Siberian Husky

| Siberian Husky | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Black and white Siberian Husky | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | Chukcha[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common nicknames | Husky Sibe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | Siberia[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Siberian Husky is a medium-sized working sled dog breed. The breed belongs to the Spitz genetic family. It is recognizable by its thickly furred double coat, erect triangular ears, and distinctive markings, and is smaller than the similar-looking Alaskan Malamute.

Siberian Huskies originated in Northeast Asia where they are bred by the Chukchi people as well as the Koryak, Yukaghir and Kamchadal people of Siberia for sled pulling and companionship.[2][5] It is an active, energetic, resilient breed, whose ancestors lived in the extremely cold and harsh environment of the Siberian Arctic. William Goosak, a Russian fur trader, introduced them to Nome, Alaska, during the Nome Gold Rush, initially as sled dogs to work the mining fields and for expeditions through otherwise impassable terrain.[2] Today, the Siberian Husky is typically kept as a house pet, though they are still frequently used as sled dogs by competitive and recreational mushers.[6]

Lineage

In 2015, a DNA study indicated that the Siberian Husky, the Alaskan Malamute and the Alaskan husky share a close genetic relationship between each other and were related to Chukotka sled dogs from Siberia. They were separate to the two Inuit dogs, the Canadian Eskimo Dog and the Greenland Dog. In North America, the Siberian Husky and the Malamute both had maintained their Siberian lineage and had contributed significantly to the Alaskan husky, which was developed through crossing with European breeds.[7] Siberian Huskies show a genetic affinity with historical East Siberian dogs and ancient Lake Baikal dogs, and can be traced to a lineage which is over 9,500 years old.[8] A genomic sample of today's Siberian Husky has emerged into four genetically distinct populations: show dogs, pet dogs, racing sled dogs and Seppala Siberian Huskies.[5]

Several Arctic dog breeds, including the Siberian, show a significant genetic closeness with the now-extinct Taimyr wolf of North Asia due to admixture. These breeds are associated with high latitudes – the Siberian Husky and Greenland Dog, also associated with arctic human populations and to a lesser extent, the Shar-Pei and Finnish Spitz. There is data to indicate admixture of between 1 and 3% between the Taymyr wolf population and the ancestral dog population of these four high-latitude breeds. This introgression could have provided early dogs living in high latitudes with phenotypic variation beneficial for adaption to a new and challenging environment. It also indicates the ancestry of present-day dog breeds descends from more than one region.[9]

The Siberian Husky was originally developed by the Chukchi people of the Chukchi Peninsula in eastern Siberia.[10] They were brought to Nome, Alaska in 1908 to serve as working sled dogs, and were eventually developed and used for sled dog racing.[11][7]

Description

Coat

A Siberian Husky has a double coat that is thicker than that of most other dog breeds.[12] It has two layers: a dense, finely wavy undercoat and a longer topcoat of thicker, straight guard hairs.[13] It protects the dogs effectively against harsh Arctic winters, and also reflects heat in the summer. It is able to withstand temperatures as low as −50 to −60 °C (−58 to −76 °F). The undercoat is often absent during shedding. Their thick coats require weekly grooming.[12] An excessively long coat, sometimes referred to as a "wooly" or "woolie" coat, is considered a fault by the breed's standard as it lacks the thicker protection of the standard coat's guard hairs, obscures the dog's clear-cut outline, causes quicker overheating during serious harness work, and becomes easily matted and encrusted with snow and ice.[14]

Siberian Huskies come in a variety of colors and patterns, often with white paws and legs, facial markings, and tail tip. Example coat colors are black and white, copper-red and white, grey and white, pure white, and the rare "agouti" coat, though many individuals have blondish or piebald spotting. Some other individuals also have the "saddle back" pattern, in which black-tipped guard hairs are restricted to the saddle area while the head, haunches and shoulders are either light red or white. Striking masks, spectacles, and other facial markings occur in wide variety. All coat colors from black to pure white are allowed.[13][15][16][17] Merle coat patterns are not permitted by the American Kennel Club (AKC) and The Kennel Club (KC).[13][18] This pattern is often associated with health issues and impure breeding.[19]

