Bald's Leechbook

Bald's Leechbook (also known as Medicinale Anglicum) is an Old English medical text probably compiled in the ninth-century, possibly under the influence of Alfred the Great's educational reforms.[1]

It takes its name from a Latin verse colophon at the end of the second book which begins Bald habet hunc librum Cild quem conscribere iussit, meaning "Bald owns this book which he ordered Cild to compile."[1]

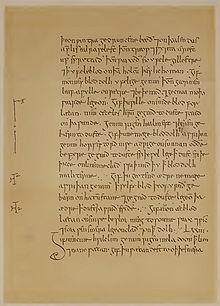

The text survives in only one manuscript, held in London at the British Library.[2] The manuscript contains one further medical text, called Leechbook III, which is also included in this entry.

Structure and content

Both books are organised in a head-to-foot order, but the first book deals with external maladies, the second with internal disorders. Cameron notes that "This separation of external and internal diseases may be unique in medieval medical texts".[3]

Cameron notes that "in Bald's Leechbook is the only plastic surgery mentioned in Anglo-Saxon records".[4] The recipe in particular prescribes surgery for a Cleft lip and palate, Leechbook i, chapter 13 (pr Cockayne p 56).

Cameron also notes that of the Old English Medical compilations "Leechbook iii reflects most closely the medical practice of the Anglo-Saxons while they were still relatively free of Mediterranean influences," in contrast to Bald's Leechbook which "shows a conscious effort to transfer to Anglo-Saxon practice what one physician considered most useful in native and Mediterranean medicine," and the Lacnunga, which is "a sort of common place book with no other apparent aim than to record whatever items of medical interest came to the scribe's attention".[5]

Rev. Oswald Cockayne, editor and translator of an 1865 edition of the Leechbook, made note in his introduction of what he termed 'a Norse element' in the text, and gave, as example, words such torbegate, rudniolin, ons worm and Fornets palm.[6]

Cures

One cure for headache was to bind a stalk of crosswort to the head with a red kerchief. Chilblains were treated with a mix of eggs, wine, and fennel root. Agrimony was cited as a cure for male impotence - when boiled in milk, it could excite a man who was "insufficiently virile;" when boiled in Welsh beer it would have the opposite effect. The remedy for shingles comprised a potion using the bark of 15 trees: aspen, apple, maple, elder, willow, sallow, myrtle, wych-elm, oak, blackthorn, birch, olive, dogwood, ash, and quickbeam.[7]

A remedy for aching feet called for leaves of Elder, Waybroad and Mugwort to be pounded together, applied to the feet, then the feet bound.[8] In another, after offering a ritualistic cure for a horse in pain requiring the words Bless all the works of the lord of lords to be inscribed on the handle of a dagger, the author adds that the pain may have been caused by an elf.[9]

In March 2015, the Leechbook made the news when one of its recipes – which included garlic and the bile from a cow's stomach – was tested in the United Kingdom as a potential agent for use against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[10]

Contents of the MS

- ff. 1-6v Table of Contents to Leechbook i; pr. Cockayne vol. 2, pp. 2–16

- ff. 6v-58v Leechbook i; pr. Cockayne vol. 2, pp. 18–156

- ff. 58v-65 Table of Contents to Leechbook ii; pr Cockayne vol. 2, pp. 158–174

- ff. 65-109 Leechbook ii; 68 recipes. pr Cockayne 176-298. Cockayne provides missing chapter between 56 and 64 from London, BL, Harley 55. Chapter 64 is glossed as having been sent along with exotic medicines from Patriarch Elias of Jerusalem to Alfred the Great, which is the basis for the book's association with the Alfredian court.

- f. 109 A metrical Latin Colophon naming Bald as the owner of the book, and Cild as the compiler.

- ff. 109-127v "Leechbook iii." A collection of 73 medicinal recipes not associated with Bald due to its location after the metrical colophon.

- ff. 127v-end De urinis ?

Editions and facsimiles

Cockayne, T. O. Leechdoms Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England Being a Collection of Documents, for the Most Part Never Before Printed Illustrating the History of Science in this Country Before the Norman Conquest, 3 vols., London: Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores (Rolls Series) 35 i–iii, 1864–6 (reprint 1965) vol. 2.

Leonhardi, Günther. Kleinere angelsächsische Denkmäler I, Bibliothek der angelsächsischen Prosa 6, Kassel, 1905.

Wright, C. E., ed. Bald’s Leechbook: British Museum Royal manuscript 12 D.xvii, with appendix by R. Quirk. Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile 5, Copenhagen : Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1955

Digital facsimile at the British Library

See also

- Meaney, A. L. 'Variant Versions of Old English Medical Remedies and the Compilation of Bald's Leechbook, Anglo-Saxon England 13 (1984) pp. 235–68.

- Payne, J. F. English Medicine in Anglo-Saxon Times, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904.

- Pettit, E. Anglo-Saxon Remedies, Charms, and Prayers from British Library MS Harley 585: The ‘Lacnunga’, 2 vols., Lewiston and Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001. [Edition, with translation and commentary, of an Anglo-Saxon medical compendium that includes many variant versions of remedies also found in Bald's Leechbook.]

References

- ^ a b Nokes, Richard Scott ‘The several compilers of Bald’s Leechbook’ in Anglo-Saxon England 33 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 51-76

- ^ Ker, N. R. Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon, Oxford: 1957, Reprint with addenda 1990. Item 264.

- ^ Cameron, M. L., Anglo-Saxon Medicine, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 7, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, p 42.

- ^ Cameron, M. L., Anglo-Saxon Medicine, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 7, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 169.

- ^ Cameron, M. L., Anglo-Saxon Medicine, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 7, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 35.

- ^ Thomas Oswald Cockayne (15 November 2012). Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England: Being a Collection of Documents Illustrating the History of Science in this Country Before the Norman Conquest. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-108-04308-3.

- ^ Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger:The Year 1000: What Life Was Like at the Turn of the First Millennium Little, Brown, 2000 ISBN 0-316-51157-9

- ^ Thomas Oswald Cockayne (1865). Leechdoms, wortcunning, and starcraft of early England: being a collection of documents, for the most part never before printed, illustrating the history of science in this country before the Norman conquest. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green. p. 69.

- ^ John McKinnell; Daniel Anlezark (2011). Myths, Legends, and Heroes: Essays on Old Norse and Old English Literature in Honour of John McKinnell. University of Toronto Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8020-9947-1.

- ^ Clare Wilson. "Anglo Saxon remedy kills hospital superbug MRSA". New Scientist. Retrieved 31 March 2015.