Bee Gees

Bee Gees | |

|---|---|

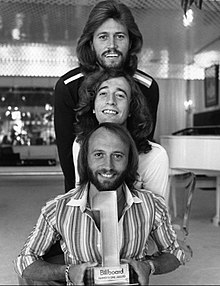

The Bee Gees in 1977 (top to bottom): Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | BGs (1958–1959) |

| Genres | |

| Discography | Bee Gees discography |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Past members | Barry Gibb Robin Gibb Maurice Gibb Vince Melouney Colin Petersen[2][3] Geoff Bridgford |

| Website | beegees |

The Bee Gees were a musical group formed in 1958 by brothers Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb. The trio were especially successful in popular music in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and later as prominent performers in the disco music era in the mid-to-late 1970s. The group sang recognisable three-part tight harmonies: Robin's clear vibrato lead vocals were a hallmark of their earlier hits, while Barry's R&B falsetto became their signature sound during the mid-to-late 1970s and 1980s. The group wrote all their own original material, as well as writing and producing several major hits for other artists, and are regarded as one of the most important and influential acts in pop-music history.[4] They have been referred to in the media as The Disco Kings, Britain's First Family of Harmony, and The Kings of Dance Music.[5][6][7]

Born on the Isle of Man to English parents, the Gibb brothers lived in Chorlton, Manchester, England, until the late 1950s. There, in 1955, they formed the skiffle/rock and roll group the Rattlesnakes. The family then moved to Redcliffe, in the Moreton Bay Region, Queensland, Australia, and later to Cribb Island. After achieving their first chart successes in Australia as the Bee Gees, they returned to the UK in January 1967, when producer Robert Stigwood began promoting them to a worldwide audience. The Bee Gees' Saturday Night Fever soundtrack (1977) was the turning point of their career, with both the film and soundtrack having a cultural impact throughout the world, enhancing the disco scene's mainstream appeal. They won five Grammy Awards for Saturday Night Fever, including Album of the Year.

The Bee Gees have sold over 120 million records worldwide,[8][9][10] placing them among the best-selling music artists of all time, as well as the most successful trio in the history of contemporary music.[11] They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997;[12] the Hall's citation says, "Only Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Michael Jackson, Garth Brooks and Paul McCartney have outsold the Bee Gees."[13] With nine number-one hits on the Billboard Hot 100, the Bee Gees are the third-most successful band in Billboard charts history behind only the Beatles and the Supremes.[14] Following Maurice's sudden death in 2003 aged 53, Barry and Robin retired from the group after 45 years of activity. However, in 2009 Robin announced that he and Barry had agreed the Bee Gees would re-form and perform again.[15] Robin died in 2012, aged 62, and Colin Petersen died in 2024, aged 78, leaving Barry, Vince Melouney, and Geoff Bridgford as the surviving members of the group.[16]

History

[edit]1955–1966: Music origins, Bee Gees formation and popularity in Australia

[edit]

Born on the Isle of Man during the late 1940s, the Gibb brothers moved to their father Hugh Gibb's home town Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester, England, in 1955. They formed a skiffle/rock-and-roll group, the Rattlesnakes, which consisted of Barry on guitar and vocals, Robin and Maurice on vocals, and friends Paul Frost on drums and Kenny Horrocks on tea-chest bass. In December 1957, the boys began to sing in harmony. The story is told that they were going to lip-sync to a record in the local Gaumont cinema (as other children had done on previous weeks), but, as they were running to the theatre, the fragile shellac 78-RPM record broke. The brothers had to sing live but received such a positive response from the audience that they decided to pursue a singing career.[17] In May 1958, the Rattlesnakes disbanded when Frost and Horrocks left, so the Gibb brothers then formed Wee Johnny Hayes and the Blue Cats, with Barry as "Johnny Hayes".[18]

In August 1958, the Gibb family, including older sister Lesley and infant brother Andy (born in March 1958), emigrated to Australia and settled in Redcliffe, Queensland, just north-east of Brisbane. The young brothers began performing to raise pocket money. Speedway promoter and driver Bill Goode, who had hired the brothers to entertain the crowd at the Redcliffe Speedway in 1960, introduced them to Brisbane radio-presenter jockey Bill Gates. The crowd at the speedway would throw money onto the track for the boys, who generally performed during the interval of meetings (usually on the back of a truck that drove around the track) and, in a deal with Goode, any money they collected from the crowd they were allowed to keep. Gates named the group the "BGs" (later changed to "Bee Gees") after his, Goode's and Barry Gibb's initials. The name was not specifically a reference to "Brothers Gibb", despite popular belief.[19][20][21]

During the next few years, they began working regularly at resorts on the Queensland coast. Through his songwriting, Barry sparked the interest of Australian star Col Joye, who helped the brothers get a recording deal in 1963 with Festival Records subsidiary Leedon Records under the name "Bee Gees". The three released two or three singles a year, while Barry supplied additional songs to other Australian artists. In 1962 the Bee Gees were chosen as the supporting act for Chubby Checker's concert at the Sydney Stadium.[22]

From 1963 to 1966, the Gibb family lived at 171 Bunnerong Road, Maroubra, in Sydney.[23] Just before his death, Robin Gibb recorded the song "Sydney" about the brothers' experience of living in that city. It was released on his posthumous album 50 St. Catherine's Drive.[24] The house was demolished in 2016.[25]

A minor hit in 1965, "Wine and Women", led to the group's first LP, The Bee Gees Sing and Play 14 Barry Gibb Songs. By 1966 Festival Records was, however, on the verge of dropping them from the Leedon roster because of their perceived lack of commercial success. At this time the brothers met the American-born songwriter, producer, and entrepreneur Nat Kipner, who had just been appointed A&R manager of a new independent label, Spin Records. Kipner briefly took over as the group's manager and successfully negotiated their transfer to Spin in exchange for granting Festival the Australian distribution rights to the group's recordings.[26] Through Kipner the Bee Gees met engineer-producer, Ossie Byrne, who produced (or co-produced with Kipner) many of the earlier Spin recordings, most of which were cut at his own small, self-built St Clair Studio in the Sydney suburb of Hurstville. Byrne gave the Gibb brothers virtually unlimited access to St Clair Studio over a period of several months in mid-1966.[27] The group later acknowledged that this enabled them to significantly improve their skills as recording artists. During this productive time, they recorded a large batch of original material—including the song that became their first major hit, "Spicks and Specks" (on which Byrne played the trumpet coda)—as well as cover versions of current hits by overseas acts such as the Beatles. They regularly collaborated with other local musicians, including members of beat band Steve & The Board, led by Steve Kipner, Nat's teenage son.[28]

Frustrated by their lack of success, the Gibbs began their return journey to England on 4 January 1967, with Ossie Byrne travelling with them. While at sea in January 1967, the Gibbs learned that Go-Set, Australia's most popular and influential music newspaper, had declared "Spicks and Specks" the "Best Single of the Year".[29]

1967–1969: International fame and touring years

[edit]Bee Gees' 1st, Horizontal and Idea

[edit]

Before their departure from Australia to England, Hugh Gibb sent demos to Brian Epstein, who managed the Beatles and directed NEMS, a British music store. Epstein passed the demo tapes to Robert Stigwood, who had recently joined NEMS.[30] After an audition with Stigwood in February 1967, the Bee Gees signed a five-year contract whereby Polydor Records would release their records in the UK, and Atco Records would do so in the US. Work quickly began on the group's first international album, and Stigwood launched a promotional campaign to coincide with its release.[31]

Stigwood proclaimed that the Bee Gees were "The most significant new musical talent of 1967", thus initiating the comparison of the Bee Gees to the Beatles. Before recording the first album, the group expanded to include Colin Petersen and Vince Melouney.[32] "New York Mining Disaster 1941", their second British single (their first-issued UK 45 rpm was "Spicks and Specks"), was issued to radio stations with a blank white label listing only the song title. Some DJs immediately assumed this was a new single by the Beatles and started playing the song in heavy rotation. This helped the song climb into the top 20 in both the UK and US.[33]

No such chicanery was needed to boost the Bee Gees' next single, "To Love Somebody", into the US Top 20. Originally written for Otis Redding, "To Love Somebody", a soulful ballad sung by Barry, has since become a pop standard recorded by many singers.[34] Another single, "Holiday", released in the US, peaked at No. 16.[35]

