Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Poitiers

Archdiocese of Poitiers Archidioecesis Pictaviensis Archidiocèse de Poitiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Ecclesiastical province | Poitiers |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 13,098 km2 (5,057 sq mi) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2021) 812,900 (est.) 661,000 (est.) (81.3%) |

| Parishes | 28 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | 3rd Century (as Diocese) 8 December 2002 (as Archdiocese) |

| Cathedral | Cathedral Basilica of St. Peter in Poitiers |

| Patron saint | St. Hilary of Poitiers |

| Secular priests | 150 (Diocesan) 5 (Religious Orders) 44 Permanent Deacons |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Sede vacante |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Pascal Wintzer |

| Suffragans | Angoulême La Rochelle and Saintes Limoges Tulle |

| Bishops emeritus | Albert Rouet Archbishop (2002–2011) |

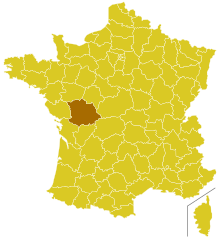

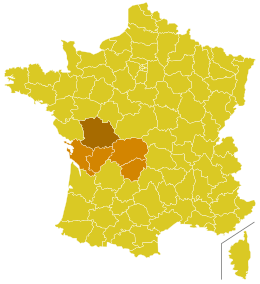

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| Website of the Archdiocese (French) | |

The Archdiocese of Poitiers (Latin: Archidioecesis Pictaviensis; French: Archidiocèse de Poitiers) is a Latin archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The archepiscopal see is in the city of Poitiers. The Diocese of Poitiers includes the two Departments of Vienne and Deux-Sèvres. The Concordat of 1802 added to the see besides the ancient Diocese of Poitiers a part of the Diocese of La Rochelle and Saintes.

The diocese was erected according to an unsteady tradition in the third century, as a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Bordeaux. On 13 August 1317, the diocese was subdivided by Pope John XXII, and two new dioceses, Luçon and Maillezais, were created.[1] The diocese was elevated to the rank of an archdiocese in 2002. The archdiocese is the metropolitan of the Diocese of Angoulême, the Diocese of La Rochelle, the Diocese of Limoges, and the Diocese of Tulle.

The Cathedral Church of Saint-Pierre had a chapter composed of the bishop and twenty-four canons. The officers of the chapter were: the dean, the cantor, the provost, the sub-dean, the sub-cantor, and the three archdeacons (who are not prebends). The abbé of Nôtre-Dame-le-Grand was also a member of the chapter ex officio.[2]

Before the Revolution, the diocese had three archdeacons: the archdeacon of Poitiers, the archdeacon of Briançay (or Brioux), and the archdeacon of Thouars.[3]

The current archbishop is Pascal Wintzer, who was appointed in 2012. Since 2010 there have been three priestly ordinations in the diocese, and four ordinations of permanent deacons.[4]

History

[edit]Louis Duchesne holds that its earliest episcopal catalogue represents the ecclesiastical tradition of Poitiers in the twelfth century.[5] The catalogue reckons twelve predecessors of Hilary of Poitiers, among them Nectarius, Liberius, and Agon, and among his successors Sts. Quintianus and Maxentius. Duchesne does not doubt the existence of the cults of these saints, but he questions whether they were bishops of Poitiers. In his opinion, Hilary (350 – 367 or 368) is the first bishop of whom we have historical evidence.[6] In this he concurs with the Benedictine editors of Gallia Christiana.[7]

Notable bishops

[edit]Among his successors were Arnauld d'Aux (1306–1312), made cardinal in 1312; Guy de Malsec (1371–1375), who became cardinal in 1375; Simon de Cramaud (1385–1391), indefatigable opponent of the antipope Benedict XIII, who became cardinal in 1413;[8] Louis de Bar (1394–95), cardinal in 1397 who administered the diocese (1413–1423); Jean de la Trémouille (1505–07), cardinal in 1507; Gabriel de Gramont (1532–1534), cardinal in 1507; Claude de Longwy de Givry (1538–1552), became cardinal in 1533; Antonio Barberini (1652–1657), cardinal in 1627; Abbé de Pradt (1805–1809), Chaplain of Consul Napoleon Bonaparte and afterwards Archbishop of Mechlin, Louis Pie (1849–1880), cardinal in 1879.

St. Emmeram was a native of Poitiers, but according to the Bollandists and Duchesne the documents which make him Bishop of Poitiers (c. 650) are not trustworthy.[9] On the other hand, Bernard Sepp,[10] while admitting that there is no evidence (at vero in catalogo episcoporum huius dioecesis nomen Emmerammi non occurrit...), nonetheless points out that there is space after the death of Dido and the accession of Ansoaldus for Emmeramus, that is, between 674 and 696.[11] Dom François Chamard, Abbot of Solesmes, claims that he did hold the see, and succeeded Didon, bishop about 666 or 668.[12]

Education at Poitiers

[edit]As early as 312 the bishop of Poitiers established a school near his cathedral; among its scholars were Hilary, St. Maxentius, Maximus, Bishop of Trier, and his two brothers St. Maximinus of Chinon and St. John of Marne, Paulinus, Bishop of Trier, and the poet Ausonius. In the sixth century Fortunatus taught there, and in the twelfth century students chose to study at Poitiers with Gilbert de la Porrée.

