Battle of Dien Bien Phu

| Battle of Dien Bien Phu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Indochina War | |||||||

French Union paratroopers dropping from a "Flying Boxcar". | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Undeclared 37 United States pilots[1] |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

As of March 13: 10,800[3] |

As of March 13: 48,000 combat personnel 15,000 logistical support personnel[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,571[5]-2,293 dead 2 dead (James B. McGovern and Wallace A. Buford) declassified in 2004[1] |

Vietnamese figures 23,000[11] | ||||||

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu (Template:Lang-fr; Template:Lang-vi) was the climactic confrontation of the First Indochina War between the French Union's French Far East Expeditionary Corps and Viet Minh communist revolutionaries. The battle occurred between March and May 1954 and culminated in a comprehensive French defeat that influenced negotiations over the future of Indochina at Geneva. Military historian Martin Windrow wrote that Điện Biên Phủ was "the first time that a non-European colonial independence movement had evolved through all the stages from guerrilla bands to a conventionally organized and equipped army able to defeat a modern Western occupier in pitched battle."[12]

As a result of blunders in the French decision-making process, the French began an operation to support the soldiers at Điện Biên Phủ, deep in the hills of northwestern Vietnam. Its purpose was to cut off Viet Minh supply lines into the neighboring Kingdom of Laos, a French ally, and tactically draw the Viet Minh into a major confrontation that would cripple them. Instead, the Viet Minh, under Senior General Võ Nguyên Giáp, surrounded and besieged the French, who were unaware of the Viet Minh's possession of heavy artillery (including anti-aircraft guns) and, more importantly, their ability to move such weapons through extremely difficult terrain to the mountain crests overlooking the French encampment. The Viet Minh occupied the highlands around Điện Biên Phủ and were able to accurately bombard French positions at will. Tenacious fighting on the ground ensued, reminiscent of the trench warfare of World War I. The French repeatedly repulsed Viet Minh assaults on their positions. Supplies and reinforcements were delivered by air, though as the French positions were overrun and the anti-aircraft fire took its toll, fewer and fewer of those supplies reached them. After a two-month siege, the garrison was overrun and most French forces surrendered, only a few successfully escaping to Laos.

Shortly after the battle, the war ended with the 1954 Geneva Accords, under which France agreed to withdraw from its former Indochinese colonies. The accords partitioned Vietnam in two; fighting later broke out between opposing Vietnamese factions in 1959, resulting in the Vietnam (Second Indochina) War.

Background and preparations

By 1953, the First Indochina War was not going well for France. A succession of commanders—Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, Jean-Étienne Valluy, Roger Blaizot, Marcel Carpentier, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, and Raoul Salan—had proven incapable of suppressing the Viet Minh insurrection. During their 1952–53 campaign, the Viet Minh had overrun vast swathes of Laos, a French ally and Vietnam's western neighbor, advancing as far as Luang Prabang and the Plain of Jars. The French were unable to slow the Viet Minh advance, and the Viet Minh fell back only after outrunning their always-tenuous supply lines. In 1953, the French had begun to strengthen their defenses in the Hanoi delta region to prepare for a series of offensives against Viet Minh staging areas in northwest Vietnam. They had set up fortified towns and outposts in the area, including Lai Chau near the Chinese border to the north,[13] Na San to the west of Hanoi,[14] and the Plain of Jars in northern Laos.[15]

In May 1953, French Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre, a trusted colleague, to take command of French Union Forces in Indochina. Mayer had given Navarre a single order—to create military conditions that would lead to an "honorable political solution."[16] On arrival, Navarre was shocked by what he found. There had been no long-range plan since de Lattre's departure. Everything was conducted on a day-to-day, reactive basis. Combat operations were undertaken only in response to enemy moves or threats. There was no comprehensive plan to develop the organization and build up the equipment of the Expeditionary force. Finally, Navarre, the intellectual, the cold and professional soldier, was shocked by the 'school's out' attitude of Salan and his senior commanders and staff officers. They were going home, not as victors or heroes, but then, not as clear losers either. To them the important thing was that they were getting out of Indochina with their reputations frayed, but intact. They gave little thought to, or concern for, the problems of their successors."[16]

Na San and the hedgehog concept

Simultaneously, Navarre had been searching for a way to stop the Viet Minh threat to Laos. Colonel Louis Berteil, commander of Mobile Group 7 and Navarre's main planner,[17] formulated the "hérisson" (hedgehog) concept. The French army would establish a fortified airhead by air-lifting soldiers adjacent to a key Viet Minh supply line to Laos.[18] This would effectively cut off Viet Minh soldiers fighting in Laos and force them to withdraw. "It was an attempt to interdict the enemy's rear area, to stop the flow of supplies and reinforcements, to establish a redoubt in the enemy's rear and disrupt his lines"[19]

The hedgehog concept was based on French experiences at the Battle of Na San. In late November and early December 1952, Giap attacked the French outpost at Na San, which was essentially an "air-land base", a fortified camp supplied only by air.[20] Giap's forces were beaten back repeatedly with very heavy losses. The French hoped that by repeating the strategy on a much larger scale, they would be able to lure Giap into committing the bulk of his forces in a massed assault. This would enable superior French artillery, armor, and air support to decimate the exposed Viet Minh forces. The experience at Na San convinced Navarre of the viability of the fortified airhead concept.

