Thylacine

| Thylacine Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A female thylacine and her juvenile offspring in the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., c. 1903[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Dasyuromorphia |

| Family: | †Thylacinidae |

| Genus: | †Thylacinus |

| Species: | †T. cynocephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Thylacinus cynocephalus | |

| |

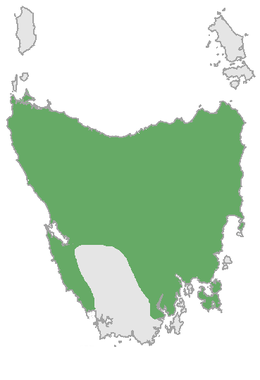

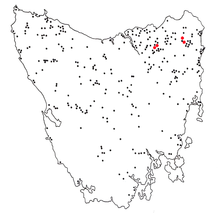

| Historic thylacine range in Tasmania (in green)[4] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List | |

The thylacine (/ˈθaɪləsiːn/; binomial name Thylacinus cynocephalus), also commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, is an extinct carnivorous marsupial that was native to the Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea. The thylacine died out in New Guinea and mainland Australia around 3,600–3,200 years ago, prior to the arrival of Europeans, possibly because of the introduction of the dingo, whose earliest record dates to around the same time, but which never reached Tasmania. Prior to European settlement, around 5,000 remained in the wild on Tasmania. Beginning in the nineteenth century, they were perceived as a threat to the livestock of farmers and bounty hunting was introduced. The last known of its species died in 1936 at Hobart Zoo in Tasmania. The thylacine is widespread in popular culture and is a cultural icon in Australia.

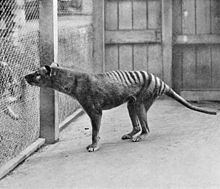

The thylacine was known as the Tasmanian tiger because of the dark transverse stripes that radiated from the top of its back, and it was called the Tasmanian wolf because it resembled a medium- to large-sized canid. The name thylacine is derived from thýlakos meaning "pouch" and ine meaning "pertaining to", and refers to the marsupial pouch. Both sexes had a pouch. The females used theirs for rearing young, and the males used theirs as a protective sheath, covering the external reproductive organs. The animal had a stiff tail and could open its jaws to an unusual extent. Recent studies and anecdotal evidence on its predatory behaviour suggest that the thylacine was a solitary ambush predator specialised in hunting small- to medium-sized prey. Accounts suggest that, in the wild, it fed on small birds and mammals. It was the only member of the genus Thylacinus and family Thylacinidae to have survived until modern times. Its closest living relatives are the other members of Dasyuromorphia, including the Tasmanian devil, from which it is estimated to have split 42–36 million years ago.

Intensive hunting on Tasmania is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributing factors were disease, the introduction of and competition with dingoes, human encroachment into its habitat and climate change. The remains of the last known thylacine were discovered at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 2022. Since extinction there have been numerous searches and reported sightings of live animals, none of which have been confirmed.

The thylacine has been used extensively as a symbol of Tasmania. The animal is featured on the official coat of arms of Tasmania. Since 1996, National Threatened Species Day has been commemorated in Australia on 7 September, the date on which the last known thylacine died in 1936. Universities, museums and other institutions across the world research the animal. Its whole genome sequence has been mapped, and there are efforts to clone and bring it back to life.[12]

Taxonomic and evolutionary history

Numerous examples of thylacine engravings and rock art have been found, dating back to at least 1000 BC.[13] Petroglyph images of the thylacine can be found at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct, on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia.[14]

By the time the first European explorers arrived, the animal was already extinct in mainland Australia and New Guinea and rare in Tasmania. Europeans may have encountered it in Tasmania as far back as 1642, when Abel Tasman first arrived in Tasmania. His shore party reported seeing the footprints of "wild beasts having claws like a Tyger".[15] Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, arriving with the Mascarin in 1772, reported seeing a "tiger cat".[16]

The first definitive encounter was by French explorers on 13 May 1792, as noted by the naturalist Jacques Labillardière, in his journal from the expedition led by d'Entrecasteaux. In 1805, William Paterson, the Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania, sent a detailed description for publication in the Sydney Gazette.[17] He also sent a description of the thylacine in a letter to Joseph Banks, dated 30 March 1805.[18]

The first detailed scientific description was made by Tasmania's Deputy Surveyor-General, George Harris, in 1808, five years after first European settlement of the island.[3][19][20] Harris originally placed the thylacine in the genus Didelphis, which had been created by Linnaeus for the American opossums, describing it as Didelphis cynocephala, the "dog-headed opossum". Recognition that the Australian marsupials were fundamentally different from the known mammal genera led to the establishment of the modern classification scheme, and in 1796, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire created the genus Dasyurus, where he placed the thylacine in 1810. To maintain gender agreement with the genus name, the species name was altered to cynocephalus. In 1824, it was separated out into its own genus, Thylacinus, by Temminck.[21] The common name derives directly from the genus name, originally from the Greek θύλακος (thýlakos), meaning "pouch" or "sack" and ine meaning "pertaining to".[22] The name is pronounced THY-lə-seen[23] or THY-lə-syne.[24]

Evolution

The earliest records of the modern thylacine are from the Early Pleistocene, with the oldest known fossil record in southeastern Australia from the Calabrian age around 1.77–0.78 million years ago.[25] Specimens from the Pliocene-aged Chinchilla Fauna, described as Thylacinus rostralis by Charles De Vis in 1894, have in the past been suggested to represent Thylacinus cynocephalus, but have been shown to either have been curatorial errors, or ambiguous in their specific attribution.[26][27][28] The family Thylacinidae includes at least 12 species in eight genera. Thylacinids are estimated to have split from other members of Dasyuromorphia around 42–36 million years ago.[28] The earliest representative of the family is Badjcinus turnbulli from the Late Oligocene of Riversleigh in Queensland,[29] around 25 million years ago.[28] Early thylacinids were quoll-sized, well under 10 kg (22 lb). It probably ate insects and small reptiles and mammals, although signs of an increasingly-carnivorous diet can be seen as early as the early Miocene in Wabulacinus.[28] Members of the genus Thylacinus are notable for a dramatic increase in both the expression of carnivorous dental traits and in size, with the largest species, Thylacinus potens and Thylacinus megiriani, both approaching the size of a wolf.[28] In late Pleistocene and early Holocene times, the modern thylacine was widespread (although never numerous) throughout Australia and New Guinea.[30]

A classic example of convergent evolution, the thylacine showed many similarities to the members of the dog family, Canidae, of the Northern Hemisphere: sharp teeth, powerful jaws, raised heels, and the same general body form. Since the thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia and New Guinea as canids did elsewhere, it developed many of the same features. Despite this, as a marsupial, it is unrelated to any of the Northern Hemisphere placental mammal predators.[31]

The thylacine is a basal member of the Dasyuromorphia, along with numbats, dunnarts, wambengers, and quolls. The cladogram follows:[32]

| Dasyuromorphia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phylogeny of Thylacinidae after Rovinsky et al. (2019)[28]

Description

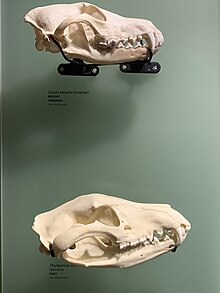

The only recorded species of Thylacinus, a genus that superficially resembles the dogs and foxes of the family Canidae, the animal was a predatory marsupial that existed on mainland Australia during the Holocene epoch and was observed by Europeans on the island of Tasmania; the species is known as the Tasmanian tiger for the striped markings of the pelage. Descriptions of the thylacine come from preserved specimens, fossil records, skins and skeletal remains, and black and white photographs and film of the animal both in captivity and from the field. The thylacine resembled a large, short-haired dog with a stiff tail which smoothly extended from the body in a way similar to that of a kangaroo.[31] The mature thylacine measured about 60 cm (24 in) in shoulder height and 1–1.3 m (3.3–4.3 ft) in body length, excluding the tail which measured around 50 to 65 cm (20 to 26 in).[33] Because the recorded body mass estimates are scant, it has been suggested that they may have weighed anywhere from 15 to 35 kg (33 to 77 lb),[28] but a 2020 study that examined 93 adult specimens, with 40 of the specimens' sexes being known, argued that their average body mass would be 16.7 kg (37 lb) with a range of 9.8–28.1 kg (22–62 lb) based on volumetric analysis.[34] There was slight sexual dimorphism, with the males being larger than females on average.[35] Males weighed on average 19.7 kg (43 lb), and females on average weighed 13.7 kg (30 lb).[34] The skull is noted to be highly convergent on those of canids, most closely resembling that of the red fox.[36]