Bishop Gilbert de la Porrée attended the concilium generale which began at Reims on 21 March 1148 and continued for the rest of the month, under the presidency of Pope Eugenius III.[13] After the conclusion of the council, he was attacked in a papal consistory by Bernard of Clairvaux, always searching for heretics, schismatics and other deviants from his strict view of orthodoxy, for various heterodox theological opinions.[14] Gilbert demanded that he be judged on the basis of what he had written, not on what people believed that he had said, and he was able to argue each charge successfully against Bernard.[15] Pope Eugene ruled in Gilbert's favor, with the full agreement of the cardinals in attendance, and sent the bishop back to his diocese with his powers undiminished and in full honor.[16]

The University

[edit]Charles VII of France erected a university at Poitiers, which was his temporary capital, since he had been driven from Paris, in 1431.[17] The new foundation stood in opposition to Paris, where the city was in the hands of the English and the majority of the faculty had accepted Henry VI of England.[18] With a Bull of 28 May 1431, on the petition of Charles VII, Pope Eugene IV approved the new university and awarded it privileges similar to those of the University of Toulouse.[19] In the reign of Louis XII there were in Poitiers no less than four thousand students — French, Italians, Flemings, Scots, and Germans. There were ten colleges attached to the university. In 1540, at the Collège Ste. Marthe, the famous Classicist Marc Antoine Muret had a chair; Gregory XIII called him to Rome to work on his edition of the Septuagint, pronouncing him the torch and the pillar of the Roman School.[20] The famous Jesuit Juan Maldonado and five of his confrères went in 1570 to Poitiers to establish a Jesuit college at the request of some of the inhabitants.[21] After two unsuccessful attempts, the Jesuits were given the Collège Ste. Marthe in 1605. François Garasse was professor at Poitiers (1607–08), and had as a pupil Guez de Balzac. Garasse was well known for his violent polemics. He died of the plague at Poitiers in 1637.[22] Among other students at Poitiers were Achille de Harlay, President de Thou, the poet Joachim du Bellay, the chronicler Brantome Descartes, François Viète the mathematician, and Francis Bacon. In the seventeenth century the Jesuits sought affiliation with the university and in spite of the opposition of the faculties of theology and arts their request was granted. Jesuit ascendancy grew; they united to Ste. Marthe the Collège du Puygareau. Friction between them and the university was continuous, and in 1762 the general laws against them throughout France led to the Society being expelled from Poitiers and from France. Moreover, from 1674 the Jesuits had conducted at Poitiers a college for clerical students from Ireland.

In 1806 the State reopened the school of law at Poitiers and later the faculties of literature and science. These faculties were raised to the rank of a university in 1896. From 1872 to 1875 Cardinal Pie was engaged in re-establishing the faculty of theology. As a provisional effort he called to teach in his Grand Séminaire three professors from the Collegio Romano, among them Fr. Clement Schrader, S.J., formerly a professor at Vienna and the commentator of the Syllabus, who died at Poitiers in 1875.[23] The effort does not appear to have borne fruit, a casualty of the 1905 Law of the Separation of Church and State.[24]

Bishops

[edit]To 1000

[edit]- [? Agon][25]

- Hilary of Poitiers (349–367)[26]

- [Pascentius][27]

- [Quintianus]

- [Gelasius]

- [Anthemius]

- [Maigentius]

- Adelfius of Poitiers (533)[28]

- Daniel of Poitiers (attested 541)[29]

- Pientius 555 or 557–561[30]

- Pescentius 561[31]

- Maroveus (573–594)[32]

- Plato (594–599)[33]

- Venantius Fortunatus 599–610[34]

- Caregisile (before 614)

- Ennoald (614–616)[35]

- Johannes (John) I (attested 627)[36]

- Dido (Desiderius) (c. 629–c. 669)[37]

- Ansoald (c. 677 – after 697)[38]

- Eparchius[39]

- Maximinus[40]

- Gaubert

- Godon de Rochechouart (c. 757)[41]

- Magnibert

- Bertauld

- Benedict (Benoit)

- Johannes (John) (c. 800)[42]

- Bertrand I

- Sigebrand (c. 818)

- Friedebert (attested 834)[43]

- Ebroin (attested 838, 844, 848)[44]

- Engenold (860, 862, 871)[45]

- Frotier I (expelled)

- Hecfroi (attested 878 – 900)[46]

- Frotier II (c. 900 – 936)[47]

- Alboin c. 937

- Peter I (963–975)[48]

- Gislebert (c. 975 – after 1018)[49]

1000 to 1300

[edit]- Isembert I (c. 1021, 1028) (nephew of Bishop Gislebert)[50]

- Isembert II c. 1047 – 1086 (nephew of Bishop Isembert)[51]

- Peter II 22 February 1087 – 1117[52]

- Guillaume I Gilbert 1117–1124

- Guillaume II Adelelme (1 June 1124 – 6 October 1140)[53]

- Grimoard (1140 – 1142)[54]

- Gilbert de La Porrée (1142 – 4 September 1154)[55]

- Calo (attested 1155, 1157)[56]

- Laurent (26 March 1159 – 27/28 March 1161)[57]

- Jean aux Belles Mains 1162

- Guillaume Tempier (1184–1197)[58]

- Ademar du Peirat (1198)[59]

- Maurice de Blaron (1198 – 6 March 1214)[60]

- Guillaume Prévost (April 1214 – 1224)[61]

- Philippe Balleos (1224 – 8 February 1234)[62]

- Jean de Melun (1235 – 11 November 1257)[63]

- Hugo de Châteauroux (1259– 14 October 1271)[64]

- Gauthier de Bruges (4 December 1279 – 1306)[65]

1300 to 1500

[edit]- Arnaud d'Aux (4 November 1306 – December 1312)[66]

- Fort d'Aux (29 March 1314 – 8 March 1357)[67]

- Jean de Lieux (27 November 1357 – August 1362)[68]

- Aimery de Mons (4 June 1363 – 3 March 1370)[69]

- Guy de Malsec (Gui de Maillesec) (9 April 1371 – 1375)[70]

- Bertrand de Maumont (9 January 1376 – 12 August 1385)[71]

- Simon de Cramaud (24 November 1385 – 17 March 1391) (Avignon Obedience)[72]

- Louis de Bar (1391–1395) (Avignon Obedience)[73]

- Ythier de Mareuil (2 April 1395 – 1403) (Avignon Obedience)[74]

- Gérard de Montaigu (27 September 1403 – 24 July 1409) (Avignon Obedience)[75]