Eyes

The American Kennel Club describes the Siberian Husky's eyes as "an almond shape, moderately spaced and set slightly obliquely". The AKC breed standard is that eyes may be brown, blue or black; one of each or particoloured are acceptable (complete is heterochromia). These eye-color combinations are considered acceptable by the American Kennel Club. The parti-color does not affect the vision of the dog.[20]

Nose

Show-quality dogs are preferred to have neither pointed nor square noses. The nose is black in gray dogs, tan in black dogs, liver in copper-colored dogs, and may be light tan in white dogs. In some instances, Siberian Huskies can exhibit what is called "snow nose" or "winter nose". This condition is called hypopigmentation in animals. "Snow nose" is acceptable in the show ring.[12][21]

Tail

Siberian Husky tails are heavily furred; these dogs will often curl up with their tails over their faces and noses in order to provide additional warmth. When curled up to sleep the Siberian Husky will cover its nose for warmth, often referred to as the "Siberian Swirl". The AKC recommends the tail should be expressive, held low when the dog is relaxed, and curved upward in a "sickle" shape when excited or interested in something.[12]

Size

The breed standard indicates that the males of the breed are ideally between 20 and 24 inches (51 and 61 cm) tall at the withers and weighing between 45 and 60 pounds (20 and 27 kg).[22] Females are smaller, growing to between 19 and 23 inches (48 and 58 cm) tall at the withers and weighing between 35 and 50 pounds (16 and 23 kg).[12] The people of Nome referred to Siberian Huskies as "Siberian Rats" due to their size of 40–50 lb (18–23 kg), versus the Alaskan Malamute's size of 75–85 lb (34–39 kg).[23]

Behavior

The Husky usually howls instead of barking.[24] They have been described as escape artists, which can include digging under, chewing through, or even jumping over fences.[4][25][26]

The ASPCA classifies the breed as good with children. It also states they exhibit high energy indoors, have special exercise needs, and may be destructive "without proper care".[4]

A 6 ft (1.83 m) fence is recommended for this breed as a pet, although some have been known to overcome fences as high as 8 ft (2.44 m).[26] Electric pet fencing may not be effective.[26] They need the frequent companionship of people and other dogs, and their need to feel as part of a pack is very strong.[27]

The character of the Siberian Husky is friendly and gentle.[28] A study found an association with a gene in the breed and impulsivity, inattention, and high activity.[29]

Siberian Huskies were ranked 77th out of 138 compared breeds for their intelligence by canine psychologist Stanley Coren.[30] However, the rankings in Coren's published work utilized only one of three defined forms of dog intelligence, "Working and Obedience Intelligence", which focused on trainability—a dog's ability to follow direction and commands in a direct context, specifically by trial judges in a controlled course setting.[31]

Health

A 2024 UK study found a life expectancy of 11.9 years for the breed compared to an average of 12.7 for purebreeds and 12 for crossbreeds.[32] Health issues in the breed are mainly genetic, such as seizures and defects of the eye (juvenile cataracts, corneal dystrophy, canine glaucoma and progressive retinal atrophy) and congenital laryngeal paralysis.[33] Hip dysplasia is not often found in this breed; however, as with many medium or larger-sized canines, it can occur.[34] The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals currently has the Siberian Husky ranked 155th out of a possible 160 breeds at risk for hip dysplasia, with only two percent of tested Siberian Huskies showing dysplasia.[35]

Siberian Huskies used for sled racing may also be prone to other ailments, such as gastric disease,[36] bronchitis or bronchopulmonary ailments ("ski asthma"),[37] and gastric erosions or ulcerations.[38]

The Siberian Husky is one of the more commonly affected breeds for X-linked progressive retinal atrophy. The condition is caused by a mutation in the RPGR gene in the breed.[39]

Modern Siberian Huskies registered in the US are almost entirely the descendants of the 1930 Siberia imports and of Leonhard Seppala's dogs, particularly Togo.[40] The limited number of registered foundational dogs has led to some discussion about their vulnerability to the founder effect.[41]

History

Prehistoric (prior to 1890s)