French staff officers disastrously failed to treat seriously several crucial differences between Điện Biên Phủ and Na San. First, at Na San, the French commanded most of the high ground with overwhelming artillery support.[21] At Điện Biên Phủ, however, the Viet Minh controlled much of the high ground around the valley, their artillery far exceeded French expectations and they outnumbered the French four-to-one.[3] Giap compared Điện Biên Phủ to a "rice bowl", where his troops occupied the edge and the French the bottom. Second, Giap made a mistake in Na San by committing his forces into reckless frontal attacks before being fully prepared. At Điện Biên Phủ, Giap would spend months meticulously stockpiling ammunition and emplacing heavy artillery and anti-aircraft guns before making his move. Teams of Viet Minh volunteers were sent into the French camp to scout the disposition of the French artillery. Wooden artillery pieces were built as decoys and the real guns were rotated every few salvos to confuse French counterbattery fire. As a result, when the battle finally began, the Viet Minh knew exactly where the French artillery were, while the French were not even aware of how many guns Giap possessed. Third, the aerial resupply lines at Na San were never severed despite Viet Minh anti-aircraft fire. At Điện Biên Phủ, Giap amassed anti-aircraft batteries that quickly shut down the runway and made it extremely difficult and costly for the French to bring in reinforcements.

Lead up to Castor

In June, Major General René Cogny, commander of the Tonkin Delta, proposed Điện Biên Phủ, which had an old airstrip built by the Japanese during World War II, as a "mooring point".[22] In another misunderstanding, Cogny had envisioned a lightly defended point from which to launch raids; however, to Navarre, this meant a heavily fortified base capable of withstanding a siege. Navarre selected Điện Biên Phủ for the location of Berteil's "hedgehog" operation. When presented with the plan, every major subordinate officer protested; Colonel Jean-Louis Nicot, (commander of the French Air transport fleet), Cogny, and generals Jean Gilles and Jean Dechaux (the ground and air commanders for Operation Castor, the initial airborne assault on Dien Bien Phu). Cogny pointed out, presciently, that "we are running the risk of a new Na San under worse conditions"[23] Navarre rejected the criticisms of his proposal and concluded a November 17 conference by declaring that the operation would commence three days later, on November 20, 1953.[24][25]

Navarre decided to go ahead with the operation, despite operational difficulties which would later become painfully obvious (but at the time may have been less apparent)[26] because he had been repeatedly assured by his intelligence officers that the operation had very little risk of involvement by a strong enemy force.[27] Navarre had previously considered three other ways to defend Laos: mobile warfare, which was impossible given the terrain in Vietnam; a static defense line stretching to Laos, which was not executable given the number of troops at Navarre's disposal; or placing troops in the Laotian provincial capitals and supplying them by air, which was unworkable due to the distance from Hanoi to Luang Prabang and Vientiane.[28] Thus, the only option left to Navarre was the hedgehog, which he characterized as "a mediocre solution."[29]

In a twist of fate, the French National Defense Committee ultimately agreed that Navarre's responsibility did not include defending Laos. However, their decision (which was drawn up on November 13) was not delivered to him until December 4, two weeks after the Điện Biên Phủ operation began.[30]

Establishment of the airhead

Operations at Điện Biên Phủ began at 10:35 on the morning of November 20, 1953. In Operation Castor, the French dropped or flew 9,000 troops into the area over three days. They were landed at three drop zones: Natasha, northwest of Điện Biên Phủ; Octavie, southwest of Điện Biên Phủ; and Simone, southeast of Điện Biên Phủ.[31]

The Viet Minh elite 148th Independent Infantry Regiment, headquartered at Điện Biên Phủ, reacted "instantly and effectively"; three of their four battalions, however, were absent that day.[32] Initial operations proceeded well for the French. By the end of November, six parachute battalions had been landed and the French were consolidating their positions.

It was at this time that Giap began his counter-moves. Giap had expected an attack, but could not foresee when or where it would occur. Giap realized that, if pressed, the French would abandon Lai Chau Province and fight a pitched battle at Điện Biên Phủ.[33] On November 24, Giap ordered the 148th Infantry Regiment and the 316th division to attack Lai Chau, while the 308th, 312th, and 351st divisions assault Điện Biên Phủ from Việt Bắc .[33]

