Homer Defined

| "Homer Defined" | |

|---|---|

| The Simpsons episode | |

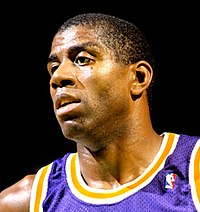

Homer attempts to avert the nuclear meltdown. Shadows and back-lighting were used in this scene to increase the tension. | |

| Episode no. | Season 3 Episode 5 |

| Directed by | Mark Kirkland |

| Written by | Howard Gewirtz |

| Production code | 8F04 |

| Original air date | October 17, 1991 |

| Guest appearances | |

| |

| Episode features | |

| Chalkboard gag | "I will not squeak chalk" (Bart squeaks the chalk while writing it)[1] |

| Couch gag | An alien is sitting on the couch and escapes through a trapdoor as the family rushes in.[2] |

| Commentary | Matt Groening Al Jean Mike Reiss Dan Castellaneta Howard Gewirtz Mark Kirkland |

"Homer Defined" is the fifth episode of the third season of the American animated television series The Simpsons. It originally aired on Fox in the United States on October 17, 1991.[3] In the episode, Homer accidentally saves the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant from meltdown by arbitrarily choosing the emergency override button using a counting rhyme. Homer is honored as a hero and idolized by his daughter Lisa, but feels unworthy of the praise, knowing his apparent heroism was blind luck. Meanwhile, Bart is downhearted after learning that Milhouse's mother forbids the boys to play together anymore because she thinks he is a bad influence on her son.

The episode was written by freelance writer Howard Gewirtz and directed by Mark Kirkland. Basketball player Magic Johnson of the Los Angeles Lakers made a guest appearance in the episode as himself, becoming the first professional athlete to do so on the show. He appears in two sequences, one in which he calls Homer to congratulate him on saving the plant, the second during a game sequence in which Lakers sportscaster Chick Hearn also guest stars.

The episode has received generally positive reviews from critics, particularly Johnson's appearance.

In its original airing on Fox, "Homer Defined" acquired a 12.7 Nielsen rating—the equivalent of being watched in approximately 11.69 million homes—and finished the week ranked 36th.

Plot

[edit]While eating donuts at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, Homer splatters jelly on the nuclear reactor core's temperature dial. The donut filling obscures the panel and the plant approaches a nuclear meltdown. Unable to remember his safety training (because he was playing with a Rubik's cube at the time), Homer chooses a button at random with a counting rhyme, which miraculously averts the meltdown. Springfield is saved and Homer is hailed as a hero.

Mr. Burns names Homer "Employee of the Month". Lisa, often embarrassed by her dim-witted dad, starts to worship him as a role model. Homer feels guilty that his so-called heroism was nothing but blind luck. His despair deepens after he receives a congratulatory phone call from Magic Johnson (who used the Lakers' last time out to call Homer personally), who tells him frauds are eventually exposed.

In the B-story, Bart is upset when he learns that he is not invited to Milhouse Van Houten's birthday party the other day because Milhouse's mother, Luann, thinks Bart is a bad influence and forbids the boys from being friends. Mad and Deprived of his best friend, a depressed Bart resorts to playing with Maggie. Marge visits Luann and persuades her to let the boys be friends again. Using the Krusty the Clown walkie-talkies Bart gave him for his birthday, Milhouse invites Bart to his house. Realizing that no one else would have stood up for him, Bart thanks Marge.

Burns introduces Homer to Aristotle Amadopolis (Jon Lovitz), the owner of the nuclear power plant in the fictional neighboring city of Shelbyville. Burns forces Homer to deliver a motivational speech to the Shelbyville workers. During Homer's fumbling address, an impending meltdown threatens the Shelbyville plant. In the control room, Amadopolis asks Homer to avert the disaster. Homer repeats his rhyme and blindly presses a button. Although Homer once more averts a meltdown, Amadopolis is irate to find that Homer's supposed heroism was by sheer dumb luck. Soon the phrase "to pull a Homer", meaning "to succeed despite idiocy," becomes a widely used catchphrase, even employed by Magic Johnson; its dictionary entry is illustrated by Homer's portrait.