The Chukotka Sled Dog is considered the progenitor to the Siberian Husky. Developed by the Chukchi people of Russia, Chukotka sled dog teams have been used since prehistoric times to pulls sleds in harsh conditions, such as hunting sea mammals on oceanic pack ice.[42][43]

Origination of Name and Split from Chukotka Sled Dogs (1890s–1930s)

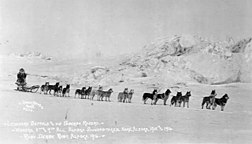

From the 1890s to the 1930s, sled dogs from northeast Siberia and especially Chukotka sled dogs were actively imported in vast numbers to Alaska, to transport gold miners to the Yukon, first as part of the Klondike Gold Rush,[42][5] then later the "All-Alaska Sweepstakes",[13] a 408-mile (657-km) distance dog sled race from Nome, to Candle, and back. At this time, "Esquimaux" or "Eskimo" was a common pejorative term for native Arctic inhabitants with many dialectal permutations including Uskee, Uskimay and Huskemaw. Thus dogs used by Arctic people were the dogs of the Huskies, the Huskie's dogs, and eventually simply the husky dogs.[44][45] Canadian and American settlers, not well versed on Russian geography, would distinguish the Chukotka imports by referring to them as Siberian huskies as Chukotka is part of Siberia.[42]

Smaller, faster and more enduring than the 100- to 120-pound (45- to 54-kg) freighting dogs then in general use, they immediately dominated the Sweepstakes race. Leonhard Seppala, the foremost breeder of Siberian sled dogs of the time, participated in competitions from 1909 to the mid-1920s with a number of championships to his name.[46]

On February 3, 1925, Gunnar Kaasen was the final musher in the 1925 serum run to Nome to deliver diphtheria serum from Nenana, over 600 miles to Nome. This was a group effort by several sled dog teams and mushers, with the longest (264 miles or 422 km) and most dangerous segment of the run covered by Leonhard Seppala and his sled team lead dog Togo. The event is depicted in the 2019 film Togo. A measure of this is also depicted in the 1995 animated film Balto; the name of Gunnar Kaasen's lead dog in his sled team was Balto, although unlike the real dog, Balto the character was portrayed as a wolf-dog in the film. In honor of this lead dog, a bronze statue was erected at Central Park in New York City. The plaque upon it is inscribed,

Dedicated to the indomitable spirit of the sled dogs that relayed antitoxin six hundred miles over rough ice, across treacherous waters, through Arctic blizzards from Nenana to the relief of stricken Nome in the winter of 1925. Endurance · Fidelity · Intelligence[46]

Siberian huskies gained mass popularity with the story of the "Great Race of Mercy", the 1925 serum run to Nome, featuring Balto and Togo. Although Balto is considered the more famous, being the dog that delivered the serum to Nome after running the final 53-mile leg, it was Togo who made the longest run of the relay, guiding his musher Leonhard Seppala on a 261-mile journey that included crossing the deadly Norton Sound to Golovin,[47] and who ultimately became a foundation dog for the Siberian Husky breed, through his progeny Toto, Molinka, Kingeak, Ammoro, Sepp III, and Togo II.[48]

In 1930, exportation of the dogs from Siberia was halted.[27] The same year saw recognition of the Siberian Husky by the American Kennel Club.[13] Nine years later, the breed was first registered in Canada. The United Kennel Club recognized the breed in 1938 as the "Arctic Husky", changing the name to Siberian Husky in 1991.[49] Seppala owned a kennel in Alaska before moving to New England, where he became partners with Elizabeth Ricker. The two co-owned the Poland Springs kennel and began to race and exhibit their dogs all over the Northeast. The kennel was sold to Canadian Harry Wheeler in 1931, following Seppala's return to Alaska[11]

The breed's foundation stock per records and studbooks consists of:

Kree Vanka (Male, 1930 Siberia Import)

Tserko (Male, 1930 Siberia Import),

Tosca (Female, Harry x Kolyma)

Duke (Male, also known as Chapman's Duke, reportedly Ici x Wanda)

Tanta of Alyeska (Female, Tuck x Toto)

Sigrid III of Foxstand (Female, Chenuk x Molinka)

Smokey of Seppala (Male, Kingeak x Pearl)

Sepp III (Male, Togo x Dolly)

