Baranof Island

Native name: Sheet’-ká X'áat'l | |

|---|---|

Islands of the Pacific Northwest Coast | |

| Geography | |

| Location | ABC islands of Alaska |

| Coordinates | 56°57′05″N 134°56′52″W / 56.95139°N 134.94778°W |

| Archipelago | Alexander Archipelago |

| Area | 1,607 sq mi (4,160 km2) |

| Length | 100 mi (200 km) |

| Width | 30 mi (50 km) |

| Highest elevation | 5,390 ft (1643 m) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | Alaska |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 8532 (2000) |

| Pop. density | 2.05/km2 (5.31/sq mi) |

Baranof Island[a] is an island in the northern Alexander Archipelago in the Alaska Panhandle, in Alaska. The name "Baranof" was given to the island in 1805 by Imperial Russian Navy captain U. F. Lisianski in honor of Alexander Andreyevich Baranov.[1] It was called Sheet’-ká X'áat'l (often expressed simply as "Shee"[2]) by the native Tlingit people. It is the smallest of the ABC islands of Alaska. The indigenous group native to the island, the Tlingit, named the island Shee Atika. Baranof island is home to a diverse ecosystem, which made it a prime location for the fur trading company, the Russian American Company. The Russian occupation of Baranof Island impacted not only the indigenous population and the ecology of the island, but also led to the United States' current ownership over the land.

Geography

[edit]The island has a land area of 1,607 square miles (4,162 square kilometres),[3] which is slightly larger than the state of Rhode Island. It measures 105 miles (169 km)[3] by 30 miles (48 km) at its longest point and perpendicular widest point, respectively. It has a shoreline of 617 miles (993 kilometres).[4] Baranof Island hosts Peak 5390, the highest mountain in the Alexander Archipelago, and is the eighth largest island by area in Alaska, the tenth largest island in the United States, and the 137th largest island in the world. Its center is near 57°0′N 135°0′W / 57.000°N 135.000°W. Most of the island lies within the limits of Tongass National Forest. A large part has been officially designated as the South Baranof Wilderness. A little bay called Ommaney Bay is located on the south end of the island. The escort carrier USS Ommaney Bay (CVE-79) bears its name.

Wildlife

[edit]Baranof Island is home to a diverse ecosystem, mainly containing land and ocean mammals.[5] The most notable species include brown bears, Sitka black tailed deer, sea otters, sea lions, dolphins, porpoises, mountain goats, and humpback whales. Steller, the prominent species of sea lions in the area, use the southern tip of Baranof Island as a breeding ground. This led to the area becoming a protected part of Alaska's Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, as one of five sea lion breeding areas in Southeast Alaska.[5]

A recent decline in the mountain goat population of Baranof Island has led researchers to monitor the population, in order to determine the best means of increasing population numbers. Originally, it was believed no mountain goats were native to the island, and mountain goats were actually imported into Baranof island from neighboring islands. Through research it was found that there may have been an indigenous species of mountain goat to Baranof Island, as the mountain goats prominent today can be traced back to two different lineages.[6]

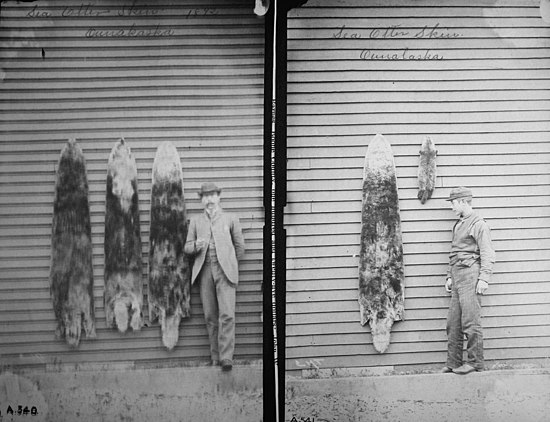

Sea otters and fur trading

[edit]Sea otters have had a fluctuating population on and near Baranof Island since the colonization of the island by Russian explorers, as the mammal's population became largely protected due to its likelihood of being hunted into extinction. At the start of colonization of Baranof Island and other Russian-Alaskan territories, sea otter pelts were demanded from indigenous tribes as tribute for the new Russian settlers.[7] Because sea otters solely rely on their fur for warmth rather than a layer of fat like many other aquatic mammals, their fur is particularly dense. The fur quickly became popular in China, and were often described as luxurious and extremely soft.[8] The demand for sea otter pelts was so strong that sea otter fur established the Russian-Alaskan economy, but also extremely diminished the sea otter population on and surrounding Baranof Island.

