Harmonic seventh chord

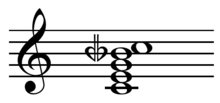

The harmonic seventh chord is a major triad plus the harmonic seventh interval (ratio of 7:4, about 968.826 cents[1]). This interval is somewhat narrower (about 48.77 cents flatter, a septimal quarter tone) and is "sweeter in quality" than an "ordinary"[2] minor seventh, which has a just intonation ratio of 9:5[3] (1017.596 cents), or an equal-temperament ratio of 1000 cents (25⁄6:1).

Uses

[edit]Since barbershop music tends to be sung in just intonation, the barbershop seventh chord may be accurately termed a harmonic seventh chord. As guitars, pianos, and other equal-temperament instruments cannot play this chord, it is frequently approximated by a dominant seventh chord. A frequently encountered example of the harmonic seventh chord is the last word of the "... and many more!" modern addition (which is formally referred to as a tag) to the song "Happy Birthday to You" When sung by professional singers, the harmony on the word "more" typically takes the form of a harmonic seventh chord.[4] The use of dominant seventh chords in blues may be an approximation of an older practice of using harmonic seventh chords.[5]

Wendy Carlos's alpha scale has, "excellent harmonic seventh chords ... using the inversion of 7:4, i.e. 8 / 7 " (a septimal whole tone).[6] ⓘ.

It is suggested that the harmonic seventh on the dominant not be used as a suspension, since this would create a mistuned fourth over the tonic.[7] The harmonic seventh of G, F![]() +, is lower than the perfect fourth over C, F♮, by Archytas' comma (27.25 cents). 22 equal temperament avoids this problem because it tempers out this comma, while still offering a reasonably good approximation of the harmonic seventh chord.

+, is lower than the perfect fourth over C, F♮, by Archytas' comma (27.25 cents). 22 equal temperament avoids this problem because it tempers out this comma, while still offering a reasonably good approximation of the harmonic seventh chord.

Barbershop seventh

[edit]

barbershop seventh chord. A chord consisting of the root, third, fifth, and flatted seventh degrees of the scale. It is characteristic of barbershop arrangements. When used to lead to a chord whose root is a fifth below the root of the barbershop seventh chord, it is called a dominant seventh chord. Barbershoppers sometimes refer to this as the 'meat 'n' taters chord'. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these chords were sometimes called 'minors'. [as in minor seventh chord]"

— Averill 2003[8]

The barbershop seventh is the name commonly given by practitioners of barbershop music to the seventh of and the major-minor seventh or dominant seventh chord, when it is used in a barbershop arrangement or performance. "Society arrangers believe that a song should contain anywhere from 35–60 percent dominant seventh chords to sound 'barbershop'—and when they do, barbershoppers speak of being in 'seventh heaven.'"[9]

Barbershop music features both major-minor seventh chords with dominant function (resolving down a perfect fifth), often in chains (secondary dominants), and nondominant major-minor seventh chords.[10]

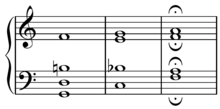

Beginning in the 1940s, barbershop revival singers "have self-consciously tuned their dominant seventh and tonic chord in just intonation to maximize the overlap of common tones, resulting in a ringing sound rich in harmonics" called 'extended sound', 'expanded sound', 'fortified sound', "the voice of the angels".[11] The first positive mention of such practice appears to be by Reagan (1944).[12] The example of a dominant chord tuned to 100, 125, 150, and 175 Hz, or the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th harmonics of a 25 Hz fundamental is given,[11] making the seventh of the chord a "harmonic seventh".

There's a chord in a barbershop that makes the nerve ends tingle ... . We might call our chord a Super-Seventh! ... The notes of our chord have the exact frequency ratios 4–5–6–7. With these ratios, overtones reinforce overtones. There's a minimum of dissonance and a distinctive ringing sound. How can you detect this chord? It's easy: You can't mistake it, for the signs are clear; the overtones will ring in your ears; you'll experience a spinal shiver; bumps will stand out on your arms; you'll rise a trifle in your seat.

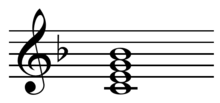

It is normally voiced with the lowest note (the bass) on a root or a fifth, and its close harmony sound is one of the hallmarks of barbershop music.

When tuned in just intonation (as in barbershop singing), this chord is called a harmonic seventh chord.

Comparison with equal temperament

[edit]

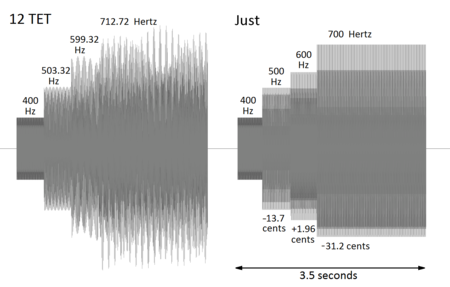

Audacity can be used to render pure tone versions of the harmonic seventh with both equal-tempered and just tuning. These signals can also be graphed in order to illustrate the more complex pattern associated with the equal tempered scale. Both chords are based on a pitch of 400 Hz, with the just pitches at 500, 600, and 700 Hz.

The figure also shows the discrepancy between the just scale in comparison to the equal-tempered scale (in cents). For example, the just tone at 500 Hz is flatter than 503.2 Hz by 13.69 cents. Also, the 600 Hz tone is sharp by 1.955 cents, and the 700 Hz tone is flat by 31.17 cents.

| Tuning | Dominant seventh | Harmonic seventh |

|---|---|---|

| Just intonation | ||

| 12-TET (72-TET) | ||

| 19-TET | ||

| 31-TET | ||

| 43-TET |

References

[edit]- ^ Bosanquet, Robert Holford Macdowall (1876). An elementary treatise on musical intervals and temperament, pp. 41-42. Diapason Press; Houten, The Netherlands. ISBN 90-70907-12-7.

- ^ "On Certain Novel Aspects of Harmony", p.119. Eustace J. Breakspeare. Proceedings of the Musical Association, 13th Sess., (1886–1887), pp. 113–131. Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Musical Association.

- ^ "The Heritage of Greece in Music", p.89. Wilfrid Perrett. Proceedings of the Musical Association, 58th Sess., (1931–1932), pp. 85–103. Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Musical Association.

- ^ Mathieu, W.A. (1997). Harmonic Experience. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International. p. 126. ISBN 0-89281-560-4.

- ^ The world's most important chord progression (video) – via YouTube.

- ^ Carlos, Wendy (1989–1996). "Three asymmetric divisions of the octave". WendyCarlos.com.

- ^ Halford, Robert; Bosanquet, MacDowall; Rasch, Rudolf (1876). An Elementary Treatise on Musical Intervals and Temperament. London, UK: MacMillan. p. 41–42.

- ^ Averill, Gage (2003). Four Parts, No Waiting: A social history of American barbershop harmony. p. 205. ISBN 0-19-511672-0.

- ^ Averill (2003), p. 163.

- ^ McNeil, W.K. (2005). Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music. p. 26. ISBN 9780415941792.

- ^ a b c Averill (2003), p. 164

- ^ Reagan, 'Molly' (1944). "Mechanics of barbershop harmony". Harmonizer.

- ^ Merrill, Art (1951). "You can call off the search — for we've found the lost chord". Harmonizer. Vol. 10, no. 3. p. 27. Cited in Averill (2003), p. 164.

External links

[edit]- Play that barbershop chord (YouTube video)