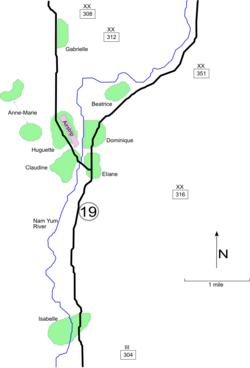

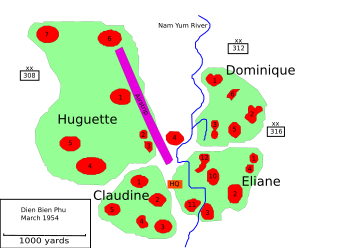

Starting in December, the French, under the command of Colonel Christian de Castries, began transforming their anchoring point into a fortress by setting up seven positions, each allegedly named after a former mistress of de Castries, although the allegation is probably unfounded, as the names simply begin with the first eight letters of the alphabet. The fortified headquarters was centrally located, with positions "Huguette" to the west, "Claudine" to the south, and "Dominique" to the northeast. Other positions were "Anne-Marie" to the northwest, "Beatrice" to the northeast, "Gabrielle" to the north and "Isabelle" four miles (6 km) to the south, covering the reserve airstrip. The choice of de Castries as the on-scene commander at Dien Bien Phu was, in retrospect, a bad one. Navarre had picked de Castries, a cavalryman in the 18th century tradition,[34] because Navarre envisioned Điện Biên Phủ as a mobile battle. In reality, Điện Biên Phủ required someone adept at World War I-style trench warfare, something for which de Castries was not suited.[35]

The arrival of the 316th Viet Minh division prompted Cogny to order the evacuation of the Lai Chau garrison to Điện Biên Phủ, exactly as Giap had anticipated. En route, they were virtually annihilated by the Viet Minh. "Of the 2,100 men who left Lai Chau on December 9, only 185 made it to Điện Biên Phủ on December 22. The rest had been killed, captured or deserted."[36] The Viet Minh troops now converged on Điện Biên Phủ.

The French had committed 10,800 troops, with more reinforcements totaling nearly 16,000 men, to the defense of a monsoon-affected valley surrounded by heavily wooded hills that had not been secured. Artillery as well as ten M24 Chaffee light tanks and numerous aircraft were committed to the garrison. The garrison comprised French regular troops (notably elite paratroop units plus artillery), Foreign Legionnaires, Algerian and Moroccan tirailleurs, and locally-recruited Indochinese infantry.

All told, the Viet Minh had moved 50,000 regular troops into the hills surrounding the valley, totaling five divisions including the 351st Heavy Division, which was made up entirely of heavy artillery.[4] Artillery and AA (anti-aircraft) guns, which outnumbered the French artillery by about four to one,[4] were moved into camouflaged positions overlooking the valley. The French came under sporadic Viet Minh artillery fire for the first time on January 31, 1954, and French patrols encountered the Viet Minh in all directions. The battle had been joined, and the French were now surrounded.

Combat operations

Beatrice

The fighting began at 5:00 PM on March 13 when the Viet Minh launched a massive surprise artillery barrage. The time and date were carefully chosen—the hour allowed the artillery to fire in daylight, and the date was chosen because it was a new moon, allowing a nighttime infantry attack.[37] The attack concentrated on position Beatrice, defended by the 3rd battalion of the 13th Foreign Legion Demi-Brigade.

Unknown to the French, the Viet Minh had made a minutely detailed study of Beatrice, and had rehearsed assaulting it using scaled models. According to one Viet Minh major: "Every evening, we came up and took the opportunity to cut barbed wire and remove mines. Our jumping-off point was moved up to only two hundred yards from the peaks of Beatrice, and to our surprise [French] artillery didn't know where we were".[38]

The French command on Beatrice was decimated at 6:15 PM when a shell hit the French command post, killing Legionnaire commander Major Paul Pegot and his entire staff. A few minutes later, Colonel Jules Gaucher, commander of the entire northern sector, was also killed by Viet Minh artillery.

The Viet Minh 312th division then launched a massive infantry assault, using sappers to defeat French obstacles. French resistance at Beatrice collapsed shortly after midnight following a fierce battle. Roughly 500 French legionnaires were killed. Viet Minh losses totalled 600 dead and 1,200 wounded.[39] The French launched a counter-attack against Beatrice the following morning, but it was quickly beaten back by Viet Minh artillery. Despite their losses, the victory at Beatrice "galvanized the morale" of the Viet Minh troops.[39]

Much to French disbelief, the Viet Minh had employed direct artillery fire, in which each gun crew does its own artillery spotting (as opposed to indirect fire, in which guns are massed farther away from the target, out of direct line of sight, and rely on a forward artillery spotter). Indirect artillery, generally held as being far superior to direct fire, requires experienced, well-trained crews and good communications which the Viet Minh lacked.[40] Navarre wrote that "Under the influence of Chinese advisers, the Viet Minh commanders had used processes quite different from the classic methods. The artillery had been dug in by single pieces... They were installed in shell-proof dugouts, and fire point-blank from portholes... This way of using artillery and AA guns was possible only with the expansive ant holes at the disposal of the Vietminh and was to make shambles of all the estimates of our own artillerymen."[41] The French artillery commander, Colonel Charles Piroth, distraught at his inability to bring counterfire on the well-camouflaged Viet Minh batteries, went into his dugout and committed suicide with a hand grenade.[42] He was buried there in secret to prevent loss of morale among the French troops.