Smoky (Male, unknown parentage)

Dushka (Female, Bonzo x Nanuk)

Kabloona (Female, Ivan x Duchess)

Rollinsford Nina of Marilyn (Female, Kotlik x Nera of Marilyn)[50][11]

As the breed was beginning to come to prominence, in 1933 Navy Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd brought about 50 Siberian Huskies with him on an expedition in which he hoped to journey around the 16,000-mile coast of Antarctica. Many of the dogs were bred and trained at Chinook Kennels in New Hampshire, owned by Eva Seeley. Called Operation Highjump, the historic trek proved the worth of the Siberian Husky due to its compact size and great speed.[46] Siberian Huskies also served in the United States Army's Arctic Search and Rescue Unit of the Air Transport Command during World War II.[51] Their popularity was sustained into the 21st century. They were ranked 16th among American Kennel Club registrants in 2012,[52] rising to 14th place in 2013.[53]

1940s-present

Huskies were extensively used as sled dogs by the British Antarctic Survey in Antarctica between 1945 and 1994.[54] A bronze monument to all of BAS's dog teams is outside its Cambridge headquarters, with a plaque listing all the dogs' names.[55]

In 1960, the US Army undertook a project to construct an under the ice facility for defense and space research, Camp Century, part of Project Iceworm involved a 150+ crew who also brought with them an unofficial mascot, a Siberian Husky named Mukluk.[56]

Due to their high popularity combining with their high physical and mental needs, Siberians are abandoned or surrendered to shelters at high rates by new owners who do not research them fully and find themselves unable to care for them. Many decide on the breed for their looks and mythos in pop culture, and purchase pups from backyard breeders or puppy mills who do not have breeder-return contracts that responsible breeders will, designed to keep the breed out of shelters.[57]

Sled dogs that were bred and kept by the Chukchi tribes of Siberia were thought to have gone extinct, but Benedict Allen, writing for Geographical magazine in 2006 after visiting the region, reported their survival. His description of the breeding practiced by the Chukchi mentions selection for obedience, endurance, amiable disposition, and sizing that enabled families to support them without undue difficulty.[43]

Traditional use and other activities

Originally, huskies were used as sled dogs in the polar regions. One can differentiate huskies from other dog types by their fast pulling-style. Modern racing huskies (also known as Alaskan huskies) represent an ever-changing crossbreed of the fastest dogs. Humans use huskies in sled-dog racing. Various companies have marketed tourist treks with dog sledges for adventure travelers in snow regions.[58] Huskies are also kept as pets, and groups work to find new pet homes for retired racing and adventure-trekking dogs.[59]

Many huskies, especially Siberian Huskies, are considered "working dogs" and often are high energy. Exercise is extremely important for the physical and mental health of these kinds of dogs and it can also prompt a strong bond between the owner and dog.[60] Since many owners now have huskies as pets in settings that are not ideal for sledding, other activities have been found that are good for the dog and fun for the owner.

- Rally Obedience: Owners guide their dogs through a course of difficult exercises side by side. There are typically 10 to 20 signs per course and involve different commands or tricks.[61]

- Agility Training: A fast-paced obstacle course that deals with speed and concentration. Dogs race the clock to complete the course correctly.[62]

- Skijoring is an alternative to sled pulling. The owner would be on skis while the dog would pull via a rope connected between the two.[63]

- Dog hiking is an alternative for owners who live near or are able to travel to a trail.[64] The owner travels with their dogs along trails in the wilderness. This activity allows the owner and dog to gain exercise without using the huskies' strong sense of pulling. Some companies make hiking equipment especially for dogs in which they may carry their own gear, including water, food, and bowls for each.

- Carting, also known as dryland mushing or sulky driving, is an urban alternative to dog sledding. Here, the dog can pull a cart that contains either supplies or an individual. This is also an acceptable way to use a dog's natural inclination to pull in an effective way.[65] These carts can be bought or handmade by the individual.

