Zoological Garden, Alipore

| Zoological Garden, Alipore | |

|---|---|

Official logo of the zoo | |

A white tiger in Alipur zoo Kolkata | |

| |

| 22°32′09″N 88°19′55″E / 22.535913°N 88.332053°E | |

| Date opened | 24 September 1875[1] |

| Location | No. 2, Alipore Road, Alipore, Kolkata-27, West Bengal, India |

| Land area | 18.81 ha (46.5 acres)[2] |

| No. of animals | 1266 |

| No. of species | 108 |

| Annual visitors | 3 million |

| Memberships | CZA,[1] WBZA |

| Website | Official website

eticketaliporezoo |

| |

The Zoological Garden, Alipore (also informally called the Alipore Zoo or Kolkata Zoo) is India's oldest formally stated zoological park (as opposed to royal and British menageries) and a big tourist attraction in Kolkata, West Bengal. It has been open as a zoo since 1876, and covers 18.811 ha (46.48 acres). It is probably best known as the home of the Aldabra giant tortoise Adwaita, who was reputed to have been over 250 years old when he died in 2006. It is also home to one of the few captive breeding projects involving the Manipur brow-antlered deer. One of the most popular tourist attractions in Kolkata, it draws huge crowds during the winter season, especially during December and January. The highest attendance till date was on January 1, 2018 with 110,000 visitors.

History

[edit]

To those who can remember the dirty and rather dismal looking approach to Belvedere, the improved and satisfactory condition of the neighbourhood, at present, must afford a very striking contrast. Both east and west of the roadway leading from the Zeerut bridge were untidy, crowded unsavoury bustees. Today we shall find on the site of the old bustees the Calcutta 'Zoo.' A very large share of the credit for the establishment of this pleasant resort is due to Sir Richard Temple, who was Lieutenant Governor of Bengal from 1874 to 1877, but long before the scheme assumed any proper shape, Dr. Fayrer, C.S.I., in 1867 and again in 1873 Mr. L. Schwendler (known as the 'Father of the Zoo') had brought forward and strongly urged the necessity of a Zoological Garden…The visit to Calcutta of His Majesty King Edward the Seventh, then Prince of Wales, was seized upon as an auspicious occasion. On 1 January 1876, the gardens were inaugurated by His Royal Highness, and in May of the same year they were opened to the public.[3]

The zoo had its roots in a private menagerie established by Governor General of India, Richard Wellesley, established around 1800 in his summer home at Barrackpore near Kolkata, as part of the Indian Natural History Project.[4][5] The first superintendent of the menagerie was the famous Scottish physician zoologist Francis Buchanan-Hamilton. Buchanan-Hamilton returned to England with Wellesley in 1805 following the Governor-General's recall by the Court of Directors in London. The collection from this era are documented by watercolours by Charles D'Oyly, and a visit by the famous French botanist Victor Jacquemont.[6] Sir Stamford Raffles visited the menagerie in 1810, encountering his first tapir there, and doubtless used some aspects of the menagerie as an inspiration for the London Zoo.[4] The menagerie was photographed by John Edward Saché in 1860s. [7]

The foundation of zoos in major cities around the world caused a growing thought among the British community in Kolkata that the menagerie should be upgraded to a formal zoological garden. Credence to such arguments was lent by an article in the now-defunct Calcutta Journal of Natural History's July 1841 issue. In 1873, the Lieutenant-Governor Sir Richard Temple formally proposed the formation of a zoo in Kolkata, and the Government finally allotted land for the zoo based on to the joint petition of the Asiatic Society and Agri-Horticultural Society.

The zoo was formally opened in Alipore - a posh Kolkata suburb, and inaugurated on 1 January 1876 by Edward VII, then Prince of Wales. (Some reports place the inauguration on an alternate date of 27 December 1875).[8] The initial stock consisted of the private menagerie of Carl Louis Schwendler (1838 – 1882), a German electrician who was posted in India for a feasibility study of electrically lighting Indian Railways stations. Gifts were also accepted from the general public. The initial collection consisted of the following animals: African buffalo, Zanzibar ram, domestic sheep, four-horned sheep, hybrid Kashmiri goat, Indian antelope, Indian gazelle, sambar deer, spotted deer and hog deer.

