age fourteen, and that he had in later years only disguised himself as a counter-jihadist.[283] In 2022, he blamed the neo-Nazi organisation Blood & Honour for having radicalised him to the use of violence, and that this group carried the main responsibility for the terror attacks.[284]

After studying several militant groups, including the IRA, ETA and others, Breivik suggests far-right militants should adopt al-Qaeda's methods, learn from their success, and avoid their mistakes.[285][286] Breivik described al-Qaeda as the "most successful revolutionary force in the world" and praised their "cult of martyrdom".[270] He stated that the European Union is a project to create "Eurabia"[287][288][289] and describes the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as being authorised by "criminal western European and American leaders".[290] In his writings, Breivik stated that "the Battle of Vienna in 1683 should be celebrated as the Independence Day for all Western Europeans as it was the beginning of the end for the second Islamic wave of Jihads".[291] The manifesto urges the Hindu nationalists to drive Muslims out of India.[292] It demands the forced deportation of all Muslims from Europe, based on the model of the Beneš decrees.[33][293]

In a letter Breivik sent to international media in 2014, he stated that he had exploited "counterjihadist" rhetoric as a means to protect "ethno-nationalists" and instead start a media hunt against "anti-nationalist counterjihadist"-supporters, in a strategy he calls "double psychology".[168] Breivik further stated that he strives for a "pure Nordic ideal", advocating the establishment of a similar party in Norway to the neo-Nazi Party of the Swedes, and identifying himself as a part of "Western Europe's fascist movement".[168] Moreover, he stated that his "support" for Israel is limited for it to function as a place to deport "disloyal Jews".[168] During the trial in 2012, Breivik listed as his influences a number of neo-Nazi activists, as well as perpetrators of attacks against immigrants and leftists, considering them "heroes".[294][295] In 2019, he claimed to have converted to democratic right-wing populism.[296] This has later been disputed since he still identifies as a "national socialist" and is possibly "more radical" than before with advocacy for white separatism.[297]

Religious views

[edit]On 17 April 2012, when asked by Lawyer Siv Hallgren if he is religious, Breivik answered in the affirmative. Later, during the same conversation, he stated: "I am Christian. I believe in God, but I am a bit religious, but not especially religious."[298] Breivik has later described his religious faith as being Odinism, a neopagan belief.[166][167][299] While Breivik was frequently described in the media as a "Christian fundamentalist",[300][301][302][303][304] such assertions were disputed in a number of sources,[305] and Breivik has later denied it, stating in letters to Norwegian newspaper Dagen that he "is not, and has never been a Christian", and that he thinks there are few things in the world more "pathetic" than "the Jesus-figure and his message".[166] He said he prays and sacrifices to Odin, and identifies his religion as Odinism.[166]

Following his arrest, Breivik was characterised by analysts as being a right-wing extremist with anti-Muslim views and a deep-seated hatred of Islam,[306] who considered himself a knight dedicated to stemming the tide of Muslim immigration into Europe.[307][308] At the same time, Breivik said both during his trial and in his manifesto to have been inspired by jihadist groups, and stated his willingness to work together with groups like Al-Qaeda and Al-Shabaab in order to conduct attacks with weapons of mass destruction against Western targets.[309][310][311]

Links to organizations

[edit]Shooting club

[edit]Breivik was an active member of an Oslo shooting club between 2005 and 2007, and from 2010. According to the club, which banned him for life after the attacks, Breivik took part in thirteen organized training sessions and one competition since June 2010.[312] The club states that it does not evaluate the members' suitability regarding possession of weapons.[313]

Freemasons

[edit]At the time of the attacks, Breivik was a member of the Lodge of St. Olaf at the Three Columns in Oslo[314] and had displayed photographs of himself in partial Masonic regalia on his Facebook profile.[315][316] In interviews after the attacks, his lodge said it had only minimal contact with him, and that when made aware of Breivik's membership, Grand Master of the Norwegian Order of Freemasons, Ivar Skaar, issued an edict immediately excluding him from the fraternity based upon the acts he carried out and the values that appear to have motivated them.[317][318] According to the Lodge records, Breivik took part in a total of four meetings between his initiation in February 2007 and his exclusion from the order (one each to receive the first, second, and third degrees, and one other meeting)[319] and held no offices or functions within the Lodge.[320] Skaar said that although Breivik was a member of the Order, his actions showed that he was in no way a Mason.[319]