Thylacines, uniquely for marsupials, had largely cartilaginous epipubic bones with a highly reduced osseous element.[37][38] This was once considered a synapomorphy with sparassodonts,[39] though it is now thought that both groups reduced their epipubics independently. Its yellow-brown coat featured 15 to 20 distinctive dark stripes across its back, rump and the base of its tail,[40] which earned the animal the nickname "tiger". The stripes were more pronounced in younger specimens, fading as the animal got older.[40] One of the stripes extended down the outside of the rear thigh. Its body hair was dense and soft, up to 15 mm (0.59 in) in length. Colouration varied from light fawn to a dark brown; the belly was cream-coloured.[41]

Its rounded, erect ears were about 8 cm (3.1 in) long and covered with short fur.[42] The early scientific studies suggested it possessed an acute sense of smell which enabled it to track prey,[43] but analysis of its brain structure revealed that its olfactory bulbs were not well developed. It is likely to have relied on sight and sound when hunting instead.[40] In 2017, Berns and Ashwell published comparative cortical maps of thylacine and Tasmanian devil brains, showing that the thylacine had a larger, more modularised basal ganglion. The authors associated these differences with the thylacine's more predatory lifestyle.[44] Analysis of the forebrain published in 2023 suggested that it was similar in morphology to other dasyuromorph marsupials and dissimilar to that of canids.[45]

The thylacine was able to open its jaws to an unusual extent: up to 80 degrees.[46] This capability can be seen in part in David Fleay's short black-and-white film sequence of a captive thylacine from 1933. The jaws were muscular, and had 46 teeth, but studies show the thylacine jaw was too weak to kill sheep.[42][47][48] The tail vertebrae were fused to a degree, with resulting restriction of full tail movement. Fusion may have occurred as the animal reached full maturity. The tail tapered towards the tip. In juveniles, the tip of the tail had a ridge.[49] The female thylacine had a pouch with four teats, but unlike many other marsupials, the pouch opened to the rear of its body. Males had a scrotal pouch, unique amongst the Australian marsupials,[50] into which they could withdraw their scrotal sac for protection.[40]

Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs, wombats, or Tasmanian devils, thylacines had a very large rear pad and four obvious front pads, arranged in almost a straight line.[43] The hindfeet were similar to the forefeet but had four digits rather than five. Their claws were non-retractable.[40] The plantar pad is tri-lobal in that it exhibits three distinctive lobes. It is a single plantar pad divided by three deep grooves. The distinctive plantar pad shape along with the asymmetrical nature of the foot makes it quite different from animals such as dogs or foxes.[51]

The thylacine was noted as having a stiff and somewhat awkward gait, making it unable to run at high speed. It could also perform a bipedal hop, in a fashion similar to a kangaroo—demonstrated at various times by captive specimens.[40] Guiler speculates that this was used as an accelerated form of motion when the animal became alarmed.[41] The animal was also able to balance on its hind legs and stand upright for brief periods.[52]

Observers of the animal in the wild and in captivity noted that it would growl and hiss when agitated, often accompanied by a threat-yawn. During hunting, it would emit a series of rapidly repeated guttural cough-like barks (described as "yip-yap", "cay-yip" or "hop-hop-hop"), probably for communication between the family pack members. It also had a long whining cry, probably for identification at distance, and a low snuffling noise used for communication between family members.[53] Some observers described it as having a strong and distinctive smell, others described a faint, clean, animal odour, and some no odour at all. It is possible that the thylacine, like its relative, the Tasmanian devil, gave off an odour when agitated.[54]

Distribution and habitat

The thylacine most likely preferred the dry eucalyptus forests, wetlands, and grasslands of mainland Australia.[43] Indigenous Australian rock paintings indicate that the thylacine lived throughout mainland Australia and New Guinea. Proof of the animal's existence in mainland Australia came from a desiccated carcass that was discovered in a cave in the Nullarbor Plain in Western Australia in 1990; carbon dating revealed it to be around 3,300 years old.[55] Recently examined fossilised footprints also suggest historical distribution of the species on Kangaroo Island.[56] The northernmost record of the species is from the Kiowa rock shelter in Chimbu Province in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, dating to the Early Holocene, around 10,000–8,500 years Before Present.[57] In 2017, White, Mitchell and Austin published a large-scale analysis of thylacine mitochondrial genomes, showing that they had split into eastern and western populations on the mainland prior to the Last Glacial Maximum and that Tasmanian thylacines had a low genetic diversity by the time of European arrival.[58]

In Tasmania, they preferred the woodlands of the midlands and coastal heath, which eventually became the primary focus of British settlers seeking grazing land for their livestock.[59] The striped pattern may have provided camouflage in woodland conditions,[40] but it may have also served for identification purposes.[60] The species had a typical home range of between 40 and 80 km2 (15 and 31 sq mi).[41] It appears to have kept to its home range without being territorial; groups too large to be a family unit were sometimes observed together.[61]

Ecology and behaviour

Reproduction

There is evidence for at least some year-round breeding (cull records show joeys discovered in the pouch at all times of the year), although the peak breeding season was in winter and spring.[40] They would produce up to four joeys per litter (typically two or three), carrying the young in a pouch for up to three months and protecting them until they were at least half adult size. Early pouch young were hairless and blind, but they had their eyes open and were fully furred by the time they left the pouch.[62] The young also had their own pouches that were not visible until they were 9.5 weeks old.[40] After leaving the pouch, and until they were developed enough to assist, the juveniles would remain in the lair while their mother hunted.[63] Thylacines only once bred successfully in captivity, in Melbourne Zoo in 1899.[64] Their life expectancy in the wild is estimated to have been 5 to 7 years, although captive specimens survived up to 9 years.[43]

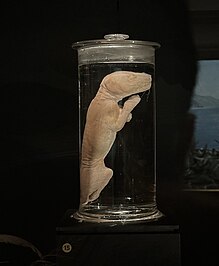

In 2018, Newton et al. collected and CT-scanned all known preserved thylacine pouch young specimens to digitally reconstruct their development throughout their entire window of growth in their mother's pouch. This study revealed new information on the biology of the thylacine, including the growth of its limbs and when it developed its 'dog-like' appearance. It was found that two of the thylacine young in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) were misidentified and of another species, reducing the number of known pouch young specimens to 11 worldwide.[65] One of four specimens kept at Museum Victoria has been serially sectioned, allowing an in-depth investigation of its internal tissues and providing some insights into thylacine pouch young development, biology, immunology and ecology.[66]

Feeding and diet

The thylacine was an apex predator,[4] though exactly how large its prey animals could be is disputed. It was a nocturnal and crepuscular hunter, spending the daylight hours in small caves or hollow tree trunks in a nest of twigs, bark, or fern fronds. It tended to retreat to the hills and forest for shelter during the day and hunted in the open heath at night. Early observers noted that the animal was typically shy and secretive, with awareness of the presence of humans and generally avoiding contact, although it occasionally showed inquisitive traits.[67] At the time, much stigma existed in regard to its "fierce" nature; this is likely to be due to its perceived threat to agriculture.[68]

Historical accounts suggest that in the wild, the thylacine preyed on small mammals and birds, with waterbirds being the most commonly recorded bird prey, with historical accounts of thylacines predating on black ducks and teals with coots, Tasmanian nativehens, swamphens, herons (Ardea) and black swans also being likely items of prey. The thylacine may also have preyed upon the now extinct Tasmanian emu.[69] The most commonly recorded mammalian prey was the red-necked wallaby, with other recorded prey including the Tasmanian pademelon and the short-beaked echidna. Other probable native mammalian prey includes other marsupials like bandicoots and brushtail possums, as well as native rodents like water rats.[70] Following their introduction to Tasmania, European rabbits rapidly multiplied and became abundant across the island, with a number of accounts reporting the predation of rabbits by thylacines.[71] Some accounts also suggest that the thylacine may have preyed on lizards, frogs and fish.[72]

