Arambourgiania

| Arambourgiania Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype fossil cast at Museum Histoire Naturelle, Paris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Azhdarchidae |

| Subfamily: | †Quetzalcoatlinae |

| Genus: | †Arambourgiania Nessov vide Nessov & Yarkov, 1989 |

| Species: | †A. philadelphiae

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Arambourg, 1959)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

Arambourgiania is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur that lived during the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous, in what is now Jordan. Additional fossil remains from the United States and Morocco have also been found, but their assignment to Arambourgiania is only tentative. The original specimen was discovered in the 1940s by a railway worker near Russeifa, Jordan. After examination by paleontologist Camille Arambourg, a new species was named in 1959, Titanopteryx philadelphiae. The generic name means "titan wing", as the fossil was initially misidentified as a huge wing metacarpal (it would be later identified as a cervical (neck) vertebra), while the specific name refers to the ancient name of Amman (the capital of Jordan), Philadelphia. The genus "Titanopteryx" would later be problematic, as it had already been taken by a fly. Because of this, paleontologist Lev Nessov in 1989 named a new genus, Arambourgiania, in honor of Arambourg. The new species was now known as Arambourgiania philadelphiae.

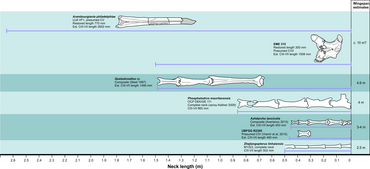

Arambourgiania is one of the largest flying animals ever discovered. Initial wingspan estimates ranged from 11 to 13 m (36 to 43 ft), which would have made it the largest known pterosaur. However, due to Arambourgiania only presenting fragmentary specimens, recent research has suggested more moderate wingspan estimates. Some of the latest studies put the wingspan anywhere between 8 to 10 m (26 to 33 ft), which would still be among the largest known flying creatures. Arambourgiania has often been compared to other gigantic pterosaurs such as Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx in terms of size.

Arambourgiania is a member of the family Azhdarchidae, which includes some of the largest known pterosaurs ever. One of the closest relatives of Arambourgiania is Quetzalcoatlus, as multiple studies have found both pterosaurs to be grouped together within Azhdarchidae.

History of discovery

[edit]

In the early 1940s, a railway worker during repairs on the Amman-Damascus railroad, near the city of Russeifa in Jordan, found a fossil bone measuring 60.96 cm (2 ft). This specimen was acquired in 1943 by the director of a nearby phosphate mine, Amin Kawar, who brought it to the attention of British archeologist Fielding after the Second World War. This generated some publicity — the bone was even shown to Abdullah I of Jordan — but more importantly, it made the scientific community aware of the find.[1]

In 1953, the fossil was sent to the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France, where it was examined by French paleontologist Camille Arambourg. In 1954, he concluded the bone was the wing metacarpal of a giant pterosaur. Afterwards, in 1959, he named a new genus and species: Titanopteryx philadelphiae. The generic name meaning "titan wing" in Greek, referring to the enormous size of the fossil, while the specific name refers to the ancient name of Amman that was used by the Greeks: Philadelphia. Arambourg let a plaster cast be made and then sent the fossil back to the phosphate mine; this last aspect was later forgotten and the bone was assumed lost.[1]

While studying and describing the closely related pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus from Texas in 1975, American paleontologist Douglas A. Lawson concluded that the bone was not a metacarpal but a cervical (neck) vertebra.[2]

In the 1980s, Russian paleontologist Lev Nesov was informed by an entomologist that the name Titanopteryx had already been given by Günther Enderlein to a fly from the Simuliidae family in 1935. Therefore, in 1989, he renamed the genus into Arambourgiania, honoring Arambourg.[3] However, the name "Titanopteryx" was informally kept in use in the West, partially because the new name Arambourgiania was assumed by many to be a nomen dubium (dubious name).[4]

In early 1995, paleontologists David Martill and Eberhard Frey traveled to Jordan in an attempt to clarify matters. In a cupboard of the office of the Jordan Phosphate Mines Company they discovered some other pterosaur bones: a smaller vertebra and the proximal and distal extremities of a wing phalanx — but not the original material of Arambourgiania. However, after their departure to Europe, engineer of the mine Rashdie Sadaqah investigated further and in 1996 he established that the original fossil had been bought from the company in 1969 by geologist Hani N. Khoury, who had then donated it in 1973 to the University of Jordan. It was still present in the collection of this institute and now it could be restudied by Martill and Frey.[5][6][4]