Production

[edit]The episode was written by freelance writer Howard Gewirtz. It was one of many stories he pitched to the producers of the show.[4] According to executive producer Al Jean, Gewirtz's script ended up featuring one of the longest first acts (an act being the amount of time between commercial breaks) in the history of the show when the episode was completed.[5] Gewirtz's script originally contained two uses of the word "ass", once from Bart ("bad influence, my ass") and once from Burns ("... kiss my sorry ass goodbye"). This was the first time a character in the show had used this word, and it led to problems with the network censors.[5] Eventually, the censors forced the producers to remove one instance, so Burns’ line was changed to "kiss my sorry butt goodbye".[6] However, in the first rerun of the episode, this decision was reversed, with Burns saying "ass" and Bart saying "butt".[7] (The official DVD release and the Disney+ release contains the dialogue from the reruns.)

Basketball player Magic Johnson of the Los Angeles Lakers guest stars in the episode as himself. He was the first professional athlete to do so on the show.[8][9][10] Johnson appears in two sequences: first in a scene in which he calls to congratulate Homer on saving the plant,[11][12][13][14] and later in the episode during a basketball game when he "pulls a Homer" by accidentally getting the ball into the basket after slipping on the floor. The recording of the episode was done during the National Basketball Association's regular season, so the producers had a hard time scheduling Johnson's session. With the deadline approaching, the producers traveled to Johnson's home to record his lines.[5] According to the San Jose Mercury News, the recording equipment brought to his home did not work at first and "almost doomed the guest spot".[9] Lakers sportscaster Chick Hearn also guest stars in the episode, commentating on the game that Johnson plays.[3][5][15]

Another guest star in the episode was actor Jon Lovitz, who voiced Aristotle Amadopolis and an actor on a soap opera. This was Lovitz's third appearance on the show.[5] Amadopolis was modeled on the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis.[5] The character's dialogue was written to emulate Lovitz's comedic style, such as his talent for rapid mood swings.[5] Amadopolis returned a few episodes later in "Homer at the Bat", though in that episode he was voiced by cast member Dan Castellaneta rather than Lovitz.[16]

Milhouse's mother, Luann Van Houten, makes her first appearance in this episode. She was designed to look very similar to Milhouse.[5] Maggie Roswell was assigned to voice the character and she originally based it on Milhouse, who is voiced by Pamela Hayden. The producers felt her impression sounded out of place so she ended up using a more normal sounding voice.[6] It was Gewirtz who in this episode gave Milhouse his last name, Van Houten, which he got from one of his wife's friends.[4]

Director Mark Kirkland wanted the Springfield Power Plant to "look the best it had to date" and inserted shadows and back-lighting effects to make the panels in Homer's control room glow.[17]

During the scene in which Grandpa and the other residents of the retirement home are watching Wheel of Fortune, there was originally going to be a joke about comedian Redd Foxx, but because Foxx died six days before the episode aired, the joke was removed out of respect for Foxx and replaced with the Wheel bit at the last minute.

Reception and analysis

[edit]In its original airing on Fox, the episode acquired a 12.7 Nielsen rating and was viewed in approximately 11.69 million homes. It finished the week of October 14–20, 1991, ranked 36th, down from the season's average rank of 32nd.[18] It ranked second in its timeslot behind The Cosby Show, which finished 24th with a 15.5 rating. The episode tied with In Living Color as the highest rated show on Fox that week.[19]

"Homer Defined" has received generally positive reviews from critics. The authors of the book I Can't Believe It's a Bigger and Better Updated Unofficial Simpsons Guide, Warren Martyn and Adrian Wood, described it as an excellent episode which added new depth to the show in the scene with Marge trying to convince Luann to let Milhouse play with Bart again. They added that Lisa's "faith in her heroic father makes a nice change", and said that the episode's ending, in which Homer enters the dictionary, "is most satisfying".[2]

Colin Jacobson of DVD Movie Guide commented that after the episode "Bart the Murderer", this episode marks a regression, saying it was almost inevitable that it would not match up to the previous episode. He went on to say the subplot with Bart and Milhouse was more entertaining.[20] Nate Meyers of Digitally Obsessed rated the episode a 4 (of 5), writing that he enjoyed the Homer story but found the Bart and Milhouse subplot more interesting. He added that "Milhouse's mom won't allow him to play with Bart because she thinks Bart is a bad influence. It's rare for the show to allow Bart to feel genuine emotion, but there is plenty of it in this episode that makes for a nice character oriented story."[21]

Johnson's performance has also been praised. In 2004, ESPN released a list of the top 100 Simpsons sport moments, ranking his appearance at number 27.[22]Sports Illustrated listed Johnson's cameo as the fifth best athlete guest appearance on The Simpsons.[8] Meyers wrote that the episode "makes a lot of good points about the public making heroes in a rash, hysterical manner", and this point is made "with an amusing cameo by Earvin 'Magic' Johnson".[21]

