Maned sloth

| Maned sloth[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | Bradypodidae |

| Genus: | Bradypus |

| Species: | B. torquatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bradypus torquatus Illiger, 1811

| |

| |

| Maned sloth range | |

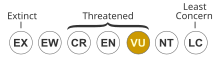

The maned sloth (Bradypus torquatus) is a three-toed sloth that is native to South America. It is one of four species of three-toed sloths belonging to the suborder Xenarthra and are placental mammals. They are endemic to the Atlantic coastal rainforest of southeastern and northeastern Brazil, located in the states of Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and Bahia. Each of the individuals within the species are genetically distinct with different genetic makeup.The maned sloth is listed under Vulnerable (VU) according to the IUCN Red List and have a decreasing population trend.[2]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The maned sloth is found only in the Atlantic coastal rainforest of southeastern and northeastern Brazil.[3][4][5] The sloths are an endemic species unique to Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and Bahia. The largest number of individuals that inhabit the same space within the species currently occupy the state of Bahia. Bahia is also the location for the largest number of genetically diverse maned sloths. However, there is a gap that is created naturally by a valley located in between the rainforests of the states of Bahia and Espírito Santo.[5][6] This makes some of the regions in which Bradypus torquatus occupies extraordinarily isolated which causes a lot of inbreeding, affecting the genetic diversity of the species in other areas. Individual maned sloths have reported to travel over a home range of 0.5 to 6 hectares (1.2 to 14.8 acres), with estimated population densities of 0.1 to 1.25 per hectare (0.04 to 0.51/acre).

The maned sloth is typically found in wet tropical forests with very hot and humid climates that have a very minimal dry season with an annual rainfall of at least 1,200 mm (47.2 in). In the Atlantic coastal rainforest, the wet season is from October to April while the dry season is from may to September. Bradypus torquatus are generally spotted in predominantly evergreen forests, although, with their ability to eat a wide range of leaves, they can also inhabit semi-deciduous and secondary forests. Bradypus torquatus actually chose their habitat carefully. They tend to occupy more shaded areas with larger trees and avoid areas that are more out in the open.[7] Many parts of the forest that maned sloths inhabit have been affected by anthropogenic deforestation and their habitat has been reduced down to 7% of the range of the original biome. It is the main threat to their existence.

Anatomy and morphology

[edit]Maned sloths have a pale brown to gray pelage. Long outer hair covers a short, dense, black and white underfur. The coarse outer coat is usually inhabited by algae, mites, ticks, beetles, and moths. The maned sloth's small head features fur-covered pinnae and anterior oriented eyes that are usually covered by a mask of black hair. The sides of the maned sloth's face and neck feature long hair covering the short hair of the sloth's snout. Facial vibrissae on the maned sloth are sparse.[8] The maned sloth earns its name from a mane of black hair running down its neck and over its shoulders.[3] The mane is usually larger and darker in males than in females, and in the latter, may be reduced to a pair of long tufts. Other than the mane, the fur is relatively uniform in color. Unlike the other three fingered sloths in the Bradypus genus however, they lack a speculum, the patch of bright fur found on the back of a sloth, and do not have black around their eyes resembling a mask.[9] Adult males have a total head-body length of 55–72 centimetres (22–28 in), with a tail about 5 centimetres (2.0 in) long and a weight of 4.0–7.5 kilograms (8.8–16.5 lb). Females are generally larger, measuring 55–75 centimetres (22–30 in), and weighing 4.5–10.1 kilograms (9.9–22.3 lb).[10] Like all other sloths, the maned sloth has very little muscle mass in comparison to other mammals its size. This reduced muscle mass allows it to hang from thin branches.

Ecology and behavior

[edit]General

[edit]Maned sloths are solitary diurnal animals, spending up to 60% to 80% of their day asleep, with the rest more or less equally divided between feeding and traveling.[11] Sloths sleep in crotches of trees or by dangling from branches by their legs and tucking their head in between their forelegs.[12]

Maned sloths rarely descend from the trees because, when on a level surface, they are unable to stand and walk, only being able to drag themselves along with their front legs and claws. They travel to the ground only to defecate or to move between trees when they cannot do so through the branches. The sloth's main defenses are to stay still and to lash out with its formidable claws. However the sloths are good in the water and can swim well.[13]

Diet

[edit]Maned sloths are folivores, and feed exclusively on tree leaves. Overall their diet is broad but they do prefer younger leaves and some plants are consumed more than others. They have many adaptations morphologically, physiologically as well as behaviorally to feed on leaves from trees. These leaves contain very little protein and basic carbohydrates, resulting in an extremely low energy diet. Their diet and their small body size combined make their food pass through their bodies at a very slow rate. Cecropia is one of the main plants consumed by the three toed sloth genus, Bradypus, however in the case of the maned sloth it is not. In fact eating mostly Cecropia as their diet can lead to death in a lot of the individuals.[14]

Reproduction

[edit]Some reports indicate that maned sloths are able to breed year round,[15] but in most cases, reproduction of maned sloths is seasonal. Mating normally takes place between the months of August through October. This period of time is referred to as the late dry season, August and September, and the beginning of the wet or rainy season, October. The wet and hotter season of the year is better for pregnant mothers and infant sloths because of their slow metabolism and their inability to control their body temperature. On the other hand, sloths are born mostly between the months of February to April, which is the early part of the dry season, April and the end of the rainy season, February and March.[16] The period of time between pregnancies, or the inter-birth interval of a female maned sloth is one year.The mother gives birth to a single young, which initially weighs around 300 grams (11 oz) and lacks the distinctive mane found on adults. The young begin to take solid food at two weeks, and are fully weaned by two to four months of age.[17] The young leave the mother at between nine and eleven months of age. Although their lifespan has not been studied in detail, they have been reported to live for at least twelve years. The average age of sexual maturity is around two–three years old[17]

