Alexios Komnenos (protosebastos)

Alexios Komnenos | |

|---|---|

The blinding of Alexios Komnenos, illuminated miniature from a manuscript of the history of William of Tyre, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France | |

| Born | c. 1135 or 1142 Constantinople |

| Died | after 1182 Constantinople |

| Noble family | Komnenos |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Doukaina |

| Father | Andronikos Komnenos |

| Mother | Irene |

Alexios Komnenos (Greek: Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός; ca. 1135/42 – after 1182) was a Byzantine aristocrat and courtier. A son of Andronikos Komnenos (son of John II) and nephew of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, he rose to the high ranks of prōtostratōr, prōtosebastos and prōtovestiarios during Manuel's reign. Following Manuel's death in 1180, he won the favour, and likely became the lover, of Empress-dowager Maria of Antioch and through her ruled the Empire until he was overthrown by Andronikos I Komnenos in 1182.

Origin and early career under Manuel I

Alexios was the second son and the last of five children of the sebastokratōr Andronikos Komnenos, second son of Emperor John II Komnenos, and his wife Irene.[1] His birth was celebrated by the poet Theodore Prodromos, who composed a laudatory poem on the occasion.[2] The Greek scholar Konstantinos Varzos, in his prosopographical study of the Komnenoi, placed his birth on Easter Day 1135 (or possibly 1134 or 1136) as he was old enough to participate in a campaign in 1149/50.[3] His father died in August 1142, while on campaign with his father and brothers in southern Asia Minor. Andronikos died only a little while after his elder brother Alexios, and probably of the same illness.[4] This provided the occasion for another poem by Prodromos, who claims that the young Alexios was the only solace for his devastated mother.[5][6] The Prosopography of the Byzantine World database on the other hand interprets the poems as indicating that Alexios was born in 1142, during his father's absence on campaign.[6]

When John II died in 1143, his two remaining sons were Isaac and the younger Manuel, who eventually, due to the support of the army, became emperor. Isaac, despite his protests, never actively threatened Manuel's rule, however.[7] Although Alexios' mother, the sebastokratorissa Irene, suffered repeated disgrace and imprisonment at the hands of Manuel, the emperor showed great favour to her sons, particularly Alexios' older brother John.[8] In ca. 1149/50, like all young Byzantine aristocrats, the young Alexios was required to begin his military training and accompany his uncle, Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, on campaign. No details are known of his early military career, however.[9] In ca. 1153/4 he married Maria Doukaina, whose exact parentage is unknown. Together they had at least four children: a son Andronikos, a daughter Irene, and a son and daughter whose names are unknown.[10]

The first record of Alexios in a public function was at a synod at the imperial Palace of Blachernae, along with his brother John, on 12 May 1157. He also participated along with John in the synod of March 1166. In both cases, Alexios is recorded without any rank or title, among the imperial relatives.[11] In May/June 1167, following the dismissal and banishment of the hitherto holder, Alexios Axouch, Alexios Komnenos assumed the high office of prōtostratōr. He appears with this rank in the synod of February 1170 against John Eirenikos.[12] Sometime during the period where he held the office of prōtostratōr, i.e. 1167–76, Alexios fell gravely ill, and his wife donated a richly embroidered veil to the Church of the Saviour at the Chalke Gate, an occasion celebrated by an anonymous court poet.[13]

Like most of the Byzantine aristocracy, Alexios took part in the campaign that led to the disastrous Battle of Myriokephalon in September 1176. His brother John was one of the casualties of the battle, and Alexios, as the last remaining son of Manuel's brothers, succeeded him in his titles of prōtosebastos and prōtovestiarios.[14] These titles raised Alexios, like John before him, to the pinnacle of the Byzantine court: as prōtosebastos, he was the most senior of the sebastoi—a group which since the days of Alexios I Komnenos denoted the most senior members of the court, usually close relatives or special favourites of the emperor[15] —and as prōtovestiarios, he was the "titular head of the imperial household" (Paul Magdalino), with important ceremonial and diplomatic duties.[8] His previous post of prōtostratōr went to another Alexios, son of Andronikos Komnenos Vatatzes.[16] Soon after Alexios' promotion, his wife died, and his son Andronikos was mortally injured after falling from his horse. The poet Gregory Antiochos wrote a lament on the occasion.[17]

In spring 1178, Alexios led an embassy to France. His first mission concerned the marriage of his cousin Eudokia—daughter of his paternal uncle Isaac—to Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Provence, brother of King Alfonso II of Aragon. The marriage was aborted due to the opposition of the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa, however, and Eudokia was married instead to William VIII of Montpellier. He then proceeded to Paris, to escort Agnes, a daughter of King Louis VII of France and the prospective bride of Manuel's son and heir Alexios II Komnenos, back to Byzantium. The embassy left Paris on Easter 1179, and returned via Italy to Constantinople, where Agnes and Alexios II were betrothed.[18]

