Black Lives Matter

Logo and flag often used in the Black Lives Matter movement | |

| Date | 2013–present |

|---|---|

| Location | International, largely in the United States |

| Also known as |

|

| Cause | Racial discrimination and police brutality against black people |

| Motive | Anti-racism |

| Outcome |

|

Black Lives Matter (BLM) is a decentralized political and social movement[1][2] that aims to highlight racism, discrimination, and racial inequality experienced by black people and to promote anti-racism. Its primary concerns are police brutality and racially motivated violence against black people.[3][4][5][6][7] The movement began in response to the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Rekia Boyd, among others. BLM and its related organizations typically advocate for various policy changes related to black liberation[8] and criminal justice reform. While there are specific organizations that label themselves "Black Lives Matter", such as the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation, the overall movement is a decentralized network with no formal hierarchy.[9] As of 2021[update], there are about 40 chapters in the United States and Canada.[1] The slogan "Black Lives Matter" itself has not been trademarked by any group.[10]

In 2013, activists and friends Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi originated the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on social media following the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of African-American teen Trayvon Martin. Black Lives Matter became nationally recognized for street demonstrations following the 2014 deaths of two more African Americans, Michael Brown—resulting in protests and unrest in Ferguson, Missouri—and Eric Garner in New York City.[11][12] Since the Ferguson protests, participants in the movement have demonstrated against the deaths of numerous other African Americans by police actions or while in police custody. In the summer of 2015, Black Lives Matter activists became involved in the 2016 United States presidential election.[13]

The movement gained international attention during global protests in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.[14][15] An estimated 15 to 26 million people participated in Black Lives Matter protests in the United States, making it one of the largest protest movements in the country's history.[16] Despite being characterized by opponents as violent, the overwhelming majority of BLM demonstrations have been peaceful.[17]

The popularity of Black Lives Matter has shifted over time, largely due to changing perceptions among white Americans. In 2020, 67% of adults in the United States expressed support for the movement, declining to 51% of U.S. adults in 2023.[18][19][20][21] Support among people of color has, however, held strong, with 81% of African Americans, 61% of Hispanics and 63% of Asian Americans expressing support for Black Lives Matter as of 2023.[18]

Structure and organization

Decentralization

The phrase "Black Lives Matter" can refer to a Twitter hashtag, a slogan, a social movement, a political action committee,[22] or a loose confederation of groups advocating for racial justice. As a movement, Black Lives Matter is grassroots and decentralized, and leaders have emphasized the importance of local organizing over national leadership.[23][24] The structure differs from previous black movements, like the Civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Such differences have been the subject of scholarly literature.[25] Activist DeRay McKesson has commented that the movement "encompasses all who publicly declare that black lives matter and devote their time and energy accordingly."[26]

In 2013, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi formed the Black Lives Matter Network. Garza described the network as an online platform that existed to provide activists with a shared set of principles and goals. Local Black Lives Matter chapters are asked to commit to the organization's list of guiding principles but are autonomous,[1]: 124 operating without a central structure or hierarchy. Garza has commented that the Network was not interested in "policing who is and who is not part of the movement."[27][28] As of 2021[update], there are about 40 chapters in the United States and Canada.[1]: 124

The loose structure of Black Lives Matter has contributed to confusion in the press and among activists, as actions or statements from chapters or individuals are sometimes attributed to "Black Lives Matter" as a whole.[29][30] Matt Pearce, writing for the Los Angeles Times, commented that "the words could be serving as a political rallying cry or referring to the activist organization. Or it could be the fuzzily applied label used to describe a wide range of protests and conversations focused on racial inequality."[31]

On at least one occasion, a person represented as Managing Director of BLM Global Network has released a statement represented to be on behalf of that organization.[32]

Broader movement

Concurrently, a broader movement involving several other organizations and activists emerged under the banner of "Black Lives Matter", as well.[33][34] In 2015, Johnetta Elzie, DeRay Mckesson, Brittany Packnett, and Samuel Sinyangwe initiated Campaign Zero, aimed at promoting policy reforms to end police brutality. The campaign released a ten-point plan for reforms to policing, with recommendations including: ending broken windows theory policing, increasing community oversight of police departments, and creating stricter guidelines for the use of force.[35] The New York Times reporter, John Eligon, wrote that some activists expressed concerns that the campaign was overly focused on legislative remedies for police violence.[36]

Black Lives Matter also voices support for various movements and causes beyond police brutality, including LGBTQ activism, feminism, immigration reform, and economic justice.[37]

Movement for Black Lives

The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) is a coalition of more than 50 groups representing the interests of black communities across the United States.[38] Members include the Black Lives Matter Network, the National Conference of Black Lawyers, and the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights.[39] Endorsed by groups such as Color of Change, Race Forward, Brooklyn Movement Center, PolicyLink, Million Women March Cleveland, and ONE DC,[40] the coalition receives communications and tactical support from an organization named Blackbird.[41]

Following the murder of George Floyd, M4BL released the BREATHE Act, which called for sweeping legislative changes surrounding policing; the policy bill included calls to divest from policing and reinvest funds directly in community resources and alternative emergency response models.[42][43]

On July 24, 2015, the movement initially convened at Cleveland State University where between 1,500 and 2,000 activists gathered to participate in open discussions and demonstrations. The conference in Cleveland, Ohio initially attempted to "strategize ways for the Movement for Black Lives to hold law enforcement accountable for their actions on a national level".[44][45][46] However, the conference resulted in the formation of a much more significant social movement. At the end of the three-day conference, on July 26, the Movement for Black Lives initiated a yearlong "process of convening local and national groups to create a United Front".[44] This year long process ultimately resulted in the establishment of an organizational platform that articulates the goals, demands, and policies which the Movement for Black Lives supports in order to achieve the "liberation" of black communities across America.[44]

In 2016, the Ford Foundation announced plans to fund the M4BL Movement for Black Lives in a "six-year investments" plan, further partnering up with others to found the Black-led Movement Fund.[47][48][49] The sum donated by the Ford Foundation and the other donors to M4BL was reported as $100 million by The Washington Times in 2016 (equivalent to $127 million in 2023[50]); another donation of $33 million (equivalent to $42 million[50]) to M4BL was reportedly issued by the Open Society Foundations.[51][52]

In 2016, M4BL called for decarceration in the United States, reparations for harms related to slavery, and more recently, specific remedies for redlining in housing, education policy, mass incarceration and food insecurity.[53] It also called for an end to mass surveillance, investment in public education, not incarceration, and community control of the police: empowering residents in communities of color to hire and fire police officers and issue subpoenas, decide disciplinary consequences and exercise control over city funding of police.[54][55]

Funding

Politico reported in 2015 that the Democracy Alliance, a gathering of Democratic-Party donors, planned to meet with leaders of several groups who were endorsing the Black Lives Matter movement.[56] According to Politico, Solidaire, the donor coalition focusing on "movement building" and led by Texas oil fortune heir Leah Hunt-Hendrix, a member of the Democracy Alliance, had donated more than $200,000 to the BLM movement by 2015.[56]

According to The Economist, between May 2020 and December 2020, donations to Black Lives Matter related causes amounted to $10.6 billion (equivalent to $12 billion in 2023[50]).[57] The Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation, one of the main organizations coordinating organizing and mobilization efforts across the reported raising $90 million in 2020 (equivalent to $106 million in 2023[50]), including a substantial number of individual donations online, with an average donation of $30.76 (equivalent to $36.21[50]).[58][59]

Strategies and tactics

Black Lives Matter originally used various social media platforms—including hashtag activism—to reach thousands of people rapidly.[60] Since then, Black Lives Matter has embraced a diversity of tactics.[61] Black Lives Matter protests have been overwhelmingly peaceful; when violence does occur, it is often committed by counter-protesters.[62][63][64] Despite this, opponents often try to portray the movement as violent.[64][65]