The parent album, Bee Gees 1st (their first internationally), peaked at No. 7 in the US and No. 8 in the UK. Bill Shepherd was credited as the arranger. After recording that album, the group recorded their first BBC session at the Playhouse Theatre, Northumberland Avenue, in London, with Bill Bebb as the producer, and they performed three songs. That session is included on BBC Sessions: 1967–1973 (2008).[36] After the release of Bee Gees' 1st, the group was first introduced in New York as "the English surprise".[37] At that time, the band made their first British TV appearance on Top of the Pops. Maurice recalled:

Jimmy Savile was on it and that was amazing because we'd seen pictures of him in the Beatles fan club book, so we thought we were really there! That show had Lulu, us, the Move, and the Stones doing 'Let's Spend the Night Together'. You have to remember this was really before the superstar was invented so you were all in it together.[38]

In late 1967, they began recording their second album. On 21 December 1967, in a live broadcast from Liverpool Anglican Cathedral for a Christmas television special called How On Earth?, they performed their own song, "Thank You For Christmas" which was written especially for the programme, as well as a medley of the traditional Christmas carols "Silent Night", "The First Noel" and "Mary's Boy Child" (the latter incorrectly noted as "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing" on tape boxes and subsequent release). The songs were all pre-recorded on 1 December 1967 and the group lip-synched their performance. The recordings were eventually released on the "Horizontal" reissue bonus disc in 2008. The folk group the Settlers and Radio 1 disc-jockey, Kenny Everett, also performed on the programme, which was presented by the Reverend Edward H. Patey, dean of the cathedral.[39]

January 1968 began with a promotional trip to the US. Los Angeles Police were on alert in anticipation of a Beatles-type reception, and special security arrangements were being put in place.[32] In February, Horizontal repeated the success of their first album, featuring the group's first UK No. 1 single "Massachusetts" (a No. 11 US hit) and the No. 7 UK single "World".[40] The sound of the album Horizontal had a more "rock" sound than their previous release, although ballads like "And the Sun Will Shine" and "Really and Sincerely" were included. The Horizontal album reached No. 12 in the US and No. 16 in the UK.[41]

With the release of Horizontal, they also embarked on a Scandinavian tour with concerts in Copenhagen. Around the same time, the Bee Gees turned down an offer to write and perform the soundtrack for the film Wonderwall, according to director Joe Massot.[38]

On 27 February 1968, the band, backed by the 17-piece Massachusetts String Orchestra, began their first tour of Germany with two concerts at Hamburg Musikhalle. In March 1968, the band was supported by Procol Harum (who had a hit "A Whiter Shade of Pale") on their German tour.[42] As Robin's partner Molly Hullis recalls: "Germans were wilder than the fans in England at the heights of Beatlemania." The tour schedule took them to 11 venues in as many days with 18 concerts played, finishing with a brace of shows at the Stadthalle, Braunschweig.

After that, the group was off to Switzerland. As Maurice described it:

There were over 5,000 kids at the airport in Zurich. The entire ride to Bern, the kids were waving Union Jacks. When we got to the hotel, the police weren't there to meet us and the kids crushed the car. We were inside and the windows were all getting smashed in, and we were on the floor.[38]

On 17 March, the band performed "Words" on The Ed Sullivan Show. The other artists who performed on that night's show were Lucille Ball, George Hamilton and Fran Jeffries.[43] On 27 March 1968, the band performed at the Royal Albert Hall in London.[38]

Two more singles followed in early 1968: the ballad "Words" (No. 8 UK, No. 15 US) and the double A-sided single "Jumbo" backed with "The Singer Sang His Song". "Jumbo" only reached No. 25 in the UK and No. 57 in the US. The Bee Gees felt "The Singer Sang His Song" was the stronger of the two sides, an opinion shared by listeners in the Netherlands who made it a No. 3 hit.[citation needed]

Further Bee Gees chart singles followed: "I've Gotta Get a Message to You", their second UK No. 1 (No. 8 US), and "I Started a Joke" (No. 6 US), both culled from the band's third album Idea.[40] Idea reached No. 4 in the UK and was another top 20 album in the US (No. 17).[40]

After the tour and TV special to promote the album, Vince Melouney left the group, desiring to play more of a blues style music than the Gibbs were writing. Melouney did achieve one feat while with the Bee Gees: his "Such a Shame" (from Idea) is the only song on any Bee Gees album not written by a Gibb brother.[citation needed]

The band were due to begin a seven-week tour of the US on 2 August 1968, but on 27 July, Robin collapsed and fell unconscious. He was admitted to a London nursing home for nervous exhaustion, and the American tour was postponed.[38] The band began recording their sixth album, which resulted in their spending a week recording at Atlantic Studios in New York. Robin, still feeling poorly, missed the New York sessions, but the rest of the band put away instrumental tracks and demos.[44]

Odessa, Cucumber Castle and break-up

[edit]

By 1969, Robin began to feel that Stigwood had been favouring Barry as the frontman.[45]

The Bee Gees' performances in early 1969 on the Top of the Pops and The Tom Jones Show, singing "I Started a Joke" and "First of May" as a medley, were the final appearances of the group with Robin.[46]

Their next album, which was to have been a concept album called Masterpeace, evolved into the double-album Odessa. Most rock critics felt this was the best Bee Gees album of the 1960s with its progressive rock feel on the title track, the country-flavoured "Marley Purt Drive" and "Give Your Best", and ballads such as "Melody Fair" and "First of May" (the last of which became the only single from the album and a UK # 6 hit). Feeling the flipside, "Lamplight", should have been the A-side, Robin quit the group in mid-1969 and launched a solo career.[47]

The first of many Bee Gees compilations, Best of Bee Gees, was released featuring the non-LP single "Words" plus the Australian hit "Spicks and Specks". The single "Tomorrow Tomorrow" was also released and was a moderate hit in the UK, where it reached No. 23, but it was only No. 54 in the US. The compilation reached the top 10 in both the UK and the US.[40]

While Robin pursued his solo career, Barry, Maurice and Petersen continued as the Bee Gees on their next album, Cucumber Castle. The band made their debut performance without Robin at Talk of the Town. They had recruited their sister, Lesley, to participate in at least one performance at this time as a replacement for Robin.[48] To accompany the album, they also filmed a TV special with Frankie Howerd and cameos from several other contemporary pop and rock stars, which aired on the BBC in December 1970. Petersen played drums on the tracks recorded for the album but was fired from the group after filming began (he went on to form the Humpy Bong with Jonathan Kelly). His parts were edited out of the final cut of the film and Pentangle drummer Terry Cox was recruited to complete the recording of songs for the album.[49][50]

After the album was released in early 1970, it seemed that the Bee Gees were finished. The leadoff single, "Don't Forget to Remember", was a big hit in the UK, reaching No. 2, but only reached No. 73 in the US. The next two singles, "I.O.I.O." and "If I Only Had My Mind on Something Else", barely scraped the charts. On 1 December 1969, Barry and Maurice parted ways professionally.[51]

Maurice started to record his first solo album, The Loner, which was not released. Meanwhile, he released the single "Railroad" and starred in the West End musical Sing a Rude Song.[52] In February 1970, Barry recorded a solo album which never saw official release either, although "I'll Kiss Your Memory" was released as a single backed by "This Time" without much interest.[53] Meanwhile, Robin saw chart success in Europe and Australia with his UK No. 2 hit "Saved by the Bell" from the album Robin's Reign.[54]

1970–1974: Reformation

[edit]

In mid 1970, according to Barry, "Robin rang me in Spain where I was on holiday [saying] 'let's do it again'". By 21 August 1970, after they had reunited, Barry announced that the Bee Gees "are there and they will never, ever part again". Maurice said, "We just discussed it and re-formed. We want to apologise publicly to Robin for the things that have been said."[18] Earlier, in June 1970, Robin and Maurice recorded a dozen songs before Barry joined and included two songs that were on their reunion album.[55] Around the same time, Barry and Robin were about to publish the book On the Other Hand.[18] They also recruited Geoff Bridgford as the group's official drummer. Bridgford had previously worked with the Groove and Tin Tin and played drums on Maurice's unreleased first solo album.[56]

In 1970, 2 Years On was released in October in the US and November in the UK. The lead single "Lonely Days" reached No. 3 in the United States, promoted by appearances on The Johnny Cash Show, J ohnny Carson's Tonight Show, The Andy Williams Show, The Dick Cavett Show and The Ed Sullivan Show.[18]