- Pierre Trousseau (11 September 1409 – 2 May 1413)[76]

- Cardinal Louis de Bar (3 March 1423 – 1424) (Administrator)[77]

- Hugo de Combarel (14 February 1424 – 1440)[78]

- Guillaume Gouge de Charpaignes (15 December 1441 – 1448)[79]

- Jacques Juvénal des Ursins (3 March 1449 – 12 March 1457)[80]

- Léon Guérinet (1457 – 29 March 1462)[81]

- Jean VI du Bellay (15 April 1462 – 3 September 1479)[82]

- Guillaume VI de Cluny (26 October 1479 – 1481)[83]

- Pierre d'Amboise (21 November 1481 – 1 September 1505)[84]

1500 to 1800

[edit]- Cardinal Jean-François de la Trémoille (5 December 1505 – July 1507) (Administrator)[85]

- Claude de Husson (1510–1521)[86]

- Louis de Husson (1521–1532)[87]

- Cardinal Gabriel de Gramont (Administrator) (13 January 1532 – 26 March 1534)[88]

- Cardinal Claude de Longwy de Givry (29 April 1534 – 15xx ?) (Administrator)[89]

- Jean d'Amoncourt (30 January 1551 – 1558)[90]

- Charles de Pérusse des Cars (13 March 1560 – 19 December 1569)[91]

- Jean du Fay, O.S.B. (3 March 1572 – died 5 November 1578)[92]

- Geoffroy de Saint-Belin (27 March 1578 – 21 November 1611)[93]

- Henri-Louis Chasteigner de La Roche-Posay (19 March 1612 – 30 July 1651)[94]

- Antonio Barberini (1652 – 1657)[95]

- Gilbert Clérembault de Palluau (1 April 1658 – 3 January 1680)[96]

- Hardouin Fortin de La Hoguette (15 July 1680 – 21 January 1692)[97]

- François-Ignace de Baglion de Saillant (23 November 1693 – 26 January 1698)[98]

- Antoine-Girard de La Bournat (15 September 1698 – 8 March 1702)[99]

- Jean-Claude de La Poype de Vertrieu (25 September 1702 – 3 February 1732)[100]

- Jean-Louis de Foudras de Courcenay (3 February 1732 – 13 August 1748)[101]

- Jean-Louis de La Marthonie de Caussade (21 April 1749 – 12 March 1759)[102]

- Martial-Louis de Beaupoil de Saint-Aulaire (9 April 1759 – 1798)[103]

From 1800

[edit]- Jean-Baptiste-Luc Bailly (1802–1804)[104]

- Dominique-Georges-Frédéric Dufour de Pradt (1804–1808)[105]

- Jean-Baptiste de Bouillé (1817–1842)[106]

- Joseph-Aimé Guitton (1842–1849)[107]

- Louis-François-Désiré-Edouard Pie (1849–1880)[108]

- Jacques-Edmé-Henri Philadelphe Bellot des Minières (1880 – 15 March 1888)[109]

- Augustin-Hubert Juteau (1889–1893)[110]

- Henri Pelgé (1894–1911)[111]

- Louis Humbrecht (1 September 1911 – 14 September 1918)[112]

- Olivier de Durfort de Civrac (1918 – 1932)[113]

- Edouard Mesguen 1933–1956

- Henri Vion 1956–1975

- Joseph Rozier 1975–1994

- Albert Rouet (first archbishop) 1994–2011

- Pascal Wintzer[114] since 2012[115]

References

[edit]- ^ Favreau and Pon, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Pouillé, p. 148, 160.

- ^ Pouillé, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Catholiques en Poitou: Site officiel du diocèse de Poitiers, Ordinations, retrieved: 2017-05-05.

- ^ Duchesne, p. 79, and see p. 82: "Tout ce qu'on peut dire, en somme, c'est que quelques-uns des premiers noms de la liste se retrouvent parmi ceux des saints que l'église de Poitiers honorait, soit qu'ils eussent vécu dans son sein, soit qu'elle en eût adopté le culte. De tout cela, il ne ressort pour notre liste aucune vérification sérieuse."

- ^ Duchesne, pp. 79–82.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 1138.

- ^ Kaminsky, Howard (1974). "The Early Career of Simon de Cramaud". Speculum. 49 (3): 499–534. doi:10.2307/2851753. JSTOR 2851753. S2CID 162820209.

- ^ S. Berger, "Poitiers," in: Encyclopédie des sciences religieuses, publ. sous la direction de F. Lichtenberger (in French). Vol. 10. Paris: G. Fischbacher. 1881. p. 661., points out that the inscription that gives his date of death as 662 belongs to the thirteenth century.

- ^ Bernardus Sepp, "Abeonis episcopi Frisingensis Vita S. Emmerammi authentica," Analecta Bollandiana VIII (Paris V. Palme 1889), 211-255.

- ^ Sepp, p. 221, note 2; but cf. p. 226 note 2.

- ^ Georges Goyau, "Poitiers," The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 12. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911), retrieved: 2017-05-03. May 2017. See: Brigitte Waché, "Les relations entre Duchesne et dom Chamard," in: Mgr Duchesne et son temps. Rome, (École Française de Rome, 1975) pp. 257–269.

- ^ P. Jaffé and S. Loewenfeld, Regesta pontificum Romanorum, II, pp. 52–53. Bishop Gilbert is addressed on April 14 in a papal mandate along with the other French bishops in attendance: Jaffé-Loewenfeld, no. 9240.

- ^ Nikolaus Häring (1966). Gilbert of Poitiers: The Commentaries on Boethius. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-88844-013-6.

- ^ K. J. Hefele, Histoire des conciles Tome VII (tr. Delarc) (Paris: Adrien Le Clere 1872), pp. 314–318.

- ^ The story is told in detail by Otto of Frising, in his Gesta Friderici Imperatoris, Book I, chapters 56 and 57, in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica Scriptorum Tomus XX (Hannover: Hahn 1868), pp. 382–384.