The San Diego Union's Fritz Quindt said the animators "did [Johnson's] likeness good," and noted that in the game the "colors on the Lakers jerseys and the Forum court were correct. Chick Hearn and Stu Lantz were almost lifelike, announcing at courtside in Sunday-color-comics sweaters. And Chick's play-by-play was so real Stu couldn't get a word in."[23] Johnson's appearance was broadcast on CNN's Sports Tonight the day before the episode originally aired, and host Fred Hickman said he did not find it humorous.[23]

In his book Watching with The Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality, Jonathan Gray discusses a scene from "Homer Defined" that shows Homer reading a USA Today with the cover story: "America's Favorite Pencil – #2 is #1".[24] Lisa sees this title and criticizes the newspaper as a "flimsy hodge-podge of high-brass factoids and Larry King", to which Homer responds that it is "the only paper in America that's not afraid to tell the truth: that everything is just fine".[24][25] In the book, Gray says this scene is used by the show's producers to criticize "how often the news is wholly toothless, sacrificing journalism for sales, and leaving us not with important public information, but with America's Favorite Pencil".[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Groening, Matt (1997). Richmond, Ray; Coffman, Antonia (eds.). The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family (1st ed.). New York: HarperPerennial. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-06-095252-5. LCCN 98141857. OCLC 37796735. OL 433519M..

- ^ a b Martyn, Warren; Wood, Adrian (2000). "Homer Defined". BBC. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ a b Penner, Mike (September 22, 2009). "Cowboys' Owner May Be in Hot Water with Visitors". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Gewirtz, Howard (2003). The Simpsons season 3 DVD commentary for the episode "Homer Defined" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jean, Al (2003). The Simpsons season 3 DVD commentary for the episode "Homer Defined" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b Reiss, Mike (2003). The Simpsons season 3 DVD commentary for the episode "Homer Defined" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Reiss, Mike; Klickstein, Mathew (2018). Springfield confidential: jokes, secrets, and outright lies from a lifetime writing for the Simpsons. New York City: Dey Street Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-0062748034.

- ^ a b Whitaker, Lang (July 27, 2007). "The Simpsons' best sports star guest appearances". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ a b Brown, Daniel (July 22, 2007). "Eat My Sports: A Retrospective — Some Of The Sports World's Brightest Stars Knew They Hit It Big When They Guest-Starred On The Iconic Series". San Jose Mercury News. p. 1C.

- ^ Hervé, Par (December 14, 2009). "20 ans de sport chez les Simpsons". Les Dessous du Sport (in French). Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Sports Today". The Buffalo News. October 16, 1991. p. D2.

- ^ Yandel, Gerry (October 16, 1991). "TV Watch". The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution. p. E/9.

- ^ Rosenthal, Phil (October 16, 1991). "Washington Delivered A Historic Peep Show". Daily News of Los Angeles. p. L20.

- ^ "'Magic' On TV". Press-Telegram. October 17, 1991. p. C1.

- ^ Curtright, Guy (October 17, 1991). "Today's TV Tips". The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution. p. D/10.

- ^ Castellaneta, Dan (2003). The Simpsons season 3 DVD commentary for the episode "Homer Defined" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Kirkland, Mark (2003). The Simpsons season 3 DVD commentary for the episode "Homer Defined" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- ^ "World Series no strike Out in Nielsen". Lakeland Ledger. October 24, 1991. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ "Nielsen Ratings/Oct. 14–20". Long Beach Press-Telegram. Associated Press. October 23, 1991.

- ^ Jacobson, Colin. "The Simpsons: The Complete Third Season (1991)". DVD Movie Guide. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Meyers, Nate (June 23, 2004). "The Simpsons: The Complete Third Season". Digitally Obsessed. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Collins, Greg (January 23, 2004). "The Simpsons Got Game". ESPN. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ a b Quindt, Fritz (October 21, 1991). "Basically, CBS toys with unusual mix for Series success Magic has a cow, man On campus Tater tots". The San Diego Union. p. D–2.

- ^ a b c Gray, Jonathan (2006). Watching with The Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality. Taylor & Francis. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-415-36202-3.

- ^ "1 brush with fame for USA TODAY". USA Today. June 2, 2003. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

External links

[edit]