It is not clear whether the Aldabra giant tortoise Adwaita was among the opening stock of animals. The animals at Barrackpore Park were added to the collection over the first few months of 1886, significantly increasing its size. The zoo was thrown open to the public on 6 May 1876.[8]

It grew based on gifts from British and Indian nobility - like Raja Suryakanta Acharya of Mymensingh in whose honour the open air tiger enclosure is named the Mymensingh Enclosure. Other contributors who donated part or all of their private menagerie to the Alipore Zoo included the Maharaja of Mysore Krishna Raja Wadiyar IV.[9]

The park was initially run by an honorary managing committee which included Schwendler and the famous botanist George King. The first Indian superintendent of the zoo was Ram Brahma Sanyal, who did much to improve the standing of the Alipore Zoo and achieved good captive breeding success in an era when such initiatives were rarely heard of.[6] One such success story of the zoo was a live birth of the rare Sumatran rhinoceros in 1889. The next pregnancy in captivity occurred at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1997, but ended with a miscarriage.[10] Cincinnati Zoo finally recorded a live birth in 2001. Alipore Zoo was a pioneer among zoos in the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century under Sanyal, who published the first handbook on captive animal keeping.[11][12] The zoo had an unusually high scientific standard for its time, and the record of the parasite genus Cladotaenia (Cohn, 1901) is based upon cestodes (flatworms) found in an Australian bird that died at the zoo.[13]

Kalākaua, the last king of Hawaii, visited the zoo on 28 May 1881 during his world tour.[14]

Controversy

[edit]Pressed for space as Kolkata developed, and lacking adequate government funding, the zoo attracted a lot of controversy in the latter half of the 20th century due to cramped living conditions of the animals, lack of initiative at breeding rare species, and for cross-breeding experiments between species.

The zoo has also, in the past, attracted a lot of criticism for keeping single and unpaired specimens of rare species like the banteng, great Indian one-horned rhinoceros, crowned crane and the lion-tailed macaque.[15] Lack of breeding and exchange programs has led to the elimination of individuals and populations of environmentally vulnerable species like the southern cassowary, wild yak, giant eland, slow loris and echidna.

The previously cramped, unsuitable and unhygienic conditions inside the cages, and in the zoo in general had been criticized for long. The death of a great Indian one-horned rhinoceros sparked off speculation about the veterinary efficiency at the zoo.[16] ZooCheck Canada found conditions in the zoo unsatisfactory in 2004.[17] The zoo director Subir Choudhury has gone on record in 2006 saying:

We are aware that the animals and birds are not well in the cages and moats. Efforts are on minimizing their agony.[17]

The zoo had also been criticized for the quality of its animal/visitor interaction. Teasing of animals was a common occurrence at the zoo,[18] though corrective measures are now in place. On 1 January 1996 the tiger Shiva mauled two visitors as they tried to garland it, killing one,[19][20][21] Shiva was later shot and killed by the Indian Army. Another mauling leading to a death occurred in 2000. The zoo has also been criticized for its animal/keeper relations. A chimpanzee attacked and severely injured its keeper in Alipore Zoo, and numerous other incidents have been reported including the case of an elephant trampling its mahout to death in 1963 which was subsequently put down.[22] In 2001, it was revealed that zoo staff drugged the great Indian one-horned rhinoceros into relieving itself more often than normal, which enabled them to collect the urine and sell it on the black market as an anti-impotence medicine.[23]

Panthera hybrid program

[edit]The zoo attracted flak from the scientific community in general, because of cross breeding experiments between lions and tigers to produce strains like tigons, and litigons (see Panthera hybrid).

The zoo bred two tigons in the 1970s – Rudrani (b. 1971) and Ranjini (b. 1973) were bred from the cross between a royal Bengal tiger and an African lion. Rudrani went on to produce 7 offspring by mating with an Asiatic lion, producing "litigon"s. One of these litigons, named Cubanacan survived to adulthood, stood over 5.5 feet (1.7 m) tall, measured over 11.5 feet (3.5 m) and weighed over 800 pounds (360 kg). It died in 1991 at the age of 15. It was marketed by the zoo as the world's largest living big cat. All such hybrid males were sterile. Quite a few of these creatures suffered from genetic abnormalities and many died prematurely.

Rangini, the last tigon in the zoo, died in 1999 as the oldest known tigon.[24] The zoo has stopped breeding hybrids after the 1985 legislation passed by the Government of India banning breeding of panthera hybrids after a vigorous campaign by the World Wide Fund for Nature (then World Wildlife Fund).