Later, Frey and Martill rejected the suggestion that Arambourgiania was a nomen dubium or an identical pterosaur to Quetzalcoatlus, affirming its validity to replace the preoccupied name "Titanopteryx".[5][4]

In 2016, an azhdarchid cervical vertebra (MPPM 2000.23.1) was described from the Coon Creek Formation of McNairy County in Tennessee, United States. It was referred to A. philadelphiae, which may potentially extend the geographic range of Arambourgiania to North America.[7] However, this specimen was later referred to as cf. Arambourgiania, indicating a species of uncertain affinities.[8] In 2022, American paleontologist Gregory S. Paul stated that it may not even belong to Arambourgiania itself.[9]

In 2018, topotype specimens were located in Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology in Munich, Germany that were placed there in 1966 from Jordan. These probably represent additional elements of the holotype individual. They are identified as cf. Arambourgiania and include the fragments of two cervical vertebrae, a neural arch, a left femur, a possible radius, and a metacarpal IV, as well as other indeterminate fragments.[10] The incomplete left ulna of the "Sidi Chennane azhdarchid" from Morocco has also been identified as cf. Arambourgiania.[11]

In 2024, the describers of the genus Inabtanin discovered a large partial right humerus of a large pterosaur in the Ruseifa Phosphate Mines, near the Jordanian capital of Amman, which was where the holotype of Arambourgiania was recovered. They concluded that the specimen belonged to A. philadelphiae and that it is comparable in size and shape to the humerus of the type species of Quetzalcoatlus, Q. northropi.[12]

Description

[edit]

The holotype of Arambourgiania, UJA VF1, consists of a very elongated cervical vertebra, probably the fifth. Today the middle section is missing; the original material was about 62 cm (2 ft 0.41 in) long, but had been sawed into three parts. Most of the fossil now consists of an internal infilling or mold; the thin bone walls are missing on most of the surface. The holotype does not present the whole vertebra; a piece is absent from its posterior end as well.[4]

Frey and Martill estimated the total length of the holotype to have been 78 cm (2 ft 7 in), using for comparison the relative position of the smallest diameter of the shaft of the fifth cervical vertebra of Quetzalcoatlus. The total neck length was extrapolated at about 3 m (9 ft 10 in) using the same method. From the relatively slender vertebra, the length dimension was then selected to be compared to that of Quetzalcoatlus as well, estimated at 66 cm (2 ft 2 in) long, which results in a ratio of 1.18. Applying that ratio to the overall size, Frey and Martill in the late 1990s concluded that the wingspan of Arambourgiania was 11 to 13 m (36 to 43 ft), larger than the estimated wingspan of Quetzalcoatlus, which measured 10 to 11 m (33 to 36 ft). This would have made Arambourgiania the largest pterosaur ever known.[5][4] In 1997, paleontologist Lorna Steel and colleagues reconstructed a life-sized skeleton of Arambourgiania based on better-known related pterosaurs. They set its wingspan at 11.5 m (38 ft), within the range of Frey and Martill's estimate.[6]

Subsequently, the estimates proposed by Frey and Martill in the late 1990s were taken into question, with later estimates of the wingspan of Arambourgiania being more moderate. This was due to the remains being too fragmentary to estimate a gigantic size. In 2003, the researchers who described the related pterosaur Phosphatodraco stated that the wingspan of Arambourgiania was more likely at 7 m (23 ft), though this measurement was not given a rationale.[13] In 2010, paleontologists Mark Witton and Michael Habib argued that a 7 m (23 ft) wingspan is an underestimate for Arambourgiania, while a 11 to 13 m (36 to 43 ft) wingspan would be too much.[14]

In his 2022 pterosaur book, Paul proposed that Arambourgiania had a wingspan of 8 to 9 m (26 to 30 ft), making it smaller than that of Quetzalcoatlus northropi, which he kept at 10 to 11 m (33 to 36 ft). Arambourgiania would have also had a smaller wingspan than that of the related Hatzegopteryx from Romania, which Paul situated at 10 to 12 m (33 to 39 ft). Just like both Arambourgiania and Quetzalcoatlus, Hatzegopteryx is also among the largest known flying animals to ever exist.[9] In a 2024 study, the wingspan of Arambourgiania was estimated to be around 10 m (33 ft) based on a large humerus comparable in size to that of Q. northropi. This new estimate for the wingspan of Arambourgiania is slightly larger than Paul's 2022 estimate, but does not surpass the wingspan of Quetzalcoatlus.[12]