Their ninth album, Trafalgar, was released in late 1971. The single "How Can You Mend a Broken Heart" was their first to hit No. 1 on the US charts, while "Israel" reached No. 22 in the Netherlands. "How Can You Mend a Broken Heart" also brought the Bee Gees their first Grammy Award nomination for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals. Later that year, the group's songs were included in the soundtrack for the film Melody.[57]

In 1972, they hit No. 16 in the US with the non-album single "My World", backed by Maurice's composition "On Time". Another 1972 single, "Run to Me" from the LP To Whom It May Concern, returned them to the UK top 10 for the first time in three years.[40] Bridgford left the group partway through recording, and the band chose not to hire a new member to replace him.[58] The resulting three-piece lineup of Barry, Robin and Maurice would remain unbroken for the remainder of the band's active years. On 24 November 1972, the band headlined the "Woodstock of the West" Festival at the Los Angeles Coliseum (which was a West Coast answer to Woodstock in New York), which also featured Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder and the Eagles.[59][60] Also in 1972, the group sang "Hey Jude" with Wilson Pickett.[61]

By 1973, however, the Bee Gees were in a rut. The album Life in a Tin Can, released on Robert Stigwood's newly formed RSO Records, and its lead-off single, "Saw a New Morning", sold poorly with the single peaking at No. 94. This was followed by an unreleased album (known as A Kick in the Head Is Worth Eight in the Pants). A second compilation album, Best of Bee Gees, Volume 2, was released in 1973, although it did not repeat the success of Volume 1. On 6 April 1973 episode of The Midnight Special they performed "Money (That's What I Want)" with Jerry Lee Lewis.[62] Also in 1973, they were invited by Chuck Berry to perform two songs with him onstage at The Midnight Special: "Johnny B. Goode"[63] and "Reelin' and Rockin'".[64]

After a tour of the United States in early 1974 and a Canadian tour later in the year,[65] the group ended up playing small clubs.[66] As Barry joked, "We ended up in, have you ever heard of Batley's the variety club in (West Yorkshire) England?".[67]

On the advice of Ahmet Ertegun, head of their US label Atlantic Records, Stigwood arranged for the group to record with soul music producer Arif Mardin. The resulting LP, Mr. Natural, included fewer ballads and foreshadowed the R&B direction of the rest of their career. When it, too, failed to attract much interest, Mardin encouraged them to work within the soul music style. The brothers attempted to assemble a live stage band that could replicate their studio sound. Lead guitarist Alan Kendall had come on board in 1971 but did not have much to do until Mr. Natural. For that album, they added drummer Dennis Bryon, and they later added ex-Strawbs keyboard player Blue Weaver, completing the Bee Gees band that lasted through the late 1970s. Maurice, who had previously performed on piano, guitar, harpsichord, electric piano, organ, mellotron and bass guitar, as well as mandolin and Moog synthesiser, by then confined himself to bass onstage.[68]

1975–1979: Turning to disco

[edit]Main Course and Children of the World

[edit]

At Eric Clapton's suggestion, the brothers moved to Miami, Florida, early in 1975 to record at Criteria Studios. After starting off with ballads, they eventually heeded the urging of Mardin and Stigwood, and crafted more dance-oriented disco songs, including their second US No. 1, "Jive Talkin'", along with US No. 7 "Nights on Broadway". The band liked the resulting new sound. This time the public agreed by sending the LP Main Course up the charts. This album included the first Bee Gees songs wherein Barry used falsetto,[69] something that became a trademark of the band. This was also the first Bee Gees album to have two US top-10 singles since 1968's Idea.[citation needed] Main Course also became their first charting R&B album.[citation needed]

On the Bee Gees' appearance on The Midnight Special in 1975, to promote Main Course, they sang "To Love Somebody" with Helen Reddy.[70] Around the same time, the Bee Gees recorded three Beatles covers—"Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight", "She Came in Through the Bathroom Window" with Barry providing lead vocals, and "Sun King" with Maurice providing lead vocals, for the unsuccessful musical/documentary All This and World War II.[71]

The next album, Children of the World, released in September 1976, was filled with Barry's new-found falsetto and Weaver's synthesizer disco licks.[citation needed] The first single from the album was "You Should Be Dancing", which features percussion work by musician Stephen Stills.[72] The song pushed the Bee Gees to a level of stardom they had not previously achieved in the US, though their new R&B/disco sound was not as popular with some diehard fans. The pop ballad "Love So Right" reached No. 3 in the US, and "Boogie Child" reached US No. 12 in January 1977.[73] The album peaked at No. 8 in the US.[74]

Saturday Night Fever and Spirits Having Flown

[edit]Following a successful live album, Here at Last... Bee Gees... Live, the Bee Gees agreed with Stigwood to participate in the creation of the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. It was a turning point in their career. The cultural impact of both the film and the soundtrack was significant throughout the world, and epitomized the disco phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic.[75]

The band's involvement in the film did not begin until post-production. As John Travolta asserted, "The Bee Gees weren't even involved in the movie in the beginning ... I was dancing to Stevie Wonder and Boz Scaggs."[76] Producer Robert Stigwood commissioned the Bee Gees to create the songs for the film.[77] The brothers wrote the songs "virtually in a single weekend" at Château d'Hérouville studio in France.[76] Barry Gibb remembered the reaction when Stigwood and music supervisor Bill Oakes arrived and listened to the demos:

They flipped out and said these will be great. We still had no concept of the movie, except some kind of rough script that they'd brought with them. ... You've got to remember, we were fairly dead in the water at that point, 1975, somewhere in that zone—the Bee Gees' sound was basically tired. We needed something new. We hadn't had a hit record in about three years. So we felt, Oh Jeez, that's it. That's our life span, like most groups in the late '60s. So, we had to find something. We didn't know what was going to happen.[76]

Bill Oakes, who supervised the soundtrack, asserts that Saturday Night Fever did not begin the disco craze but rather prolonged it: "Disco had run its course. These days, Fever is credited with kicking off the whole disco thing—it really didn't. Truth is, it breathed new life into a genre that was actually dying."[76]

Three Bee Gees singles—"How Deep Is Your Love" (US No. 1, UK No. 3), "Stayin' Alive" (US No. 1, UK No. 4) and "Night Fever" (US No. 1, UK No. 1)—charted high in many countries around the world, launching the most popular period of the disco era.[40] They also penned the song "If I Can't Have You", which became a US No. 1 hit for Yvonne Elliman, while the Bee Gees' own version was the B-side of "Stayin' Alive". Such was the popularity of Saturday Night Fever that two different versions of the song "More Than a Woman" received airplay, one by the Bee Gees, which was relegated to an album track, and another by Tavares, which was the hit.[78]

During a nine-month period beginning in the Christmas season of 1977, seven songs written by the brothers held the No. 1 position on the US charts for 27 of 37 consecutive weeks: three of their own releases, two for brother Andy Gibb, the Yvonne Elliman single, and "Grease", performed by Frankie Valli.[79]

Fuelled by the film's success, the soundtrack broke multiple industry records, becoming the highest-selling album in recording history to that point. With more than 40 million copies sold, Saturday Night Fever is among music's top five best selling soundtrack albums. As of 2010[update], it is calculated as the fourth highest-selling album worldwide.[80]

In March 1978, the Bee Gees held the top two positions on the US charts with "Night Fever" and "Stayin' Alive", the first time this had happened since the Beatles. On the US Billboard Hot 100 chart for 25 March 1978, five songs written by the Gibbs were in the US top 10 at the same time: "Night Fever", "Stayin' Alive", "If I Can't Have You", "Emotion" and "Love Is Thicker Than Water". Such chart dominance had not been seen since April 1964, when the Beatles had all five of the top five American singles. Barry Gibb became the only songwriter to have four consecutive number-one hits in the US, breaking the John Lennon and Paul McCartney 1964 record. These songs were "Stayin' Alive", "Love Is Thicker Than Water", "Night Fever" and "If I Can't Have You".[81]

The Bee Gees won five Grammy Awards for Saturday Night Fever over two years: Album of the Year, Producer of the Year (with Albhy Galuten and Karl Richardson), two awards for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals (one in 1978 for "How Deep Is Your Love" and one in 1979 for "Stayin' Alive"), and Best Vocal Arrangement for Two or More Voices for "Stayin' Alive".[82]

