Braddock Expedition

| Braddock Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French and Indian War | |||||||

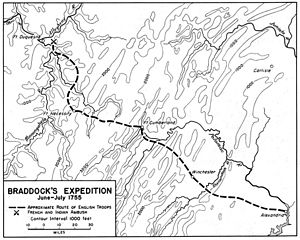

Route of the Braddock Expedition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Native Americans | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

637 natives, 108 French marines 146 Canadian militia[1] |

2,100 regular and provincials 10 cannon[1][2][3][need quotation to verify] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

30 killed 57 wounded[1] |

500+ killed[1] 450+ wounded[4] | ||||||

| Designated | November 3, 1961[5] | ||||||

The Braddock Expedition, also known as Braddock's Campaign or Braddock's Defeat, was a British military expedition which attempted to capture Fort Duquesne from the French in 1755 during the French and Indian War. The expedition, named after its commander General Edward Braddock, was defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9 and forced to retreat; Braddock was killed in action along with more than 500 of his troops. It ultimately proved to be a major setback for the British in the early stages of the war, one of the most disastrous defeats suffered by British forces in the 18th century.[6]

Background

[edit]Braddock's expedition was part of a massive British offensive against the French in North America that summer. As commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Edward Braddock led the main thrust against the Ohio Country with a column some 2,100 strong. His command consisted of two regular line regiments, the 44th and 48th, in all 1,400 regular soldiers and 700 provincial troops from several of the Thirteen Colonies, and artillery and other support troops. With these men, Braddock expected to seize Fort Duquesne easily, and then push on to capture a series of French forts, eventually reaching Fort Niagara. George Washington, promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel of the Virginia Regiment on June 4, 1754, by Governor Robert Dinwiddie,[7] was then just 23, knew the territory and served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to General Braddock.[8] Braddock's Chief of Scouts was Lieutenant John Fraser of the Virginia Regiment. Fraser owned land at Turtle Creek, had been at Fort Necessity, and had served as Second-in-Command at Fort Prince George (replaced by Fort Duquesne by the French), at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers.

Braddock mostly failed in his attempts to recruit Native American allies from those tribes not yet allied with the French; he had but eight Mingo Indians with him led by George Croghan, serving as scouts. A number of Native Americans in the area, notably Delaware leader Shingas, remained neutral. Caught between two powerful European empires at war, the local Native Americans could not afford to be on the side of the loser. They would decide based on Braddock's success or failure.

Braddock's Road

[edit]

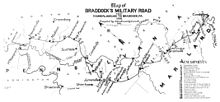

Setting out from Fort Cumberland in Maryland on May 29, 1755, the expedition faced an enormous logistical challenge: moving a large body of men with equipment, provisions, and (most importantly, for attacking the forts) heavy cannons, across the densely wooded Allegheny Mountains and into western Pennsylvania, a journey of about 110 miles (180 km). Braddock had received important assistance from Benjamin Franklin, who helped procure wagons and supplies for the expedition. Among the wagoners were two young men who would later become legends of American history: Daniel Boone and Daniel Morgan. Other members of the expedition included Ensign William Crawford and Charles Scott. Among the officers of the expedition were Thomas Gage, Charles Lee, future American president George Washington, and Horatio Gates.

The expedition progressed slowly because Braddock considered making a road to Fort Duquesne a priority in order to effectively supply the position he expected to capture and hold at the Forks of the Ohio, and because of a shortage of healthy draft animals. In some cases, the column was only able to progress at a rate of two miles (about 3 km) a day, creating Braddock's Road — an important legacy of the march — as they went. To speed up movement, Braddock split his men into a "flying column" of about 1,300 men which he commanded, and, lagging far behind, a supply column of 800 men with most of the baggage, commanded by Colonel Thomas Dunbar. They passed the ruins of Fort Necessity along the way, where the French and Canadians had defeated Washington the previous summer. Small French and Native American war bands skirmished with Braddock's men during the march.

Meanwhile, at Fort Duquesne, the French garrison consisted of only about 250 French marines and Canadian militia, with about 640 Native American allies camped outside the fort. The Native Americans were from a variety of tribes long associated with the French, including Ottawas, Ojibwas, and Potawatomis. Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur, the Canadian commander, received reports from Native American scouting parties that the British were on their way to besiege the fort. He realised he could not withstand Braddock's cannon, and decided to launch a preemptive strike, an ambush of Braddock's army as he crossed the Monongahela River. The Native American allies were initially reluctant to attack such a large British force, but the French field commander Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu, who dressed himself in full war regalia complete with war paint, convinced them to follow his lead.