- ^ Jos. M. M. Hermans; Marc Nelissen (2005). Charters of Foundation and Early Documents of the Universities of the Coimbra Group. Leiden: Leuven University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-5867-474-6.

- ^ Hastings Rashdall (1895). The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages. Vol. II. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 191–193. ISBN 9780790580487.

- ^ Fournier, Statuts pp. 283–285.

- ^ Charles Dejob (1881). Marc-Antoine Muret: un professeur français en Italie dans la seconde moitié du XVIe siècle (in French). Paris: E. Thorin.

- ^ Paul Schmitt (1985). La Réforme catholique: le combat de Maldonat (1534-1583) (in French). Paris: Editions Beauchesne. pp. 350–359. ISBN 978-2-7010-1117-2.

- ^ Charles Nisard (1860). Les gladiateurs de la république des lettres (in French). Vol. Tome second. Paris: Michel Levy Frères. pp. 207–321.

- ^ Erwin Fahlbusch; Geoffrey William Bromiley (2008). The Encyclodedia of Christianity. Vol. Si–Z. Grand Rapids MI USA: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2.

- ^ Université de Poitiers, Secteurs d' activité

- ^ A church in Poitiers was named in honor of a S. Agon, from which came the assumption that he had been a bishop. He was honored in the Basilica of S. Hilarius on 24 August. Gallia christiana II, p. 1137, 1223. Cf. Duchesne, pp. 77, 82.

- ^ Lionel R. Wickham (1997). Hilary of Poitiers, Conflicts of Conscience and Law in the Fourth-century Church: "Against Valens and Ursacius", the Extant Fragments, Together with His "Letter to the Emperor Constantius". Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-572-9.

- ^ The five bracketed bishops occur in the 12th century list, but are otherwise undocumented. They are omitted by Duchesne.

- ^ Duchesne, p. 82 no. 2, points out that an Adelfius episcopus de Ratiate (Retz), who in another version of the subscription list is ex civitate Pectavos Adelfios episcopus, was present at the Council of Orléans in 511, and an Adelfius was represented at the Council of Orléans in 533 (though without mention of his See). C. De Clercq, Concilia Galliae, A. 511 – A. 695 (Turnhout: Brepols 1963), pp. 13 and 19; 103.

- ^ Bishop Daniel was present at the Council of Orléans in 541 (but not at the Council of Orléans in 538). Duchesne, p. 83 no. 4. De Clercq, pp. 143 and 146.

- ^ Martha Gail Jenks (1999). From Queen to Bishop: A Political Biography of Radegund of Poiters. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California, Berkeley. pp. 130, 139, 158.

- ^ Duchesne, p. 83 no. 6.

- ^ Maroveus is often spoken of by Gregory of Tours: Duchesne, p. 83 no. 7. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1145–1148. Raymond Van Dam (2011). Saints and Their Miracles in Late Antique Gaul. Princeton University Press. pp. 30–40. ISBN 978-1-4008-2114-3.

- ^ Plato had been Gregory of Tours' Archdeacon, and Gregory took part in his installation as Bishop of Poitiers: Duchesne, p. 83. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1148–1149.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, pp. 1149–1151. Duchesne, p. 83 no. 9. Judith George (1995). Venantius Fortunatus: Personal and Political Poems. Liverpool University Press. pp. xvii–xxiv. ISBN 978-0-85323-179-0.

- ^ Ennoaldus was present at the Council of Paris in 614. De Clercq, p. 281.

- ^ Joannes was present at the Council of Clichy in 627. De Clercq, p. 297.

- ^ Dido was the maternal uncle of Leodegarius (Léger), Bishop of Autun (who was brought up in Poitiers and became Archdeacon), and of Gerinus Count of Poitou. Duchesne, p. 84 no. 13. Jean-Michel Picard (1991). Ireland and Northern France, AD 600-850. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 27–28, 39. ISBN 978-1-85182-086-3.

- ^ Ansoald: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1153–1154. J. Tardif, "Les chartes mérovingiennes de Noirmoutier," Nouvelle revue historique de droit franc̜ais et étranger (in French). Vol. 22. Paris: L. Larose. 1898. pp. 763–790, at 768–783. Ulrich Nonn, "Zum 'Testament' Bischof Ansoalds von Poitiers," Archiv für Diplomatik (1972), 413-418 (in German). Paul Fouracre, "Merovingian History and Merovingian Hagiography." Past & Present, no. 127 (1990): 3-38, at 14-15; https://www.jstor.org/stable/650941.

- ^ Eparchius: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1154–1155. Duchesne, p. 85 no. 15.

- ^ Maximinus: Gallia christiana II, p. 1155.

- ^ Godo: Gallia christiana II, p. 1155.

- ^ Joannes: Duchesne, p. 85 no. 22.

- ^ Fridebertus: Gallia christiana II, p. 1156. Gams, p. 601 column 2.

- ^ Ebroin: He presided at the second Concilium Vernense in 844: J.D. Mansi (ed.), Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, editio novissima, Tomus XIV (Venice 1759), p. 809. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1156–1158. Duchesne, p. 86 no. 25.

- ^ Engenoldus, or Ingenaldus, or Ingenardus was present at the II Concilium Tullense (apud Tusiacum villam) in 860, and at the Assembly of the three Kings of the Franks in 862. J.-D. Mansi, ed. (1770). Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio (in Latin). Vol. Tomus XV (editio novissima ed.). Venice: A. Zatta. pp. 561, 633 and 636. Engenoldus also subscribed the synodal letter to Pope Hadrian I of the Concilium Duziacense in 871: Mansi (ed.), Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, editio novissima, Tomus XVI (Venice 1761), p. 678. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1158–1159.

- ^ Hecfridus received a confirmation of the privileges of the diocese of Poitiers from Pope John VIII on 30 August 878: Mansi (ed.), Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, editio novissima, Tomus XVII (Venice 1762), pp. 351–352. Gallia christiana II, p. 1159.