During this era, Barry and Robin also wrote "Emotion" for an old friend, Australian vocalist Samantha Sang, who made it a top 10 hit, with the Bee Gees singing backing vocals. Barry also wrote the title song to the film version of the Broadway musical Grease for Frankie Valli to perform, which went to No. 1.[83]

The Bee Gees also co-starred with Peter Frampton in Robert Stigwood's film Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978), loosely inspired by the classic 1967 album by the Beatles. The movie had been heavily promoted prior to release and was expected to enjoy great commercial success. However, it was savaged by film critics as a disjointed mess and ignored by the public. The soundtrack charted top five in the U.S., but only top 38 in Britain. The single "Oh! Darling", credited to Robin Gibb, reached No. 15 in the US.[84]

The Bee Gees' follow-up to Saturday Night Fever was the Spirits Having Flown album. It yielded three more hits: "Too Much Heaven" (US No. 1, UK No. 3), "Tragedy" (US No. 1, UK No. 1), and "Love You Inside Out" (US No. 1, UK No. 13).[40] This gave the act six consecutive No. 1 singles in the US within a year and a half, equalling the Beatles and surpassed only by Whitney Houston.[85]

In January 1979, the Bee Gees performed "Too Much Heaven" as their contribution to the Music for UNICEF Concert at the United Nations General Assembly.[86] During the summer of 1979, the Bee Gees embarked on their largest concert tour covering the US and Canada. The Spirits Having Flown tour capitalised on Bee Gees fever that was sweeping the nation, with sold-out concerts in 38 cities. The Bee Gees produced a video for the title track "Too Much Heaven", directed by Miami-based filmmaker Martin Pitts and produced by Charles Allen. With this video, Pitts and Allen began a long association with the brothers.[87]

The Bee Gees even had a country hit in 1979 with "Rest Your Love on Me", the flip side of their pop hit "Too Much Heaven", which made the top 40 on the country charts. It was also a 1981 hit for Conway Twitty, topping the country music charts.[88]

The Bee Gees' success rose and fell with the disco bubble. By the end of 1979, disco was rapidly declining in popularity, and the backlash against disco put the Bee Gees' American career in a tailspin. Encouraged by Steve Dahl's Disco Demolition Night, radio stations around the US began promoting "Bee Gee-Free Weekends". Following their remarkable run from 1975 to 1979, the act had only one more top 10 single in the US, and that did not come until the single "One" reached number 7 in 1989.[14]

Barry Gibb considered the success of the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack both a blessing and a curse:

Fever was No. 1 every week ... It wasn't just like a hit album. It was No. 1 every single week for 25 weeks. It was just an amazing, crazy, extraordinary time. I remember not being able to answer the phone, and I remember people climbing over my walls. I was quite grateful when it stopped. It was too unreal. In the long run, your life is better if it's not like that on a constant basis. Nice though it was.[76]

1980–1986: Outside projects, band turmoil, solo efforts and decline

[edit]Robin co-produced Jimmy Ruffin's Sunrise released in May 1980, but the songs were started in 1979; the album contains songs written by the Gibb brothers, including the single "Hold On To My Love".[89]

In March 1980, Barry Gibb worked with Barbra Streisand on her album Guilty. He co-produced, and wrote or co-wrote all nine of the album's tracks (four of them written with Robin, and the title track with both Robin and Maurice). Barry also appeared on the album's cover with Streisand and duetted with her on two tracks. The album reached No. 1 in both the US and the UK, as did the single "Woman in Love" (written by Barry and Robin), becoming Streisand's most successful single and album to date. Both of the Streisand/Gibb duets, "Guilty" and "What Kind of Fool", also reached the US Top 10.[90]

In 1981, the Bee Gees released the album Living Eyes, their last full-length album release on RSO. This album was the first CD ever played in public, when it was played to viewers of the BBC show Tomorrow's World.[91] With the disco backlash still running strong, the album failed to make the UK or US Top 40—breaking their streak of Top 40 hits, which started in 1975 with "Jive Talkin'". Two singles from the album fared little better—"He's a Liar", which reached No. 30 in the US, and "Living Eyes", which reached No. 45.[citation needed]

In 1982, Dionne Warwick enjoyed a UK No. 2 and US Adult Contemporary No. 1 hit with her comeback single, "Heartbreaker", taken from her album of the same name, written largely by the Bee Gees and co-produced by Barry Gibb. The album reached No. 3 in the UK and the Top 30 in the US, where it was certified Gold.

A year later, Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers recorded the Bee Gees-penned track "Islands in the Stream", which became a US and Australian No. 1 hit and entered the Top 10 in the UK. Rogers' 1983 album, Eyes That See in the Dark, was written entirely by the Bee Gees and co-produced by Barry. The album was a Top 10 hit in the US and was certified Double Platinum.[92]

The Bee Gees had greater success with the soundtrack to Staying Alive in 1983, the sequel to Saturday Night Fever. The soundtrack was certified platinum in the US, and included their Top 30 hit "The Woman in You".[citation needed]

Also in 1983, the band was sued by Chicago songwriter Ronald Selle, who claimed the brothers stole melodic material from one of his songs, "Let It End", and used it in "How Deep Is Your Love". At first, the Bee Gees lost the case; one juror said that a factor in the jury's decision was the Gibbs' failure to introduce expert testimony rebutting the plaintiff's expert testimony that it was "impossible" for the two songs to have been written independently. However, the verdict was overturned a few months later.[93]

In August 1983, Barry signed a solo deal with MCA Records and spent much of late 1983 and 1984 writing songs for this first solo effort, Now Voyager.[94] Robin released three solo albums in the 1980s, How Old Are You?, Secret Agent and Walls Have Eyes. Maurice released his second single to date, "Hold Her in Your Hand", the first one having been released in 1970.[95]

In 1985, Diana Ross released the album Eaten Alive, written by the Bee Gees, with the title track co-written with Michael Jackson (who also performed on the track). The album was again co-produced by Barry Gibb, and the single "Chain Reaction" gave Ross a UK and Australian No. 1 hit.[96]

1987–1999: Comeback, return to popularity and Andy's death

[edit]The Bee Gees released the album E.S.P. in 1987, which sold over 2 million copies.[97] It was their first album in six years, and their first for Warner Bros. Records. The single "You Win Again" went to No. 1 in numerous countries, including the UK,[98] and made the Bee Gees the first group to score a UK No. 1 hit in each of three decades: the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.[99] The single was a disappointment in the US, charting at No. 75, and the Bee Gees voiced their frustration over American radio stations not playing their new European hit single, an omission which the group felt led to poor sales of their current album in the US. The song won the Bee Gees the 1987 British Academy's Ivor Novello Award for Best Song Musically and Lyrically, and in February 1988 the band received a Brit Award nomination for Best British Group.[100]

The Bee Gees later got together with Eric Clapton to create a group called 'the Bunburys' to raise money for English charities. The group recorded three songs for The Bunbury Tails: "We're the Bunburys" (which eventually became the opening theme to the 1992 animated series The Bunbury Tails), "Bunbury Afternoon", and "Fight (No Matter How Long)". The last song reached No. 8 on the rock music chart and appeared on The 1988 Summer Olympics Album.[101]

The Bee Gees' next album, One (1989), featured "Wish You Were Here", a song dedicated to their younger brother Andy, who had died in 1988 of myocarditis resulting from a viral infection. The album also contained their first US Top 10 hit (No. 7) in a decade, "One" (an Adult Contemporary No. 1). After the album's release, the band embarked on its first world tour in 10 years.[102]

In the UK, Polydor issued a single-disc hits collection from Tales called The Very Best of the Bee Gees, which contained their biggest UK hits. The album became one of their best-selling albums in that country, and was eventually certified Triple Platinum.[103]

Following their next album, High Civilization (1991), which contained the UK top five hit "Secret Love", the Bee Gees went on a European tour. After the tour, Barry Gibb began to battle a serious back problem, which required surgery. In addition, he had arthritis which, at one point, was so severe that it was doubtful that he would be able to play guitar for much longer. Also, in the early 1990s, Maurice Gibb finally sought treatment for his alcoholism, which he had battled for many years with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous.[104]

In 1993, the group returned to the Polydor label and released the album Size Isn't Everything, which contained the UK top five hit "For Whom the Bell Tolls". Success still eluded them in the US, however, as the first single released, "Paying the Price of Love", only managed to reach No. 74 on the Billboard Hot 100, while the parent album stalled at No. 153.[citation needed]

