Robert Bauval

Robert Bauval | |

|---|---|

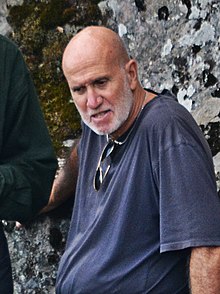

Bauval at Belintash (Bulgaria) in 2014 | |

| Born | 5 March 1948 Alexandria, Egypt |

| Occupation | Writer and lecturer |

| Education | British Boys' School |

| Alma mater | Franciscan College |

| Notable works | The Orion Mystery |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Robert Bauval (born 5 March 1948) is an Egyptian writer and lecturer, perhaps best known for the fringe Orion Correlation Theory regarding the Giza pyramid complex.

Early life

[edit]Bauval was born in Alexandria, Egypt, to parents of Belgian and Maltese origins. He attended the British Boys' School in Alexandria (now El Nasr Boys' School) and the Franciscan College in Buckinghamshire, England. He left Egypt in 1967 just before the Six-Day War, during the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser. He has spent most of his engineering career living and working in the Middle East and Africa as a construction engineer.[citation needed]

Writing career

[edit]In late 1992, Bauval had been trying to obtain a translation of Hermetica by Walter Scott. He then came across a new edition printed by Solo Press with a foreword by Adrian Gilbert.[1] Bauval contacted Gilbert after being interested in his foreword concerning a link between an Alexandrine school of Hermes Trismegistus and the pyramid builders of the Fourth dynasty of Egypt. They went on to write The Orion Mystery together, which became an international bestseller.[2] BBC Two broadcast a documentary on Bauval's ideas around the time of the book's publication.[3] He has co-authored three books with Graham Hancock, including 2004's Talisman: Sacred Cities, Secret Faith in which the two put forward what sociologist of religion David V. Barrett in a review in The Independent described as a factually incorrect and unconvincing "mess of a book" based upon indiscriminate use of source material culminating in "promulgating a version of the old Jewish-Masonic plot so beloved by ultra-right-wing conspiracy theorists.[4]

Orion Correlation Theory

[edit]

- Alnitak on the Great Pyramid of Giza

- Alnilam on the pyramid of Khafre

- Mintaka on the pyramid of Menkaure

Bauval is specifically known for the Orion Correlation Theory (OCT), which proposes a relationship between the fourth dynasty Egyptian pyramids of the Giza Plateau and the alignment of certain stars in the constellation of Orion.[5] However, 20 years before Bauval's book The Orion Mystery suggested that the Giza Pyramids were aligned to Orion's belt, James J. Hurtak pointed out such a correlation in 1973 (published in 1977).[6]

One night in 1983, while working in Saudi Arabia, he took his family and a friend's family up into the sand dunes of the Arabian Desert for a camping expedition. His friend pointed out the constellation of Orion, and mentioned that Alnitak, the most easterly of the stars making up Orion's belt, was offset slightly from the others. Bauval then made a connection between the layout of the three main stars in Orion's belt and the layout of the three main pyramids in the Giza necropolis.[7]

The Orion Correlation Theory has been described as a form of pseudoarchaeology.[8] Among the idea's critics have been two astronomers: Ed Krupp of Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, and Anthony Fairall, astronomy professor at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Krupp and Fairall independently investigated the angle between the alignment of Orion's Belt to North during the era cited by Bauval (which differs from the angle in the 3rd millennium BCE, because of the precession of the equinoxes), and found that the angle was somewhat different from the 'perfect match' claimed by Bauval and Hancock: 47 to 50 degrees, compared to the 38-degree angle formed by the pyramids.[9]

Krupp also pointed out that the slightly-bent line formed by the three pyramids was deviated towards the North, whereas the slight "kink" in the line of Orion's Belt was deformed to the South, meaning that a direct correlation would require one or the other to be inverted.[10] Indeed, this is what was done in the original book by Bauval and Gilbert (The Orion Mystery), which compared images of the pyramids and Orion without revealing that the pyramids' map had been inverted.[11] Krupp and Fairall find other problems with the claims, including the point that if the Sphinx is meant to represent the constellation of Leo, then it should be on the opposite side of the Nile (the 'Milky Way') from the pyramids ('Orion'),[9][10] that the vernal equinox around 10,500 BCE was in Virgo and not Leo,[9] and that the constellations of the Zodiac originate from Mesopotamia and were unknown in Egypt at the time.[11]

Atlantis Reborn documentary

[edit]On 4 November 1999, the BBC broadcast a documentary entitled Atlantis Reborn which tested the ideas of Robert Bauval and his colleague, Graham Hancock. Bauval and Hancock afterwards complained to the BSC (Broadcasting Standards Commission) that they had been treated unfairly. A hearing followed and in November 2000 the BSC ruled in favour of the documentary makers on all but one of the ten principal complaints brought by Hancock and Bauval.