- ^ Froterius: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1159–1160. Gams, p. 602.

- ^ Petrus was former Archdeacon and Provost of S. Peter in Poitiers, appointed by Froterius II. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1160–1161.

- ^ Gislebert had previously been Archdeacon of Poitiers. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1161–1162.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 1162-1164. Bishop Isimbert is mentioned in a charter of Count Guillaume of Poitou dated 30 September 1028, in which it is stated that Isembert is in his fifth year as Bishop of Poitiers: M. de Bréquigny (Louis-Georges-Oudard Feudrix); Louis-Georges Oudart Feudrix de Bréquigny; Georges Jean Mouchet (1769). Table chronologique des diplomes, chartes, titres et actes imprimés, concernant l'histoire de France (in French and Latin). Vol. Tome premier. Paris: Imprimerie royale. p. 560.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 1164-1167.

- ^ Peter had previously been Archdeacon of Poitiers. He was exiled by William IX, Count of Poitiers, whose divorce he refused to sanction. Gallia christiana II, p. 1167-1170.

- ^ Guillaume was driven from his diocese because of the schism between Pope Anacletus II and Innocent II Etienne Richard (1859). Étude historique sur le schisme d'Anaclet en Aquitaine de 1130 à 1136 (in French). Poitiers: Henri Oudin. pp. 28–31.

- ^ Grimoard had been Abbot of Alleux before being elected by the Chapter of Poitiers. He was consecrated on 26 January 1141 by Archbishop Gaufridus de Loratorio of Bordeaux, though King Louis VII refused to allow him to occupy his seat, apparently because he was consecrated without having first obtained the royal sanction: Marcel Pacaut (1957). Louis VII et les élections épiscopales dans le royaume de France (in French). Vrin. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-2-7116-0592-7. On 20 May 1141, Pope Innocent II wrote to Bishop Grimoard, noting his recent accession and exhorting him to carry out his mission in praiseworthy fashion. J. P. Migne (ed.), Patrologiae Latinae cursus completus Tomus CLXXIX (Paris 1899), p. 547; P. Jaffé, Regesta pontificum Romanorum I, second edition (Leipzig 1885), p. 897 no. 8145. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1173–1175.

- ^ Gilbert died in the thirteenth year of his pontificate. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1175–1178. Gams, p. 602 column 1. Auguste Berthaud, Gilbert de la Porrée, évêque de Poitiers, et sa philosophie 1070-1154 (Poitiers, 1892). Nikolaus Martin Häring, "The Case of Gilbert de la Porrée, Bishop of Poitiers, 1142-1154," Medieval Studies 13 (1951), pp. 1–40. Nikolas Häring (1966). Gilbert of Poitiers: The Commentaries on Boethius. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. pp. 4–13. ISBN 978-0-88844-013-6.

- ^ Calo had been Archdeacon of Thouars in the Church of Poitiers. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1178–1179.

- ^ Laurentius had been Dean of the Cathedral Chapter of Poitiers by 1154. Gallia christiana II, p. 1179.

- ^ Guillaume Tempier had been a Canon Regular in the abbey of Saint Hilaire de Cella (Poitiers). Roger of Hoveden [William Stubbs (editor), Chronica Magistri Rogeri de Houedene Vol. IV (London 1871), p. 24] says of him that, although his life appeared to people to be really reprehensible, nevertheless after his death he shone forth with miracles. Gallia christiana II, p. 1181.

- ^ Ademar was elected after a six-month vacancy in a contested election. The matter was referred to the Pope, and Ademar set out for Rome, where Innocent III settled the matter and consecrated him personally. See the letter of Innocent III of April 6, 1198. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1181–1182. A. Potthast, Regesta pontificum Romanorum I (Berlin 1874), p. 9 nos. 73-74.

- ^ Blaron: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1182–1183. Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Guillaume Prévost: He died after 3 April 1224 and before 18 November 1224, when his successor Philippe Balleos is already installed. The necrology of the Dominicans of Poitiers put the date on 3 August. Louis de la Boutetière, "Note sur Guillaume Prévost, évêque de Poitiers (1214–1224)," Bulletins de la Société des antiquaires de l'Ouest. XIII serie (in French). Paris: Derache. 1874. pp. 56–59.

- ^ Balleos: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1183–1184. Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Jean de Melun: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1184–1185. Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Châteauroux: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1185–1186. Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Gualterus de Bruges had been Provincial of the French Province of the Franciscans before his appointment to Poitiers. He resigned in 1306, on or before 4 November, and died on 21 January 1307. Jean-François Dreux-Duladier (1842). Bibliothèque historique et critique du Poitou (in French). Vol. Tome I. Niort: Robin. pp. 53–56. Ephrem Longpre, O.F.M., Quaestiones disputatae du B. Gauthier de Bruges (Louvain, 1928), pp. i–iii (in French). Andre Callebaut, O.F.M., "Les provincaux de la province de France," Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 10 (1917), pp. 337–340. Benoît Patar (2006). Dictionnaire des philosophes médiévaux (in French). Longueuil Quebec: Les Editions Fides. p. 145. ISBN 978-2-7621-2741-6.

- ^ Arnaud d'Aux was a Gascon, of La Romieu or Larromieu, in the diocese of Cahors, and a cousin of Pope Clement V. He was Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Church (1312–1319). He was named a cardinal by Pope Clement on 23 or 24 December 1312, and transferred to the suburbicarian diocese of Albano. While still Bishop of Poitiers he had been sent to England as a papal legate on 14 May 1312 to King Edward II after the murder of Piers Gaveston; he was still there in November 1313. He died on 14 August 1320. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1188–1190. Eubel, I, pp. 14 no. 17; 399.

- ^ Fortius was the nephew of Cardinal Arnaud d'Aux, by whom he was consecrated a bishop on 17 October 1316. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1190–1191. Eubel, I, p. 399 with note 5.