Internet and social media

In 2014, the American Dialect Society chose #BlackLivesMatter as their word of the year.[66][67] Yes! Magazine picked #BlackLivesMatter as one of the twelve hashtags that changed the world in 2014.[68] From July 2013 through May 1, 2018, the hashtag "#BlackLivesMatter" had been tweeted over 30 million times, an average of 17,002 times per day.[69] By June 10, 2020, it had been tweeted roughly 47.8 million times,[70] with the period of July 7–17, 2016 having the highest usage, at nearly 500,000 tweets a day.[69] This period also saw an increase in tweets using the hashtags "#BlueLivesMatter" and "#AllLivesMatter".[69] On May 28, 2020, there were nearly 8.8 million tweets with the hashtag, and the average had increased to 3.7 million a day.[70]

The 2016 shooting of Dallas police officers saw the online tone of the movement become more negative than before, with 39% of tweets using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter expressing opposition to the movement.[71] Nearly half in opposition tied the group to violence, with many describing the group as terrorist.[71]

Khadijah White, a professor at Rutgers University, argues that BLM has ushered in a new era of black university student movements. The ease with which bystanders can record graphic videos of police violence and post them onto social media has driven activism all over the world.[72] The hashtag's usage has gained the attention of high-ranking politicians and has sometimes encouraged them to support the movement.[25]

On Wikipedia, a WikiProject dedicated to coverage of the Black Lives Matter movement was created in June 2020.[73]

In 2020, users of the popular app TikTok noticed that the app seemed to be shadow banning posts about BLM or recent police killings of black people.[failed verification] TikTok apologized and attributed the situation to a technical glitch.[74]

Direct action

BLM generally engages in direct action tactics that make people uncomfortable enough that they must address the issue.[75][76] BLM has been known to build power through protest and rallies.[77] BLM has also staged die-ins and held one during the 2015 Twin Cities Marathon.[78]

Political slogans used during demonstrations include the eponymous "Black Lives Matter", "Hands up, don't shoot" (a later discredited reference attributed to Michael Brown[79]), "I can't breathe"[80][81] (referring to Eric Garner and later George Floyd), "White silence is violence",[82] "No justice, no peace",[83][84] and "Is my son next?",[85] among others.

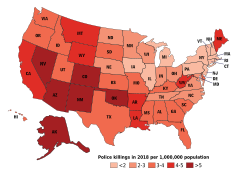

According to a 2018 study, "Black Lives Matter protests are more likely to occur in localities where more black people have previously been killed by police."[86]

Media, music and other cultural impacts

Since the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter,[87] the movement has been depicted and documented in film, song, television, literature, and the visual arts. A number of media outlets are providing material related to racial injustice and the Black Lives Matter movement. Published books, novels, and TV shows have increased in popularity in 2020.[88] Songs, such as Michael Jackson's "They Don't Care About Us" and Kendrick Lamar's "Alright", have been widely used as a rallying call at demonstrations.[89][90]

The short documentary film, Bars4Justice, features brief appearances by various activists and recording artists affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement. The film is an official selection of the 24th Annual Pan African Film Festival. Stay Woke: The Black Lives Matter Movement is a 2016 American television documentary film, starring Jesse Williams, about the Black Lives Matter movement.[91][92]

The February 2015 issue of Essence magazine and the cover was devoted to Black Lives Matter.[93] In December 2015, BLM was a contender for the Time magazine Person of the Year award, coming in fourth of the eight candidates.[94]

A number of cities have painted murals of "Black Lives Matter" in large letters on their streets. The cities include Washington, D.C., Dallas, Denver, Charlotte, Seattle, Brooklyn, Los Angeles, and Birmingham, Alabama.[95][96]

On May 9, 2016, Delrish Moss was sworn in as the first African American police chief in Ferguson, Missouri. He acknowledged that he faces such challenges as diversifying the police force, improving community relations, and addressing issues that catalyzed the Black Lives Matter movement.[97]

Allegations of use of excessive force by police

According to a study from the Bureau of Justice Statistics from 2002 to 2011, among those who had contact with the police, "blacks (2.8%) were more likely than whites (1.0%) and Hispanics (1.4%) to perceive the threat or use of nonfatal force was excessive."[98]

According to The Washington Post, police officers shot and killed 1,001 people in the United States in 2019. About half of those killed were white, and one quarter were black, making the rate of deaths for black Americans (31 fatal shootings per million) more than twice as high as the rate for white Americans (13 fatal shootings per million).[99][100] The Washington Post also counts 13 unarmed black Americans shot dead by police in 2019.[101]

A 2015 study by Cody Ross, UC Davis found "significant bias in the killing of unarmed black Americans relative to unarmed white Americans" by police. The study found that unarmed African Americans had 3.49 times the probability of being shot compared to unarmed whites, although in some jurisdictions the risk could be as much as 20 times higher. The study found that 2.79 more armed blacks were shot than unarmed blacks. The study also found that the documented county-level racial bias in police shootings could not be explained by differences in local crime rates.[102]

A 2019 study by Cesario et al. published in Social Psychological and Personality Science found that after adjusting for crime, there was "no systematic evidence of anti-black disparities in fatal shootings, fatal shootings of unarmed citizens, or fatal shootings involving misidentification of harmless objects".[103] However, a 2020 study by Cody Ross et al. criticizes the data analysis used in the Cesario et al. study. Using the same data set for police shootings in 2015 and 2016, Ross et al. conclude that there is significant racial bias in police shooting cases involving unarmed black suspects. This bias is not seen when suspects were armed.[104]

A study by Harvard economist Roland Fryer found that blacks and Hispanics were 50% more likely to experience non-lethal force in police interactions, but for officer-involved shootings there were "no racial differences in either the raw data or when contextual factors are taken into account".[105]

A 2019 study in PNAS concluded that black people were actually less likely than white people to be killed by police, based on the death rates in police encounters.[106] The authors later retracted the paper because although "our data and statistical approach were appropriate for investigating whether officer characteristics are related to the race of civilians fatally shot by police," the paper had been "cited as providing support for the idea that there are no racial biases in fatal shootings, or policing in general" whereas in fact their analyses "are inadequate to address racial disparities in the probability of being shot."[107]

Another study found that such conclusions were erroneous due to Simpson's paradox.[108][109] According to the paper, while it was true that white people were more likely to be killed in a police encounter, overall black people were still being discriminated against because they were more likely to have interactions with the police due to structural racism.[108] They are more likely to be stopped for more petty crimes or for no crime at all. Conversely, white people interact with police more rarely, and often for more serious crimes such as shootings, where police are more likely to use force. The same paper also backed up the findings of Ross and Fryer, and concluded that overall rate of death was a much more useful statistic than the rate of death in encounters.[108]

Disproportionate policing of Black Lives Matter events

Black Lives Matter protesters are themselves sometimes subject to excessive policing of the kind against which they are demonstrating. In May 2020, in addition to police, 43,350 military troops were deployed against Black Lives Matter protesters nationally.[110] Military surveillance aircraft were deployed against subsequent Black Lives Matter protests.[110] Observers, such as U.S. President Joe Biden, have noted that violent far-right mobilizations, including the 2021 United States Capitol attack, attracted smaller and more passive police presences than peaceful Black Lives Matter protests.[111][112][113][114][115] In November 2015, a police officer in Oregon was removed from street duty following a social media post in which he said he would have to "babysit these fools", in reference to a planned BLM event.[116]

According to a report released by the Movement for Black Lives in August 2021, the United States federal government deliberately targeted Black Lives Matter protesters in an attempt to disrupt and discourage the Black Lives Matter movement during the summer of 2020. According to the report, "The empirical data and findings in this report largely corroborate what Black organizers have long known intellectually, intuitively, and from lived experience about the federal government's disparate policing and prosecution of racial justice protests and related activity".[117]