Gabrielle

Following a four hour cease fire on the morning of March 14, Viet Minh artillery resumed pounding French positions. The air strip, already closed since 4:00 pm the day before due to a light bombardment, was now put permanently out of commission.[43] Any further French supplies would have to be delivered by parachute.[44] That night, the Viet Minh launched an attack on Gabrielle, held by an elite Algerian battalion. The attack began with a concentrated artillery barrage at 5:00 PM. Two regiments from the crack 308th division attacked starting at 8:00 PM. At 4:00 AM the following morning, a Viet Minh artillery shell hit the battalion headquarters, severely wounding the battalion commander and most of his staff.[44]

De Castries ordered a counterattack to relieve Gabrielle. However, Colonel Pierre Langlais, in forming the counterattack, chose to rely on the 5th Vietnamese Parachute battalion, which had jumped in the day before and was exhausted.[45] Although some elements of the counterattack reached Gabrielle, most were paralyzed by Viet Minh artillery and took heavy losses. At 8:00 AM the next day, the Algerian battalion fell back, abandoning Gabrielle to the Viet Minh. The French lost around 1,000 men defending Gabrielle, and the Viet Minh between 1,000-2,000.[45]

Anne-Marie

Anne - Marie was defended by T'ai troops, members of a Vietnamese ethnic minority loyal to the French. For weeks, Giap had distributed subversive propaganda leaflets, telling the T'ais that this was not their fight. The fall of Beatrice and Gabrielle had severely demoralized them. On the morning of March 17, under the cover of fog, the bulk of the T'ais left or defected. The French and the few remaining T'ais on Anne-Marie were then forced to withdraw.[46]

Lull

March 17 through March 30 saw a lull in fighting. The Viet Minh further tightened the noose around the French central area (formed by the strongpoints Huguette, Dominique, Claudine, and Eliane), effectively cutting off Isabelle and its 1,809 personnel.[47] During this lull, the French suffered from a serious crisis of command. "It had become painfully evident to the senior officers within the encircled garrison—and even to Cogny at Hanoi—that de Castries was incompetent to conduct the defense of Dien Bien Phu. Even more critical, after the fall of the northern outposts, he isolated himself in his bunker so that he had, in effect, relinquished his command authority."[48] On March 17, Cogny attempted to fly into Dien Bien Phu and take command, but his plane was driven off by anti-aircraft fire. Cogny considered parachuting into the encircled garrison, but his staff talked him out of it.[48]

De Castries' seclusion in his bunker, combined with his superiors' inability to replace him, created a leadership vacuum within the French command. On March 24, an event took place which would later become a matter of historical debate. The historian Bernard Fall records, based on Langlais' memoirs, that Colonel Langlais and his fellow paratroop commanders, all fully armed, confronted de Castries in his bunker on March 24. They told him that he would retain the appearance of command, but that Langlais would exercise it.[49] De Castries is said by Fall to have accepted the arrangement without protest, although he did exercise some command functions thereafter. Davidson states that "The truth would seem to be that Langlais did take over effective command of Dien Bien Phu, and that Castries became "commander emeritus" who transmitted messages to Hanoi and offered advise about matters in Dien Bien Phu."[50] Jules Roy, however, makes no mention of this event, and Martin Windrow argues that the 'paratrooper putsch' is unlikely to have happened. Both historians record that Langlais and Marcel Bigeard were known to be on good relations with their commanding officer.[51]

The French aerial resupply took heavy losses from Viet Minh machine guns near the landing strip. On March 27, Hanoi air transport commander Nicot ordered that all supply deliveries be made from 6,500 feet (2,000 m) or higher; losses were expected to remain heavy.[52] De Castries ordered an attack against the Viet Minh machine guns two miles (3 km) west of Dien Bien Phu. Remarkably, the attack was a complete success, with 350 Viet Minh soldiers killed and seventeen AA machine guns destroyed, while the French lost 20 killed.[53]

March 30 – April 5 assaults

The next phase of the battle saw more massed Viet Minh assaults against French positions in the central Dien Bien Phu area – at Eliane and Dominique in particular. Those two areas were held by five understrength battalions, composed of a mixture of Frenchmen, Legionnaires, Vietnamese, Africans, and T'ais.[54] Giap planned to use the tactics from the Beatrice and Gabrielle skirmishes.

At 7:00 PM on March 30, the Viet Minh 312th division captured Dominique 1 and 2, making Dominique 3 the final outpost between the Viet Minh and the French general headquarters, as well as outflanking all positions east of the river.[55] At this point, the French 4th colonial artillery regiment entered the fight, setting its 105 mm howitzers to zero elevation and firing directly on the Viet Minh attackers, blasting huge holes in their ranks. Another group of French, near the airfield, opened fire on the Viet Minh with anti-aircraft machine guns, forcing the Viet Minh to retreat.[55]

The Viet Minh were more successful in their simultaneous attacks elsewhere. The 316th division captured Eliane 1 from its Moroccan defenders, and half of Eliane 2 by midnight.[56] On the other side of Dien Bien Phu, the 308th attacked Huguette 7, and nearly succeeded in breaking through, but a French sergeant took charge of the defenders and sealed the breach.[56]

Just after midnight on the 31st, the French launched a fierce counterattack against Eliane 2, and recaptured half of it. Langlais ordered another counterattack the following afternoon against Dominique 2 and Eliane 1, using virtually "everybody left in the garrison who could be trusted to fight."[56] The counterattacks allowed the French to retake Dominique 2 and Eliane 1, but the Viet Minh launched their own renewed assault. The French, who were exhausted and without reserves, fell back from both positions late in the afternoon.[57] Reinforcements were sent north from Isabelle, but were attacked en route and fell back to Isabelle.