- ^ Jean de Lieux: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1191–1192. Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Aimery de Mons, a native of the diocese of Poitiers, was a Doctor in utroque iure (Civil and Canon Law). 4 June 1363 is the date of his solemn entry into Poitiers. His tombstone says he died on 17 March 1370. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1191–1192. Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Born at Malsec in the diocese of Tulle, Guy de Malsec was the nephew of Pope Gregory XI. He obtained a degree of Doctor of Canon Law, which led to a position as a papal Referendary (judge). He was Cantor in the Cathedral Chapter of Langres in 1351, and Archdeacon of Corbaria in the Church of Narbonne. He became Bishop of Lodève for a short time (1370–1371) before being promoted to the See of Poitiers. He was named a cardinal on 20 December 1375, and appointed suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina in 1383. He was a leading figure in the Council of Pisa (1409) and the election of Pope Alexander V. From 1409 to 1411 he was Administrator of the diocese of Agde. He died in Paris on 8 March 1412. Charles François Roussel (1879). La diocèse de Langres: histoire et statistique (in French). Vol. Tome IV. Langres: J. Dallet. p. 83. Eubel, I, pp. 22 no. 17; 76 with note 9; 310; 399.

- ^ A native of the diocese of Limoges, Bertrand de Maumont (not de Cosnac; Maumont is a village in Haute-Vienne) had previously been Bishop of Tulle (1371–1376). He consecrated the cathedral in Poitiers on 17 October 1379. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1194–1196. Auber, II, pp. 120–130. Eubel, I, p. 399, 505.

- ^ Simon de Cramaud had previously been Bishop of Agen (1382-1383), and then Bishop of Béziers (1383–1385). He was named Patriarch of Alexandria on 17 March 1391. He was named Archbishop of Reims on 2 July 1409. He was named a cardinal on 13 April 1413 by Pope John XXIII. He died on 15 December 1422. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1194–1196. Eubel, I, pp. 33, 77, 82, 138, 399, 419. Howard Kaminsky, "The Early Career of Simon De Cramaud," Speculum 49, no. 3, 1974, pp. 499–534, www.jstor.org/stable/2851753. Bernard Guenée (1991). Between Church and State: The Lives of Four French Prelates in the Late Middle Ages. University of Chicago Press. pp. 154–155, 175–179, 205–211, 223–224, 251. ISBN 978-0-226-31032-9.

- ^ Louis de Bar was the son of Robert, Duc de Bar, and Marie, the daughter of King John of France. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1196–1197. Eubel, I, p. 399. D. De Smyttère, "Enfants du duc de Bar Robert et de la princesse Marie," in: Mémoires de la Société des lettres, sciences et arts de Bar-le-Duc. deuxième série (in French). Vol. Tome III. Bar-le-Duc: L. Philipona. 1884. pp. 307–326.

- ^ A Doctor of Canon Law, Ythier de Mareuil had previously been Cantor in the Cathedral Chapter of Poitiers, and then Bishop of Le Puy (Aniciensis) (1382–1395). Gallia christiana II, pp. 720, 1197. Eubel, I, pp. 91, 399.

- ^ Bishop Gérard de Montaigu, the brother of Jean, Archbishop of Sens, had been Chancellor of Jean, Duc de Berry. He was appointed Bishop of Poitiers by Pope Benedict XIII. He was transferred from Poitiers to the diocese of Paris on 24 July 1409 by Pope Alexander V. He died on 25 September 1420. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1197–1198. Eubel, I, pp. 391, 399.

- ^ Pierre Trousseau had been Archdeacon of Paris. He was transferred from Poitiers to Reims on 2 May 1413, and died on 16 December 1413. Gallia christiana II, p. 1198. Eubel, I, p. 399, 419.

- ^ Louis de Bar: Eubel, I, p. 399.

- ^ Hugh de Combarel had been Bishop of Tulle (1419–1422) and Bishop of Béziers (1422–1424). Gallia christiana II, pp. 1198–1199. Eubel, I, pp. 138, 399, 505.

- ^ Guillaume Gouge was the Chancellor of Jean, Duke of Burgundy. He was elected by the Dean and Chapter of Poitiers, and confirmed on 17 May 1441 by Archbishop Henri d'Avaugour of Bourges. His bulls were passed on 15 December 1441. Gallia christiana II, p. 1199. Eubel, II, p. 216.

- ^ Jacques Juvénal des Ursins had been Archbishop of Reims (1444–1449). On 3 March 1449 he was named both titular Patriarch of Antioch and Bishop of Poitiers. Michiel Decaluwe; Thomas M. Izbicki; Gerald Christianson (2016). A Companion to the Council of Basel. Leiden-Boston: Brill. pp. 389, 409. ISBN 978-90-04-33146-4. Roger Aubert, "Jouvenel des Ursins (Jacques)," Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques 28 (2003), p. 370. Eubel, II, pp. 216, 222.

- ^ Gallia christiana II, p. 1200. Eubel, II, pp. 155 with note 3; 216.

- ^ Jean du Bellay had been Bishop of Frejus (1455–1462). Gallia christiana II, p. 1201. Eubel, II, pp. 155, 216.

- ^ Guillaume was a Protonotary Apostolic and Bishop-Elect of Évreux. Gallia christiana II, p. 1201-1202. Eubel, II, pp. 148 with note 5; 216.

- ^ Pierre d'Amboise was the brother of Cardinal Georges d'Amboise. Gallia christiana II, p. 1202. Eubel, II, p. 216 with note 3; III, p. 273 with note 2. Francois Villard, "Pierre d'Amboise, évêque de Poitiers (1481–1505)," Mélanges René Crozet Tome II (Poitiers 1966), pp. 1381–1387.

- ^ La Trémoïlle: Eubel, III, p. 273.

- ^ Claude de Husson had been Bishop of Séez (1503–15 He was appointed to Poitiers on 10 September 1507, but faced opposition from another candidate (who died in 1510). Gallia christiana II, p. 1203. Eubel, II, p. 227; III, p. 273 with note 4.