Timeline of notable events and demonstrations in the United States

2014

In 2014, Black Lives Matter demonstrated against the deaths of numerous African Americans by police actions, including those of Dontre Hamilton, Eric Garner, John Crawford III, Michael Brown, Ezell Ford, Laquan McDonald, Akai Gurley, Tamir Rice, Antonio Martin, and Jerame Reid, among others.[118]

In July, Eric Garner died in New York City, after a New York City Police Department officer put him in a banned chokehold while arresting him. Garner's death has been cited as one of several police killings of African Americans that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement.[119]

During the Labor Day weekend in August, Black Lives Matter organized a "Freedom Ride", that brought more than 500 African-Americans from across the United States into Ferguson, Missouri, to support the work being done on the ground by local organizations.[120][121] The movement continued to be involved in the Ferguson protests, following the killing of Michael Brown.[122] The protests at times came into conflict with local and state police departments, who typically responded in an armed manner. At one point the National Guard was called in and a state of emergency was declared.[24]

Also in August, Los Angeles Police Department officers shot and killed Ezell Ford; BLM protested his death in Los Angeles into 2015.[123]

In November, a New York City Police Department officer shot and killed, Akai Gurley, a 28-year-old African-American man. Gurley's death was later protested by Black Lives Matter in New York City.[124] In Oakland, California, fourteen Black Lives Matter activists were arrested after they stopped a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) train for more than an hour on Black Friday, one of the biggest shopping days of the year. The protest, led by Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza, was organized in response to the grand jury decision not to indict Darren Wilson for the killing of Michael Brown.[125][126]

Also in November, Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old African-American boy was shot and killed by a Cleveland police officer. Rice's death has also been cited as contributing to "sparking" the Black Lives Matter movement.[119][127]

In December, two to three thousand people gathered at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota, to protest the killings of unarmed black men by police.[128] The police at the mall were equipped with riot gear and bomb-sniffing dogs; at least twenty members of the protest were arrested.[129][130] Management said that they were "extremely disappointed that organizers of Black Lives Matter protest chose to ignore our stated policy and repeated reminders that political protests and demonstrations are not allowed on Mall of America property".[129]

In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, BLM protested the police killing of Dontre Hamilton, who died in April.[131] Black Lives Matter protested the killing of John Crawford III.[132] The Murder of Renisha McBride was protested by Black Lives Matter.[133]

Also in December, in response to the decision by the grand jury not to indict Darren Wilson on any charges related to the killing of Michael Brown, a protest march was held in Berkeley, California. Later, in 2015, protesters and journalists who participated in that rally filed a lawsuit alleging "unconstitutional police attacks" on attendees.[134]

A week after the Michael Brown verdict, two police officers were killed in New York City by Ismaaiyl Brinsley, who expressed a desire to kill police officers in retribution for the deaths of Garner and Brown. Black Lives Matter condemned the shooting, though some right-wing media attempted to connect the group to it, with the Patrolman's Benevolent Association president claiming that there was "blood on [the] hands [of] those that incited violence on the street under the guise of protests".[24] A conservative television commentator also attempted to connect Black Lives Matter to protesters chanting that they wanted to see "dead cops," at the December "Millions March" which was organized by different groups.[24]

2015

In 2015, Black Lives Matter demonstrated against the deaths of numerous African Americans by police actions, including those of Charley Leundeu Keunang, Tony Robinson, Anthony Hill, Meagan Hockaday, Eric Harris, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, William Chapman, Jonathan Sanders, Sandra Bland, Samuel DuBose, Jeremy McDole, Corey Jones, and Jamar Clark as well Dylann Roof's murder of The Charleston Nine.[135][136]

In March, BLM protested at Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel's office, demanding reforms within the Chicago Police Department.[137] Charley Leundeu Keunang, a 43-year-old Cameroonian national, was fatally shot by Los Angeles Police Department officers. The LAPD arrested fourteen following BLM demonstrations.[138]

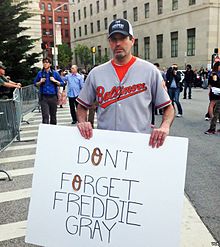

In April, Black Lives Matter across the United States protested over the death of Freddie Gray which included the 2015 Baltimore protests.[139][140] The National Guard was called in.[24] After the killing of Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina, Black Lives Matter protested Scott's death and called for Civilian oversight of police.[141]

In May, a protest by BLM in San Francisco was part of a nationwide protest, SayHerName, decrying the police killing of black women and girls, which included the deaths of Meagan Hockaday, Aiyana Jones, Rekia Boyd, and others.[142] In Cleveland, Ohio, after an officer was acquitted at trial in the Killing of Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams, BLM protested.[143] In Madison, Wisconsin, BLM protested after the officer was not charged in the killing of Tony Robinson.[144]

In June, after Dylann Roof's shooting in a historically black church in Charleston, South Carolina, BLM across the country marched, protested and held vigil for several days after the shooting.[145][146] BLM was part of a march for peace on the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge in South Carolina.[147] After the Charleston shooting, a number of memorials to the Confederate States of America were graffitied with "Black Lives Matter" or otherwise vandalized.[148][149] Around 800 people protested in McKinney, Texas after a video was released showing an officer pinning a girl—at a pool party in McKinney, Texas—to the ground with his knees.[150]

In July, BLM activists across the United States began protests over the death of Sandra Bland, an African-American woman, who was allegedly found hanged in a jail cell in Waller County, Texas.[151][152] In Cincinnati, Ohio, BLM rallied and protested the death of Samuel DuBose after he was shot and killed by a University of Cincinnati police officer.[153] In Newark, New Jersey, over a thousand BLM activists marched against police brutality, racial injustice, and economic inequality.[154] Also in July, BLM protested the death of Jonathan Sanders who died while being arrested by police in Mississippi.[155][156]

In August, BLM organizers held a rally in Washington, D.C., calling for a stop to violence against transgender women.[157] In Charlotte, North Carolina, after a judge declared a mistrial in the trial of a white Charlotte police officer who killed an unarmed black man, Jonathan Ferrell, BLM protested and staged die-ins.[158] In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Janelle Monáe, Jidenna, and other BLM activists marched through North Philadelphia to bring awareness to police brutality and Black Lives Matter.[159] Around August 9, the first anniversary of Michael Brown's death, BLM rallied, held vigil and marched in St. Louis and across the country.[160][161]

In September, over five hundred BLM protesters in Austin, Texas rallied against police brutality, and several briefly carried protest banners onto Interstate 35.[162] In Baltimore, Maryland, BLM activists marched and protested as hearings began in the Freddie Gray police brutality case.[163] In Sacramento, California, about eight hundred BLM protesters rallied to support a California State Senate bill that would increase police oversight.[164] BLM protested the killing of Jeremy McDole.[165]

In October, Black Lives Matter activists were arrested during a protest of a police chiefs conference in Chicago.[166] "Rise Up October" straddled the Black Lives Matter Campaign, and brought several protests.[167] Quentin Tarantino and Cornel West, participating in "Rise Up October", decried police violence.[168]

In November, BLM activists protested after Jamar Clark was shot by Minneapolis Police Department.[169] A continuous protest was organized at the Minneapolis 4th Precinct Police. During the encamped protest, protesters, and outside agitators clashed with police, vandalized the station and attempted to ram the station with an SUV.[170][171] Later that month a march was organized to honor Jamar Clark, from the 4th Precinct to downtown Minneapolis. After the march, a group of men carrying firearms and body armor[172] appeared and began calling the protesters racial slurs according to a spokesperson for Black Lives Matter. After protesters asked the armed men to leave, the men opened fire, shooting five protesters.[173][174] All injuries required hospitalization, but were not life-threatening. The men fled the scene only to be found later and arrested. The three men arrested were young and white, and observers called them white supremacists.[175][176] In February 2017, one of the men arrested, Allen Scarsella, was convicted of a dozen felony counts of assault and riot in connection with the shooting. Based in part on months of racist messages Scarsella had sent his friends before the shooting, the judge rejected arguments by his defense that Scarsella was "naïve" and sentenced him in April 2017 to 15 years out of a maximum 20-year sentence.[177][178]

From November into 2016, BLM protested the Murder of Laquan McDonald, calling for the resignation of numerous Chicago officials in the wake of the shooting and its handling. McDonald was shot 16 times by Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke.[179]

2016

In 2016, Black Lives Matter demonstrated against the deaths of numerous African Americans by police actions, including those of Bruce Kelley Jr., Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Joseph Mann, Abdirahman Abdi, Paul O'Neal, Korryn Gaines, Sylville Smith, Terence Crutcher, Keith Lamont Scott, Alfred Olango, and Deborah Danner, among others.