European settlers believed the thylacine to prey regularly upon farmers' sheep and poultry.[a] However, analysis by Robert Paddle suggests that there is little evidence that thylacines were significant predators of sheep or poultry (though some accounts suggest that they may have attacked them on occasion), with many sheep deaths likely caused by feral dog attacks instead.[74] Throughout the 20th century, the thylacine was often characterised as primarily a blood drinker; according to Robert Paddle, the story's popularity seems to have originated from a single second-hand account heard by Geoffrey Smith (1881–1916)[75][76] in a shepherd's hut.[77]

Recent studies suggest that the thylacine was probably not suited for hunting large prey. A 2007 study argued that, while it could open its jaws wide like modern mammalian predators that consume large prey, the canine of the thylacine was not suited for slashing bites like that of large canids, indicating, based on the assumption that the bite was largely derived by its skull, that it hunted small to medium-sized prey as a solitary hunter.[78] A 2011 study by the University of New South Wales using advanced computer modelling indicated that the thylacine had surprisingly feeble jaws; animals usually take prey close to their own body size, but an adult thylacine of around 30 kg (66 lb) was found to be incapable of handling prey much larger than 5 kg (11 lb), suggesting that the thylacine only ate smaller animals such as bandicoots, pademelons and possums, and that it may have directly competed with the Tasmanian devil and the tiger quoll.[79][80] Another study in 2020 produced similar results, after estimating the average body mass of thylacine as about 16.7 kg (37 lb) rather than 30 kg (66 lb), suggesting that the animal did indeed hunt much smaller prey.[34] The cranial and facial morphology also indicate that the thylacine would have hunted prey less than 45% of its own body mass, consistent with modern carnivores weighing under 21 kg (46 lb) which is about the average size of a thylacine.[81][34]

A 2005 study showed that the thylacine had a high bite force quotient of 166, which was similar to that of most quolls, indicating that it may have been able to hunt larger prey relative to its body size.[82] A 2007 study also suggested that it would have had a much stronger bite force than a dingo of similar size, though this particular study argued that the thylacine would have hunted smaller prey.[78] A biomechanical analysis of the 3D skull model suggested that the thylacine would have likely consumed smaller prey, with its skull displaying high levels of stress that are not suited to withstand forces, and with its bite forces being estimated at a smaller value than that of Tasmanian devils.[79] A 2014 study compared the skull of a thylacine with that of modern dasyurids and an earlier thylacinid taxon Nimbacinus based on biomechanical analysis of their 3D skull models; the authors suggested that while Nimbacinus was suited to hunt large prey with a maximum muscle force of 651 N (146 lbf) which are similar to that of large Tasmanian devils, the thylacine skull displayed a much higher stress in all areas compared to its relatives due to its longer snout.[80] If the thylacine were indeed specialised for small prey, this specialisation likely made it susceptible to small disturbances to the ecosystem.[79]

It has been suggested on the basis of the canine teeth and limb bones that the thylacine was a solitary pounce-pursuit predator that hunted smaller prey with trophic niches similar to relatively smaller canids like the coyote, and that it was not as specialised as large canids, hyaenids and felids of today: its canine lacked the adaptation for producing slashing or deep penetrating bites, and its anatomy was not suited for running fast in high speed.[83][84] However, the trappers reported it as an ambush predator hunting alone or in pairs mainly at night.[40][85] The elbow joint morphology and the forelimb anatomy of the thylacine also suggest that the animal was most likely an ambush predator.[86][87]

The stomach of a thylacine was very muscular, capable of distending to allow the animal to eat large amounts of food at one time, probably an adaptation to compensate for long periods when hunting was unsuccessful and food scarce.[40] In captivity, thylacines were fed a wide variety of foods, including dead rabbits and wallabies as well as beef, mutton, horse and, occasionally, poultry.[88] There is a report of a captive thylacine that refused to eat dead wallaby flesh or to kill and eat a live wallaby offered to it, but "ultimately it was persuaded to eat by having the smell of blood from a freshly killed wallaby put before its nose."[89]

Extinction

Dying out on the Australian mainland

Australia lost more than 90% of its megafauna around 50–40,000 years ago as part of the Quaternary extinction event, with the notable exceptions of several kangaroo and wombat species, emus, cassowaries, large goannas, and the thylacine. The extinctions included the even larger carnivore Thylacoleo carnifex (sometimes called the marsupial lion) which was only distantly related to the thylacine.[90] A 2010 paper examining this issue showed that humans were likely to be one of the major factors in the extinction of many species in Australia although the authors of the research warned that one-factor explanations might be over-simplistic.[90] The youngest radiocarbon dates of the thylacine in mainland Australia are around 3,500 years old, with an estimated extinction date around 3,200 years ago, synchronous with that of Tasmanian devil, and closely co-inciding with the earliest records of the dingo, as well as an intensification of human activity.[91]

A study proposes that the dingo may have led to the extinction of the thylacine in mainland Australia because the dingo outcompeted the thylacine in preying on the Tasmanian nativehen. The dingo is also more likely to hunt in packs than the more solitary thylacine.[92] Examinations of dingo and thylacine skulls show that although the dingo had a weaker bite, its skull could resist greater stresses, allowing it to pull down larger prey than the thylacine. Because it was a hypercarnivore, the thylacine was less versatile in its diet than the omnivorous dingo.[93][78] Their ranges appear to have overlapped because thylacine subfossil remains have been discovered near those of dingoes. Aside from wild dingoes, the adoption of the dingo as a hunting companion by the indigenous peoples would have put the thylacine under increased pressure.[92]

A 2013 study suggested that, while dingoes were a contributing factor to the thylacine's demise on the mainland, larger factors were the intense human population growth, technological advances, and the abrupt change in the climate during the period.[94][95] A report published in the Journal of Biogeography detailed an investigation into the mitochondrial DNA and radio-carbon dating of thylacine bones. It concluded that the thylacine died out on mainland Australia in a relatively short time span.[96]

Ken Mulvaney has suggested, based on the high number of rock carvings of the thylacine on the Burrup Peninsula, Aboriginal Australians were aware of, and concerned about the thylacine’s dwindling numbers around that time.[97][98]

Dying out on Tasmania

Although the thylacine had died out on mainland Australia, it survived into the 1930s on the island of Tasmania. At the time of the first European settlement, the heaviest distributions were in the northeast, northwest and north-midland regions of the state.[59] There were an estimated 5,000 at the time.[99] They were rarely sighted but slowly began to be credited with numerous attacks on sheep. This led to the establishment of bounty schemes in an attempt to control their numbers. The Van Diemen's Land Company introduced bounties on the thylacine from as early as 1830, and between 1888 and 1909, the Tasmanian government paid £1 per head for dead adult thylacines and ten shillings for pups. In all, they paid out 2,184 bounties, but it is thought that many more thylacines were killed than were claimed for. Its extinction is popularly attributed to these relentless efforts by farmers and bounty hunters.[43][100][101]

Aside from persecution, it is likely that multiple factors rapidly compounded its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs introduced by European settlers,[102] erosion of its habitat, already-low genetic diversity, the concurrent extinction or decline of prey species, and a distemper-like disease that affected many captive specimens at the time.[41][103] A study from 2012 suggested that the disease was likely introduced by humans, and that it was also present in the wild population. The marsupi-carnivore disease, as it became known, dramatically reduced the lifespan of the animal and greatly increased pup mortality.[104]

A 1921 photo by Henry Burrell of a thylacine with a chicken was widely distributed and may have helped secure the animal's reputation as a poultry thief. The image had been cropped to hide the fact that the animal was in captivity, and analysis by one researcher has concluded that this thylacine was a dead specimen, posed for the camera. The photograph may even have involved photo manipulation.[105][106]

The animal had become extremely rare in the wild by the late 1920s. Despite the fact that the thylacine was believed by many to be responsible for attacks on sheep, in 1928 the Tasmanian Advisory Committee for Native Fauna recommended a reserve similar to the Savage River National Park to protect any remaining thylacines, with potential sites of suitable habitat including the Arthur-Pieman area of western Tasmania.[107]

By the beginning of the 20th century, the increasing rarity of thylacines led to increased demand for captive specimens by zoos around the world, placing yet more pressure on an already small population.[108] Despite the export of breeding pairs, attempts at rearing thylacines in captivity were unsuccessful, and the last thylacine outside Australia died at the London Zoo in 1931.[109]