- ^ Husson was the nephew of Bishop Claude de Husson, and was appointed to succeed his uncle at the age of 18. He was never consecrated a bishop, and applied to the Pope in 1532 for a dispensation to marry. He resigned his See. Peter G. Bietenholz; Thomas Brian Deutscher (2003). Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation. Vol. II. University of Toronto Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-8020-8577-1.

- ^ Gramont had been French Ambassador to the Pope. He had been Archbishop of Bordeaux (1529–1530. He was named a cardinal by Pope Clement VII on 8 June 1530. Gallia christiana II, pp. 1203–1204. Eubel, III, pp. 21, 273–274.

- ^ Longwy was Bishop of Langres (1528– ) He made his solemn entry into Poitiers in 1541. He died on 9 August 1561. Gallia christiana II, p. 1204. Eubel, III, pp. 22 no. 31; 274.

- ^ Jean d'Amoncourt was a Doctor in utroque iure (Civil and Canon Law). Gallia christiana II, p. 1204. Eubel, III, p. 274.

- ^ Peyrusse was transferred to the diocese of Langres on 19 December 1569. Gallia christiana II, p. 1204. Eubel, III, p. 226, 274.

- ^ Du Fay: Gallia christiana II, p. 1205. Gams, p. 602 column 2. Eubel, III, p. 274.

- ^ Saint-Belin: Gallia christiana II, p. 1205. Jean-Francois Dreux du Radier (1746). Bibliothéque Historique, Et Critique Du Poitou (in French). Vol. Tome premier. Paris: Ganeau. pp. 52–53. Gams, p. 603 column 1. Eubel, III, p. 274. Favreau and Pon, p. 114, 130-138.

- ^ Roche-Posay: Gallia christiana II, pp. 1206–1207. Gauchat, IV, p. 280. Marcelle Formon, "Henri-Louis Chasteigner de la Rocheposay, évêque de Poitiers (1612–51)," Bulletin de la Société des Antiquaires de l'Ouest 4th series, 3 (1955), pp. 169–231.

- ^ Barberini, a nephew of Pope Urban VIII, who was in exile from Rome after his uncle's death, having broken publicly from the new Pope Innocent X, was appointed Bishop of Poitiers by King Louis XIV, but he was unable to obtain his bulls of institution. He was therefore only civil administrator. He participated in the Conclave of 1655 as Cardinal Camerlengo S.R.E., which elected Pope Alexander VII. He was named suburbicarian Bishop of Frascati on 11 October 1655, and on 24 October 1655 he was finally consecrated a bishop by his uncle, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, the elder. He died on 3/4 August 1671. Gallia christiana II, p. 1208.

- ^ Clérembault was a Doctor in utroque iure (Civil and Canon Law). He was nominated by King Louis XIV on 1 September 1657, and approved (preconised) by Pope Alexander VII on 1 April 1658. Gauchat, IV, p. 280 with note 3.

- ^ Fortin de La Hoguette was transferred to the diocese of Sens on 21 January 1692. He died on 28 November 1715. Jean, pp. 142–143. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, pp. 314 with note 3; 354 with note 4.

- ^ Baglion de Saillant had previously been Bishop of Tréguier (1679–1692). He was nominated to the diocese of Poitiers by King Louis XIV on 26 April 1686, but did not receive his bulls from Pope Innocent XI due to a break in relations between the Papacy and France and the excommunication of Louis XIV. Jean, p. 144. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, pp. 314 with note 4; 387 with note 3.

- ^ Girard was born in Clermont, and held a doctorate in theology (Paris); he was a fellow of the Sorbonne. Jean, pp. 144–145. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 314 with note 5.

- ^ Born in 1654, La Poype de Vertrieu was Comte de Lyon. Jean, p. 144. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 314 with note 6.

- ^ Courcenay was a nephew or coursin of Bishop La Poype de Vertrieu. He was named his Coadjutor and titular Bishop of Tlos, from 8 January 1721. Jean, pp. 144–145. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 314 with note 7; 382.

- ^ Caussade was a native of Périgueux, and held a doctorate in theology (Paris). For six years he was Theological Canon and Vicar General of Tarbes. He resigned the diocese of Poitiers on 12 March 1759, and was appointed Bishop of Meaux on 9 April 1759. He died on 19 February 1769. Jean, p. 145. Ritzler-Sefrin, VI, pp. 284 with note 3; 337 with note 2.

- ^ Beaupoil was born in the diocese of Limoges, and held a Licenciate in theology (Paris). He served as Vicar General of Rouen for nine years. He died in exile in Freibourg im Breisgau in 1798. Jean, p. 145. Ritzler-Sefrin, VI, p. 337 with note 3.

- ^ Bailly: Béduchaud, p. ix.

- ^ De Pradt: Béduchaud, p. ix.

- ^ De Bouillé: Béduchaud, p. ix. A. C. (1842). Notice sur Mgr Jean-Baptiste de Bouillé, évêque de Poitiers. Journal de la Vienne, 26 April 1842 (in French). Poitiers: imprimerie de F.-A. Saurin.

- ^ Guitton: Béduchaud, p. x.

- ^ Pie: Béduchaud, p. x.

- ^ Bellot des Minières was born in Poitiers in 1822. Béduchaud, p. x. Livio Rota (1996). Le nomine vescovili e cardinalizie in Francia alla fine del sec. XIX (in Italian). Rome: Gregorian University. pp. 151–159. ISBN 978-88-7652-690-9.

- ^ Juteau: Béduchaud, p. x. Rota, pp. 151–199.

- ^ Pelgé: Béduchaud, p. x.

- ^ Humbrecht was born in Gueberschwir (Haut-Rhin) in 1853. He had been Vicar General in Besançon. On 14 September 1918 he was transferred to the diocese of Besançon. He died in 1927. Almanach catholique français pour 1920 (in French). Paris: Bloud et Gay. 1920. p. 74. The Catholic Encyclopedia: Supplement I. New York: Encyclopedia Press. 1922. p. 105.