Classification

[edit]

Arambourgiania was initially assigned to a newly named subfamily called Azhdarchinae by Nesov in 1984. It was still known as "Titanopteryx" at the time of the assignment. Azhdarchinae also included the pterosaurs Azhdarcho and Quetzalcoatlus. Nesov assigned the subfamily as part of the family Pteranodontidae, based on its members featuring toothless beaks just like the pteranodontids.[15] Unaware of the creation of Azhdarchinae, American paleontologist Kevin Padian created the family Titanopterygiidae, which included both "Titanopteryx" and Quetzalcoatlus. This new family was created on the basis of cervical form and proportions, and it was differentiated from Pteranodontidae, which also received a diagnosis by Padian the same year.[16][17] Two years later, in 1986, Padian would become aware of the existence of Azhdarchinae and would make Titanopterygiidae a junior synonym of it, as he believed that the diagnoses of the cervical vertebrae for both groups were identical. He removed Azhdarchinae from Pteranodontidae based on his previous diagnoses, and he would further elevate it to family level, creating Azhdarchidae as it is known today.[18][17]

The placement of Arambourgiania within the family Azhdarchidae has been consistent in various studies, which is in a derived (advanced) position in the subfamily Quetzalcoatlinae. However, its specific location within the group has been somewhat disputed. One of the closest relatives of Arambourgiania is Quetzalcoatlus, as both pterosaurs have consistently been found together in multiple phylogenetic analyses, either as sister taxa or close to each other.[19][11][17][20] However, there have also been several studies opposing this placement and have instead favored a closer relationship between Arambourgiania and the azhdarchids Mistralazhdarcho and Aerotitan.[21][22][23]

Below are two cladograms showing different studies regarding the position of Arambourgiania within Azhdarchidae. The first one is based on the phylogenetic analysis by American paleontologist Brian Andres in 2021, which places Arambourgiania within Quetzalcoatlinae as the sister taxon to both species of Quetzalcoatlus, Q. northropi and Q. lawsoni.[17] The second cladogram is based on the 2023 study by paleontologist Rodrigo Pêgas and colleagues, in which they placed Arambourgiania in a trichotomy with Mistralazhdarcho and Aerotitan within Quetzalcoatlinae, contrasting its placement as the sister taxon of Quetzalcoatlus.[23]

|

Topology 1: Andres (2021). |

Topology 2: Pêgas and colleagues (2023).

|

Paleobiology

[edit]A 2024 study by paleontologist Kierstin Rosenbach and colleagues included the description of the humerus of Arambourgiania. They compared it to that of soaring birds and suggested that Arambourgiania itsef was also a soarer. This is in contrast to the contemporary pterosaur Inabtanin, which had a style of flight closer to those of continuously flapping birds.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Arambourg, C. (1959). "Titanopteryx philadelphiae nov. gen., nov. sp. Ptérosaurien géant". Notes Mém. Moyen-Orient. 7: 229–234.

- ^ Lawson, Douglas A. (1975). "Pterosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of West Texas: Discovery of the largest flying creature". Reports. Science. 187 (4180): 947–948. Bibcode:1975Sci...187..947L. doi:10.1126/science.187.4180.947. PMID 17745279. S2CID 46396417.

- ^ Nessov, L.A. (1989). "New Cretaceous-Paleogene birds of the USSR and some remarks on the origin and evolution of the class Aves". Trudy Zoologicheskogo Instituta AN SSSR (in Russian). 197: 78–97.

- ^ a b c d e Martill, D.M.; Frey, E.; Sadaqah, R.M.; Khoury, H.N. (1998). "Discovery of the holotype of the giant pterosaur Titanopteryx philadelphiae Arambourg, 1959, and the status of Arambourgiania and Quetzalcoatlus". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 207: 57–76. doi:10.1127/njgpa/207/1998/57.

- ^ a b c Frey, E.; Martill, D.M. (1996). "A reappraisal of Arambourgiania (Pterosauria, pterodactyloidea): one of the world's largest flying animals". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 199 (2): 221–247. doi:10.1127/njgpa/199/1996/221.

- ^ a b Steel, L.; Martill, D.M.; Kirk, J.; Anders, A.; Loveridge, R.F.; Frey, E.; Martin, J.G. (1997). "Arambourgiania philadelphiae: giant wings in small halls". The Geological Curator. 6 (8): 305–313. doi:10.55468/GC539.