In 1997, they released the album Still Waters, which has reached No. 2 in the UK (their highest album chart position there since 1979) and No. 11 in the US. The album's first single, "Alone", gave them another UK Top 5 hit and a top 30 hit in the US. Still Waters was the band's most successful US release of their post-RSO era.[105]

At the 1997 BRIT Awards held in Earls Court, London on 24 February, the Bee Gees received the award for Outstanding Contribution to Music.[106] On 14 November 1997, the Bee Gees performed a live concert in Las Vegas called One Night Only. The show included a performance of "Our Love (Don't Throw It All Away)" synchronised with a vocal by their deceased brother Andy and a guest appearance by Celine Dion singing "Immortality". The "One Night Only" name grew out of the band's declaration that, due to Barry's health issues, the Las Vegas show was to be the final live performance of their career. After the immensely positive audience response to the Vegas concert, Barry decided to continue despite the pain, and the concert expanded into their last full-blown world tour of "One Night Only" concerts.[38][page needed] The tour included playing to 56,000 people at London's Wembley Stadium on 5 September 1998 and concluded in the newly built Olympic Stadium in Sydney, Australia on 27 March 1999 to 72,000 people.[38][page needed] During the One Night Only tour, the Bee Gees also finally gave live performances of Grease;[107] though Barry previously wrote the song for the 1978 film of the same name, it was performed mainly by Frankie Valli.[107]

In 1998, the group's soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever was incorporated into a stage production produced first in the West End and then on Broadway. They wrote three new songs for the adaptation. Also in 1998, the brothers released "Ellan Vannin" for Manx charities, recorded the previous year. Known as the unofficial national anthem of the Isle of Man, the brothers performed the song during their world tour to reflect their pride in the place of their birth.[108]

The Bee Gees closed the century with what turned out to be their last full-sized concert, known as BG2K, on 31 December 1999.[109]

2000–2008: This Is Where I Came In, Maurice's death, and split

[edit]In 2001, the group released what turned out to be their final album of new material, This Is Where I Came In. The album was another success, reaching the Top 10 in the UK (being certified Gold), and the Top 20 in the US. The title track was also a UK Top 20 hit single.[110] They celebrated their 35th anniversary, and the album, by performing on the television series Live by Request on the American cable television network A&E.[111]

The last concert of the Bee Gees as a trio was at the Love and Hope Ball in 2002.[112] Maurice Gibb died unexpectedly on 12 January 2003, at age 53, from a heart attack while awaiting emergency surgery to repair a strangulated intestine.[113] Initially, his surviving brothers announced that they intended to carry on the name "Bee Gees" in his memory, but as time passed they decided to retire the group's name, leaving it to represent the three brothers together.[114]

The same week that Maurice died, Robin's solo album Magnet was released. On 23 February 2003, the Bee Gees received the Grammy Legend Award, they also became the first recipients of that award in the 21st century. Barry and Robin accepted as well as Maurice's son, Adam, in a tearful ceremony.[115] On 2 May 2004, Barry and Robin Gibb received the CBE award at Buckingham Palace; their nephew Adam accepted his father Maurice's posthumous award.[116]

In late 2004, Robin embarked on a solo tour of Germany, Russia, and Asia. During January 2005, Barry, Robin, and several legendary rock artists recorded "Grief Never Grows Old", the official tsunami relief record for the Disasters Emergency Committee. Later that year, Barry reunited with Barbra Streisand for her top-selling album Guilty Pleasures, released as Guilty Too in the UK as a sequel album to the previous Guilty.[117] Also in 2004, Barry recorded his song "I Cannot Give You My Love" with Cliff Richard, which became a UK top 20 hit single; Maurice's keyboard work from a 2001 demo version was included in this 2003 version.[118][119]

In February 2006, Barry and Robin reunited on stage for a Miami charity concert to benefit the Diabetes Research Institute. It was their first public performance together since Maurice's death. The pair also played at the 30th annual Prince's Trust Concert in the UK on 20 May 2006.[120]

2009–2012: Return to performing and Robin's death

[edit]On 14 March 2009, Barry teamed with Olivia Newton-John to present the one-hour finale performance at a star-studded 12-hour live concert at Sydney's Sydney Cricket Ground, part of Sound Relief, a fundraiser to aid victims of the February 2009 Victorian Bushfires that devastated large tracts of heavily wooded and populated south-eastern Australia, where the Gibb family once lived. The concert was televised live nationally across Australia on the Max TV cable network.[121] On 10 July 2009, Barry and Robin were named as Freemen of the Borough of Douglas (Isle of Man); the award was also bestowed posthumously to Maurice.[122]

In late 2009, Barry and Robin announced plans to record and perform together once again as the Bee Gees.[123] Barry and Robin performed on the BBC's Strictly Come Dancing on 31 October 2009[124] and appeared on ABC-TV's Dancing with the Stars on 17 November 2009.[125] On 15 March 2010, Barry and Robin inducted the Swedish group ABBA into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[126] On 26 May 2010, the two made a surprise appearance on the ninth-season finale of American Idol.

On 20 November 2011, it was announced that Robin Gibb, at 61 years old, had been diagnosed with liver cancer, a condition he had become aware of several months earlier. He had become noticeably thinner in previous months and had to cancel several appearances due to severe abdominal pain.[127] Robin joined British military trio the Soldiers for the Coming Home charity concert on 13 February 2012 at the London Palladium, in support of injured servicemen. It was his first public appearance for almost five months and, as it turned out, his final one.[128] On 14 April 2012, it was reported that Robin had contracted pneumonia[129] in a Chelsea hospital and was in a coma.[130] Although he came out of his coma on 20 April 2012, his condition deteriorated rapidly[131] and he died on 20 May 2012 of liver and kidney failure.[132]

2013–present: Looking back at a lifetime of music

[edit]In September and October 2013, Barry performed his first solo tour "in honour of his brothers and a lifetime of music".[133] In addition to the Rhino collection, The Studio Albums: 1967–1968, Warner Bros. released a box set in 2014 called The Warner Bros Years: 1987–1991 that included the studio albums E.S.P., One and High Civilization as well as extended mixes and B-sides. It also included the band's entire 1989 concert in Melbourne, Australia, available only on video as All for One prior to this release.[134] The documentary The Joy of the Bee Gees was aired on BBC Four on 19 December 2014.[135]

On 23 March 2015, 13STAR Records released a box set 1974–1979 which included the studio albums Mr. Natural, Main Course, Children of the World and Spirits Having Flown. A fifth disc called The Miami Years includes all the tracks from Saturday Night Fever as well as B-sides. No unreleased tracks from the era were included.[136]

After a hiatus from performing, Barry Gibb returned to solo and guest singing performances. He occasionally appears with his son, Steve Gibb.[137] In 2016, he released In the Now, his first solo effort since 1984's Now Voyager. It was the first release of new Bee Gees-related music since the posthumous release of Robin Gibb's 50 St. Catherine's Drive. Also in 2016, Capitol Records signed a new distribution deal with Barry and the estates of his brothers for the Bee Gees catalogue, bringing their music back to Universal.[138][139]

In late 2020, a documentary titled The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart was released on HBO Max; it was received with positive reviews and won an Emmy award.[140][141] A few months later, an as-yet-untitled biopic about the Bee Gees was announced to be in development at Paramount, with Kenneth Branagh directing and Barry Gibb serving as an executive producer.[142][143]

Barry Gibb released his third solo studio album, Greenfields, on 8 January 2021. It consisted of re-imagined Bee Gees songs from throughout their career, newly recorded in a primarily acoustic style with vocal contributions from a variety of country musicians including Dolly Parton, Keith Urban and Miranda Lambert.[144] The album debuted at No. 1 in both the UK and Australia – the latter of which set a record for the oldest artist to top the ARIA charts – while also peaking at No. 15 on the US Billboard 200 (and No. 2 on the US Billboard Top Album Sales chart) and being met with favourable reviews.[145][146][147][148]

Influences

[edit]The Bee Gees were influenced by the Beatles, the Everly Brothers, the Mills Brothers, Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones,[149][150] Roy Orbison,[151] the Beach Boys[152] and Stevie Wonder.[153] On the 2014 documentary The Joy of the Bee Gees, Barry said that the Bee Gees were also influenced by the Hollies and Otis Redding.[154][155] Maurice noted that Neil Sedaka was an early influence,[156] and later the group was "very influenced" by Linda Creed songs for the Stylistics.[157]