Shortly after dark on the 31st, Langlais told Major Marcel Bigeard, who was leading the defense at Eliane, to fall back across the river. Bigeard refused, saying "As long as I have one man alive I won't let go of Eliane 4. Otherwise, Dien Bien Phu is done for."[58] The night of the 31st, the 316th division attacked Eliane 2. Just as it appeared the French were about to be overrun, a few French tanks arrived, and helped push the Viet Minh back. Smaller attacks on Eliane 4 were also pushed back. The Viet Minh briefly captured Huguette 7, only to be pushed back by a French counterattack at dawn on the 1st.[59]

Fighting continued in this manner over the next several nights. The Viet Minh repeatedly attacked Eliane 2, only to be beaten back. Repeated attempts to reinforce the French garrison by parachute drops were made, but had to be carried out by lone planes at irregular times to avoid excessive casualties from Viet Minh anti-aircraft fire.[59] Some reinforcements did arrive, but not nearly enough to replace French casualties.

Trench warfare

On April 5, after a long night of battle, French fighter-bombers and artillery inflicted particularly devastating losses on one Viet Minh regiment which was caught on open ground. At that point, Giap decided to change tactics. Although Giap still had the same objective – to overrun French defenses east of the river – he decided to employ entrenchment and sapping to try to achieve it.[60]

April 10 saw the French attempt to retake Eliane 1. The loss of Eliane 1 eleven days earlier had posed a significant threat to Eliane 4, and the French wanted to eliminate that threat. The dawn attack, which Bigeard devised, was preceded by a short, massive artillery barrage, followed by small unit infiltration attacks, followed by mopping-up operations. Eliane 1 changed hands several times that day, but by the next morning the French had control of the strongpoint. The Viet Minh attempted to retake it on the evening of April 12, but were pushed back.[61]

At this point, the morale of the Viet Minh soldiers was greatly lowered. During the stalemate, the French intercepted enemy radio messages which told of whole units refusing orders to attack, and Communist prisoners said that they were told to advance or be shot by the officers and noncommissioned officers behind them.[62] Worse still, the Viet Minh lacked advanced medical care, with one stating that "Nothing strikes at combat morale like the knowledge that if wounded, the soldier will go uncared for."[63] To avert the crisis, Giap called in fresh reinforcements from Laos.

During the fighting at Eliane 1, on the other side of camp, the Viet Minh entrenchments had almost entirely surrounded Huguette 1 and 6. On April 11, the garrison of Huguette 1 attacked, and was joined by artillery from the garrison of Claudine. The goal was to resupply Huguette 6 with water and ammunition. The attacks were repeated on the night of the 14–15th and 16–17th. While they did succeed in getting some supplies through, the French suffered heavy casualties, which convinced Langlais to abandon Huguette 6. Following a failed attempt to link up, on April 18, the defenders at Huguette 6 made a daring break out, but only a few managed to make it to French lines.[64][65] The Viet Minh repeated the isolation and probing attacks against Huguette 1, and overran the fort on the morning of April 22. With the fall of Huguette 1, the Viet Minh took control of more than 90% of the airfield, making accurate parachute drops impossible.[66] This caused the landing zone to become perilously small, and effectively choked off much needed supplies.[67] A French attack against Huguette 1 later that day was repulsed.

Isabelle

Isabelle saw only desultory action until March 30, when the Viet Minh succeeded in isolating it and beating back the attempt to send reinforcements north. Following a massive artillery barrage against Isabelle on March 30, the Viet Minh began employing the same trench warfare tactics against Isabelle that they were using against the central camp. By the end of April, Isabelle had exhausted its water supply and was nearly out of ammunition.[68]

Final attacks

The Viet Minh launched a massed assault against the exhausted defenders on the night of May 1, overrunning Eliane 1, Dominique 3, and Huguette 5, although the French managed to beat back attacks on Eliane 2. On May 6, the Viet Minh launched another massed attack against Eliane 2. The attack included, for the first time, Katyusha rockets.[39] The French also used an innovation. The French artillery fired with a "TOT" (Time On Target) attack, so that artillery rounds fired from different positions would strike on target at the same time.[69] The barrage decimated the first assault wave. A few hours later that night, the Viet Minh detonated a mine shaft, blowing Eliane 2 up. The Viet Minh attacked again, and within a few hours had overrun the defenders.[70]

On May 7, Giap ordered an all out attack against the remaining French units with over 25,000 Viet Minh against fewer than 3,000 garrison troops. At 5:00 PM, de Castries radioed French headquarters in Hanoi and talked with Cogny.

De Castries: "The Viets are everywhere. The situation is very grave. The combat is confused and goes on all about. I feel the end is approaching, but we will fight to the finish."