Progress Party

[edit]Breivik became a member of the Progress Party (FrP) in 1999. He paid his membership dues for the last time in 2004 and was removed from the membership list in 2006. During his time in the Progress Party, he held two positions in the Progress Party's youth organisation FpU: he was the chair of the local Vest Oslo branch from January to October 2002, and a member of the board of the same branch from October 2002 until November 2004.[321][322][323] After the attack, the Progress Party immediately distanced itself from Breivik's actions and ideas.[324] At a 2013 press conference, Ketil Solvik-Olsen said that Breivik "left us [the party] because we were too liberal".[325]

English Defence League (EDL)

[edit]Breivik claimed he had contact with the far-right English Defence League (EDL), a movement in the United Kingdom that has been accused of Islamophobia. He allegedly had extensive links with senior EDL members[326] and wrote that he attended an EDL demonstration in Bradford.[327] On 26 July 2011, EDL leader Tommy Robinson denounced Breivik and his attacks and has denied any official links with him.[328]

On 31 July 2011, Interpol asked Maltese police to investigate Paul Ray, a former EDL member who blogs under the name "Lionheart". Ray conceded that he may have been an inspiration for Breivik, but deplored his actions.[329][330] In an online discussion on the Norwegian website Document.no on 6 December 2009, Breivik proposed establishing a Norwegian version of the EDL. Breivik saw this as the only way to stop left-wing radical groups like Blitz and SOS Rasisme from "harassing" Norwegian cultural conservatives.[331] Following the establishment of the European Defence League, the Norwegian Defence League (NDL) launched in 2010. Breivik indeed became a member of this organization under the pseudonym "Sigurd Jorsalfar".[332] Former head of the NDL, Lena Andreassen, claimed that Breivik was ejected from the organization when she took over as leader in March 2011 because he was too extreme.[333]

Knights Templar

[edit]In his manifesto and during interrogation, Breivik claimed membership in an "international Christian military order", which he called the new Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Solomonici (PCCTS, Knights Templar). According to Breivik, the order was established as an "anti-Jihad crusader-organisation" that "fights" against "Islamic suppression" in London in April 2002 by nine men: two Englishmen, a Frenchman, a German, a Dutchman, a Greek, a Russian, a Norwegian (apparently Breivik), and a Serb (supposedly the initiator, not present, but represented by Breivik). The compendium gives a "2008 estimate" that there are between 15 and 80 "Justiciar Knights" in Western Europe, and an unknown number of civilian members, and Breivik expects the order to take political and military control of Western Europe.[334]

Breivik gave his own code name in the organisation as Sigurd and that of his assigned "mentor" as Richard, after the twelfth-century crusaders and kings Sigurd Jorsalfar of Norway and Richard the Lionheart of England.[335] He called himself a one-man cell of this organisation and claimed that the group has several other cells in Western countries, including two more in Norway.[101] On 2 August 2011, Breivik offered to provide information about these cells, but on unrealistic preconditions.[336]

After an intense investigation assisted internationally by several security agencies, the Norwegian police did not find any evidence a PCCTS network existed, or that an alleged 2002 London meeting ever took place. The police concluded Breivik's claim was a figment of his imagination because of his schizophrenia diagnosis, and were confident that he had no accessories. Breivik continued to insist he belonged to an order and that his one-man cell was "activated" by another clandestine cell.[337] On 14 August 2012, several Norwegian politicians and media outlets received an email from someone claiming to be Breivik's "deputy", demanding that Breivik be released and making more threats against Norwegian society.[338]

See also

[edit]- List of rampage killers (religious, political, or ethnic crimes)

- Counter-jihad

- Far-right politics

- Hate crime

- Right-wing terrorism

- Spree killer

References

[edit]- ^ "Notat – Redgjørelse Stortinget" (PDF). Politiet. 10 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Slik var Behring Breiviks bevegelser på Utøya". Aftenposten. 16 April 2012. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "En av de sårede døde på sykehuset" [One of the wounded died in hospital]. Østlendingen (in Norwegian). 24 July 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Norwegian killer Breivik changes his name". BBC News. 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Breivik pronouncing his own name". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Bells toll in Norway to mark 10 years since neo-Nazi Breivik killed 77". Reuters. 22 July 2021.