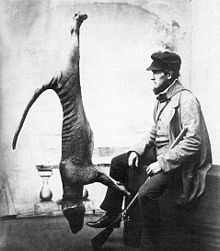

The last known thylacine to be killed in the wild was shot in 1930 by Wilf Batty, a farmer from Mawbanna in the state's northwest. The animal, believed to have been a male, had been seen around Batty's house for several weeks.[110][111]

Work in 2012 examined the relationship of the genetic diversity of the thylacines before their extinction. The results indicated that the last of the thylacines in Tasmania had limited genetic diversity due to their complete geographic isolation from mainland Australia.[112] Further investigations in 2017 showed evidence that this decline in genetic diversity started long before the arrival of humans in Australia, possibly starting as early as 70–120 thousand years ago.[36]

The thylacine held the status of endangered species until the 1980s. International standards at the time stated that an animal could not be declared extinct until 50 years had passed without a confirmed record. Since no definitive proof of the thylacine's existence in the wild had been obtained for more than 50 years, it met that official criterion and was declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 1982[2] and by the Tasmanian government in 1986. The species was removed from Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in 2013.[113]

Last of the species

This section appears to contradict the article Endlings. (March 2024) |

The last captive thylacine, lived as an endling (the known last of its species) at Hobart Zoo until its death on the night of 7 September 1936.[114] The animal, a female,[115] was captured by Elias Churchill with a snare trap and was sold to the zoo in May 1936. The sale was not publicly announced because the use of traps was illegal and Churchill could have been fined.[114] After its death, the remains of the endling were transferred to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. The remains were not properly recorded by the museum because the animal had been caught illegally. It lay undiscovered for decades until a taxidermist record dated from 1936 or 1937 mentioning the animal was noticed. This led to a full audit of all thylacine remains at the museum and the endling's successful identification at the end of 2022.[116]

In 1968, Frank Darby[further explanation needed] invented a myth that the endling was called Benjamin. The myth was widely circulated in the media, with Wikipedia itself repeating the invention.[115] The thylacine that Darby was referring to was a female at Hobart Zoo.[115] This animal is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of its sheltered sleeping quarters, it was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night.[117] This thylacine features in the last known motion picture footage of a living specimen: 45 seconds of black-and-white footage showing the thylacine in its enclosure in a clip taken in 1933, by naturalist David Fleay.[118] In the film footage, the thylacine is seen seated, walking around the perimeter of its enclosure, yawning, sniffing the air, scratching itself (in the same manner as a dog), and lying down. Fleay was bitten on the buttock whilst shooting the film.[118] In 2021, a digitally colourised 80-second clip of Fleay's footage of the thylacine was released by the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, to mark National Threatened Species Day. The digital colourisation process was based on historic primary and secondary descriptions to ensure an accurate colour match.[119][120]

Although there had been a conservation movement pressing for the thylacine's protection since 1901, driven in part by the increasing difficulty in obtaining specimens for overseas collections, political difficulties prevented any form of protection coming into force until 1936. Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government came all too late; it was introduced on 10 July 1936, 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.[121]

Searches and unconfirmed sightings

Between 1967 and 1973, zoologist Jeremy Griffith and dairy farmer James Malley conducted what is regarded as the most intensive search for thylacines ever carried out, including exhaustive surveys along Tasmania's west coast, installation of automatic camera stations, prompt investigations of claimed sightings, and in 1972 the creation of the Thylacine Expeditionary Research Team with Dr. Bob Brown, which concluded without finding any evidence of the thylacine's existence.[122]

The Department of Conservation and Land Management recorded 203 reports of sightings of the thylacine in Western Australia from 1936 to 1998.[67] On the mainland, sightings are most frequently reported in Southern Victoria.[123]

According to the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, there have been eight unconfirmed thylacine sighting reports between 2016 and 2019, with the latest unconfirmed visual sighting on 25 February 2018.[124]

Since the disappearance and effective extinction of the thylacine, speculation and searches for a living specimen have become a topic of interest to some members of the cryptozoology subculture.[125] The search for the animal has been the subject of books and articles, with many reported sightings that are largely regarded as dubious.[126]

A 2023 study published by Brook et al. compiles many of the alleged sightings of thylacines in Tasmania throughout the 20th century and claims that, contrary to beliefs that the thylacine went extinct in the 1930s, the Tasmanian thylacine may have actually lasted throughout the 20th century, with a window of extinction between the 1980s and the present day and the likely extinction date being between the late 1990s and early 2000s.[127][128]

In 1983, the American media mogul Ted Turner offered a $100,000 reward for proof of the continued existence of the thylacine.[129][130] In March 2005, Australian news magazine The Bulletin, as part of its 125th anniversary celebrations, offered a $1.25 million reward for the safe capture of a live thylacine. When the offer closed at the end of June 2005, no one had produced any evidence of the animal's existence. An offer of $1.75 million has subsequently been offered by a Tasmanian tour operator, Stewart Malcolm.[131]

Research

Research into thylacines relies heavily on specimens held in museums and other institutions across the world. The number and distribution of these specimens has been recorded in the International Thylacine Specimen Database. As of 2022, 756 specimens are held in 115 museums and university collections in 23 countries.[132] In 2017, a reference library of 159 micrographic images of thylacine hair was jointly produced by CSIRO and Where Light Meets Dark.[133]

Cloning

The Australian Museum in Sydney began a cloning project in 1999.[134] The goal was to use genetic material from specimens taken and preserved in the early 20th century to clone new individuals and restore the species from extinction. Several molecular biologists dismissed the project as a public relations stunt.[135] In late 2002, the researchers had some success as they were able to extract replicable DNA from the specimens.[136] On 15 February 2005, the museum announced that it was stopping the project.[137][138] In May 2005, the project was restarted by a group of interested universities and a research institute.[131][139]

In August 2022, it was announced that the University of Melbourne would partner with Texas-based biotechnology company Colossal Biosciences to attempt to re-create the thylacine using its closest living relative, the fat-tailed dunnart, and return it to Tasmania.[140] The university had recently sequenced the genome of a juvenile thylacine specimen and was establishing a thylacine genetic restoration laboratory.[141][142][143][144][145] The research from the University of Melbourne was led by Andrew Pask.[146] The project was regarded with skepticism by other, uninvolved scientists.[146]

DNA sequencing

A draft whole genome sequencing of the thylacine was produced by Feigin et al. (2017) using the DNA extracted from an ethanol-preserved pouch of a young specimen provided by Museums Victoria. The neonatal development of the thylacine was also reconstructed from preserved pouch young specimens from several museum collections.[147] Researchers used the genome to study aspects of the thylacine's evolution and natural history, including the genetic basis of its convergence with canids, clarifying its evolutionary relationships with other marsupials and examining changes in its population size over time.[148]

The genomic basis of the convergent evolution between the thylacine and grey wolf was further investigated in 2019,[149] with researchers identifying many non-coding genomic regions displaying accelerated rates of evolution, a test for genetic regions evolving under positive selection. In 2021,[150] researchers further identified a link between the convergent skull shapes of the thylacine and wolf,[148] and the previously identified genetic candidates.[149] It was reported that specific groups of skull bones, which develop from a common population of stem cells called neural crest cells, showed strong similarity between the thylacine and wolf[150] and corresponded with the underlying convergent genetic candidates which influence these cells during development.[149] In 2023, RNA was extracted from a 130-year-old thylacine specimen in Sweden; this represented the first time RNA has been extracted from an extinct species.[151] In 2024, a 99.9% thylacine genome was sequenced from a well-preserved skull that is estimated to be 110-year-old.[12][152]

Cultural significance

Official usage

The thylacine has been used extensively as a symbol of Tasmania. The animal is featured on the official Tasmanian coat of arms.[153] It is used in the official logos for the Tasmanian government and the City of Launceston.[153] It is also used on the University of Tasmania's ceremonial mace and the badge of the submarine HMAS Dechaineux.[153] Since 1998, it has been prominently displayed on Tasmanian vehicle number plates.[citation needed] The thylacine has appeared in postage stamps from Australia, Equatorial Guinea, and Micronesia.[154]

Since 1996,[155] 7 September (the date in 1936 on which the last known thylacine died) has been commemorated in Australia as National Threatened Species Day.[156]