Cogny: "Of course you will fight to the end. It is out of the question to run up the white flag after your heroic resistance."[34]

By nightfall, all French central positions had been captured. The last radio transmission from the French headquarters reported that enemy troops were directly outside the headquarters bunker and that all the positions have been overrun. The radio operator in his last words stated: "The enemy has overrun us. We are blowing up everything. Vive la France!" That night, the garrison at Isabelle made a breakout attempt. While the main body did not even escape the valley, about 70 troops out of 1,700 men in the garrison did escape to Laos.[71]

Aftermath

Prisoners

On May 8, the Viet Minh counted 11,721 prisoners, of whom 4,436 were wounded.[72] This was the greatest number the Viet Minh had ever captured: one-third of the total captured during the entire war. The prisoners were divided into groups. Able bodied soldiers were force-marched over 250 miles (400 km) to prison camps to the north and east,[73] where they were intermingled with Viet Minh soldiers to discourage French bombing runs.[74] Hundreds died of disease on the way. The wounded were given basic first aid until the Red Cross arrived, removed 858, and provided better aid to the remainder. Those wounded who were not evacuated by the Red Cross were sent into detention.[75]

The prisoners, French survivors of the battle at Dien Bien Phu, were starved, beaten, and heaped with abuse, and many died.[76] Of 10,863 survivors held as prisoners, only 3,290 were officially repatriated four months later.[72] However, the losses figure may include the 3,013 prisoners of Vietnamese origin whose eventual fate is unknown.[77]

Political ramifications

The garrison constituted roughly a tenth of the total French Union manpower in Indochina.[78] The defeat seriously weakened the position and prestige of the French as previously planned negotiations over the future of Indochina began.

The Geneva Conference (1954) opened on May 8, the day after the surrender of the garrison. Ho Chi Minh entered the conference on the opening day with the news of his troops' victory in the headlines. The resulting agreement temporarily partitioned Vietnam into two zones: the North was administered by the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam while the South was administered by the French-supported State of Vietnam. The last units of the French Union forces withdrew from Indo-China in 1956. This partition was supposed to be temporary, and the two zones were meant to be reunited through national elections in 1956. After the French withdrawal, the United States supported the southern government, under Emperor Bảo Đại and Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem, which opposed the Geneva agreement, and which claimed that Ho Chi Minh's forces from the North had been killing Northern patriots and terrorizing people both in the North and the South. The North was supported by both communist China and the Soviet Union. This arrangement proved tenuous and would escalate into the Vietnam War (Second Indochina War), eventually bringing 500,000 American troops to defend South Vietnam.

France's defeat in Indochina, coupled with the German destruction of her armies just 14 years earlier, seriously damaged its prestige elsewhere in their colonial empire, as well as with its NATO allies, most importantly, the United States. Within her empire, the defeat in Indochina served to spur independence movements in other colonies, notably the North African territories from which many of the troops who fought at Dien Bien Phu had been recruited. In 1954, six months after the battle at Dien Bien Phu ended, the Algerian War started, and by 1956 both Moroccan and Tunisian protectorates had gained independence. A French board of inquiry, the Catroux Commission, would later investigate the defeat.

The battle was depicted in Dien Bien Phu, a 1992 docudrama film – with several autobiographical parts – in conjunction with the Vietnamese army by Dien Bien Phu veteran French director Pierre Schoendoerffer.

American participation

According to the Mutual Defense Assistance Act the United States provided the French with material aid during the battle – aircraft (supplied by the USS Saipan), weapons, mechanics, 24 CIA/CAT pilots, and U.S. Air Force maintenance crews.[79] The United States, however, intentionally avoided overt direct intervention. In February 1954, following French occupation of Dien Bien Phu but prior to the battle, Democratic senator Mike Mansfield asked United States Defense Secretary Charles Erwin Wilson whether the United States would send naval or air units if the French were subjected to greater pressure there, but Wilson replied that "for the moment there is no justification for raising United States aid above its present level". President Dwight D. Eisenhower also stated, "Nobody is more opposed to intervention than I am".[79] On March 31, following the fall of Beatrice, Gabrielle, and Anne-Marie, a panel of U.S. Senators and House Representatives questioned the American Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Arthur W. Radford, about the possibility of American involvement. Radford concluded that it was too late for the U.S. Air Force to save the French garrison. A proposal for direct intervention was unanimously voted down by the panel, which "concluded that intervention was a positive act of war".[80]

The United States did covertly participate in the battle. Following a request for help from Henri Navarre, Radford provided two squadrons of B-26 Invader bomber aircraft to support the French. Subsequently, 37 American transport pilots flew 682 sorties over the course of the battle.[81] Earlier, in order to succeed the pre-Dien Bien Phu Operation Castor of November 1953, General Chester McCarty made available 12 additional C-119 Flying Boxcars flown by French crews.[81] Two of the American pilots, Wallace Buford and James McGovern, Jr., were killed in action during the siege of Dien Bien Phu.[82] On February 25, 2005, the seven still living American pilots were awarded the French Legion of Honor by Jean-David Levitte, the French ambassador to the United States.[81] The role that the American pilots played in this battle had remained little known until 2004. The "American historian Erik Kirsinger researched the case for more than a year to establish the facts."[83][84] The French author Jules Roy also suggests that Admiral Radford discussed with the French the possibility of using nuclear weapons in support of the French garrison.[85] Moreover, John Foster Dulles was reported to have mentioned the possibility of lending atomic bombs to the French for use at Dien Bien Phu,[86] and a similar source claims that British Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden was aware of the possibility of the use of nuclear weapons in that region.[87]

Khe Sanh

In January 1968, during the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese Army (still under Giap's command) made an apparent attempt to repeat their success at Dien Bien Phu, by a siege and artillery bombardment on the U.S. Marine Corps infantry and artillery base at Khe Sanh, South Vietnam. Historians are divided on whether this was a genuine attempt to force the surrender of that Marine base, or else a diversion from the rest of the Tet Offensive, or an example of the North Vietnamese Army keeping its options open.