Attractions

[edit]

The zoo remains one of the most popular winter tourist attractions in Kolkata. The footfall figures in 2016 showed an annual visitation of almost 3 million — more than any other tourist attraction in Kolkata, and a peak of over 81,000 on Christmas Day and New Year's Day.[26]

The zoo displays a large number of crowd-pulling megafauna, including the royal Bengal tiger, Asiatic lion, jaguar, hippopotamus, greater one-horned rhinoceros, giraffe,[27] zebra, and Indian elephant. Previously, other megafauna like the Panthera hybrids and the giant eland were present.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the zoo live streamed virtual tours on Facebook.[28]

The zoo has chosen to upgrade customary checking of large felines and exacting execution of security standards after a tiger tested positive for COVID-19 at a zoological gargen in New York, an authority said on Monday. Since mid-February a few prudent steps, for example, spraying of antiviral medication inside the enormous felines' fenced in area and in the nursery have been taken.[29]

The zoo sports a large collection of attractive birds, including some threatened species - large parrots including a number of parrots, lories and lorikeets; other birds like hornbills; colourful game birds like pheasants and some large flightless birds like the emu and ostrich.

Layout

[edit]Laid out on 45 acres (18 ha) of land, the Calcutta zoo has been unable to expand or modify its layout for over 50 years, and thus has a rather backdated plan. It contains a Reptile House (a new one has been built), a Primate House, an Elephant House, and a Panther House which opens out onto the open air enclosures for the lions and tigers. It also boasts of a glass-walled enclosure for tigers, the first of its kind in India. A separate Children's zoo is present, and the central water bodies inside the zoo grounds attracts migratory birds.

The Calcutta Aquarium lies across the street from the zoo, and is affiliated to the zoo.

Adwaita

[edit]The most famous specimen in the zoo was probably the Aldabra giant tortoise "Adwaita", gift when it died in 2006 – a contender for the longest lived animal.[30]

Animals

[edit]The zoo has around 1,266 individuals and about 108 species.[31][32][33]

Breeding programs

[edit]The zoo was among the first zoos in the world to breed white tigers and the common reticulated giraffe. While it has successfully bred some megafauna, its rate of breeding rare species had not been very successful, often due to lack of initiative and funding. One notable exception is the breeding programme of the Manipur brow-antlered deer, or thamin which has been brought back from the brink of extinction by the breeding program at the Alipore Zoo.[6]

Adoption scheme

[edit]An "Adopt an Animal" scheme began at the Alipore Zoological Gardens in August 2013 as a way to obtain funding for the zoo. About 40 animals were adopted as of August 2013[35] The adopters receive tax benefits, are allowed to use photos of the animals in promotional materials, and get their name placed on a plaque at the animal's enclosure. Sanjay Budhia, chairman of Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) national committee on exports, adopted a one-horned rhino. Ambuja Group chairman Harsh Neotia and Narayana Murthy of Infosys have requested to adopt animals.[36]

Reforms

[edit]The zoo is presently downsizing to meet animal comfort requirements laid down by the Central Zoo Authority of India (CZAI).[37] It has also increased the number of open air enclosures.[38] A move to a suburban location was also contemplated, but was not undertaken based on the recommendations of the CZAI, which claimed the Alipore site was of historical significance. The CZAI also cleared the zoo of malpractices in an evaluation performed in late 2005,[39] even though the zoo has continued to attract bad press.

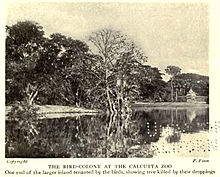

Ecological significance of the zoo grounds

[edit]The zoo is also home for wintering migratory birds such as ducks, and sports a sizable wetland inside the zoo grounds. Since the zoo is enveloped by urban settlements for miles, the zoo wetlands are the only resting spot for some of the birds and are a focus of conservationists in Kolkata. However, the number of migratory bird visiting the zoo dropped from documented highs by over 40% in the winter of 2004–2005. Experts attribute the causes of the decline to increased pollution, new construction of highrises in the area, increasing threats in the summer grounds of the birds[40] and declining quality of the water bodies at the zoo.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Annual Reports of Zoo - Alipore Zoological Garden - 2019-20" (PDF). www.cza.nic.in. Central Zoo Authority of India.