- Bikejoring is an activity where the owner bikes along with their dog while they are attached to their bike through a harness which keeps both the dog and owner safe. The dog or team of dogs can be attached to a towline to also pull the biker.[66]

In culture

- A bronze statue of Balto that has been displayed in New York City's Central Park since 1925 is one of the park's enduringly popular features.[67][68]

- The Twilight Saga, which features werewolves and the television series Game of Thrones spurred a huge uptick in demand for Siberian Huskies as pets, followed by a steep increase of their numbers at public shelters. Even though the animal actors were not Siberian Huskies, people were acquiring Siberian Huskies because they looked similar to the fictional direwolf characters depicted in the show.[69] Two of the show's stars pleaded with the public to stop acquiring the dogs without first researching the breed.[70]

- The phrase three dog night, meaning it is so cold you would need three dogs in bed with you to keep warm, originated with the Chukchi people of Siberia, who kept the Siberian husky landrace dog that became the modern purebred breed called the Siberian Husky.[71]

- The World War II Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943 was called "Operation Husky".[72]

- Several purebred Siberian Huskies portrayed Diefenbaker, the "half-wolf" companion to RCMP Constable Benton Fraser, in the CBS/Alliance Atlantis TV series Due South.[73]

- Siberian Huskies are the mascots of the athletic teams of several schools and colleges, including St. Cloud State University (St. Cloud State Huskies, Blizzard), Northern Illinois University (Northern Illinois Huskies, Victor),[74] the University of Connecticut (Connecticut Huskies, Jonathan), Northeastern University (Northeastern Huskies, Paws), the Michigan Technological University (Michigan Tech Huskies, Blizzard), University of Washington (Washington Huskies, Harry), Houston Baptist University (Houston Baptist Huskies, Kiza the Husky), and Saint Mary's University (Saint Mary's Huskies) and George Brown College (Toronto, Ontario).

See also

References

- ^ "Siberian husky". Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ a b c "Siberian husky | breed of dog". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ "American Kennel Club : Official Standard of the Siberian Husky" (PDF). Images.akc.org. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ a b c Sheldon L. Gerstenfeld (1 September 1999). ASPCA Complete Guide to Dogs. Chronicle Books. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8118-1904-6.

- ^ a b c Smith, Tracy; Srikanth, Krishnamoorthy; Huson, Heather (2024-08-21). "Comparative Population Genomics of Arctic Sled Dogs Reveals a Deep and Complex History" (PDF). Genome Biology and Evolution. 16 (9): 2–5 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ "Do many Siberian Huskies run the Iditarod? If not, why? – Iditarod". iditarod.com. 12 October 2020. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ a b Brown, S K; Darwent, C M; Wictum, E J; Sacks, B N (2015). "Using multiple markers to elucidate the ancient, historical and modern relationships among North American Arctic dog breeds". Heredity. 115 (6): 488–495. doi:10.1038/hdy.2015.49. PMC 4806895. PMID 26103948.

- ^ Feuerborn, Tatiana R.; Carmagnini, Alberto; Losey, Robert J.; Nomokonova, Tatiana; Askeyev, Arthur; Askeyev, Igor; Askeyev, Oleg; Antipina, Ekaterina E.; Appelt, Martin; Bachura, Olga P.; Beglane, Fiona; Bradley, Daniel G.; Daly, Kevin G.; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Murphy Gregersen, Kristian; Guo, Chunxue; Gusev, Andrei V.; Jones, Carleton; Kosintsev, Pavel A.; Kuzmin, Yaroslav V.; Mattiangeli, Valeria; Perri, Angela R.; Plekhanov, Andrei V.; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth; Shaymuratova, Dilyara; Smith, Oliver; Yavorskaya, Lilia V.; Zhang, Guojie; Willerslev, Eske; Meldgaard, Morten; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Larson, Greger; Dalén, Love; Hansen, Anders J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Frantz, Laurent (2021). "Modern Siberian dog ancestry was shaped by several thousand years of Eurasian-wide trade and human dispersal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (39): e2100338118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11800338F. doi:10.1073/pnas.2100338118. PMC 8488619. PMID 34544854. S2CID 237584023.

- ^ Skoglund, P.; Ersmark, E.; Palkopoulou, E.; Dalén, L. (2015). "Ancient Wolf Genome Reveals an Early Divergence of Domestic Dog Ancestors and Admixture into High-Latitude Breeds". Current Biology. 25 (11): 1515–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.019. PMID 26004765.