Legacy

[edit]In his 1980 Playboy magazine interview, John Lennon praised the Bee Gees, "Try to tell the kids in the seventies who were screaming to the Bee Gees that their music was just the Beatles redone. There is nothing wrong with the Bee Gees. They do a damn good job. There was nothing else going on then."[158]

In a 2007 interview with Duane Hitchings, who co-wrote Rod Stewart's 1978 disco song "Da Ya Think I'm Sexy?", he noted that the song was[159]

a spoof on guys from the 'cocaine lounge lizards' of the Saturday Night Fever days. We Rock and Roll guys thought we were dead meat when that movie and the Bee Gees came out. The Bee Gees were brilliant musicians and really nice people. No big egos. Rod, in his brilliance, decided to do a spoof on disco. VERY smart man. There is no such thing as a "dumb" super success in the music business.[159]

Kevin Parker of Tame Impala has said that listening to the Bee Gees after taking mushrooms inspired him to change the sound of the music he was making on his album Currents.[160]

The English indie rock band the Cribs was also influenced by the Bee Gees. Cribs member Ryan Jarman said: "It must have had quite a big influence on us – pop melodies is something we always revert to. I always want to get back to pop melodies and I'm sure that's due to that Bee Gees phase we went through."[161]

Following Robin's death on 20 May 2012, Beyoncé remarked: "The Bee Gees were an early inspiration for me, Kelly Rowland and Michelle. We loved their songwriting and beautiful harmonies. Recording their classic song, 'Emotion' was a special time for Destiny's Child. Sadly we lost Robin Gibb this week. My heart goes out to his brother Barry and the rest of his family."[162]

Singer Jordin Sparks remarked that her favourite Bee Gees songs are "Too Much Heaven", "Emotion" (although performed by Samantha Sang with Barry on the background vocals using his falsetto), and "Stayin' Alive".[163]

Carrie Underwood said, about discovering the Bee Gees during her childhood, "My parents listened to the Bee Gees quite a bit when I was little, so I was definitely exposed to them at an early age. They just had a sound that was all their own, obviously, never duplicated."[163]

Songwriting

[edit]Everyone should be aware that the Bee Gees are second only to Lennon and McCartney as the most successful songwriting unit in British popular music.

—Music historian Paul Gambaccini.[164]

At one point, in 1978, the Gibb brothers were responsible for writing and/or performing nine of the songs in the Billboard Hot 100.[165] In all, the Gibbs placed 13 singles onto the Hot 100 in 1978, with 12 making the Top 40. The Gibb brothers are fellows of the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors (BASCA).[166] At least 2,500 artists have recorded their songs.[167]

Singer-songwriter Gavin DeGraw spoke about the Bee Gees' influence with their own music as well as their songwriting:

Let's talk about the Bee Gees. That's an iconic group. Not just a great band, but a great group of songwriters. Even long after the Bee Gees' success on the pop charts, they were still writing songs for other people, huge hit songs. Their talent went far beyond their moment of normal pop success. It is a loss to the music industry and a loss of an iconic group. The beauty of this industry is that we do pay tribute and every artist coming up is a fan of a generation prior to it, so there's a real tradition element to it".[163]

In 2009, as part of the Q150 celebrations, the Bee Gees were announced as one of the Q150 Icons of Queensland for their role as "Influential Artists".[168]

Accolades and achievements

[edit]

In 1978, following the success of Saturday Night Fever, and the single "Night Fever" in particular, Reubin Askew, the governor of the US state of Florida, named the Bee Gees honorary citizens of the state, since they resided in Miami at the time.[169] In 1979, the Bee Gees got their star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. They were the subjects of This Is Your Life in 1991 when they were surprised by Michael Aspel while being interviewed by disc jockey Steve Wright (DJ) on his Radio 1 programme at BBC Broadcasting House.[170]

The Bee Gees were inducted in 1994 into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, as well as Florida's Artists Hall of Fame in 1995 and the ARIA Hall of Fame in 1997. Also in 1997, the group were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; the presenter of the award to "Britain's First Family of Harmony" was Brian Wilson, historical leader of the Beach Boys, another "family act" featuring three harmonising brothers.[171] In 2001, they were inducted into the Vocal Group Hall of Fame.[172] After Maurice's death, the Bee Gees were also inducted into the Dance Music Hall of Fame in 2001, They were made Ivor Novello fellows and inducted into London's Walk of Fame in 2006 and the Musically Speaking Hall Of Fame in 2008. On 15 May 2007, the Bee Gees were named BMI Icons at the 55th annual BMI Pop Awards. Collectively, Barry, Maurice and Robin Gibb have earned 109 BMI Pop, Country and Latin Awards.[173]

In October 1999, the Isle of Man Post Office unveiled a set of six stamps honouring the Bee Gees.[174]

In the 2002 New Year's Honours, announced on 31 December 2001, all three brothers were appointed as Commanders of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). By the time of the investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace on 27 May 2004 Maurice had died, and he was represented at the ceremony by his son Adam.[175][176] On 10 July 2009, the Isle of Man's capital bestowed the Freedom of the Borough of Douglas honour on Barry and Robin, as well as posthumously on Maurice.[177] On 20 November 2009, the Douglas Borough Council released a limited edition commemorative DVD to mark their naming as Freemen of the Borough.[178]

On 14 February 2013, Barry Gibb unveiled a statue of the Bee Gees as well as unveiling "Bee Gees Way" (a walkway filled with photos and videos of the Bee Gees) in honour of the Bee Gees in Redcliffe, Queensland, Australia.[179][180][181][182] On 27 June 2018, Barry Gibb, the last surviving member of the Bee Gees, was knighted by Prince Charles after being named on the Queen's New Year's Honours List.[183][184] The statue of the Bee Gees in Douglas, Isle of Man, was installed in 2021.

In 2022, Barry Gibb was made an Honorary Companion of the Order of Australia which is Australia's highest national honour.[185]

In 2023, Barry Gibb became a Kennedy Center Honoree for contributions to American culture and for being a "pop music pioneer",[186]as well as being inducted along with his brothers into the Australian Songwriters Association Hall of Fame.[citation needed][clarification needed]

The Bee Gees have sold over 250 million records worldwide,[187][188] making them one of the best-selling artists of all time. The group are to date the most successful family and sibling band of all time, the most successful musical trio of all time, and the most successful musical act with ties to Australia.[189][190][citation needed]

Awards and nominations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

Queensland Music Awards

[edit]The Queensland Music Awards (previously known as Q Song Awards) are annual awards celebrating Queensland's brightest emerging artists and established legends. They commenced in 2006.[198]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result (wins only) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009[199] | Bee Gees | Grant McLennan Lifetime Achievement Award | awarded |

Members

[edit]|

Principal members

Touring musicians

|

Guest musicians (studio and touring)

|

Timeline

[edit]

Timeline of touring members

[edit]

Discography

[edit]Soundtracks Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Staying Alive (1983) are not official Bee Gees albums, but contain some previously unreleased tracks. Apart from live and compilation, all their official albums are included on this list. A Kick in the Head Is Worth Eight in the Pants has not been included on the list because it appeared only on numerous bootlegs and was not officially released.[citation needed]

Studio albums

[edit]- The Bee Gees Sing and Play 14 Barry Gibb Songs (1965)

- Spicks and Specks (1966)

- Bee Gees' 1st (1967)

- Horizontal (1968)

- Idea (1968)

- Odessa (1969)

- Cucumber Castle (1970)

- 2 Years On (1970)

- Trafalgar (1971)

- To Whom It May Concern (1972)

- Life in a Tin Can (1973)

- Mr. Natural (1974)

- Main Course (1975)

- Children of the World (1976)

- Spirits Having Flown (1979)

- Living Eyes (1981)

- E.S.P. (1987)

- One (1989)

- High Civilization (1991)

- Size Isn't Everything (1993)

- Still Waters (1997)

- This Is Where I Came In (2001)

Concert tours

[edit]- The Bee Gees' concerts in 1967 and 1968 (1967–1968)

- 2 Years On Tour (1971)

- Trafalgar Tour (1972)

- Mr. Natural Tour (1974)

- Main Course Tour (1975)

- Children of the World Tour (1976)

- Spirits Having Flown Tour (1979)

- One for All World Tour (1989)

- High Civilization World Tour (1991)

- One Night Only World Tour (1997–1999)

- This Is Where I Came In (2001)

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Cucumber Castle | Hugh Gladwish |

| 1978 | Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band | Michael Schultz |

| 1997 | Keppel Road | Tony Cash |

| 2010 | In Our Own Time | Martyn Atkins |

| 2020 | The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart | Frank Marshall |

| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Idea | Jean-Christophe Averty |

| 1979 | The Bee Gees Special | Louis J. Horvitz |

| 1994 | Space Ghost Coast to Coast | C. Martin Croker, Jeff Doud |

| 2001 | This Is Where I Came In | David Leaf, John Scheinfield |

| 2001 | Live By Request | Lawrence Jordan |

| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 | One for All Tour | Adrian Woods, Peter Demetris |

| 1997 | One Night Only | Bee Gees |

References

[edit]- ^ "Soft Rock Music Artists". AllMusic. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Bee Gees – Biography & History". AllMusic.