- ^ "Area Distribution". kolkatazoo.in. Kolkata Zoo. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Cotton, H.E.A., Calcutta Old and New, 1909/1980, pp783-784, General Printers and Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- ^ a b Sally R. Walker; The Indian Natural History Project (1801-1808) and the Menagerie at Barrackpore (1803-1878) ;Lost, stolen or strayed: the fate of missing natural history collections; Naturalis Museum, Leiden, The Netherlands. 10–11 May 2001

- ^ Sally R. Walker; Descriptions and Drawings of Selected Quadrupeds of the Indian Natural History Project, Barrackpore ;Lost, stolen or strayed: the fate of missing natural history collections; Naturalis Museum, Leiden, The Netherlands. 10–11 May 2001

- ^ a b c Gautaman Bhaskaran, Where past overshadows present[usurped], The Hindu, 14 January 2001

- ^ "The Menagerie - Barrackpore - John Edward Saché". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ a b D. K. Mittra, Role of Ram Brahma Sanyal in initiating zoological researches on the animals in captivity[permanent dead link], Indian Journal of History of Science, 27(3), 1992

- ^ .html Article, The Wellsboro Gazette, 1 May 1919

- ^ Rhino loses fetus, Cincinnati Post, 14 November 1997

- ^ Walker, S.: Ram Brahma Sanyal – the first zoo biologist. Zoos' Print Journal Vol. 15, No. 5 (1999), Back when . . . & then? section, p. 9.

- ^ Kisling, V.N.: Zoo history and the Sanyal legacy. Zoos' Print Journal Vol. 14, No. 4 (1999), Back when . . . & then? section, p. 2

- ^ Website[permanent dead link] of the Government of Australia

- ^ "Ellora Caves". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Somdatta Basu, Endangered singles bug matchmakers, Times of India, 10 August 2005 [dead link]

- ^ Madhumita Mookerji, Of beasts, men and the Central Zoo Authority, Daily News and Analysis, 12 November 2005

- ^ a b In Indian zoos, life can be brutal and short Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Lanka Business Online, 5 June 2006

- ^ Staff reporter, Parched & pained: it's a dog's life at Alipore zoo, Times of India, 9 June 2003

- ^ Richard Leiby, Lions and tigers and beers, Washington Post, 7 January 1996

- ^ "geocities". Archived from the original on 18 January 2000.

- ^ big cats

- ^ Article, The Gleaner, Kingston, Jamaica, 22 August 1963

- ^ Horn of plenty, Daily Mirror, 22 October 2001

- ^ Kathy Moran, Dad's a lion, mum's a tiger, Sunday Mirror, 29 August 1999

- ^ Finn, Frank, (1907) Ornithological and other oddities. John Lane, The Bodley Head. London.

- ^ City Lights, The Telegraph, Kolkata, 1 February 2003

- ^ Tripathy, Pritimaya (21 August 2019). "Thane-based conservationist tracks genetics of giraffes". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Darjeeling, Kolkata zoos to host virtual tour to live stream its animals". Hindustan Times. 16 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Patrick R. (2000). <283::aid-zoo6>3.0.co;2-8 "Tiger conservation in the new millennium". Zoo Biology. 19 (4): 283–285. doi:10.1002/1098-2361(2000)19:4<283::aid-zoo6>3.0.co;2-8. ISSN 0733-3188.

- ^ UNI, 255 year old giant tortoise Adwaita dead Archived 8 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Deccan Herald, 24 March 2006

- ^ "Mammals". kolkatazoo.in.

- ^ "Reptiles". kolkatazoo.in.

- ^ "Birds". kolkatazoo.in.

- ^ "Famous 'man-eater' at Calcutta". Underwood & Underwood. 1903. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Roy, Shobha (18 August 2013). "Under foster care". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ "Narayana Murthy to adopt animal at Kolkata zoo". 2 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ Staff reporter, Fewer animals, more space in Alipore Zoo, 21 November 2004

- ^ Q&A, Open enclosures in new wing, The Telegraph, 2 January 2006

- ^ Jayanta Basu, Improved conditions in menagerie, The Telegraph, 15 November 2005

- ^ Staff reporter, Bird headcount kicks off, The Telegraph, 9 January 2005

- ^ Suchetana Haldar, Where have all the birds gone?, Kolkata Newsline, 3 January 2006

Notes

[edit]- 125 years of Calcutta Zoo, The Managing Committee, Zoological Gardens, Alipore, Calcutta, (2000)

- Walker, S; A Big Year for Alipore Zoological Garden April (2000)

- Mitra, D.K.; The history of Zoological Gardens, Calcutta; Zoos' Print Journal Vol. 15, No. 5 (1999)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Photographs of the zoo