In January, hundreds of BLM protesters marched in San Francisco to protest the December 2, 2015, shooting death of Mario Woods, who was shot by San Francisco Police officers. The march was held during a Super Bowl event.[180] BLM held protests, community meetings, teach-ins, and direct actions across the country with the goal of "reclaim[ing] the radical legacy of Martin Luther King Jr."[181]

In February, Abdullahi Omar Mohamed, a 17-year-old Somali refugee, was shot and injured by Salt Lake City, Utah, police after allegedly being involved in a confrontation with another person. The shooting led to BLM protests.[182]

In June, members of BLM and Color of Change protested the California conviction and sentencing of Jasmine Richards for a 2015 incident in which she attempted to stop a police officer from arresting another woman. Richards was convicted of "attempting to unlawfully take a person from the lawful custody of a peace officer", a charge that the state penal code had designated as "lynching" until that word was removed two months prior to the incident.[183]

On July 5, Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old black man, was shot several times at point-blank range while pinned to the ground by two white Baton Rouge Police Department officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. On the night of July 5, more than 100 demonstrators in Baton Rouge shouted, "no justice, no peace," set off fireworks, and blocked an intersection to protest Sterling's death.[184] On July 6, Black Lives Matter held a candlelight vigil in Baton Rouge, with chants of "We love Baton Rouge" and calls for justice.[185]

On July 6, Philando Castile was fatally shot by Jeronimo Yanez, a St. Anthony, Minnesota police officer, after being pulled over in Falcon Heights, a suburb of St. Paul. Castile was driving a car with his girlfriend and her 4-year-old daughter as passengers when he was pulled over by Yanez and another officer.[186] According to his girlfriend, after being asked for his license and registration, Castile told the officer he was licensed to carry a weapon and had one in the car.[187] She stated: "The officer said don't move. As he was putting his hands back up, the officer shot him in the arm four or five times."[188] She live-streamed a video on Facebook in the immediate aftermath of the shooting. Following the fatal shooting of Castile, BLM protested throughout Minnesota and the United States.[189]

On July 7, a BLM protest was held in Dallas, Texas that was organized to protest the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. At the end of the peaceful protest, Micah Xavier Johnson opened fire in an ambush, killing five police officers and wounding seven others and two civilians. The gunman was then killed by a robot-delivered bomb.[190] Before he died, according to police, Johnson said that "he was upset about Black Lives Matter", and that "he wanted to kill white people, especially white officers."[191] Texas Lt. Governor Dan Patrick and other conservative lawmakers blamed the shootings on the Black Lives Matter movement.[192][193] The Black Lives Matter network released a statement denouncing the shootings.[194][195] On July 8, more than 100 people were arrested at Black Lives Matter protests across the United States.[196]

In the first half of July, there were at least 112 protests in 88 American cities.[197] On July 13, NBA stars LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul, and Dwyane Wade opened the 2016 ESPY Awards with a Black Lives Matter message.[198] On July 26, Black Lives Matter held a protest in Austin, Texas, to mark the third anniversary of the shooting death of Larry Jackson Jr.[199] On July 28, Chicago Police Department officers shot Paul O'Neal in the back and killed him following a car chase.[200] After the shooting, hundreds marched in Chicago, Illinois.[201]

In Randallstown, Maryland, near Baltimore, on August 1, police officers shot and killed Korryn Gaines, a 23-year-old African American woman, also shooting and injuring her son.[202] Gaines' death was protested in Baltimore.[203]

In August, Black Lives Matter protested in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania the death of Bruce Kelley Jr., who was shot after fatally stabbing a police dog while trying to escape from police the previous January.[204]

In August, several professional athletes began participating in National Anthem protests. The protests began in the National Football League (NFL) after Colin Kaepernick of the San Francisco 49ers sat during the anthem, as opposed to the tradition of standing, before his team's third preseason game of 2016.[205] During a post-game interview he explained his position stating, "I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder,"[206] a protest widely interpreted as in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.[207][208][209] The protests have generated mixed reactions and have since spread to other U.S. sports leagues.

In September, BLM protested the shooting deaths by police officers of Terence Crutcher in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, North Carolina.[210][211][212] The Charlotte Observer reported "The protesters began to gather as night fell, hours after the shooting. They held themed signs that said 'Stop Killing Us' and 'Black Lives Matter,' and they chanted 'No justice, no peace.' The scene was sometimes chaotic and tense, with water bottles and stones chucked at police lines, but many protesters called for peace and implored their fellow demonstrators not to act violently."[213] Multiple nights of protests in September and October were held in El Cajon, California, following the killing of Alfred Olango.[214][215]

2017

During the 2017 Black History Month, a month-long "Black Lives Matter" art exhibition was organized by three Richmond, Virginia artists at the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Richmond in the Byrd Park area of the city. The show featured more than 30 diverse multicultural artists on a theme exploring racial equality and justice.[216]

In the same month Virginia Commonwealth University's (VCU) James Branch Cabell Library focused on a month-long schedule of events relating to African-American history[217] and showed photos from the church's "Black Lives Matter" exhibition on its outdoor screen.[218] The VCU schedule of events also included: the Real Life Film Series The Angry Heart: The Impact of Racism on Heart Disease among African-Americans; Keith Knight presented the 14th Annual VCU Libraries Black History Month lecture; Lawrence Ross, author of the book Blackballed: The Black and White Politics of Race on America's Campuses talked about how his book related to the "Black Lives Matter" movement; and Velma P. Scantlebury, M.D., the first black female transplant surgeon in the United States, discussed "Health Equity in Kidney Transplantation: Experiences from a surgeon's perspective."

Black Lives Matter protested the killing of Jocques Clemmons which occurred in Nashville, Tennessee on February 10, 2017.[219] On May 12, 2017, a day after Glenn Funk, the district attorney of Davidson County decided not to prosecute police officer Joshua Lippert, the Nashville chapter of BLM held a demonstration near the Vanderbilt University campus all the way to the residence of Nashville mayor Megan Barry.[220][221]

On September 27 at the College of William & Mary, students associated with Black Lives Matter protested an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) event because the ACLU had fought for the right of the Unite the Right rally to be held in Charlottesville, Virginia.[222] William & Mary's president Taylor Reveley responded with a statement defending the college's commitment to open debate.[223][224]

2018

In February and March 2018, as part of its social justice focus, First Unitarian Church of Richmond, Virginia in Richmond, Virginia presented its Second Annual Black Lives Matter Art Exhibition.[225] Works of art in the exhibition were projected at scheduled hours on the large exterior screen (jumbotron) at Virginia Commonwealth University's Cabell Library. Artists with art in the exhibition were invited to discuss their work in the Black Lives Matter show as it was projected at an evening forum in a small amphitheater at VCU's Hibbs Hall. They were also invited to exhibit afterward at a local showing of the 1961 film adaptation of A Raisin in the Sun.