In popular culture

The thylacine has become a cultural icon in Australia.[157] The best known illustrations of Thylacinus cynocephalus were those in John Gould's The Mammals of Australia (1845–1863), often copied since its publication and the most frequently reproduced,[158] and given further exposure by Cascade Brewery's appropriation for its label in 1987.[159] The government of Tasmania published a monochromatic reproduction of the same image in 1934,[160] the author Louisa Anne Meredith also copied it for Tasmanian Friends and Foes (1881).[158] The thylacine is the mascot for the Tasmanian cricket team.[161] A series of postage stamps that feature Mickey Mouse characters with Australian animals features a thylacine stamp in the collection.[162]

In video games, boomerang-wielding Ty the Tasmanian Tiger is the star of his own trilogy during the 2000s.[163] Tiny Tiger, a villain in the popular Crash Bandicoot video game series, is a mutated thylacine.[164] In Valorant, agent Skye has the ability to use a Tasmanian tiger to scout enemies and clear bomb-planting sites.[165]

The animal has made appearance in film and television. Characters in the early 1990s' cartoon Taz-Mania included the neurotic Wendell T. Wolf, the last surviving Tasmanian wolf.[166] The Hunter is a 2011 Australian drama film, based on the 1999 novel of the same name by Julia Leigh. It stars Willem Dafoe, who plays a man hired to track down the Tasmanian tiger.[167] In the 2021 film, Extinct, a thylacine named Burnie, along with a group of other extinct animals, help the movie's main characters travel through time to rescue their species from extinction.[168] In the 2022 science-fiction show The Peripheral the Tasmanian tiger is brought back into existence from DNA extracts.[169] An animated web series titled "De-extincting Tasie" meant to explain the revival of the species by Colossal Biosciences and University of Melbourne features a thylacine named Tasie, a satire of the Mr. DNA character from the Jurassic Park media franchise.[170]

In Aboriginal tradition

Rock art featuring Thylacine-like animals are found throughout Northern Australia, particularly in the Kimberley region.[171]

Various Aboriginal Tasmanian names for the thylacine have been recorded, such as coorinna, kanunnah, cab-berr-one-nen-er, loarinna, laoonana, can-nen-ner and lagunta,[172][173] while kaparunina is used in Palawa kani.[174][175]

One Nuenonne myth recorded by Jackson Cotton tells of a thylacine pup saving Palana, a spirit boy, from an attack by a giant kangaroo. Palana marked the pup's back with ochre as a mark of its bravery, giving thylacines their stripes.[176] A constellation, "Wurrawana Corinna" (identified as within or near Gemini), was also created as a commemoration of this mythic act of bravery.[177]

An early European record tells how Aboriginals believed bad weather was caused by a Thylacine carcass being left exposed on the ground, instead of being covered by a small shelter.[178]

See also

Notes

- ^ Based on the lack of reliable first hand accounts, Robert Paddle argues that the predation on sheep and poultry may have been exaggerated, suggesting the thylacine was used as a convenient scapegoat for the mismanagement of the sheep farms, and the image of it as a poultry killer impressed on the public consciousness by a striking photo taken by Henry Burrell in 1921.[73]

References

Citations

- ^ Sleightholme, Stephen R.; Campbell, Cameron R. (30 September 2020). "A Catalogue of the Thylacine captured on film" (PDF). Australian Zoologist. 41 (2): 143–178. doi:10.7882/AZ.2020.032. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Burbidge, A. A.; Woinarski, J. (2016). "Thylacinus cynocephalus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T21866A21949291. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T21866A21949291.en. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Harris, G. P. (1808). "Description of two new Species of Didelphis from Van Diemen's Land". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 9 (1): 174–178. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1818.tb00336.x. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ a b Paddle (2000)

- ^ Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire, [Étienne] (1810). "Description de deux espèces de Dasyures (Dasyurus cynocephalus et Dasyurus ursinus)". Annales du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. 15: 301–306. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Temminck, C. J. (1827). "Thylacine de Harris. – Thylacinus harrisii". Monographies de mammalogie. Vol. 1. Paris: G. Dufour et Ed. d'Ocagne. pp. 63–65.

- ^ Grant, J. (1831). "Notice of the Van Diemen's Land Tiger". Gleanings in Science. 3 (30): 175–177. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Warlow, W. (1833). "Systematically arranged Catalogue of the Mammalia and Birds belonging to the Museum of the Asiatic Society, Calcutta". The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 2 (14): 97. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ "Genus Thylacinus, Temm.". Descriptive Catalogue of the Specimens of Natural History in Spirit Contained in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Vertebrata: Pisces, Reptilia, Aves, Mammalia. London: Taylor and Francis. 1859. p. 147.

- ^ Krefft, Gerard (1868). "Description of a new species of Thylacine (Thylacinus breviceps)". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Fourth Series. 2 (10): 296–297. doi:10.1080/00222936808695804. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ De Vis, C. W. (1894). "A thylacine of the earlier nototherian period in Queensland". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 8: 443–447. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ a b Le Page, Michael (26 October 2024). "De-extinction company claims it has a nearly complete thylacine genome". New Scientist. p. 11.

- ^ Salleh, Anna (15 December 2004). "Rock art shows attempts to save thylacine". ABC Science Online. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ Mulvaney, Ken J. (2009). "Dating the Dreaming: Extinct fauna in the petroglyphs of the Pilbara region, Western Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. 44: 40–48. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.2009.tb00067.x.

- ^ Rembrants, D. (1682). "A short relation out of the journal of Captain Abel Jansen Tasman, upon the discovery of the South Terra incognita; not long since published in the Low Dutch". Philosophical Collections of the Royal Society of London (6): 179–186. Quoted in Paddle (2000), p. 3.

- ^ Roth, H. L. (1891) "Crozet's Voyage to Tasmania, New Zealand, etc. ... 1771–1772.". London. Truslove and Shirley. Quoted in Paddle (2000), p. 3.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 3.

- ^ Description of a Tasmanian Tiger Received by Banks from William Paterson, 30 March 1805. (n.d.). Sir Joseph Banks Papers, State Library of New South Wales, SAFE/Banks Papers/Series 27.33 Archived 9 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Information sheet: Thylacine Thylacinus cynocephalus" (PDF). museum.vic.gov.au. Victoria Museum. April 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ "Thylacinus cynocephalus (Harris, 1808)". Australian Faunal Directory. Australian Biological Resources Study. 9 October 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 5.

- ^ Hoad, T. F., ed. (1986). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-863120-0.

- ^ Macquarie ABC Dictionary. The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. 2003. p. 1032. ISBN 978-1-876429-37-9.

- ^ "thylacine". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Piper, Katarzyna J. (2007). "Early Pleistocene mammals from the Nelson Bay local fauna, Portland, Victoria, Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 492–503. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[492:EPMFTN]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130610478.

- ^ Mackness, B. S., et al. "Confirmation of Thylacinus from the Pliocene Chinchilla Local Fauna". Australian Mammalogy. 24.2 (2002): 237–242.

- ^ Jackson, S.M.; Groves, C. (2015). Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 9781486300136.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rovinsky, Douglass S.; Evans, Alistair R.; Adams, Justin W. (2019). "The pre-Pleistocene fossil thylacinids (Dasyuromorphia: Thylacinidae) and the evolutionary context of the modern thylacine". PeerJ. 7. e7457. doi:10.7717/peerj.7457. PMC 6727838. PMID 31534836.

- ^ Muirhead, J.; Wroe, S. (1998). "A new genus and species, Badjcinus turnbulli (Thylacinidae: Marsupialia), from the late Oligocene of Riversleigh, northern Australia, and an investigation of thylacinid phylogeny". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (3): 612–626. Bibcode:1998JVPal..18..612M. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011088.

- ^ Johnson, C. N.; Wroe, S. (November 2003). "Causes of extinction of vertebrates during the Holocene of mainland Australia: arrival of the dingo, or human impact?". The Holocene. 13 (6): 941–948. Bibcode:2003Holoc..13..941J. doi:10.1191/0959683603hl682fa. S2CID 15386196.

- ^ a b "Threatened Species: Thylacine – Tasmanian tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus" (PDF). parks.tas.gov.au. Parks and Wildlife Service, Tasmania. December 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ Miller, W; Drautz, DI; Janecka, JE; et al. (February 2009). "The mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus)". Genome Res. 19 (2): 213–220. doi:10.1101/gr.082628.108. PMC 2652203. PMID 19139089.