After the United States had purchased the territory known as Russian Alaska, Great Britain, Japan, Russia, and the United States all signed the International Fur Seal Treaty in 1911, pledging an end to the sale of sea otter fur.[8] Since then, other marine and environmental protection efforts have continued to prohibit the sale of sea otter fur including the 1972 United States Marine Mammal Protection Act, as well as the Endangered Species Act in 1977.[8] Each environmental protection against the sale and hunt of sea otters and their furs, allows for Alaskan indigenous hunting. Only specific groups of Alaskan native ethnic groups that currently dwell in Alaska are permitted to hunt and use sea otters for subsistence uses as well as for the creation of indigenous group articles.[8]

History

[edit]The first European settlement on the island was established in 1799 by Alexander Baranov, the chief manager and first governor of the Russian-American Company for whom the island and Archipelago are named. The island was the center of Russian activity in North America during the period from 1804 to 1867 and was the headquarters of the Russian fur-trading interest. The fur trading consisted of mainly sea otter pelts, fur seal pelts, and fox pelts, but it was mainly sea otter pelts that were obtained from Baranof Island.[9]

As with many of its previously colonized territories, the Russian government instated a tribute system wherein the heads of Indigenous groups were responsible for paying Russian tribute collectors. Because it is difficult to trap sea otters and Tlingit men, the men of the Indigenous group to Baranof Island, had become skilled at doing so, the Russians chose sea otter pelts as the item of tribute. This secured labor allowed the Russians to establish the Russian-American Company.[7] The Russian American Company was responsible for the governing of Baranof Island and all of Russian Alaska, including the indigenous group, the Tlingits.[10] The Company remained profitable until sea otter and other hunted mammals had their populations severely diminished, and the company could no longer rely on the sale of pelts for profit. During this time, Russia was forced to surrender its war efforts against France and Britain in the Crimean War, which led to significant financial strains for the Russian government.[11] Thus, the Russian Tsar sold the entire territory of Russian-Alaska to the United States government in 1867.[9] The United States government was eager to expand and create a rapport with Russia, so Alaska was purchased at an approximate cost of two cents per acre, or $7.2 million exactly.[11]

Around 1900, Baranof Island was subject to many small-scale mining ventures, especially centered on Sitka and on the north side of the island around Rodman Bay. Canneries, whaling stations, and fox farms were established on Baranof Island and smaller islands around it, though most had been abandoned by the beginning of World War II. The remains of these outposts are still evident, though most exist in a dilapidated condition.

In February 1924 the Alaska Territorial Game Commission hired Charlie Raatakainen to transplant mainland goats from near Juneau to Bear Mountain. Raatakainen hired a group of Finns aboard his boat the Pelican to complete the job, though one of the group died in the process.[12]

The 1939 Slattery Report on Alaskan development identified the island as one of the areas where new settlements would be established through immigration. This plan was never implemented.

Communities

[edit]The population of the island was 8,532 at the 2000 census.

Almost the entire area of the island is part of the City and Borough of Sitka (Sitka also extends northward onto Chichagof Island). The only part of Baranof that is not in Sitka is a tiny sliver of land (9.75 km2) at the extreme southeast corner, which is in the Petersburg Borough, and includes the town of Port Alexander. This section had a 2000 census population of 81 persons. The towns of Baranof Warm Springs, Port Armstrong, and Port Walter are also located on the eastern side of the island. Goddard, a now-abandoned settlement about 16 miles (26 kilometres) south of Sitka, features a few private homes and hot springs with two public bathhouses. There are also five year-round salmon hatcheries, one located just north of Port Alexander at Port Armstrong, another located just north of Baranof Warm Springs at Hidden Falls, two are located in the city of Sitka one at the Sitka Sound Science Center, and another in the Sawmill Cove Business Park; the other just south of Sitka near Medvejie Lake. The latter is accessible by private road from Sitka. All of these communities, except for Port Alexander and Port Armstrong, are under the jurisdiction of the City and Borough of Sitka, of which, Sitka serves as the borough seat.