- ^ Fiszdon K, Czarkowska K. (2008). Social behaviours in Siberian huskies. Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW. Anim Sci 45: 19–28.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Bob (2015). Leonhard Seppala : the Siberian dog and the golden age of sleddog racing 1908–1941. Pat Thomas. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57510-170-5. OCLC 931927411.

- ^ a b c d e "AKC Meet The Breeds: Siberian Husky". AKC.org. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ^ a b c d e "Get to Know the Siberian Husky", 'The American Kennel Club', Retrieved 29 May 2014

- ^ "Siberian Husky Dog Breed Information". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- ^ "FCI-Standard N° 270 – Siberian Husky" (PDF). Federation Cynologique Internationale (AISBL). January 2000.

- ^ "Siberian Husky Breed Standard" (PDF). Canadian Kennel Club. January 2016.

- ^ "Siberian Husky Breed Standard". United Kennel Club.

- ^ "Siberian Husky Breed Standard". The Kennel Club. February 2017. Archived from the original on 2020-08-08. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ "Coat Color Identification Guidelines & Statement on "Merle" Patterning in Siberians". Siberian Husky Club of America Inc. September 2018. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ "American Kennel Club:Official Standard of the Siberian Husky" (PDF). American Kennel Club. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Common Husky Questions – Siberian Husky Club of Great Britain – Huskies UK". Siberianhuskyclub.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ "Siberian husky". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "The Siberian Husky: A Brief History of the Breed in America". Shca.org. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ^ "Siberian husky (breed of dog) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Lisa Duffy-Korpics (2009). Tales from a Dog Catcher. Globe Pequot. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-7627-5770-1.

- ^ a b c Diane Morgan (16 March 2011). Siberian Huskies For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1-118-05366-9.

- ^ a b DK Publishing (1 October 2013). The Dog Encyclopedia. DK Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-4654-2116-6.

- ^ "Official Valid Standard Siberian Husky". Federation Cynologique Internationale. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "DRD4 and TH gene polymorphisms are associated with activity, impulsivity and inattention in Siberian Husky dogs". ResearchGate. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Coren, Stanley (2006). The Intelligence of Dogs: A Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives or Our Canine Companions (1st ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-8087-7. OCLC 61461866.

- ^ "Canine Intelligence—Breed Does Matter | Psychology Today". Psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ McMillan, Kirsten M.; Bielby, Jon; Williams, Carys L.; Upjohn, Melissa M.; Casey, Rachel A.; Christley, Robert M. (2024-02-01). "Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death". Scientific Reports. 14 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10834484.

- ^ Monnet, Eric (2009). "Larageal paralysis" (PDF). AAHA/OVMA Toronto 2011 Proceedings. AAHA/OVMA Toronto 2011. March 24–27, 2011. Toronto, Canada. American Animal Hospital Association. pp. 443–445. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Your Siberian Husky: Its Hips and Its Eyes". Siberian Husky Club of America. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ "OFA: Hip Dysplasia Statistics". Offa.org. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Davis, M. S.; Willard, M. D.; Nelson, S. L.; Mandsager, R. E.; McKiernan, B. S.; Mansell, J. K.; Lehenbauer, T. W. (2003). "Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine – Journal Information". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 17 (3). Jvetintmed.org: 311–314. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(2003)017<0311:POGLIR>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Davis, M. S.; McKiernan, B.; McCullough, S.; Nelson Jr, S.; Mandsager, R. E.; Willard, M.; Dorsey, K. (2002). "Racing Alaskan Sled Dogs as a Model of "Ski Asthma" – Davis et al. 166 (6): 878 – American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 166 (6). Ajrccm.atsjournals.org: 878–882. doi:10.1164/rccm.200112-142BC. PMID 12231501. S2CID 34948487. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Davis, Michael S.; Willard, Michael D.; Williamson, Katherine K.; Steiner, Jörg M.; Williams, David A. (2005). "Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine – Journal Information". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 19 (1). Jvetintmed.org: 34–39. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19<34:SSEIIP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0891-6640. PMID 15715045.