- ^ Bryant, Sally; Jackson, Jean; Threatened Species Unit, Parks & Wildlife Service, Tasmania (1999). Tasmania's Threatened Fauna Handbook (PDF). Bryant and Jackson. pp. 190–193. ISBN 978-0-7246-6223-4.

- ^ a b c d Rovinsky, Douglass S.; Evans, Alistair R.; Martin, Damir G.; Adams, Justin W. (2020). "Did the thylacine violate the costs of carnivory? Body mass and sexual dimorphism of an iconic Australian marsupial". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287 (20201537). doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.1537. PMC 7482282. PMID 32811303.

- ^ Jones, Menna (1997). "Character displacement in Australian dasyurid carnivores: size relationships and prey size patterns". Ecology. 78 (8): 2569–2587. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[2569:CDIADC]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Feigin, Charles Y.; Newton, Alex H.; Doronina, Liliya; et al. (11 December 2017). "Genome of the Tasmanian tiger provides insights into the evolution and demography of an extinct marsupial carnivore". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (1): 182–192. Bibcode:2017NatEE...2..182F. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0417-y. PMID 29230027.

- ^ Campbell, Cameron. "The Thylacine Museum – Biology: Anatomy: Skull and Skeleton: Post-cranial Skeleton (page 1)". Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Ronald M. Nowak, Walker's Marsupials of the World, JHU Press, 12 September 2005

- ^ Marshall, L. Evolution of the Borhyaenidae, extinct South American predaceous marsupials. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dixon, Joan. "Fauna of Australia chap.20 vol.1b" (PDF). Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS). Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ a b c d Guiler, Eric (2006). "Profile – Thylacine". Zoology Department, University of Tasmania. Archived from the original on 18 July 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ a b "Australia's Thylacine: What did the Thylacine look like?". Australian Museum. 1999. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Wildlife of Tasmania: Mammals of Tasmania: Thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus". Parks and Wildlife Service, Tasmania. 2006. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ Berns, Gregory S.; Ashwell, Ken W. S. (18 January 2017). "Reconstruction of the Cortical Maps of the Tasmanian Tiger and Comparison to the Tasmanian Devil". PLOS ONE. 12 (1): e0168993. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1268993B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168993. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5242427. PMID 28099446.

- ^ Haines, Elizabeth; Bailey, Evan; Nelson, John; Fenlon, Laura R.; Suárez, Rodrigo (8 August 2023). "Clade-specific forebrain cytoarchitectures of the extinct Tasmanian tiger". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (32): e2306516120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12006516H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2306516120. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 10410726. PMID 37523567.

- ^ AFP (21 October 2003). "Extinct Thylacine May Live Again". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- ^ "Tasmanian Tiger's Jaw Was Too Small to Attack Sheep, Study Shows" Archived 23 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Science Daily. 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Tasmanian tiger was no sheep killer" Archived 4 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. ABC Science. 1 September 2011.

- ^ "The Thylacine Museum: External Antatomy". Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ The scrotal pouch is almost unique within the marsupials – the only other marsupial species to have this feature is the water opossum, Chironectes minimus, which is found in Mexico and Central and South America.

- ^ "Foot cast of a freshly dead thylacine: Thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus". Victoria Museum, Victoria. 2015. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Tasmanian Tiger". Archives Office of Tasmania. 1930. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 49.

- ^ "Mummified thylacine has national message". National Museum of Australia, Canberra. 16 June 2004. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Fedorowytsch, T. 2017. Fossil footprints reveal Kangaroo Island's diverse ancient wildlife. Archived 24 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. ABC Net News. Retrieved on 24 July 2017.

- ^ Gaffney, Dylan; Summerhayes, Glenn R.; Luu, Sindy; Menzies, James; Douglass, Kristina; Spitzer, Megan; Bulmer, Susan (February 2021). "Small game hunting in montane rainforests: Specialised capture and broad spectrum foraging in the Late Pleistocene to Holocene New Guinea Highlands". Quaternary Science Reviews. 253. 106742. Bibcode:2021QSRv..25306742G. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106742. S2CID 234011303.

- ^ White, Lauren C.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Austin, Jeremy J. (2018). "Ancient mitochondrial genomes reveal the demographic history and phylogeography of the extinct, enigmatic thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus)". Journal of Biogeography. 45 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:2018JBiog..45....1W. doi:10.1111/jbi.13101. ISSN 1365-2699. S2CID 91011378.

- ^ a b "Australia's Thylacine: Where did the Thylacine live?". Australian Museum. 1999. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 42–43.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Newton, Axel H.; Spoutil, Frantisek; Prochazka, Jan; Black, Jay R.; Medlock, Kathryn; Paddle, Robert N.; Knitlova, Marketa; Hipsley, Christy A.; Pask, Andrew J. (21 February 2018). "Letting the 'cat' out of the bag: pouch young development of the extinct Tasmanian tiger revealed by X-ray computed tomography". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (2): 171914. Bibcode:2018RSOS....571914N. doi:10.1098/rsos.171914. PMC 5830782. PMID 29515893.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 60.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 228–231.

- ^ Newton, Axel H.; Spoutil, Frantisek; Prochazka, Jan; Black, Jay R.; Medlock, Kathryn; Paddle, Robert N.; Knitlova, Marketa; Hipsley, Christy A.; Pask, Andrew J. (21 February 2018). "Letting the 'cat' out of the bag: pouch young development of the extinct Tasmanian tiger revealed by X-ray computed tomography". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (2): 171914. Bibcode:2018RSOS....571914N. doi:10.1098/rsos.171914. PMC 5830782. PMID 29515893.

- ^ Old, Julie M. (2015). "Immunological Insights into the Life and Times of the Extinct Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus)". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0144091. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1044091O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144091. PMC 4684372. PMID 26655868.

- ^ a b Heberle, G. (1977). "Reports of alleged thylacine sightings in Western Australia" (PDF). Sunday Telegraph: 46. Archived from the original (w) on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Tasmanian tigers brought to life Archived 12 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Geographic, 24 February 2011.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 81.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 79–80.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p 84.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p 82.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 79–138.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 83-138.

- ^ Smith, Geoffrey Watkins (1909) "A Naturalist in Tasmania." Archived 10 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

- ^ "Smith, Geoffrey Watkins" Archived 3 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. winchestercollegeatwar.com.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 29–35.

- ^ a b c Wroe, Stephen; Clausen, Philip; McHenry, Colin; Moreno, Karen; Cunningham, Eleanor (2007). "Computer simulation of feeding behaviour in the thylacine and dingo as a novel test for convergence and niche overlap". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1627): 2819–2828. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0906. PMC 2288692. PMID 17785272.

- ^ a b c Attard, M. R. G.; Chamoli, U.; Ferrara, T. L.; Rogers, T. L.; Wroe, S. (2011). "Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: The thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted-tailed quoll". Journal of Zoology. 285 (4): 292. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00844.x.

- ^ a b Attard, Marie R. G.; Parr, William C. H.; Wilson, Laura A. B.; Archer, Michael; Hand, Suzanne J.; Rogers, Tracey L.; Wroe, Stephen (2014). "Virtual Reconstruction and Prey Size Preference in the Mid Cenozoic Thylacinid, Nimbacinus dicksoni (Thylacinidae, Marsupialia)". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e93088. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...993088A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093088. PMC 3981708. PMID 24718109.

- ^ Rovinsky, Douglass S.; Evans, Alistair R.; Adams, Justin W. (2021). "Functional ecological convergence between the thylacine and small prey-focused canids". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 21 (1). 58. doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01788-8. PMC 8059158. PMID 33882837.

- ^ Wroe, S.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. (2005). "Bite club: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1563): 619–625. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. PMC 1564077. PMID 15817436.

- ^ Jones, M. E.; Stoddart, D. M. (1998). "Reconstruction of the predatory behaviour of the extinct marsupial thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus)". Journal of Zoology. 246 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00152.x.

- ^ Jones, M. E. (2003). "Convergence in ecomorphology and guild structure among marsupial and placental carnivores". In Jones, M. E.; Dickman, C.; Archer, A. (eds.). Predators with Pouches: The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 285–296. ISBN 9780643066342.

- ^ Janis, C.M.; Wilhelm, P.B. (1993). "Were there mammalian pursuit predators in the Tertiary? Dances with wolf avatars". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 1 (2): 103–125. doi:10.1007/bf01041590. S2CID 22739360.