- ^ Durfort, a native of the diocese of Le Mans, studied at the French seminary in Rome. He was a priest of Mans, and an honorary Canon of Rennes. He was previously Bishop of Langres (1911–1918).

- ^ Archbishop Pascal Jean Marcel Wintzer.

- ^ Wintzer was born in Rouen in 1956. He holds the degree of Master in dogmatic theology. He was named Auxiliary Bishop of Poitiers on 2 April 2007, and consecrated on 19 May. He became Administrator of the diocese on 2 February 2011, and was named Archbishop of Poitiers on 13 January 2012. Catholiques en Poitou: Site officiel du diocèse de Poitiers, Mgr Pascal Wintzer, retrieved: 2017-05-05.(in French)

Bibliography

[edit]Reference works

[edit]- Gams, Pius Bonifatius (1873). Series episcoporum Ecclesiae catholicae: quotquot innotuerunt a beato Petro apostolo. Ratisbon: Typis et Sumptibus Georgii Josephi Manz. (Use with caution; obsolete)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1913). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 1 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. (in Latin)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1914). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 2 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. (in Latin)

- Eubel, Conradus (ed.); Gulik, Guilelmus (1923). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 3 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Gauchat, Patritius (Patrice) (1935). Hierarchia catholica IV (1592-1667). Münster: Libraria Regensbergiana. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1952). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi V (1667-1730). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1958). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi VI (1730-1799). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1968). Hierarchia Catholica medii et recentioris aevi sive summorum pontificum, S. R. E. cardinalium, ecclesiarum antistitum series... A pontificatu Pii PP. VII (1800) usque ad pontificatum Gregorii PP. XVI (1846) (in Latin). Vol. VII. Monasterii: Libr. Regensburgiana.

- Remigius Ritzler; Pirminus Sefrin (1978). Hierarchia catholica Medii et recentioris aevi... A Pontificatu PII PP. IX (1846) usque ad Pontificatum Leonis PP. XIII (1903) (in Latin). Vol. VIII. Il Messaggero di S. Antonio.

- Pięta, Zenon (2002). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentioris aevi... A pontificatu Pii PP. X (1903) usque ad pontificatum Benedictii PP. XV (1922) (in Latin). Vol. IX. Padua: Messagero di San Antonio. ISBN 978-88-250-1000-8.

Studies

[edit]- Jean, Armand (1891). Les évêques et les archevêques de France depuis 1682 jusqu'à 1801 (in French). Paris: A. Picard.

- Auber, Charles Auguste (1849). Histoire de la cathédrale de Poitiers (in French). Vol. Tome I. Poitiers: Derache.

- Auber, Charles Auguste (1849). Histoire de la Cathédrale de Poitiers (in French). Vol. Tome II. Poitiers: Derache.

- Baunard, Louis (Mgr.) (1886). Histoire du Cardinal Pie, Évêque de Poitiers (in French). Vol. II (deuxième ed.). Poitiers: H. Oudin.

- Beauchet-Filleau, Henri (1868). Pouillé du diocèse de Poitiers (in French). Niort: L. Clouzot.

- Béduchaud, J. M. U. (1906). Le clergé du diocèse de Poitiers depuis le Concordat de 1801 jusqu'à nos jours: les évêques et les prêtres morts depuis le Concordat jusqu'au 31 décembre 1905 (in French). Poitiers: Société française d'imprimerie et de librairie.

- Delfour, Joseph (1902). Les jésuites à Poitiers (1604-1762) (in French). Paris: Hachette & Cie.

- Duchesne, Louis (1910). Fastes épiscopaux de l'ancienne Gaule: II. L'Aquitaine et les Lyonaises. Paris: Fontemoing. second edition (in French)

- Favreau, Robert; Pon, Georges (1988). Le Diocèse de Poitiers (in French). Poitiers: Editions Beauchesne. ISBN 978-2-7010-1170-7. [A list of bishops at pp. 341–342]

- Foucart, Émile-Victor (1841). Poitiers et ses monuments (in French). Poitiers: A. Pichot.

- Fournier, Marcel; Charles Engel (1892). Les statuts et privilèges des universités françaises depuis leur fondation jusqu'en 1789: ouvrage publié sous les auspices du Ministère de l'instruction publique et du Conseil général des facultés de Caen. Paris: L. Larose et Forcel. pp. 283–336.

- Galtier, Paul, SJ (1960). Saint Hilaire de Poitiers, Le premier Docteur de l'eglise latine (in French). Paris: Editions Beauchesne. GGKEY:PZZ3WGK4Q1G.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haring, Nicholas M. (1951). The Case of Gilbert de la Porrée, Bishop of Poitiers, 1142-1154.

- Kaminsky, Howard (1983). Simon De Cramaud and the Great Schism. New Brunswick, N.J. USA: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-0949-5.

- Rennie, Kriston R. (2007), "The Council of Poitiers (1078) and Some Legal Considerations," Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law, Vol. 27 (n.s. 1) pp. 1–20.

- Sainte-Marthe, Denis de (1720). Gallia Christiana: In Provincias Ecclesiasticas Distributa... Provinciae Burdigalensis, Bituricensis (in Latin). Vol. Tomus secundus. Paris: Typographia Regia. pp. 1136–1363.

- Tableau des évêques constitutionnels de France, de 1791 a 1801 (in French). Paris: chez Méquignon-Havard. 1827. p. 32.

- Vallière, Laurent (ed.) (2008): Fasti Ecclesiae Gallicanae. Répertoire prosopographique des évêques, dignitaires et chanoines des diocèses de France de 1200 à 1500. X. Diocèse de Poitiers. Turnhout, Brepols. (in French) [A convenient summary list of the bishops is given at p. 429.]

External links

[edit]- (in French) Centre national des Archives de l'Église de France, L’Épiscopat francais depuis 1919, retrieved: 2016-12-24.