Rise to power

When Manuel died on 24 September 1180, his successor, Alexios II, born in 1169, was underage. Manuel had neglected providing for a regency, and power automatically passed to the hands of his widow, Maria of Antioch. Although she had become a nun, the Empress-dowager immediately became the focus of attention of ambitious suitors who sought to win her affection and supreme power along with it.[19] Alexios quickly emerged as the winner in this competition for the Empress-dowager's favour, and alongside Maria became the de facto regent of the state.[20] At the time, rumours that he also became Maria's lover, but although this was certainly widely believed at the time, modern scholars like the biographer of the Komnenoi, Konstantinos Varzos, consider it open to doubt; while the contemporary official and historian Niketas Choniates reports the rumour almost as fact, the 13th-century chronicler Theodore Skoutariotes appears to have considered these rumours baseless.[21] Nevertheless, Alexios evidently exercised considerable power. As Choniates writes, "confident of his own power and his great influence over the empress", Alexios "had the emperor promulgate a decree that henceforth no document signed by the imperial hand would be valid unless first reviewed by Alexios and validated by his notation "approved" (ἐτηρήθησαν) in frog green ink", so that "nothing whatsoever could be done except through him". In addition, all revenue was channeled directly to the prōtosebastos and the Empress-dowager.[22][23][24] Soon rumours began to circulate that the prōtosebastos planned to supplant the young emperor and "mount both the mother and the throne", as Choniates put it.[25]

Whether Alexios intended to usurp the throne or not, his concentration of power alarmed the other imperial relatives, above all Emperor Manuel's daughter from his first marriage, the porphyrogennētē princess Maria Komnene, whose relations with her step-mother were already strained before Manuel's death, and who according to Choniates was incensed at the thought of the prōtosebastos and the Empress-dowager sullying her father's bed. The opposition that began to coalesce around her included her husband, the Caesar Renier of Montferrat, Manuel's illegitimate son the sebastokratōr Alexios Komnenos, the prōtostratōr Alexios Komnenos, the Eparch of the City John Kamateros, Andronikos Lapardas, Maria's cousins Manuel and John, sons of the future emperor Andronikos I Komnenos (who was then in exile), and many others. These leading aristocrats were driven by their exclusion from the share in power and wealth they had enjoyed under Manuel, and the fear that they themselves might be imprisoned.[26][27][28] Choniates, the contemporary archbishop Eustathius of Thessalonica, and William of Tyre report that, finding themselves ever more unpopular, the Empress-dowager and Alexios turned to the numerous Latin residents of Constantinople and Latin mercenaries for support, continuing and even augmenting Manuel's pro-Latin policies.[23][29] Although some modern historians, like Charles Brand, have therefore viewed the contest between the prōtosebastos and the faction around Maria as that of pro-Latin and anti-Latin parties,[30] most modern historians stress that lines were not so clear cut, as the opposing aristocrats included Latins like Renier and also recruited Latin mercenaries, and that the primary concern of the opposition was the prōtosebastos domination of government, which had destroyed Manuel's arrangements where they had been "equal in power".[25][28]

Revolt of Maria Komnene

According to Choniates, the conspirators planned to assassinate Alexios when he and the emperor were to visit the suburb of Bathys Ryax for the feast day of the martyr Theodore, "on the seventh day of the first week of Lent". The conspiracy was betrayed, however, by a soldier, and most of its members were arrested, tried by a tribunal under the dikaiodotēs Theodore Pantechnes—who succeeded Kamateros as Eparch—and imprisoned in the dungeons of the Great Palace. Andronikos Lapardas managed to escape, while the Caesarissa Maria and her husband sought refuge in the Hagia Sophia, where she soon gained the support not only of the Patriarch Theodosios Borradiotes, but also of the common people, who took pity on her plight and her imperial descent, and who were further won over due to her largesse in distributing coins to the crowd.[31][32] Emboldened by the popular support, the princess refused Alexios' offers of an amnesty, demanding not only the repetition of the trial of her co-conspirators, but also the immediate dismissal of the prōtosebastos from the palace and the administration. When the Empress-dowager and the prōtosebastos had Alexios II issue a warning to his half-sister that she would be evicted by force, she again refused, and despite the Patriarch's angry objections started posting her followers to keep watch over the entrances to the great church, recruiting even "Italians in heavy armor and stouthearted Iberians from the East who had come to the City for commercial purposes", as Choniates reports. To them were added the masses of the capital's people, who assembled and began publicly to sympathize with Maria and denounce the prōtosebastos and the Empress-dowager. Led by three priests, the populace was driven to rebellion, and over several days they not only demonstrated before the gates of the palace, but also ransacked several mansions of the nobility, including that of Pantechnes.[33][34]