- ^ "Norway extremist makes Nazi salute as he seeks parole just 10 years after killing 77". Times of Israel. 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Anders Breivik: Mass murderer sues Norway over prison isolation". BBC News. 9 January 2024.

A neo-Nazi who killed 77 people in Norway in 2011 is suing the country in a bid to end his years in isolation.

- ^ "Court rejects parole for neo-Nazi mass murderer Breivik". Deutsche Welle. 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Psychiatrist says Breivik is stable and should be out, and as breivik said what he did was a good thing hitting parole chances". France 24. 19 January 2022.

Neo-Nazi Breivik, who killed 77 people in twin attacks, was sentenced in 2012 to 21 years in prison, which can be extended as long as he is considered a threat.

- ^ "Norway's far-right mass killer Breivik sues state over prison isolation". Al Jazeera. 19 August 2023.

A neo-Nazi, Breivik killed 77 people, most of them teenagers, in shootings and a bombing attack in Norway's worst peacetime atrocity in July 2011.

- ^ Sources describing Breivik as neo-Nazi include:[6][7][8][9][10][11]

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie (20 April 2016). "Anders Breivik: Right-wing extremist who killed 77 people in Norway massacre wins part of human rights case". The Independent. London, England. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Mark; Cowell, Alan (24 August 2012). "Norway Killer Is Ruled Sane and Given 21 Years in Prison". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Pracon, Adrian (1 June 2012). "Utøya, a survivor's story: 'No!' I yelled. 'Don't shoot!'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Rettssaken – Aktoratets prosedyre" [The trial – The defense counsel's closing] (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 June 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ The verdict convicts Breivik for violations of the criminal code §147 (terrorism), §148 (fatal explosion), and §233 (murder).

- ^ "Mass killer Anders Breivik sentencing – live text coverage". RAPSI. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "En modig dom". 24 August 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Meldalen, Sindre Granly; Brustad, Line; Kristiansen, Arnhild Aass; Sandli, Hansen; Espen Frode; Krokfjord, Torgeir P. (2 April 2012). "Breivik planla tagging som militær operasjon" [Breivik planned tagging as military operation]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Father of Norway attack suspect says in shock". Reuters. 24 July 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ [1]. Retrieved 11 April 2021. "Oslo pistolklubb bekrefter at Anders Behring Breivik har vært medlem av klubben fra 2005 til 2007 og siden juni 2010, opplyser pistolklubben i en pressemelding."

- ^ a b "Terrorsiktede Anders Behring Breivik tappet selskapet like før det gikk konkurs". Hegnar.no. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d using a July 2011 conversion rate

- ^ a b c d e f Sujay Dutt. "Breivik lade alla besparingar på terrorattentaten" (in Swedish). DN.se. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, Matthew (25 July 2011). "Norway gunman claims he had a nine-year plan to finance attacks". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b Ben Hartman (24 July 2011). "Norway attack suspect had anti-Muslim, pro-Israel views". Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ Kumano-Ensby, Anne Linn (23 July 2011). "Sendte ut ideologisk bokmanus en time før bomben". NRK News (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Avkristina Overnight. "Var aktiv i norsk antiislamsk organisasjon – Nyheter – Innenriks". Aftenposten.no. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Bjoern Amland; Sarah Dilorenzo (24 July 2011). "Lawyer: Norway suspect wanted a revolution". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Jones, Jane Clare (27 July 2011). "Anders Breivik's chilling anti-feminism". The Guardian.

- ^ Goldberg, Michelle (24 July 2011). "Norway Killer's Hatred of Women". The Daily Beast.

- ^ a b Buehrer, Jack (27 July 2011). "Oslo terrorist sought guns in Prague". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015.

- ^ McIntyre, Jody. "Anders Behring Breivik: a disturbing ideology". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ "Norway Shooting Suspect Breivik Is Ordered Into Isolation for Four Weeks". Bloomberg L.P. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Olsen, Ole N.; Andresen, David (29 November 2011). "Rettspsykiaterne beskriver bisarre vrangforestillinger hos Breivik". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Norway killer Breivik is 'not psychotic', say experts". BBC News. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Norway's mass killer Breivik 'declared sane'". BBC News. 10 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ a b Lewis, Mark and Cowell, Alan (16 April 2012). "Norwegian Man Claims Self-Defense in Killings". The New York Times. New York City.