The Indigenous group to Baranof Island is the Tlingit group. The island was originally named Shee Atika, meaning "outside the shee".[13] The Tlingit people fished, hunted, trapped, and traded goods with neighboring Indigenous groups. Items of trade mainly included furs such as sea otter and fur seal pelts, copper, and dried fish.[13] It was the Tlingit that the original Russian explorers first colonized, forcing the native men into labor by taking native women and children as hostages.[7] The Tlingit were seen as useful to the Russians, as Tlingit hunters could kill sea otters with ease, a task that proved particularly difficult for Russian fur trappers themselves because of the natural agility of the otters, as well as their aquatic habitat. The Tlingit were subjected to exploitative practices by the Russians, and in 1802, the group rebelled against Russian forces by attacking the Russian outpost, Redoubt Saint Michael, just northwest of Baranof Island.[13]

The native's success did not last long after this rebellion, and the Russians with Aluet allies took back the fort and the land that the Tlingits then occupied in a six-day-long effort. The Russians were victorious, as the Tlingit had fled their land, and were not to return until 1821. By this time, the Russian-American Company was in need of the Tlingit hunting abilities, and invited the native group back to their original land on Baranof Island with the agreement of no more raids into Russian territory.[13] Hostility between the Russians and the Tlingit continued as late as 1855.[14] Tlingit culture is still prevalent on Baranof Island today, and their culture is kept alive through the continuation of several indigenous practices, such as making otter pelt goods.[5]

Fishing, seafood processing, and tourism are important industries on the island, which is also famous for brown bears and Sitka deer.

Fictional accounts

[edit]Louis L'Amour's novel Sitka describes the conflict between the Russian fur trading empire and yankee settlers.

The island features prominently in James A. Michener's multigenerational novel Alaska.

The Yiddish Policemen's Union is a 2007 alternate-history novel by Michael Chabon about a Jewish Yiddish-speaking territory in Sitka, including most of Baranof Island.[15] The novel proceeds from the counter-factual premise that the Slattery Report had actually been implemented.

Local author John Straley has written a number of mystery novels set on and around Baranof Island.

The Sea Runners, a 1982 novel by Ivan Doig.

Sitka is a setting in the 2009 film The Proposal, although the scenes were filmed in Rockport, Massachusetts.

See also

[edit]- List of mountain peaks of North America

- List of Ultras of the United States

- List of geographic features on Baranof Island

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Orth, Donald J. (1967). Dictionary of Alaska Place Names, Geological Survey, Professional Paper 567. Washington: United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ Orth, Donald J. (1967). Dictionary of Alaska Place Names, Geological Survey, Professional Paper 567. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. Spelled "Shi" in Orth's citation of Hodge.

- ^ a b DeArmond, R. N. (1995). Southeast Alaska: Names on the Chart and how they get there. Juneau, Alaska: Ripley/DeArmond.

- ^ DeArmond, R. N.; Patricia Roppel (1997). Baranof Island's Eastern Shore: "The Waterfall Coast". Sitka, Alaska: Arrowhead Press. p. 7.

- ^ a b c State of Alaska, Department of Fish and Game (2022-10-23). "Virtual Wildlife Viewing - Podcasts, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". www.adfg.alaska.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ White, Kevin; Mooney, Phil (2022-10-23). "Mountain Goat Research in Alaska, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". www.adfg.alaska.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ a b c Miller, Gwen A (2007). Stoler, Ann (ed.). Haunted by empire geographies of intimacy in North American history. Duke University Press. pp. 303–304. ISBN 978-0-8223-3724-9. OCLC 934508140.

- ^ a b c d Tran, Lynn (2003) [2003-07-12]. "Alaskan sea otter mystery - History". cmast.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ a b National Park Service, Department of Interior (2022-10-24). "The Russians - Sitka National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Gibson, James R. (2022-10-27). "Why the Russians Sold Alaska". login.access.library.miami.edu. Wilson Quarterly. pp. 183–186. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ a b Owens, Kenneth; Petrov, Alexander Yu (2016). "Empire Maker: Aleksandr Baranov and Russian Colonial Expansion into Alaska and Northern California". login.access.library.miami.edu. pp. 164–177. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- ^ Yaw, W. Leslie (2001). Targets Hit and Targets Missed: hunting in Southeast Alaska. Ward Cove, Alaska: Ocean's Edge Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 0-9712475-0-1.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service, Department of Interior (2022-10-24). "The Tlingit - Sitka National Historical Park". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Gibson, James (1998). Pacific Historical Review Vol. 67, No. 1. University of California Press. p. 71.

- ^ "Novel involving Alaska Jewish colony is rooted in history Archived August 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine," Tom Kizzia, Anchorage Daily News.

External links

[edit]- Tlingit Geographical Place Names for the Sheet’Ka Kwaan — Sitka Tribe of Alaska, an interactive map of Sitka Area native place names.