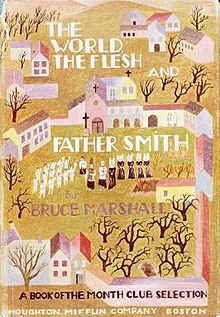

The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith

| |

| Author | Bruce Marshall |

|---|---|

| Genre | Novel |

Publication date | 1945 |

| Publication place | Scotland |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 191 |

| Preceded by | Yellow Tapers for Paris (1943) |

| Followed by | George Brown's Schooldays (1946) |

The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith (also known as All Glorious Within) is a 1944 novel by Scottish writer Bruce Marshall. The book was a June 1945 Book of the Month Club selection and was also produced as an Armed Services Edition.[1]

Plot summary

[edit]This is the fictional life story of a parish priest, a man of God "conscious of the indwelling of the Trinity," living the life of grace in a drab industrial town, bringing the grace of God to weak human beings seduced by the devil’s ancient lures of the world and the flesh.

It covers the activities of Father Thomas Edmund Smith in his urban Scottish parish from 1908 until his death in 1942. On this framework, the author hangs the glowing tapestry of Father Smith's spiritual life, a life of sanctity, humility, and burning love of God. He interacts with a wide range of people, children, adults and other clerics. It also tracks the lives of two particular youths from their innocent childhood affections to their respectives lives as a priest and an actress.

From the dust jacket: "This is the story of Father Smith, priest in a Scottish city – of his friends, the exiled French nuns, of the Bishop, of Monsignor O'Duffy who wages simple, violent war against simple sins, of Father Bonnyboat, the liturgical scholar, of all the people who come into the gentle orbit of Father Smith – from Lady Ippecacuanha, that tweedy convert, to the slut Annie who drives her husband to murder."[2]

A major aspect of the book is the situation of the Catholic Church in Scotland - a minority Church in a predominantly Presbyterian country, which had emerged from centuries of religious persecution and is still the target of prejudice and religious discrimination throughout significant parts of the Scottish society. It is to a considerable degree the Church of recent immigrants, mainly Irish and Italians (with an additional influx of Polish refugees during World War II, in the later part of the book). Above all, it is predominantly a poor people's Church and is itself both poor and run on a shoestring. The book begins with Father Smith going a great distance on his bicycle, commuting between two far-flung locations where he has to officiate at Mass; a few chapters later, Priest and Bishop use public transportation since the Diaconal funds do not run to a taxi; the Bishop lives in a modest demi-detached house, though for courtesy it is dubbed "The Bishop's Palace".

Father Smith is not intimidated by either prejudice or poverty – remarking that suffering a bit of persecution can help to strengthen one's faith, and that the poverty of the Scottish Catholic Church places it closer to the situation of Primitive Christianity. When hit on his head by a jagged stone thrown by bigots, and needing weeks of hospitalization, he considers that the incident can be useful in generating sympathy for the Catholics among the town's mainstream Protestants. And when listening to the singing of his community's amateur chorus, he reflects that no one can doubt the sincerity of their faith – which cannot be said with certainty of the highly-paid tenors singing at the Cathedrals of Seville and Milan.

The most obvious symbol of the Catholic Church's situation is that at the start of the book's plot, the town's Catholics have no church building of their own at all, and must rent the town's vegetable market in which to hold their Sunday prayers. Father Smith makes enormous efforts to rectify this situation, succeeding with great effort to erect a "Tin Church" and finally, after more than two decades of effort, actually having a real Stone Church built. And then, two days before it was to be dedicated, this beautiful new building is destroyed in a WWII German bombing, which also costs Father Smith's life. With literally his last breath, Father Smith reminds the Polish priest who would temporarily replace him that next Sunday's service must be, once again, held in the vegetable market.

A major element of the plot is the arrival of French nuns, driven out of their country by the anti-clericalism of the Third French Republic and who are welcomed in the Scottish town. Father Smith has a strong and affectionate friendship with the French Mother Superior, though of course with no hint of anything which would be improper between a priest and a mother superior. The nuns, bitter with their treatment by the French Government, fly the pre-1789 flag of the House of Bourbon – but at the shocking news of the Fall of France in 1940, both the priest and mother superior raise the French Republican Tricolor at half-mast.

Another major theme are two babies, a boy and a girl, who were born on the same day and baptized together by Father Smith. The grow up in each other's company and as teenagers fall in love – but the boy exhibits a strong religious vocation and enters the priesthood at a young age, foreclosing any chance of their love being consummated. The heart-broken girl goes to Hollywood and become a major film star. She remembers her origins and sends very generous donations to Father Smith's church. He, however, prefers not to see any of her films, fearing to see her in situations which he would find compromising. The boy, who is in effect Father Smith's "spiritual son" develops into a charismatic preacher, drawing large crowds. He is appointed Bishop at an exceptional young age. It is noted that this Scottish Episcopal see is very large, including many far-flung communities, the Bishop needing to do constant traveling – and therefore, better that a young and vigorous man have the job.