At Khe Sanh, a number of factors were significantly different from the siege of Dien Bien Phu. Khe Sanh was much closer to an American supply base (45 km (28 mi)*) compared to a French one at Dien Bien Phu (200 km (120 mi)*).[88]

At Khe Sanh, the U.S. Marines held the high ground, and their artillery forced the North Vietnamese to use their own artillery from a much greater distance. By contrast, at Dien Bien Phu, the French artillery (six 105 mm batteries and one battery of four 155 mm howitzers and mortars[89]) were only sporadically effective;[90] Khe Sanh received 18,000 tons in aerial resupplies during the 30-day battle, whereas during 167 days that the French forces at Dien Bien Phu held out, they received only 4,000 tons.[90] By the end of the battle of Khe Sanh, U.S. Air Force planes had flown 9,691 tactical sorties and dropped 14,223 tons of munitions on targets within the Khe Sanh area. U.S. Marine Corps planes had flown 7,098 missions and dropped 17,015 tons of munitions. U.S. Navy planes, many of which had been redirected from the Operation Rolling Thunder bombing campaign against North Vietnam, flew 5,337 sorties and dropped 7,941 tons of ordnance on the enemy.

French women at Dien Bien Phu

Many of the flights operated by the French Air force to evacuate casualties had female flight nurses on board. A total of 15 women served on flights to Dien Bien Phu. One of them, Geneviève de Galard, was stranded at Dien Bien Phu when her plane was destroyed by shellfire while being repaired on the airfield. She remained on the ground providing medical services in the field hospital until the surrender. She was later referred to as the "Angel of Dien Bien Phu". However historians disagree regarding this moniker, with Martin Windrow maintaining that Galard was referred to by this name by the garrison itself, but Michael Kenney maintaining that it was added by outside press agencies.[91]

The French forces came to Dien Bien Phu accompanied by two "Bordels Mobiles de Campagne", (mobile field brothels), served by Algerian and Vietnamese women.[92] When the siege ended, the Vietminh sent the surviving Vietnamese women for "re-education."[93]

See also

- Siege of Bangkok, 1688 – battle marking end of French military in Siam (present-day Thailand)

Notes

- ^ a b French Ambassy in the United States: News from France 05.02 (March 2, 2005), U.S. pilots honored for Indochina Service, Seven American Pilots were awarded the Legion of Honor...

- ^ Xiaobing Li (2007). A history of the modern Chinese Army. University Press of Kentucky. p. 212. ISBN 0-8131-2438-7.

- ^ a b Davidson, 224

- ^ a b c Davidson, 223

- ^ Lam Quang Thi, Andrew Wiest Hell in An Loc: The 1972 Easter Invasion University of North Texas Press (2009), p.14

- ^ Lam Quang Thi, p.14

- ^ Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, trang 62, Indiana University Press

- ^ French Defense Ministry's archives, ECPAD

- ^ http://www.voanews.com/vietnamese/archive/2004-05/a-2004-05-07-30-1.cfm

- ^ Ban tổng kết-biên soạn lịch sử, BTTM (1991). Lịch sử Bộ Tổng tham mưu trong kháng chiến chống Pháp 1945-1954. Ha Noi: Nhà xuất bản Quân Đội Nhân Dân. p. 799. (History Study Board of The General Staff (1991). History of the General Staff in the Resistance War against the French 1945-1954 (in Vietnamese). Ha Noi: People's Army Publishing House. p. 799.).

- ^ Stone, 109

- ^ Quotation from Martin Windrow. Kenney, Michael. "British Historian Takes a Brilliant Look at French Fall in Vietnam". Boston Globe, January 4, 2005.

- ^ Fall, 23

- ^ Fall, 9

- ^ Fall, 48

- ^ a b Davidson, 165

- ^ Fall, 44

- ^ Davidson, 173

- ^ Bruce Kennedy. CNN Cold War Special: 1954 battle changed Vietnam's history

- ^ Fall, 24

- ^ Davidson, 147

- ^ Davidson, 182

- ^ Roy, 21

- ^ Roy, 33

- ^ Davidson, 184

- ^ Windrow, p211, 212, 228, 275

- ^ Davidson, 189

- ^ Davidson, 186

- ^ Davidson, 187

- ^ Davidson, 176

- ^ Davidson, 194

- ^ Davidson, 193

- ^ a b Davidson, 196

- ^ a b "The Fall of Dienbienphu". Time. 1954-05-17.

- ^ Davidson, 199

- ^ Davidson, 203

- ^ Davidson, 234

- ^ Roy, 167

- ^ a b c Davidson, 236

- ^ Davidson, 227

- ^ Navarre, 225

- ^ "Dien Bien Phu". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ Dien Bien Phu: the epic battle America forgot By Howard R. Simpson

- ^ a b Davidson, 237

- ^ a b Davidson, 238

- ^ Davidson, 239

- ^ Fall, 279

- ^ a b Davidson, 240–241

- ^ Fall, 177

- ^ Davidson, 243

- ^ Windrow, p. 441-444.