- ^ "Breivik vant over staten i saken om soningsforholdene". aftenbladet.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). 20 April 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ https://www.nrk.no/nyheter/. NRK.no. Retrieved 2024-12-09

- ^ Ighoubah, Farid (11 July 2024). "Staten sparer millionbeløp – derfor får ikke Anders Behring Breivik viljen sin". Nettavisen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ NRK (19 October 2023). "Aftenposten: Datoen klar for Breiviks neste rettsrunde". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Norway court says mass killer Breivik's prison isolation not 'inhumane'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ a b Solheim, Eric Kjerstad (27 May 2024). "Aftenposten: Anders Behring Breivik får ny rettssak". VG (in Norwegian). Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Rayment, Sean (25 July 2011). "Modest boy who became a mass murderer". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Allen, Peter (23 July 2011). "Norway Killer: Father horrified by Anders Behring Breivik killing spree". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Åsebø, Synnøve (9 June 2017). "Anders Behring Breivik har skiftet navn". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Allen, Peter; Fagge, Nick; Cohen, Tamara (25 July 2011). "Mummy's boy who lurched to the Right was 'privileged' son of diplomat but despised his liberal family". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Skårderud, Finn (26 April 2012). "Psykiater Finn Skårderud: – Ekstremt viktig å forstå mer av Breivik" [Psychiatrist Finn Skårderud: – Extremely important to understand more of Breivik]. Dagbladet (Interview) (in Norwegian). Interviewed by Møystad, Cathrine Loraas. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Orange, Richard (7 October 2012). "Anders Behring Breivik's mother 'sexualised' him when he was four". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ – Breivik var skadet allerede som toåring. Retrieved 9 April 2021. "Psykologen ved Statens Senter for Barne – og Ungdomspsykiatri (SSBU), som på 80-tallet observerte samspillet mellom Anders og hans mor, ble avhørt av politiet etter terroraksjonen 22.juli 2011."

- ^ a b c d e f g Olsen, Asbjørn (20 April 2016). "Breivik was 'already damaged by the age of two'". TV2. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d AS, TV 2 (16 March 2016). "Breivik var skadet allerede som toåring". Tv2.no. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ – Breivik var skadet allerede som toåring. Retrieved 9 April 2021. " 'Han så bare jentetisser', fortalte hun dem."

- ^ "- Breivik var skadet allerede som toåring". 17 March 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Kim Willsher (25 July 2011). "Norway gunman's father speaks out: 'He should have taken his own life'". the Guardian. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "En av treningskameratene på ungdomsskolen var jo fra Midtøsten". Norge – NRK Nyheter. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Bundgaard, Maria (23 July 2011). "Skolekammerat: Han hjalp mobbeofre".

- ^ Willsher, Kim (26 July 2011). "Norway gunman's father speaks out: 'He should have taken his own life'". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

Within a year of the boy's birth, in February 1979, the couple had split. Jens Breivik remained in London and Behring moved back to Oslo with Anders and his elder half-sister.

- ^ Gibson, David (28 July 2011). "Is Anders Breivik a 'Christian' terrorist?". Times Union. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ Sadhbh, Walshe (28 July 2011). "The Right Word: Telling left from right". The Guardian (UK). London.

- ^ "Norway suspect admits responsibility". Sky News. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "Slik var dramaet på Utøya". Verdens Gang. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Anders Behring Breivik's father: 'My son should have taken his own life'". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Henley, Jon (13 April 2012). "Anders Behring Breivik trial: the father's story". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

Breivik disputes this. "It's true I was angry," he says. "Several times the police called me to say he had sprayed buildings, trains, and buses. He was also shoplifting. But I was always willing to see him, and he knew that. It was Anders who cut it off. His decision, not mine.

- ^ "1995: Året da alt forandret seg – nyheter". Dagbladet.no. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Skrøt av egen briljans, utseende, kjærester og penger – nyheter". Dagbladet.no. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Aune, Oddvin. "32-åringen skal tilhøre høyreekstremt miljø". NRK. No. special. Oslo.