Conservation

[edit]Threats

[edit]The Maned three-toed sloth is considered the most endangered of all of the sloth species and they are listed under the Vulnerable (VU) category according to the IUCN Red List.[2] Due to hunting and anthropogenic deforestation consistently occurring, the sloth species was reduced to about 7% of their original habit in the Atlantic Forest. The major threat to the maned sloth is the loss of its forest habitat as a result of lumber extraction, charcoal production, and clearance for plantations and cattle pastures. This factor along with frequent exposure to various foreign diseases, hunters, and predators contributed to the Maned Three-Toed Sloth's Vulnerable (VU) status in the wild. Continued destruction of habitat could lead to more harmful effects on the species such as a more restrictive diet and a further lack of genetic diversity due to inbreeding.

Efforts

[edit]In 1955, the maned sloth occurred only in Bahia, Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro in eastern Brazil, in the Bahia coastal forests. It has declined since then as these forests have dwindled. There are many sloths being protected in areas such as the Una Biological Reserve, Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve, Poco das Antas Biological Reserve, as well as a few others. There is a recovery plan in action for mammals living in the Central Atlantic Forest in which the sloths are included. There are also organizations such as the Sloth Conservation Foundation whose goal is to protect all species of sloths with fieldwork and working towards conservation.

Prior to 2008, the maned sloth was listed as Endangered (EN) by the IUCN Red List due to the restricted range of land the species occupied, also known as its extent of occurrence (EOO). New data based on studies of the maned sloth's range and locations suggested that the extent of occurrence (EOO) was larger than what had been previously understood. This led to the maned sloth getting down listed from Endangered (EN) to Vulnerable (VU) the following year in 2009.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Gardner, A. (2005). "Bradypus torquatus". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d Chiarello, A.; Moraes-Barros, N. (2014). "Bradypus torquatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T3036A47436575. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T3036A47436575.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b ZSL Living Conservation (2010). "Maned three-toed sloth (Bradypus torquatus)". Evolutionary Distinct & Globally Endangered. ZSL Living Conservation. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

This species is named after its long mane of black hair

- ^ World Land Trust (2010). "Maned Three-toed Sloth Bradypus torquatus". World Land Trust. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

The Maned Three-toed Sloth, also known as the Maned Sloth is the rarest of the sloth species and is endemic to Brazil

- ^ a b Schetino, Marco A. A.; Coimbra, Raphael T. F.; Santos, Fabrício R. (1 July 2017). "Time scaled phylogeography and demography of Bradypus torquatus (Pilosa: Bradypodidae)". Global Ecology and Conservation. 11: 224–235. Bibcode:2017GEcoC..11..224S. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2017.07.002. ISSN 2351-9894.

- ^ Hirsch, André; Chiarello, Adriano Garcia (2012). "The endangered maned sloth Bradypus torquatus of the Brazilian Atlantic forest: a review and update of geographical distribution and habitat preferences: Bradypus torquatus distribution". Mammal Review. 42 (1): 35–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00188.x.

- ^ Falconi, Nereyda; Vieira, Emerson M.; Baumgarten, Julio; Faria, Deborah; Fernandez Giné, Gastón Andrés (1 September 2015). "The home range and multi-scale habitat selection of the threatened maned three-toed sloth (Bradypus torquatus)". Mammalian Biology. 80 (5): 431–439. Bibcode:2015MamBi..80..431F. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2015.01.009. ISSN 1616-5047.

- ^ Gardner, Alfred (2008). Mammals of South America: Marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-226-28242-8. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Searching for the Elusive Maned Sloths of Brazil - SloCo". The Sloth Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Hayssen, V. (2009). "Bradypus torquatus (Pilosa: Bradypodidae)". Mammalian Species. 829: 1–5. doi:10.1644/829.1.

- ^ Chiarello, Adriano G. (September 1998a). "Activity budgets and ranging patterns of the Atlantic forest maned sloth". Journal of Zoology. 246 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00126.x.

- ^ Stewart, Melissa (2004). "At the Zoo: Slow and Steady Sloths". Zoogoer. Friends of the National Zoo. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Maned Three-Toed Sloth: The Animal Files". www.theanimalfiles.com. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Giné, Gastón Andrés Fernandez; Mureb, Laila Santim; Cassano, Camila Righetto (2022). "Feeding ecology of the maned sloth ( Bradypus torquatus ): Understanding diet composition and preferences, and prospects for future studies". Austral Ecology. 47 (5): 1124–1135. Bibcode:2022AusEc..47.1124G. doi:10.1111/aec.13204. ISSN 1442-9985. S2CID 249555234.

- ^ Pinder, L. (1993). "Body measurements, karyotype, and birth frequencies of maned sloth (Bradypus torquatus)". Mammalia. 57 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1515/mamm.1993.57.1.43. S2CID 84663329.

- ^ Dias, Bernardo B.; Dias dos Santos, Luis Alberto; Lara-Ruiz, Paula; Cassano, Camila Righetto; Pinder, Laurenz; Chiarello, Adriano G. (1 January 2009). "First observation on mating and reproductive seasonality in maned sloths Bradypus torquatus (Pilosa: Bradypodidae)". Journal of Ethology. 27 (1): 97–103. doi:10.1007/s10164-008-0089-9. ISSN 1439-5444. S2CID 9320097.

- ^ a b Lara-Ruiz, P. & Chiarello, A.G. (2005). "Life-history traits and sexual dimorphism of the Atlantic forest maned sloth Bradypus torquatus (Xenarthra: Bradypodidae)". Journal of Zoology. 267 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1017/S0952836905007259.