- ^ Davidson, 244

- ^ Davidson, 244–245

- ^ Davidson, 245

- ^ a b Davidson, 246

- ^ a b c Davidson, 247

- ^ Davidson, 248

- ^ Roy, 210

- ^ a b Davidson, 253

- ^ Davidson, 254–255

- ^ Davidson, 265

- ^ Davidson, 256

- ^ Davidson, 257

- ^ Davidson, 258

- ^ Fall, 260

- ^ Fall, 270

- ^ Davidson, 259

- ^ Davidson, 260

- ^ Davidson, 261

- ^ Davidson, 262

- ^ Davidson, 269

- ^ a b "Breakdown of losses suffered at Dien Bien Phu". dienbienphu.org. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ "The Long March". dienbienphu.org. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ Fall, 429

- ^ The Long March. Dienbienphu.org, Retrieved on January 12, 2009

- ^ "At camp #1". dienbienphu.org. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Arzalier, Les Pertes Humaines, 1954–2004: La Bataille de Dien Bien Phu, entre Histoire et Mémoire, Société française d'histoire d'outre-mer, 2004

- ^ "The French Far East Expeditionary Corps numbered 175,000 soldiers" – Davidson, 163

- ^ a b Roy, 140

- ^ Roy, 211

- ^ a b c Embassy of France in the USA, Feb. 25, 2005, U.S. Pilots Honored For Indochina Service

- ^ Check-Six.com - The Shootdown of "Earthquake McGoon"

- ^ "France honors U.S. pilots for Dien Bien Phu role". Agence France Presse. February 25, 2005.

- ^ Burns, Robert. "Covert U.S. aviators will get French award for heroism in epic Asian battle". Associated Press Worldstream. February 16, 2005

- ^ Roy, 198

- ^ Fall, 306

- ^ Fall, 307

- ^ Rottman, 8

- ^ Fall, 480

- ^ a b Rottman, 9

- ^ Fall, 190

- ^ Windrow P673, Note 53

- ^ Pringle, James (1 April 2004). "Au revoir, Dien Bien Phu". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008..

References

- Davidson, Phillip (1988). Vietnam at War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506792-4.

- "Dien Bien Phu". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- "Ðiên Biên Phú – The "official and historical site" of the battle". Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Fall, Bernard B. (1967). Hell in a Very Small Place. The Siege of Dien Bien Phu. New York: J.B. Lippincott Company. ISBN 0-306-80231-7.

- "The Fall of Dienbienphu". Time. 1954-05-17.

- Navarre, Henri (1958). Agonie de l'Indochine (in French). Paris: Plon. OCLC 23431451.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Khe Sanh (1967–1968) – Marines battle for Vietnam's vital hilltop base. Oxford: Osprey Publishing (UK). ISBN 1-84176-863-4.

- Roy, Jules. The Battle of Dienbienphu. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-88184-034-3. OCLC 263986.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Roy, Jules (2002). The Battle of Dienbienphu. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-0958-8.

- Stone, David (2004). Dien Bien Phu. London: Brassey's UK. ISBN 1-85753-372-0.

- Windrow, Martin (2004). The Last Valley. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81386-6.

External links

- Dien Bien Phu Site dedicated to the battle.

- Memorial-Indochine.org in English

- An Analysis of the French Defeat at Dien Bien Phu

- Airlift's Role at Dien Bien Phu and Khe Sanh

- An interview with Vo Nguyen Giap

- Battle of Dien Bien Phu, an article by Bernard B. Fall

- Dien Bien Phu: A Battle Assessment by David Pennington

- "Peace" in a Very Small Place: Dien Bien Phu 50 Years Later by Bob Seals

- ANAPI's official website (National Association of Former POWs in Indochina)

- Bibliography: Dien Bien Phu and the Geneva Conference

Media links

- Newsreels (video)

- Template:En icon The News Magazine of the Screen (May 1954)

- Template:En icon U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles on the fall of Dien Bien Phu (May 7th, 1954)

- Template:En icon Dien Bien Phu Episode From Ten Thousand Day War Documentary

- Retrospectives (video)

- Template:En icon English subtitled (Closed Captions) scene from the "Dien Bien Phu" docudrama by Schoendoerffer (1992)

- Template:En icon Archive footages of Colonel Sassi and his 2,000 strong Hmong partisans en route to Dien Bien Phu for a rescue mission in April 1954 (2000)

- Template:Fr icon Archive radio calls between General Cogny & Colonel de Castries (1954) + 2 commented scenes from Schoendoerffer's docudrama (1992)

- Template:Fr icon Testimonial of General Giap, 50 years after the battle (May 7th, 2004)

- Template:Fr icon Testimonial of General Bigeard, 50 years after the battle (May 3rd, 2004)

- Template:Fr icon Testimonial of Corporal Schoendoerffer, 50 years after the battle (May 5th, 2004)

- War reports (Picture galleries and captions)