The BSC dismissed all but one of the complaints, with the one being upheld being in respect of an omission of their rebuttal of a specific argument against the Orion Correlation Theory. In regard of the nine remaining complaints, the BSC ruled against Hancock and Bauval, concluding that they had not been treated unfairly in the criticism of their theories concerning carbon-dating, the Great Sphinx of Egypt, Cambodia's Angkor temples, Japan's Yonaguni formation and the mythical land of Atlantis.[12]

The BBC offered to broadcast a revised version of the documentary, which was welcomed by Hancock and Bauval. It was broadcast as Atlantis Reborn Again on 14 December 2000.[13] The revised documentary continued to present serious doubts about Bauval and Hancock's ideas, as held by astronomer Anthony Fairall, Ed Krupp of the Griffith Observatory, Egyptologist Kate Spence of Cambridge University and Eleanor Mannikka of the University of Michigan.[14]

Works

[edit]- The Orion Mystery (with Adrian Gilbert) (1994)

- Keeper of Genesis (with Graham Hancock) (1995)

- The Message of the Sphinx (with Graham Hancock) (May 1997)

- Secret Chamber (1999)

- Talisman: Sacred Cities, Secret Faith (with Graham Hancock) (2004)

- The Egypt Code (Oct 2006)

- Black Genesis: The Prehistoric Origins of Ancient Egypt (with Thomas Brophy PhD) (April 2011)

- The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World (Sept 2011)

- Breaking The Mirror of Heaven: The Conspiracy To Suppress The Voice of Ancient Egypt (with Ahmed Osman) (July 2012)

- Imhotep the African: Architect of the Cosmos (with Thomas Brophy) (Sept 1, 2013)

- The Vatican Heresy: Bernini and the Building of the Hermetic Temple of the Sun (with Chiara Hohenzollern and Sandro Zicari PhD) (March 2014)

- Secret Chamber Revisited: The Quest for the Lost Knowledge of Ancient Egypt (11 October 2014)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Walter Scott, Hermetica: The Ancient Greek and Latin Writings which contain Religious or Philosophic Teachings ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus (Solo Press, 1992). ISBN 1-873616-02-3

- ^ Jane Robins, Media Correspondent (22 September 2011). "'Horizon' censured for unfair treatment". The Independent.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ David Keys (21 September 2015). "EGYPTOLOGY / Trying to build heaven on earth: Controversial new". The Independent.

- ^ Barrett, David V. (18 August 2004). "Talisman: Sacred Cities, Secret Faith, by Graham Hancock & Robert Bauval". The Independent. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Fagan, Garrett G. (2006). Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. Psychology Press. pp. 38–39, 249–250. ISBN 978-0-415-30592-1.

- ^ Hurtak, James (1977). The Book of Knowledge: The Keys of Enoch. Academy for Future Science. ISBN 0960345043.

- ^ The theory, known as the Orion Correlation Theory or OCT, was first published in Discussions in Egyptology (DE, Volume 13, 1989).

- ^ Fagan, Garrett G. (2006). "Diagnosing pseudoarchaeology". In Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.). Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. Psychology Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-415-30592-1. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Fairall, Anthony (June 1999). "Precession and the layout of the Ancient Egyptian pyramids". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ a b Krupp, Ed (February 1997). "Pyramid Marketing Schemes". Sky and Telescope. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ a b Krupp, Ed (2002). "Astronomical Integrity at Giza". The Antiquity of Man. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ^ Corporation, British Broadcasting. "BBC - Science & Nature - Horizon - Atlantis Reborn Again".

- ^ Corporation, British Broadcasting. "BBC - Science & Nature - Horizon - Atlantis Reborn Again".

- ^ Corporation, British Broadcasting. "BBC - Science & Nature - Horizon - Atlantis Reborn Again".

External links

[edit]- Ed Krupp article: "Pyramid Marketing Schemes" Archived 12 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Jaromir Malek article: "Orion and the Giza pyramids" Archived 27 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- The Conscious Media Network Archived 11 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine interview with Robert Bauval (video)