- ^ "Colin Peterson – Biography & History". AllMusic.

- ^ Meagher, John (16 January 2021). "Ten songs that tell the story of the Bee Gees". The Independent.

- ^ "The Career of Disco Kings the Bee Gees is Explored in New Documentary". janksreviews.com. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "The Bee Gees | Rhino". www.rhino.com.

- ^ "Boogie to the sounds of the disco days during the 'Best of the Bee Gees Weekend'". 19 January 2021.

- ^ Maidment, Adam (20 January 2020). "Chorlton building where the Bee Gees first performed faces demolition after bid to save it rejected". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Rolland, David (7 October 2020). "You Might Feel Like Dancing After Seeing The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart". Miami New Times. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Bee Gees | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "The Bee Gees Make the Pop of Ages – idobi Network". idobi.com. 19 November 2001.

- ^ "The Bee Gees biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. 1997. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Inductees: Bee Gees". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. 1997. Archived from the original on 16 June 2005. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ a b Caulfield, Keith (21 May 2012). "Bee Gees Rank Third Among Groups for Most Hot 100 No. 1s in History". Billboard. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (8 September 2009). "Bee Gees to re-form for live comeback". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "Robin Gibb, Bee Gees Co-Founder, Dead at 62". Rolling Stone. 20 May 2012.

- ^ Adriaensen, Marion. "The story about The Bee Gees/Part 2—1950–1960". Brothers Gibb. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Andrew (2009). The Bee Gees – Tales of the Brothers Gibb. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857120045. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Dolgins, Adam (1998), Rock Names: From Abba to ZZ Top (3rd ed.), Citadel, p. 24

- ^ "Behind the Name: Bee Gees – Bee Gees". beegees.com. 21 August 2017. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "The Bee Gees Redcliffe – The Gibbs Brothers Timeline". Visitmoretonbayregion.com.au. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Adriaensen, Marion. "History Part 3 – The Story of the Bee Gees: 1960–1965". Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Mitchell, Alex (30 May 2004). "Bob Carr's tribute to Bee Gees". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Robin Gibb Sings Song For Sydney On Final Album". noise11.com. 3 August 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Seiler, Melissa (27 September 2016). "'Tragedy' after the Bee Gees' former Maroubra home demolished". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "MILESAGO – Record Labels – Spin Records". www.milesago.com. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "DOWNUNDER RECORDS". milesago.com. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Bee Gees' Former Label Boss Nat Kipner Dies". Billboard. 9 December 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Those old hits keep Stayin' Alive". www.dailytelegraph.com.au. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Graff, Gary (20 May 2012). "Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees Dead at 62". Billboard. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Moser, Margaret; Crawford, Bill (April 2007). Rock Stars Do The Dumbest Things. St. Martin's Publishing. ISBN 9781429978385. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Show 49 – The British are Coming! The British are Coming!: With an emphasis on Donovan, The Bee Gees, and The Who, Part 6". Digital Library. UNT. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "The Bee Gees release their first international hit New York Mining Disaster 1941 in 1967". Pop Expresso. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "To Love Somebody – The Songs Of The Bee Gees 1966–1970 – Record Collector Magazine". Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Bee Gees". Billboard. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Bee Gees, The* – BBC Sessions 1967–1973". Discogs. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (20 July 1967). "The Children of Rock; Belt the Blues". Billboard. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bilyeu, Cook & Hughes 2009.

- ^ "Rhino Factoids: Bee Gees Christmas Special – Rhino". Rhino.com. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bee Gees: UK Charts History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 4 December 2014

- ^ "Official Charts - Bee Gees". Official Charts. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Scott-Irvine, Henry (20 November 2012). Procol Harum: The Ghosts Of A Whiter Shade of Pale. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857128027. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "17 March 1968: The Bee Gees, Lucille Ball, George Hamilton, Fran Jeffries", The Ed Sullivan show, TV, archived from the original on 17 October 2013, retrieved 14 May 2013

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "1968". Gibb Songs. Columbia. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "Obituary: Robin Gibb". BBC News. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1969". Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (20 May 2012). "Robin Gibb, a Bee Gee With a Taciturn Manner, Dies at 62". New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Lesley Gibb Joins Brothers of the Bee Gees". Newspaper.com. Detroit Free Press. 4 July 1969. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Friday Nuggets: Early Bee Gees Drum Fun". Modern Drummer. 28 October 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (14 July 2019). "Australian Singers Turned Actors". Filmink.

- ^ Sandoval, Andrew (2012). The Day-By-Day Story, 1945–1972 (paperback) (1st ed.). Retrofuture Day-By-Day. pp. 102–115. ISBN 978-0-943249-08-7.

- ^ "Bee Gees Discography: Maurice Gibb – Railroad (Single)". Mcdustsucker.de. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Barry Gibb – I'll Kiss Your Memory / This Time". Discogs. May 1970. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Furness, Hannah (14 April 2015). "'Lost' Robin Gibb album to be released thanks to fans". Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "Gibb Songs : 1970". columbia.edu.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1969". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (19 January 2023). "The Bee Gees' 40 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Golson, Tyler (1 September 2021). "The 10 best Bee Gees songs of all time". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Sweatman, Stu. "1972 – The Los Angeles Coliseum plays host to the Woodstock of the West". This Day in Rock. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "November 24". 93.3 KDKB Rocks Arizona. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ POLLOIDER (26 February 2007). "Wilson Pickett and Bee Gees Hey Jude". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ JerryLeeLewisTV (13 February 2009). "Jerry Lee Lewis & Bee Gees -Money (Live 1973)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ julio on line (29 May 2011). "Bee Gees Chuck Berry Johnny B Goode (Live At Midnight Special 73).mpg". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Mark Pountney Music (10 June 2007). "Reelin' and Rockin' - Chuck Berry The Midnight Special 1973 with Bee Gees". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Melhuish, Martin (12 October 1974). "From the Music Capitals of the World". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. pp. 47–. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1974". Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Meyer, David N. (9 July 2013). The Bee Gees: The Biography. Hachette Books. ISBN 9780306821578. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Martin, Philip (10 January 2021). "CRITICAL MASS: A diminished chord — The story of the Bee Gees". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ James, Nicholas. "Main Course – Bee Gees". Bee Gees reviews. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "HELEN REDDY JAMMING WITH THE BEE GEES – MIDNIGHT SPECIAL – THE QUEEN OF 70s POP". YouTube. 30 January 2012. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1975". Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Stephen Stills interview: 'We're still here, haha haha ha!'". 17 August 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1977". Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1976". Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Sullivan, James (14 January 2003). "APPRECIATION / Contributor to a sound that went beyond disco". sfgate.com. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Sam Kashner, "Fever Pitch", Movies Rock (Supplement to The New Yorker), Fall 2007, unnumbered page.