Etter det NRK får opplyst, har ikke den pågrepne noen yrkesmilitær bakgrunn. Han ble fritatt fra verneplikt, og dermed har han ikke spesialutdanning eller utenlandsoppdrag for Forsvaret." – "From what NRK have been informed, the suspect has no military background. He was exempt from conscription and therefore does not have military training or service abroad.

- ^ Landsend, Merete (27 July 2011). "Skrøt av egen briljans, utsende, kjærester og penger". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Oslo. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

Kilder i Forsvarets sikkerhetsavdeling Dagbladet har snakket med, forteller at Breivik allerede ved sesjon ble luket ut av rullene som ikke tjenesteskikket." – "Sources in the Defence Security Department that Dagbladet has talked to, says Breivik was weeded out from the files as unfit for service during the service assessment.

- ^ Hansen, Anette Holth; Skille, Øyvind Bye (23 July 2011). "Han var en utmerket kollega" (in Norwegian). NO: NRK.

- ^ "Passet avslørte Breiviks verdensturne". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 3 February 2012.

- ^ Lankevich, Denis (28 July 2011). Он был типичным североевропейским туристом. Gazeta.ru (in Russian).

- ^ "Breivik var på konejakt i Hviterussland" (in Norwegian). Norway: NRK.no. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ "Politiet etterforsker terroristen i minst 16 land". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 5 January 2012.

- ^ "Anders Behring Breivik: Mum is the only one who can make me emotionally unstable". Nettavisen. 30 November 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Brønnøysundregistrene – Nøkkelopplysninger fra Enhetsregisteret". Brønnøysund Business Register (in Norwegian). NO: Ministry of Trade and Industry. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ "Profile: Norway attacks suspect Anders Behring Breivik". BBC. 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Oslo killer sought weapons from Prague's underworld". Czech Position. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Skytternes taushet". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ "Der Terrorist und die Brandstifter". Der Spiegel 1 August 2011

- ^ a b "Pågrepet 32-åring kalte seg selv nasjonalistisk". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.[verification needed]

- ^ "Oslo bomb suspect bought 6 tonnes fertiliser: supplier". Reuters. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Eksplosjonen i Oslo sentrum 22. juli 2011" [The explosion in Oslo 22 July 2011] (in Norwegian). 23 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ "Her er restene av bombebilen" [Here is the remains of the car]. NRK (in Norwegian). 29 October 2011.

- ^ "Ble sett av ti kameraer" [Was seen by ten surveillance cameras]. ABC Nyheter (in Norwegian). 16 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011.

- ^ "Dette er Breivik tiltalt for" [Breivik's indictment] (in Norwegian). NRK. 7 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Oslo government district bombing and Utøya island shooting July 22, 2011: The immediate prehospital emergency medical service response". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 26 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Læring for bedre beredskap; Helseinnsatsen etter terrorhendelsene 22. juli 2011" (in Norwegian). 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ "Slik skaffet han politiuniformen" [How he obtained the uniform]. NRK (in Norwegian). 24 July 2011.

- ^ "Slik var Behring Breivik kledd for å drepe" [How Behring Breivik was dressed to kill]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 20 November 2011.

- ^ "Terrorofrene på Utøya og i Oslo". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Schibsted ASA. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Navn på alle terrorofre offentliggjort". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Schibsted ASA. 29 July 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Sanchez, Raf (25 July 2011). "Norway killings: Princess's brother Trond Berntsen among dead". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Helen Pidd; James Meikle (27 July 2011). "Anders Behring Breivik: 'It was a normal arrest'". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Arbeiderpartiet har sveket landet og prisen fikk de betale fredag" (in Norwegian). Nrk.no. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Grivi, Jarle Brenna et al. "I'm the greatest monster since Quisling: This said Breivik under interrogation at Utøya", Verdens Gang, 2 January 2012. (accessed 18 November 2015).

- ^ a b "Ruling on holding Anders Behring Breivik in custody (Norwegian)" (PDF). Oslo District Court. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "First Court Hearing for Anders Behring Breivik Held in Private". International Business Times. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Norway massacre suspect appears to be insane, his lawyer says". Haaretz. Reuters. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Steven Erlanger; Alan Cowell (25 July 2011). "Norway suspect hints that he did not act alone". The New York Times.