In April, CNN reported that the largest Facebook account claiming to be a part of the "Black Lives Matter" movement was a "scam" tied to a white man in Australia. The account, with 700,000 followers, linked to fundraisers that raised $100,000 or more, purportedly for U.S. Black Lives Matter causes; however, some of the money was instead transferred to Australian banks accounts, according to CNN. Facebook has suspended the offending page.[226][227][228]

2020

On February 23, 2020, Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed 25-year-old African American man, was murdered while jogging in Glynn County, Georgia.[229] Arbery had been pursued and confronted by three white residents driving two vehicles, including a father and son who were armed.[230] All three men were indicted on nine counts, including felony murder.[231]

On March 13, Louisville police officers knocked down the apartment door of 26-year-old African American Breonna Taylor, serving a no-knock search warrant for drug suspicions. After her boyfriend shot a police officer in the leg,[232] Police fired several shots which led to her death. Her boyfriend called 911 and said, "someone kicked in the door and shot my girlfriend".[233] Protests were held in Louisville with calls for police reform.[234]

George Floyd protests

At the end of May, spurred on by a rash of racially charged events including those above, over 450 major protests[235][236] were held in cities and towns across the United States and three continents.[237] The breaking point was due primarily to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin,[238] eventually charged with second-degree murder after a video circulated showing Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck for nearly nine minutes while Floyd pleaded for his life, repeating: "I can't breathe."[239][240] Following protesters' demands for additional prosecutions, three other officers were charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder.[241]

Black Lives Matter organized rallies in the United States and worldwide[242] from May 30 onwards,[243] with protesters enacting Floyd's final moments, many lying down in streets and on bridges, yelling "I can't breathe," while others marched by the thousands, some carrying signs that read, "Tell your brother in blue, don't shoot"—"Who do you call when the murderer wears a badge?" and "Justice for George Floyd."[244] While global in nature and supported by several unassociated organizations, the Black Lives Matter movement has been inextricably linked to these monumental protests.[245] Black Lives Matter called to "defund the police", a slogan with varying interpretations from police abolition to divestment from police and prisons to reinvestment in social services in communities of color.[246] In 2020, NPR reported that the Washington D.C. Black Lives Matter chapter's demands were defunding the police, halting the construction of new jails, decriminalizing sex work, removing police from schools, exonerating protesters and abolishing cash bail in Maryland.[247]

On June 5, Washington, D.C.'s Mayor Muriel Bowser announced that part of the street outside the White House had been officially renamed to Black Lives Matter Plaza posted with a street sign.[248]

On June 7, in the wake of global George Floyd protests and Black Lives Matter's call to "defund the police", the Minneapolis City Council voted to "disband its police department" to shift funding to social programs in communities of color. City Council President Lisa Bender said, "Our efforts at incremental reform have failed. Period." The council vote came after the Minneapolis Public Schools, the University of Minnesota and Minneapolis Parks and Recreation cut ties with the Minneapolis Police Department.[249] At the end of 2020, approximately $8 million of the city's $179 million police budget was reallocated for violence prevention pilot programs and was considered the type of incremental reform that activists and politicians had earlier denounced.[250]

On July 20, the Strike for Black Lives, organized in part by Black Lives Matter, featured thousands of workers across the United States performing a walkout to raise awareness of systemic racism following Floyd's murder.[251]

From May 26 to August 22, there were more than 7,750 BLM-linked demonstrations in over 2,240 locations throughout the United States.[252]

2021

On April 20, 2021, a jury, consisting of six white people and six people of color, found Chauvin guilty on three counts: unintentional second-degree murder; third-degree murder; and second-degree manslaughter.[253][254][255]

2022

In Illinois, Olivia Butts organized an effort to get the elimination of cash bail passed for 2023 under a new bill known as the SAFE-T Act.[256]

As a result of 2021 marijuana legalization efforts, Black Lives Matter activist Lexis Figuereo's conviction was expunged in New York.[257]

2023

A vigil was held for the death of Keenan Anderson who was killed by a police officer of the Los Angeles Police Department. Anderson was the cousin of Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors.[258] The releasing of camera footage regarding the death of Tyre Nichols in January 2023 led to protests in Memphis. Al Sharpton of the National Action Network spoke on the matter upon the release of bodycam footage.[259]

A ruling made by the Supreme Court of Alabama continues to prevent most police body camera footage, including that related to Joseph Pettaway who bled to death in 2018 after being bitten by a police dog, from being released to the public.[260][261] In December 2022 Judge Jerusha Adams again blocked the release of video footage related to Pettaways' death.[261]

International movement

In 2015, after the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland, black activists around the world modeled efforts for reform on Black Lives Matter and the Arab Spring.[60][262] This international movement has been referred to as the "Black Spring".[263][264] Connections have also been forged with parallel international efforts such as the Dalit rights movement.[265]

Australia

Following the death of Ms Dhu in police custody in August 2014, protests often made reference to the BLM movement.[266][267] In July 2016, a BLM rally was organized in Melbourne, Australia, which 3,500 people attended.[268] The protest also emphasized the issues of mistreatment of Aboriginal Australians by the Australian police and government.[269]

In May 2017, Black Lives Matter was awarded the Sydney Peace Prize, which "honours a nominee who has promoted 'peace with justice', human rights and non-violence".[270]

In early June 2020, soon after the George Floyd protests in the US, protests took place in Australia, with many of them focusing on the local issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody, racism in Australia and other injustices faced by Indigenous Australians.[271] Cricketer Michael Holding criticized Australia, as well as England, for refusing to take a knee in support of Black Lives Matter during cricket matches.[272][273]

Brazil

Blacks in Brazil suffer from economic marginalization, state violence, discrimination, and lower life-expectancy.[274] In June 2020, two Black children, 5-year-old Miguel Otávio Santana da Silva and 14-year-old João Pedro Matos Pinto, died in Brazil.[274] Miguel Otávio Santana da Silva was under the watch of the white boss of his mother when he fell off the balcony of a building.[274] João Pedro Matos Pinto was shot in the back by police in Rio de Janeiro during a raid where the police discharged seventy shots.[274][275] He was killed the same week as George Floyd.[276] Their deaths prompted protests in cities across the country.[274] The slogan "Black Lives Matter" was translated to "Vidas Negras Importam" in Portuguese.[274] Protests continued throughout 2020 and were renewed at the end of the year after supermarket security guards beat 40-year-old welder João Alberto Silveira Freitas to death in Porto Alegre.[277]

Canada

In July 2015, BLM protesters shut down Allen Road in Toronto, Ontario, protesting the shooting deaths of two black men in the metropolitan area—Andrew Loku and Jermaine Carby—at the hands of police.[278] In September, BLM activists shut down streets in Toronto, citing police brutality and solidarity with "marginalized black lives" as reason for the shutdown. Black Lives Matter was a featured part of the Take Back the Night event in Toronto.[279]

In June 2016, Black Lives Matter was selected by Pride Toronto as the honored group in that year's Pride parade, during which they staged a sit-in to block the parade from moving forward for approximately half an hour.[280] They issued several demands for Pride to adjust its relationship with LGBTQ people of color, including stable funding and a suitable venue for the established Blockorama event, improved diversity in the organization's staff and volunteer base, and that Toronto Police officers be banned from marching in the parade in uniform.[281] Pride executive director Mathieu Chantelois signed BLM's statement of demand, but later asserted that he had signed it only to end the sit-in and get the parade moving, and had not agreed to honor the demands.[282] In late August 2016, the Toronto chapter protested outside the Special Investigations Unit in Mississauga in response to the death of Abdirahman Abdi, who died during an arrest in Ottawa.[283]

In 2020, the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet and the killing of D'Andre Campbell in Canada sparked BLM protests demanding the defunding of police services.[284][285]

As of December 2020, there are five Canadian BLM chapters in Toronto, Vancouver, Waterloo Region, Edmonton, and New Brunswick.[284]

The other focal point of the Black Lives Matter movement in Canada is addressing issues, racism and other injustices faced by Indigenous Canadians.[286][287][288]