- ^ Figueirido, B.; Janis, C.M. (2011). "The predatory behaviour of the thylacine: Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf?". Biology Letters. 7 (6): 937–940. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0364. PMC 3210661. PMID 21543392.

- ^ Janis, C.M.; Figueirido, B. (2014). "Forelimb anatomy and the discrimination of the predatory behavior of carnivorous mammals: The thylacine as a case study". Journal of Morphology. 275 (12): 1321–1338. doi:10.1002/jmor.20303. PMID 24934132. S2CID 25924022.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 96.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 32.

- ^ a b Prideaux, Gavin J.; Gully, Grant A.; Couzens, Aidan M. C.; Ayliffe, Linda K.; Jankowski, Nathan R.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Roberts, Richard G.; Hellstrom, John C.; Gagan, Michael K.; Hatcher, Lindsay M. (December 2010). "Timing and dynamics of Late Pleistocene mammal extinctions in southwestern Australia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (51): 22157–22162. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10722157P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011073107. PMC 3009796. PMID 21127262.

- ^ White, Lauren C.; Saltré, Frédérik; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Austin, Jeremy J. (January 2018). "High-quality fossil dates support a synchronous, Late Holocene extinction of devils and thylacines in mainland Australia". Biology Letters. 14 (1): 20170642. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0642. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 5803592. PMID 29343562.

- ^ a b Johnson, C. N.; Wroe, S. (September 2003). "Causes of Extinction of Vertebrates during the Holocene of Mainland Australia: Arrival of the Dingo, or Human Impact?". The Holocene. 13 (6): 941–948. Bibcode:2003Holoc..13..941J. doi:10.1191/0959683603hl682fa. S2CID 15386196.

- ^ "Tiger's demise: Dingo did do it". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Prowse, Thomas A. A.; Johnson, Christopher N.; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Brook, Barry W. (March 2014). "An ecological regime shift resulting from disrupted predator–prey interactions in Holocene Australia". Ecology. 95 (3): 693–702. Bibcode:2014Ecol...95..693P. doi:10.1890/13-0746.1. ISSN 0012-9658. PMID 24804453.

- ^ "Dingo wrongly blamed for extinctions". phys.org. University of Adelaide. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Jones, Cheryl (27 September 2017). "Climate killed thylacine on mainland Australia". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023.

- ^ Salleh, Anna (15 December 2004). "Rock art shows attempts to save thylacine". ABC Science. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Mulvaney, Ken J. (2023). "The relevance of rock art in understanding the thylacine's mainland extinction chronology". In Holmes, Branden (ed.). Thylacine: The History, Ecology and Loss of the Tasmanian Tiger. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 51–54. ISBN 9781486315536.

- ^ Owen 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Jarvis, Brooke (2 July 2018). "The Obsessive Search for the Tasmanian Tiger Could a global icon of extinction still be alive?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "National Museum of Australia – Extinction of thylacine".

- ^ Boyce, James (2006). "Canine Revolution: The Social and Environmental Impact of the Introduction of the Dog to Tasmania". Environmental History. 11 (1): 102–129. doi:10.1093/envhis/11.1.102. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009.

- ^ Paddle (2000), pp. 202–203.

- ^ Paddle, R. (2012). "The thylacine's last straw: Epidemic disease in a recent mammalian extinction". Australian Zoologist. 36 (1): 75–92. doi:10.7882/az.2012.008. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Freeman, Carol (June 2005). "Is this picture worth a thousand words? An analysis of Henry Burrell's photograph of a thylacine with a chicken" (PDF). Australian Zoologist. 33 (1): 1–15. doi:10.7882/AZ.2005.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2012.

- ^ See Freeman, Carol (2014). Paper Tiger: How Pictures Shaped the Thylacine (illustrated ed.). Hobart, Tasmania: Forty South Publishing. ISBN 978-0992279172.

- ^ "Pelt of a thylacine shot in the Pieman River-Zeehan area of Tasmania in 1930: Charles Selby Wilson collection". National Museum of Australia, Canberra. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Department of the Environment (2018). Thylacinus cynocephalus Archived 8 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine in Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Edmonds, Penny; Stark, Hannah (5 April 2018). "Friday essay: on the trail of the London thylacines". The Conversation. Academic Journalism Society. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Ley, Willy (December 1964). "The Rarest Animals". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–103.

- ^ "History – Persecution – (page 10)". The Thylacine Museum. 2006. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ Menzies, Brandon R.; Renfree, Marilyn B.; Heider, Thomas; Mayer, Frieder; Hildebrandt, Thomas B.; Pask, Andrew J. (18 April 2012). "Limited Genetic Diversity Preceded Extinction of the Tasmanian Tiger". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35433. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735433M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035433. PMC 3329426. PMID 22530022.

- ^ "Amendments to Appendices I and II of the Convention" (PDF). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 19 April 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Thylacine mystery solved in TMAG collections". Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

- ^ a b c Dunlevie, James (5 December 2022). "Stop calling the last thylacine Benjamin, Tasmanian tiger researcher says". ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Tasmanian tiger: remains of the last-known thylacine unearthed in museum". the Guardian. 5 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 195.

- ^ a b Dayton, Leigh (19 May 2001). "Rough Justice". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Footage of last-known surviving Tasmanian tiger remastered and released in 4K colour ABC News, 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Extinct Tasmanian tiger brought to life in colour footage". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Paddle (2000), p. 184.

- ^ Park, Andy (July 1986). "Tasmanian tiger – extinct or merely elusive?". Australian Geographic. 1 (3): 66–83.

- ^ "Thyla seen near CBD?". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 August 2003. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Dalton, Jane. "The last Tasmanian tiger is thought to have died more than 80 years ago. But 8 recent sightings suggest the creature may not be gone". Business Insider.

- ^ Loxton, Daniel and Donald Prothero. Abominable Science!: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids, p. 323 & 327. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15321-8

- ^ Fuller, Errol (2013). Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 170, 178. ISBN 9781408172155.

- ^ Brook, Barry W.; Sleightholme, Stephen R.; Campbell, Cameron R.; Jarić, Ivan; Buettel, Jessie C. (2023). "Resolving when (and where) the Thylacine went extinct". Science of the Total Environment. 877. 162878. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.87762878B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162878. PMID 36934937.

- ^ Worthington, Jackson (25 January 2021). "Tracking the extinction of the Tasmanian tiger". The Ararat Advertiser. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Steger, Jason (26 March 2005). "Extinct or not, the story won't die". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ McAllister, Murray (2000). "Reward Monies Withdrawn". Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ a b Dasey, Daniel (15 May 2005). "Researchers revive plan to clone the Tassie tiger". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ "The Thylacine Museum – Biology: The Specimens (page 1)". naturalworlds. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Rehberg, C. (2017) Photomicrographs of thylacine hair Archived 14 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au Archived 14 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leigh, Julia (30 May 2002). "Back from the dead". The Guardian. London, England. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ "Tasmanian tiger clone a fantasy: scientist". The Age. 22 August 2002. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- ^ "Attempting to make a genomic library of an extinct animal". Australian Museum. 1999. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ "Museum ditches thylacine cloning project". ABC News Online. 15 February 2005. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ Smith, Deborah (17 February 2005). "Tassie tiger cloning 'pie-in-the-sky science'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 March 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ Skatssoon, Judy (15 February 2005). "Thylacine cloning project dumped". ABC Science Online. Archived from the original on 17 February 2005. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ "Lab takes 'giant leap' toward thylacine de-extinction with Colossal genetic engineering technology partnership" (Press release). University of Melbourne. 16 August 2022. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Morton, Adam (16 August 2022). "De-extinction: scientists are planning the multimillion-dollar resurrection of the Tasmanian tiger". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Mannix, Liam (16 August 2022). "Furry tail or fairytale? Thylacine de-extinction bid wins $10m boost, but critics question science". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ Visser, Nick (17 August 2022). "Australian Scientists Hope To 'De-Extinct' Tasmanian Tiger In Next 10 Years". HuffPost.com. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Kuta, Sarah (19 August 2022). "Why the Idea of Bringing the Tasmanian Tiger Back From Extinction Draws So Much Controversy". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (20 August 2022). "A plan to bring the Tasmanian tiger back from extinction raises questions". NPR. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Tasmanian tiger: Scientists hope to revive marsupial from extinction". 16 August 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Newton, Axel H.; Spoutil, Frantisek; Prochazka, Jan; Black, Jay R.; Medlock, Kathryn; Paddle, Robert N.; Knitlova, Marketa; Hipsley, Christy A.; Pask, Andrew J. (February 2018). "Letting the 'cat' out of the bag: pouch young development of the extinct Tasmanian tiger revealed by X-ray computed tomography". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (2): 171914. Bibcode:2018RSOS....571914N. doi:10.1098/rsos.171914. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5830782. PMID 29515893.