Battle of the Monongahela

[edit]

By July 8, 1755, the Braddock force was on the land owned by the Chief Scout, Lieutenant John Fraser. That evening, the Native Americans sent delegates to the British to request a conference. Braddock chose Washington and Fraser as his emissaries. The Native Americans asked the British to halt their advance, claiming that the French could be persuaded to peacefully leave Fort Duquesne. Both Washington and Fraser recommended that Braddock approve the plan, but he demurred.

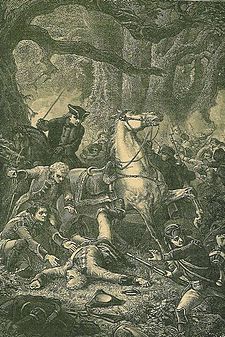

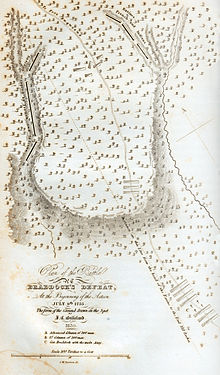

On July 9, 1755, Braddock's men crossed the Monongahela without opposition, about 10 miles (16 km) south of Fort Duquesne. The advance guard of 300 grenadiers and colonials, accompanied by two cannon, and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage began to move ahead. Washington tried to warn Braddock of the flaws in his plan — such as pointing out that the French and the Native Americans fought differently than the open-field style used by the British -- but his efforts were ignored: Braddock insisted that his troops fight as "gentlemen". Then, unexpectedly, Gage's advance guard came upon Beaujeu's party of French and Native Americans, who were hurrying to the river, behind schedule and too late to prepare an ambush.

In the skirmish that followed between Gage's soldiers and the French, Beaujeu was among those killed by the first volley of musket fire by the grenadiers. Although some 100 French Canadians fled back to the fort and the noise of the cannon held the Native Americans off, Beaujeu's death did not have a negative effect on French morale. Jean-Daniel Dumas, a French officer, rallied the rest of the French and their Native American allies. The battle, known as the Battle of the Monongahela, or the Battle of the Wilderness, or just Braddock's Defeat, was officially begun. Braddock's force was approximately 1,400 men. The British faced a French and Native American force estimated to number between 300 and 900. The battle, frequently described as an ambush, was actually a meeting engagement, where two forces clash at an unexpected time and place. The quick and effective response of the French and Native Americans — despite the early loss of their commander — led many of Braddock's men to believe they had been ambushed. However, French battle reports state that while an ambush had been planned, the sudden arrival of the British forced a direct confrontation.

After an exchange of fire, Gage's advance group fell back. In the narrow confines of the road, they collided with the main body of Braddock's force, which had advanced rapidly when the shots were heard. The entire column dissolved in disorder as the Canadian militiamen and Native Americans enveloped them and began firing from the dense woods on both sides. At this time, the French marines began advancing from the road and blocked any attempt by the British to move forward.

Following Braddock's example, the officers kept trying to form their men into standard battle lines so they could fire in formation - a strategy that did little but make the soldiers easy targets. The artillery teams tried to provide covering fire, but there was no space to load the pieces properly and the artillerymen had no protection from enemy sharpshooters. The provincial troops accompanying the British eventually broke ranks and ran into the woods to engage the French; confused by what they thought were enemy reinforcements, panicking British regulars started mistakenly firing on the provincials. After several hours of intense combat, Braddock was fatally shot off his horse, and effective resistance collapsed. Washington, although he had no official position in the chain of command, was able to impose and maintain some order. He formed a rear guard, which allowed the remnants of the force to disengage. This earned him the sobriquet Hero of the Monongahela, by which he was toasted, and established his fame for some time to come.

We marched to that place, without any considerable loss, having only now and then a straggler picked up by the French and scouting Indians. When we came there, we were attacked by a party of French and Indians, whose number, I am persuaded, did not exceed three hundred men; while ours consisted of about one thousand three hundred well-armed troops, chiefly regular soldiers, who were struck with such a panic that they behaved with more cowardice than it is possible to conceive. The officers behaved gallantly, in order to encourage their men, for which they suffered greatly, there being near sixty killed and wounded; a large proportion of the number we had.

— George Washington, July 18, 1755, letter to his mother.[9]

By sunset, the surviving British forces were retreating back down the road they had built. Braddock died of his wounds during the long retreat, on July 13, and is buried within the Fort Necessity parklands. Of the approximately 1,300 men Braddock had led into battle, 456 were killed and 422 wounded. Commissioned officers were prime targets and suffered greatly: out of 86 officers, 26 were killed and 37 wounded. Of the 50 or so women that accompanied the British column as maids and cooks, only 4 survived. The French and Canadians reported 8 killed and 4 wounded; their Native American allies lost 15 killed and 12 wounded.