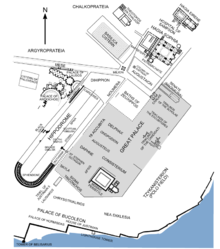

Matters finally came to a head on the seventh day of the uprising, as the prōtosebastos brought in troops from both Asia and Europe, under the command of Sabbatios the Armenian. Princess Maria's supporters in the meantime barricaded themselves behind the Augoustaion square between the Great Palace and the Hagia Sophia, after they razed the adjoining buildings. Moving forward at dawn, the imperial troops ascended the roof of the Church of St. John the Theologian, and then moved to cut off the Hagia Sophia and Maria's supporters in the Augoustaion from the rest of the city. After a fiercely contested battle, towards evening Maria and her followers were driven from the arches at the entrance of the Augoustaion and their positions on top of the Milion and the Church of Alexios (on the western side of the square, north of the Milion) into the open square. Protected by their fellows who fired missiles from the upper galleries of the Hagia Sophia, the rebels began to withdraw into the exonarthex of the Hagia Sophia, while the imperials were reluctant to follow "in fear of the temple's narrow passageways". At this point, the Caesar Renier, rallied about 150 of his men from his own Latin bodyguards and his wife's servants and followers, gave a speech justifying their struggle, and led them forth against the imperial troops in the Augoustaion, who retreated hastily and in confusion. As Choniates writes, "the imperial troops no longer dared to enter the open court but preferred to fight by firing missiles". Renier returned to the Hagia Sophia, and with the fall of night, a stalemate ensued.[35][36] At this juncture, the Patriarch interceded with Empress Maria of Antioch to put an end to the fighting. In response, a delegation of the most distinguished nobles and officials, led by the megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos and the megas hetaireiarchēs John Doukas were sent to the Caesarissa and Renier in the Hagia Sophia. There they "gave her pledges of good faith confirmed by oaths, assuring her that nothing unpleasant would befall her. She would not be deprived of her dignities and privileges by her brother the emperor, or her stepmother the empress, or the prōtosebastos Alexios, and full amnesty would be granted her supporters and allies". With this, the two sides disbanded their forces, and Maria and her husband returned to the Great Palace to meet the Empress-dowager and the prōtosebastos and confirm their reconciliation.[37][38]

The dating of these events is disputed. Choniates records the date of the clash between the supporters of the Caesarissa and the imperial troops as 2 May on the 15th indiction, i.e. 2 May 1182, but as Varzos points out, this is clearly an error, as this was the date of the Massacre of the Latins. Many modern scholars have therefore interpreted the date as 2 May 1181,[39] but this contradicts the indiction dating given by Choniates.[40] Among the scholars who accept the dating of these events to 1181, several, including the English translator of Choniates, Harry Magoulias, place the date of the intended coup on 7 February, but as Choniates' German editor Jean-Louis Van Dieten points out, the correct date for the feast described by Choniates is 21 February for the year 1181.[41] According to this chronology, the condemnation of the conspirators took place on 1 March, and the clashes took place on 2 May.[42][43] The historian Oktawiusz Jurewicz, in his study on Andronikos I Komnenos, placed the events in 1182. As other events took place soon after, he proposed that the uprising and reconciliation all took place in February 1182, with the date for the original, aborted coup on 13 February.[40]

References

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 189, 192.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 189–191.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, p. 189.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, pp. 359–361.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b "Alexios 25003". Prosopography of the Byzantine World. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Magdalino 2002, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Magdalino 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, p. 193.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, p. 195.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Magdalino 2002, p. 181.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, p. 198.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 194 (note 20), 198.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, p. 201.

- ^ Magoulias 1984, p. 130.

- ^ a b Varzos 1984b, p. 202.

- ^ Simpson 2013, p. 200.

- ^ a b Varzos 1984b, p. 203.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 202–204.

- ^ Simpson 2013, pp. 200–201.

- ^ a b Magdalino 2002, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 33.

- ^ Brand 1968, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Magoulias 1984, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Magoulias 1984, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 207–211.

- ^ Magoulias 1984, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Magoulias 1984, pp. 135–136.

- ^ cf. Simpson 2013, p. 304, Van Dieten 1999, pp. 102ff.

- ^ a b Varzos 1984b, p. 208 (note 92).

- ^ Van Dieten 1999, p. 102 (note 4).

- ^ Van Dieten 1999, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Simpson 2013, p. 304.

Sources

- Brand, Charles M. (1968). Byzantium confronts the West, 1180–1204. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. LCCN 67-20872.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Magdalino, Paul (2002) [1993]. The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52653-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Magoulias, Harry J., ed. (1984). O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniatēs. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simpson, Alicia (2013). Niketas Choniates: A Historiographical Study. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967071-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van Dieten, Jean-Louis (1999). "Eustathios von Thessalonike und Niketas Choniates über das Geschehen im Jahre nach dem Tod Manuels I. Komnenos". Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik (in German). 49: 101–112. ISSN 0378-8660.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Varzos, Konstantinos (1984a). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών (PDF) (in Greek). Vol. A. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Varzos, Konstantinos (1984b). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών (PDF) (in Greek). Vol. B. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)