- ^ a b Feigin, Charles Y.; Newton, Axel H.; Doronina, Liliya; Schmitz, Jürgen; Hipsley, Christy A.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Gower, Graham; Llamas, Bastien; Soubrier, Julien; Heider, Thomas N.; Menzies, Brandon R. (11 December 2017). "Genome of the Tasmanian tiger provides insights into the evolution and demography of an extinct marsupial carnivore". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (1): 182–192. Bibcode:2017NatEE...2..182F. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0417-y. PMID 29230027.

- ^ a b c Feigin, Charles Y.; Newton, Axel H.; Pask, Andrew J. (October 2019). "Widespread cis -regulatory convergence between the extinct Tasmanian tiger and gray wolf". Genome Research. 29 (10): 1648–1658. doi:10.1101/gr.244251.118. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 6771401. PMID 31533979.

- ^ a b Newton, Axel H.; Weisbecker, Vera; Pask, Andrew J.; Hipsley, Christy A. (December 2021). "Ontogenetic origins of cranial convergence between the extinct marsupial thylacine and placental gray wolf". Communications Biology. 4 (1): 51. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-01569-x. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 7794302. PMID 33420327.

- ^ Marmol-Sanchez, Emilio; Fromm, Bastian; Oskolkov, Nikolay; Pochon, Zoe; Kalogeropoulos, Panagiotis; Eriksson, Eli; Biryukova, Inna; Sekar, Vaishnovi; Ersmark, Erik; Andersson, Bjorn; Dalen, Love; Friedlander, Marc (18 July 2023). "Historical RNA expression profiles from the extinct Tasmanian tiger". Genome Research. 33 (8): 1299–1316. doi:10.1101/gr.277663.123. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 10552650. PMID 37463752.

- ^ "MSN". www.msn.com. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ a b c "Imaging the Thylacine". University of Tasmania. 24 September 2007. Archived from the original on 16 September 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Thylacine Stamps". www.pibburns.com. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Threatened Species Day". NSW Environment & Heritage. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Hanna, Emily (5 September 2017). "National Threatened Species Day". FlagPost. Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Hart, Amalyah (4 March 2022). "Thylacine Tasmanian Tiger de-extinction". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023.

- ^ a b University Librarian (24 September 2007). "The Exotic Thylacine". Imaging the Thylacine. University of Tasmania. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ Stephens, Matthew; Williams, Robyn (13 June 2004). "John Gould's place in Australian culture". Ockham's Razor. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ^ Government Tourist Bureau, Tasmania. Tasmania: The Wonderland. Hobart: Government Printer, Tasmania, 1934

- ^ Library, University of Tasmania. "Imaging the Thylacine Exhibition – University of Tasmania Library". www.utas.edu.au. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Postage Stamp Grenada 1988. Tasmanian Tiger, Mickey Mouse and Pluto Editorial Stock Image - Image of philatelic, postal: 300086244". Dreamstime. Retrieved 2 November 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "TY the Tasmanian Tiger". Krome Studios. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Andy. "Tiny Tiger | CTR Nitro-Fueled Characters (Racers) | Crash Team Racing". Games Atlas. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Stavropoulos, Andreas (9 October 2020). "Here are all of Skye's abilities: VALORANT's upcoming agent". Dot Esports. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Wendal T. Wolf – The Internet Animation Database". www.intanibase.com. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Smith, Ian Hayden (2012). International Film Guide 2012. International Film Guide. p. 66. ISBN 978-1908215017.

- ^ "Extinct review – doughnut-shaped critters are an evolutionary dead end". the Guardian. 16 August 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Well one of Lev's hobbies is recreating such things. From their DNA". TV Fanatic. 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Bringing back the Tasmanian Tiger? New series reveals how it could be done". Southern Highland News. 30 October 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ "Thylacine". The Australian Museum. 27 January 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Thylacine Museum – Introducing the Thylacine: What is a Thylacine?". NaturalWorlds. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Giddings, Lara; Bleathman, Bill (2020) [2011]. Duretto, Marco (ed.). "Kanunnah" (PDF). The Research Journal of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. 4: 1.

- ^ "Three Capes Track" (PDF). Tacinc.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "How a vehicle testing ground became a biodiversity hotspot". Victorian National Parks Association. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Jackson Cotton, Touch the Morning: Tasmanian Native Legends (Hobart, OBM, 1979)

- ^ Penprase, Bryan (2011). The Power of Stars: How Celestial Observations Have Shaped Civilization. Springer New York. p. 73. ISBN 9781441968036.

- ^ Maynard, David (2014). "Tasmanian Tiger, Precious Little Remains". In Bienvenue, Valerie (ed.). Animals, Plants and Afterimages. Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery. ISBN 9780646919638.

Bibliography

- Owen, David (2003). Thylacine: the Tragic Tale of the Tasmanian Tiger. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-758-0.

- Paddle, Robert (2000). The Last Tasmanian Tiger: the History and Extinction of the Thylacine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53154-2.

Further reading

- Bailey, Col (2013). Shadow of the Thylacine: One Man's Epic Search for the Tasmanian Tiger. Scoresby, Vic.: Five Mile Press. ISBN 978-1-74346-485-4.

- Freeman, Carol (2010). Paper Tiger: A Visual History of the Thylacine. Human-animal studies. Leiden ; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18165-6. OCLC 643081588.

- Guiler, Eric R. (1985). Thylacine: The Tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-554603-3.

- ——; Godard, Philippe; Maguire, David (1998). Tasmanian Tiger: A Lesson to be Learnt. Perth, W.A: Abrolhos Publishng. ISBN 978-0-9585791-0-0.

- Guiler, Eric R. (1961a). "Breeding Season of the Thylacine". Journal of Mammalogy. 42 (3): 396–397. doi:10.2307/1377040. JSTOR 1377040.

- Guiler, E. R. (1961b). "The former distribution and decline of the Thylacine". Australian Journal of Science. 23 (7): 207–210.

- Heath, Alan (2014). Thylacine: Confirming Tasmanian Tigers Still Live. Chicago: Vivid Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925209-40-2.

- Leigh, Julia (1999). The Hunter. Ringwood, Australia: Penguin Books Australia. ISBN 978-0-140-28351-8.

- Lord, Clive Errol (1927). "Existing Tasmanian marsupials". Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania. 61. Royal Society of Tasmania: 17–24. doi:10.26749/GTOS1305. ISSN 0080-4703.

- Lowry, David C.; Lowry, Jacoba W. J. (January 1967). "Discovery of a Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger) Carcase In a Cave Near Eucla, Western Australia". Helictite. 5 (2): 25–29.

- Pearce, R. (1976). "Thylacines in Tasmania". Australian Mammal Society Bulletin. 3: 58.

- S., Sleightholme; N., Ayliffe (2005). International Thylacine Specimen Database (CD-ROM) (Master Copy ed.). London: Zoological Society.

- Smith, Steven J. (1981). The Tasmanian Tiger – 1980. A report on an investigation of the current status of thylacine Thylacinus cynocephalus, funded by the World Wildlife Fund Australia. Wildlife Division technical report. Hobart, Tasmania: National Parks and Wildlife Service. ISBN 978-0-724-61753-1.

External links

- The Thylacine Project Archived 26 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine at the University of New South Wales

- The Thylacine at the Australian Museum

- The Thylacine Museum at Natural Worlds

- Tasmanian tiger: newly released footage. The Guardian. 19 May 2020

- IUCN Red List extinct species

- Apex predators

- Carnivorous marsupials

- Dasyuromorphs

- Extinct mammals of Australia

- Extinct marsupials

- Holocene extinctions

- Mammal extinctions since 1500

- Mammals described in 1808

- Mammals of Tasmania

- Marsupials of Australia

- Marsupials of New Guinea

- Pleistocene first appearances

- Species made extinct by deliberate extirpation efforts

- Species that are or were threatened by climate change