Colonel Dunbar, with the reserves and rear supply units, took command when the survivors reached his position. He ordered that excess supplies and cannons should be destroyed before withdrawing, burning about 150 wagons on the spot. Ironically, at this point the defeated, demoralized and disorganised British forces still outnumbered their opponents. The French and Native Americans did not pursue; they were far too busy looting dead bodies and collecting scalps. The French commander, Dumas, realized Braddock's army was utterly defeated. Yet, to avoid upsetting his men, he did not attempt any further pursuit.

Strength of the expedition

[edit]According to returns given June 8, 1755, at the encampment at Will's Creek.

- His Majesty's Troops

| Regiment | Officers present | Staff present | Sergeants present | Drummers and effectives present | Wanting to complete the establishment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44th Foot | 33 | 5 | 30 | 790 | 280 |

| 48th Foot | 34 | 5 | 30 | 704 | 366 |

| Capt. John Rutherford's Independent Company, New York | 4 | 1 | 3 | 93 | – |

| Capt. Horatio Gates's Independent Company, New York | 4 | 1 | 3 | 93 | – |

| Detachment from South Carolina, commanded by Capt. Paul Demeré | 4 | 0 | 4 | 102 | – |

| Source:[10] |

Detachement under Capt. Robert Hind

| Military branch present | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Officers | Surgeon | Sergeants | Corporals and Bombardiers | Gunners | Matrosses | Drummer | Total |

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 32 | 1 | 70 |

| Civil branch present | |||||||

| Wagon master | Master of Horse | Commissary | Assistant Commissary | Conductors | Artificers | N/A | Total |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 12 | n/a | 22 |

| Source:[10] | |||||||

| Troop or Company | Officers present | Staff present | Sergeants present | Drummers and effectives present | Wanting to complete the establishment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capt. Robert Stewart's Virginia Light Horse | 3 | 0 | 2 | 33 | – |

| Capt. George Mercer's Virginia Artificers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 42 | 11 |

| Capt. William Polson's Virginia Artificers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 50 | 3 |

| Capt. Adam Stevens's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 3 | 3 | 53 | – |

| Capt. Peter Hogg's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 42 | 11 |

| Capt. Thomas Waggoner's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 53 | – |

| Capt. Thomas Cocke's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 47 | 6 |

| Capt. William Perronée's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 52 | 1 |

| Capt. John Dagworthy's Maryland Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 53 | – |

| Capt. Edward Brice Dobb's North Carolina Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 72 | 28 |

| Source:[10] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Borneman, Walter R. (2007). The French and Indian War. Rutgers. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-06-076185-1.

French: 28 killed 28 wounded, Indian: 11 killed 29 wounded

- ^ History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Duncan, Major Francis, London, 1879, Vol. 1, p. 58, Fifty Royal Artillerymen, 4 brass 12 pounders, 6 brass 6 pounders, 21 civil attendants, 10 servants and six "necessary women".

- ^ John Mack Faragher, Daniel Boone, the Life and Legend of an American Pioneer, Henry Holt and Company LLC, 1992, ISBN 0-8050-3007-7, p. 38.

- ^ Frank A. Cassell. "The Braddock Expedition of 1755: Catastrophe in the Wilderness". Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on March 21, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^

Faragher, John Mack (1993) [1992]. "Curiosity is Natural: 1734 to 1755". Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 38. ISBN 978-1429997065. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

The Battle of the Monongahela [...] was one of the bloodiest and most disastrous British defeats of the eighteenth century.

- ^ Longmore, The Invention of George Washington, University of Virginia Press, 1999, p. 20

- ^ Some accounts state that Washington commanded the regiment on the Braddock Expedition, but this is incorrect. Washington did command the Virginia Regiment before and after the expedition. As a volunteer aide-de-camp, Washington essentially served as an unpaid and unranked gentleman consultant, with little real authority, but much inside access.

- ^ Similarly, Washington's report to Governor Dinwiddie. Charles H. Ambler, George Washington and the West, University of North Carolina Press, 1936, pp. 107–109.

- ^ a b c Pargellis, Stanley (1936). Military Affairs in North America 1748–1765. The American Historical Association, pp. 86–91.

Further reading

[edit]- Chartrand, Rene. Monongahela, 1754–1755: Washington's Defeat, Braddock's Disaster. United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-683-6.

- Jennings, Francis. Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton, 1988. ISBN 0-393-30640-2.

- Kopperman, Paul E. Braddock at the Monongahela. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8229-5819-8.

- O'Meara, Walter. Guns at the Forks. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1965. ISBN 0-8229-5309-9.

- Preston, David L. The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution (2015)

- Russell, Peter. "Redcoats in the Wilderness: British Officers and Irregular Warfare in Europe and America, 1740 to 1760", The William and Mary Quarterly (1978) 35#4 pp. 629–652 in JSTOR