- ^ Harrell, T. Lynn Jr.; Gibson, Michael A.; Langston, Wann Jr. (2016). "A cervical vertebra of Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from the Late Campanian micaceous facies of the Coon Creek Formation in McNairy County, Tennessee, USA". Bullettin Alabama Museum of Natural History. 33 (2): 94–103. ISSN 0196-1039.

- ^ Andres, B.; Langston, W. Jr. (2021). "Morphology and taxonomy of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (sup1): 142. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41S..46A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1907587. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 245125409.

- ^ a b Paul, Gregory S. (2022). The Princeton Field Guide to Pterosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 161. doi:10.1515/9780691232218. ISBN 9780691232218. S2CID 249332375.

- ^ Martill, David M.; Moser, Markus (2018). "Topotype specimens probably attributable to the giant azhdarchid pterosaur Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Arambourg 1959)". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455 (1): 159–169. Bibcode:2018GSLSP.455..159M. doi:10.1144/SP455.6. ISSN 0305-8719. S2CID 132649124.

- ^ a b Longrich, Nicholas R.; Martill, David M.; Andres, Brian; Penny, David (2018). "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". PLOS Biology. 16 (3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663. PMC 5849296. PMID 29534059.

- ^ a b c Rosenbach, K. L.; Goodvin, D. M.; Albshysh, M. G.; Azzam, H. A.; Smadi, A. A.; Mustafa, H. A.; Zalmout, I. S. A.; Wilson Mantilla, J. A. (2024). "New pterosaur remains from the Late Cretaceous of Afro-Arabia provide insight into flight capacity of large pterosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 44 (1). e2385068. Bibcode:2024JVPal..44E5068R. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2385068.

- ^ Suberbiola, Xabier Pereda; Bardet, Nathalie; Jouve, Stéphane; Iarochène, Mohamed; Bouya, Baâdi; Amaghzaz, Mbarek (2003). "A new azhdarchid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 79–90. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217...79S. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.08. S2CID 135043714.

- ^ Witton, M.; Habib, M.B. (2010). Laudet, V. (ed.). "On the Size and Flight Diversity of Giant Pterosaurs, the Use of Birds as Pterosaur Analogues and Comments on Pterosaur Flightlessness". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e13982. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513982W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013982. PMC 2981443. PMID 21085624.

- ^ Nesov, L. A. (1984). "Upper Cretaceous pterosaurs and birds from Central Asia". Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal. 1984 (1): 47–57. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009.

- ^ Padian, Kevin (1984). "A large pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Two Medicine Formation (Campanian) of Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 4 (4): 516–524. Bibcode:1984JVPal...4..516P. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10012027. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ a b c d Andres, Brian (December 7, 2021). "Phylogenetic systematics of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (sup1): 203–217. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41S.203A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1801703. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 245078533.

- ^ Padian, Kevin (September 2, 1986). "A taxonomic note on two pterodactyloid families". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 6 (3): 289. Bibcode:1986JVPal...6..289P. doi:10.1080/02724634.1986.10011624. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303. S2CID 84617119.

- ^ Zhou, Xuanyu; Ikegami, Naoki; Pêgas, Rodrigo V.; Yoshinaga, Toru; Sato, Takahiro; Mukunoki, Toshifumi; Otani, Jun; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu (November 16, 2024). "Reassessment of an azhdarchid pterosaur specimen from the Mifune Group, Upper Cretaceous of Japan". Cretaceous Research. 167: 106046. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.106046. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Pêgas, R.V.; Holgado, B.; Ortiz David, L.D.; Baiano, M.A.; Costa, F.R. (August 21, 2021). "On the pterosaur Aerotitan sudamericanus (Neuquén Basin, Upper Cretaceous of Argentina), with comments on azhdarchoid phylogeny and jaw anatomy". Cretaceous Research. 129: Article 104998. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104998. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 238725853.

- ^ Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; González Riga, Bernardo J.; Kellner, Alexander W. A. (April 12, 2022). "Thanatosdrakon amaru, gen. ET SP. NOV., a giant azhdarchid pterosaur from the upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 135: 105228. Bibcode:2022CrRes.13705228O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105228. S2CID 248140163. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Pêgas, R. V.; Zhoi, X.; Jin, X.; Wang, K.; Ma, W. (2023). "A taxonomic revision of the Sinopterus complex (Pterosauria, Tapejaridae) from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota, with the new genus Huaxiadraco". PeerJ. 11. e14829. doi:10.7717/peerj.14829. PMC 9922500. PMID 36788812.