Denmark

In Denmark, an organization named Black Lives Matter Denmark was founded in 2016 by Bwalya Sørensen, a woman from Zambia who came to Denmark when she was 19 years old. The organization is centered around Sørensen and mainly focuses on rejected asylum seekers and criminal foreigners, sentenced to expulsion from Denmark.[289] The connection to the U.S. organization is unclear, but Sørensen has said she was encouraged by someone in the U.S. to start a Danish chapter, and that she, in 2017, was visited by the U.S. co-founder, Opal Tometi.[290]

In June 2020, following the murder of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter Denmark held a demonstration in Copenhagen that attracted 15,000 participants. Following the demonstration, the organization and Sørensen, in particular, received much criticism because rules separated people by ethnicity: at the demonstration, only black people could be in front, and white people were disallowed to participate in some chants.[291][292] Other controversies included Sørensen refusing to co-host a demonstration with Amnesty International because their employees were white,[293] and illegally raising money, while calling the missing fundraising permit peaceful "civil disobedience".[294] Sørensen herself has been criticized for splitting the movement with her confrontational style.[289][295]

A new organization, named Afro Danish Collective, was announced in June 2020, with Roger Matthisen, former member of the Folketing for The Alternative, as spokesperson. The organization has similar goals as Black Lives Matter Denmark, but will take a more moderate approach, including not distinguishing between people at demonstrations based on their skin color.[296][290] Matthisen said Afro Danish Collective was in part established because the leadership of Black Lives Matter Denmark had not been professional enough.[296]

France

On July 18, 2020, thousands of protesters marched near Paris to commemorate the fourth anniversary of the death of Adama Traoré. Traoré, a black man, was arrested in July 2016 and fainted after being pinned to the ground by police officers. He later died at a police station; the circumstances of his death are unclear.[297] Racial tensions continued with unrest in 2023 after the killing of teenager Nahel Merzouk.

Germany

On June 6, 2020, tens of thousands of people gathered across Germany to support the Black Lives Matter movement.[298] On July 18, 2020, more than 1,500 protesters participated in an anti-racism march in Berlin to condemn police brutality.[297]

Japan

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, several demonstrations took place in Japan, including a 1,000-person demonstration in Osaka on June 7, 2020,[299] and a 3,500-person march through the streets of Shibuya and Harajuku areas of Tokyo on June 14, 2020.[300] The movement has been met with some backlash in the country, notably on the internet,[301] where some users criticized tennis player Naomi Osaka after she encouraged people to join a Black Lives Matter march in the city of Osaka.[302]

New Zealand

On June 1, 2020, several BLM solidarity protests in response to the murder of George Floyd were held in several New Zealand cities including Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin, Tauranga, Palmerston North and Hamilton.[303][304][305][306] The Auckland event, which attracted between 2,000 and 4,000 participants, was organized by several members of New Zealand's African community. Auckland organizer Mahlete Tekeste, African American expatriate Kainee Simone, and sportsperson Israel Adesanya compared racism, mass incarceration, and police violence against African Americans to the over-representation of Māori and Pacific Islanders in New Zealand prisons, the controversial armed police response squad trials, and existing racism against minorities in New Zealand including the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings. Hip hop artist and music producer Mazbou Q also called on Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to condemn violence against black Americans.[307]

The left-wing Green Party, a member of the Labour-led coalition government, has also expressed support for the Black Lives Matter movement, linking the plight of African Americans to the racism, inequality, and higher incarceration rate experienced by the Māori and Pasifika communities. The BLM protests in New Zealand attracted criticism from Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters for violating the country's COVID-19 pandemic social distancing regulations banning mass gatherings of over 100 people.[308]

United Kingdom

Black Lives Matter emerged as a movement in the UK in the summer of 2016. Thousands attended protests against police racism in Manchester on July 11, and a group called Black Lives Matter UK (UKBLM) was set up in the wake of the June 23 Brexit referendum at a meeting addressed by US BLM activist Patrisse Cullors.[309][310][311][312] On August 4, 2016, BLM protesters blocked London City Airport in London, England. Several demonstrators chained themselves together on the airport's runway.[313][314] Nine people were arrested in connection with the incident. There were also BLM-themed protests in other English cities including Birmingham and Nottingham. The UK-held protests marked the fifth anniversary of the shooting death of Mark Duggan.[315]

In 2016, tabloid newspapers ran several stories seeking to expose and discredit BLM activists, leading the movement to adopt anonymity.[312] On June 25, 2017, BLM supporters protested in Stratford, London over the death of Edson Da Costa, who died in police custody. There were no arrests made at the protest.[316][317] According to Patrick Vernon, BLM's start in the UK in 2016 was not met with respect. From 2018 onwards, after events like the Grenfell Tower fire and the Windrush scandal, the movement was viewed more favorably by black Britons, in particular senior black Britions.[318] In December 2019, Black Lives Matter UK worked with the coalition Wretched of the Earth to represent the voices of global indigenous peoples and people of color in the climate justice movement.[319]

In 2020, protests were held in support of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US. Following the murder of George Floyd, London protests took place in Trafalgar Square on May 31, Hyde Park on June 3, Parliament Square on June 6, and outside the US Embassy on June 7. Similar protests took place in Manchester, Bristol, and Cardiff.[320] The UK protests not only showed solidarity with U.S. protesters, but also commemorated black people who have died in the UK, with protesters chanting, carrying signs, and sharing social media posts with names of victims including Julian Cole,[321] Belly Mujinga,[322] Nuno Cardoso,[323] and Sarah Reed.[324]

On June 7, protests continued in many towns and cities.[325] During a Black Lives Matter protest in Bristol, the city center statue of Edward Colston, a late 17th early 18th-century philanthropist, politician and slave trader, was pulled down by protesters, rolled along the road and pushed into Bristol Harbour.[326] The act was later condemned by Home Secretary Priti Patel who said: "This hooliganism is utterly indefensible."[327] In London, after it was defaced a few days earlier,[328] protesters defaced the statue of Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, Westminster with graffiti for a second time. Black spray paint was sprayed over his name and the words "was a racist" were sprayed underneath.[327] A protester also attempted to burn the Union Jack flag flying at the Cenotaph, a memorial to Britain's war dead.[329] Later in the evening violence broke out between protesters and police. A total of 49 police officers were injured after demonstrators threw bottles and fireworks at them.[330] Over the weekend, a total of 135 arrests were made by police.[325] British Prime Minister Boris Johnson commented on the events, saying "those who attack public property or the police – who injure the police officers who are trying to keep us all safe – those people will face the full force of the law; not just because of the hurt and damage they are causing, but because of the damage they are doing to the cause they claim to represent."[331]

Peaceful protests took place in Leeds' Millennium Square on June 14, 2020[332] organized by a coalition of organizations: Black Voices Matter', which included Black Lives Matter Leeds.[333] A second protest was held on Woodhouse Moor on June 21, organized by Black Lives Matter Leeds.[334]

On June 28, Black Lives Matter UK faced criticism for making a series of tweets from their verified Twitter account regarding Israel, including one that claims "mainstream British politics is gagged of the right to critique Zionism".[335] The Premier League, who were carrying the Black Lives Matter logo on their football shirts for the rest of the 2019–20 season, subsequently said that attempts by groups to hijack the cause to suit their own political ends are entirely unwelcome.[336] After receiving considerable donations in summer 2020, Black Lives Matter UK formalised its organisation.[312] In September 2020, the group changed its official name to Black Liberation Movement UK and became legally registered as a community benefit society.[337] However, the group still uses the Black Lives Matter name in its global cooperative efforts.[338] In January 2021, the Black Liberation Movement began to distribute its funds to grassroots black-led and anti-racist organisations across the UK.[339] Activists from a different BLM group, Charles Gordon[340] and Sasha Johnson, founded the Taking The Initiative Party (TTIP) in the summer of 2020 had applied to register as a political party through the Electoral Commission; however, BLM UK said "BLM UK has no intention to set up a political party. This person or group is not affiliated with us."[338]