- ^ Oliver, James A.C.; Mellersh, Cathryn S. (2020). "Genetics". In Cooper, Barbara; Mullineaux, Elizabeth; Turner, Lynn (eds.). BSAVA Textbook of Veterinary Nursing (Sixth ed.). British Small Animal Veterinary Association. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-910-44339-2.

- ^ Gay Salisbury; Laney Salisbury (17 February 2005). The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against an Epidemic. W. W. Norton. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-393-07621-9.

- ^ Alan H. Goodman; Deborah Heath; M. Susan Lindee (2003). Genetic Nature/culture: Anthropology and Science Beyond the Two-culture Divide. University of California Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-520-23793-3.

- ^ a b c Bogoslavskaya, Lyudmila (2010-03-01). "The Fan Hitch: Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog International". thefanhitch.org. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b "An iceman's best friend". Geographical. December 2006. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ^ Harper, Kenn (2007-09-28). "The Evolution of a Word Husky". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- ^ Dalziel, Hugh (1879). British dogs; their varieties, history, characteristics, breeding, management and exhibition. University of California Libraries. London, The bazaar office. pp. 205–213.

- ^ a b c Pisano, Beverly (1995). Siberian Huskies. TFH Publication. p. 8. ISBN 0-7938-1052-3.

- ^ Gay, Salisbury (2003), The cruelest miles : the heroic story of dogs and men in a race against an epidemic, Random House Audio, ISBN 0-553-52763-0, OCLC 671699744, retrieved 2021-10-02

- ^ Thomas, Bob (2015). Leonhard Seppala: the Siberian dog and the golden age of sleddog racing 1908–1941. Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57510-170-5. OCLC 931927411.

- ^ "Siberian Husky – Official Breed Standard". United Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ "Breeding Seppalas (5)". www.seppalakennels.com. Retrieved 2023-02-17.

- ^ "American Kennel Club – Siberian Husky History". Akc.org. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ "AKC Dog Registration Statistics". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ American Kennel Club 2013 Dog Registration Statistics Historical Comparisons & Notable Trends, The American Kennel Club, Retrieved 30 April 2014

- ^ Walton, Kevin; Atkinson, Rick (1996). Of Dogs and Men: Fifty Years in the Antarctic : the Illustrated Story of the Dogs of the British Antarctic Survey 1944 - 1994. Images. ISBN 189781755X.

- ^ "The British Antarctic Survey Husky Sledge Dog Monument unveiled". British Antarctic Survey. 7 July 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ "Proceedings – Did You Know – Camp Century". U.S. Coast Guard. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ Mary Robins. "How Game of Thrones has Impacted — And Hurt — Siberian Huskies". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ^ "How Sled Dogs Work". HowStuffWorks. 2008-01-14. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Keith, Christie (2011-02-18). "Lessons from a sled dog massacre". SFGATE. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "Siberian Husky Dog Breed Information". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "Getting Started in Rally". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ "Agility". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ "Skijoring Is Winter's Wildest Sport. Here's How to Do It". Bloomberg.com. 2018-01-12. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Gibeault, Stephanie (September 29, 2019). "Hiking With Your Dog: Tips For Hitting The Trail In A Safe And Fun Way". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Penny Leigh. "More Sports for All Dogs: Drafting & Carting". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Gemma Johnstone. "Bikejoring: Is This Adrenaline Inducing Sport Right For You and Your Dog?". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ "Central Park – Balto". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved 2014-11-18.

- ^ "Balto". Centralpark.com. 7 August 2017.

- ^ "In Game of Thrones fans' pursuit of real-life dire wolves, huskies may pay the price". National Geographic. May 6, 2019.

- ^ "'Game of Thrones' Star Jerome Flynn Speaks Up for Huskies". PETA. 11 April 2019.

- ^ Burroughs, William James (2005). Climate Change in Prehistory: The End of the Reign of Chaos. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-521-82409-5.

- ^ "Operation husky: Sicily – 9/10 July 1943". Combined Operations Command. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Ken Beck (1 April 2002). The Encyclopedia of TV Pets: A Complete History of Television's Greatest Animal Stars. Thomas Nelson Inc. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-1-4185-5737-9.

- ^ "About Mission". Northern Illinois University Alumni Association. Retrieved 2014-05-01.