- ^ Rose, Frank (14 July 1977). "How Can You Mend a Broken Group? The Bee Gees Did It With Disco". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "More Than A Woman - Which Version Is Best?". Smooth Radio. Global. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Gibb Songs: 1978". Columbia University. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Record-Breakers and Trivia—Albums". Every hit. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Brownfield, Troy (4 April 2019). "Beating the Beatles: Can Anyone Take the Top Five Again?". saturdayeveningpost.com. Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ McLellan, Joseph; Zibart, Eve (16 February 1979). "Billy Joel's Ballad Upsets Bees Gees' Anthem". Washington Post. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Golsen, Tyler (17 September 2023). "Why didn't Barry Gibb sing the 'Grease' theme song?". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Robin Gibb". Billboard. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Jet". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company: 54. 2 May 1988. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ^ Fred Bronson, "Too Much Heaven", in The Billboard Book of Number One Hits (Los Angeles: Billboard Books, 2003), 496. ISBN 0823076776, 9780823076772

- ^ On Pitts, see https://imvdb.com/n/martin-pitts

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book Of Top 40 Country Hits: 1944–2006, Second edition. Record Research. p. 360.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1980". Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "New Barbra Streisand-Barry Gibb Collaborative Album, 'Guilty Pleasures,' to be Released as CD and DualDisc on Tuesday, September 20". Sony Music Entertainment. 29 August 2005. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Bilyeu, Melinda; Cook, Hector; Hughes, Andrew Môn (2004). The Bee Gees: tales of the brothers Gibb. Omnibus Press. p. 519. ISBN 978-1-84449-057-8.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L.; Freeman, Jon (21 March 2020). "Kenny Rogers: 10 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1983". Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 1984". Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Hughes, Andrew (2009). The Bee Gees – Tales of the Brothers Gibb. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857120045. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Hayes, Jim (17 March 2021). "The top ten this week in 1986: dazzling Diana Ross leads star studded line-up". Irish Independent. Independent News & Media.

- ^ Fegiz, Mario Luzzato (25 April 1989). "Una lacrima nel ritorno dei Bee Gees". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). p. 25. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

L'album "ESP", che, con due milioni di copie vendute il mondo (cifra lontana dai record dei passato, battutu solo da

- ^ Roberts, David (2006), British Hit Singles & Albums, London: Guinness World Records

- ^ Rees, Dafydd; Crampton, Luke (1991), "Part 2", Rock movers & shakers, vol. 1991, p. 46

- ^ Lister, David (28 May 1994). "Pop ballads bite back in lyrical fashion: David Lister charts a sea change away from rap towards memorable melodies". The Independent. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "The Bee Gees Meet Eric Clapton". Uncle John's Bathroom Reader. 27 June 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (3 August 1989). "THE BEE GEES, AFTER THE FEVER". Washington Post. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Crone, Madeline (7 April 2021). "Barry Gibb Shares Stories Behind Bee Gees' Biggest Hits". American Songwriter. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Maurice Gibb's harmonizing influence". The Washington Times. 18 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Bee Gees :: Stayin' Alive". Музыкальная Газета (in Russian) (35). 1998. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Brit Awards, 1997, archived from the original on 12 November 2011, retrieved 9 December 2011

- ^ a b "Behind The Track: "Grease"". beegees.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "The Bee Gees – Born in the Isle of Man". 2iom. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "In pictures: Celebrity celebrations worldwide". BBC News. 1 January 2000. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Results Matching: This Is Where I Came In". Official Charts Company. 7 April 2001. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Jeckell, Barry A. (25 April 2001). "Billboard Bits: Bee Gees, Music Midtown, Ween, and More". Billboard. Billboard. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Média, Bell. "What Happened February 23rd In Pop Music History". www.iheartradio.ca. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Bee Gees question brother's treatment". BBC News. 13 January 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ "Bee Gees band name dropped". BBC News. 22 January 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ "The 45th Annual Grammy Awards" (Payment required to access full article). The Philadelphia Inquirer. 24 February 2003. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Barry, Robin and Maurice's son Adam received the CBE award". Brothersgibb.org. 27 May 2004. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "When Barry Gibb tenderly kissed Barbra Streisand live on stage at the 1981 Grammy Awards". Smooth Radio. Global Entertainment. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Joseph Brennan – Gibb Songs: 2003". Columbia.edu. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "Cliff Richard". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Bee Gees (Barry – Robin) Princes Trust Concert". YouTube. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "SOUND RELIEF :: SYDNEY INFO". Sound Relief. Archived from the original on 14 October 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Rachael Bruce (10 July 2009). "Bee Gees named Freemen of the Borough". Isle of Man Today. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- ^ BBC News (15 October 2009). "Bee Gees to perform on Strictly". Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ "Bee Gees to perform on Strictly". BBC News. 15 October 2009. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ "Stayin' Alive". The New York Times. 28 November 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ "The Stooges, ABBA Headline Eclectic Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Ceremony". MTV. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ Singh, Anita (20 November 2011). "Robin Gibb diagnosed with liver cancer". The Sunday Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ "Robin Gibb and The Soldiers in concert". Haig Housing Trust Coming Home. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Gibb fights for life with pneumonia". The Associated Press. 14 April 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Donnelly, Laura (14 April 2012). "Robin Gibb in coma and fighting for his life". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "Robin Gibb making good progress". NZ: TV. 21 April 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Robin Gibb of Bee Gees dies at 62". USA Today. 14 April 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Nicholas, Sadie (29 April 2013). "The last surviving Bee Gee speaks movingly of life without his lost siblings". Express.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph. "Gibb Songs: 2014". Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "The Joy of the Bee Gees". BBC Four. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Sinclair, Paul (2 February 2015). "Bee Gees/ 1974–1979 five-disc box". superdeluxeedition.com. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Howard (19 September 2015). "Musician-songwriter Stephen Gibb got a hard-rocking start". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Roshanian, Arya (29 November 2016). "Capitol Records Signs Bee Gees to Long-Term Contract, Aims to 'Reinvigorate' Catalog". Variety. Variety Media, LLC. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "Capitol Records signs the Bee Gees to long-term worldwide agreement encompassing the legendary group's entire catalogue of recorded music". Universal Music Group. 29 November 2016.

- ^ "The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart - Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart". Television Academy. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (10 March 2021). "Kenneth Branagh to Direct Bee Gees Biopic for Paramount". Variety.

- ^ Melas, Chloe (11 March 2021). "Kenneth Branagh to direct Bee Gees movie". CNN.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (8 January 2021). "Barry Gibb Returns With Country Collection 'Greenfields' Featuring Dolly Parton, Keith Urban & More: Listen". Billboard. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Barry Gibb lands his first solo Number 1 album with Greenfields". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Barry Gibb scores first solo ARIA Charts #1 album". www.aria.com.au. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (20 January 2021). "Barry Gibb Scores Top 5 Debut on Billboard's Top Album Sales Chart With 'Greenfields'". Billboard. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers Songbook, Vol. 1 by Barry Gibb, retrieved 15 May 2023

- ^ Bee Gees Influences and Legacy, Shmoop, archived from the original on 28 August 2013, retrieved 16 May 2013

- ^ "Bee Gees Music Influences". MTV. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Bee Gees | Similar Artists". AllMusic. 21 January 2003. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Endless Harmony: The Beach Boys Story (1998 documentary)

- ^ "Olivia Newton John – Andy Gibb & Bee Gees in The Australian Music Awards 1982". YouTube. 18 March 2009. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "The Joy of the Bee Gees BBC Full HD Documentary 2014". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "New Documentaries 2015 The Joy of the Bee Gees BBC Full HD Documentary". YouTube. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Gibb, Maurice; Gibb, Barry; Gibb, Robin (2 February 2002). "Interview With the Bee Gees". CNN Larry King Weekend (Interview). Interviewed by Larry King. Atlanta: Cable News Network. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ White, Timothy (24 March 2001). "The Billboard Interview". Billboard. pp. B-22. Retrieved 4 April 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "John Lennon Interview: Playboy 1980 (Page 3)". The Beatles Ultimate Experience. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ a b Urban "Wally" Wallstrom (23 March 2007), "Duane Hitchings, The Man Behind the Hits", RockUnited.com, retrieved 18 January 2013

- ^ "Tame Impala's Kevin Parker reveals listening to the Bee Gees while on drugs inspired his new album". NME. 4 July 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "The Cribs: 'Robin Gibb's music with the Bee Gees really influenced us' – video". NME. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Beyonce Tributes Bee Gees Singer Robin Gibb". Idolator. 23 May 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "Robin Gibb Mourned By Justin Bieber, Carrie Underwood". MTV News. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Bee Gees' singer Robin Gibb dies after cancer battle". BBC News. 20 May 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Cat's field". NZ. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ Fellows, The British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors (BASCA), archived from the original on 30 October 2013, retrieved 30 May 2012

- ^ "Visual, performing arts, music". AllBusiness. Retrieved 9 July 2011.