In September 2021, British businessman and philanthropist Ken Olisa revealed to Channel 4 that Elizabeth II and the British royal family are supporters of Black Lives Matter.[341] In response, a spokesperson for Black Lives Matter UK said "We were surprised to learn the Queen is a BLM supporter. But we welcome anyone that agrees with our goal of dismantling white supremacy. Of course, actions speak louder than words. The Queen sits on a throne made from colonial plunder. Until she gives back all the stolen gold and diamonds from the Commonwealth and pays reparations, these are nothing more than warm words."[342]

In October 2021, The Guardian and The Times reported that a covert police unit in South Wales attempted to recruit a Black Lives Matter protester to be an informant and supply further information about far-right activists who had marched in support of Black Lives Matter.[343][344] In February 2022, the Swansea chapter of BLM announced it would be closing due to "attempted recruitment by the police and threats to its members' physical and mental safety from far-right activists".[345]

In July 2024, the Black Lives Matter UK Festival of Collective Liberation took place at Friends House, London, attended by more than 600 activists and supporters.[346][347]

2016 United States presidential election

Primaries

Democrats

At the Netroots Nation Conference in July 2015, dozens of Black Lives Matter activists took over the stage at an event featuring Martin O'Malley and Bernie Sanders. Activists, including Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors, asked both candidates for specific policy proposals to address deaths in police custody.[348] The protesters chanted several slogans, including "if I die in police custody, burn everything down" and "Shut this crap down".[349][24] The expression "Shut it down" would go on to become a popular phrase in Black Lives Matter protests and on social media.[24]

After conference organizers pleaded with the protesters for several minutes, O'Malley responded by pledging to release a wide-ranging plan for criminal justice reform. Protesters later booed O'Malley when he stated "Black lives matter. White lives matter. All lives matter."[349] O'Malley later apologized for his remarks, saying that he did not mean to disrespect the black community.[349]

On August 8, 2015, a speech by Democratic presidential candidate and civil rights activist Bernie Sanders was disrupted by a group who would go on to found the Seattle Chapter of Black Lives Matter including chapter co-founder Marissa Johnson[350] who walked onstage, seized the microphone from him and called his supporters racists and white supremacists.[351][352][353] Sanders issued a platform in response.[354] Nikki Stephens, the operator of a Facebook page called "Black Lives Matter: Seattle" issued an apology to Sanders' supporters, claiming these actions did not represent her understanding of BLM. She was then sent messages by members of the Seattle Chapter which she described as threatening and was forced to change the name of her group to "Black in Seattle". The founders of Black Lives Matter stated that they had not issued an apology.[355] In August 2015, the Democratic National Committee passed a resolution supporting Black Lives Matter.[356]

In the first Democratic primary debate, the presidential candidates were asked whether black lives matter or all lives matter.[357] In reply, Bernie Sanders stated, "Black lives matter."[357] Martin O'Malley said, "Black lives matter," and that the "movement is making is a very, very legitimate and serious point, and that is that as a nation we have undervalued the lives of black lives, people of color."[358] In response, Hillary Clinton pushed for criminal justice reform, and said, "We need a new New Deal for communities of color."[359] Jim Webb, on the other hand, replied: "As the president of the United States, every life in this country matters."[357] Hillary Clinton was not directly asked the same question, but was instead asked: "What would you do for African Americans in this country that President Obama couldn't?"[360] Clinton had already met with Black Lives Matter representatives, and emphasized what she described as a more pragmatic approach to enacting change, stating "Look, I don't believe you change hearts. I believe you change laws". Without policy change, she felt "we'll be back here in 10 years having the same conversation."[361] In June 2015, Clinton used the phrase "all lives matter" in a speech about the opportunities of young people of color, prompting backlash that she may misunderstand the message of "Black Lives Matter."[362][363]

A week after the first Democratic primary debate was held in Las Vegas, BLM launched a petition targeted at the DNC and its chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz demanding more debates, and "specifically for a #BlackLivesMatter themed Presidential debate."[364][365] The petition received over 10,000 signatures within 24 hours of being launched,[366] and had over 33,000 signatures as of October 27, 2015.[367] The DNC said that it would permit presidential candidates to attend a presidential town hall organized by activists, but that it would not add another debate to its official schedule.[368] In response, the organization released a press statement on its Facebook page stating that "[i]n consultation with our chapters, our communities, allies, and supporters, we remain unequivocal that a Presidential Town Hall with support from the DNC does not sufficiently respond to the concerns raised by our members", continuing to demand a full additional debate.[366]

After the first debate, in October 2015, a speech by Hillary Clinton on criminal justice reform and race at Atlanta University Center was interrupted by BLM activists.[369]

In February 2016, two Black Lives Matter activists protested at a private fundraiser for Clinton about statements she made in 1996 in which she referred to young people as "super-predators". One of the activists wanted Clinton to apologize for "mass incarceration" in connection with her support for her husband, then-President Bill Clinton's 1994 criminal reform law.[370]

Republicans

Republican candidates have been mostly critical of BLM. In August 2015, Ben Carson, the only African American vying for the Republican nomination for the presidency, called the movement "silly".[371] Carson also said that BLM should care for all black lives, not just a few.[372] In the first Republican presidential debate, which took place in Cleveland, one question referenced Black Lives Matter.[373] In response to the question, Scott Walker advocated for the proper training of law enforcement[373] and blamed the movement for rising anti-police sentiment,[374] while Marco Rubio was the first candidate to publicly sympathize with the movement's point of view.[375]

In August 2015, activists chanting "Black Lives Matter" interrupted the Las Vegas rally of Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush.[376] As Bush exited early, some of his supporters started responding to the protesters by chanting "white lives matter" or "all lives matter".[377]

Several conservative pundits have labeled the movement a "hate group".[378] Candidate Chris Christie, the New Jersey Governor, criticized President Obama for supporting BLM, stating that the movement calls for the murder of police officers.[379] Christie's statement was condemned by New Jersey chapters of the NAACP and ACLU.[380]

BLM activists also called on the Republican National Committee to have a presidential debate focused on issues of racial justice.[381] The RNC, however, declined to alter their debate schedule, and instead also supported a townhall or forum.[368]

In November 2015, a BLM protester was physically assaulted at a Donald Trump rally in Birmingham, Alabama. In response, Trump said, "maybe he should have been roughed up because it was absolutely disgusting what he was doing."[382] Trump had previously threatened to fight any Black Lives Matter protesters if they attempted to speak at one of his events.[383]

In March 2016, Black Lives Matter helped organize the 2016 Donald Trump Chicago rally protest that forced Trump to cancel the event.[384][385] Four individuals were arrested and charged in the incident; two were "charged with felony aggravated battery to a police officer and resisting arrest", one was "charged with two misdemeanor counts of resisting and obstructing a peace officer", and the fourth "was charged with one misdemeanor count of resisting and obstructing a peace officer".[386] A CBS reporter was one of those arrested outside the rally. He was charged with resisting arrest.[387]

General election

A group called Mothers of the Movement, which includes the mothers of Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, and other mothers whose "unarmed African American children have been killed by law enforcement or due to gun violence,"[388] addressed the 2016 Democratic National Convention on July 26.[389][390]

Commenting on the first of 2016 presidential debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, some media outlets characterized Clinton's references to implicit bias and systemic racism[391] as speaking "the language of the Black Lives Matter movement,"[392] while others pointed out neither Clinton nor Trump used the words "Black Lives Matter."[393]

In a Washington Post op-ed, DeRay Mckesson endorsed Hillary Clinton, because her "platform on racial justice is strong". He articulated that voting alone is not the only way to bring about "transformational change". He said that "I voted my entire life, and I was still tear-gassed in the streets of St. Louis and Baltimore. I voted my entire life, and those votes did not convict the killers of Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray or Michael Brown".[394][395]