- ^ "Ruling on holding Anders Behring Breivik in extended custody (Norwegian)" (PDF). Oslo District Court. 14 November 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Sladder ikke tiltalen". Avisa Nordland (in Norwegian). ANB-NTB. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Ankesak om 22. juli kan begynne i januar 2013" [Appeal case about 22 July can start in January 2013] (in Norwegian). NRK. NTB. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Johnsen, Alf Bjarne; Sæther, Anne Stine; Andersen, Gordon (24 January 2012). "Breivik kan få eget sykehus på Ila" [Breivik may get his own hospital at Ila]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "23-årig amerikan vill träffa Breivik" [23-year-old American wants to meet Breivik]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 19 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Moland, Annemarte; Andersen, Ingunn; Omland, Ellen; Skille, Øyvind Bye (22 February 2012). "– Breivik brevveksler med meningsfeller" [Breivik exchanging letters with like-minded people] (in Norwegian). NRK. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Breivik har sagt ja til intervju igjen" [Breivik has agreed to another interview]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). NTB. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b Torgeir Huseby; Synne Sørheim (29 November 2011). "Forensic psychiatric statement Breivik, Anders Behring" (PDF) (in Norwegian). TV2. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Norway massacre: Breivik declared insane". BBC. 29 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Breivik sees opportunities". The Foreigner. 1 December 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Norway split on Breivik's likely fate in mental ward, as mass-killer himself 'insulted' by ruling". Agence France-Presse. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Norway killer Anders Behring Breivik 'is not psychotic'". The Daily Telegraph. London. 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Den rettsmedisinske kommisjon; Andreas Hamnes; Agneta Nilsson; Gunnar Johannessen; Jannike E. Snoek; Kirsten Rasmussen; Knut Waterloo; Karl Heinrik Melle (20 December 2011). "Breivek, Anders Behring. Rettspsykiatrisk erklæring" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo Tingrett. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Ravndal, Dennis; Jarle Brenna; Fridtjof Nygaard; Marianne Vikås; Morten Hopperstad (6 January 2012). "Breivik not likely to bluff about mental illness". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Svein Holden; Inga Bejer Engh (4 January 2012). "Anders Behring Breivik – the question of appointing new forensic psychiatrists" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo Statsadvokatembeter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Spiegel Magazine Court Orders New Psychiatric Review for Breivik

- ^ "Families question experts on Oslo terrorist". Agence France-Presse. 5 January 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ Liss Goril Anda (25 November 2011). "Norway massacre: Breivik declared insane". BBC News. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Regular Criminal Code (Norwegian: straffeloven)" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. 22 May 1909. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Breivik may avoid prison". Sky News Australia. 3 March 2012. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Anders Behring Breivik: prosecutor may accept he's not responsible for killings". The Province. Vancouver, Canada. AFP. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Mark (22 June 2012). "Breivik delivers final tirade". the Guardian. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Norway Mass Killer Gets the Maximum: 21 Years". The New York Times. 25 August 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Diagnosis of insanity would be 'worse than death,' Norway killer says". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Reuters. 4 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Psykiater mener Breivik har Aspergers og Tourettes Archived 13 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Vårt Land

- ^ "Dette er diagnosene på Breivik – nyheter". Dagbladet.no. 9 June 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Orange, Richard (11 June 2012). "Anders Behring Breivik is lying, not delusional". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Lars Bevanger (14 June 2012). "Breivik trial: Psychiatric reports scrutinised". BBC News Europe. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Total mangel på respekt". 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ Professor Douglas, Linder. "Breivik Trial: Verdict and Sentence". Famous Trials by Professor Douglas O. Linder. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Anders Behring Breivik: Norway court rules him sane". BBC News. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Lippestad: – Breivik bekrefter at han ikke anker". TV 2. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Andreas Bakke Foss (31 January 2014). "Nå er dommen mot Breivik rettskraftig". Aftenposten.no. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Breivik: Jeg anker ikke". NRK. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Telemark fengsel, Skien avdelingo". Kriminalomsorgen.no. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dom" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Breivik-saken forklart" [The Breivik Trial explained]. Dagbladet.no. 23 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.