2024 United States presidential election

In July 2024, Black Lives Matter released a statement opposing the Democratic Party's decision to nominate Kamala Harris for president without a primary election, describing the process as "anointing" Harris as the nominee without a public vote.[396][397] The organization argued that installing Harris as the Democratic nominee without a primary vote undermined democratic principles, stating that such a move "would make the modern Democratic Party a party of hypocrites."[398] BLM called on the Democratic National Committee to host a virtual primary to allow voter participation in the nomination process.[399]

BLM's stance sparked discussions about transparency and democratic engagement within the Democratic Party ahead of the 2024 presidential election.[397] The organization reiterated its call for a more open process, expressing concerns about the potential lack of representation and accountability in the nomination procedure.[400]

Reactions and legacy

The United States population's perception of Black Lives Matter has varied consistently and considerably by race and political affiliation.[401][402] A majority of Americans disapproved of the movement through 2018, after which it started gaining wider support. Black Lives Matter's popularity surged and reached its highest levels yet in the summer of 2020, when a Pew Research Center poll found that 60% of white, 77% of Hispanic, 75% of Asian and 86% of African-Americans either strongly supported or somewhat supported BLM.[19] However, its popularity had declined considerably in September of the same year, when another Pew Research Center poll showed that its overall approval ratings among all American adults had gone down by 12 percentage points to 55%, and that 45% of whites, 66% of Hispanics and 69% of Asians now approved of it.[403] Support remained widespread among black-American adults at 87%.[403]

A Politico-Morning Consult poll done in September 2020 as well as a Civiqs poll conducted in November 2021 had also found declining support for the movement.[404][405] A 2022 YouGov poll found declining support for BLM among African-Americans.[20] An April 2023 Pew Research Center poll found that only 51% of Americans supported the BLM movement, while 46% opposed the movement. In the same poll, 81% of African Americans said they still supported the movement.[18]

The phrase "All Lives Matter" sprang up as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement, but has been criticized for dismissing or misunderstanding the message of "Black Lives Matter".[406][407] Following the shooting of two police officers in Ferguson, the hashtag Blue Lives Matter was created by supporters of the police.[408] A few civil rights leaders have disagreed with tactics used by Black Lives Matter activists.[409][410] Public and academic debate at large has arisen over the structure and tactics used.[25]

While the vast majority of Democrats have voiced support for Black Lives Matter, few Republicans have done the same. President Donald Trump has been a vocal critic of Black Lives Matter, citing incidents of violence and looting at some Black Lives Matter protests. He has also used the protests as a means to promote law and order rhetoric and appealed to the grievances of some white people. Joe Biden, who ran against Trump in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, supported Black Lives Matter.[401]

In the weeks following the murder of George Floyd, many corporations came out in support of the movement, donating and enacting policy changes in accordance with the group's ethos.[411]

"All Lives Matter"

The phrase "All Lives Matter" sprang up as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement, shortly after the movement gained national attention.[407][412] Several notable individuals have supported All Lives Matter. Its proponents include Senator Tim Scott.[413] NFL cornerback Richard Sherman supports the All Lives Matter message, saying "I stand by what I said that All Lives Matter and that we are human beings."[414] According to an August 2015 telephone poll, 78% of likely American voters said that the statement "all lives matter" was closest to their own personal views when compared to "black lives matter" or neither. Only 11% said that the statement "black lives matter" was closest. Nine percent said that neither statement reflected their own personal point of view.[415]

According to professor David Theo Goldberg, "All Lives Matter" reflects a view of "racial dismissal, ignoring, and denial".[416] Professor Charles "Chip" Linscott said that "All Lives Matter" promotes the "erasure of structural anti-black racism and black social death in the name of formal and ideological equality and post-racial colorblindness".[130]

| External image | |

|---|---|

Co-founder Alicia Garza has responded to criticism of the movement's exclusivity, writing, "#BlackLivesMatter doesn't mean your life isn't important – it means that Black lives, which are seen without value within White supremacy, are important to your liberation."[417] President Barack Obama spoke about the debate between Black Lives Matter and All Lives Matter.[418] Obama said, "I think that the reason that the organizers used the phrase Black Lives Matter was not because they were suggesting that no one else's lives matter ... rather what they were suggesting was there is a specific problem that is happening in the African American community that's not happening in other communities." He also said "that is a legitimate issue that we've got to address."[75]

"Blue Lives Matter"

Blue Lives Matter is a countermovement in the United States supporting law enforcement officers and advocating that those who are prosecuted and convicted of killing law enforcement officers should be sentenced under hate crime statutes.[401][419] It was started in response to Black Lives Matter after the homicides of NYPD officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu in Brooklyn, New York on December 20, 2014.[420] Following the shooting of two police officers in Ferguson and in response to BLM, the hashtag #BlueLivesMatter was created by supporters of the police.[408] Following this, Blue Lives Matter became a pro-police officer movement in the United States, expanding after the killings of five police officers by a sniper in Dallas, Texas, who cited police shootings of Black people as his motive.[421][422][423]

Criticized by the ACLU and others, the movement inspired a state law in Louisiana that made it a hate crime to target police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical service personnel.[424][33]

The movement has been strongly criticized after the 2021 United States Capitol attack after pro-Trump rioters were seen showing support for the movement, with some bringing Blue Lives Matter flags to the protest. Many have called the movement hypocritical, as people in the mob assaulted Capitol police officers. One African American Capitol police officer, Harry Dunn, described being beaten with a Blue Lives Matter flag while rioters shouted racial slurs at him.[425][426] This has led some to argue that Blue Lives Matter is more about suppressing minorities than supporting law enforcement.[427][428][429]

"White Lives Matter"

White Lives Matter is an activist group created in response to Black Lives Matter. In August 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center added "White Lives Matter" to its list of hate groups.[430][431] The group has also been active in the United Kingdom.[432] The "White Lives Matter" slogan was chanted by torch-wielding alt-right protesters during the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. On October 28, 2017, numerous "White Lives Matter" rallies broke out in Tennessee. Dominated in Shelbyville particularly, protesters justified their movement in response to the increasing number of immigrants and refugees to Middle Tennessee.[433] "White Lives Matter" movements have also been present in European football, with instances of corresponding banners being raised at stadiums in the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Hungary, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.[434] White Lives Matter has also been promoted by white nationalists.[401]

Disinformation

The Anti-Defamation League reports numerous attempts to spread disinformation about BLM, citing as examples mid-June 2020 posts "featuring a sticker instructing people to 'kill a white on sight' spread on Facebook and Twitter. The sticker included the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #Antifa." On Telegram, a "white supremacist channel encouraged members to distribute the propaganda."[435] Another disinformation campaign, originating in June 2020 on 4chan, had the "goal of getting the hashtags #AllWhitesAreNazis (#AWAN) trending on Twitter. Organizers hoped to commandeer hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter and #BLM with a high volume of tweets—purportedly from Black activist accounts—containing the #AWAN hashtag." According to the ADL, the campaign's supporters hoped to sow tension and promote white supremacist accelerationism.[436][437]

Conservative pundits such as Ryan Fournier and Candace Owens have falsely claimed that ActBlue funnels donations intended for Black Lives Matter to Democratic candidates, with some going so far as to allege the organization is a money laundering scam.[438][439][440][441]

According to scholars, Russian operatives associated with the Internet Research Agency have engaged in a sustained campaign to simultaneously promote the Black Lives Matter movement as well as to oppose it. In some cases, Russian operatives encouraged antagonism and violence toward BLM members.[442]

Fake manifesto

In June 2020, an unknown party created a website at BLMManifesto.com purporting to be the manifesto of the BLM movement. The text mimics a 1919 Italian Fascist Manifesto, modified to relate to racial injustice. According to Snopes, the website appears intended to discredit the BLM movement.[443]

Statistics